Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 1997 Nickeleit 1832 8

Загружено:

Abdul Muin RitongaИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 1997 Nickeleit 1832 8

Загружено:

Abdul Muin RitongaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Nephrol Dial Transplant ( 1997) 12: 18321838

Nephrology

Dialysis

Transplantation

Personal Opinion

Uric acid nephropathy and end-stage renal disease

Review of a non-disease

V. Nickeleit and M. J. Mihatsch

Institute of Pathology, University of Basel, Kantonsspital, Basel, Switzerland

Key words: gout; nephropathy; renal insuciency;

Morphology

tophus

Morphological changes seen with the precipitation of

uric acid crystals in the kidney can be divided into two

major groups: (1) chronic (=gouty nephropathy with

tophi), and (2) acute. Typically, precipitated crystals

Introduction

(mainly monosodium urate and less often ammonium

urate [6]) are found in the medulla; (collecting ducts

Traditionally, patients suering from gout were

show the highest uric acid concentration of the body

thought to be at high risk for renal complications

[7]).

[1,2], in particular the formation of uric acid calculi

in the renal pelvis and so-called gouty nephropathy

Chronic hyperuricaemic nephropathy (Figures 14)

with tophus formation. Mainly the latter complication

will be discussed here.

This is the classic gout kidney with formation of

The precipitation of uric acid in the renal medulla

tophi at the cortico-medullary junction and deep in

with formation of characteristic tophi was believed to

the medulla. Chronic hyperuricaemia can lead to pre-

evoke an inammatory response leading to brosis, a

cipitation of uric acid crystals mainly in distal collecting

loss of nephrons, and ultimately to chronic irreversible

ducts and the interstitium (tophus formation). The

renal failure. Some reports emphasize that nearly 100%

exact pathophysiological mechanism is not entirely

of patients with chronic gout also have some renal

clear since hyperuricosuria and therefore simple oversa-

involvement [1,2]. Most dramatically, it has been

turation of the urine is not a prerequisite (compare

stressed by some that renal failure can occur in a high

with the acute type) [8]. Quite commonly a decrease

percentage of patients (up to 41%) with chronic gout

in renal function (decrease in glomerular ltration,

[2,3]. Based on a prevalence of gout (that is to say

and/or tubular transport) is an accompanying feature.

symptomatic hyperuricaemia with arthritis) of

The interstitial uric acid crystals probably originate

1.33.7% in the general population [4,5], and the

from ruptured ducts. The crystals evoke a foreign body

assumption that renal tophi cause functional deteriora-

reaction with central accumulation of crystalloid mat-

tion, a signicant number of patients should show

erial (monosodium urate) surrounded by a rim of

gouty nephropathy and renal insuciency. In order to

leukocytes, giant cells and brosis; this histological

determine the frequency of uric acid deposition in the

hallmark is called gout tophus [6,8,9]. In patients with

kidney and to correlate the presence of tophi with data

a long-standing history of gout, kidneys frequently

on renal function in a large autopsy series, we screened

show not only gouty tophi but also brosis, glomerulo-

the autopsy les at the Institute of Pathology, Basel,

sclerosis, arteriolosclerosis and arterial wall thickening

from 1968 to 1976 (n=11 408). Since approximately

caused by intimal brosis [6,9]. However, these latter

45% of all deaths in those years were examined by

histological ndings are non-specic and can be seen

necropsy, data gathered are fairly representative for

in various other renal diseases, such as hypertension

the population in general. In theory (using the gures

or interstitial nephritis.

mentioned above) in our series around 100 patients

(roughly 1%) might be expected to present with gouty

Acute hyperuricaemic nephropathy (Figures 58)

nephropathy and severe renal insuciency.

Acute hyperuricaemic nephropathy is usually not asso-

ciated with gouty arthritis. It is most often ( but not

exclusively) found in children suering from haemato-

Correspondence and oprint requests to: M. J. Mihatsch MD, Inst.

poietic malignancies. Tumour cell necrosis leads to a

of Pathology, Kantonsspital, University of Basel, Schoenbeinstrasse

40, CH- 4003 Basel, Switzerland. brisk increase of purine catabolism, to hyperuricaemia,

1997 European Renal AssociationEuropean Dialysis and Transplant Association

Uric acid nephropathy and end-stage renal disease 1833

Fig. 1. Gouty tophi in joint and kidney. Chalky white urate deposits are visible in the articular cartilage (right). The corresponding kidney

( left) shows yellowish areas in the pyramids (arrow) representing brosis and urate deposits.

