Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

The Asian Woman As Representation of Western Fantasies

Загружено:

NataLina0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

136 просмотров13 страницIn recent decades Asia has become a center of attraction for many Western tourists. There is even a strong racial preference towards Asian women known as "asiaphilia" This clear sexual preference of Asian females among some Westerners is also known as the so-called "yellow fever"

Исходное описание:

Оригинальное название

The Asian Woman as Representation of Western Fantasies

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документIn recent decades Asia has become a center of attraction for many Western tourists. There is even a strong racial preference towards Asian women known as "asiaphilia" This clear sexual preference of Asian females among some Westerners is also known as the so-called "yellow fever"

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

136 просмотров13 страницThe Asian Woman As Representation of Western Fantasies

Загружено:

NataLinaIn recent decades Asia has become a center of attraction for many Western tourists. There is even a strong racial preference towards Asian women known as "asiaphilia" This clear sexual preference of Asian females among some Westerners is also known as the so-called "yellow fever"

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 13

Fachbereich 05 Department of English and Linguistics

Seminar: The American Melodrama

Leitung: Dr. Sonja Georgi

Sommersemester 2013

The Asian Woman as Representation of Western Fantasies

Natalie Tanja Pehl B.Ed. (7. Semester)

Baumgartenstrae 11 Englisch, Germanistik,

55543 Bad Kreuznach Philosophie

Telefon: 0671/9799715

Email: natalie_tanja@yahoo.de

Table of Contents

Table of Contents ........................................................................................... 2

1. Introduction ................................................................................................. 1

2. The Asian Woman as Representation of Western Fantasies ...................... 2

3. The Image of the Traditional Geisha ........................................................... 3

4. The China Dolls ........................................................................................ 4

4.1 Cho-Cho San as an Example for the China Doll ................................. 5

4.2 Suzie Wong ........................................................................................... 6

5. Conclusion .................................................................................................. 7

6. Work Cited .................................................................................................. 9

1

1. Introduction

Oriental Sex as White Mens Fantasy?

In recent decades Asia has become a center of attraction for many

Western tourists. There is even a strong racial preference towards Asian

women known as Asiaphilia (Tan 33) expressing the Westerners Asian

fetish. This clear sexual preference of Asian females among some Westerners

is also known as the so-called Yellow Fever (Eng 158). Accordingly, it is no

longer a secret that there is a big business in Asia regarding sex tourism and

many Western men even contact partner agencies to search for a partner in

Asia. In an interview, an Asian woman reported that men with the Asian

fetish expect women to be sex-craved housekeepers and that many Asian

women are offended that they are wanted simply because they are Asian

(Tan 33).

Those observations can be easily related to the attraction between Asian

women and Western men. Whereas white men are attracted to the

exoticness of the Asian woman, the Asian woman reciprocates this attraction

towards them. This observation already inherits that people often tend to be

attracted to something different.

Therefore this paper will deal with the Asian-American stereotype of the

so-called China Doll. To understand the establishment of that stereotype

better, the image of the traditional Geisha will be explained in more detail.

Furthermore it will try to answer the following question: Why is the Western

depiction of the East in many cases limited to that stereotype of the Asian

woman? As a detailed example for the China Doll this paper will refer to the

Geisha Cho-Cho San of Puccinis opera Madame Butterfly and the Chinese

prostitute Suzy Wong. Thus, it wants to state that the stereotypical view on the

Asian woman represents the Oriental fantasies of the West and has to suffer

from constrictions due to the Wests limited depiction of the East.

Consequently, the China Doll is restricted to her stereotype due to racial

prejudices and is captured in her socially constructed identity.

2

2. The Asian Woman as Representation of Western

Fantasies

According to the literary critic and post-colonial theorist Edward Said,

the term Orientalism was established in the 19

th

century and can be

discussed and analyzed as the corporate constitution for dealing with the

Orient (Trefflich 6).

There are three concepts of how to define Orientalism. First of all,

Orientalism is considered as an academic discipline. Correspondingly, an

Orientalist is anyone who teaches or writes about the Orient (e.g. historians,

sociologists). Moreover, Orientalism can be used as a style of thought, namely

positioning the Orient in juxtaposition to the Occident. Thirdly, Orientalism is a

Western style of dominating, restructuring and having authority over the

Orient, such as power structures (military, scientific, and political institutions).

In this connection, Orientalism is a depiction of the orient which is constructed

(cf. Said 88). According to that, the second and third definitions are relevant

for this paper.

