Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Income Tax Policy: Is A Single Rate Tax Optimum For Long-Term Economic Growth?

Загружено:

RebeccaChua0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

46 просмотров9 страницPurpose – The purpose of this paper is to show an optimum income tax policy, given that the government must raise sufficient tax revenue to fund public goods and services as well as income transfer programmes. The paper examines the different types of taxes and then suggests a policy that is efficient, equitable, easy to administer and leads to a higher level of economic growth.

Оригинальное название

Income Tax Policy: is a Single Rate Tax Optimum for Long-term Economic Growth?

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документPurpose – The purpose of this paper is to show an optimum income tax policy, given that the government must raise sufficient tax revenue to fund public goods and services as well as income transfer programmes. The paper examines the different types of taxes and then suggests a policy that is efficient, equitable, easy to administer and leads to a higher level of economic growth.

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

46 просмотров9 страницIncome Tax Policy: Is A Single Rate Tax Optimum For Long-Term Economic Growth?

Загружено:

RebeccaChuaPurpose – The purpose of this paper is to show an optimum income tax policy, given that the government must raise sufficient tax revenue to fund public goods and services as well as income transfer programmes. The paper examines the different types of taxes and then suggests a policy that is efficient, equitable, easy to administer and leads to a higher level of economic growth.

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 9

Income tax policy: is a single rate

tax optimum for long-term

economic growth?

Michael Busler

Richard Stockton College, School of Business, Galloway, New Jersey, USA

Abstract

Purpose The purpose of this paper is to show an optimum income tax policy, given that the

government must raise sufficient tax revenue to fund public goods and services as well as income

transfer programmes. The paper examines the different types of taxes and then suggests a policy that

is efficient, equitable, easy to administer and leads to a higher level of economic growth.

Design/methodology/approach A literature review has been done to find all scholarly work that

relates to income tax policy and its effect on economic growth. Results from endogenous growth

models have been utilised to determine both the significance and the magnitude of income tax policys

effect on the growth rate of real GDP.

Findings After examining the benefits of each type of taxation and reviewing the principles of

capitalism, a proportionate (single rate) tax of 12 per cent on all income would be approximately

revenue neutral in the USA, and would add to the growth of real GDP, thereby improving the standard

of living.

Research limitations/implications The paper concentrates on income tax policy in the USA.

While it is believed that the conclusions apply to virtually all market-based economies, cultural

differences in some countries may result in a modification of the conclusion to fit the society.

Practical implications In the USA today, the majority of people favour changing the current

income tax code. The debate is about what to change and how to change it. This debate is also

important to developing nations who try to set an income tax policy that reaches the goals while

encouraging growth.

Originality/value While the literature shows varying studies concerning the impact of tax policy,

there is a gap when searching for an optimum policy. Many scholars have made suggestions but none

of them seem to be optimal. This topic is of particular interest in the USA and the rest of the developed

and non-developed world, since the recent performance of GDP growth has been very slow and in

many instances negative. Most countries have tried combinations of monetary and fiscal policies to

encourage growth, but none seem to be working effectively. The solution may be to change income tax

policy. The proposal for an optimum income tax policy is new and different from any that has been

suggested as yet.

Keywords Tax policy, Economic growth, Flat rate tax, Progressive tax

Paper type Research paper

Introduction

A most difficult question facing societies who choose to implement a market economy

as the basis for their economic system deals with the manner in which tax revenue will

be collected. While there are a number of different philosophies concerning how taxes

should be levied and who should bear the burden of taxation, no comprehensive view

has become dominant.

The effect of this is that there are numerous taxes paid by everyone to all levels of

government. In the USA, federal income tax policy has become so complex and

distorted that there seems to be a general feeling that government has become

extremely inefficient and unfair with respect to raising tax revenue. The purpose of

this paper is to attempt to examine the current tax structure of the federal government

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at

www.emeraldinsight.com/2042-5961.htm

Received 3 January 2013

Revised 3 January 2013

Accepted 5 January 2013

World Journal of Entrepreneurship,

Management and Sustainable

Development

Vol. 9 No. 4, 2013

pp. 246-254

rEmerald Group Publishing Limited

2042-5961

DOI 10.1108/WJEMSD-01-2013-0008

246

WJEMSD

9,4

in general and specifically the complex issues of fairness and equity, and suggest a

federal income tax policy that meets the criteria of equity, efficiency and ease of

administration while creating no market distortions.

Historical perspective

In the USA, except for a brief period during and just after the Civil War (1860s), income

taxes were deemed by the Supreme Court to be unconstitutional. In 1913, the

constitution was amended to allow the federal government to place taxes on income.

Prior to 1913, most government revenue was in the form of duties and tariffs. Although

the initial tax rates were slightly progressive and modest (1-7 per cent), eventually both

the progressivity and the rates increased to a maximum marginal rate of 92 per cent.

