Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Gracia - An Exploration

Загружено:

LadyromancerWattpad0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

20 просмотров16 страницhistory

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документhistory

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

20 просмотров16 страницGracia - An Exploration

Загружено:

LadyromancerWattpadhistory

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 16

An exploration of student failure on an

undergraduate accounting programme of study

LOUI SE GRACI A* and ELLI S JENKI NS

University of Glamorgan, S Wales, UK

Received: July 2001

Revised: October 2001

Accepted: November 2001

Abstract

Academic failure creates nancial and emotional issues for students, with associated resource and

performance implications for higher education institutions. The literature reveals that much of the

work on student performance is quantitative, restricting understanding of the deeper feelings and

perceptions of students towards their studies. This paper explores undergraduate student perform-

ance from an experiential perspective, recognising the complexity and subjectivity of academic

performance. Findings appear to highlight: the negative focus of reasoning underlying the choice of

study; the impact of affect; the importance of the role of the tutor; the tutor expectations gap; levels

of control and personal responsibility for learning; and patterns of participation as possible

signicant and important factors in understanding academic performance. Finally, the implications

of the ndings are discussed and further research outlined in terms of developing a predictive model

that could offer early identication of students who are susceptible to academic failure and

establishing appropriate, proactive support strategies for such students.

Keywords: Academic performance, accounting education, experiential perspective, semistructured

interviews, student reections on failure

Introduction

Academic success is of primary importance to students, their teachers and the higher

educational institutions (HEIs) at which they study. Academic failure creates a major

nancial and emotional burden for students as they struggle to come to terms with failure

in both a personal and economic sense. It also has resource and performance implications

for the HEIs, the relative performances of which are monitored and published in annual

league tables. Academic failure impacts upon degree results and retention rates, both of

which are used as key performance indicators to evaluate HEIs. Moreover, the problems of

student failure are likely to be exacerbated by recent and current Government initiatives to

increase participation rates and widen access, whilst at the same time reducing the

nancial support offered to students via grants.

This paper explores undergraduate academic performance through student experience. It

seeks to understand the meaning and emphasis that students place on different aspects of

their learning experience and hence provides an understanding of how experiential factors

inuence academic performance on the second and nal years of study. In addition, by

* Address for correspondence: Mrs. Louise Gracia, Business School, University of Glamorgan, Llantwit Road,

Treforest, S Wales, CF37 1DL, UK. E-mail lgracia@glam.ac.u k

Accounting Education 11 (1), 93107 (2002)

Accounting Education

ISSN 09639284 print/ISSN 14684489 online 2002 Taylor & Francis Ltd

http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals

DOI: 10.1080/0963928021015329 0

adopting a qualitative approach, it attempts to address the decit of deeper understanding

of student experience on academic performance within the existing accounting education

literature.

Literature review

The research that has attempted to identify and analyse the factors that explain differences

in academic performance tends to be quantitative in nature and presents a variety of

conicting and contradictory conclusions. The impact of prior accounting knowledge on

academic performance in rst year university accounting studies continues to be one of the

most widely researched factors. Despite its frequency of study no consensus exists on its

inuence or otherwise on academic performance.

Baldwin and Howe (1982) found no difference between the overall performance of

students irrespective of their level of prior accounting knowledge. Bergin (1983) conrms

this nding, concluding that overall course performance is unrelated to prior high school

accounting exposure. This view is further supported by Schroeder (1986), who also found

no difference in the overall course performance of students with prior high school

accounting exposure and those without. Bartlett et al. (1992,1993) carried out a

longitudinal study of students specializing in accounting over the period 19891992. They

carried out tests of the relationship between academic performance and a large range of

explanatory variables including age, gender, region, prior study and educational attributes.

They concur that the prior study of accounting has no signicant effect on academic

performance, concluding that only the prior study of economics has a signicant effect on

performance.

Further studies offer different ndings. Studies by Mitchell (1985,1988) found that

students with prior accounting or A level mathematics perform better statistically, in the

computational and quantitative aspects of courses. Gul and Fong (1993) conrm the

signicance of the prior study of accounting and mathematics as well as personality type,

in predicting academic performance. Similar results by Tho (1994) found the prior study

of high school accounting, mathematics and grades achieved in studies of high school

economics to be signicant in explaining academic performance. The signicance of prior

study of accounting and mathematics as predictor variables of academic performance is

also consistent with the ndings of others including Eskew and Faley (1988), Farley and

Ramsey (1988), and Naser and Peel (1998). Other commentators including Doran et al.

(1991) produce conicting conclusions concerning the impact of prior accounting

knowledge on academic performance in two accounting courses Accounting Principles I

and II (API and APII). They found prior study of high school bookkeeping to be positively

related to performance in API but negatively related to performance in APII.

The impact of gender is also widely studied, but the research ndings are often

contradictory and hence inconclusive in nature. Fraser et al. (1978) and Mutchler et al.

(1987) found that female students outperform their male counterparts. Findings by Tyson

(1989) support this view and conclude that female students outperform male students in all

sections of an introductory accounting class. However, Lipe (1989) failed to nd any

evidence of a gender effect. Similarly, Auyeung and Sands (1994) found no difference

between the performance of male and female students. In contrast, Koh and Koh (1999)

found gender, previous working experience, academic aptitude and age to be signicant

predictors of academic performance. Doran et al. (1991) produced further conicting

94 Gracia and Jenkins

results in their study of the impact of gender on performance in two accounting courses

(API and APII). They found that men outperform women in API, but not in APII.