Fig. 2. Typical gouty tophus in the renal medulla with crystalloid material in the centre surrounded by a narrow rim of brosis and

inammation. Note: The tophus probably originated from a ruptured collecting duct (arrow). H&E stained section, 50 original

magnication.

and characteristically to hyperuricosuria. Frequently, who were intrigued by the yellow macroscopic appear-

ance resembling infarcts.) also dehydration and a low pH of the urine are

associated clinical ndings. Due to the sudden oversat-

uration of uric acid in the urine, uric acid precipitates

as crystals or sludge in tubules and collecting ducts.

Prevalence of renal uric acid deposits in the Basel

These precipitates cause obstruction and acute renal

series

failure [8]. Interstitial brosis or tophus formation is

generally not encountered. With appropriate treat-

ment, renal function normally recovers, and impair- To determine the overall frequency of urate deposits

in the kidney and to correlate morphological ndings ment is therefore mostly transient [5,8]. Also the

so-called uric acid renal infarct of the newborna with renal function, we evaluated 11 408 consecutive

autopsies performed at the Institute of Pathology in rare, functionally insignicant condition caused by

postnatal lysis of immature red blood cells [6,8] Basel from 1968 to 1976. Only 39 cases (=0.34%)

displayed renal urate deposits, two of which were belongs into this category. ( The name uric infarct

represents a misnomer coined by pioneer pathologists classied as acute hyperuricaemic nephropathy and the

V. Nickeleit and M. J. Mihatsch 1834

Fig. 3. High-power view of a tophus, with central urate deposition surrounded by mononuclear inammatory cells and scattered giant cells

(arrow). H&E stained section, 160 original magnication.

Fig. 4. Gouty tophus in renal medulla ( left; acid fuchsinorange G stain, 125 original magnication). Centre of a tophus with uric acid

crystals (right; polarized light, 140 original magnication).

remaining 37 (=0.32%) as chronic hyperuricaemic nephropathy, diabetes mellitus, glomerulonephritis,

analgesic nephropathy, pyelonephritis etc.). nephropathy.

Further analysis of the data showed that 199 patients From 11 408 patients (=100%) studied by postmor-

tem examination only three (=0.03%) had chronic (from the total pool of 11 408 examined) suered from

chronic irreversible renal failure (excluding all non- hyperuricaemic nephropathy and irreversible renal fail-

ure not due to other underlying conditions. Even in renal and all reversible forms of functional abnormalit-

ies as well as cases of renal malignancies). Although the group of 37 patients with chronic renal urate

deposits, the subgroup of three (=8%) with renal the exact morphological classication of kidneys at

end stage is dicult, in the group of 199 patients (= failure is small.

It is fair to assume that more than 200 patients in 100%) with chronic renal failure only three (=1.5%)

had histological evidence of pure chronic hyperurica- our study had suered from gout. Getting back to the

gures mentioned in the introduction, in theory more emic nephropathy. All of the remaining 196 cases of

insuciency could (better) be explained by other types than 150 might have been expected to show chronic

hyperuricaemic nephropathy and about 100 patients of underlying renal disease (such as hypertensive

Uric acid nephropathy and end-stage renal disease 1835

Figs 5 and 6. Acute hyperuricaemic nephropathy with yellow/white streaks in the pyramids (=intratubular urate deposits without brosis).

Figure 5 shows the kidney of a newborn with so-called uric acid infarcts (arrows).

should have additionally presented with renal representative for the autopsy series or the population

in general ). insuciency.

