Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

17094800

Загружено:

Linda PertiwiАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

17094800

Загружено:

Linda PertiwiАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Factors inuencing consumers online

shopping in China

Wen Gong, Rodney L. Stump and Lynda M. Maddox

Abstract

Purpose The purpose of this paper is to develop an understanding of the factors inuencing Chinese

consumers to shop online by exploring the effects of user demographic characteristics and media

characteristics on shopping intention.

Design/methodology/approach A nationwide online survey of 503 Chinese consumers was carried

out to test the proposed conceptual model of online shopping intention using hierarchical regression.

The results support most of the proposed hypotheses.

Findings Chinese consumers age, income, education and marital status, and their perceived

usefulness are signicant predictors of online shopping intention.

Research limitations/implications Future research should use actual online purchases as the

dependent variable and explore the effects of product characteristics, merchants and intermediate

characteristics, as well as environmental inuences in online shopping behavior.

Practical implications Consideration of individual differences in explaining Chinese consumers

online buying intention could provide a better understanding of users adoption of the internet as a

shopping and transaction channel, as well as enhance an e-tailers market targeting and segmentation

effectiveness. E-marketers should incorporate features that can enhance online shopping efciency.

Originality/value Given the tremendous growth of B2C e-commerce in China, there is a critical need

for understanding what drives Chinese consumers to shop online. As one of the few large-scale

empirical studies on Chinese consumers online shopping behavior, these results will enable

e-marketers to better design their e-marketing strategies that cater to Chinese consumers changing

needs and lifestyles and improve their online shopping experiences and satisfaction.

Keywords Consumer behaviour, Internet, Shopping, Chinese consumers, Online shopping intentions,

B2C e-commerce

Paper type Research paper

Introduction

China now has 420 million internet users (CNNIC, 2010), representing the highest per

country usage in the world. With growing disposable income, the hundreds of millions of

netizens[1] are spending more and more on information and communication products and

services compared to their daily necessities, thus creating huge prospects for the

development of e-commerce and a digital economy in China. While many countries

worldwide were severely hit by the global recession, Chinas online retail market appeared to

be unaffected and has actually been growing steadily. Recent data reveal that China had

87.88 million users shopping on the Internet compared to 74 million the previous year

(CNNIC, 2009). This rapid growth represents opportunities as well as challenges for both

domestic and international marketers operating in the e-commerce space. Thus it is crucial

for e-marketers to understand what drives Chinese consumers to shop on the Internet in

order to design e-marketing strategies that caters to their changing needs and lifestyles and

improve their online shopping experiences and satisfaction.

PAGE 214

j

JOURNAL OF ASIA BUSINESS STUDIES

j

VOL. 7 NO. 3 2013, pp. 214-230, Q Emerald Group Publishing Limited, ISSN 1558-7894 DOI 10.1108/JABS-02-2013-0006

Wen Gong is based in the

Department of Marketing,

Howard University School

of Business, Washington,

DC, USA. Rodney L. Stump

is based in the Department

of Marketing, Towson

University, Towson,

Maryland, USA.

Lynda M. Maddox is based

at The George Washington

University, Washington, DC,

USA

Received 13 February 2013

Accepted 17 March 2013

Despite the surge in internet usage in China, analysts and researchers have questioned

whether Chinese consumers will become avid online shoppers. They point to Chinas cultural

preference for face-to-face business interactions as well as regulatory issues as factors that

may inhibit the development of online shopping (Raven et al., 2007; Rein, 2008).

While there is a growing body of research exploring consumers online shopping behavior in

Western context, far less is known in other parts of the world (Stafford et al., 2004). Thus,

whether these studies and associated theories are generalizable to other cultural contexts

such as China remains largely unknown. To date, relatively few empirical studies have been

carried out in the Chinese context. Given the tremendous growth this market is experiencing,

an in-depth understanding of the underlying motivations, attitudes and behaviors of Chinese

online shoppers is needed if marketers and advertisers are to inuence consumers online

buying decisions. This paper intends to ll some of this knowledge gap by empirically

investigating the determinants of Chinese consumers online shopping intentions.

In the following section, we reviewboth the Chinese online retail market and factors identied

in the existing literature that inuence consumers online buying intentions. Next, we present

our conceptual model and a series of hypotheses derived from it. Following that, we

describe our methodology, present the results of our survey, discuss the implications of

these ndings and tender recommendations for future research.

Literature review

Overview of Chinas online retail market

One manifestation of Chinas continuous rapid economic growth during the past two

decades is its consumers swelling consumption power (Zhao et al., 2008). As a result of the

growing affordability and availability of Internet access, more and more Chinese consumers

are using the internet for information, entertainment and communication purposes. At the

same time, Chinese consumers increasing understanding of online applications, a more

transparent and convenient online shopping environment and expanding investments by

companies have turned more and more Chinese netizens into online shoppers. Evidence of

this is reected in Chinas online retail market value reaching USD 18.8 billion in 2008 with a

vigorous growth rate of 128.5 percent in 2008 (Lee, 2009). Rising against the global

economic crisis, Chinas online shopping penetration rate has reached 24.8 percent and the

online B2C (business-to-consumer) annual growth rate is expected to exceed 100 percent

over the next two years (CNNIC, 2009; Lee, 2009).

One decade after the establishment of the rst B2C web site 8848.com in 1999, Chinas B2C

e-commerce has entered a stage of rapid development (Weng and Lee, 2009; Shanghai

Business Review, 2010). In contrast to most Western markets, C2C (consumer to consumer)

e-commerce (akin to eBays model) currently dominates Chinas online shopping market with

93.2 percent of total online sales in 2008 (CNNIC, 2009). Exemplifying this is Taobao, the

largest e-tailer in China whose web site allows buyers to shop in C2Cbazaars as well as B2C

branded stores. However, the online B2C market is expected to rapidly grow and become

the main driver behind the market expansion in the future as the B2C platform matures and

more local and foreign rms use this model to enter the market (Lee, 2009; Shanghai

Business Review, 2010).

Chinese netizens have greatly increased their online spending over the years. The average

spending online reached RMB1,600 (USD 234.3) in 2008 (IResearch, 2009; Lee, 2009) (see

Figure 1 for trends from 2003 to 2008). Like their Western counterparts, the online shopping

lists of Chinese consumers have also expanded a great deal from the initial simple selection

of books, music and video products to include a more extensive array of product categories

including apparel, housewares, digital products and many others.

Critics posit that e-commerce will not work in China, arguing that Chinese consumers are

traditionally conservative savers who refuse to buy on credit, distrust online vendors due to

privacy and quality concerns, and need to feel and touch a product before purchasing it

(Rein, 2008). Such perceptions may be in a state of ux as things have changed dramatically

VOL. 7 NO. 3 2013

j

JOURNAL OF ASIA BUSINESS STUDIES

j

PAGE 215

in China during the past three decades. The implementation of the one-child family policy

and the rapid transition to a market economy have remolded the Chinese society culturally,

as well as economically. Younger generations of Chinese hold a set of cultural values

strikingly different from those of their parents and older generations (Gong et al., 2004).

Young Chinese are more individualistic, novelty-seeking, admire foreign-made products,

and have a heightened sense of brand and status consciousness (Gong and Li, 2008).

Indeed, they have become the trend setters in almost every product and service category

fromstreet fashion to mobile phones and online purchases. Therefore, it is not surprising that

several market research reports have found that young and educated consumer segments

with higher income level are mainly the early adopters of online shopping in China (Lee,

2009; Rein, 2008).

Characterized by high technology and low entry barriers, Chinas online shopping market is

very dynamic and highly competitive, yet it holds great promise (Lee, 2009). In recent years,

the government has attached great importance to e-commerce as a means of spurring

Chinas economy and has released a series of policies to regularize and guide Internet and

e-commerce development, mainly through the 11th Five-Year Plan and the 2006-2020

National Informatization Development Strategy (CNNIC, 2009).