The maximum rate has been reduced and increased several times in the past 80 years,

so that the maximum rate is 36 per cent today.

If tax revenue is to be raised by income taxes, three points must be addressed. First,

what type of tax shall be imposed? (Noting that the type will be defined by the changes

in the tax rate with respect to changes in income). Second, how will the tax base be

defined? Finally, what will be the rate of taxation?

Since 1913, the federal income tax has changed from slightly progressive to

very progressive, with the rate of progressivity also changing. As mentioned, the rate

has changed from 1 per cent to a maximum marginal rate of 92 per cent and reduced

to a maximum marginal rate of 36 per cent. The definition of the tax base has

also changed considerably, with income used for certain expenditures excluded from

the tax base.

Methods and principles of taxation

According to Hyman (2008), taxes are classified based on the change in the tax rate,

with respect to income, as income increases. A progressive tax is one in which the

tax rate increases as income increases. The logic seems to be that individuals

should be taxed based on some notion of the ability to pay. Progressive taxes

insure that as income increases, individuals pay disproportionately more taxes. The

burden of taxation is therefore placed on the upper income earners. Why this seems

to conform to some notion of fairness is questionable. Bittker (1969) notes that there

are a surprisingly large number of scholars who believe that progression seems

to be instinctively correct. Blum and Kalven (1953) concluded that it is difficult to

justify progression in taxes based on some concept or notion of benefit,

diminishing utility, sacrifice, ability to pay or economic stability. Rather, the case

only has strong appeal when progression is viewed as a means of reducing income

inequality.

The second type of taxation is a regressive tax. Here the tax rate declines as income

increases. There is very little logic to support regression unless a lump sum for benefit

received position is adopted. In this instance an individual would pay a fixed dollar

amount to receive a service. As an individuals income increased, this lump sum would

be a smaller percent of total income, thus making the tax regressive.

Because the average propensity to consume falls as income increases, any tax

placed on consumption, is regressive. These include sales tax, excise tax, turnover

tax and value-added tax, for instance. The greatest burdens of taxation are placed on

the lowest income earners.

There is, however, one argument for taxing consumption which will ultimately be

rejected herein, but does, none the less, have merit. That is, consumption is really a

247

Income tax

policy

better gauge to use to measure ability to pay than income (Hyman, 2008). This also

means that income applied to savings would be free of taxation.

A true proportional tax is one where the tax rate stays constant at all levels of

income. Here each individual would increase his tax liability proportionately, as

income increases. Each individual would pay exactly the same amount from each

dollar of taxable income earned, no matter how many or how few.

In 2011, The US Office of Management and Budget reported that 47.4 per cent of

federal government revenue came from progressive income taxes, 35.5 per cent

came from regressive social insurance taxes, 7.9 per cent from corporate income taxes,

which are progressive to the firm, but if they result in higher prices for goods

and services to the public, could be arguably regressive. The balance comes from

various taxes.

The question concerning the type of tax to levy is then dependent upon which

type of taxation is deemed to be fair and equitable by the majority. Mill (1894)

argued that fair and equitable could be found by examining equal sacrifice. Based

on diminishing marginal utility, equal sacrifice would occur with very progressive

tax rates.

Others have offered similar arguments, including Feldstein (1976), who said

that to achieve equity in taxation, post tax utility should be equalized using

progressive taxes.

There are three criteria for evaluating taxation (Hyman, 2008). First, policies should

be equitable, both horizontally and vertically, so that individuals with the same income

pay the same amount of taxes and that increases in tax rates conform to some notion of

fairness. Second, taxes should be efficient, thereby causing only minimal efficiency

losses in the private sector. Third, taxes should be relatively easy to administer. And, of

course, the policy must raise sufficient revenue.

A progressive tax, like the current federal income tax, may not conform to any of

these criteria. There is no horizontal equity since actual tax liability depends on the

mixture of consumption and savings an individual undertakes and how the tax law

treats the deductibility of those choices. For instance, if two individuals have the same

income, but one owns his mortgaged home while the other chooses to rent his home,

the actual tax liability could vary greatly.

On the issue of vertical equity, even those who favour progressivity will note that

the actual tax liability of high-income earners may be much lower than it appears if

those individuals dispose of their income in a tax-favourable manner or earn their

income as a capital gain rather than ordinary income. As a result the current federal

income tax system may be less progressive than believed and actual tax rates may not

really increase significantly as income increases.

On the issue of efficiency, the current progressive federal income tax may again fail

to meet the criteria. With progressive taxes, a natural occurrence would be to exclude

from taxation certain portions of disposition of income. This tends to artificially raise

some prices (home prices) and artificially lower some others (rents). Further, many

investment decisions are made not primarily for the potential return in response to

supply and demand conditions in a specific market, but rather for favourable tax

treatment. This distortion decreases efficiency.