Other studies have focused on the impact of entry qualications on academic

performance. Studies by Chapman (1994, 1996, 1997) primarily demonstrate the variability

of standards in UK university departments using A level grades as a measure of input

quality. A further study by Paton-Salzberg and Lindsay (1993) found that paid work has

a signicant and negative effect on progress by increasing the rate at which modules are

failed.

The literature review reveals that much of the work on the factors affecting student

performance is quantitative in nature, focusing mainly on rst year students. In addition

much of this quantitative research demonstrates the weak and often conicting relation-

ships that exist between student performance and background characteristics. One

explanation for the conicting ndings of UK studies may be that results are outdated due

to the changing education environment in the last ten years specically the downward

drift of A level standards; the expansion in higher education; widening and increasing

participation rates; increasing cost pressures on institutions; and the replacement of student

grants with loans. Other studies from outside the UK may produce ndings that are

culturally specic and the lessons may not be readily transferable to the UK. Despite their

different ndings, all these studies have one thing in common they are positivistic and

the primary research approach is quantitative. Each attempts to establish a statistically-

valid cause-effect relationship, focusing on the statistically measurable which are largely

background factors.

The disparate results of these studies may suggest that academic performance is not a

simple phenomenon that can be predicted on the basis of a selection of demographic data,

a view supported by Bartlett et al. (1993). It seems likely that there are more active and

subjective forces at work in determining performance that are not captured by statistical

studies. Reliance on quantitative data alone precludes a deeper understanding of the

perception and feelings of students towards their studies and their impact on academic

performance.

Some commentators have focused on this experiential perspective of learning. Boud

(1988) argues that students with a higher level of personal responsibility may become

more actively involved and engaged with the subjects studied and stresses the central

importance of autonomy in student learning. Others, including Barnett (1992) support this

argument. Candy et al. (1994) identify a wider spectrum of learning skills including

personal skills and attributes as important for effective learning.

These issues of personal responsibility and the role of personal skills have long been

linked to effective education. Carl Rogers (1969) founded the person-centred approach to

counselling which places self-awareness, personal responsibility and reection at its core.

He extended his humanistic ideas beyond the counselling arena and into education and

concludes that participative learning, where the learner takes personal responsibility for his

learning, is most effective. Kluever and Green (1998) also emphasize the role of personal

responsibility in learning and created a Responsibility Scale assessment for use with

students. Other researchers in the eld also focus on self-directed learning. Knowles

(1975) concludes that self-directed learning is more in line with an adult s natural process

of psychological development and creates better learners. He maintains that learners who

enter educational programmes using more open and independent learning regimes (such as

higher education) need to be self-directed in their approach and held that if such skills

An exploration of student failure 95

were lacking this causes anxiety, frustration and often failure. Others connect self-directed

learning with personal change. Brookeld (1988) stresses the importance of critical

reection and the creation of personal meaning in the context of effective learning.

The learning process itself also receives a signicant amount of research attention,

especially in relation to cognition. Others including Goleman (1995) and Boler (1999),

have raised the prole of emotion as a component of intelligence. Goleman maintains that

self-awareness, self-responsibility and empathy are important determinants of generic

intelligence, necessary to maximise intellectual potential.

Learning is clearly a complex phenomenon involving changes in knowledge, under-

standing, skills and attitudes brought about by experience and reection upon that

experience. A large part of the research on learning focuses on the issues of cognition, and

within accounting education on demographic data. Whilst the importance of these areas is

acknowledged, increasingly the signicance of other aspects of learning, such as personal

responsibility, personal meaning and an individual s subjective experience are being

recognized. It is these areas that this study considers

Research method

Exploratory research requires open-ended methods of data gathering and analysis and

hence qualitative research methods have been employed. The qualitative approach adopts

a grounded theory perspective. Grounded theory is . . . one of the interpretative methods

that share the common philosophy of phenomenology that is, methods that are used to

describe the world of the person or persons under study , (Hussey and Hussey, 1997,

p. 70). It comprises a series of in-depth semistructured interviews with students from the

second and nal year cohorts enrolled on the BA (Hon) Accounting and Finance at a

University Business School in the academic year 1999/2000. The interviews were taped

and transcribed. This permitted a detailed comparative analysis of the similarities and

differences between students. The analysis focused upon the impact of experiential factors

on individual academic achievement.

Sample selection

A random sample of 42 students was selected to ensure a mix of academic proles. A

simple measure of academic prole was used whereby students who passed all modules in

their previous year, at the rst sitting, were placed in a rst subgroup (50 students), and

those who had failed one or more modules at the rst sitting were placed into a second

subgroup (46 students). Equal numbers of students were then drawn randomly from these

two subgroups.

Such sampling attempts to adequately capture the heterogeneity in the population and

provide a fairer representation of the cohorts under investigation. Within the sample there

was an even balance of students in terms of academic prole, gender and year of study,

increasing condence in the data collected and its subsequent analysis.

Students were approached via a standard letter that explained the purpose of the research

and requested participation in the study. All selected students agreed to be interviewed.

Data collection

This primarily comprised 18 individual, in-depth interviews. Prior to these being

undertaken, four group interviews were conducted with the remaining 24 students from the

96 Gracia and Jenkins

sample. The representative random balance across the individual and group interview

clusters was maintained. The purpose of the preliminary group interviews was to expose a

contextual picture of student experience and permit students themselves to identify

meaningful areas of that experience. These areas were used to directly inform the

individual interview design, increasing the relevance of its content to the participants and

the research aim itself (Bogdan and Biklen, 1992).