Despite these positive factors, China is not a country where it is easy for foreign rms to

operate online effectively and compete. Online sales and logistics are separated

everywhere in China and cash on delivery is still the main payment method for online

shopping (Shanghai Business Review, 2010). Geographical diversity, cultural barriers, lack

of cultural understanding, the fast-changing business environment and government

regulations, and especially the poor distribution networks and the lack of a safe and efcient

online payment mechanism all make this market less accessible to foreign rms (Lee, 2009).

CNNICs surveys have consistently shown that Chinese internet users are less involved in

e-commerce activities such as online shopping and payment, compared to their use of the

internet as a tool for entertainment, communication and information. The relatively low

adoption of e-commerce activities by Chinese consumers lags that of their Western

counterparts, especially Americans (Zhao et al., 2008).

This recap of the Chinese market not only highlights the importance of and an imminent need

for more research on Chinese online shoppers but also implies that Internet marketing

strategies developed in Western countries may not be applicable in the Chinese context.

Figure 1 Online shoppers average online spending per year

PAGE 216

j

JOURNAL OF ASIA BUSINESS STUDIES

j

VOL. 7 NO. 3 2013

Factors inuencing consumers online shopping

The increasing popularity and proliferation of online shopping has stimulated widespread

research aimed at understanding what inuence consumers online shopping behavior.

Earlier research sought to develop proles of internet buyers and identify predictors of

consumers intention and adoption of online shopping. More recently, research has begun to

focus on consumer site commitment, online shopping satisfaction and e-loyalty (online

repurchasing) (e.g. Ha, 2006; Li et al., 2006; Massad et al., 2006; Park and Kim, 2006).

Synthesizing studies in this area from 1994 through 2002, Cheung et al. (2005) provided a

critical and comprehensive review of the theories and empirical results of consumer online

behavior. The theory of planned behavior (TPB), theory of reasoned action (TRA), and

technology acceptance model (TAM) were identied as the dominant conceptual bases in

the surveyed literature. Five major categories of determinants of consumer online behavior

were identied:

1. Consumer characteristics such as consumer demographics, attitude, motivation,

perceived risk and trust.

2. Product characteristics such as price and product type.

3. Merchants and intermediate characteristics such as brand, service, privacy and security

control.

4. Environmental inuences such as exposure, market uncertainty, and competition.

5. Medium characteristics such as ease of use and information quality.

Chang et al. (2005) and Zhou et al. (2007) have also conducted meta-analyses on the

antecedents of consumers adoption of online shopping.

Conceptual model and hypotheses

Our study chooses to concurrently focus on two dimensions identied as being signicant

determinants of consumer online behavior, namely consumer and medium characteristics.

Specically, our model focuses on online shopping intentions as the dependent variable,

based on Fishbein and Ajzens (1975; Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980) theory of reasoned action

(TRA) which posits that beliefs inuence attitudes, which lead to intentions, and nally to

behaviors. We dene online shopping intentions as users likelihood to engage in online

shopping or buying activities, following the precedent of Chen et al. (2002). The

independent variables in our model include demographics and perceived risk, as aspects of

consumer characteristics, and perceptions of ease of use and usefulness, as aspects of the

medium characteristics (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Model of factors inuencing Chinese consumers online shopping intentions

VOL. 7 NO. 3 2013

j

JOURNAL OF ASIA BUSINESS STUDIES

j

PAGE 217

Consumer demographics. Consumer demographics are the most frequently studied area in

online shopping research. While there is abundant evidence that consumers demographic

traits such as gender, age, income, education, and marital status are associated with their

online shopping behavior (Liebermann and Stashevsky, 2009; Zhou et al., 2007), the extant

empirical literature reports many inconsistent ndings. We include these factors as the

baseline for our analysis and to provide additional evidence to help resolve these

inconsistencies.

Consider rst gender. Men were reported to hold the same (Alreck and Settle, 2002) or even

more favorable (van Slyke et al., 2002) perceptions towards online shopping than their

female counterparts, despite the fact that women usually have much more positive attitudes

toward shopping in general and towards both store and catalogue shopping in particular.

Explanations for such a gender pattern in the online setting have been offered from different

perspectives, for example, women were reported to perceive higher risk in online

purchasing than do men even when controlling for differences in Internet usage (Garbarino

and Strahilevitz, 2004); men and women exhibited different shopping orientations while

women were more recreational-oriented and motivated by social interactions, men were

more convenience-oriented and care less about face-to-face contacts (Swaminathan et al.,

1999); men and women are interested in different types of product when shopping on the

Internet (Jayawardhena et al., 2007; Zhou et al., 2007); e-shoppers are more likely to be male

than female because e-shopping involves a computer technology with specic masculine

associations (Dholakis and Chiang, 2003). In addition, men and women also show

signicant differences in online information search (Yoo-Kyoung and Bailey, 2008), women

demonstrate a stronger need than men for tactile cues in product evaluation (Citrin et al.,

2003), and women were found to be less satised than men with their online shopping

experience (Doolin et al., 2005; Kimand Kim, 2004; Rogers and Harris, 2003). Another study

also reported more men than women participated in online auctions (Fallows, 2005),

indicating that consumers online buying behavior varies not only by gender but also by

shopping formats (Shehryar, 2008). Summarizing these rationales, we posit:

H1a. Chinese male consumers are likely to hold higher online shopping intentions than

their female counterparts.

The existing research shows conicting results about the effect of age in predicting online

shopping. Several studies have found a positive relationship (Bhatnagar et al., 2000; Donthu

and Garcia, 1999; Doolin et al., 2005; Liebermann and Stashevsky, 2009) while others

reported a negative one (Joines et al., 2003; Swinyard and Smith, 2003) or no relationship (Li

et al., 1999; Rohm and Swaminathan, 2004). Zhou et al. (2007) assert that this inconsistency

across research ndings may be a function of the lack of a standard age categorization

scheme being used across studies. Looking to the broader adoption of innovation literature,

particularly studies that have pertained to information and communications technologies

(ICT) and services mediated by ICT, such as computers (Stoneman, 1983), the Internet

(Kiiski and Pohjola, 2002), automatic teller machines (Murdock and Franz, 1983), and

Internet banking and shopping (Eastin, 2002), there is a substantial body of evidence that

suggests that consumer innovators and early adopters tend to be younger, have higher

levels of income, and are more educated (Dickerson and Gentry, 1983; Gatignon and

Robertson, 1991; Rogers, 1995). In light of this, we propose:

H1b. There is an inverse relationship between Chinese consumers age and their

intention to shop online.

Common wisdomhas it that better educated consumers are more likely to be exposed to the

internet technology and thus have more condence in using the internet as a medium for

shopping (Hui and Wan, 2007). However, mixed effects were identied regarding a

consumers educational level on his/her online shopping intention. Some have reported a

positive relationship (Li et al., 1999; Liao and Cheung, 2001; Swinyard and Smith, 2003;

Susskind, 2004) while others did not (Bellman et al., 1999; Donthu and Garcia, 1999;

Mahmood et al., 2004, Liebermann and Stashevsky, 2009). As noted above, higher

PAGE 218

j

JOURNAL OF ASIA BUSINESS STUDIES

j

VOL. 7 NO. 3 2013

education levels often have been related to the adoption of other information and

communications technologies (ICT) and services mediated by ICT, which leads us to tender:

H1c. The higher the educational level of Chinese consumers, the more likely they will

intend to shop online.

As for income, it is well documented that online shoppers tend to earn more money than

traditional store shoppers (e.g. Mahmood et al., 2004; Susskind, 2004; Doolin et al., 2005).

Similarly, higher incomes generally show a high correlation with the adoption of other

information and communications technologies (ICT) and services mediated by ICT. Hence,

we propose:

H1d. The higher the income level of Chinese consumers, the more likely they will shop

online.

The effect of marital status on online shopping intentions is also not clear. Bhatnagar et al.

(2000) and Liebermann and Stashevsky (2009) have reported an insignicant effect. On the

other hand, Kim and Kim (2004) have found the number of children to be a signicant

predictor of consumer online shopping intentions of clothing. Thus, marital status, per se,

may not be predictive but when coupled with the presence or absence of children in the

household, this combination may be germane. Accordingly, we predict:

H1e. Married Chinese with children are more likely to hold higher intentions to shop

online than married persons with no children or singles (regardless if children are

in the household).

