Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

(GR) Ignacio V Director of Lands (1960)

Загружено:

Jethro Koon0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

24 просмотров4 страницы-

Оригинальное название

(GR) Ignacio v Director of Lands (1960)

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документ-

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

24 просмотров4 страницы(GR) Ignacio V Director of Lands (1960)

Загружено:

Jethro Koon-

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 4

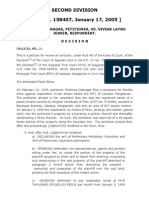

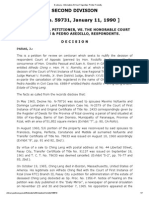

[ G.R. No.

L12958, May 30, 1960 ]

FAUSTINO IGNACIO, APPLICANT AND APPELLANT, VS. THE

DIRECTOR OF LANDS AND LAUREANO VALERIANO,

OPPOSITORS AND APPELLEES.

D E C I S I O N

MONTEMAYOR, J.:

Faustino Ignacio is appealing the decision of the Court of First Instance of Rizal,

dismissing his application for the registration of a parcel of land.

On January 25, 1950, Ignacio filed an application for the registration of a parcel of

land (mangrove), situated in barrio Gasac, Navotas, Rizal, with an area of 37,877

square meters. Later, he amended his application by alleging among others that he

owned the parcel applied for by right of accretion. To the application, the Director of

Lands, Laureano Valeriano and Domingo Gutierrez filed oppositions. Gutierrez later

withdrew his opposition. The Director of Lands claimed the parcel applied for as a

portion of the public domain, for the reason that neither the applicant nor his

predecessorininterest possessed sufficient title thereto, not having acquired it

either by composition title from the Spanish government or by possessory

information title under the Royal Decree of February 13, 1894, and that he had not

possessed the same openly, continuously and adversely under a bonafide claim of

ownership since July 26, 1894. In his turn, Valeriano alleged that he was holding

the land by virtue of a permit granted him by the Bureau of Fisheries, issued on

January 13, 1947, and approved by the President.

It is not disputed that the land applied for adjoins a parcel owned by the applicant

which he had acquired from the Government by virtue of a free patent title in 1936.

It has also been established that the parcel in question was formed by accretion and

alluvial deposits caused by the action of the Manila Bay which borders it on the

southwest. Applicant Ignacio claims that he had occupied the land since 1935,

planting it with apiapi trees, and that his possession thereof had been continuous,

adverse and public for a period of twenty years until said possession was disturbed

by oppositor Valeriano.

On the other hand, the Director of Lands sought to prove that the parcel is

foreshore land% covered by the ebb and flow of the tide and, therefore, formed part

of the public domain.

After hearing, the trial court dismissed the application, holding that the parcel

formed part of the public domain. In his appeal, Ignacio assigns the following

errors:

"I. The lower court erred in holding that the land in question, altho an

accretion to the land of the applicantappellant, does not belong to him

but forms part of the public domain.

"II. Granting that the land in question forms part of the public domain,

the lower court nevertheless erred in not declaring the same to be the

property of the applicantappellant, the said land not being necessary for

any public use or purpose and in not ordering at the same time its

registration in the name of applicantappellant in the present

registration proceedings.

"III. The lower court erred in not holding that the land in question now

belongs to the applicantappellant by virtue of acquisitive prescription,

the said land having ceased to be of the public domain and became the

private or patrimonial property of the State.

"IV. The lower court erred in not holding that the oppositor Director of

Lands is now in estoppel from claiming the land in question as a land of

the public domain."

Appellant contends that the parcel belongs to him by the law of accretion, having

been formed by gradual deposit Inaction of the Manila Bay, and he cites Article 457

of the New Civil Code (Article 366, Old Civil Code), which provides that:

"To the owners of lands adjoining the banks of rivers belong the

accretion which they gradually receive from the effects of the current of

the waters."

The article cited is clearly inapplicable because it refers to accretion or deposits on

the banks of rivers, while the accretion in the present case was caused by action of

the Manila Bay.