Finally, the current federal income tax is a tremendous nightmare to administer

(more than three million words in the current tax code) and invites fraudulent

behaviour. Therefore, it appears, the current system seems to fail all three of the

criteria for evaluating taxation.

248

WJEMSD

9,4

Function of taxation

Ignoring for the moment the use of discretionary fiscal policy, a free market

interpretation for the purpose of taxation should be to fairly and equitably raise

enough revenue to exactly match the current level of government expenditures.

Beyond that, many learned economists have argued that tax policy should serve no

other function. Indeed some argue that this use of discretionary fiscal policy to offset

economic fluctuations is ineffective. Feldstein (1976) for instance, notes that overall

taxing and spending policies have no significant effect on the course of nominal

income, inflation, deflation or on cyclical fluctuations.

While raising revenue, the levying of taxes should be configured so that no undue

burden is placed on any individuals. It is then the belief that any tax placed on

consumption, which is regressive with respect to total income, is therefore not

consistent with the basic principles discussed herein and should not be considered.

Distribution of income

Considering that the means of production are privately owned and that the owners are

free to transact any asset in accordance with their desire to seek economic gain, the

income generated from these assets should reflect the value of the contribution.

Similarly, all inputs into the economy receive income in accordance with the value

of their contribution.

Many economists would argue that the resulting distribution of income is indeed

fair and just, because as Gregory and Stuart (1995), for instance, noted, factor

owners receive a reward equal to the factors marginal contribution to the economys

output. Because it is assumed that individuals are motivated primarily (although

not necessarily entirely) by self-interest, the granting of rewards according to

marginal productivity encourages improvements in the productivity of the resources.

This benefits not only the owner, but also the entire society. Altering of this

distribution by the government reduces incentives and is therefore viewed as

counter-productive, noting, of course, that in a compassionate society some

redistribution of income will occur. It is critical, however, that the federal tax system

be configured so as to have minimal impact on the prices in the markets, which

ultimately determine the income distribution. And that any and all redistribution of

income be accomplished in a fair and equitable manner. Again we will note that

the current progressive federal income tax system seems to be inefficient because

of the market distortions created.

Tax rates and economic growth

Before specifically addressing the issues of efficiency, equity, fairness and ease of

administration, an examination of changes in tax rates as it relates to economic growth

should be undertaken. Endogenous growth models are the most widely used and most

current. There are a number of scholars who have examined this issue and all reached

a similar conclusion.

Karras (1999) found that when utilising an endogenous growth model, changes in

the tax rate will alter real growth permanently. He utilised data from 11 Organization

of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) economies from 1960 to 1992. The

findings suggest that a higher tax rate permanently reduces the level of output.

A similar study was done by Padovano and Galli (2001). They used data from 23

OECD countries from 1950 to 1990 and an endogenous growth model. Using panel

regression, their econometric estimations found that the effective marginal income tax

249

Income tax

policy

rate was negatively correlated with economic growth and was robust to the

considerations of other growth determinants.

Poulson and Kaplan (2008) similarly employed an endogenous growth model. Their

data were compiled from each state in the USA. Their analysis revealed a significant

negative impact of higher marginal tax rates on economic growth.

Cassau and Lansing (2004) studied the growth effects of shifting from a progressive

income tax system to a single rate system. This study essentially examined the effect of

a constant marginal tax rate. They too found that this shift from progressive to

proportional tax policy would add to long-term economic growth.

A proposal

Consistent with the results previously mentioned, the lowest tax rate should result in

the highest economic growth. So a logical proposal would be for individuals, the

current progressive federal income tax could be replaced by a single rate (proportional)

tax of 12 per cent on all income earned above a livable minimum, with no deductions.

Income would be defined as all compensation for labour, rental income, interest income,

previously untaxed pension payments, dividend income, proprietors income and the

gain on the sale of an asset in the period the gain is realised.

With reference to businesses organised as separate legal entities (corporations,

LLC), a single rate tax of 12 per cent on all income, deducting only explicit costs from

revenue to define income (an annual depreciation expense should not be included in

expenses, further discussion follows).

This proposal will conform to all criteria used to evaluate taxation. First, it will be

equitable. Horizontally, all individuals (adjusting only for the number of dependents)

with similar incomes would pay exactly the same amount of taxes regardless of how

they freely chose to dispose of that income. Vertically, this proposal would also be

equitable. Taxes would be levied proportionately to the ability to pay. The current

progressive system raises rates disproportionately as income increases.