Perceived risk. Perceived risk plays a critical role in consumer decision-making and

behaviors (Mitchell, 1999). This is particularly true with Internet purchases, which involve

activities that are not only technology-intensive but also of an impersonal nature (Bart et al.,

2005; Hsu and Wang, 2008; Yang et al., 2006; Zhou et al., 2007). Prior research has

indicated that the probability of consumers choosing an online marketing channel increases

signicantly if their condence in that channel is high and the perceived risk is low

(Bhatnagar et al., 2000; Black et al., 2002). Within the extant literature, perceived risk has

been conceptualized at several levels of specicity. Some studies have operationalized this

construct in a multidimensional fashion that focuses on different aspects such as privacy

performance, payment, and social risk (e.g. Karson, 2008; Miyazaki and Fernandez, 2001;

Cases, 2002). Park et al. (2004) have taken an intermediate approach and categorized these

risks according to related to product/service (such as functional loss, nancial loss, time loss

and opportunity loss) and those related to online transaction (such as privacy, security, and

nonrepudiation). Conversely, Pavlou (2003) argues that perceived risk in the context of

online shopping is a unidimensional construct. Despite the considerable variance on how to

conceptualize this construct, the empirical literature is more straightforward. In general, the

negative relationship between perceived risk and consumers attitudes toward online

shopping and in turn, their intention to shop online has received widespread empirical

support (e.g. Bhatnagar et al., 2000; Dinev and Hart, 2005; Featherman and Pavlou, 2003;

Jarvenpaa et al., 1999; Joines et al., 2003; Kolsaker et al., 2004; Liang and Jin-Shiang, 1998;

Liao and Cheung, 2001; Liu and Wei, 2003; Molina-Castillo and Lopez-Nicolas, 2007; Park

et al., 2004; Pavlou, 2003; Ruyter et al., 2001). Thus we propose:

H2. Perceived risk negatively inuences Chinese consumers intention to shop online.

Perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness. Based on the comprehensive review by

Cheung et al. (2005), the technology acceptance model (TAM) (Davis, 1989) is one of the

dominant theories underlying the examination of consumer online behavior. TAM was

originally developed to explain and predict computer-usage behavior based on two specic

behavioral beliefs: perceived ease of use (PEU) and perceived usefulness (PU). Perceived

usefulness is the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system would

enhance his or her job performance, and perceived ease of use is the degree to which a

person believes that using a particular system would be free of effort (Davis, 1989. p. 320).

VOL. 7 NO. 3 2013

j

JOURNAL OF ASIA BUSINESS STUDIES

j

PAGE 219

It has since been applied to diverse types of information systems as well as users behavior

on the internet, such as internet users online shopping behavior (e.g. Gefen et al., 2003;

Klopping and McKinney, 2004; Park et al., 2004). The benets identied in the e-commerce

literature relative to PEU include the perceived ease of information search, ease of ordering

(any time, any location) and overall ease of use, while PU encompasses improved search

and buying, increased shopping productivity, money and time saved by shopping online,

and greater product choices available online (Khalifa and Liu, 2007; Park et al., 2004).

In general, PU has been shown to have a signicant inuence on attitude formation and

subsequent behaviors and has received considerable empirical support (e.g. Davis, 1989;

Zhou et al., 2007), whereas the evidence for perceived ease of use has been inconsistent

(Klopping and McKinney, 2004). Based on these conceptualizations and empirical

precedents, we posit:

H3a. Perceived ease of use will positively inuence Chinese consumers likelihood of

shopping online.

H3b. Perceived usefulness will positively inuence Chinese consumers likelihood of

shopping online.

Methodology

Sample size and prole

Data for this study were collected as part of a larger effort to compare the attitudes and

behaviors related to Internet use and online shopping of Chinese consumers with a

benchmark study of US consumers conducted by Pew Internet & American Life Project

(Horrigan, 2008). Some changes (such as income categorization and product categories)

were made to t the Chinese context based on CNNIC Online Shopping Survey (2006). The

questionnaire was translated and back-translated to ensure semantic consistency between

Chinese and English versions (Singh, 1995) prior to pre-testing.

DigitalBiz.com, a Washington DC-based company specializing in online marketing

research, was commissioned for data collection. The survey was conducted on a private

web site administered by the company. The sampling frame included e-mail addresses

collected from major Internet sites in China. Invitations to participate in the research were

sent to 8,000 random addresses. A total of 503 respondents completed the survey,

representing a response rate of 6.5 percent. No incentives or follow-up e-mail reminders

were used to increase participation. Thus, the sample was a product of self-selection and all

the respondents should be considered as Internet users. Data collection lasted about one

week. Respondents were screened to be at least 16 years old. Table I presents the sample

demographics and webgraphics and a comparison of the composition between those who

have made a purchase online with those who have not yet done so. While male respondents

seem to be overrepresented and those under 18 are underrepresented relative to the

population of Chinas as a whole, the sample education and income distributions are in line

with what have been reported about Chinese online customers (CNNIC, 2008a).

Operationalization of variables

Our dependent measure, online shopping intention was operationalized as a formative index

(Diamantopoulos and Winklhofer, 2001) comprising 15 items that were measured using

ve-point Likert scales bounded by very likely and very unlikely. It encompassed a

broad range of product categories and was not specic to using a particular online retailing

venue.

Predictor variables

1. Demographics:

B Gender (H1a) was measured with a single dichotomous item and included as a single

dummy variable in the substantive analysis. Male served as the benchmark.

PAGE 220

j

JOURNAL OF ASIA BUSINESS STUDIES

j

VOL. 7 NO. 3 2013

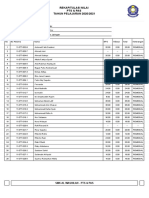

Table I Sample demographics and webgraphics

All (%)

n 503

Online

purchasers (%)

n1 417

Online

non-purchasers (%)

n2 86

Gender

Men 73.6 73.4 74.4

Women 26.4 26.6 25.6

Age

16-17 1.0 .5 3.5

18-24 29.8 29.7 30.2

25-34 50.5 52.3 41.9

35-44 15.5 15.8 14.0

45-54 2.2 0.7 9.3

55-64 1.0 1.0 1.2

65-74

75

Marital status

a

Single without children 54.3 54.2 53.3

Single with children 1.4 0.7 4.7

Married without children 9.7 10.4 7.0

Married with children 34.2 34.7 34.9

Education

Below secondary

Secondary 1.2 0.5 4.7

High School 8.0 6.0 17.4

Junior College 24.7 23.5 30.2

Undergraduate 57.3 59.5 46.5

Graduate and above 8.9 10.6 1.2

Monthly income

under RMB 500 5.4 4.1 11.6

RMB 501 to 1000 5.4 4.6 9.3

RMB 1001 to 2000 19.9 17.5 31.4

RMB 2001 to 3000 18.5 19.2 15.1

RMB 3001 to 4000 17.3 18.5 11.6

RMB 4001 to 5000 10.3 11.0 7.0

RMB 5001 and above 16.7 18.9 5.8

Do not know or refused 2.4 1.9 4.7

No income 4.2 4.3 3.5

Internet usage

Never

Less than once a month 0.4 0.5

1 to 3 times per month 0.6 0.7

1 to 3 times per week 3.0 2.2 7.0

4 to 6 times per week 17.1 16.3 20.9

Once a day or more 78.9 80.3 72.1

Place of internet access

At workplace 23.7 24.2 20.9

At home 63.2 64.0 59.3

At school 8.5 7.9 11.6

Internet cafe 2.4 2.2 3.5

Others 2.2 1.7 4.7

Surng equipment

Desktop computer 73.0 72.2 76.7

Laptop computer 26.2 27.1 22.1

Mobile phone 0.8 0.7 1.2

Note:

a

Missing value for two cases

VOL. 7 NO. 3 2013

j

JOURNAL OF ASIA BUSINESS STUDIES

j

PAGE 221

B Age (H1b) was measured with a single ordinal item where each of the ten response

categories represented a range of ages. The midpoint of the selected range was

included in the substantive analysis.

