Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Signature Pedagogies in The Professions

Загружено:

malcrowe0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

52 просмотров8 страницPedagogy across different academic disciplins

Оригинальное название

Signature Pedagogies in the Professions

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документPedagogy across different academic disciplins

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

52 просмотров8 страницSignature Pedagogies in The Professions

Загружено:

malcrowePedagogy across different academic disciplins

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 8

52 Ddalus Summer 2005

The psychoanalyst Erik Erikson once

observed that if you wish to understand

a culture, study its nurseries. There

is a similar principle for the understand-

ing of professions: if you wish to under-

stand why professions develop as they

do, study their nurseries, in this case,

their forms of professional preparation.

When you do, you will generally detect

the characteristic forms of teaching and

learning that I have come to call signature

pedagogies. These are types of teaching

that organize the fundamental ways in

which future practitioners are educated

for their new professions. In these signa-

ture pedagogies, the novices are instruct-

ed in critical aspects of the three funda-

mental dimensions of professional work

to think, to perform, and to act with integ-

rity. But these three dimensions do not

receive equal attention across the profes-

sions. Thus, in medicine many years are

spent learning to perform like a physi-

cian; medical schools typically put less

emphasis on learning how to act with

professional integrity and caring. In

contrast, most legal education involves

learning to think like a lawyer; law

schools show little concern for learn-

ing to perform like one.

We all intuitively know what signature

pedagogies are. These are the forms of

instruction that leap to mind when we

rst think about the preparation of

members of particular professionsfor

example, in the law, the quasi-Socratic

interactions so vividly portrayed in The

Paper Chase. The rst year of law school

is dominated by the case dialogue meth-

od of teaching, in which an authoritative

and often authoritarian instructor en-

gages individual students in a large class

of many dozens in dialogue about an ap-

pellate court case of some complexity. In

medicine, we immediately think of the

phenomenon of bedside teaching, in

which a senior physician or a resident

leads a group of novices through the dai-

ly clinical rounds, engaging them in dis-

cussions about the diagnosis and man-

agement of patients diseases.

I would argue that such pedagogical

signatures can teach us a lot about the

personalities, dispositions, and cultures

Lee S. Shulman

Signature pedagogies in the professions

Lee S. Shulman, a Fellow of the American Acade-

my since 2002, is president of the Carnegie Foun-

dation for the Advancement of Teaching and

Charles E. Ducommun Professor of Education

Emeritus at Stanford University. His latest books

are Teaching as Community Property: Essays

on Higher Education (2004) and The Wisdom

of Practice: Essays on Teaching, Learning, and

Learning to Teach (2004).

2005 by the American Academy of Arts

& Sciences

of their elds. And though signature

pedagogies operate at all levels of educa-

tion, I nd that professions are more

likely than the other academic disci-

plines to develop distinctively interest-

ing ones. That is because professional

schools face a singular challenge: their

pedagogies must measure up to the stan-

dards not just of the academy, but also of

the particular professions. Professional

education is not education for under-

standing alone; it is preparation for ac-

complished and responsible practice in

the service of others. It is preparation for

good work. Professionals must learn

abundant amounts of theory and vast

bodies of knowledge. They must come

to understand in order to act, and they

must act in order to serve.

In the Carnegie Foundations studies

of preparation for the professions, we

have gone into considerable depth to

understand the critical role of signature

pedagogies in shaping the character of

future practice and in symbolizing the

values and hopes of the professions. We

have become increasingly cognizant of

the many tensions that surround profes-

sional preparation, from the competing

demands of academy and profession to

the essential contradictions inherent in

the multiple roles and expectations for

professional practitioners themselves.

The importance of the particular forms

of teaching that characterize each pro-

fession has become ever more salient in

the course of our inquiry. Above all, we

have found it fruitful to observe closely

the pedagogy of the professions in

action.