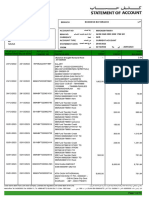

For example, suppose we examine the tax liability for individuals who are

married, the head of a household and have two children. Suppose further that we

estimate a livable minimum (maybe the poverty rate is a good approximation) of

$30,000 per year. Table I shows the actual tax liability for five similar individuals with

different incomes.

This example shows the most vertically equitable method of taxation. Above a

livable minimum, every individual will pay $0.12 of every dollar earned to federal

income tax, which means the other $0.88 will go directly to the income earner,

regardless of how much total income is received. The highest income earners will pay

the most tax dollars, but the increases in tax liability will be proportional.

On the issue of efficiency, this proposal would be extremely efficient in that, by

allowing no deductions, all purchasing decisions would be made by free choice so that

Person Gross income Livable minimum Taxable income Tax liability

1 30,000 30,000 0 0

2 50,000 30,000 20,000 2,400

3 200,000 30,000 170,000 20,400

4 500,000 30,000 470,000 56,400

5 1,000,000 30,000 970,000 116,400

Table I.

Tax liability for five

individuals with

different incomes

250

WJEMSD

9,4

the resulting price and quantity represent true free market equilibrium. This method

would further eliminate any disincentives to produce more, work more and earn more.

In addition, it would tend to increase capital formation and improve the personal

savings rate. It would not discourage consumption, nor place an undue burden on the

lower classes as would be the case with taxes on consumption.

Third, it would be extremely easy to administer. An individual would simply sum

all relevant income for the time period, subtract what would be defined as a livable

minimum and multiply the balance by 12 per cent. There would be no complicated tax

forms, no cumbersome record keeping systems and no concern about determining

what income will be liable for taxation. Further, because the marginal tax rate would be

low, it would discourage dishonesty and fraud. It is also believed that taxpayers would

not feel so badly concerning tax payments.

This tax policy would utilise the Simons (1938) definition of comprehensive income

with the exception that only capital gains that have been realised would be taxable.

Simons noted that income is an indicator of the exercise of control over the use of

societys scarce resource. Therefore income is a good measure of an individuals power

to purchase goods and services, and so provides the fairest base for taxation.

The justification

Initially, it was noted that three points must be addressed concerning tax revenue

philosophy. The first point considers the type of tax. For reasons discussed herein

concerning the distortions and counter-productivity of a progressive tax code, the

notion of a progressive tax as being fundamentally consistent with the principles of

capitalism seems illogical. Further a regressive tax places undue burdens on the people

who can least afford to have these burdens. Again we will note that any tax placed

solely on consumption will result in regressivity, no matter how it is presented. Hall

and Rabushka (1985) and others have argued to exclude from taxation, income that is

devoted to saving and investment, thereby leaving only consumption to be taxed. This

argument results in an essentially a regressive tax.

Hall and Rabushka (1995) further argued that the consumption tax is proper

because it is the embodiment of the principle that people should be taxed on what they

take out, not what they put in. However, what individuals initially take out of the

economy is income. Eventually all of it goes back in, whether in the form of

consumption or future consumption (saving). This argument would suggest that if an

extremely high-income earner chose to save the vast majority of that income, he could

be virtually free of taxes for that period. Further, if the ability to pay criteria is at least

considered, then an individuals tax liability should be based on his total income

regardless of his decisions concerning the disposition of that income as consumption

or saving.

The other argument presented, which also applies to the concept of taxing dividend

income of individuals, is that an attempt should be made to avoid double taxation at

any level. Hall and Rabushka (1985) said that if saving is taxed and then the income

earned from this saving is taxed again, the result is a double taxation. Similarly if a

corporation pays dividends from after-tax income, and an individuals dividend income

is taxed on the personal level, this again is a double taxation. However, is it not true

that virtually all income earned is received from revenue that has already been taxed?

When a good or service is provided, the consumer pays for that transaction with

after-tax dollars. The provider of the service then receives these after-tax dollars from

the consumer, and is taxed on them. Further, when the provider uses the after-tax

251

Income tax

policy

dollars to purchase other goods and services, the next provider is taxed on dollars

that have already been taxed, perhaps a number of times. The key here is that when

new income is earned by a different legal entity, it should be taxed in that period,

regardless of how that income is disposed in the future.

This proposal includes the taxation of dividends with the reason being that

dividends are transferred from one legal entity (a corporation) to another legal entity

(a stockholder). Using the same logic as above, the dividend income becomes new

income to the separate legal entity (the stockholder) and should therefore be included

in the tax base. Business owners may choose to avoid this situation by organising

the business as an LLC, a sole proprietor or a partnership. Thereby, business income is

taxed only once, since the business is not a separate legal entity, and is not liable for

taxes. In reality, business owners may not do this because they desire the liability

protection (although an LLC provides that), ease in the ability to raise new capital

that a corporation offers, ease of transfer of ownership and other advantages offered

by establishing the business as legally separate. The bottom line is that if these

advantages are desired, the price is taxation of dividends as new income to

the individual.

