Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

A Comparative Analysis of Private Pensions

Загружено:

Masa Claudiu MugurelИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

A Comparative Analysis of Private Pensions

Загружено:

Masa Claudiu MugurelАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

A comparative analysis

of mandated private pension

arrangements

Mark Hyde and John Dixon

School of Law and Social Science, University of Plymouth, Plymouth, UK

Abstract

Purpose According to one inuential set of arguments, the privatization of public pensions has

been informed by neoliberalism, and has thus been an integral element of a broader program of welfare

retrenchment, which is inconsistent with social cohesion. The paper aims to take issue with this

negative characterization of pensions privatization.

Design/methodology/approach The argument is illustrated by a cross-national comparative

analysis of the principal design features of 32 mandated private pension arrangements.

Findings The market orientation of mandated private pension arrangements is generally

ambivalent. Whilst the architects of these arrangements have embraced market principles, they have

also accepted the principle of collective responsibility for retirement futures.

Research limitations/implications While design is an important indicator of the nature of

pension schemes, it does not translate automatically into retirement outcomes.

Practical implications Collective responsibility for retirement may be pursued through

distinctive forms of privatization.

Originality/value In contrast to the central argument of much of the literature, the privatization of

public pensions has not universally or unambiguously been informed by the tenets of neoliberal

political economy.

Keywords Pensions, Privatization, Responsibilities, Design, Social policy

Paper type Research paper

Although neo-classical economics has undoubtedly driven the global privatization reform

agenda, it does not provide an adequate framework for the reform of retirement-income

protection . . . when confronted with the challenge of income maintenance for those in

retirement, policy makers must necessarily tackle strategically important, values laden

questions. This requires them to engage in policy discourses that are informed by competing

welfare ideologies (Dixon and Hyde, 2003, p. 1).

Introduction

According to one inuential set of arguments, the privatization of pensions is an

integral element of a broader program of welfare retrenchment, informed by

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at

www.emeraldinsight.com/0306-8293.htm

The authors acknowledge the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada

(SSHRCC) for a grant to nance their empirical investigation of extant mandated private pension

schemes; the Social Protection Advisory Service of the World Bank and the International Social

Security Association, who provided us with assistance in acquiring comprehensive pension

program legislation and other documentation; and ofcials of the Association Generale des

Institutions de Retraite des Cadres (AGIRC) and the Association pour le Regime de Retraite

Complementaire des Salaries (ARRCO), who agreed to be interviewed regarding the design and

operation of the French complementary regimes.

Analysis of

private pension

arrangements

49

International Journal of Social

Economics

Vol. 35 No. 1/2, 2008

pp. 49-62

qEmerald Group Publishing Limited

0306-8293

DOI 10.1108/03068290810843837

neoliberalism, which has been designed to divest the state of its responsibility for

securing public interest objectives with regard to retirement futures. This diminution

of collective responsibility for social security is unacceptable, we are told, because it

will intensify retiree poverty in years to come (Martin, 1993; Klein and Millar, 1995;

Bonoli et al., 2000; Trampusch, 2007).

Building on a conceptual framework that was originally developed in an earlier

volume of this journal (Dixon and Hyde, 2003), this paper takes issue with this negative

characterization of pensions privatization. First, we describe in some detail the

principal arguments of those who maintain that pension privatization has converged,

globally, around the core assumptions and values of the neoliberal welfare reform

model. This usefully contextualizes our own contribution. Second, we assess

empirically the extent to which the architects of 32 mandated private pension

arrangements[1] have engaged with market principles. The ndings of this assessment

are clear: a strong-market orientation, as expounded by neoliberalism, is not a

universal or unambiguous feature of pensions privatization. This might suggest that

privatization can be consistent with the principle of collective responsibility for

retirement futures.

Neoliberal convergence?

The shift from public to private (non-state) pension administration, which is inherent in

recent privatization reforms, has suggested to a number of observers that pension

policy has converged around the precepts of the neoliberal welfare reform model

(Martin, 1993; Klein and Millar, 1995; Bonoli et al., 2000; Pinera, 2001; Rowlingson,

2002; Trampusch, 2007).This argument rests on two assumptions.

The rst is that pension privatization has been informed, ideologically, by the

anti-collectivist values of neoliberal political economy (Bonoli et al., 2000; Pinera, 2001;

Borzutsky, 2002). For Martin (1993, p. 6), the privatization of welfare, including pension

provision, has been guided by a global neoliberal alliance of:

. . . economists . . . the big banks and management consultancies; the World Bank and the

IMF; regional nancial institutions . . . Their broadly shared outlook is that the free market

knows best and the private sector does best.

However, this belief is not conned to those on the left of the ideological spectrum.

Jose Pinera, the Minister responsible for the privatization of the Chilean pension system

in 1981, describes how the precepts and principles of neoliberalism provided our

guiding vision: indeed, the reform was introduced as part of a coherent set of radical

free market reforms, creating a political and cultural atmosphere more consistent

with free markets and a free society (Pinera, 2001, pp. 3-4). But what about those

countries where pension provision has been privatized by governments of the

centre-left? This does not, we are told, contradict the notion that privatization has been

informed by neoliberal political economy. The problem with the rhetoric of

neoliberalism in its pure form is its naked endorsement of intensied social

inequalities, which creates political barriers to the implementation of market reforms.

The solution, we are told, has been to seal the victory of the market by preserving

the placebo of a compassionate public authority, but, at the same time, extolling the

compatibility of competition with solidarity. Pension privatization is now carefully

surrounded with subsidiary concessions and softer rhetoric in order to kill off

IJSE

35,1/2

50

opposition to neoliberal hegemony completely (Anderson, 2000, p. 11). In this view,

centre-left values are merely an ideological shell for neoliberalism, which is now

dominant in the assumptive worlds of policy-makers (Bonoli et al., 2000, p. 2).

The second assumption underpinning the neoliberal convergence thesis is that

pension privatization has been a part of a broader exercise in welfare retrenchment that

has entailed a substantial and unambiguous shift away from collective to

individual responsibility (Klein and Millar, 1995; Rowlingson, 2002). Collective

responsibility may generally be dened as the assumption of obligations by a public

authority to pursue ends that, arguably, cannot be achieved through private action

alone. In terms of pension planning and provision, collective responsibility has been

justied in terms of several distinctive normative principles, including need,

citizenship and social justice (Hyde et al., 2007). This requires a:

. . . society working together for the good of the whole in a spirit which combines both

altruism and self-interest. Individuals are taking collective responsibility for their welfare

rather than individual responsibility (Rowlingson, 2002, p. 625).