Appellant next contends that Articles 1, 4 and 5 of the Law of Waters are not

applicable because they refer to accretions formed by the sea, and that Manila Bay

cannot be considered as a sea. We find said contention untenable. A bay is a part of

the sea, being a mere indentation of the same:

"Bay.An opening into the land where the water is shut in on all sides

except at the entrance an inlet of the sea an arm of the sea, distinct

from a river, a bending or curbing of the shore of the sea or of a lake." 7

C.J. 10131014 (Cited in Francisco, Philippine Law of Waters and Water

Rights p. 6)

Moreover, this Tribunal has in some cases applied the Law of Waters on Lands

bordering Manila Bay. (See the cases of Ker & Co. vs. Cauden, 6 Phil., 732,

involving a parcel of land bounded on the sides by Manila Bay, where it was held

that such land formed by the action of the sea is property of the State Francisco

vs. Government of the P.I., 28 Phil., 505, involving a land claimed by a private

person and subject to the ebb and flow of the tides of the Manila Bay).

Then the applicant argues that granting that the land in question formed part of

the public domain, having been gained from the sea, the trial court should have

declared the same no longer necessary for any public use or purpose, and therefore,

became disposable and available for private ownership. Article 4 of the Law of

Waters of 1866 reads thus:

"Art. 4. Lands added to the shores by accretions and alluvial deposits

caused by the action of the sea, form part of the public domain. When

they are no longer washed by the waters of the sea and are not

necessary for purposes of public utility, or for the establishment of

special industries, or for the coastguard service, the Government shall

declare them to be the property of the owners of the estates adjacent

thereto and as increment thereof."

Interpreting Article 4 of the Law of Waters of 1866, in the case of Natividad vs.

Director of Lands, (CA) 37 Off. Gaz., 2905, it was there held that:

"Article 4 of the Law of Waters of 1866 provides that when a portion of

the shore is no longer washed by the waters of the sea and is not

necessary for purposes of public utility, or for the establishment of

special industries, or for coastguard service, the government shall

declare it to be the property of the owners of the estates adjacent

thereto and as an increment thereof. We believe that only the executive

and possibly the legislative departments have the authority and the

power to make the declaration that any land so gained by the sea, is not

necessary for purposes of public utility, or for the establishment of

special industries, or for coastguard service. If no such declaration has

been made by said departments, the lot in question forms part of the

public domain." (Natividad vs. Director of Lands, supra.)

The reason for this pronouncement, according to this Tribunal in the case of Vicente

Joven y Monteverde vs. Director of Lands, 93 Phi]., 134, (cited in Velayo's Digest,

Vol. I, p. 52).

"* * * is undoubtedly that the courts are neither primarily called upon,

nor indeed in a position to determine whether any public land are to be

used for the purposes specified in Article 4 of the Law of Waters."

Consequently, until a formal declaration on the part of the Government, through

the executive department or the Legislature, to the effect that the land in question

is no longer needed for coast guard service, for public use or for special industries,

they continue to be part of the public domain, not available for private

appropriation or ownership.

Appellant next contends that he had acquired the parcel in question through

acquisitive prescription, having possessed the same for over ten years. In answer,

suffice it to say that land of the public domain is not subject to ordinary

prescription. In the case of Insular Government vs. Aldecoa & Co., 19 Phil., 505,

this Court said:

"The occupation or material possession of any land formed upon the

shore by accretion, without previous permission from the proper

authorities, although the occupant may have held the same as owner for

seventeen years and constructed a wharf on the land, is illegal and is a

mere detainer, inasmuch as such land is outside of the sphere of

commerce it pertains to the national domain it is intended for public

uses and for the benefit of those who live nearby."

We deem it unnecessary to discuss the other points raised in the appeal.

In view of the foregoing, the appealed decision is hereby affirmed, with costs.

Paras,C.J.,Bengzon,Padilla,Bautista Angelo, Labrador,Concepcion, Barrera, and

GutierrezDavid,JJ., concur.

Source: Supreme Court ELibrary

This page was dynamically generated

by the ELibrary Content Management System (ELibCMS)

Вам также может понравиться

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Sample Website Development AgreementДокумент4 страницыSample Website Development AgreementTochi Krishna Abhishek100% (1)

- PresumptionsДокумент2 страницыPresumptionsAllyssa Paras Yandoc0% (1)

- Article VI. Party-List Representation - Coalition of Associations of Senior Citizens vs. COMELEC (Case Digest)Документ2 страницыArticle VI. Party-List Representation - Coalition of Associations of Senior Citizens vs. COMELEC (Case Digest)Ellie HarmonieОценок пока нет

- Salient Features - ROCДокумент78 страницSalient Features - ROCRon NasupleОценок пока нет