Group interviews were used in the preliminary stage to exploit group interactions which

facilitate open discussion and thereby increase accessibility to data (Morgan, 1997).

However, it is recognized that dominant individuals may colour the overall group views,

but any potential undue inuence is mitigated by the individual interview content also

being informed by the literature search. The subsequent individual interviews were used to

explore student failure by providing an in-depth insight into the student experience,

capturing data rich in its experiential content. As such, it is this deep individual data that

is analysed to explore any differences between the experiences of students with differing

academic proles against the broad context. Maxwell (1996) recommends such con-

textualizing of qualitative data, to augment understanding by identifying conceptual

linkages between emergent categories and their surrounding context.

The individual interviews were undertaken by the same interviewer, in the same

interview room recognizing the value of context and setting. They were semistructured

and conducted using nondirective and reective techniques throughout, allowing explora-

tion of the issues via open questioning and encouragement to expand responses. Reective

techniques provide participants with an opportunity to corroborate or clarify responses.

This permits the interviewer to test his/her understanding of participant meaning and

serves as a strong check on the integrity of the data as it is collected. The content of the

individual interviews comprised potentially inuential experiential areas identied from

the existing education literature and the evaluation of the group interviews as

follows:

c Reasons for choice of institution and subject and motivation to study.

c The learning experience.

c The social dimension of learning.

c Control in the learning process.

c Expectation and experience of staff.

c Student rights and responsibilities.

c Experience of, and reection on, assessment and module failure.

c Personal reections.

Sufcient exibility was maintained to enable the order and phrasing of questions to be

varied, if necessary. Each individual interview was 5565 minutes in length and taped

with interviewee permission in its entirety to allow complete data capture and subsequent

transcription. Whilst it is recognized that audiotape only captures the spoken conversation,

omitting the visual aspects of facial expressions and body language, it was felt that video-

recording interviews would intrude on the interview process and hence impinge upon data

collection and compromise its validity.

Data analysis

The semistructured nature of the interviews allowed some structuring of the data prior to

data collection. This preliminary structuring generated a series of categories within which

An exploration of student failure 97

data for each interviewee was transcribed and checked by the researchers. Such self-

transcription with repeated reading of the transcripts allowed fuller immersion in the data,

enhancing understanding and also providing transcription validity and reliability.

Data was analysed using open coding techniques to establish the emergent themes and

sub-themes. Codes were initially established independently by both researchers. The

researchers then compared and rigorously discussed these independently derived codes as

part of an iterative process of data interpretation, continuing until consensus of data coding

and analysis was achieved. This encouraged a more objective and detailed exploration of

the individual data.

Results and discussion of ndings

To protect the condentiality of the participants in this research the Pass students are

denoted P19 and the Fail students F19, in the analysis that follows.

The focus of the investigation is to seek to understand, through student experience, why

some students pass and others fail even though they are subjected to the same teaching and

learning environment. To this end it is the areas of difference between the experience of

pass and fail students that is of interest as possible areas of explanation. The analysis of the

data revealed a number of interesting differences as follows:

When reecting on their own academic failure(s), F students cite a myriad of underlying

reasons and explanations. Common rationales include a poor memory; lack of adequate

revision, attendance, time-management, motivation, encouragement or interest in a subject;

poor teaching and illness.

I didn t do enough work. F2

I let things slide and left it too late. F4

I just didn t attend any classes most of the time. F1

I left things to the last minute and I just ran out of time to revise. F5

I think I failed modules because I didn t like them. F7

F students almost invariably expressed failure as a personal failing regardless of the

reasons underlying their failure, which clearly demonstrates the potential personal impact

that failure has on students. This acceptance of failure at a personal level may indicate that

failure is internalized by students creating their view of failure as some form of personal

deciency. There is some support for this within the data:

I just have a really bad memory. F3

I don t deserve to be on the nal year. F5

I m no good at organizing myself all my course notes are all over my bedroom

oor I don t know where to start. F6

I failed because of my lack of application I m really bad at getting down to

work. F8

I nd it hard to concentrate I always have done. F9

These initial rationales for failure were subsequently explored at a deeper level with

students, which revealed a series of possible explanatory factors as follows:

98 Gracia and Jenkins

1. The impact of affect

A number of F students stated that their initial decisions to enter university and study

accounting were not driven by personal desire, or were unclear as to how these decisions

had arisen:

I came to university, well I wasnt going to come because I couldnt nd a course

that I liked, my mates were saying that I ought to go to university, so I thought OK

Id apply. I wanted to do Law, but I didn t get the points. F1

There wasn t a particular reason . . . I always wanted to be an architect. F2

I felt under pressure to come . . . peer pressure mainly . . . I had no intention of

coming. F3

I didn t want to do accountancy. I wanted to do Art and Design but Im not very

good at drawing. My friend was doing accountancy so I thought I would try it. Id

rather be at a different university; this university is too close to home really.

F4

To some extent F students may be seen as providing negative reasons to support their

choices. In contrast, most P students provide positive reasons to support their choices of

where and what to study. These P students frequently relate their initial decision to study

at university to some form of encouragement, from family and friends and linked their

choice of accounting to an afnity or comfortable association with numeracy, or a prior

study of accounting.

I felt that this university was more exible to the needs of mature students.