Collective responsibility for social security has also been justied in terms of a

particular assumption about human behavior when people are confronted with

long-term risk and needs contingencies: the maintenance of coherent beliefs and

preferences is too demanding a task for limited minds (Taylor-Gooby, 1998, p. 13).

This diminished capacity for rational decision making is perhaps more evident in the

area of retirement planning, where the connection between choices and outcomes may

be obscured by the passage of time. A recent study of public attitudes regarding

long-term saving, for example, found convincing evidence of deeply entrenched

myopia, including a limited capacity to conceptualize and prepare for the future

(Rowlingson, 2002). Typically, collective responsibility for the provision of

retirement-benets has taken the form of pay-as-you-go (PAYG) nanced social

insurance and tax nanced social assistance programs.

In contrast, individual responsibility may be dened broadly as self-provisioning,

or what Klein and Millar (1995) describe as DIY [do-it-yourself] welfare, a notion that

rests on two sets of assumptions. The rst is that individuals do have the capacity

to act competently in the marketplace, which means that they are able to make suitable

arrangements for their retirement (Friedman, 1999). This encompasses assumptions

about: the motivation to be self-reliant; the cognitive capacity to consider

retirement-income protection needs over the course of the life-cycle; the internal

resources that are necessary to acquire relevant information to guide choices in pension

markets; and the nancial capacity to purchase retirement-income protection products.

If we are to rely predominantly on individual responsibility to meet retirement-income

needs, these capacities must be widely distributed (Rowlingson, 2002). The second set

of assumptions concerns the capacity of the market to respond, effectively, to the

decisions of purchasers (Friedman, 1999). Essentially, it is argued that self-regulated

markets will, through the liberalization of market entry, maximize competition. By

extension, this will promote choice and provide the corporate sector with the incentives

necessary to be responsive to buyer preferences. Individual self-reliance will translate,

axiomatically, but perhaps not immediately, into satisfactory market-led pension

arrangements (Shapiro, 1998).

Analysis of

private pension

arrangements

51

We are not concerned, here, with the veracity of these arguments, but with the

sweeping assumption that pension privatization has, unambiguously and universally,

entailed a shift away from collective to individual responsibility.

Is privatization market oriented?

Reecting this concern, we turn to our quantitative assessment of the degree to which

the design of mandated private pension arrangements is market orientated. Central to

our approach is the distinction between collective and market orientations.

A collective orientation is indicated by a high degree of collective responsibility for

retirement futures, mediated through statutory rights and obligations. A market

orientation, in contrast, entails a discernable reliance on market principles, such as

freedom of choice, voluntary action and private pension industry self-regulation. Each

national mandated private pension arrangement is judged in terms of eight dimensions

of provision, and according to a four-point scale, ranging from a strong-collective

orientation (score 1), through a weak-collective orientation (score 2) and a weak-market

orientation (score 3), to a strong-market orientation (score 4). These dimensions

were operationalized exclusively in terms of social security design features, thereby

focusing on policy inputs, reecting the aims and values of the architects of extant

mandated private pension schemes, rather than policy outcomes or impacts. Our focus

is entirely appropriate at the present time since a majority of the schemes under

consideration are of recent origin. Outcomes will of course become a more salient issue

when those who are afliated to mandated private pension schemes begin to retire.

The dimensions of provision that were used to establish the degree of market

orientation were determined, and operationalized, by circulating an extensive list of

social security design features to members of an international panel of acknowledged

experts on private pensions. Agreement was reached on the following eight

dimensions, and their specic mode of operationalization: the social security

objective[2] guiding a particular reform, the type of scheme[3] introduced, the type of

provision for the uncovered[4], the coverage[5] of the mandated private arrangement,

the nancing[6] arrangements adopted, eligibility[7] conditions, the form of benets[8]

provided, and the governance[9] arrangements for ensuring that mandated

private provision complies with the requirements of the public interest. It should be

acknowledged, of course, that while design is the most important indicator of the

nature of pension arrangements, retirement outcomes may be inuenced by a range of

contingencies (Hyde et al., 2007).

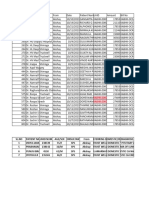

The market orientation of extant mandated private pension schemes

Table I presents our ndings. On an aggregate basis, we judge the degree of market

orientation, as a percentage of the maximum possible score, at 62 percent, which,

across the eight dimensions, ranges from 46 percent for the coverage dimension to

77 percent for type of scheme dimension. A strong-market orientation score was

achieved on at least one dimension in 21 countries (65 percent of countries), while

a strong-collective orientation score was achieved on at least one dimension in

22 countries (69 percent of countries). Those countries achieving a market-orientation

score in excess of 62 percent were located predominantly in Latin America

(ten countries) and Central and Eastern Europe (six countries), with Hong Kong,

Papua New Guinea and Sweden being the other countries. Those achieving a

IJSE

35,1/2

52

M

a

r

k

e

t

r

a

n

k

i

n

g

M

a

r

k

e

t

s

c

o

r

e

(

p

e

r

c

e

n

t

)