Behold a rst-year class on contracts

at a typical law school. Immediately one

notices that the rectangular room is not

designed like most lecture halls: the 120

seats are arranged in a semicircle so that

most students can see many of the other

students. The instructor, clearly visible

behind the lectern, is at the center of the

long side of the rectangle. Rather than

lecturing, he tends to ask questions of

one student at a time, chasing the initial

question with a string of follow-ups. At

certain points, he will turn his attention

to another student, and stick with her

for a while. Again and again he asks a

student to read aloud the precise word-

ing of a contract or legal ruling; when

confusion arises, he repeatedly asks the

student to look carefully at the language.

The instructor may use the board or the

overhead projector to record specic

phrases, to list legal principles, or to note

the names of court cases or precedents.

Throughout the hour, the law professor

faces the students, interacting with them

individually through exchanges of ques-

tions and answers, and only occasionally

writing anything on the board. The stu-

dents can see each other as they partici-

pate, and can respond easily if the pro-

fessor solicits additional responses. But

its relatively rare for students to address

one another directly.

Now consider a lecture course in flu-

id dynamics as taught at a typical engi-

neering school. The seats all face the

front of the room; discussion among

students is apparently not a high prior-

ity here. Although the teacher faces his

class when he introduces the days topic

at the beginning of the session, soon he

has turned to the blackboard, his back to

the students. The focal point of the ped-

agogy is clearly mathematical represen-

tations of physical processes. He is furi-

ously writing equations on the board,

looking back over his shoulder in the di-

rection of the students as he asks, of no

one in particular, Are you with me?

A couple of afrmative grunts are suf-

cient to encourage him to continue.

Meanwhile, the students are either writ-

ing as furiously as their instructor, or

Signature

pedagogies

in the

professions

Ddalus Summer 2005 53

54 Ddalus Summer 2005

Lee S.

Shulman

on

professions

& profes-

sionals

they are sitting quietly planning to re-

view the material later in study groups.

There is very little exchange between

teacher and students, or between stu-

dents. There is almost no reference to

the challenges of practice in this teach-

inglittle sense of the tension between

knowing and doing. This is a form of

teaching that engineering shares with

many of the other mathematically inten-

sive disciplines and professions; it is not

the signature of engineering.

Quite a different classroom style is evi-

dent when one visits a design studio that

meets in the same building of the same

engineering school. Here students as-

semble around work areas with physical

models or virtual designs on computer

screens; there is no obvious front of the

room. Students are experimenting and

collaborating, building things and com-

menting on each others work without

the mediation of an instructor. The fo-

cal point of instruction is clearly the de-

signed artifact. The instructor, whom an

observer identies only with some dif-

culty, circulates among the work areas

and comments, critiques, challenges, or

just observes. Instruction and critique

are ubiquitous in this setting, and the

formal instructor is not the only source

for that pedagogy.

Consider, nally, the varieties of bed-

side teaching and clinical rounds used in

medical schools. Here the classroom is

the hospital, where a clinical triadthe

patient, the senior attending physician,

and the student physiciansfacilitates

the teaching and learning. Since much

of medical pedagogy is peer driven, only

one year of training or experience may

differentiate the student from her in-

structor. The ritual of case presentation,

pointed questions, exploration of alter-

native interpretations, working diagno-

sis, and treatment plan is routine. The

patient may be physically present or rep-

resented by a case record or, these days,

by a video. There is no question that the

instruction centers on the patient, and

not on medicine in some more abstract

sense. The dance changes as we move

from the patients rst visit to the fol-

low-up, but the basic moves remain the

same.

In the Carnegie Foundations studies,

we have spent a lot of time observing,

analyzing, and documenting how teach-

ing and learning occur in many kinds of

settings. We not only watch and record,

but also meet with faculty members

and students individually and in focus

groups. We review teaching materials

and the examinations used to evaluate

the progress of students. To the extent

that we identify signature pedagogies,

we nd modes of teaching and learning

that are not unique to individual teach-

ers, programs, or institutions. Indeed,

if there is a signature pedagogy for law,

engineering, or medicine, we should

be able to nd it replicated in nearly all

the institutions that educate in those

domains.