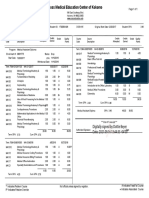

Distribution of urate deposits (Table 1)

Gout and renal disease

Tophi were found either in the kidneys or in the joints

or in both locations simultaneously. Twenty-eight

In an unpublished series, H. U. Zollinger collected a

patients presented with obvious clinical signs of gout;

series of 60 patients with proven clinical and/or mor-

32 did not. In the subgroup of patients with clinical

phological evidence of gout (this case selection is not

gout, 36% presented with renal tophi. Altogether, renal

tophi were found in 37 patients (=62%), among those

Table 1. Distribution of urate deposits (n=60)

13 (=22%) with sole kidney involvement. Interestingly,

these 13 patients did not present with clinical signs

of gout. Clinical symptoms Location of urate deposits

Only joint Joint and kidney Only kidney

Renal tophi and abnormalities of kidney function

(Table 2)

Present (n=28) 18 10 0

Further analysis showed that 28 patients had evidence

Absent (n=32) 5 14 13

of deterioration of renal function; 32 did not. In the

V. Nickeleit and M. J. Mihatsch 1836

Fig. 7. Acute hyperuricaemic nephropathy with intratubular urate deposits in the medulla. Schultz stain for uric acid, 6 original

magnication.

Fig. 8. Urate has precipitated in ducts of the renal medulla. The aected tubules are dilated and epithelial cells are injured. A small segment

of tubular basement membrane seems denuded (arrows). Note. There is no inammatory response in the interstitium. H&E stained section,

125 original magnication.

group of 28 patients with abnormal renal function, 22

(=79%) had renal tophi. However, also in the group

Table 2. Renal tophi and abnormalities of kidney function (n=60)*

of patients with normal renal function, tophi were

noted in 15 (=47%). Statistical analysis (chi-square

Renal function Renal tophi test) showed a correlation between renal tophi and

functional deterioration (P<0.03; renal diseases other

Present Absent

than gout were not specically excluded from this

analysis).

Normal 15 17 (n=32)

Analysing possible causes of deterioration of renal

Deteriorated (n=28) 22 6

function in the group of 22 patients with tophi, in 19

patients pyelonephritis was found, in eight nephrolithi-

*P<0.03, chi-square test; if renal diseases other than gout are

asis, in two hydronephrosis, and in two chronic inter-

excluded from the analysis, the statistical signicance is no longer

found. stitial nephritis. End-stage renal disease was only

Uric acid nephropathy and end-stage renal disease 1837

found in patients with calculi. Thus, all of these 22 patients were untreated was 6 years). After a mean

follow-up of 6.3 years, only a mild increase in serum cases of functional impairment could be (better)

explained by renal diseases other than gout! creatinine (1.70.2 mg/dl ) was noted in 10% of

patients. The author also tried to predict in a mathem-

atical model serum creatinine levels after 40 years of

Summary

continous serum uric acid levels of either 9.3 or

12.9 mg%. He estimated the serum creatinine levels to

Analysis of 11 408 autopsy cases showed that chronic

increase to a modest 1.8 or 2.7 mg% respectively.

hyperuricaemic nephropathy was found in only 37

Berger and Yu [12], in a study of 524 gouty indi-

patients (=0.3%), less frequently than expected. In a

viduals, found in all of their patients abnormalities in

selected group of patients carrying the clinical diagnosis

renal function explainable by other diseases such as

of gout, renal urate depositis were encountered more

hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or pyelonephritis.

often (=36%). The presence of gouty tophi in the

Gouty nephropathy by itself did not seem to cause

kidney was statistically signicantly correlated with

renal failure or even impairment of function over

abnormal renal function (P<0.03). However, this cor-

follow-up periods of up to 12 years. Only renal stones

relation could no longer be established after exclusion

and pyelonephritis had adverse eects on functional

of all cases with other well known causes of renal

parameters.

disease (in our selected group of 22 patients not a

Batuman et al. [13] found a high correlation between

single one remained). In the entire autopsy series of

gout, renal impairment, and increased levels of mobiliz-

11 408 cases, only three patients (=0.03%) showed

able lead. In their study, gouty patients with normal

chronic hyperaluraemic nephropathy and renal failure

lead mobilization did not present with renal impair-

not otherwise explained. Also in the group of patients

ment. In this context it should be mentioned that

presenting with chronic renal insuciency (n=199)

natives in Polynesia were found to have markedly

these three cases (=1.5%) represented a small fraction

elevated serum uric acid levels without progression to

only. The same is true for the whole group of patients

renal failure [14]. Recent publications [4,15] also ques-

with chronic hyperuricaemic nephropathy (n=37), in

tion the rational behind any intervention in cases of

which the three cases accounted for barely 10%. And

asymptomatic hyperuricaemia, setting the therapeutic

even in these three cases the question remains

threshold at 13 mg/dl for men [4]. Finally, whether

unanswered whether possibly the renal insuciency

renal insuciency encountered in patients with the

preceded the deposition of urate. Furthermore, renal

inherited form of familial juvenile gout is denitely

tophi were also detected in a signicant number of

caused by hyperuricaemia, or perhaps by a still

patients lacking any deterioration of renal function

undetermined pathway, remains unknown.