C

o

u

n

t

r

y

S

o

c

i

a

l

s

e

c

u

r

i

t

y

o

b

j

e

c

t

i

v

e

T

y

p

e

o

f

s

c

h

e

m

e

P

r

o

v

i

s

i

o

n

f

o

r

t

h

e

u

n

c

o

v

e

r

e

d

C

o

v

e

r

a

g

e

F

i

n

a

n

c

i

n

g

E

l

i

g

i

b

i

l

i

t

y

B

e

n

e

t

s

G

o

v

e

r

n

a

n

c

e

1

8

4

P

a

p

u

a

N

e

w

G

u

i

n

e

a

4

3

4

3

2

3

4

4

2

7

8

U

r

u

g

u

a

y

4

4

2

2

3

2

4

4

3

7

5

B

o

l

i

v

i

a

4

4

3

2

3

2

2

4

3

7

5

H

o

n

g

K

o

n

g

2

3

3

4

2

2

4

4

3

7

5

K

a

z

a

k

h

s

t

a

n

4

4

3

2

3

1

4

3

3

7

5

L

a

t

v

i

a

2

4

2

2

3

3

4

4

7

7

2

A

r

g

e

n

t

i

n

a

3

4

2

2

3

1

4

4

7

7

2

C

h

i

l

e

4

4

2

2

3

1

4

3

7

7

2

E

c

u

a

d

o

r

3

4

2

2

3

1

4

4

7

7

2

M

a

c

e

d

o

n

i

a

2

4

2

2

3

3

4

3

1

1

6

9

C

o

l

u

m

b

i

a

3

3

2

2

2

2

4

4

1

1

6

9

E

l

S

a

l

v

a

d

o

r

4

3

2

2

2

1

4

4

1

1

6

9

P

e

r

u

3

4

2

2

3

1

3

4

1

4

6

6

B

u

l

g

a

r

i

a

2

3

2

2

2

3

4

3

1

4

6

6

C

o

s

t

a

R

i

c

a

2

3

3

2

2

3

3

3

1

4

6

6

S

w

e

d

e

n

2

3

3

1

1

4

3

4

1

4

6

6

U

k

r

a

i

n

e

2

3

3

1

1

3

4

4

1

8

6

3

M

e

x

i

c

o

4

3

2

1

1

1

4

4

1

8

6

3

E

s

t

o

n

i

a

2

3

2

1

1

3

4

4

1

8

6

3

C

r

o

a

t

i

a

2

4

2

2

3

1

3

3

2

1

5

9

D

o

m

i

n

i

c

a

n

R

e

p

u

b

l

i

c

4

3

2

1

1

1

4

3

2

1

5

9

H

u

n

g

a

r

y

2

4

2

2

2

3

1

3

2

1

5

3

L

i

e

c

h

t

e

n

s

t

e

i

n

2

2

3

3

2

1

1

3

2

1

5

3

P

o

l

a

n

d

2

3

2

2

3

1

3

1

2

1

5

3

S

w

i

t

z

e

r

l

a

n

d

2

2

3

3

2

3

1

1

2

6

5

0

S

o

u

t

h

K

o

r

e

a

2

1

3

1

1

3

1

4

2

6

5

0

U

n

i

t

e

d

K

i

n

g

d

o

m

3

3

3

2

2

1

1

1

2

8

4

7

S

l

o

v

a

k

i

a

2

2

3

1

1

3

2

1

2

9

4

4

F

i

n

l

a

n

d

2

2

3

1

1

2

1

2

2

9

4

4

F

r

a

n

c

e

2

3

3

1

1

1

2

1

2

9

4

4

I

c

e

l

a

n

d

2

2

1

2

2

2

1

2

3

2

3

8

A

u

s

t

r

a

l

i

a

2

2

3

1

1

1

1

1

N

o

t

e

s

:

1

S

t

r

o

n

g

c

o

l

l

e

c

t

i

v

e

o

r

i

e

n

t

a

t

i

o

n

;

2

w

e

a

k

c

o

l

l

e

c

t

i

v

e

o

r

i

e

n

t

a

t

i

o

n

;

3

w

e

a

k

-

m

a

r

k

e

t

o

r

i

e

n

t

a

t

i

o

n

;

4

s

t

r

o

n

g

-

m

a

r

k

e

t

o

r

i

e

n

t

a

t

i

o

n

Table I.

The degree of market

orientation of mandated

private pension

arrangements

Analysis of

private pension

arrangements

53

market-orientation score below 62 percent were located predominantly in Western

Europe (six countries), as might be expected, and Central and Eastern Europe (four

countries), with Australia, the Dominican Republic and South Korea being the other

countries.

More specically, our ndings give rise to two propositions. First, the market

orientation of the design of extant mandated private pension schemes is generally

ambivalent. Those dimensions of provision that achieved the strongest

market-orientation scores were as follows:

.

Type of scheme (average score 3.09, 77 percent) Ten countries demonstrated a

strong-market orientation, while only South Korea demonstrated a

strong-collective orientation. This should not be surprising given the

preponderance of dened-contribution provision (88 percent of schemes).

.

Governance (3.03, 76 percent) About 14 countries demonstrated a strong-market

orientation, while only six countries demonstrated a strong-collective orientation.

The architects of mandated private pension schemes have generally taken the

view that once approved, the scheme operators should be largely self-regulated,

subject to the requirement that they conduct their affairs in a responsible and

prudent manner.

.

Benets (2.91, 73 percent) About 15 countries demonstrated a strong-market

orientation, while eight demonstrated a strong-collective orientation. Again, this

is not surprising, given that the most common forms of benets are annuities

(93 percent of schemes), programmed withdrawals (64 percent of schemes), or

lump sum payments (64 percent of schemes).

.

Social security objective (2.63, 66 percent) Eight countries demonstrated a

strong-market orientation, but no country demonstrated a strong-collective

orientation. Indeed, a large minority of mandated private pension schemes have

either replaced a public program (25 percent of schemes), or provide an

alternative to a publicly administered program (16 percent of schemes).

When considered in isolation, these ndings might suggest that there is a strong

degree of correspondence between the design features of mandated private pension

schemes and the tenets of neoliberalism (Rowlingson, 2002; Ginn, 2003). However, four

dimensions achieved relatively low-market orientation scores:

(1) Coverage (1.84, 46 percent) Only Hong Kong demonstrated a strong-market

orientation, while ten countries demonstrated a strong-collective orientation.

This reects the prevalence of broad employment coverage, irrespective of

implications for administration costs and protability.

(2) Eligibility (1.97, 49 percent) Only Sweden demonstrated a strong-market

orientation, while 14 countries demonstrated a strong-collective orientation.

This is due primarily to the widespread practice of permitting access to accrued

benet entitlements prior to retirement (97 percent of schemes), and, to a lesser

extent, the adoption of early retirement provisions (63 percent of schemes). It

also reects the refusal of the architects of many schemes to adopt deferred

retirement provisions.