About The World of Suzie Wong, a movie which I will exemplify later,

one author said, the film title suggests that it is an Orientalist text in Edward

Saids sense of the term [and] this text constructs a vision of the Orient and

implicitly justifies Western exploitation of that world (Feng 41). Accordingly, it

clarifies that the Western vision of the Orient is socially constructed. The

Western depiction of the East is not naturally developed but still necessary as

an ideological supplement (Yegenoglu 15) to the dominating power of the

West.

Consequently, the imagination of the dominant West and the

submissive East is easily created. Based on the historical past, people from

the Far East are often associated with submissiveness and loyalty to their

regime. According to Said, the West represents the Occident and the East the

Orient (cf. Said 88). Despite the Eastern subordination, the Orient had an

important meaning in help[ing] to define Europe (or the West) as its

contrasting image, idea, personality [and] experience (Said 87ff.).

Subsequently, Said identifies how the essentializing and dichotomizing

discourse of Orientalism functions in a complex but systematic way as an

element of colonial domination (Yegenoglu 15). This proves the necessity of

the East to the West and that the East enables the West to define its power.

3

Comparing to that description, the relationship between East and West is

similar to the Confucian symbolism of Yin and Yang.

The yin and yang symbol merits fuller discussion. On one side of the

circle is the yin (dark, cold, moist, feminine, intuitive) and on the other

side is the yang (bright, hot, dry, masculine, rational). [] The harmony

or balance of the complementary qualities of yin and yang makes a

thing what it is properly in its perfection. If things get out of balance,

then an undesirable state of affairs results (Gualtieri 62).

Thus, East and West stand for two counterparts fitting to each other.

The West as masculine part is drawn to the femininity of the East and both

feel the desire to unify with each other. The center of attraction is the

exoticness and fascination by the difference of the Eastern features which is

the base to invent certain stereotypes and idealized images in our minds.

Connected with Western clichs of the orient like the imagination of the

harem for example, the Eastern image is contributed with sexuality and

eroticism. Moreover, the harem fantasy [] is presented in Orientalism only

as a Western invention (Varisco 160). As a consequence, Western minds

establish the fantasy of fulfilling their desires in the Orient. Oriental women

symbolize the Western male fantasies of power and sexual access because

they express unlimited sensuality, they are more or less stupid, and above all

they are willing (Teo 242). Therefore, the Asian woman is often connected

with those expectations and represents an ideal of the Western desires.

3. The Image of the Traditional Geisha

Being an essential part of traditional Japanese culture, the Geishas

were seen of high reputation and social rank in Asian society. The word Gei-

sha etymologically derives from the word gei which means art in Japanese

language and the word sha stands for doer. Combining those terms

together, the word Geisha means performing artist (King 141). This

translation already reveals that the profession of the Geisha is focused

primarily on artistic fields and was known as a good dancer, singer, musical

instrument player, conversationalist and a wonderful hostess (Kapunan 6).

The Chinese equivalent of the Geisha is the so-called China Doll or Lotus

Blossom. Mistakenly, the profession of the Geisha is often connected with

prostitution but a geisha was a professional entertainer not necessarily

4

available for sexual relationships (Poole 167). This prejudice may derive from

the observation that the Geisha sells her artistic services such as music and

dance and a prostitute sells herself for sexual actions. Moreover, Geishas

were beautiful, well-educated in many subjects, and able to provide the social

and intimate companionship that many of the Yakuza and nobility demanded

of themselves and others (51 Ujiie) which enabled them to get easy access to

influential men from higher classes and reputable working positions.

In contemporary Japanese culture, the existence of Geishas has

become very rare. Nowadays, there are more other alternative job

opportunities for women which makes the profession of being a Geisha less

attractive. Still, the image of the Geisha embodies the traditional values of

Japanese culture.

4. The China Dolls

The Asian-American stereotype of the China Doll is also called Lotus

Blossom or Geisha Girl (as Japanese equivalent). Analyzing the names, we

get obvious hints for the upcoming definition. Referring to this stereotypical

image the Chinese American actress Mary Mammon said: In this particular

case being small was a good thing. They thought we were very cute and so

daintyIn other words, we were little Chinadolls. (Chun 68)

Already the word doll indicates features such as fragility, softness,

beauty and also cuteness. Those abilities can be projected easily on the

image of this female figure. The constant assertion [] of the [Asian] woman

as an infantilized, toy-like creature relegates her to the realm of childhood and

fantasy (Poole 171). On the other hand a doll also serves as a toy which

implies the subservient qualities the China Doll stands for. Relating to that

observation, Asian women in Asia or the United States are seen as

submissive, compliant and eager to please their men (Danico 134).