Signature pedagogies are important

precisely because they are pervasive.

They implicitly dene what counts as

knowledge in a eld and how things be-

come known. They dene how knowl-

edge is analyzed, criticized, accepted,

or discarded. They dene the functions

of expertise in a eld, the locus of au-

thority, and the privileges of rank and

standing. As we have seen, these ped-

agogies even determine the architec-

tural design of educational institutions,

which in turn serves to perpetuate these

approaches.

Asignature pedagogy has three di-

mensions. First, it has a surface structure,

which consists of concrete, operational

acts of teaching and learning, of show-

ing and demonstrating, of questioning

and answering, of interacting and with-

holding, of approaching and withdraw-

ing. Any signature pedagogy also has a

deep structure, a set of assumptions about

how best to impart a certain body of

knowledge and know-how. And it has an

implicit structure, a moral dimension that

comprises a set of beliefs about profes-

sional attitudes, values, and dispositions.

Finally, each signature pedagogy can al-

so be characterized by what it is notby

the way it is shaped by what it does not

impart or exemplify. A signature peda-

gogy invariably involves a choice, a se-

lection among alternative approaches

to training aspiring professionals. That

choice necessarily highlights and sup-

ports certain outcomes while, usually

unintentionally, failing to address other

important characteristics of professional

performance.

We can see the relevance of all these

features if we examine, for example, the

signature pedagogy of legal case meth-

ods. This signature pedagogys surface

structure entails a set of dialogues that are

entirely under the control of an authori-

tative teacher; nearly all exchanges go

through the teacher, who controls the

pace and usually drives the questions

back to the same student a number of

times. The discussion centers on the

law, as embodied in a set of texts rang-

ing from judicial opinions that serve as

precedents, to contracts, testimonies,

settlements, and regulations; in the legal

principles that organize and are exem-

plied by the texts; and in the expecta-

tion that students know the law and are

capable of engaging in intensive verbal

duels with the teacher as they wrestle to

discern the facts of the case and the prin-

ciples of its interpretation.

The deep structure of the pedagogy rests

on the assertion that what is really being

taught is the theory of the law and how

to think like a lawyer. The subject matter

is not black-letter law, as, for example, in

British law schools, but the processes of

analytic reasoning characteristic of legal

thinking. Legal theory is about the con-

frontation of views and interpretations

hence the inherently competitive and

confrontational character of case dia-

logue as pedagogy.

The implicit structure of case dialogue

pedagogy has several features. We ob-

served several interactions in which stu-

dents questioned whether a particular

legal judgment was fair to the parties, in

addition to being legally correct. The in-

structor generally responded that they

were there to learn the law, not to learn

what was fairwhich was another mat-

ter entirely. This distinction between

legal reasoning and moral judgment

emerged from the pedagogy as a tacit

principle. Similarly, the often brutal na-

ture of the exchanges between instruc-

tor and student imparted in rather stark

terms a sense of what legal encounters

entail. These lessons might also be called

the hidden curriculum of case dialogue

pedagogy.

Finally, we can examine what is miss-

ing in this signature pedagogy. The miss-

ing signature here is clinical legal edu-

cationthe pedagogies of practice and

performance. While these pedagogies

can be found in all law schools, they are

typically on the margins of the enter-

prise, are rarely required, and are often

ungraded.

I would also call our attention to three

typical temporal patterns of signature

pedagogies in the professions: the per-

vasive initial pedagogy that frames and

pregures professional preparation, as

in the law; the pervasive capstone ap-

prenticeships, as in the clinical bedside

teaching of medicine or in the compara-

tively brief period of student teaching in

teacher education; and the sequenced

and balanced portfolio, as in the medley

Ddalus Summer 2005 55

Signature

pedagogies

in the

professions

56 Ddalus Summer 2005

Lee S.