(3) Finance (2.03, 51 percent) No country demonstrated a strong-market

orientation, while ten countries demonstrated a strong-collective orientation.

IJSE

35,1/2

54

This reects the willingness of most governments to demand that employers

contribute towards the cost of their employees retirement-benets (59 percent

of schemes) and/or to subsidize those benets themselves (75 percent of

schemes), particularly with respect to the most disadvantaged scheme

members.

(4) Provision for the uncovered (2.47, 62 percent) Only Papua New Guinea

demonstrated a strong-market orientation, while only Iceland demonstrated

a strong-collective orientation. This reects the co-existence of publicly

provided social insurance (50 percent of schemes) and social assistance

(75 percent of schemes) as alternative forms of retirement-income support for

those who are not covered by the mandated private arrangement.

Overall, then, it is clear that a strong-market orientation is not unambiguously reected

in the design of mandated private pension schemes. The view that pension

privatization is, comprehensively, informed by neoliberalism is at variance with our

empirical evidence.

Our second proposition is that the degree to which individual country-specic

mandated private pension arrangements are market orientated is variable. It is clear

that our ndings regarding the distinctive approaches adopted by the 32 countries do

not sit comfortably with recent assessments of the degree of collective responsibility

that is inherent in national pension systems. Esping-Andersens (1990, p. 53) seminal

appraisal, for example, places Australias retirement system at the foot of his

decommodication ladder, reecting a dominant historically entrenched legacy of

institutionalized liberalism. Yet as Esping-Andersen has acknowledged, Australia has

long had a relatively powerful labor movement, which has been reected, inter alia, in

the emphases of its mandated private pension arrangement, the Superannuation

Guarantee (introduced in 1992), on vertical income redistribution (through

employer-only contributions), broad employment focused coverage, and stakeholder

engagement, with extensive trade union involvement in the administration of

individual schemes. This places Australia at the bottom of our market-orientation

ladder, with an average market-orientation score of 1.5, and a weak or strong

collective-orientation score on seven dimensions of provision. According to our

assessment, and those that have been developed elsewhere (Mann, 2002), the design of

Australias mandated private pension arrangement is consistent with a high degree of

collective responsibility for retirement futures.

Similarly, the French pension system has been ranked highly on Esping-Andersens

decommodication scale, but it is not among his top performers, because it belongs to a

group of countries with a long historical legacy of conservative and/or Catholic

reformism which, although circumscribing the scope of market engagement, rely on

powerful social control devices such as a proven record of strong employment

attachment or strong familial obligations (Esping-Andersen, 1990, p. 53). Yet,

according to our assessment, France is second only to Australia in terms of the degree

to which the principle of collective responsibility has inuenced the design of its

mandated private pension arrangement, the complementary regimes (introduced in

1972), achieving an average market-orientation score of 1.75, and a weak or strong

collective-orientation score on six dimensions of provision: social security objective,

coverage, nancing, eligibility, benets and governance. This reects, inter alia,

Analysis of

private pension

arrangements

55

its emphasis on vertical income redistribution (through employer contributions), the

provision of a public rst-tier PAYG nanced social insurance program for those who

are covered by the second-tier mandated private arrangement, and a strong tradition of

stakeholder engagement through social partner administration, reecting the

widespread perception of social security as something which belongs to the world

of employment rather than to the state (Blackburn, 1999, p. 17; see also Conseil

dOrientation des Retraites, 2001; Hyde et al., 2003). Although the basic principles of

operation are approved by the state, the state does not interfere in the management and

nancing of complimentary pension schemes. This contrasts with Esping-Andersens

(1990, p. 51) characterization of the French approach as etatist.

According to one assessment (Segalman and Marsland, 1989, pp. x-xi), the Swiss

approach to social security, including retirement-income protection, provides an

exemplar of the neoliberal welfare reform model, towards which all Western European

retirement systems should be converging:

. . . the Swiss have managed to avoid overblown state welfare, and in consequence have

escaped the destructive penalties other Western countries have paid . . . The canker of welfare

dependency, which elsewhere threatens general prosperity and democratic freedom, is

absent.

Although the reliance on the private sector to administer the distinctive Swiss private

second-tier pension arrangement, the Beruiche Vorsorge (introduced in 1985), might

suggest a degree of correspondence with the tenets of neoliberalism, our assessment

suggests that its architects have embraced, substantially, the principle of collective

responsibility for retirement futures. This is reected in an average market-orientation

score of 2.1, and the attainment of a weak or strong collective-orientation score on ve

dimensions of provision: social security objective, type of scheme, nancing, benets

and governance. Undoubtedly, these achievements reect the absence of competition

employers must make provision for their own employees, who are thus denied the right

of exit; the engagement of stakeholders in the administration of individual plans,

through the requirement for each to appoint an audit committee, comprised equally of

employer and employee representatives; the imposition of intrusive statutory

regulation by the canton and federal supervisory authorities; substantial vertical

income redistribution, as evidenced by joint and equal employer and employee

contribution liabilities; and the provision of a highly redistributive, universal publicly

administered social insurance safety-net the Alters- and Hinterlassenenversicherung

(Tschudi, 1989; Suter and Mathey, 2002). Not surprisingly, the Swiss mandated private

pension arrangement occupies a position near the bottom of our market-orientation

ladder.

It has been suggested that recent economic and social transitions in the countries of

Central and Eastern Europe have been driven by the neoliberal reform model (Martin,

1993; Clarke, 2004). Reecting on the experiences of Hungary, Ferge (2004, p. 16)

acknowledges that public debate during the transition from communism to capitalism

was inuenced by a plurality of philosophical discourses, but each did not carry:

. . . the same weight. A slightly domesticated variant of the Neoliberal . . . orthodoxy seems to

occupy a dominant place. It is espoused also by political parties which on the basis of their

name belong to the political left. There is therefore practically no force which would tame

IJSE

35,1/2

56

the interests enforcing individualism in the name of economic growth. This happens at the

expense of solidaristic solutions, and breaks bonds within and between generations.