Additionally, therefore the China Doll is often compared in terms with

prostitutes, as dainty sex objects (Espiritu 107).

Referring to Buddhist symbolism, the lotus blossom represents

immaculate purity, love and compassion (Beer 170) which emphasizes the

pure nature and innocent features of the China Doll.

5

Generally, Asian American Females are characterized as childlike,

fragile and innocent like in Chinadolls, Polynesian Babies, and Asian

Thumbelinas (Ruth 213). Portrayed as nearly supernatural beings, is also a

reference that the image of the China Doll can only be a cultural product and

as such is prone to manipulation (Poole 171). The first Chinese American

actress portraying this stereotype was Anna Mae Wong.

4.1 Cho-Cho San as an Example for the China Doll

The protagonist of Giacomo Puccinis opera Madame Butterfly (1904)

and the same-named short story version by John Luther Long (1898) is the

young Japanese geisha Cho-Cho San. She is a typical example for the

stereotype of the Geisha Girl or China Doll (as the Chinese equivalent).

Already in her name Cho-Cho San, the image of the Geisha is reflected, since

the Japanese word Cho-Cho means butterfly. The butterfly image has the

following meaning in Japanese tradition:

The Japanese [...] believe that a single butterfly is a symbol for young

womanhood, and two symbolize a successful marriage. Jade

Butterflies carved by Asian artisans represent triumphant love (Green

33).

According to this description, there are several parallels between

Cho-Cho San and the butterfly symbol. Being only 15 years old, Cho-Cho San

is indeed very young and inexperienced when she marries Pinkerton. She is

described as a rather silly girl, who quickly and fatefully gives up her family

ties and religion for the sake of love without realizing the temporary

arrangement (Poole 170), which demonstrates her naivety throughout the

story. Moreover, her inexperience and naivety can also be related to her

innocence and pureness which are typical features of the China Doll

stereotype. Additionally, Cho-Cho San is eager to please Pinkerton and she is

willing to do her best for a successful marriage with him. Referring to the

oriental view on the relationship between East and West, Lieutenant

Pinkerton symbolizes the dominant, masculine America, while the fragile,

exotic beauty Cho-Cho-San stands for the subordinated, feminized Asia

(Yoshihara 4). Nevertheless Cho-Cho-San represents a special kind of the

China Doll. On the one hand, she is willing to adapt to Pinkertons way of life

and his American culture, but on the other hand she also wants to keep her

Japanese traditions. Pinkerton is attracted to her exoticness and her Asian

6

mentality but on the other hand he wants to combine both cultures and tries to

transform his doll Cho-Cho-San to an American Geisha. This reveals for

example, when Pinkerton wants her to convert her belief to Christianity.

Moreover, their child actually represents the mixture of the benefits of both

cultures. When her child is sleeping, it is said, that he was good as a

Japanese baby, and as good-looking as an American one (Long 381). She

trusts unconditionally in Pinkertons return to her and believes in the triumph of

their love and reunification. When Pinkerton is absent, no daintier creature

need one ever wish to see than this bride awaiting anew the coming of her

husband (Long 70).

The ability of a butterflys fragility is also shown when Cho-Cho San

cannot bear the return of Pinkerton and his new wife to Japan. Receiving a

telegram addressed to Pinkerton that his new wife wants to take her child

away, Cho-Cho San commits suicide afterwards, which indicates her

desperation and inability to cope with the situation. Consequently, Cho-Cho

San also embodies the stereotypical image of the tragic heroine that has

unrightfully been betrayed (Poole 174) and sees death as the only solution for

her misery.

4.2 Suzie Wong

1

The novel The World of Suzie Wong (1957) by Richard Mason is a

famous novel which has also been adapted to a Broadway play (1958) and

also a movie (1960) (cf. Feng 42f.). The film version deals with the Chinese

prostitute Suzy Wong (Nancy Kwan) living in Hong Kong who meets the

British artist Robert Lomax (William Holden). Later a romance develops

between them.

In the movie, Suzie is also presented as young and naive but she is

also realistic and wants to be independent. Although she is not educated that

well and cannot read and write, she prefers working as a prostitute to be

financially independent and to be able to care for her child.