B Education (H1c) was measured with a single ordinal itemwith six response categories.

For the substantive analysis three of the lowest categories were combined to represent

high school or lower. The resulting 4 categories were represented by three dummy

variables in the substantive analysis and high school or lower served as the

benchmark.

B Income (H1d) was measured with a single ordinal item where seven of the nine

response categories represented an income range, one represented no income, and

the nal category dont know or refused was treated as a missing value. The

midpoint of the indicated range was included in the substantive analysis.

B Marital status (H1e) was operationalized to encompass both marital status and the

presence or absence of children in the household. The four categories were

represented by three dummy variables in the substantive analysis and single without

children served as the benchmark.

2. Perceived risk (H2) was operationalized as a formative index (Diamantopoulos and

Winklhofer, 2001) comprising six items, with the respondent instructed to check all that

apply.

3. Perceived ease of use (H3a) was operationalized as a three-item reective scale and

validated using the procedures recommended by Churchill (1979). The reliability of this

scale is (Cronbach 0:68).

4. Perceived usefulness (H3b) was operationalized as a nine-item reective scale and

validated following the same procedure. The reliability of this scale is (Cronbach 0:88).

Substantive analysis. The hypotheses were tested in a hierarchical fashion using ordinary

least squares (OLS) regression. In the initial run, the main effects of the demographic

variables were assessed. The main effects of the three substantive factors, i.e. perceived

risk, PEU and PU were then added, and the model was re-estimated. The signicant overall

F tests in both runs are indicative that interpretation of the individual regression models and

parameter estimates for the independent variables is warranted. Results are displayed in

Table II.

Table II Regression results (standardized coefcients and t-values shown)

DV: online shopping intention Baseline (demographics) Full (demographics and substantive)

Constant 18.505 * 6.629*

Gender (dummy variable) 0.046 1.057 ns 0.059 1.339***

Age 20.163 23.022* 20.144 22.876*

Education1 (dummy variable) 0.107 1.455*** 0.085 1.247 ns

Education2 (dummy variable) 0.163 2.041** 0.147 1.992**

Education3 (dummy variable) 0.058 0.961 ns 0.041 0.722 ns

Income 0.262 5.371* 0.191 4.143*

Marital and children in home Status1 (dummy

variable) 0.067 1.497*** 0.057 1.376***

Marital and children in home Status2 (dummy

variable) 0.083 1.802** 0.058 1.361***

Marital and children in home Status3 (dummy

variable) 0.129 2.284** 0.089 1.691**

Perceived risk 20.021 20.530 ns

Ease of use 0.017 0.419 ns

Usefulness 0.376 9.149 *

F-value

(df1,df2)

F(9,481)6.675* F(12,478) 12.887*

R

2

(Adjusted R

2

) 0.111 (0.094) 0.244 (0.225)

DR

2

/DF-value DR

2

0.133/DF

(3,478)

6.212*

Notes: Signicance levels (one-tailed test) * p , 0:01; ** p , 0:05; *** p , 0:10; ns not signicant

PAGE 222

j

JOURNAL OF ASIA BUSINESS STUDIES

j

VOL. 7 NO. 3 2013

As we can see from Table II, the addition of the main effect terms relating to the three

substantive variables results in a signicant improvement in the explanatory power of the

models. R

2

showed a signicant improvement from .11 to .24. Table III summarizes the

hypotheses and testing results.

Discussion and managerial implications

Summarizing our results concerning demographics, our hypothesis related to gender (H1a)

was not supported given the marginally signicant parameter estimate, which suggests that

Chinese male and female consumers hold similar online shopping intentions. We did nd a

signicant inverse relationship with regards to age, thereby supporting H1b. H1c was

partially supported in that the dummy variable corresponding to undergraduate degree was

signicant. As expected, we did nd a signicant relationship with regards to income, which

supported H1d. H1e was supported in that the dummy variable corresponding to married

with children was signicant and greater than the other marital status/children in household

categories.

Perceived risk was found to have no signicant inuence on online shopping intentions, thus

H2 was not supported. We found mixed results regarding the two media characteristics.

Perceived ease of use generated a non-signicant parameter estimate, which was contrary

to H3a, whereas perceived usefulness was found to have a signicant positive effect, which

supported H3b.

As summarized above, the results of our study are mostly in accordance with expectations

and contribute to our understanding of the drivers of consumer e-commerce in China. Our

results would be of the most practical interest to e-marketers, both domestic and

international. Our research provides empirical evidence about how consumer

characteristics (i.e. gender, age, income, education, marital status) and medium

characteristics (i.e. perceived risk, ease of use and usefulness) can inuence Chinese

consumers online shopping behavior. We believe that we can all agree on the signicance

and potential of the B2C e-commerce in China. As such, our ndings will be of value to both

domestic and international e-marketers who are trying to inuence consumers online

shopping decisions. Our results will help develop an understanding of what drives Chinese

consumers to shop online, which will, in turn, help e-marketers design e-marketing

strategies that cater to the changing needs and lifestyles of Chinese consumers and

enhance their online shopping experiences and satisfaction.

Table III Summary of hypotheses and testing results

Hypotheses Results

H1a. Chinese male consumers are likely to hold higher online

shopping intentions than their female counterparts

Not supported

H1b. There is an inverse relationship between Chinese consumers

age and their intention to shop online

Supported

H1c. The higher the educational level of Chinese consumers, the more

likely they will intend to shop online

Partially supported

H1d. The higher the income level of Chinese consumers, the more

likely they will shop online

Supported

H1e. Married Chinese with children are more likely to hold higher

intentions to shop online than married persons with no children or

singles (regardless if children are in the household)

Supported

H2. Perceived risk negatively inuences Chinese consumers intention

to shop online

Not supported

H3a. Perceived ease of use will positively inuence Chinese

consumers likelihood of shopping online

Not supported

H3b. Perceived usefulness will positively inuence Chinese

consumers likelihood of shopping online

Supported

VOL. 7 NO. 3 2013

j

JOURNAL OF ASIA BUSINESS STUDIES

j

PAGE 223

Marketers must knowwho their buyers are and what drives themin order to develop the most

actionable marketing plans and strategies. Previous research has delineated the effects of

consumer demographics in the buying process. Our results indicate that Chinese

consumers age, education, income and marital status are signicant predictors of their

Internet purchase intention, echoing the ndings from most of the existing literature in the

area. Several market research reports have found that young and educated consumer

segments with higher income level are mainly the early adopters of online shopping in China

(Lee, 2009; Rein, 2008). The nding that gender is not a signicant predictor of Chinese

consumers online shopping intention appears to be at odds with what have been

documented in the extant literature (e.g. Citrin et al., 2003; Garbarino and Strahilevitz, 2004;

Rogers and Harris, 2003; Swaminathan et al., 1999; Yoo-Kyoung and Bailey, 2008). There

may be a simple reason for this the rapid growth of Internet use and online shopping in

China may have evened out the gender aspect of the typical shopper, something certainly

worth further investigation. Meanwhile, because of the over-representation of the male

respondents in our sample, to better investigate the effects of gender, we conducted a post

hoc analysis, where we split the sample by gender (n1 361 for the male subgroup and

n2 128 for the female subgroup) and reran the models using the same variable set except

the gender dummy variable. Interesting results emerged where some regression

coefcients are signicantly different across the two subgroups. According to the post

hoc analysis results, we found negative effect of age is more pronounced in women than in

men (t 1:81, p , 0:1); effect of highest education level is positive for men, whereas the

opposite is true for women (t 1:80, p , 0:1); and effect of risk level is negative for men,

whereas the opposite is true for women (t 21:95, p , 0:05).

No doubt, consideration of individual differences in explaining consumers online buying

intention could provide a better understanding of users adoption of the Internet as a

shopping and transaction channel as well as enhance an e-tailers market targeting and

segmentation effectiveness.