P1

I had friends studying here and they recommended it. The course has a sandwich

year and you can get a years work experience which means youve got more

chance of getting a job at the end of it. P2

My Dad has a business and from a young age Ive sat with my Mum when she

was doing the accounts. As I got older she gave me accounting jobs to do. I ve

always wanted to do accountancy. P3

I ve had an interest in gures all along and my parents were very encouraging

when I wanted to come. P7

I chose accountancy because I had studied it on my Access to Education course

and decided that I really liked it. P4

This raises the possibility that the vague or negatively focused patterns of reasoning of F

students may colour the longer-term attitude of students towards their studies, in a way that

somehow adversely affects academic performance. One possible mechanism through

which this inuence might be exerted is affect i.e. mood and general outlook. There is

increasing evidence that shows that affective states have a powerful inuence on an

individual s thought and behaviour patterns. Affect has a profound inuence on the

memories we retrieve and the information we notice and learn (Ciarrochi et al. 2001,

p. 47). Furthermore, Ciarrochi et al. hold that affect inuences both the process of thinking

and the content of thinking, judgements and behaviour. They also state that affect infusion

increases when individuals engage in thinking that uses memory-based information, which

is typical of the pattern of learning that predominates in higher education. This view of the

impact of affect on learning is supported by Adolphs and Damasio (2001) who state that

affect inuences all other aspects of cognitive functioning, including memory, attention

An exploration of student failure 99

and decision making (p. 45). The ndings of Suls (2001) also indicate that feelings of

negative affect can create negative thinking and attitudes that impair an individual s ability

to manage the situations he/she faces.

Given this established impact of affect on learning (amongst other things) this may

provide a possible explanation as to why students with negatively-focused patterns of

reasoning may not perform as well academically as their counterparts. Indeed, responses

from F students seem to support the role of affect in interfering with their academic

performance:

Sometimes I nd it difcult to motivate myself. I know I should be doing some

work, but I just can t make myself do it if I don t feel like it. F8

Its always been the case that if I m not in the mood to revise that s it! There s

no point in even trying because I know that I won t take any of it in anyway. So

much of it is just memory work anyway and thats not my strong point. F6

I m here for the social-life really I d really rather go out with the boys than stay

in and study! F9

2. Patterns of participation

F students are frequently critical of their own levels of condence and feel that this

adversely impinges on their ability to enter into verbal participation in classroom

discussions.

I m really quiet in the classroom and I don t like it if the teacher asks me a

question. I can feel people looking at me and I ll say that I don t know, even if I

do, just to stop the process. F8

I m naturally shy I d like to be able to talk more but it just makes me feel really

stressed and uncomfortable. F6

It depends on how many people you know in the class. If you don t know people

there s not that same sense of security about participating. F4

I m usually very quiet and I don t say very much. I m just not condent enough

and I get very embarrassed if I don t give the right answer. F3

I usually keep quiet in case I get things wrong. F1

I am afraid to express my opinion I don t want the others to laugh at me.

F2

Generally speaking the level of difculty is less amongst the P students:

I don t mind participating in the tutorials. If I ve got something to say I ll just say

it. P2

I just say what I want. I m not bothered if it s wrong or not. P1

I am sometimes a little bit afraid to discuss my opinions. It s important that the

tutor is not too critical and is supportive of the student s ideas. P4

Many of the F students appear fearful that their answers will be incorrect, stemming from

anxious sensitivity towards the reaction of others and a lack of condence in their own

abilities. Such feelings inhibit participation, which may interfere with a student s ability to

fully engage with the learning situation and the other participants in the learning

experience:

100 Gracia and Jenkins

I won t go to a class if I don t know anyone to talk to. F5

I m not very good at mixing with the other students or asking for help if I get

stuck. I often feel that I am alone on this course. F1

I think that the other students don t listen to me they look bored with me or act

as if they cant follow what Im saying. F7

Sometimes because of the lecturer I did not feel like going to the class . . . some

lecturers denitely put up barriers to keep you out I just feel it! F3

Such impairments may damage students ability to maximize their learning potential by

restricting their level of active engagement.

Active engagement with the course can take a variety of forms including verbal

participation. Another broad measure of active engagement with the course is that of

attendance at classes. Attendance records for the academic year 1999/2000 show that the

recorded attendance rate of P students (P1P9) ranges from 98%67%, with an average

attendance of 88%, whilst that of the F students (F1F9) over the same period ranges from

92%53%, with an average attendance rate of 69%. The lower rates for the F students may

indicate that their levels of active engagement with the course are less than that of their P

contemporaries.

Another area of engagement for the student is that of establishing a relationship with the

tutor. Most students highlight the importance of the tutor as central contributors to their

best and worst learning experiences. Most felt that the difference between the two

extremes is tutor-related. Learning experiences cited include:

One tutor allowed us to sit down in small groups and discuss our opinions. I

started to grow in condence and I really enjoyed that. F3

One lecturer had a really droning voice and just used to give us a handout and

then just read from it all the time. Some students actually fell asleep in her class!

F4

It was the lecturer s fault. He wasn t at all interesting and he used to teach us

with his eyes closed. It seemed that he expected us to do all the work and provide

all the interest. F2

This underlines the pivotal role that tutors have in striking a balance between providing too

much support (which may collude with students to strip them of control, encourage

passivity and stie development of autonomous study patterns) and too little support

(which can isolate students, deterring engagement and frustrate their efforts to become

responsible, autonomous learners). The onus is therefore on tutors to provide appropriate

levels of support and encouragement. The provision of such appropriate levels of support

and encouragement may be even more necessary for F students who may already be

struggling with poor course engagement; lower levels of attendance; a greater tendency to

feel anxious about participating verbally in the classroom; and a preference for abdicating

control for their learning into the hands of a willing tutor.