Shulman

on

professions

& profes-

sionals

of analysis courses, laboratories, and

design studios in engineering, or in the

interaction of hermeneutic, liturgical,

homiletic, and pastoral pedagogies in

the education of clergy.

Up to this point, I have emphasized the

distinctive characteristics of signature

pedagogiesthe characteristics by

which we can tell them apart. In spite

of the differences among their surface

structures, signature pedagogies also

share a set of common features. These

features may help explain the relative

durability and robustness of these ap-

proaches to teaching and learning. In-

deed, I believe these features evolved

precisely because they facilitate student

learning of professionally valued under-

standings, skills, and dispositions. Enu-

merating them will help to explain the

persistence and generality of signature

pedagogies in the professions.

First, as observed earlier, signature

pedagogies are both pervasive and rou-

tine, cutting across topics and courses,

programs and institutions. Case dia-

logue methods in law, for example, are

routinely encountered by law students

in nearly all their doctrinal courses

torts, Constitutional law, contracts, civil

procedure, and criminal. Teachers and

students can be inventive or creative

within the boundary conditions of these

teaching frameworks, but the frame-

works themselves are quite well dened.

Of course, everyone understands the

danger of routine, but routine also has

great virtues. Learning to do complex

things in a routine manner permits both

students and teachers to spend far less

time guring out the rules of engage-

ment, thereby enabling them to focus

on increasingly complex subject matter.

Also, the pedagogical routines differ in

purpose: legal education routines devel-

op habits of the mind, whereas clergy

education routines also develop habits

of the heart, and clinical education rou-

tines develop habits of the hand.

Pedagogies that bridge theory and

practice are never simple. They entail

highly complex performances of obser-

vation and analysis, reading and inter-

pretation, question and answer, conjec-

ture and refutation, proposal and re-

sponse, problem and hypothesis, query

and evidence, individual invention and

collective deliberation. To the extent

that the substance of these complex

performances changes with each ses-

sion, chapter, or patient, the cognitive

and behavioral demands on both stu-

dents and faculty would be overwhelm-

ing if it were not possible to routinize

signicant components of the pedagogy.

To put it simply, signature pedagogies

simplify the dauntingly complex chal-

lenges of professional education because

once they are learned and internalized,

we dont have to think about them; we

can think with them. From class to class,

topic to topic, teacher to teacher, assign-

ment to assignment, the routine of ped-

agogical practice cushions the burdens

of higher learning. Habit makes novelty

tolerable and surprise sufferable. The

well-mastered habit shifts new learning

into our zones of proximal development,

transforming the impossible into the

merely difcult.

But habits are both marvelous scaf-

folds for complex behavior as well as

dangerous sources of rigidity and perse-

veration. Thus we shall also see that the

very utility of habit that is a source of

signature pedagogies power also con-

tributes to their most serious vulnerabil-

ity: Signature pedagogies, by forcing all

kinds of learning to t a limited range of

teaching, necessarily distort learning in

some manner. They persist even when

they begin to lose their utility, precisely

because they are habits with few coun-

tervailing forces. Since faculty members

in higher education rarely receive direct

preparation to teach, they most often

model their own teaching after that

which they themselves received. This

apprenticeship of observation is pow-

erful even among precollegiate teachers

who do undertake pedagogical training.

Moreover, since the physical layout of

classrooms so typically tracks the prem-

ises of a elds signature pedagogies, the

very architecture of teaching encourages

pedagogical inertia. Only the most radi-

cal of new conditionssuch as sharp

changes in the organization or econom-

ics of professional practice or in the

technologies of teachingare sufcient

forces to redirect that inertia.

Another feature of signature pedago-

gies is that they nearly always entail pub-

lic student performance. Without stu-

dents actively performing their roles

as interlocutors in legal dialogues, as

student physicians reporting on cases

in clinical rounds, as designers of arti-

facts, or as active critics in the engineer-

ing studiothe instruction simply cant

proceed. This emphasis on students ac-

tive performance reduces the most sig-

nicant impediments to learning in

higher education: passivity, invisibility,

anonymity, and lack of accountability.