The movie has received critique, since The World of Suzie Wong is

indeed a classic racist, sexist text, [since] the only Chinese Women we

encounter are prostitutes (Feng 43). Moreover, the image of the China Doll

stereotype is contrasted due to Roberts friend Kay, who is excoriated as a

1

In my paper I will refer to the movie version of The World of Suzie Wong.

7

scheming white woman; in comparison, the submissive Suzie comes to

embody desirable feminine attributes (Feng 42).

In one scene a sailor beats Suzie, when she refuses having sex with

him. Afterwards Robert rescues her but Suzie wants to tell her friends that

Robert was the one who hit her. Surprisingly, her friends react in a positive

way, since they believe that Robert must be crazy in love with her. By

watching that scene the spectator is simultaneously reassured that Asian

women want to be beaten and allowed to displace revulsion onto the Orient

(Feng 42). Due to that point, Suzies submissiveness and weakness is

emphasized further. Moreover, her inferiority reveals in the final love scene,

when Suzie pledges to stay with her American man until he says Suzie, go

away (Cho 542). Strikingly, Robert does not want to dominate Suzy actively,

Suzie rather decides voluntarily that she wants to be dominated by him.

That scene emphasizes the Western imagination that Asian women

accept their inferiority towards men naturally and that they are eager to please

them. It also represents the male desire to be adored by their women which

enhances their male consciousness.

5. Conclusion

This paper wanted to convey that the Western perception of the East is

restricted to a certain Asian stereotype. Famous actresses like Nancy Kwan or

Anna Mae Wong were very limited in the variety of their fields of acting, since

the audience was only keen on watching them always as a portrayal of this

certain image of the Asian female. Accordingly, the actors had to be forced to

follow the audience demands since they wanted to stay in business

2

.

Furthermore, the audience seemed to be fond of this image of the Asian

female, that they were not interested in learning to know how the real Asian

woman was. This may refer to the fact that the audience longs for the oriental

exoticness because it seems to be so different to their own culture.

Nevertheless, the globalization and industrialization modernizes and affects

our cultural development. This consciousness is often neglected when we

create stereotypes in our minds and stick to them. Naturally, human beings

2

Here I am referring to an interview with Nancy Kwan in the documentary Hollywood

Chinese, by Arthur Dong.

8

tend to create images in their minds to be able to grasp things they are unable

to know in its entirety because they are too distant or abstract for them.

Therefore many people are still too narrow-minded to see beyond that

stereotypical image. Of course the Asian culture develops further and is

modernized as well, especially in countries such as Japan and China whose

economies are highly-advanced.

As a result the so-called China-Doll has to stay a doll or even a toy

for the Westerners, since the people want to keep their image of the

submissive, fragile, pure and naive Asian woman being eager to please their

men, which is very distinctive from the image of the modern emancipated

Western woman. Thus, the exoticness of the China Doll has to be preserved,

since the more the China Doll would adapt to the Western culture, the more

she would lose her exoticness. Consequently, the China Doll must preserve

her specialty in order to stay desirable in the eyes of some Westerners to

please their fantasies.

9

6. Work Cited

Primary Sources

Long, John Luther. Madame Butterfly. The Century: A Popular Quarterly

Volume 3 (1889): 374-393. Web. Digital Library Cornell Univ. 70ff.

The World of Suzie Wong. Richard Quine. Perf. William Holden, Sylvia Syms,

Laurence Naismith, Nancy Kwan, Michael Wilding. Paramount Pictures, 2010.

DVD.

Secondary Sources

Cho, Sumi K. Converging Stereotypes and the Power Complex. Critical Race

Theory: The Cutting Edge. Eds. Richard Delgado, John Stefancic.

Philadelphia: Temple UP, 2000. 542.

Chun Heyung, Gloria. Of Orphans and Warriors: Inventing Chinese Culture

and Identity. Rutgers University Press: Piscataway, 2000. 68.

Danico, Mary Yu, Ng Franklin. Asian American Issues: Contemporary

American Ethnic Issues. Westport: Greenwood Press, 2004.

Dong, Arthur. Hollywood Chinese 2007.

http://www.worlduc.com/VideoPlay2012.aspx?vid=131908 (23 June 2013).

Eng, David L. Racial Castration: Managing Masculinity in Asian America. Duke

University Press, 2005. 158.

Espiritu, Yen Le. Asian American Women and Men: Labors, Laws and Love.