3. Expectation gap

There is recognition by some students all P of the distinction between teaching and

learning and the active role that students have to play in the learning process:

It s the student s responsibility to work outside of the lectures. P2

It s important to work with the staff, who are there to guide you. P3

An exploration of student failure 101

Teaching and learning aren t the same thing the tutor starts you off, but you

have to go and do the work yourself. P9

P students tend to view their relationships with tutors as reciprocal a partnership

approach within which they work with tutors and recognize that they have to do the

work . This presents a realistic view of the teaching process as something they interact

with to maximize knowledge-transfer and achieve learning outcomes. In contrast, F

students tend to view their relationship with tutors in more dependent and reliant terms

with a narrower view of the teaching process as the means by which they passively receive

knowledge-transfer:

They should be doing all they can to help me to get an A . Their role doesnt end

when the class nishes; they should be prepared to help outside the class. F3

To educate me and to explain the things that we don t understand! F4

They should pass over their knowledge explaining it to us. F1

I need the tutor to direct my learning. F2

Tutors should teach us everything that we need to know otherwise they are not

doing their job properly! F7

I have to push the tutors sometimes to get them to tell me everything I need to

know it makes me feel like a stalker! F8

These F responses largely view the tutor as a holder or store of knowledge and the teaching

process as knowledge-transfer and indicates a much heavier reliance on the tutor. From

this position it is arguable that P students hold more realistic expectations of the role of

tutors whilst an expectation gap is exposed between F students and their tutors.

When exploring with F students the existence of such an expectation gap and its

impact on academic performance, a number of issues arise. Firstly students cite prior study

experience as a possible contributor to the creation of the expectation gap . Many students

come to university directly from school where more directive approaches to learning have

been employed. Some responses seem to indicate that students had assumed that studying

in HE would be similar to that at school:

Coming to university straight from school was quite a shock! In school you talk

through everything, and the teachers will do everything they can to make sure that

you pass. F6

I am used to being in school where everything is done for you the teachers gave

you all the notes and you didn t have to read many books! It is very different in

university and I found it difcult to adjust. F3

Secondly, the issue of the reduced number of contact hours, in comparison to students

prior study experience. This requires students to be able to manage their own learning

outside of formal contact hours and some students felt that they needed more help to

manage this effectively:

In university you see the tutors a lot less than you did at school, and you have to

do a lot of stuff on your own I nd that really hard. F9

It s harder than I thought it was going to be. I nd it hard to structure my own

studying. F2

What F students appear to be describing is that their tutor-expectations are based on their

prior learning exposure and experience and not on realistic information about the learning

102 Gracia and Jenkins

approaches employed within HE. However, if these expectations are not met, students are

faced with the challenge of adapting their approach to learning. If students do not

effectively manage this transition into HE it may compromise their learning. As one

particular F student stated:

It s not just about the technical stuff I also need the tutors to help me to learn

how to study. F7

4. The locus of control over learning

When considering failure the issue of control over learning was raised. Paradoxically,

whilst F students were ready to accept the responsibility for their failures they were

reluctant to take control of their learning. All the F students express dissatisfaction with the

level of control they have feeling it is too much and reject the idea of taking more

control for their learning:

I need the tutor to organize my learning . . . I m no good at organizing myself

I need more self-discipline. F4

It s easier if everything is decided up front by the tutor I prefer them to be in

control it gives me less to worry about. F2

I don t think its practical to have too much control. F3

I don t really want to take control of the learning I m not even sure how I could

get control of it. If I had control and then I failed I would feel that it was my

fault! F6

In contrast, P students generally demonstrate some level of control over their learning:

I am the one who is here to study, so I should do that . . . it is not the tutor s

responsibility. P2

In the classroom I feel 100% in control. P1

I have lots of control I can do as much work as I want outside of the class. Its

up to me to read into it as much as I like. P4

As such F students appear to be more control-averse than their P counterparts and reveal

a preference for the tutor controlling their learning. This could be interpreted as the

adoption of a more passive approach to their learning. This desire to be controlled or

directed suggests that F students within the sample place the locus of control for their

learning with others, whilst P students seem more likely to place the locus of control with

themselves and adopt a more active approach to their learning. Again the adoption of

control-averse or control-accepting patterns of behaviour by a particular student may be

linked to their prior educational experiences as discussed above, which may have provided

a more directed approach that some students struggle to move away from and towards a

more autonomous style of learning.

Shared characteristics of F students and support mechanisms

The research reveals a number of broad and common experiential features or character-

istics amongst the F students. If students exhibit these characteristics it is possible that it

may render them more susceptible to failure and hence be useful in understanding the

differing levels of academic performance between students.

These features comprise:

An exploration of student failure 103

c Negative focus of reasoning and the impact of affect

The vague or negatively-focused reasoning underlying the initial study choices of F

students may belie a longer term affective state which inuences the longer-term attitude

of students towards their studies, in a way that adversely affects academic performance.

Provision of sustained student support strategies that include opportunities for long-term,

open discussions of affective and attitudinal factors may be useful here.

c Patterns of participation

F students describe more reticence to participate than P students. Feelings of lack of

condence and anxiety about the reaction of peers and tutors if they give an incorrect

response act as participation inhibitors. These negative feelings concerning self may also

impair a student s engagement with the course in terms of developing supportive study

relationships with fellow students and their tutors and may interfere with patterns of class

attendance and subsequent academic performance. The provision of a non-judgemental

classroom climate that offers open acceptance of students may be useful in fostering

student discussion and development and in actively supporting engagement. In addition it

may be sensible to monitor attendance as an early-warning indicator of engagement

difculties.

c Tutor expectations gap

P and F students view the relationship between themselves and their tutors in different

ways. F students are inclined to expect the tutor to actively provide learning as an

educational product, viewing themselves as the passive recipients of the learning product.