The pedagogies command student vigi-

lance, which in turn causes learners to

feel highly visible in the classroom,

even vulnerable. Again, the case dia-

logue method will provide our example:

at any moment the law professor may

call on students (the infamous cold

call) to answer questions about the case

prepared for a given class, or for argu-

ments or counterarguments in discus-

sion of a case. Because so much depends

on student contributionsin dialogue,

in diagnostic work-up, in the design of

artifacts, in practice teaching, or in ther-

apeutic encountersthere is also an in-

herent uncertainty associated with these

situations: the direction the discussion

takes is jointly produced by the instruc-

tors plan and the students responses,

elaborations, and inventions.

Indeed, in these signature pedagogies,

students are not only active but interac-

tive. Students are accountable not only

to teachers, but also to peers in their re-

sponses, arguments, commentaries, and

presentations of new data. They are ex-

pected to participate actively in the dis-

cussions, rounds, or constructions; they

are also expected to make relevant con-

tributions that respond directly to previ-

ous exchanges. Signature pedagogies are

pedagogies of uncertainty. They render

classroom settings unpredictable and

surprising, raising the stakes for both

students and instructors. Interestingly,

learning to deal with uncertainty in the

classroom models one of the most cru-

cial aspects of professionalism, namely,

the ability to make judgments under

uncertainty.

Finally, uncertainty, visibility, and

accountability inevitably raise the emo-

tional stakes of the pedagogical encoun-

ters. Uncertainty produces both excite-

ment and anxiety. These pedagogies

create atmospheres of risk taking and

foreboding, as well as occasions for ex-

hilaration and excitement. Indeed, I

would argue that an absence of emotion-

al investment, even risk and fear, leads

to an absence of intellectual and forma-

tional yield; Alison Davis used to refer to

adaptive anxiety as a necessary feature

of learning. However, teachers must

manage levels of anxiety so that teaching

produces learning rather than paralyzing

the participants with terror. When the

emotional content of learning is well

sustained, we have the real possibility of

pedagogies of formationexperiences of

teaching and learning that can influence

the values, dispositions, and characters

Ddalus Summer 2005 57

Signature

pedagogies

in the

professions

58 Ddalus Summer 2005

Lee S.

Shulman

on

professions

& profes-

sionals

of those who learn. And when these

experiences are interactive rather than

individual, when they embody the per-

vasive culture of learning within a eld,

they offer even more opportunity for

character formation.

Howard Gardner has proposed the

concept of compromised work to de-

scribe forms of professional practice in

which the fundamental ethical princi-

ples of a profession are violated. I would

propose a parallel concept of compro-

mised pedagogy to describe a somewhat

different phenomenon. Instead of recog-

nizing only the tensions between the

technical and the ethical dimensions of

professional learning as those that are

regularly compromised, I would argue

that a sound professional pedagogy must

seek balance, giving adequate attention

to all the dimensions of practicethe

intellectual, the technical, and the mor-

al. Pedagogy is compromised whenever

any one of these dimensions is unduly

subordinated to the otherseven when

an adequate intellectual preparation is

subordinated to an ethical perspective

(which rarely happens outside the prep-

aration of teachers and clergy).

Professional action is often character-

ized by a tension between acting in the

service of ones client and acting in a

manner that protects the public interest

more broadly. Thus lawyers are torn be-

tween acting as zealous advocates or as

ofcers of the court. They can also ex-

perience the tension between acting in

their own self-interest or in the interests

of either their client or the greater socie-

ty. Engineers can design to reduce costs

and maximize prots, or to increase

safety and environmental protection.

Physicians can order tests and interven-

tions that maximize the potential bene-

ts to their patients, or can act to control

costs and the likelihood of overprescrip-

tion. Teachers can maximize their per-

ceived efcacy by teaching to the bene-

t of those students most likely to earn

high test scores, or can teach in ways

that equalize educational opportunity

and emphasize educational ends wheth-

er or not they are externally examined.