Taken at face value, this argument would suggest that Hungarys dened-contribution

mandated private pension arrangement, the Mandatory Private Pension Fund

(introduced in 1998), should be at a point near the bottom of any decommodication

scale, yet our assessment suggests that its design features endorse a signicant degree

of collective responsibility. This is reected in an average market-orientation score of

2.38, and the attainment of a weak or strong collective-orientation score on ve

dimensions of provision: social security objective, coverage, nancing, eligibility and

benets. This reects, inter alia, the exclusion of commercial-for-prot organizations

from the denition of those who may act as scheme operators, broad employment

focused coverage, and the provision of a public rst-tier PAYG nanced social

insurance program for those who are covered by the second-tier private arrangement

(Augusztinovics et al., 2002). It may also be noted that the dened-contribution

mandated private pension arrangements of Poland (introduced in 1999) and Slovenia

(introduced in 2001) achieved low-market orientation scores (2.13 and 1.89,

respectively). Clearly, all three countries have refused to accept the austere

market-driven reforms that, we are told, have been thrust on the countries of Central

and Eastern Europe.

In spite of a promising start, expressed in the strong degree of universality that

characterized the design of its retirement system, the UK is placed near the bottom of

Esping-Andersens (1990, p. 54) scale of decommodication, reecting its status as an

incomplete social democratic reform project: Labors record of post-war power was

too weak and interrupted to match the accomplishments of Scandinavia. This is

echoed by more recent assessments of the UK which have characterized its pension

system as neoliberal (Ginn, 2003). In contrast, the UKs mandated private pension

arrangement (which is comprised of two elements: dened-benet and

dened-contribution occupational pension schemes introduced in 1961 and

dened-contribution personal pension plans introduced in 1988), is situated near the

foot of our market-orientation ladder, reecting an average market-orientation score of

2.00, and the attainment of a weak or strong collective-orientation score on ve

dimensions of provision: coverage, nancing, eligibility, benets and governance. This

scoring is inuenced, inter alia, by the UKs emphasis on vertical income redistribution

(through employer contributions), broad employment focused coverage, the provision

of a public rst-tier PAYG nanced social insurance program, and extensive statutory

requirements regarding fees and commissions, investment, marketing, insolvency and

malfeasance (Ginn, 2003; Hyde et al., 2003). Clearly, the design of the UKs approach is

consistent with a signicant degree of collective responsibility for retirement futures.

This contrasts with the Swedish dened-contribution mandated private pension

arrangement, the Premium Pension (introduced in 1999), which is placed in the top half

of our market-orientation ladder, achieving an average market-orientation score of

2.63, and a weak or strong collective-orientation score on only 3D of provision: social

security objective, coverage and nancing (Government Ofces of Sweden, 2001). This

may surprise those who look back with nostalgia to the halcyon days of the Nordic

welfare state, but times and circumstances have indeed moved on.

At the other end of the spectrum is, of course, Chile, which some have regarded

as exemplifying the neoliberal approach to the privatization of pension provision

Analysis of

private pension

arrangements

57

(Pinera, 2001; Borzutsky, 2002). It is perhaps not surprising that Chiles dened-

contribution mandated private pension arrangement (introduced in 1981) occupies a

position near the top of our market-orientation ladder, reecting an average

market-orientation score of 2.88, and the attainment of a weak or strong market-

orientation score on ve dimensions of provision: social security objective, type of

scheme, nancing, benets and governance. Still, Chiles approach attains a weak or

strong collective-orientation score on three dimensions: provision for the uncovered,

coverage and eligibility, suggesting that it departs in signicant ways from the precepts

of neoliberalism.

Staying at this end of the spectrum, Hong Kongs approach to economic and social

policy has, heretofore, been characterized by a striking resemblance to the neoliberal

welfare reform model. Although a British colony until 1997, the Hong Kong

Government has been consistently hostile to social insurance programs of the kind

embraced in Western Europe. Now, as a special administrative region of the Peoples

Republic of China, Hong Kongs public authority has maintained its deeply entrenched

commitment to the laissez-faire market governance tradition: the Hong Kong

government is more committed to nineteenth century policies of allowing the free play

of market forces than is the case anywhere else in the world (Miners, 1995, p. 470).

This is clearly reected in the design of its dened-contribution mandated

private pension arrangement, the Mandatory Provident Fund (introduced in 2000),

which is located near the top of our market-orientation ladder, reecting an

average market-orientation score of 3.0, and the attainment of a weak or strong

market-orientation score on ve dimensions of provision: type of scheme, provision for

the uncovered, coverage, benets and governance. However, the Hong Kong

arrangement achieved a weak collective-orientation score on three dimensions, social

security objective, nancing and eligibility, reecting, inter alia, a degree of vertical

income redistribution, through the imposition of joint and equal employer and

employee contribution liabilities, and the maintenance of a State Compensation Fund,

should indemnity insurance be insufcient to accommodate benet losses arising from

fraud and malfeasance (Ngan et al., 2001). This clearly frustrates any attempt to

characterize Hong Kongs mandated private pension arrangement, unambiguously, as

a variant of the neoliberal welfare reform model.

Overall, then, our assessment of individual countries is clear. The degree to which

the design of extant mandated private pension arrangements is market oriented is

variable, with some demonstrating a relatively high degree of collective responsibility.

The argument that pension privatization has been informed by the market-oriented

principles of neoliberalism is not supported.

Conclusion

It follows from our analysis that the belief that privatization is inconsistent with

the principle of collective responsibility for needs satisfaction should not necessarily be

regarded as an insurmountable obstacle to such reform. Indeed, the case for some

acceptable public-interest-sensitive form of privatization is compelling. It is now

widely accepted that pension arrangements that rely predominantly on PAYG

nancing are, in the long term, unsustainable (Hyde et al., 2004). Publicly administered

pension arrangements are characterized by a strong degree of political risk, because

the contract between the state and the individual that is implicit in such provision may

IJSE

35,1/2

58

be changed arbitrarily, without notice, to the detriment of scheme members. It is clear,

of course, that those who are covered by publicly administered pension arrangements

are provided with few, if any, opportunities to engage in decision making regarding

scheme design and administration (Papadikis and Taylor Gooby, 1897). Reecting

these problems, a number of recent attitude surveys have suggested that public

pension arrangements have failed to sustain the trust of national publics (Hyde et al.,

2007). However, it is not clear that this may be addressed to the satisfaction of the

public by merely reforming state pension systems. According to recent attitude

surveys (Forma and Kangas, 1999), national publics increasingly endorse regulated

forms of private mandatory pension provision, where the risk of market failure is

minimized. This is a view that is shared by a growing number of national

governments, as we have seen, and by international agencies engaged in the reform of

social security. Instead of rejecting any and all forms of privatization, we believe that

pension analysts of all intellectual and ideological hues should engage with this

growing consensus, thereby developing arguments for public-interest-sensitive

privatization that accords with the collectivist social justice aims of an inclusive

society.