Second Edition. Rowmen & Littlefield Publishers: Lanham, 2008.

Feng, Peter. Recuperating Suzie Wong: A Fans Nancy Kwan Dary.

Countervisions: Asian-American Film Criticism. Ed. Darrell Y. Iamamoto,

Sandra Liu. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2000. 41ff.

Felski, Rita. Tragic Woman. Moderne begreifen: Zur Paradoxie eines sozio-

sthetischen Deutungsmusters. Ed. Christine Magerski. Wiesbaden:

Deutscher Universitts-Verlag, 2007. 327.

10

Green Brown, Myrah. Pieced Symbols: Quilt Blocks from the Global Village.

Lark Books: New York, 2009. 33.

Gualtieri, Antonio R. Search for Meaning: Exploring Religions of the World.

Guernica Editions: 1991, Canada. 62.

Kapunan, Sal. Everyone is an Artist: Making Yourself the Artwork. iUniverse:

2003, Lincoln. 6.

King, James. Under Foreign Eyes: Western Cinematic Adaptions of Postwar

Japan. Zero Books: 2012, Alresford. 141.

Poole, Ralph J. Moonlight Blossoms and White Chrysanthemums.

Melodrama! The Mode of Excess from Early America to Hollywood. Eds. Ruth

Mayer, Frank Kelleter, Barbara Krah. Heidelberg: Universittsverlag Winter,

2007. 167ff.

Ruth, Maria P.P. Women. Handbook of Asian American Psychology. Lee. C.

Lee, Nolan W.S. Zane. California: Sage Publications, 1998. 213.

Said, Edward. Orientalism. The Post-Colonial Studies Reader. Eds. Bill

Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths, Helen Tiffin. London: Routledge, 1995. 87 ff.

Strinati, Dominic. An Introduction to Studying Popular Culture. Routledge:

London, 2000. 34.

Sun, Wei. Minority Invisibility. An Asian American Experience. UP: Lanham,

2007. 20.

Tan, Ming. How to Attract Asian Women: An Asian Women Reveals it All.

Bridge Gap Books: New York, 2001. 33.

Teo, Hsu Ming. Orientalism and the Mass Market Romance Novels in the

Twentieth Century. Edward Said. The Legacy of a Public Intellectual. Eds.

Ned Curthoys, Debjani Ganguly. Melbourne: University Press, 2007. 242.

Trefflich, Cornelia. Edward Saids Orientalism: A Reflection. GRIN Verlag:

Norderstedt, 2007. 6.

Ujiie, Iro. Inked Justice: Freelance Samurai. Privateer Book Publishing: Boise,

2007. 51.

11

Varisco, Daniel Martin. Reading Orientalism: Said and the Unsaid.

Washington Press: Seattle, 2007. 160.

Yegenoglu, Meyda. Colonial Fantasies: Towards a feminist reading of

Orientalism. Cambridge University Press: Melbourne, 2008. 15.

Вам также может понравиться

- Cruise Ship Song List (2021)Документ7 страницCruise Ship Song List (2021)EntonyKarapetyan100% (4)

- Alan Watts How To MeditateДокумент8 страницAlan Watts How To MeditateAlexAxl100% (5)

- PictureOfDorianGray TM 956Документ16 страницPictureOfDorianGray TM 956pequen30Оценок пока нет

- Embodied Resistance NodrmДокумент289 страницEmbodied Resistance NodrmAna Maria Ortiz100% (1)

- Nostalgia and Autobiography:the Past in The Present.Документ23 страницыNostalgia and Autobiography:the Past in The Present.dreamer44Оценок пока нет

- Von Post Humification ScaleДокумент1 страницаVon Post Humification ScaleGru Et100% (1)

- Screen - Volume 15 Issue 4Документ99 страницScreen - Volume 15 Issue 4Krishn KrОценок пока нет

- Introduction To Male Gaze in Visual ArtДокумент20 страницIntroduction To Male Gaze in Visual ArtAvrati BhatnagarОценок пока нет

- Animals in Irving and MurakamiДокумент136 страницAnimals in Irving and MurakamiCristiana GrecuОценок пока нет

- Womanliness As A MasqueradeДокумент10 страницWomanliness As A MasqueradeΓγγγηξ ΦφγηξξβОценок пока нет

- Humanism, Gynocentrism and Feminist PoliticsДокумент11 страницHumanism, Gynocentrism and Feminist Politics起铭陈Оценок пока нет