Every profession can be characterized

by these inherent tensions, which are

never fully resolved, but which must be

managed and balanced with every ac-

tion. As John Dewey observed about

many of the problems of science, we

dont solve them; we get over them.

Responsible professional pedagogy must

address these tensions and provide stu-

dents with the capabilities to deal with

them.

Since individual professions adapt to

their own signatures, which, however

effective, are prone to inertia, we can

learn a great deal by examining the sig-

nature pedagogies of a variety of pro-

fessions and asking how they might

improve teaching and learning in pro-

fessions for which they are not now sig-

natures. What might laboratory instruc-

tion in the sciences learn from examin-

ing the studio instruction of architecture

and mechanical engineering? How

might the challenges of integrating the

texts of legal theory and the enactment

of legal practice prot from taking seri-

ously the clinical education of physi-

cians, or the learning of homiletic by

clergy? The comparative study of signa-

ture pedagogies across professions can

offer alternative approaches for improv-

ing professional education that might

otherwise not be considered. Indeed, I

believe that education in the liberal arts

and sciences can prot from careful con-

sideration of the pedagogies of the pro-

fessions.

I have written about signature pedago-

gies as if they are nearly impossible to

change. There are, however, several

conditions that can trigger substantial

changes in the signature pedagogies of

professions. The objective conditions of

practice may change so much that those

pedagogies that depend on practice will

necessarily have to change. A dramatic

example is developing in medicine and

nursing: Bedside teaching became these

elds signature pedagogy at a time

when a much larger percentage of pa-

tients were hospitalized, and for much

longer periods of time. Under those con-

ditions, patientsthe teaching material

for clinical instructionremained in

place long enough to provide extended

teaching opportunities. Today, by con-

trast, we nd far more medicine and sur-

gery practiced either as outpatient pro-

cedures or with much shorter hospital

stays. For example, surgical removal of

the gallbladder once entailed at least a

weeks hospitalization; that procedure is

now done laparoscopically, and patients

do not even remain overnight. Recovery

now takes a few days instead of several

weeks. Under these kinds of changing

conditions, the signature pedagogies of

medicine will have to change.

New technologies of teaching via the

Internet; Web-based information seek-

ing; computer-mediated dialogues; col-

laborations and critiques in the design

studio; powerful representations of

complex and often unavailable exam-

ples of professional reasoning, judg-

ment, and actionall create an oppor-

tunity for reexamining the fundamental

signatures we have so long taken for

granted. In surgery, the signature peda-

gogy for learning new procedures has

been watch one, do one, teach one

an approach that is undeniably fraught

with the likelihood of error and signi-

cant danger to the patient. Now new

forms of simulation, the use of surgical

mannequins and robotlike models, cog-

nitive task analysis, and cognitive ap-

prenticeship create opportunities to

make substantial changes in that peda-

gogy, and therefore to dramatically mod-

ify its signatures.

Finally, severe critiques of the quality

of professional practice and service,

which occur with great frequency these

days, can accelerate the pace with which

the most familiar pedagogical habits

might be reevaluated and redesigned.

The ethical scandals that have beset

many professionswell illustrated by

our colleagues in the GoodWork Pro-

jectmay create the social conditions

needed to reconsider even the most tra-

ditional signature pedagogies.

One thing is clear: signature pedago-

gies make a difference. They form habits

of the mind, habits of the heart, and

habits of the hand. As Erikson observed

in the context of nurseries, signature

pedagogies pregure the cultures of pro-

fessional work and provide the early

socialization into the practices and val-

ues of a eld. Whether in a lecture hall

or a lab, in a design studio or a clinical

setting, the way we teach will shape how

professionals behaveand in a society

so dependent on the quality of its profes-

sionals, that is no small matter.