It is, therefore, concluded that a proportional tax on all new income by each legally

definable entity (individuals and/or corporations) regardless of how that income is

earned or how it is disposed, is optimal for the economy. Further, addressing the

second point concerning the definition of the tax base, this proposal utilises total

income earned regardless of the manner in which earnings occurred and regardless

of how that income is disposed. The third point concerns the rate. By allowing a broad

tax base with minimal forgiveness of initial income, the rate will be kept low. The 12

per cent rate is approximately revenue neutral. The idea is to construct a base that

allows the rate to be as low as possible, without placing any undue burdens.

One final note to this proposal deals with the method by which depreciation expense

is computed by business. Hall and Rabushka (1985) argued that the full cost of any

fixed asset should be taken in the year in which it is purchased. This may result in the

business having a negative taxable income for the period. In that case no tax would

be due in that period and the negative tax liability can be carried forward with no time

limit. Then when the asset is sold, the full proceeds are taken as income and are

therefore taxable. This proposal agrees with this concept for business.

While business will deduct investments made towards the production of goods or

services, individuals may not. That is to say if an individual invests in a business, the

investment is made with after-tax income, while a business will invest with before-tax

income. The difference is that business investment is directly into their activities while

an individuals investment is made into a business. Therefore, the individuals

investment is indirect and should be made from after-tax dollars. This is consistent

with the concept of new income being created and liable for taxation when an exchange

occurs between two separate legal entities.

Conclusion

Given that no method of taxation will be deemed fair by every individual, this proposal

probably represents the least unfair method of taxation. The goal of tax policy

should be to raise enough revenue to pay for the federal governments spending

requirements, in a manner that is consistent with the basic principles of capitalism and

meets the criteria of being equitable, efficient and easy to administer. This includes, of

course, configuring a tax system that causes minimal market distortions.

252

WJEMSD

9,4

This proposal meets the criteria of both horizontal and vertical equity, and is

supported by the principle that all individuals and corporations (separate legal

entities) should bear the tax liability in a manner that is proportional to the ability to

pay. Therefore, tax liability is incurred on all new income, no matter how that income

is earned nor in what manner that income is so disposed. The vertical equity issue is

further supported by allowing an individual to earn a livable minimum amount of

income before any tax liability is due. The livable amount is determined by the number

of dependents and the status as head of a household.

This proposal meets the criteria of efficiency, since it has virtually no impact on any

specific decisions regarding the earning or use of income. Further, it restores the

incentives to increase the value of the output of every individual and business. It will

increase capital formation by eliminating over-taxation of successful individuals

whose high incomes become the basis for new capital. It does not discourage

consumption, nor place an undue burden on the lower classes that would be seen with

any tax on consumption.

Finally, this revenue neutral proposal would be extremely easy to administer and,

because of the very low rate, would discourage dishonestly and fraud. The tax form

would be only a few lines. Once income for the period is totalled, only a livable

deduction depending on household and dependents status would be allowed. Then the

12 per cent rate is applied.

References

Bittker, B.I. (1969), Accounting for federal tax subsidies in the national budget, National Tax

Journal, Vol. 22 No. 2, p. 244.

Blum, W.J. and Kalven, H. Jr (1953), The Uneasy Case for Progressive Taxation, University of

Chicago Press, Chicago, IL.

Cassau, S.P. and Lansing, K.J. (2004), Growth effects of shifting from a graduated-rate system to

a flat tax, Economic Inquiry, Vol. 42 No. 2, pp. 194-213.

Feldstein, M. (1976), On the theory of tax reform, Journal of Public Economics, Vol. 6, July-

August, pp. 77-104.

Gregory, P.R. and Stuart, R.C. (1995), Comparative economic systems, in Comparative Economic

Systems, 5th ed., Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, MA.

Hall, R.E. and Rabushka, A. (1985), The Flat Tax, Hoover Institution Press, Stanford, CA.

Hall, R.E. and Rabushka, A. (1995), Simplify, simplify, New York Times, 8 February,

New York, NY.

Hyman, D.N. (2008), Publ ic Finance, 9th ed., Southwestern Publishing Company,

New York, NY.

Karras, G. (1999), Taxes and growth: testing the neoclassical and endogenous growth models,

Contemporary Economic Policy, Vol. 17 No. 2, pp. 177-188.

Mill, J.S. (1894), Principles of political economy with some of their applications to social

philosophy, Vol. II No. 99, p. 401.