- The Gospel of HeavenДокумент8 страницThe Gospel of HeavenThomas Francisco Pelgero100% (3)

- Lista EurodanceДокумент8 страницLista EurodanceNelson van RoinujОценок пока нет

- Barthes Er L ImageДокумент12 страницBarthes Er L ImageduquebuitreОценок пока нет

- University of Wisconsin PressДокумент15 страницUniversity of Wisconsin PressworkmaccОценок пока нет

- NYC Subway MapДокумент1 страницаNYC Subway Mapgregoryo59100% (1)

- Queering Contact Improvisation PDFДокумент5 страницQueering Contact Improvisation PDFAna GarbuioОценок пока нет

- Mother-Daughter Relationships From Reader's Guide To Women's StudiesДокумент2 страницыMother-Daughter Relationships From Reader's Guide To Women's StudiesFaraiОценок пока нет

- Brute ReviewДокумент4 страницыBrute Reviewrose beardmore100% (1)

- Saving Humanity Through Gender Reversal - A Feminist Interpretation of Shinseiki Evangelion - Genevieve PettyДокумент5 страницSaving Humanity Through Gender Reversal - A Feminist Interpretation of Shinseiki Evangelion - Genevieve Pettyleroi77100% (1)

- IT S LIT E21 Drs Keisha Blain and Ibram X Kendi LДокумент8 страницIT S LIT E21 Drs Keisha Blain and Ibram X Kendi LGMG EditorialОценок пока нет

- Henri-Jean Martin - The History and Power of Writing-University of Chicago Press (1995)Документ617 страницHenri-Jean Martin - The History and Power of Writing-University of Chicago Press (1995)inayat1Оценок пока нет

- Sophia Volume 50 Issue 4 2011 (Doi 10.1007 - S11841-011-0276-Y) Matthew Lamb - Philosophy As A Way of Life - Albert Camus and Pierre Hadot PDFДокумент16 страницSophia Volume 50 Issue 4 2011 (Doi 10.1007 - S11841-011-0276-Y) Matthew Lamb - Philosophy As A Way of Life - Albert Camus and Pierre Hadot PDFSepehr DanesharaОценок пока нет

- English 275: You Are Who You Eat: Cannibalistic Thinking in Literature Colleen E. KennedyДокумент8 страницEnglish 275: You Are Who You Eat: Cannibalistic Thinking in Literature Colleen E. KennedyColleen KennedyОценок пока нет

- LJPДокумент1 страницаLJPAdityaОценок пока нет

- (Cultural Critique) Cesare Casarino, Andrea Righi - Another Mother - Diotima and The Symbolic Order of Italian Feminism-University of Minnesota Press (2018)Документ344 страницы(Cultural Critique) Cesare Casarino, Andrea Righi - Another Mother - Diotima and The Symbolic Order of Italian Feminism-University of Minnesota Press (2018)Alaide Lucero100% (2)

- Littlewood - Mental Illness As Ritual TheatreДокумент13 страницLittlewood - Mental Illness As Ritual TheatreMarlene TavaresОценок пока нет

- Somatosphere - Anti-Witch Book ForumДокумент15 страницSomatosphere - Anti-Witch Book Forumadmin1666Оценок пока нет

- MILNER, J-C. The Tell-Tale ConstellationsДокумент8 страницMILNER, J-C. The Tell-Tale ConstellationsDavidОценок пока нет

- Case Falling in LoveДокумент1 страницаCase Falling in Lovekaushik_ranjan_2Оценок пока нет

- An Interview With Marguerite Duras - Germaine Brée, Marguerite Duras and Cyril DohertyДокумент23 страницыAn Interview With Marguerite Duras - Germaine Brée, Marguerite Duras and Cyril DohertyPantuflaОценок пока нет

- Myth of Everyday LifeДокумент22 страницыMyth of Everyday LifeAna-Marija SenfnerОценок пока нет

- Notes Epistemologies of The SouthДокумент7 страницNotes Epistemologies of The SouthNinniKarjalainenОценок пока нет

- UntitledДокумент92 страницыUntitledManon BatteuxОценок пока нет

- Ben Okri - in ArcadiaДокумент16 страницBen Okri - in ArcadiaMemento Vivere0% (1)

- Mad Love ProphecyДокумент17 страницMad Love ProphecyCrina PoenariuОценок пока нет