Notes

1. We are concerned with a specic form of privatization, where statutory measures have been

adopted to give a role to the private (non-state) sector in the administration of mandatory

pension schemes: specied individuals are required by law to join a private-pension plan,

operating within the framework of a state-mandated private-pension scheme, instead of, or

in addition to, participating in a publicly administered program. This approach, which may

encompass rst- and second-tier provision, may be distinguished from

privatization-by-stealth, where the retrenchment of publicly administered provision

creates a social protection gap, which encourages individuals to voluntarily afliate to a

third-tier private-pension scheme (Bonoli et al., 2000).

2. The degree of market orientation was judged as follows: a strong-collective orientation,

where there is only public provision of retirement-income protection (score 1);

a weak-collective orientation, where private provision compliments public provision

(score 2); a weak-market orientation, where private provision is an alternative to public

provision (score 3); and a strong-market orientation, where private provision replaces public

provision (score 4).

3. The degree of market orientation was judged as follows: a strong-collective orientation,

where there is only employer sponsored dened-benet schemes (score 1); a weak-collective

orientation, where there are occupational dened-contribution and/or dened-benet

schemes, or employer-nanced dened-contribution schemes (score 2); a weak-market

orientation, where there are personal and/or occupational dened-contribution and/or

dened-benet schemes (score 3); and a strong-market orientation, where there is only

personal dened-contribution provision (score 4).

4. The degree of market orientation was judged as follows: a strong-collective orientation,

where the uncovered are eligible for public social allowances (score 1); a weak-collective

orientation, where the uncovered are eligible for public social insurance (score 2); a

weak-market orientation, where the uncovered are only eligible for public social assistance

(score 3); and a strong-market orientation, where the uncovered are only able to make

voluntary provision in the absence of any public retirement-income protection provision

(score 4).

Analysis of

private pension

arrangements

59

5. The degree of market orientation was judged as follows: a strong-collective orientation,

where coverage extends beyond all employees and the self-employed to include other

population categories (score 1); a weak-collective orientation, where most employees and the

self-employed are covered, and where at least one-third of the following employee categories

are exempted temporary employees, casual employees, part-time employees, guest

employees, limited contract employees, contract employees, domestic servants, employees

over the retirement-age, and low-income employees (score 2); a weak-market orientation,

where specic categories of private-sector employers are exempt, where the self employed

only have voluntary access, and where at least one-third of the following employee

categories are exempted temporary employees, casual employees, part-time employees,

guest employees, limited contract employees, contract employees, domestic servants,

employees over the retirement-age, and low-income employees (score 3); and a strong-market

orientation, where an income ceiling is imposed for benet or contribution purposes (score 4).

6. The degree of market orientation was judged as follows: a strong-collective orientation,

where benets are nanced by employers only, where joint employer-employee

contributions are centrally collected, where there is partial funding or PAYG nancing,

and where government subsidies apply (score 1); a weak-collective orientation, where

retirement-benets are fully funded by joint employer and employee contributions, or where

government subsidies apply (score 2); a weak-market orientation, where retirement-benets

are fully funded by employee contributions only, and where employee contributions are

centrally collected, or where government subsidies apply (score 3); and a strong-market

orientation, where retirement-benets are fully funded by employee contributions only,

where employee contributions are collected by pension funds, and where there are no

government subsidies available (score 4).

7. The degree of market orientation was judged as follows: a strong-collective orientation,

where eligibility conditions permit no deferred retirement, early retirement, gender

discrimination, or payment of pre-retirement-benets (score 1); a weak-collective orientation,

where eligibility conditions permit deferred and/or early retirement, and specify

pre-retirement withdrawal contingencies (for dened-contribution schemes) (score 2); a

weak-market orientation, where eligibility conditions specify pre-retirement withdrawal

contingencies (for dened-contribution schemes), and permit deferred retirement (score 3);

and a strong-market orientation, where eligibility conditions permit no early retirement, but

permit deferred retirement, and specify no pre-retirement withdrawal contingencies (for

dened-contribution schemes) (score 4).

8. The degree of market orientation was judged as follows: a strong-collective orientation,

where only earning-related pensions are paid (score 1); a weak-collective orientation, where

retirement-benets are determined by pension points, and where mandatory supplementary

benets are provided (score 2); a weak-market orientation, where retirement-benets take the

form of mandatory annuities or programmed withdrawals (score 3); and a strong-market

orientation, where retirement-benets are a matter of choice, or where combinations of

benet forms are permitted (score 4).

9. The degree of market orientation was judged as follows: a strong-collective orientation,

where a statutory monopoly has been granted to a non-prot organization, or where at least

one-third of following have been adopted competition measures, statutory rights, trust

accounts, a cap on commissions and charges, stakeholder representation on regulatory

agency boards, a public appeals process, government-sponsored pension funds, government

underwriting in the event of insolvency and mandatory investment requirements (score 1); a

weak-collective orientation, where at least one-third of following have been adopted

competition measures, statutory rights, employee or trade union representation on

regulatory agency boards, mandatory disclosure of commissions and charges, pension funds

sponsored by trade unions or social partners, industry, government or insurance guarantees

IJSE

35,1/2

60

in the event of insolvency and prohibited or restricted investments (score 2); a weak-market

orientation, where at least one-third of following have been adopted statutory rights,

industry representation on regulatory agency boards, pension fund guarantees in the event

of insolvency, prohibited or restricted investments (score 3); and a strong-market orientation,

where at least one-third of following have been adopted pension funds must have

acceptable nancial, corporate governance and ownership structures, no statutory rights are

granted, there are no mandatory investment requirements and there is no public appeals

process (score 4).

References

Anderson, P. (2000), Renewals, New Left Review, Vol. 11 No. 1, pp. 10-16.