Padovano, F. and Galli, E. (2001), Tax rates and economic growth in the OECD countries,

Economic Inquiry, Vol. 39 No. 1, pp. 44-57.

Poulson, B.W. and Kaplan, J.G. (2008), State income taxes and economic growth, Cato Journal,

Vol. 28 No. 1, pp. 53-71.

Simons, H. (1938), Personal Income Taxation, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL.

253

Income tax

policy

Further reading

Hall, R.E. and Rabushka, A. (1983), Low Tax, Simple Tax, Flat Tax, McGraw-Hill Book Company,

New York, NY.

About the author

Dr Michael Busler is an Associate Professor of Finance, Finance Track Coordinator and a Fellow

at the William J. Hughes Center for Public Policy at Richard Stockton College. Previously he had

held positions at Pennsylvania State University, Rutgers University and The University of

Delaware. He teaches undergraduate courses in Finance and Game Theory and MBA courses

in Managerial Economics, Applied Financial Analysis and New Ventures. In addition, he has

worked as a Financial Analyst for FMC Corp and Ford Motor Company and has been a successful

entrepreneur having owned several businesses, mostly in the Real Estate development field.

He earned his doctorate at Drexel University. Dr Michael Busler can be contacted at:

michael.busler@stockton.edu

To purchase reprints of this article please e-mail: reprints@emeraldinsight.com

Or visit our web site for further details: www.emeraldinsight.com/reprints

254

WJEMSD

9,4

Вам также может понравиться

- Estmt - 2022 03 31Документ12 страницEstmt - 2022 03 31Laura MCGОценок пока нет

- Texas LLC Update 0509141033Документ43 страницыTexas LLC Update 0509141033tortdogОценок пока нет

- Leida Mae Bumanlag Refresher B Answers To 2018 Bar Exam Questions On TaxationДокумент11 страницLeida Mae Bumanlag Refresher B Answers To 2018 Bar Exam Questions On TaxationLei BumanlagОценок пока нет

- Principles and Practice of Taxation Lecture NotesДокумент20 страницPrinciples and Practice of Taxation Lecture NotesSony Axle100% (11)

- Invoice: Charge DetailsДокумент2 страницыInvoice: Charge DetailsAnna BanaОценок пока нет

- (Digest) Chavez v. OngpinДокумент1 страница(Digest) Chavez v. OngpinHomer SimpsonОценок пока нет

- OnlineДокумент3 страницыOnlinepedro laskoski100% (1)

- Httpsjacksonemc - smarthub.coopservicessecuredbillPdfService2023 06-9-1112157.pdfaccount 1112157×tamp 1686289249000&sДокумент2 страницыHttpsjacksonemc - smarthub.coopservicessecuredbillPdfService2023 06-9-1112157.pdfaccount 1112157×tamp 1686289249000&sRegina HudsonОценок пока нет

- Research 2Документ36 страницResearch 2Hilario Domingo ChicanoОценок пока нет

- Change Advice Letter For Customer PaymentsДокумент1 страницаChange Advice Letter For Customer PaymentsLiu Inn100% (2)

- Objectives and Principles of Taxation - GeeksforGeeksДокумент5 страницObjectives and Principles of Taxation - GeeksforGeeksLMRP2 LMRP2Оценок пока нет

- Tax System: KPMG's Questionable Tax Shelters Ethics CaseДокумент15 страницTax System: KPMG's Questionable Tax Shelters Ethics CaseWriting OnlineОценок пока нет

- The Case For A Progressive Tax: From Basic Research To Policy RecommendationsДокумент27 страницThe Case For A Progressive Tax: From Basic Research To Policy Recommendationsbaapuu5695Оценок пока нет

- Tax Policy PrimerДокумент4 страницыTax Policy PrimerFrancis ChikombolaОценок пока нет

- Taxation, Individual Actions, and Economic Prosperity: A Review by Joshua Rauh and Gregory KearneyДокумент12 страницTaxation, Individual Actions, and Economic Prosperity: A Review by Joshua Rauh and Gregory KearneyHoover InstitutionОценок пока нет

- Buque - Prelim Exam-Income TaxationДокумент3 страницыBuque - Prelim Exam-Income TaxationVillanueva, Jane G.Оценок пока нет

- Tax Literature ReviewДокумент5 страницTax Literature Reviewc5nr2r46100% (2)

- RITESHДокумент94 страницыRITESHRahul RajОценок пока нет

- Who Wins and Who Loses? Debunking 7 Persistent Tax Reform MythsДокумент18 страницWho Wins and Who Loses? Debunking 7 Persistent Tax Reform MythsCenter for American ProgressОценок пока нет

- Tax Inefficiencies and Alternative SolutionsДокумент13 страницTax Inefficiencies and Alternative SolutionsAbdullahОценок пока нет