Ddalus Summer 2005 59

Signature

pedagogies

in the

professions

Вам также может понравиться

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Poet Prophets of The Old Testament: John RogersonДокумент10 страницPoet Prophets of The Old Testament: John RogersonmalcroweОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5795)

- Poet Prophets of The Old Testament: John Rogerson: Lecture 1: The Rediscovery of Hebrew Poetry in The Eighteenth CenturyДокумент11 страницPoet Prophets of The Old Testament: John Rogerson: Lecture 1: The Rediscovery of Hebrew Poetry in The Eighteenth CenturymalcroweОценок пока нет

- Poet Prophets of The Old Testament: John Rogerson: Lecture 4: The Servant Songs of Isaiah Chapters 42 To 53Документ14 страницPoet Prophets of The Old Testament: John Rogerson: Lecture 4: The Servant Songs of Isaiah Chapters 42 To 53malcrowe100% (1)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Isaiah - NotesДокумент14 страницIsaiah - NotesmalcroweОценок пока нет

- Poet Prophets of The Old Testament: John RogersonДокумент13 страницPoet Prophets of The Old Testament: John RogersonmalcroweОценок пока нет

- Matter and Consciousness - Iain McGilcristДокумент34 страницыMatter and Consciousness - Iain McGilcristmalcrowe100% (1)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- 110 SCO John Duns Scotus Philosphical WritingsДокумент383 страницы110 SCO John Duns Scotus Philosphical Writingsmalcrowe100% (1)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- SC Specimen English 06Документ38 страницSC Specimen English 06malcroweОценок пока нет

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Nectre MK ! ManualДокумент7 страницNectre MK ! ManualmalcroweОценок пока нет

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- 8ways - HomeДокумент6 страниц8ways - HomemalcroweОценок пока нет

- Derrida and KierkegaardДокумент14 страницDerrida and KierkegaardmalcroweОценок пока нет

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- 12St Eng Ass6 EssayДокумент5 страниц12St Eng Ass6 EssaymalcroweОценок пока нет

- Persuasive TechniquesДокумент2 страницыPersuasive TechniquesmalcroweОценок пока нет

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Deep English - Theory and PracticeДокумент11 страницDeep English - Theory and PracticemalcroweОценок пока нет

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- C. S. Lewis PHD - ThesisДокумент217 страницC. S. Lewis PHD - ThesismalcroweОценок пока нет

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- John CassianДокумент223 страницыJohn Cassianmalcrowe100% (2)

- Sennett, Richard - The Open CityДокумент5 страницSennett, Richard - The Open Cityhellosilo100% (1)

- Horkheimer On ReligionДокумент58 страницHorkheimer On ReligionmalcroweОценок пока нет

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Karl Barth On The Nature of ReligionДокумент21 страницаKarl Barth On The Nature of ReligionmalcroweОценок пока нет

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Accomplishment Report: Triala National High SchoolДокумент4 страницыAccomplishment Report: Triala National High SchoolAisley ChrimsonОценок пока нет

- The Webster and Wind ModelДокумент1 страницаThe Webster and Wind ModelKushagra VarmaОценок пока нет

- What Does Inquiry Look Like/Sound Like/Feel Like?: Excellent Resources For Inquiry-Based/related Teaching and LearningДокумент4 страницыWhat Does Inquiry Look Like/Sound Like/Feel Like?: Excellent Resources For Inquiry-Based/related Teaching and LearningChau NguyenОценок пока нет

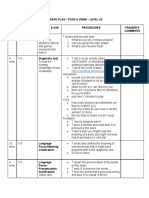

- Lesson Plan - Food & Drink - Level A2 Time Interaction Stage & Aim Procedures Trainer'S Comments Lead-InДокумент4 страницыLesson Plan - Food & Drink - Level A2 Time Interaction Stage & Aim Procedures Trainer'S Comments Lead-InCương Nguyễn DuyОценок пока нет

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Lesson Plan in Grade 6 Second Quarter Week 1 Day 5 I. ObjectivesДокумент5 страницLesson Plan in Grade 6 Second Quarter Week 1 Day 5 I. ObjectivesJIMMY NARCISEОценок пока нет