- Case Digest: Imbong vs. Ochoa, JR PDFДокумент14 страницCase Digest: Imbong vs. Ochoa, JR PDFJetJuárezОценок пока нет

- Case DigestДокумент3 страницыCase DigestTeacherEli33% (3)

- Affidavit of Undertaking and WaiverДокумент1 страницаAffidavit of Undertaking and WaiverTumasitoe Bautista Lasquite50% (2)

- 104 - City Government of Quezon City v. ErictaДокумент3 страницы104 - City Government of Quezon City v. Erictaalexis_beaОценок пока нет

- River Island Ownership DisputeДокумент2 страницыRiver Island Ownership DisputeJudiel Pareja100% (1)

- (GR) Domagas V Jensen (2005)Документ13 страниц(GR) Domagas V Jensen (2005)Jethro KoonОценок пока нет

- (GR) Cortes V City of Manila (1908)Документ3 страницы(GR) Cortes V City of Manila (1908)Jethro KoonОценок пока нет

- (GR) Republiv V CA & Tancino (1984)Документ6 страниц(GR) Republiv V CA & Tancino (1984)Jethro KoonОценок пока нет

- (GR) Ching V CA (1990)Документ7 страниц(GR) Ching V CA (1990)Jethro KoonОценок пока нет

- (GR) Equatorial V Mayfair (2001)Документ38 страниц(GR) Equatorial V Mayfair (2001)Jethro Koon100% (1)

- (GR) Baricuatro V CA (2000)Документ17 страниц(GR) Baricuatro V CA (2000)Jethro KoonОценок пока нет

- (GR) Spouses Portic V Cristobal (2005)Документ9 страниц(GR) Spouses Portic V Cristobal (2005)Jethro KoonОценок пока нет

- (GR) Hilario V City of Manila (1967)Документ21 страница(GR) Hilario V City of Manila (1967)Jethro KoonОценок пока нет

- (GR) Binalay V Manalo (1991)Документ11 страниц(GR) Binalay V Manalo (1991)Jethro KoonОценок пока нет

- (GR) Zapata V Director of Lands (1962)Документ3 страницы(GR) Zapata V Director of Lands (1962)Jethro KoonОценок пока нет

- (GR) Titong V CA (1998)Документ10 страниц(GR) Titong V CA (1998)Jethro KoonОценок пока нет

- (GR) Baes V CA (1993)Документ4 страницы(GR) Baes V CA (1993)Jethro KoonОценок пока нет

- (GR) BA Finance V CA (1996)Документ10 страниц(GR) BA Finance V CA (1996)Jethro KoonОценок пока нет

- (GR) PEZA V Fernandez (2001)Документ10 страниц(GR) PEZA V Fernandez (2001)Jethro KoonОценок пока нет

- (GR) Bishop of Cebu V Mangaron (1906)Документ10 страниц(GR) Bishop of Cebu V Mangaron (1906)Jethro KoonОценок пока нет

- (GR) Vda de Aviles V CA (1996)Документ8 страниц(GR) Vda de Aviles V CA (1996)Jethro KoonОценок пока нет

- (GR) Sandejas V Robles (1948)Документ3 страницы(GR) Sandejas V Robles (1948)Jethro KoonОценок пока нет

- (GR) Heirs of Durano V Uy (2000)Документ23 страницы(GR) Heirs of Durano V Uy (2000)Jethro KoonОценок пока нет

- (GR) de La Paz V Panis (1995)Документ7 страниц(GR) de La Paz V Panis (1995)Jethro KoonОценок пока нет

- (GR) Pingol V CA (1993)Документ10 страниц(GR) Pingol V CA (1993)Jethro KoonОценок пока нет

- (GR) Vda de Nazareno V CA (1996)Документ8 страниц(GR) Vda de Nazareno V CA (1996)Jethro KoonОценок пока нет

- (GR) Floreza V Evangelista (1980)Документ7 страниц(GR) Floreza V Evangelista (1980)Jethro KoonОценок пока нет

- German Mgt. vs. CAДокумент3 страницыGerman Mgt. vs. CAennaonealОценок пока нет

- (GR) Alviola V CA (1998)Документ7 страниц(GR) Alviola V CA (1998)Jethro KoonОценок пока нет

- (GR) Pleasantville V CA (1996)Документ12 страниц(GR) Pleasantville V CA (1996)Jethro KoonОценок пока нет