An interesting nding of the study is the insignicance of perceived risk as predictor of

Chinese consumers online shopping intentions. Although the majority of the Chinese

respondents expressed their top concerns as product not being able to live up to

expectations, disputes being difcult to resolve, unreliable customer service and making

online payment, such concerns do not seem to affect their online shopping intention. This

leads us to infer that security and privacy concerns are becomingless important in predicting

Chinese consumers online shopping intention, especially with rapid advancement of

information technologies and increasingly improved regulation/legislation on e-commerce in

China. However, this by no means indicates that e-marketers would not benet fromadopting

and implementing buyer-friendly online security and privacy protection measures.

Contrary to our expectation, perceived ease of use was not found to be a predictor of

Chinese consumers online shopping intention. Knowledge of the reality of Chinas internet

and e-tailing industry may help explain this nding. Although broadband Internet access

have gained a wide popularity in China (91 percent, 94 percent and 98 percent for 2008,

2009 and 2010 respectively) (CNNIC, 2008b, 2009, 2010), download speed remains far

behind that of developed countries (CNNIC, 2010) and the data transfer rate further slows

down during peak hours because broadband width is shared (Lee, 2009). The poor

nationwide distribution networks and the lack of a safe and efcient online payment

mechanism are signicant hurdles that hinder Internet purchases in China. In addition,

despite the growing popularity, credit card usage and transaction volume are still very low in

China, compared to those of developed economies (Hunkar, 2009). These local conditions

may greatly reduce the convenience and, in turn, ease of use of online shopping among

Chinese consumers. However, along with the increased affordability, increasingly more

Chinese are searching on the Internet. Product information made available on the Internet

via comparison sites, chat rooms, blogs or social media networks may be perceived as a

great advantage. There is an old Chinese saying never make a purchase until you have

compared three shops. Such comparison convenience may be more appreciated by

Chinese consumers. Further, source credibility greatly affects Chinese consumers search

PAGE 224

j

JOURNAL OF ASIA BUSINESS STUDIES

j

VOL. 7 NO. 3 2013

activity and word-of-mouth (WOM) is greatly valued due to their group orientation.

Information shared by other consumers can be very inuential because it is not controlled by

the marketers and is thus seen as more credible. Therefore, although Chinese consumers

may not perceive online shopping to be easy, they still exhibit favorable attitudes toward

online shopping because of other advantages associated with it such as time-saving, lower

price, and wide selection (Gong and Maddox, 2010). This consequently facilitates their

online shopping intentions.

Perceived usefulness showed a signicant impact on Chinese consumers online shopping

intentions. This is in line with what has been documented in the literature and reects the

general utilitarian nature of online consumers (Jarvenpaa and Todd, 1997). The nding

suggests that e-marketers should incorporate features that can greatly enhance online

shopping efciency, for example, a search mechanism that can not only provide extensive

relevant information but also facilitate product comparison and help users make their best

decisions inamost efcient way. Of equal importanceis therealization that shoppingintention

is not equivalent to actual purchase. While more web site visitors have become more

comfortable andexperiencedshoppingonline, a recent study revealedthat about 50 percent

of Chinese online consumers abandon their shopping cart before purchase (China Business

Daily, 2008), suggesting a problem for e-marketers who prefer buyers but not browsers. As

such, it is important for the e-tailers to identify and address the drivers of cart abandonment

and nd innovative ways to bring consumers back and encourage future transactions. Cart

abandonment highlights the challenge for e-tailors to understandonline consumers potential

frustration and unpreparedness to make a purchase as well as the opportunity for them to

recover lost sales by clearing the path to purchase, keeping a tab on competitors prices,

clarifyingshippingcosts anddelivery times upfront, avoidingout-of-stock scenario as well as

pinning down the simplest checkout procedure (Mulpuru et al., 2010).

Limitations and suggestions for future research

Several limitations of this study shouldbe mentioned. First, despitethefact that weconducted

a nationwide survey, males and older consumers are over-represented in our sample,

compared to general online customers prole depicted by CNNIC (2008a). Also, the

response rate can be improved by providing incentives and/or sending follow-up e-mails. As

such, the Chinese sample may not be representative of the Chinese online shopping

population as a whole. Second, we used consumers online shopping intention as the

dependent variable in the study instead of their actual online purchase amount or frequency.

The self-report nature of purchase intention may be a potential bias. Third, only two major

categories of determinants of consumer online behavior, namely consumer characteristics

and medium characteristics were included in our conceptual model. Taking these into

consideration, the results are to be interpreted in light of the limitations outlined here.

Future research should use Chinese consumers actual online purchases as the dependent

variable and more revealing results regarding consumer e-commerce in China may come to

light. Future research should also explore the effects of product characteristics, merchants

and intermediate characteristics and environmental inuences in online shopping behavior

and enhance the predictive power of the proposed model. In terms of research

methodology, other techniques such as web analytics can be considered and utilized in

future research to better understand consumers web usage. Researchers should also start

to investigate additional topics that may be of great interest to e-marketers in China. For

example, how will customer service and return policy affect Chinese consumers online

shopping intentions and subsequent purchase behavior? Knowledge in this regard will help

e-marketers understand the role of these factors in the formation of expectations and their

impact on customer satisfaction and retention. Social networking web sites are perceived by

Chinese online users as good places for opinion and information sharing and allow them to

make better shopping decisions (CNNIC, 2010). Insights about the potential of

social-shopping sites in converting Internet users into online buyers in China should

help e-marketers design more effective viral marketing and e-WOM marketing strategies on

these web sites in generating desired outcomes.

VOL. 7 NO. 3 2013

j

JOURNAL OF ASIA BUSINESS STUDIES

j

PAGE 225

Note

1. Throughout this paper we use the terms netizens and internet users interchangeably.

References

Ajzen, I. and Fishbein, M. (1980), Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior, Prentice Hall,

Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Alreck, P. and Settle, R.B. (2002), Gender effects on internet, catalogue and store shopping, Journal of

Database Marketing, Vol. 9 No. 2, pp. 150-162.

Bart, Y., Shankar, V., Sultan, F. and Urban, G.L. (2005), Are the drivers and role of online trust the same

for all web sites and consumers? A large-scale exploratory empirical study, Journal of Marketing,

Vol. 69 No. 4, pp. 133-153.

Bellman, S., Lohse, G.L. and Johnson, E.J. (1999), Predictors of online buying behavior,

Communications of the ACM, Vol. 42 No. 12, pp. 32-38.

Bhatnagar, A., Misra, S. and Rao, H.R. (2000), On risk, convenience, and internet shopping behavior,

Communications of ACM, Vol. 43 No. 11, pp. 98-105.

Black, N.J., Lockett, A., Ennew, C., Winklhofer, H. and McKechnie, S. (2002), Modeling consumer

choice of distribution channels: an illustration from nancial services, International Journal of Bank

Marketing, Vol. 20 No. 4, pp. 161-173.

Cases, A. (2002), Perceived risk and risk-reduction in internet shopping, The International Review of

Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, Vol. 12 No. 4, pp. 375-394.

Chang, M.K., Cheung, W. and Lai, V.S. (2005), Literature derived reference models for the adoption of

online shopping, Information & Management, Vol. 42 No. 4, pp. 543-559.

Chen, L., Gillensonb, M.L. and Sherrellb, D.L. (2002), Enticing online consumers: an extended

technology acceptance perspective, Information & Management, Vol. 39 No. 8, pp. 705-719.

Cheung, C., Chan, G. and Limayem, M. (2005), A critical reviewof online consumer behavior: empirical

research, Journal of Electronic Commerce in Organizations, Vol. 3 No. 4, pp. 1-19.

China Business Daily (2008), High abandon rate of online shopping cart, China Business Daily,

available at http://china-business-daily.blogspot.com/2008/12/high-abandon-rate-of-online-shopping.

html (9 December) (accessed 3 September 2011).

Citrin, A.V., Stem, D.E. Jr, Spangenberg, E.R. and Clark, M.J. (2003), Consumer need for tactile input:

an internet retailing challenge, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 56 No. 11, pp. 915-923.

CNNIC (2006), China Online Shopping Market Survey Report 2006, available at: www.cnnic.cn/

uploadles/pdf/2006/5/26/141308.pdf (accessed 7 June 2010).