( 47%, n=37).

Interestingly, renal tophi appeared to be more

common in patients not presenting with obvious clin-

Conclusion

ical symptoms of gout. Although urate deposits in the

kidney were found without accompanying deposits in

Based on our investigation of 11 408 autopsy cases and

the joints, this phenomenon was no longer obvious in

the reported data in the literature, we think that

cases with a well-established clinical diagnosis of gout.

chronic uric acid deposits in the kidney (=renal tophi )

hardly ever cause terminal irreversible renal failure.

Deterioration of renal function can nearly always be

Gouty renal tophi and renal failuremyth or

better explained by other well-known risk factors. In

reality?

a signicant number of cases, renal tophi were also

found even without evidence of renal malfunction.

Gouty nephropathy and its eect on renal function in a

Thus, in a patient suering from gout, severe renal

brief review of the literature

damage with pronounced functional alterations is

Using oxonic acid as a dietary supplement, Bluestone almost invariably due to other diseases such as arterial

et al. [10] succeeded in a long-term rat model to hypertension, diabetes mellitus, nephrolithiasis, and

produce hyperuricaemia and hyperuricosuria. After 52 pyelonephritis. Whether renal tophi in association with

weeks renal tophi were found in only few animals an underlying kidney disease lead to a more rapid

( 10%), whereas surprisingly early on after only 4 deterioration of renal function remains undetermined.

weeks, ~66% of animals had tophus formation. After However, from a practical point of view, gout tophi

1 year morphological alterations in the kidneys were in the renal parenchyma do not seem to be of great

minimal and limited to mild interstitial brosis. Neither signicance for patient management.

glomerular nor vascular abnormalities were noted.

Over the entire observation period of 52 weeks, renal

References

function remained normal. The only major complica-

tion were renal stones, found in 75% of animals.

1. Gudzent F. Gicht und Rheumatismus. Springer Verlag, Berlin,

Fessel [11] studied a group of 72 patients with

1928

hyperuricaemia and clinical symptoms of gout, who

2. Talbot JH, Terplan KL. The kidney in gout. Medicine

(Baltimore) 1960; 39: 405467 did not receive any treatment (mean time that the

V. Nickeleit and M. J. Mihatsch 1838

3. Barlow KA, Berlin LJ. Renal disease in primary gout. Q J Med 9. Heptinstall RH. Tubular disorders and various metabolic dis-

1968; 37: 7996 eases. In: Heptinstall RH (ed.) Pathology of the Kidney, 4th edn.

4. Becker MA, Roessler BJ. Hyperuricemia and gout. In: Scriver

Vol. III. Little, Brown, Boston, 1992; 19892043

CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D (eds.). The Metabolic and

10. Bluestone R, Waisman J, Klinenberg JR. Chronic experimental

Molecular Basis of Inherited Disease. McGraw-Hill Inc, New

hyperuricemic nephropathybiochemical and morphologic

York, 1995; 16551677

characterization. Lab Invest 1975; 33 ( 3): 273279

5. Wortmann RL. Gout and other disorders of purine metabolism.

11. Fessel WJ. Renal outcomes of gout and hyperuricemia. Am

In: Isselbacher KJ, Braunwald E, Wilson JD, Martin JB, Fauci

J Med 1979; 67: 7482

AS, Kasper DS (eds). Harrisons Principles of Internal Medicine.