Such an orientation may stem from familiarity and exposure to more directive forms of

learning and the development of a reliance on such methods. This may make transition into

HE troublesome for the student as a result if the shift to more autonomous learning

approaches is not effectively managed. P students, in contrast, are more inclined to view

themselves as active participants in the learning process. Support mechanisms and

information exchange that focus on establishing realistic expectations of the roles and

responsibilities of tutors and students, together with supported transition into HE may

serve to facilitate the development of a partnership approach to learning and hence bridge

the expectations gap.

c Taking control of learning

P students present as more control-accepting than their F counterparts who tend to be more

control-averse. This links with the emerging view of F students as being more passive in

their approach to learning. Such passivity is an inevitable by-product of the abdication of

control and a preference for being directed in their learning. This could perhaps be

interpreted as a form of educational immaturity, where students who may have developed

tutor-reliant forms of learning are unable to adapt their learning strategies to overcome

their passivity. Again, support mechanisms and information exchange may be useful in

encouraging development of active self-responsibility in the learning process.

Despite its cause, failure appears to be internalized by F students who express it largely

in terms of personal deciencies. This strongly demonstrates the personal and emotional

cost of failure to students especially given students dominant assessment-focus. There

may be a case here for re-educating students and ourselves as tutors in terms of how we

perceive failure . Internalizing it as a form of personal deciency is at one end of a

spectrum of responses. An alternative view is that it is a valuable learning experience in

itself that provides a tangible opportunity to understand where improvement and

104 Gracia and Jenkins

development can be made! It is somewhat ironic that failure itself can be a strong building

block of learning and, as such, our attitude towards it may warrant change.

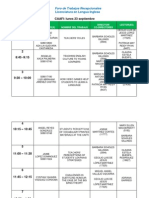

Failure is an important and personal event in the life of a student. Table 1 maps the

particular features identied above to individual students. Such mapping demonstrates how

the experience of each student relates to particular factors. This is important in that it

rstly recognises the individual nature of each student and the reasons underlying their

consequent failure whilst at the same time establishing areas of common experience and

potential rationales for failure across the student sample.

Conclusions and further research

The identication of such common features is useful in terms of understanding the factors

that may render students susceptible to failure and hence permit the early identication of

vulnerable students and the development and targeting of appropriate support mechanisms

to mitigate any potential impairment to academic performance.

Using the areas of difference derived from the study the authors propose to attempt to

develop a predictive model of academic performance with the potential of acting as an

early warning indicator of those students who exhibit the behaviour patterns and attitudes

that may render them susceptible to failure at the start of their studies.

Such a predictive tool does have potential ethical issues connected with it in terms of

providing an appropriate response aimed at support and remedy, subsequent to difculties

being identied. It is the intention to develop such support strategies in tandem with the

predictive model to obviate such ethical issues.

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to the university students who took part in the research and to the

many constructive comments of the anonymous reviewer.

References

Adolphs, R., and Damasio, A. (2001) The interaction of affect and cognition: a neuro-biological

perspective. In J.P. Forgas (ed.) Handbook of Affect and Social Cognition. Mahwah, NJ:

Erlbaum, pp. 3947.

Table 1. Mapping potential explanatory factors of failure

Possible failure factor

Student references in body of

report (F1F9)

Negative focus of reasoning and the impact of affect F1, F2, F3, F4, F6, F8, F9

Reluctant patterns of participation and its impact on

engagement

F1, F2, F3 F4, F5, F6, F7, F8

Tutor expectation-gap and the impact on transition F1, F2, F3, F4, F6, F7, F8, F9

Internalizing failure personal importance F3, F5, F6, F8, F9

External locus of control over learning and the

development of control-averse behaviour

F2, F3, F4, F6

An exploration of student failure 105

Auyeung, P.K. and Sands, D.F. (1994) Predicting success in rst year university accounting using

gender-based learning analysis. Accounting Education: an international journal 3(3),

25972.

Baldwin, B.A. and Howe, K.R. (1982) Secondary-level study of accounting and subsequent

performance in the rst college course, The Accounting Review 57(3), 61926.

Barnett, R. (1992) Improving University Education. Milton Keynes: SRHE and Open University

Press.

Bartlett, S., Peel, M.J., Pendlebury, M. and Groves, R. (1992) An Analysis of Student Performance

in Undergraduate Accounting Courses. ACCA Occasional Paper 13. London: Association of

Chartered Certied Accountants.

Bartlett, S., Peel, M.J. and Pendlebury, M. (1993) From fresher to nalist: a three year analysis of

student performance on an accounting degree programme. Accounting Education: an

international journal 2(2), 11122.

Bergin, J.L. (1983) The effect of previous accounting study on student performance in rst college-

level nancial accounting course. Issues in Accounting Education Vol. 1, 1928.

Bogdan, R.G. and Biklen, S.K. (1992) Qualitative Research for Education, 2nd edn. Boston, MA:

Allyn & Bacon.

Boler, M. (1999) Feeling Power Emotions and Education. London: Routledge.

Boud, D. (1988) Developing Student Autonomy in Learning, 2nd edn. London: Kogan Page.