Augusztinovics, M., Gal, R.I., Matits, A

., Mate, L., Simonovits, A. and Stahl, J. (2002), The

Hungarian pension system before and after the 1998 reform, in Fultz, E. (Ed.), Pension

Reform in Central and Eastern Europe, Volume 1, Restructuring with Privatisation: Case

Studies of Hungary and Poland, International Labour Ofce, Budapest, pp. 25-94.

Blackburn, R. (1999), The new collectivism: pension reform, grey capitalism and complex

socialism, New Left Review, Vol. 233, pp. 3-65.

Bonoli, G., George, V. and Taylor-Gooby, P. (2000), European Welfare States: Towards a Theory

of Retrenchment, Polity Press, Cambridge.

Borzutsky, S. (2002), Vital Connections: Politics, Social Security and Inequality in Chile, University

of Notre Dame Press, Notre Dame, IN.

Clarke, J. (2004), Changing Welfare, Changing Welfare States: New Directions in Social Policy,

Open University Press, Buckingham.

Conseil dOrientation des Retraites (2001), Retraites: Renouveler le Contrat Social entre les

Generations: Orientations de Debats, La Documentation Francaise, Paris.

Dixon, J. and Hyde, M. (2003), Public pension privatization: neo-classical economics, decision

risks and welfare ideology, International Journal of Social Economics, Vol. 30 No. 5,

pp. 633-50.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990), The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, Polity Press, Cambridge.

Ferge, Z. (2004), Is there a Public Philosophy in Central-Eastern Europe? Equity of Distribution

then and Now, ELTE Szocialpolitikai Intezet, Budapest.

Forma, P. and Kangas, O. (1999), Need, citizenship or merit: public opinion on pension policy in

Australia, Finland and Poland, in Svallfors, S. and Taylor-Gooby, P. (Eds), The End of the

Welfare State? Responses to State Retrenchment, Routledge, London, pp. 161-89.

Friedman, M. (1999), Speaking the Truth About Social Security Reform, Cato Brieng Paper

No. 46, The Cato Institute, Washington, DC.

Ginn, J. (2003), Gender, Pensions and the Lifecourse: How Pensions Need to Adapt to Changing

Family Forms, The Policy Press, Bristol.

Government Ofces of Sweden (2001), National Strategy Report on the Future of Pension

Systems, Government Ofces of Sweden, Stockholm.

Hyde, M., Dixon, J. and Drover, G. (2003), Welfare retrenchment or collective responsibility?

The privatization of public pensions in Western Europe, Social Policy and Society, Vol. 2

No. 3, pp. 189-98.

Hyde, M., Dixon, J. and Drover, G. (2004), Western European pensions privatization: a response

to Jay Ginn, Social Policy and Society, Vol. 3 No. 2, pp. 135-41.

Analysis of

private pension

arrangements

61

Hyde, M., Dixon, J. and Drover, G. (2007), Assessing the capacity of pension institutions to build

and sustain trust: a multidimensional conceptual framework, Journal of Social Policy,

Vol. 36 No. 3, pp. 457-76.

Klein, R. and Millar, J. (1995), Do-it-yourself social policy: searching for a new paradigm?, Social

Policy & Administration, Vol. 29 No. 4, pp. 303-16.

Mann, K. (2002), The Schlock and the new: risk, reexivity and retirement, paper presented at

the Social Policy Association Conference, University of Teeside, July 17.

Martin, B. (1993), In the Public Interest? Privatization and Public Sector Reform, Zed, London.

Miners, N. (1995), The Government and Politics of Hong Kong, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Ngan, R., Yip, N.M. and Wu, D. (2001), Poverty and social security, in Wong, L. and Gui, S.F.

(Eds), Shanghai and Hong Kong: A Tale of Two Cities, M.E. Sharpe, London, pp. 159-82.

Papadikis, E. and Taylor Gooby, P. (1897), Consumer attitudes and participation in state

welfare, Political Studies, Vol. XXXV No. 3, pp. 467-81.

Pinera, J. (2001), Liberating Workers: The World Pension Revolution, The Cato Institute,

Washington, DC.

Rowlingson, K. (2002), Private pension planning: the rhetoric of responsibility, the reality of

insecurity, Journal of Social Policy, Vol. 31 No. 4, pp. 623-42.

Segalman, R. and Marsland, D. (1989), Cradle to the Grave: Comparative Perspectives on the State

of Welfare, Macmillan, Basingstoke.

Shapiro, D. (1998), The Moral Case for Social Security Privatization, Social Security Privatization

No. 14, The Cato Institute, Washington, DC.

Suter, C. and Mathey, M.C. (2002), Wirksamkeit und Umverteilungseffekte staatlicher

Sozialleistungen, Bundesamt fur Statistik, Neuchatel.

Taylor-Gooby, P. (Ed.) (1998), Choice and Public Policy, Macmillan, Basingstoke.

Trampusch, C. (2007), Industrial relations as a source of solidarity in times of welfare state

retrenchment, Journal of Social Policy, Vol. 36 No. 2, pp. 197-216.

Tschudi, H.P. (1989), Entstehung und Entwicklung der schweizerischen Sozialversicherungen,

Zurich, Basel.

Corresponding author

Mark Hyde can be contacted at: mhyde@plymouth.ac.uk

IJSE

35,1/2

62

To purchase reprints of this article please e-mail: reprints@emeraldinsight.com

Or visit our web site for further details: www.emeraldinsight.com/reprints

Вам также может понравиться

- RPAДокумент7 страницRPAAdinaОценок пока нет

- Checklist - Optimizing Your YouTube ChannelДокумент3 страницыChecklist - Optimizing Your YouTube ChannelMasa Claudiu Mugurel100% (1)

- RPA Awareness Training Lesson 2Документ8 страницRPA Awareness Training Lesson 2Masa Claudiu MugurelОценок пока нет

- Tabel 2 - Matricea Riscurilor in Functie de Impact Si Probabilitate (Ierarhia Riscurilor)Документ3 страницыTabel 2 - Matricea Riscurilor in Functie de Impact Si Probabilitate (Ierarhia Riscurilor)Masa Claudiu MugurelОценок пока нет