- Komatsu Kazuhiko - Bstudies On Izanagi-Ryū: A Historical Survey of Izanagi-Ryū Tayū (Hayashi Review)Документ4 страницыKomatsu Kazuhiko - Bstudies On Izanagi-Ryū: A Historical Survey of Izanagi-Ryū Tayū (Hayashi Review)a308Оценок пока нет

- BK Harp 011475Документ91 страницаBK Harp 011475GaoMing100% (1)

- The Homology of Music and Myth - Views of Lévi-Strauss On Musical Structure (Pandora Hopkins)Документ16 страницThe Homology of Music and Myth - Views of Lévi-Strauss On Musical Structure (Pandora Hopkins)thomas.patteson6837100% (1)

- (Gender in A Global - Local World) Jacqueline Leckie-Development in An Insecure and Gendered World - The Relevance of The Millennium Goals-Ashgate (2009) PDFДокумент267 страниц(Gender in A Global - Local World) Jacqueline Leckie-Development in An Insecure and Gendered World - The Relevance of The Millennium Goals-Ashgate (2009) PDFDamla YazarОценок пока нет

- Maxime Cervulle - French Homonormativity and The Commodification of The Arab BodyДокумент11 страницMaxime Cervulle - French Homonormativity and The Commodification of The Arab BodyRafael Alarcón VidalОценок пока нет

- Art Critique - Memoirs of A Geisha 2Документ3 страницыArt Critique - Memoirs of A Geisha 2api-507084438Оценок пока нет

- Gothic Monsters MasculinityДокумент15 страницGothic Monsters MasculinityHéctor Montes AlonsoОценок пока нет

- Lauretis - Aesthetic and Feminist Theory PDFДокумент11 страницLauretis - Aesthetic and Feminist Theory PDFJeremy DavisОценок пока нет

- Soma: An Anarchist Play Therapy: G. Ogo, Drica Dejerk Fall-Winter 2008Документ8 страницSoma: An Anarchist Play Therapy: G. Ogo, Drica Dejerk Fall-Winter 2008moha1rsamОценок пока нет

- Back to Methuselah: A Metabiological PentateuchОт EverandBack to Methuselah: A Metabiological PentateuchРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (3)

- Profiles of Women Past & Present: Mosaic - Nine Women in ScienceОт EverandProfiles of Women Past & Present: Mosaic - Nine Women in ScienceОценок пока нет

- (Bryson) Queer Pedagogy PDFДокумент24 страницы(Bryson) Queer Pedagogy PDFdicionariobrasilОценок пока нет

- Sarah Keller. Anxious Cinephilia Pleasure and Peril at The Movies. Columbia University Press. 2020Документ318 страницSarah Keller. Anxious Cinephilia Pleasure and Peril at The Movies. Columbia University Press. 2020程昕100% (1)

- Womanliness As A Masquerade Joan+RivièreДокумент11 страницWomanliness As A Masquerade Joan+RivièreGabiCaviedes100% (1)

- Epictetus On Love ArticleДокумент17 страницEpictetus On Love ArticlempcantavozОценок пока нет

- Memoirs of A Geisha Film&Novel ComparativeДокумент5 страницMemoirs of A Geisha Film&Novel Comparativemaisuri123100% (1)

- Cixous CarrollДокумент22 страницыCixous CarrollLucia NigroОценок пока нет

- (Benjamin J. Abraham - Digital Games After Climate Change-Palgrave Macmillan (2022)Документ263 страницы(Benjamin J. Abraham - Digital Games After Climate Change-Palgrave Macmillan (2022)Krishna Bahadur BohoraОценок пока нет

- ZECCHI 05. All About Mothers. Pronatalist Discourses in Contemporary Spanish CinemaДокумент20 страницZECCHI 05. All About Mothers. Pronatalist Discourses in Contemporary Spanish CinemamonicasumoyОценок пока нет

- An Interview With Agnes Heller: "The Essence Is Good But All The Appearace Is Evil"Документ53 страницыAn Interview With Agnes Heller: "The Essence Is Good But All The Appearace Is Evil"hobiosОценок пока нет

- Irigaray - A Future Horizon For ArtДокумент14 страницIrigaray - A Future Horizon For ArtRachel ZolfОценок пока нет

- Adrian Johnston and Catherine MalabouДокумент13 страницAdrian Johnston and Catherine MalabouzizekОценок пока нет

- Theatre and Encounter: The Psychology of the Dramatic RelationshipОт EverandTheatre and Encounter: The Psychology of the Dramatic RelationshipОценок пока нет