12. Berger L, Yu TF. Renal function in gout. Am J Med 1975;

McGraw-Hill Inc, New York, 1994; 20792088

59: 605613

6. Zollinger HU. Niere und ableitende Harnwege. In: Doerr DW,

13. Batuman V, Maesaka JK, Haddad B, Tepper E, Landy E,

Uehlinger DE (eds.) Spezielle Pathologische Anatomie. Springer

Wedeen RP. The role of lead in gout nephropathy. N Engl

Verlag, Berlin, 1966; 282289

J Med 1981; 304 (9): 520523

7. Fineberg SK, Altschul A. The nephropathy in gout. Ann Intern

14. Prior IA, Rose BS, Harvey HP, Davidson F. Hyperuricemia,

Med 1956; 44: 11821195

gout and diabetic abnormality in Polynesian people. Lancet

8. Chonko AM, Richardson WP. Urate and uric acid nephropathy,

1966: 333338

cystinosis, and oxalosis. In: Tisher CC, Brenner BM (eds) Renal

15. Emmerson BT. The management of gout. N Engl J Med 1996;

PathologyWith Clinical and Functional Correlations; Vol. II.

Lippincott Company, Philadelphia: 1994, 2nd edn: 14131441 334 ( 7): 445451

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Return by Nicholas SparksДокумент282 страницыThe Return by Nicholas SparksClarisse Esmores95% (19)

- NCP Ineffective Tissue PerfusionДокумент4 страницыNCP Ineffective Tissue PerfusionKristine Maghari83% (6)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- 2a Reference Ranges 2008 PDFДокумент122 страницы2a Reference Ranges 2008 PDF'Daniela SalgadoОценок пока нет

- Ela 5100 SpecДокумент1 страницаEla 5100 SpecAbdul Muin RitongaОценок пока нет

- Diamond SmartLyteДокумент2 страницыDiamond SmartLyteAbdul Muin RitongaОценок пока нет

- CatalogueДокумент43 страницыCatalogueAbdul Muin RitongaОценок пока нет

- Levey Jennings & Westgard RulesДокумент31 страницаLevey Jennings & Westgard RulesMyra Kiriyuu100% (2)

- CA-660 CA-650 4p ENДокумент4 страницыCA-660 CA-650 4p ENanisaaanrОценок пока нет

- Hematology Derui BCC3000 PDFДокумент2 страницыHematology Derui BCC3000 PDFAbdul Muin RitongaОценок пока нет

- BioSystems A-15 Analyzer - Maintenance Manual PDFДокумент23 страницыBioSystems A-15 Analyzer - Maintenance Manual PDFGarcía XavierОценок пока нет

- Brochure VesMatic-Cube Data Sheet MKT-10-1087Документ2 страницыBrochure VesMatic-Cube Data Sheet MKT-10-1087Abdul Muin RitongaОценок пока нет

- Coatron M4 08-0544Документ2 страницыCoatron M4 08-0544Abdul Muin RitongaОценок пока нет

- Final2 Rec For ThromboelastoДокумент5 страницFinal2 Rec For ThromboelastoAbdul Muin RitongaОценок пока нет

- Patogenesis GoutДокумент8 страницPatogenesis GoutShalini ShanmugalingamОценок пока нет

- TegДокумент5 страницTegAbdul Muin RitongaОценок пока нет

- Bedside Assessment of Coagulation Disorders in PostДокумент2 страницыBedside Assessment of Coagulation Disorders in PostAbdul Muin RitongaОценок пока нет

- Predictors of Transfusion of Packed Red Blood Cells PDFДокумент7 страницPredictors of Transfusion of Packed Red Blood Cells PDFAbdul Muin RitongaОценок пока нет

- JE Hemato 2 MuinДокумент2 страницыJE Hemato 2 MuinAbdul Muin RitongaОценок пока нет

- JE Hemato 2 MuinДокумент2 страницыJE Hemato 2 MuinAbdul Muin RitongaОценок пока нет

- Daftar Pustaka BenerДокумент4 страницыDaftar Pustaka BenerAbdul Muin RitongaОценок пока нет

- Predictors of Transfusion of Packed Red Blood Cells PDFДокумент7 страницPredictors of Transfusion of Packed Red Blood Cells PDFAbdul Muin RitongaОценок пока нет

- Test 1Документ4 страницыTest 1Thư NguyễnОценок пока нет

- Dyestone Green MX SDS SA-0172-01Документ5 страницDyestone Green MX SDS SA-0172-01gede aris prayoga mahardikaОценок пока нет