- Abstract Nouns Board GameДокумент2 страницыAbstract Nouns Board GameNina Ortiz BravoОценок пока нет

- L Addison Diehl-IT Training ModelДокумент1 страницаL Addison Diehl-IT Training ModelL_Addison_DiehlОценок пока нет

- Computer Standards & Interfaces: David C. ChouДокумент7 страницComputer Standards & Interfaces: David C. ChouAndrés LizarazoОценок пока нет

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- PE 7 3rd CotДокумент4 страницыPE 7 3rd CotBeaMaeAntoni100% (5)

- The Effects of Bilingualism On Students and LearningДокумент20 страницThe Effects of Bilingualism On Students and Learningapi-553147978100% (1)

- HG G11 Module 5 RTPДокумент11 страницHG G11 Module 5 RTPben beniolaОценок пока нет

- Effective Teaching Techniques StrategiesДокумент14 страницEffective Teaching Techniques StrategiesJAY MIRANDAОценок пока нет

- Joe Schroeder & Tim Berger - Super-Mind oДокумент8 страницJoe Schroeder & Tim Berger - Super-Mind ogimОценок пока нет

- Handout For Inquiries Investigations and ImmersionДокумент5 страницHandout For Inquiries Investigations and Immersionapollo100% (1)

- FS 2 Episode 5Документ6 страницFS 2 Episode 5Jeselle Azanes Combate BandinОценок пока нет

- Assertive CommunicationДокумент30 страницAssertive CommunicationranadhirenОценок пока нет

- UTS - Midterm ReviewДокумент16 страницUTS - Midterm ReviewAira JaeОценок пока нет

- Post B BSC Unit PlanДокумент3 страницыPost B BSC Unit Planvarshasharma05100% (4)

- This Study Resource WasДокумент1 страницаThis Study Resource WasKyralle Nan AndolanaОценок пока нет

- Young Learners Can Do Statements PDFДокумент1 страницаYoung Learners Can Do Statements PDFQuân Nguyễn VănОценок пока нет

- Competency Iceberg Model 160408160233Документ51 страницаCompetency Iceberg Model 160408160233Zibanex SebaloОценок пока нет

- Pre DefenseДокумент19 страницPre DefenseTasi Alfrace CabalzaОценок пока нет

- Lecture Notes - Recurrent Neural NetworksДокумент11 страницLecture Notes - Recurrent Neural NetworksBhavin PanchalОценок пока нет

- 1 TEACHING PROFESSION WPS OfficeДокумент21 страница1 TEACHING PROFESSION WPS Officemarianbuenaventura03100% (1)

- Managing UpwardДокумент51 страницаManaging UpwardCartada OtsoОценок пока нет

- DR. REYES INTERVIEW QUESTIONNAIRE For BRONOLAДокумент4 страницыDR. REYES INTERVIEW QUESTIONNAIRE For BRONOLAJanie-lyn BronolaОценок пока нет

- Ignition - The SlidesДокумент61 страницаIgnition - The SlidesErik EdwardsОценок пока нет

- The Art of ReportingДокумент4 страницыThe Art of ReportingTOPdeskОценок пока нет

- Career Objectives For Resume or Sample Resume ObjectivesДокумент10 страницCareer Objectives For Resume or Sample Resume ObjectivesAnonymous q0irDXlWAmОценок пока нет

- Master in English 1 - Midterm Oral Test Type AДокумент5 страницMaster in English 1 - Midterm Oral Test Type AAna Luisa Quintela de MoraesОценок пока нет

- World Geography - Time & Climate Zones - Latitude, Longitude, Tropics, Meridian and More | Geography for Kids | 5th Grade Social StudiesОт EverandWorld Geography - Time & Climate Zones - Latitude, Longitude, Tropics, Meridian and More | Geography for Kids | 5th Grade Social StudiesРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (2)