- Howe Essay Documentary Film Marker PDFДокумент27 страницHowe Essay Documentary Film Marker PDFCarolina SourdisОценок пока нет

- Listen To Me MarlonДокумент17 страницListen To Me MarloncecunnОценок пока нет

- Intermedia BrederДокумент13 страницIntermedia BrederAndré RodriguesОценок пока нет

- When Lips Speak Together IrigarayДокумент8 страницWhen Lips Speak Together IrigarayJonathan KormanОценок пока нет

- Kanchan 2013 The Odia MagazineДокумент72 страницыKanchan 2013 The Odia MagazineBiswajit MohapatraОценок пока нет

- ListeningДокумент31 страницаListeningAlesandro vieriОценок пока нет

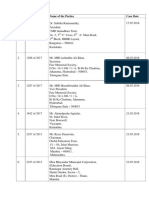

- S.No. Case No. Name of The Parties Case Date: RD TH NDДокумент4 страницыS.No. Case No. Name of The Parties Case Date: RD TH NDAasim Ahmed ShaikhОценок пока нет

- one-day-dLL COT 2nd QuarterДокумент5 страницone-day-dLL COT 2nd Quarterwilbert giuseppe de guzmanОценок пока нет

- Spiritual Authority and Spiritual Power by RevДокумент12 страницSpiritual Authority and Spiritual Power by RevAndy EbhotaОценок пока нет

- Always Looking Up - The Adventures of An Incurable Optimist - Michael J. Fox-VinyДокумент75 страницAlways Looking Up - The Adventures of An Incurable Optimist - Michael J. Fox-VinyFatima RafiqueОценок пока нет

- 201434662Документ88 страниц201434662The Myanmar TimesОценок пока нет

- Local ShoppingДокумент2 страницыLocal ShoppingMariangely RamosОценок пока нет

- Literature and Poetry ArtДокумент29 страницLiterature and Poetry ArtAspiringInstruc2rОценок пока нет

- Unit 4 TestДокумент4 страницыUnit 4 TestJuanJesusOcañaAponteОценок пока нет

- De Lauretis, Teresa. Guerrilla in The Midst. Women's CinemaДокумент20 страницDe Lauretis, Teresa. Guerrilla in The Midst. Women's CinemaKateryna SorokaОценок пока нет

- Project Camelot David Wilcock (The Road To Ascension) 2007 Transcript - Part 1Документ19 страницProject Camelot David Wilcock (The Road To Ascension) 2007 Transcript - Part 1phasevmeОценок пока нет

- Annotated Bibliography For House Made of DawnДокумент6 страницAnnotated Bibliography For House Made of DawnRam GoliОценок пока нет

- Roland U20 Keyboard ManualpdfДокумент2 страницыRoland U20 Keyboard Manualpdfvandat1Оценок пока нет

- The Three Important Facts Which Influence The Literature of Victorian AgeДокумент6 страницThe Three Important Facts Which Influence The Literature of Victorian Agerisob khanОценок пока нет

- Al-Ghazalis Theory of Mstical Cognition and Its Avicennian FoundationДокумент4 страницыAl-Ghazalis Theory of Mstical Cognition and Its Avicennian FoundationkhairaniОценок пока нет

- Eschatology - Gog and Magog - Ezekiel 38-39 (Moscala)Документ35 страницEschatology - Gog and Magog - Ezekiel 38-39 (Moscala)Rudika Puskas100% (1)

- DUNGEONS ExtendidoДокумент112 страницDUNGEONS ExtendidoEdgardo De La CruzОценок пока нет

- Buehler Summet, Sample Prep and AnalysisДокумент136 страницBuehler Summet, Sample Prep and AnalysisSebastian RiañoОценок пока нет

- Consequences and The Difference Between KarmaДокумент1 страницаConsequences and The Difference Between Karmacosmicwitch93Оценок пока нет

- Character Study OperaДокумент2 страницыCharacter Study Operaapi-254073933Оценок пока нет

- Dept Student Name List 2017-2018Документ6 страницDept Student Name List 2017-2018Subbu NatarajanОценок пока нет

- The Quran Package: Seiied Mohammad Javad Razavian 2018/12/31 Ver 1.5Документ17 страницThe Quran Package: Seiied Mohammad Javad Razavian 2018/12/31 Ver 1.5suprianto basukiОценок пока нет

- Burke Cursing ApostlesДокумент25 страницBurke Cursing ApostlesFolarin AyodejiОценок пока нет