- Essay FinalДокумент6 страницEssay FinalHananОценок пока нет

- RITESHДокумент94 страницыRITESHrohilla smythОценок пока нет

- Taxes in The United StatesДокумент36 страницTaxes in The United StatesYermekОценок пока нет

- ACT 205 - Tax Theory Practice - Lecture 1Документ8 страницACT 205 - Tax Theory Practice - Lecture 1Kaycia HyltonОценок пока нет

- Escaping True Tax Liability of The Government Amidst PandemicsДокумент7 страницEscaping True Tax Liability of The Government Amidst PandemicsMaria Carla Roan AbelindeОценок пока нет

- Critical Review Paper On TaxДокумент4 страницыCritical Review Paper On TaxShannia LouieОценок пока нет

- Taxation SystemДокумент16 страницTaxation SystemShadman ShoumikОценок пока нет

- Govt PoliciesДокумент8 страницGovt PoliciesDanyal TahirОценок пока нет

- Tax Inefficiencies and Alternative SolutionsДокумент13 страницTax Inefficiencies and Alternative SolutionsAbdullahОценок пока нет

- ReadingДокумент12 страницReadinglaraghorbani12Оценок пока нет

- Taxation Is The ProcessДокумент7 страницTaxation Is The ProcessJaneil FrancisОценок пока нет

- Importance of Tax in EconomyДокумент7 страницImportance of Tax in EconomyAbdul WahabОценок пока нет

- BACC3 - Antiniolos, FaieДокумент21 страницаBACC3 - Antiniolos, Faiemochi antiniolosОценок пока нет

- Determinant Factors of Exist Gaps Between The Tax Payers and Tax Authority in Ethiopia, Amhara Region The Case of North Gondar ZoneДокумент6 страницDeterminant Factors of Exist Gaps Between The Tax Payers and Tax Authority in Ethiopia, Amhara Region The Case of North Gondar ZonearcherselevatorsОценок пока нет

- CH 1Документ20 страницCH 1tomas PenuelaОценок пока нет

- Tax Policy Research Paper TopicsДокумент4 страницыTax Policy Research Paper Topicsfzmgp96k100% (1)

- Taxation IssuesДокумент23 страницыTaxation IssuesBianca Jane GaayonОценок пока нет

- TaxationДокумент34 страницыTaxationShyamKumarKCОценок пока нет

- Demooji Tax in PracticeДокумент2 страницыDemooji Tax in PracticePao AbuyogОценок пока нет

- Fiscal Policy - Taxation in PakistanДокумент21 страницаFiscal Policy - Taxation in Pakistanali mughalОценок пока нет

- This Content Downloaded From 196.191.248.6 On Fri, 06 May 2022 17:05:39 UTCДокумент33 страницыThis Content Downloaded From 196.191.248.6 On Fri, 06 May 2022 17:05:39 UTCTahir DestaОценок пока нет

- Theoretical FrameworkДокумент14 страницTheoretical Frameworkfadi786Оценок пока нет

- Research Paper TaxesДокумент6 страницResearch Paper Taxesyqxvxpwhf100% (1)

- Tax ReformsДокумент9 страницTax ReformsAmreen kousarОценок пока нет

- Thesis TaxationДокумент8 страницThesis Taxationgjgm36vk100% (2)

- Ch. 14 - Taxes and Government SpendingДокумент25 страницCh. 14 - Taxes and Government SpendingMr RamОценок пока нет

- Developing Consistent Tax Bases For Broad-Based Reform: Fiscal Associates, IncДокумент10 страницDeveloping Consistent Tax Bases For Broad-Based Reform: Fiscal Associates, IncThe Washington PostОценок пока нет

- Federal Tax RevenuesДокумент12 страницFederal Tax RevenuesJOijiewjfОценок пока нет

- Taxation JunaДокумент551 страницаTaxation JunaJuna DafaОценок пока нет

- Tax Policies and Its Economic FluctuationsДокумент14 страницTax Policies and Its Economic FluctuationsZubairОценок пока нет

- Day 3 SlidesДокумент25 страницDay 3 SlidesEyob MogesОценок пока нет

- Taxation DiazДокумент3 страницыTaxation DiazRyan DiazОценок пока нет

- The Impact of Taxation On The Economic DevelopmentДокумент3 страницыThe Impact of Taxation On The Economic DevelopmentppppОценок пока нет

- Ans Taxation 1Документ23 страницыAns Taxation 1Priscilla AdebolaОценок пока нет

- University of Rwanda Huye Campus Principle of Taxation Cat Marketing Departiment MPIRANYA Jean Marie Vianney REG NUMBER: 220009329Документ5 страницUniversity of Rwanda Huye Campus Principle of Taxation Cat Marketing Departiment MPIRANYA Jean Marie Vianney REG NUMBER: 220009329gatete samОценок пока нет