- (GR) Hernandez V DBP (1976)Документ4 страницы(GR) Hernandez V DBP (1976)Jethro KoonОценок пока нет

- Manotok Realty v. TecsonДокумент4 страницыManotok Realty v. TecsonmisterdodiОценок пока нет

- (GR) Heirs of Olviga V CA (1993)Документ5 страниц(GR) Heirs of Olviga V CA (1993)Jethro KoonОценок пока нет

- (GR) JM Tuason V Vda de Lumanlan (1968)Документ5 страниц(GR) JM Tuason V Vda de Lumanlan (1968)Jethro KoonОценок пока нет

- Wayne Brandt v. Board of Cooperative Educational Services, Third Supervisory District, Suffolk County, New York, Edward J. Murphy and Dominick Morreale, 820 F.2d 41, 2d Cir. (1987)Документ6 страницWayne Brandt v. Board of Cooperative Educational Services, Third Supervisory District, Suffolk County, New York, Edward J. Murphy and Dominick Morreale, 820 F.2d 41, 2d Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Atty. Chico - Civil Law - Torts and DamagesДокумент56 страницAtty. Chico - Civil Law - Torts and DamagesErick Paul de VeraОценок пока нет

- Only The RFAM (Rolando Florida Alfredo Myrna) )Документ2 страницыOnly The RFAM (Rolando Florida Alfredo Myrna) )Vernon ArquinesОценок пока нет

- Host Agreement Between Good Chemistry and WorcesterДокумент8 страницHost Agreement Between Good Chemistry and WorcesterAllison ManningОценок пока нет

- Rule of Law Principles: Equality, Predictability and GeneralityДокумент3 страницыRule of Law Principles: Equality, Predictability and Generalitymaksuda monirОценок пока нет

- People V Largo, GR No. L-4913Документ4 страницыPeople V Largo, GR No. L-4913Jae MontoyaОценок пока нет

- Rome Convention. ContractsДокумент15 страницRome Convention. ContractsBipluv JhinganОценок пока нет

- FDLE Investigative Report Into Dye's Allegations Against Naples Mayor Heitmann - April 2021Документ2 страницыFDLE Investigative Report Into Dye's Allegations Against Naples Mayor Heitmann - April 2021Omar Rodriguez Ortiz100% (1)

- Not PrecedentialДокумент6 страницNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- G.R. No. L-11002 Supreme Court Case on Omission of Taxable PropertyДокумент5 страницG.R. No. L-11002 Supreme Court Case on Omission of Taxable PropertyCJ N PiОценок пока нет

- Act No. 2 of 2023: Legal Supplement Part A To The "Trinidad and Tobago Gazette", Vol. 62, NДокумент7 страницAct No. 2 of 2023: Legal Supplement Part A To The "Trinidad and Tobago Gazette", Vol. 62, NERSKINE LONEYОценок пока нет

- Dwnload Full Cutlip and Centers Effective Public Relations 11th Edition Broom Solutions Manual PDFДокумент36 страницDwnload Full Cutlip and Centers Effective Public Relations 11th Edition Broom Solutions Manual PDFlesliepooleutss100% (13)

- Joint Venture Agreement - Yannfil & Motion Express PNG LTD - 2020Документ14 страницJoint Venture Agreement - Yannfil & Motion Express PNG LTD - 2020Matthew Tom KaebikaeОценок пока нет

- Memo For All RDs On Memo Order No 17-2520 Series of 2017 PDFДокумент1 страницаMemo For All RDs On Memo Order No 17-2520 Series of 2017 PDFCatherine BenbanОценок пока нет

- Cyber LawДокумент7 страницCyber LawPUTTU GURU PRASAD SENGUNTHA MUDALIAR100% (4)

- Colreg 1972 PDFДокумент74 страницыColreg 1972 PDFsidd1007Оценок пока нет

- Smartfind E5 g5 User ManualДокумент49 страницSmartfind E5 g5 User ManualdrewlioОценок пока нет

- Deemed Exports in GSTДокумент3 страницыDeemed Exports in GSTBharat JainОценок пока нет

- Yojana January 2024Документ64 страницыYojana January 2024ashish agrahariОценок пока нет

- Bulding Regulations PDF ADK 1998Документ0 страницBulding Regulations PDF ADK 1998Sugumar N ShanmugamОценок пока нет