Brookeld, S. (1988) Understanding and Facilitating Adult Learning. San Francisco: Jossey

Bass.

Candy, P., Crebert, G. and O Leary, J. (1994) Developing Lifelong Learners through Undergraduate

Education. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service.

Chapman, K. (1994) Variability of degree results in geography in UK universities. Studies in Higher

Education 19(1), 89103.

Chapman, K. (1996) Inter-Institutional Variability of Degree Results. London: HEQE.

Chapman, K. (1997) Degrees of difference: variability of degree results in UK Universities, Higher

Education 33 13753.

Ciarrochi, J., Forgas, J.P. and Mayer, J.D. (2001) Emotional Intelligence in Everyday Life A

Scientic Inquiry. Philadelphia: Psychology Press.

Doran, B.M., Benillon, M.L. and Smith, C.G. (1991) Determinants of student performance in

accounting principles I and II. Issues In Accounting Education 6(1), Spring, 7384.

Eskew, N. and Faley, R.H. (1988) Some determinants of student performance in the rst college-

level nancial accounting course. The Accounting Review 63(1), 13747.

Farley, A. and Ramsey, A. L. (1988) Student performance in rst year tertiary accounting courses

and its relationship to secondary accounting education. Accounting and Finance 28(1)

2944.

Fraser, A.A., Lyttle, R. and Stolle, C. (1978) Prole of female accounting majors: academic

performance and behavioral characteristics. The Woman CPA, October, 1821.

Goleman, D. (1995) Emotional Intelligence: Why it Can Matter More Than IQ. New York:

Bantam.

Gul, F.A. and Fong, S.C.C. (1993) Predicting success for introductory accounting students: some

further Hong Kong evidence. Accounting Education: an international journal 2(1), 3342.

Hussey, J. and Hussey, R. (1997) Business Research: a Practical Guide for Undergraduate and

Postgraduate Students. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Kluever, R. and Green, K. (1998) The responsibility scale: a research note on dissertation

completion. Educational and Psychological Measurement 58(3), 52031.

Knowles, M. (1975) Self-Directed Learning: A Guide for Learners and Teachers. New York:

Association Press.

Koh, M.Y. and Koh, H.C. (1999) The determinants of performance in an accounting programme.

Accounting Education: an international journal 8(1), 1329.

106 Gracia and Jenkins

Lipe, M.G. (1989) Further evidence on the performance of female versus male accounting students.

Issues in Accounting Education 4(1) Spring, 14452.

Maxwell, J.A. (1996) Qualitative Research Design. California: Thousand Oaks, Sage.

Mitchell, F. (1985) School accounting qualications and student performance in the First Level

university accounting examination. Accounting and Business Research 15(58), Spring,

8186.

Mitchell, F. (1988) High school accounting and student performance in the rst level university

accounting course: a UK study. Journal of Accounting Education 6(2), 27991.

Morgan, D.L. (1997) Focus Groups as Qualitative Research. California: Thousand Oaks, Sage.

Mutchler, J.F., Turner, J.H. and Williams, D.D. (1987) The performance of female versus male

accounting students. Issues in Accounting Education 1(1) March, 6368.

Naser, K. and Peel, M.J. (1998) An exploratory study of the impact of intervening variables on

student performance in a Principles of Accounting Course. Accounting Education: an

international journal, 7(3), 20923.

Paton-Salzberg, R. and Lindsay, R.O. (1993) The Effect of Paid Employment on the Academic

Performance of Full-Time Students in Higher Education. Oxford: Brookes University.

Rogers, C.R. (1969) Freedom to Learn. Columbus, Ohio: Merrill.

Schroeder, N.W. (1986) Previous accounting education and college-level accounting examination

performance. Issues in Accounting Education 1(1), 3747.

Suls, J. (2001) Affect, stress and personality. In J.P. Forgas (ed.) Handbook of Affect and Social

Cognition. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, pp. 12749.

Tho, L.M. (1994) Some evidence on the determinants of student performance in the University of

Malaya Introductory Accounting Course. Accounting Education: an international journal 3(4),

33140.

Tyson, T. (1989) Grade performance in introductory accounting courses. Why female students

outperform males. Issues in Accounting Education Spring 4(1), 15360.

An exploration of student failure 107

Вам также может понравиться

- DLL Ict 7 Week 1Документ16 страницDLL Ict 7 Week 1Dan Philip De GuzmanОценок пока нет

- A Practical Approach To Critical ThinkingДокумент25 страницA Practical Approach To Critical ThinkingUfku ErelОценок пока нет

- Students Engagement and Academic Performance AmongДокумент33 страницыStudents Engagement and Academic Performance AmongJoan CanilloОценок пока нет

- Study Habits and Attitudes LocalДокумент19 страницStudy Habits and Attitudes LocalDaverianne Quibael Beltrano75% (8)

- Job Order Cost CH 05 KinneyДокумент34 страницыJob Order Cost CH 05 KinneyLadyromancerWattpad100% (2)

- Neuroscience of Psychotherapy Louis CozolinoДокумент24 страницыNeuroscience of Psychotherapy Louis CozolinoAlyson Cruz100% (2)

- Name: - Date: - Date of Rotation: - Score: - Pediatrics Shifting ExamДокумент5 страницName: - Date: - Date of Rotation: - Score: - Pediatrics Shifting ExamKristine Seredrica100% (1)

- Characteristic of Human LanguageДокумент1 страницаCharacteristic of Human LanguageSatya Permadi50% (2)