CNNIC (2008a), Statistic survey report on the online shopping market in China, available at: www.

cnnic.net.cn/index/0E/manual/91/index.htm (accessed 24 June 2010).

CNNIC(2008b), Statistic report on internet development in China January, available at: www.cnnic.cn/

uploadles/pdf/2008/2/29/104126.pdf (accessed 13 June 2010).

CNNIC (2009), Statistic report on internet development in China January, available at: www.cnnic.cn/

uploadles/pdf/2009/3/23/153540.pdf (accessed 13 June 2010).

CNNIC (2010), Statistic report on internet development in China January available at: www.cnnic.cn/

uploadles/pdf/2010/3/15/142705.pdf (accessed 13 June 2010).

Churchill, G.A. (1979), A pardigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs, Journal of

Marketing Research, Vol. 16 No. 1, pp. 64-73.

Davis, F.D. (1989), Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information

technology, MIS Quarterly, Vol. 13 No. 3, pp. 319-339.

Dholakis, R.R. and Chiang, K.P. (2003), Shoppers in cyberspace: are they fromVenus or Mars or does it

matter?, Journal of Consumer Psychology, Vol. 13 Nos 1/2, pp. 171-176.

PAGE 226

j

JOURNAL OF ASIA BUSINESS STUDIES

j

VOL. 7 NO. 3 2013

Diamantopoulos, A. and Winklhofer, H.M. (2001), Index construction with formative indicators: an

alternative to scale development, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 38 No. 2, pp. 269-277.

Dickerson, M.D. and Gentry, J.W. (1983), Characteristics of adopters and non-adopters of home

computer, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 10, September, pp. 225-235.

Dinev, T. and Hart, P. (2005), Internet privacy concerns and social awareness as determinants of

intention to transact, International Journal of Electronic Commerce, Vol. 10 No. 2, pp. 7-29.

Donthu, N. and Garcia, A. (1999), The internet shopper, Journal of Advertising Research, Vol. 39 No. 3,

pp. 52-58.

Doolin, B., Dillon, S., Thompson, F. and Corner, J.L. (2005), Perceived risk, the internet shopping

experience and online purchasing behavior: a New Zealand perspective, Journal of Global Information

Management, Vol. 13 No. 2, pp. 66-88.

Eastin, M.S. (2002), Diffusion of e-commerce: an analysis of the adoption of four e-commerce

activities, Telematics and Informatics, Vol. 19 No. 3, pp. 251-267.

Fallows, D. (2005), How men and women use the internet, Pew Internet and American Life Project,

available at: www.pewinternet.org/,/media//Files/Reports/2005/PIP_Women_and_Men_online.pdf.pdf

(accessed 30 April 2010).

Featherman, M. and Pavlou, P.A. (2003), Predicting e-services adoption: a perceived risk facets

perspective, International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, Vol. 59 No. 4, pp. 451-474.

Fishbein, M. and Ajzen, I. (1975), Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behaviour: An Introduction to Theory and

Research, Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Reading, MA.

Garbarino, E. and Strahilevitz, M. (2004), Gender differences in the perceived risk of buying online and

the effects of receiving a site recommendation, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 57 No. 7,

pp. 768-775.

Gatignon, H. and Robertson, T.S. (1991), Innovative decision processes, in Robertson, T.S. and

Kassarjian, H.H. (Eds), Handbook of Consumer Behavior, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Gefen, D., Karahanna, E. and Straub, D.W. (2003), Trust and TAM in online shopping: An integrated

model, MIS Quarterly, Vol. 27 No. 1, pp. 51-90.

Gong, W. and Li, Z.G. (2008), Mobile youth in China: a cultural perspective and marketing

implications, International Journal of Electronic Business, Vol. 6 No. 3, pp. 261-281.

Gong, W. and Maddox, L. (2010), Online buying decision in China, Journal of American Academy of

Business, Cambridge, Vol. 17 No. 1, pp. 43-50.

Gong, W., Li, Z.G. and Li, T. (2004), Marketing to Chinese youths: a cultural transformation

perspective, Business Horizons, Vol. 47 No. 6, pp. 41-50.

Ha, H-Y. (2006), An integrative model of consumer satisfaction in the context of e-services,

International Journal of Consumer Studies, Vol. 30 No. 2, pp. 137-149.

Horrigan, J.B. (2008), Online shopping, Pew Internet & American Life Project, available at: www.

pewinternet.org/Press-Releases/2008/Online-Shopping.aspx (accessed 13 June 2010).

Hsu, L-C. and Wang, C-H. (2008), A study of e-trust in online auctions, Journal of Electronic

Commerce Research, Vol. 9 No. 4, pp. 310-321.

Hui, T-K. and Wan, D. (2007), Factors affecting internet shopping behavior in Singapore: gender and

educational issues, International Journal of Consumer Studies, Vol. 31 No. 3, pp. 310-316.

Hunkar, D. (2009), Growth in credit card usage in India and China, Seeking Alpha, 26 November,

available at: http://seekingalpha.com/article/175425-growth-in-credit-card-usage-in-india-and-china

(accessed 18 July 2011).

IResearch (2009), Online purchase sales reached RMB1,600 per person in 2008. C2Cremains the best

choice, available at: www.iresearch.com.cn/html/Consulting/Online_Shopping/DetailNews_id_90683.

html (accessed 5 June 2013).

VOL. 7 NO. 3 2013

j

JOURNAL OF ASIA BUSINESS STUDIES

j

PAGE 227

Jarvenpaa, S.L. and Todd, P. (1997), Consumer reactions to electronic shopping on the world wide

web, International Journal of Electronic Commerce, Vol. 1 No. 2, pp. 59-88.

Jarvenpaa, S.L., Tractinsky, N. and Vitale, M. (1999), Consumer trust in an internet store, Information

Technology and Management, Vol. 1 No. 12, pp. 45-71.

Jayawardhena, C., Wright, L.T. and Dennis, C. (2007), Consumer online: intentions, orientations and

segmentation, International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, Vol. 35 No. 6, pp. 515-526.

Joines, J., Scherer, C. and Scheufele, D. (2003), Exploring motivations for consumer web use and their

implications for e-commerce, Journal of Consumer Marketing, Vol. 20 No. 2, pp. 90-109.

Karson, E.J. (2008), Exploring consumers privacy concerns: does data from three years of student

samples support the conventional wisdom?, International Journal of Internet Marketing and

Advertising, Vol. 4 No. 4, pp. 362-381.

Khalifa, M. and Liu, V. (2007), Online consumer retention: contingent effects of online shopping habit

and online shopping experience, European Journal of Information Systems, Vol. 16, pp. 780-792.

Kiiski, S. and Pohjola, M. (2002), Cross-country diffusion of the internet, Information Economics and

Policy, Vol. 14 No. 2, pp. 297-310.

Kim, E.Y. and Kim, Y.K. (2004), Predicting online purchase intentions for clothing products, European

Journal of Marketing, Vol. 38 No. 7, pp. 883-897.

Klopping, I.M. and McKinney, E. (2004), Extending the technology acceptance model and the

task-technology t model to consumer e-commerce , Information Technology, Learning, and

Performance Journal, Vol. 22 No. 1, pp. 35-48.

Kolsaker, A., Lee-Kelley, L. and Choy, P.C. (2004), The reluctant Hong Kong consumer: Purchasing

travel online, International Journal of Consumer Studies, Vol. 28 No. 3, pp. 295-304.

Lee, H-T. (2009), Online-Shopping Market in China Adventurous Kingdom for Foreign SME, CBC

Marketing Research Shanghai Ofce.

Li, D., Browne, G.J. and Wetherbe, J.C. (2006), Why do internet users stick with a specic web site? A

relationship perspective, International Journal of Electronics Commerce, Vol. 10 No. 4, pp. 105-141.

Li, H., Kuo, C. and Russell, M.G. (1999), The impact of perceived channel utilities, shopping

orientations, and demographics on the consumers online buying behavior , Journal of

Computer-Mediated Communication, Vol. 5 No. 2, available at: http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol5/issue2/

hairong.html (accessed 3 May 2010).