- University of Rwanda Huye Campus Principle of Taxation Cat Marketing Departiment MPIRANYA Jean Marie Vianney REG NUMBER: 220009329Документ5 страницUniversity of Rwanda Huye Campus Principle of Taxation Cat Marketing Departiment MPIRANYA Jean Marie Vianney REG NUMBER: 220009329gatete samОценок пока нет

- Tax Evasion and Financial Instability: Peterson K OziliДокумент10 страницTax Evasion and Financial Instability: Peterson K OziliMihaela ApostolОценок пока нет

- Presentation of Taxation - ScribdДокумент17 страницPresentation of Taxation - ScribdAbdellah BelhouariОценок пока нет

- Tax AssignmentДокумент6 страницTax AssignmentCarlos Takudzwa MudzengerereОценок пока нет

- M222994Документ5 страницM222994Carlos Takudzwa MudzengerereОценок пока нет

- Tax Working Group Briefing PaperДокумент20 страницTax Working Group Briefing PaperbernardchickeyОценок пока нет

- Taxation and Fiscal PoliciesДокумент279 страницTaxation and Fiscal PoliciesFun DietОценок пока нет

- Paper HuberДокумент24 страницыPaper HuberDave SanzОценок пока нет

- Taxation 1 MOA HOMEOWNERSДокумент22 страницыTaxation 1 MOA HOMEOWNERSRaymundo CanindoОценок пока нет

- Taxation of MncsДокумент47 страницTaxation of MncsUdayabhanu SwainОценок пока нет

- Tech TP FTДокумент24 страницыTech TP FTTeresa TanОценок пока нет

- Explain The Effect of Taxation On: A, ProductionДокумент10 страницExplain The Effect of Taxation On: A, ProductionTony LithimbiОценок пока нет

- Brueggemann 2017Документ38 страницBrueggemann 2017hoangpvrОценок пока нет

- ICICI Bank Rewards: April 1, 2022 April 19, 2022Документ3 страницыICICI Bank Rewards: April 1, 2022 April 19, 2022avisinghoo7Оценок пока нет

- This Study Resource Was: Homework On CashДокумент6 страницThis Study Resource Was: Homework On CashYukiОценок пока нет

- Transaction History: Name: Account Number: Address: Card Number: Reporting Period: EmailДокумент2 страницыTransaction History: Name: Account Number: Address: Card Number: Reporting Period: EmailCarybel DiazОценок пока нет

- Quarterly Cash Flow Projections Template: Company NameДокумент10 страницQuarterly Cash Flow Projections Template: Company NamehamisayubuОценок пока нет

- Vikash K PDFДокумент1 страницаVikash K PDFexcelОценок пока нет

- Position PaperДокумент1 страницаPosition PaperAlvy Faith Pel-eyОценок пока нет

- Practical Q Bcom Programme III YrДокумент11 страницPractical Q Bcom Programme III YrPhung Huyen NgaОценок пока нет

- Oracle ARДокумент6 страницOracle ARMr. JalilОценок пока нет

- B3iv19000098 - Ramdani PDFДокумент1 страницаB3iv19000098 - Ramdani PDFelem usОценок пока нет

- Account StatementДокумент10 страницAccount Statementalihassan459001Оценок пока нет

- Online Merchant Assessment FormДокумент4 страницыOnline Merchant Assessment Formbplo mexicoОценок пока нет

- Business Mathematics Worksheet Week 4Документ6 страницBusiness Mathematics Worksheet Week 4300980 Pitombayog NHSОценок пока нет

- 6072 p1 Lembar JawabanДокумент49 страниц6072 p1 Lembar JawabanAhmad Nur Safi'i100% (2)

- New Provisional BillДокумент55 страницNew Provisional Billrafi ud dinОценок пока нет

- Full Blown Case Commissioner Vs PhilphosДокумент4 страницыFull Blown Case Commissioner Vs PhilphosMary Imogen GdlОценок пока нет

- Statement of Account: Penyata AkaunДокумент4 страницыStatement of Account: Penyata AkaunMuhammad ZiqriОценок пока нет

- Account Statement PDFДокумент2 страницыAccount Statement PDFGopal ShejulОценок пока нет

- Income Tax NotesДокумент16 страницIncome Tax NotesAntonette Contreras DomalantaОценок пока нет

- Gul BargaДокумент916 страницGul BargaShihan Ali KhanОценок пока нет

- ANZ Global Transaction Banking File Formats 2014Документ265 страницANZ Global Transaction Banking File Formats 2014Ded MarozОценок пока нет

- Success Gyaan Invoice - 1Документ2 страницыSuccess Gyaan Invoice - 1Sanat DesaiОценок пока нет