- Respirator Cartridge ChartДокумент2 страницыRespirator Cartridge ChartRanto GunawanОценок пока нет

- Soal News ItemДокумент11 страницSoal News ItemYehezkiel Rivaldo Widjaya100% (1)

- Behruz Makhmudov - All Printables March 2021Документ6 страницBehruz Makhmudov - All Printables March 2021Behruz MakhmudovОценок пока нет

- 2021 重症核心課程CRRT Dose and Prescription-NEW Ver1.0Документ63 страницы2021 重症核心課程CRRT Dose and Prescription-NEW Ver1.0Andy DazОценок пока нет

- Gurdjieff S Sexual Beliefs and PДокумент11 страницGurdjieff S Sexual Beliefs and PDimitar Yotovski0% (1)

- Module 1: Health AssessmentДокумент16 страницModule 1: Health AssessmentAmberОценок пока нет

- Physiological Psychology - Critique PaperДокумент2 страницыPhysiological Psychology - Critique PaperJoan Marie LucenaОценок пока нет

- Abruptio Placenta: Prepared By: Claire Alvarez Ongchua, RNДокумент42 страницыAbruptio Placenta: Prepared By: Claire Alvarez Ongchua, RNclaireaongchua1275100% (2)

- BGS Interim ReportДокумент8 страницBGS Interim ReportGaurav KishoreОценок пока нет

- Good Morning Class! February 10, 2021: Tle-CarpentryДокумент57 страницGood Morning Class! February 10, 2021: Tle-CarpentryGlenn Fortades SalandananОценок пока нет

- EpidimologyДокумент78 страницEpidimologyWeji ShОценок пока нет

- Boykin & Schoenhofer's Theory of Nursing As CaringДокумент1 страницаBoykin & Schoenhofer's Theory of Nursing As CaringErickson CabassaОценок пока нет

- Goodman, Ashley SignedДокумент1 страницаGoodman, Ashley SignedAshley GoodmanОценок пока нет

- Philadelphia Adventist ChurchДокумент2 страницыPhiladelphia Adventist ChurchMETALОценок пока нет

- White Room MINIMUM REQUIREMENTS FOR CONTROLLING ENVIRONMENTAL CONTAMINATION OF COMPONENTSДокумент12 страницWhite Room MINIMUM REQUIREMENTS FOR CONTROLLING ENVIRONMENTAL CONTAMINATION OF COMPONENTS57641Оценок пока нет

- Code of Practice For Metal Decking and Stud Welding 2014Документ30 страницCode of Practice For Metal Decking and Stud Welding 2014joe briffaОценок пока нет

- OPPro Psychometric PropertiesДокумент3 страницыOPPro Psychometric PropertiesShaniceОценок пока нет

- Open Stabilization of Acute Acromioclavicular Joint Dislocation Using Twin Tail Tightrope SystemДокумент6 страницOpen Stabilization of Acute Acromioclavicular Joint Dislocation Using Twin Tail Tightrope SystemParaliov TiberiuОценок пока нет

- Spirituality Among Retired PersonsДокумент4 страницыSpirituality Among Retired PersonsEditor IJTSRDОценок пока нет

- Details of Flammable, Explosive and Hazardous Materials Identified For Risk Assessment Details of Storage Unit Storage Press. & TempДокумент42 страницыDetails of Flammable, Explosive and Hazardous Materials Identified For Risk Assessment Details of Storage Unit Storage Press. & TempNageswar MakalaОценок пока нет

- Margaret Naumburg PapersДокумент145 страницMargaret Naumburg PapersmarianaОценок пока нет

- Ethics Case StudyДокумент4 страницыEthics Case StudycasscactusОценок пока нет

- V6 - Health CS VC Collectors 22.08.2023Документ92 страницыV6 - Health CS VC Collectors 22.08.2023MdnowfalОценок пока нет

- Asr 1Документ40 страницAsr 1nadia viОценок пока нет

- Ebook Drmanjujain 2Документ286 страницEbook Drmanjujain 2Himani ShahОценок пока нет

- Using in Children and Adolescents: BenzodiazepinesДокумент4 страницыUsing in Children and Adolescents: BenzodiazepinesEunike KaramoyОценок пока нет