Liang, T-P. and Jin-Shiang, H. (1998), An empirical study on consumer acceptance of products in

electronic markets: a transaction cost model, Decision Support Systems, Vol. 24 No. 1, pp. 29-43.

Liao, Z. and Cheung, M.T. (2001), Internet-based e-shopping and consumer attitudes: an empirical

study, Information and Management, Vol. 38 No. 5, pp. 299-306.

Liebermann, Y. and Stashevsky, S. (2009), Determinants of online shopping: examination of an

early-stage online market, Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, Vol. 26 No. 4, pp. 316-331.

Liu, X. and Wei, K.K. (2003), An empirical study of product differences in consumers e-commerce

adoption behavior, Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, Vol. 2 No. 3, pp. 229-239.

Mahmood, M.A., Bagchi, K. and Ford, T.C. (2004), On-Line shopping behavior: cross-country empirical

research, International Journal of Electronic Commerce, Vol. 9 No. 1, pp. 9-30.

Massad, N., Heckman, R. and Crowston, K. (2006), Customer satisfaction with electronic service

encounters, International Journal of Electronic Commerce, Vol. 10 No. 4, pp. 73-104.

Mitchell, V.W. (1999), Consumer perceived risk: conceptulisation and models, European Journal of

Marketing, Vol. 33 Nos 1/2, pp. 163-195.

Miyazaki, A.D. and Fernandez, A. (2001), Consumer perceptions of privacy and security risks for online

shopping, The Journal of Consumer Affairs, Vol. 35 No. 1, pp. 27-44.

Molina-Castillo, F-J. and Lopez-Nicolas, C. (2007), Innovative products on the internet: the role of trust

and perceived risk, International Journal of Internet Marketing and Advertising, Vol. 4 No. 1, pp. 53-71.

PAGE 228

j

JOURNAL OF ASIA BUSINESS STUDIES

j

VOL. 7 NO. 3 2013

Mulpuru, S., Hult, P., Evans, P.F. and McGrowan, B. (2010), Understanding shopping cart

abandonment, Forrester Research, available at: www.forrester.com/rb/Research/understanding_

shopping_cart_abandonment/q/id/56827/t/2 (accessed 2 September 2011).

Murdock, G.W. and Franz, L. (1983), Habit and perceived risk as factors in the resistance to the use of

ATMs, Journal of Retail Banking, Vol. 2, pp. 20-29.

Park, C. and Kim, Y. (2006), The effect of information satisfaction and relational benet on consumers

online shopping site commitments, Journal of Electronic Commerce in Organizations, Vol. 4 No. 1,

pp. 70-91.

Park, J., Lee, D. and Ahn, J. (2004), Risk-focused e-commerce adoption model: a cross-country

study, Journal of Global Information Technology Management, Vol. 7 No. 2, pp. 6-30.

Pavlou, P.A. (2003), Consumer acceptance of electronic commerce: integrating trust and risk with the

technology acceptance model, International Journal of Electronic Commerce, Vol. 7 No. 3, pp. 101-134.

Raven, P.V., Huang, X. and Kim, B.B. (2007), E-business in developing countries: a comparison of

China and India, International Journal of E-Business Research, Vol. 3 No. 1, pp. 91-110.

Rein, S. (2008), In China, online shopping soars, Forbes.com, 6 June.

Rogers, E.M. (1995), Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed., Free Press, New York, NY.

Rogers, S. and Harris, M.A. (2003), Gender and e-commerce: an exploratory study, Journal of

Advertising Research, Vol. 43 No. 3, pp. 322-329.

Rohm, A.J. and Swaminathan, V. (2004), A typology of online shoppers based on shopping

orientations, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 57 No. 7, pp. 748-758.

Ruyter, K., Wetzels, M. and Kleijnen, M. (2001), Customer adoption of e-service: an experimental

study, International Journal of Service Industry Management, Vol. 12 No. 2, pp. 184-208.

Shanghai Business Review (2010), Click to add to cart, Shanghai Business Review, March.

Shehryar, O. (2008), The effect of buyers gender, risk-proneness, and time remaining in an internet

auction on the decision to bid or buy-it-now, Journal of Product & Brand Management, Vol. 17 No. 5,

pp. 356-365.

Singh, J. (1995), Measurement issues in cross-national research, Journal of International Business

Studies, Vol. 26 No. 3, pp. 597-619.

Stafford, T.F., Turan, A. and Raisinghani, M.S. (2004), International and cross-cultural inuences on

online shopping behavior, Journal of Global Information Technology Management, Vol. 7 No. 2,

pp. 70-87.

Stoneman, P. (1983), The Economic Analysis of Technological Change, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Susskind, A. (2004), Electronic commerce and world wide web apprehensiveness: an examination of

consumers perceptions of the world wide web, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Vol. 9

No. 3, available at: http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol9/issue3/susskind.html (accessed 3 May 2010).

Swaminathan, V., Lepkowska-White, E. and Rao, B.P. (1999), Browsers or buyers in cyberspace? An

investigation of factors inuencing electronic exchange , Journal of Computer-Mediated

Communication, Vol. 5 No. 2, available at: http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol5/issue2/swaminathan.htm

(accessed 3 May 2010).

Swinyard, W.R. and Smith, S.M. (2003), Why people (dont) shop online: a lifestyle study of the internet

consumer, Psychology and Marketing, Vol. 20 No. 7, pp. 567-597.

van Slyke, C., Comunale, C.L. and Belanger, F. (2002), Gender differences in perceptions of

web-based shopping, Communications of the ACM, Vol. 45 No. 7, pp. 82-86.

Weng, V. and Lee, C.H. (2009), Current status and future development potential of Chinas online

shopping market, available at: http://mic.iii.org.tw/english/Store/en_3_mic_store_1_2_1.asp?doc_

sqno 7133 (accessed 29 March 2010).

Yang, S-C., Hung, W-C., Sung, K. and Farn, C-K. (2006), Investigating initial trust toward e-tailers from

the elaboration likelihood model perspective, Psychology & Marketing, Vol. 23 No. 5, pp. 429-445.

VOL. 7 NO. 3 2013

j

JOURNAL OF ASIA BUSINESS STUDIES

j

PAGE 229

Yoo-Kyoung, S. and Bailey, L. (2008), The inuence of college students shopping orientations and

gender differences on online information searches and purchase behaviors, International Journal of

Consumer Studies, Vol. 32 No. 2, pp. 113-121.

Zhao, A.L., Hanmer-Lloyd, S., Ward, P. and Goode, M.M.H. (2008), Perceived risk and Chinese

consumers internet banking services adoption, International Journal of Bank Marketing, Vol. 26 No. 7,

pp. 505-525.

Zhou, L., Dai, L. and Zhang, D. (2007), Online shopping acceptance model a critical survey of

consumer factors in online shopping, Journal of Electronic Consumer Research, Vol. 8 No. 1, pp. 41-62.

Further reading

Ajzen, I. (1991), The theory of planned behavior, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision

Process, Vol. 50 No. 2, pp. 179-211.

Arnold, M.J. and Reynolds, K.E. (2003), Hedonic shopping motivations, Journal of Retailing, Vol. 79

No. 2, pp. 77-95.

Shankar, V., Smith, A.K. and Rangaswamy, A. (2003), Customer satisfaction and loyalty in online and

ofine environment, International Journal of Research in Marketing, Vol. 20 No. 2, pp. 153-175.

van der Heijden, H. (2003), Factors inuencing the usage of websites: the case of a generic portal in

The Netherlands, Information & Management, Vol. 40 No. 6, pp. 541-549.