- The Syntax of Complex Sentence - Sentence Negation (Course 1)Документ8 страницThe Syntax of Complex Sentence - Sentence Negation (Course 1)Corina Elena NiculaeОценок пока нет

- More Favorable Conditions For Business Creation and GrowthДокумент2 страницыMore Favorable Conditions For Business Creation and GrowthMasa Claudiu MugurelОценок пока нет

- Critical Article The Literary Significance of The Catcher in The RyeДокумент3 страницыCritical Article The Literary Significance of The Catcher in The RyeMasa Claudiu MugurelОценок пока нет

- The Syntax of Complex Sentence - Sentence Negation (Course 1)Документ8 страницThe Syntax of Complex Sentence - Sentence Negation (Course 1)Corina Elena NiculaeОценок пока нет

- The Syntax of Complex Sentence - Sentence Negation (Course 1)Документ8 страницThe Syntax of Complex Sentence - Sentence Negation (Course 1)Corina Elena NiculaeОценок пока нет

- Marketing Deals With Identifying and Meeting Human and Social NeedsДокумент5 страницMarketing Deals With Identifying and Meeting Human and Social NeedsMasa Claudiu MugurelОценок пока нет

- A Midsummer Night's DreamДокумент42 страницыA Midsummer Night's DreamMasa Claudiu MugurelОценок пока нет

- Res Essay IdeasДокумент6 страницRes Essay IdeasMasa Claudiu MugurelОценок пока нет

- 1 Fundamental Concepts: Defining MarketingДокумент9 страниц1 Fundamental Concepts: Defining MarketingMasa Claudiu MugurelОценок пока нет

- Victorian Architecture TermsДокумент1 страницаVictorian Architecture TermsMasa Claudiu MugurelОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (120)

- Print National Insurance Credits - Overview - GOV - UKДокумент12 страницPrint National Insurance Credits - Overview - GOV - UKApopei Ana MariaОценок пока нет

- MRMRT16330450000010851 NewДокумент4 страницыMRMRT16330450000010851 NewGirish kumar kushwahaОценок пока нет

- सूचना/NOTICE: Schedule Of InterviewДокумент77 страницसूचना/NOTICE: Schedule Of InterviewPadmabhooshan BabladiОценок пока нет

- National Policy For Urban Street Vendors 2004Документ12 страницNational Policy For Urban Street Vendors 2004neilОценок пока нет

- G.R. No. 146494 July 14, 2004 GOVERNMENT SERVICE INSURANCE SYSTEM, Cebu City Branch, Petitioner, MILAGROS O. MONTESCLAROS, RespondentДокумент6 страницG.R. No. 146494 July 14, 2004 GOVERNMENT SERVICE INSURANCE SYSTEM, Cebu City Branch, Petitioner, MILAGROS O. MONTESCLAROS, RespondentShally Lao-unОценок пока нет

- Mr. Muhammad Ayyaz Arshad AnsariДокумент1 страницаMr. Muhammad Ayyaz Arshad AnsariM Ayyaz Arshad AnsariОценок пока нет

- Welfare FacilitiesДокумент85 страницWelfare FacilitiesVipin Kumar KushwahaОценок пока нет

- Pet CT & CK Individual SplitДокумент38 страницPet CT & CK Individual SplitManikantaОценок пока нет

- 2023 Contribution Rate TableДокумент2 страницы2023 Contribution Rate TableMyrick Mae B. RuizОценок пока нет

- Our Interns CertificatesДокумент31 страницаOur Interns CertificatesemmanuelОценок пока нет

- Unit V Welfare of Special Categories of LabourДокумент49 страницUnit V Welfare of Special Categories of LabourAnithaОценок пока нет

- Social Security in America (Full Book) - Publication of The Social Security AdministrationДокумент328 страницSocial Security in America (Full Book) - Publication of The Social Security AdministrationNikolai HamboneОценок пока нет

- SSS CIR New Contribution Schedule - ER and EE - 22dec20 - 521pm 1Документ1 страницаSSS CIR New Contribution Schedule - ER and EE - 22dec20 - 521pm 1Marienhela MeriñoОценок пока нет

- Social Protection For Development A Review of DefinitionДокумент23 страницыSocial Protection For Development A Review of DefinitionTeddy LesmanaОценок пока нет

- Policy Brief 1: Social Grants South AfricaДокумент4 страницыPolicy Brief 1: Social Grants South AfricaAngelo-Daniel SeraphОценок пока нет

- DLCPM00312970000023340 NewДокумент6 страницDLCPM00312970000023340 NewAnshul KatiyarОценок пока нет

- Groot. Basic Income On The AgendaДокумент293 страницыGroot. Basic Income On The AgendargadeamerinoОценок пока нет

- Apy Chart PDFДокумент1 страницаApy Chart PDFVinay ChokhraОценок пока нет

- Unit 2 PDFДокумент19 страницUnit 2 PDFMir UmarОценок пока нет

- Social Security in IndiaДокумент15 страницSocial Security in IndiadranshulitrivediОценок пока нет

- A Strategy For Active Ageing: Alan WalkerДокумент19 страницA Strategy For Active Ageing: Alan WalkernegriRDОценок пока нет

- SSSДокумент91 страницаSSSLou Thez Geniza100% (1)

- Seminar HasilДокумент46 страницSeminar HasilWiwara AwisaritaОценок пока нет

- Scheduled Time Per AgentДокумент12 страницScheduled Time Per AgentAyaulym TyngushОценок пока нет

- Labour Welfare and Social SecurityДокумент6 страницLabour Welfare and Social SecurityDineshОценок пока нет

- Welfare of Special Categories of Labour: Unit - VДокумент43 страницыWelfare of Special Categories of Labour: Unit - VParameshwari ParamsОценок пока нет

- Electronic Contribution Collection List SummaryДокумент2 страницыElectronic Contribution Collection List SummaryKayePee BalendoОценок пока нет

- Deaconess Homecare Inc: Payroll Advice OnlyДокумент4 страницыDeaconess Homecare Inc: Payroll Advice OnlyDREE DREEОценок пока нет

- Ao239 1 PDFДокумент5 страницAo239 1 PDFAnonymous wqT95XZ5Оценок пока нет

- Apy Chart PDFДокумент1 страницаApy Chart PDFKaran VermaОценок пока нет