Corresponding author

Wen Gong can be contacted at: gong.gw@gmail.com

PAGE 230

j

JOURNAL OF ASIA BUSINESS STUDIES

j

VOL. 7 NO. 3 2013

To purchase reprints of this article please e-mail: reprints@emeraldinsight.com

Or visit our web site for further details: www.emeraldinsight.com/reprints

Вам также может понравиться

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Thurlow 1989Документ23 страницыThurlow 1989Linda PertiwiОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5795)

- Online Diagnostic Assessment in Support of Personalized Teaching and Learning: The Edia SystemДокумент14 страницOnline Diagnostic Assessment in Support of Personalized Teaching and Learning: The Edia SystemLinda PertiwiОценок пока нет

- Knoch 2009Документ30 страницKnoch 2009Linda PertiwiОценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Contextual Factors That Sustain Innovative Pedagogical Practice Using Technology An International StudyДокумент17 страницContextual Factors That Sustain Innovative Pedagogical Practice Using Technology An International StudyLinda PertiwiОценок пока нет

- Diagnostic Feedback in Language AssessmentДокумент32 страницыDiagnostic Feedback in Language AssessmentLinda PertiwiОценок пока нет

- Peterson 2008Документ13 страницPeterson 2008Linda PertiwiОценок пока нет

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Baird 2013Документ4 страницыBaird 2013Linda PertiwiОценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- 05-116-Hyejin ParkДокумент23 страницы05-116-Hyejin ParkLinda PertiwiОценок пока нет

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Is It Safe? Social, Interpersonal, and Human Effects of Peer Assessment: A Review and Future DirectionsДокумент35 страницIs It Safe? Social, Interpersonal, and Human Effects of Peer Assessment: A Review and Future DirectionsLinda PertiwiОценок пока нет

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- BrownДокумент19 страницBrownLinda PertiwiОценок пока нет

- Mostafa 2013Документ19 страницMostafa 2013Linda PertiwiОценок пока нет

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- Brown 2011Документ20 страницBrown 2011Linda PertiwiОценок пока нет

- Analisis Kebijakan PPDB Zonasi Terhadap Prilaku Siswa SMP D YogyakartaДокумент10 страницAnalisis Kebijakan PPDB Zonasi Terhadap Prilaku Siswa SMP D YogyakartaLinda PertiwiОценок пока нет

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Perkalian 1-20Документ3 страницыPerkalian 1-20Linda PertiwiОценок пока нет

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- 02 - Jale Aldemir & Hengameh Kermani (2017) - Integrated STEM CurriculumДокумент14 страниц02 - Jale Aldemir & Hengameh Kermani (2017) - Integrated STEM CurriculumLinda PertiwiОценок пока нет

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Tzeng2007 PDFДокумент17 страницTzeng2007 PDFLinda PertiwiОценок пока нет

- Information & Management: Ching-Wen ChenДокумент8 страницInformation & Management: Ching-Wen ChenLinda PertiwiОценок пока нет

- Rekapitulasi Nilai Pts & Pas TAHUN PELAJARAN 2020/2021Документ2 страницыRekapitulasi Nilai Pts & Pas TAHUN PELAJARAN 2020/2021Linda PertiwiОценок пока нет

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Perkalian 1-20Документ3 страницыPerkalian 1-20Linda PertiwiОценок пока нет

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Sum Bal 2017Документ31 страницаSum Bal 2017Linda PertiwiОценок пока нет

- Leveraging The Capabilities of Service-Oriented Decision Support Systems Putting Analytics and Big Data in CloudДокумент10 страницLeveraging The Capabilities of Service-Oriented Decision Support Systems Putting Analytics and Big Data in CloudLinda PertiwiОценок пока нет

- Aydin & Tasci (2005)Документ14 страницAydin & Tasci (2005)brigiett4Оценок пока нет

- Zachman EAF TutorialДокумент12 страницZachman EAF TutorialLinda PertiwiОценок пока нет

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Yeastmine-An Integrated Data Warehouse For Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Data As A Multipurpose Tool-KitДокумент9 страницYeastmine-An Integrated Data Warehouse For Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Data As A Multipurpose Tool-KitLinda PertiwiОценок пока нет

- Project Management Assignment - 01: Pranav Dosjah 2016DA01004Документ15 страницProject Management Assignment - 01: Pranav Dosjah 2016DA01004Savita Wadhawan100% (1)

- Test Bank For Marketing 5th Edition Dhruv Grewal Michael Levy Shirley LichtiДокумент24 страницыTest Bank For Marketing 5th Edition Dhruv Grewal Michael Levy Shirley Lichtiangelascottaxgeqwcnmy100% (39)

- Chapter 1 The Revolution Is Just Beginning: E-Commerce 2019: Business. Technology. Society., 15e (Laudon/Traver)Документ21 страницаChapter 1 The Revolution Is Just Beginning: E-Commerce 2019: Business. Technology. Society., 15e (Laudon/Traver)이지유(인문과학대학 기독교학과)Оценок пока нет

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Cloud Computing of E-Commerce: Technical Seminar OnДокумент17 страницCloud Computing of E-Commerce: Technical Seminar OnPooja PОценок пока нет

- Chap 9 QuizДокумент4 страницыChap 9 QuizPaaforiОценок пока нет

- E-Commerce Website For Retailers: WWW - Export.gov Teams-Waterfall-Vs-Agile/ Ll-Vs-Agile-MethodologyДокумент12 страницE-Commerce Website For Retailers: WWW - Export.gov Teams-Waterfall-Vs-Agile/ Ll-Vs-Agile-Methodologya-_gОценок пока нет

- 1641-Article Text-4505-1-10-20220521Документ9 страниц1641-Article Text-4505-1-10-20220521Thu Le MinhОценок пока нет

- A Study On Amazon CompanyДокумент18 страницA Study On Amazon CompanyVijay KumarОценок пока нет

- B2B and C2CДокумент10 страницB2B and C2CchrisОценок пока нет

- Accounting & Finance Under The University of Calcutta) : P R OJE C T R EP ORTДокумент47 страницAccounting & Finance Under The University of Calcutta) : P R OJE C T R EP ORTOcto ManОценок пока нет

- Strategic Audit of Ebay, Inc.Документ14 страницStrategic Audit of Ebay, Inc.Hady AbboudОценок пока нет

- K L-Final Comm 223 NotesДокумент21 страницаK L-Final Comm 223 NotesGeorgiana StateОценок пока нет

- Chapter 6 ERPДокумент63 страницыChapter 6 ERPFlash XОценок пока нет

- Electronic Commerce Systems: IT Applications For Digital OrganizationsДокумент21 страницаElectronic Commerce Systems: IT Applications For Digital OrganizationsAkshay MohanОценок пока нет

- E-Business: The Revolution Is Just BeginningДокумент66 страницE-Business: The Revolution Is Just BeginningbarundudeboyОценок пока нет

- A Literature Review On Purchase Intention Factors in E-CommerceДокумент14 страницA Literature Review On Purchase Intention Factors in E-CommerceFuadОценок пока нет

- Mis Unit-7Документ36 страницMis Unit-7Kunal KambleОценок пока нет

- EssayДокумент2 страницыEssayMariecon MonteroОценок пока нет

- 12th Computer Marvel (Eng) (GSEBMaterial - Com)Документ154 страницы12th Computer Marvel (Eng) (GSEBMaterial - Com)37-Nand S Patel100% (2)

- Alibaba CaseДокумент7 страницAlibaba Casevania gabriellaОценок пока нет

- ADL 75 E Commerce V2Документ5 страницADL 75 E Commerce V2solvedcareОценок пока нет

- Edit Shopee (E-Commerce) MISДокумент22 страницыEdit Shopee (E-Commerce) MISRabiatul AdawiyahОценок пока нет

- Ecommerce Ch3Документ35 страницEcommerce Ch3hamba AbebeОценок пока нет

- E Commerce in IndiaДокумент19 страницE Commerce in IndiaSamyaОценок пока нет

- CH 3Документ7 страницCH 3AbdirahmanОценок пока нет

- Vstavek PKP 1Документ248 страницVstavek PKP 1Goran JurosevicОценок пока нет

- Foundational Concepts In: Chapter Two MISДокумент9 страницFoundational Concepts In: Chapter Two MISHayelom Tadesse GebreОценок пока нет

- Alibaba's Strategic DriftДокумент9 страницAlibaba's Strategic Driftun zghibiОценок пока нет

- KnowMore Test TasksДокумент6 страницKnowMore Test TasksMonnu montoОценок пока нет

- Minor Project ReportДокумент16 страницMinor Project ReportManav AroraОценок пока нет