- 2013 Study Habits and Attitudes The Road To Academic SuccessДокумент47 страниц2013 Study Habits and Attitudes The Road To Academic SuccessTed Magalona100% (2)

- (Xxakanexx) Hands All OverДокумент147 страниц(Xxakanexx) Hands All OverAna Grace Reconalla Morete100% (8)

- Factors Affecting Grade 10 Learners' Performance in MAPEH RationaleДокумент12 страницFactors Affecting Grade 10 Learners' Performance in MAPEH Rationalejc muhiОценок пока нет

- An Analysis of The Factors That Influence Student Performance: A Fresh Approach To An Old DebateДокумент21 страницаAn Analysis of The Factors That Influence Student Performance: A Fresh Approach To An Old DebateNooraFukuzawa NorОценок пока нет

- Research Report Sad Life (Edited)Документ7 страницResearch Report Sad Life (Edited)Aquila Kate ReyesОценок пока нет

- AbstractДокумент9 страницAbstractsamuel kolawoleОценок пока нет

- Research PaperДокумент9 страницResearch PaperAli MajidОценок пока нет

- Chapter 2 (Final)Документ10 страницChapter 2 (Final)aynОценок пока нет

- Introduction and BackgroundДокумент4 страницыIntroduction and Backgroundinayeon797Оценок пока нет

- 1 s2.0 S1877042811026772 Main PDFДокумент7 страниц1 s2.0 S1877042811026772 Main PDFAldrin ZlmdОценок пока нет

- Review of Related Literature in Academic Adjustment of First YearДокумент3 страницыReview of Related Literature in Academic Adjustment of First YearChanz Caballero Pagayon75% (4)

- Factors Associated With Student Performance in Financial Accounting CourseДокумент16 страницFactors Associated With Student Performance in Financial Accounting CourseCynthia AryaОценок пока нет

- How Much Do Study Habits, Skills, and Attitudes Affect Student Performance in Introductory College Accounting Courses?Документ15 страницHow Much Do Study Habits, Skills, and Attitudes Affect Student Performance in Introductory College Accounting Courses?anon_973357459Оценок пока нет

- TheEffectOfBlendedCoursesOnStudent PreviewДокумент22 страницыTheEffectOfBlendedCoursesOnStudent PreviewDwi AnggareksaОценок пока нет

- Ref4. Accounting For First YearДокумент23 страницыRef4. Accounting For First YearRico Jay EmejasОценок пока нет

- Figlio 2004Документ20 страницFiglio 2004Vanessa AydinanОценок пока нет

- Relationships Between Student Satisfaction and Assessment Grades in A First-Year Engineering UnitДокумент10 страницRelationships Between Student Satisfaction and Assessment Grades in A First-Year Engineering UnitPaddy Nji KilyОценок пока нет

- Relationship Between Pre-Service Teachers' Mathematics Self-Efficacy and Their Mathematics AchievementДокумент14 страницRelationship Between Pre-Service Teachers' Mathematics Self-Efficacy and Their Mathematics AchievementMuh YusufОценок пока нет

- Do Extracurricular Activities Matter? Chapter 1: IntroductionДокумент18 страницDo Extracurricular Activities Matter? Chapter 1: IntroductionJason Wong100% (1)

- Does Class Attendance Affect Academic Performance? Evidence From "D'Annunzio" UniversityДокумент22 страницыDoes Class Attendance Affect Academic Performance? Evidence From "D'Annunzio" UniversityJoanjoy bagbaguenОценок пока нет

- Academic Performance of College StudentsДокумент10 страницAcademic Performance of College StudentsBasir Ahmad KaminОценок пока нет

- Paper 1 BaijouДокумент10 страницPaper 1 BaijouAsmae BerradaОценок пока нет

- Linear Regression Approach To Academic PerformanceДокумент27 страницLinear Regression Approach To Academic PerformanceDessyОценок пока нет

- "Backwash Effects" of Testing On Learning MathematicsДокумент24 страницы"Backwash Effects" of Testing On Learning MathematicsAmadeus Fernando M. PagenteОценок пока нет

- Final - Grit and Teacher Effectiveness of General Elementary Education Teachers Who CWSNДокумент71 страницаFinal - Grit and Teacher Effectiveness of General Elementary Education Teachers Who CWSNmarifeОценок пока нет

- Homework Has Positive Effect On Student Achievement Duke StudyДокумент8 страницHomework Has Positive Effect On Student Achievement Duke Studyerdqfsze100% (1)

- The Relationships Between Students' Underachievement in Mathematics Courses and Influencing FactorsДокумент8 страницThe Relationships Between Students' Underachievement in Mathematics Courses and Influencing FactorsMary KatogianniОценок пока нет

- 2022 9 4 10 QureshiДокумент14 страниц2022 9 4 10 QureshiSome445GuyОценок пока нет

- The Enigma of Academics Revealing The Positive Effects of School Attendance Policies. FINAL. 2 2Документ6 страницThe Enigma of Academics Revealing The Positive Effects of School Attendance Policies. FINAL. 2 2Angelica CarreonОценок пока нет

- Teachers' Beliefs About Assessment and AccountabilityДокумент23 страницыTeachers' Beliefs About Assessment and AccountabilityHERNITA JUSEPA SITOMPUL, S.PD.Оценок пока нет

- The Enigma of Academics Revealing The Positive Effects of School Attendance Policies. FINAL. 2Документ8 страницThe Enigma of Academics Revealing The Positive Effects of School Attendance Policies. FINAL. 2Angelica CarreonОценок пока нет

- 20261-Article Text-52430-1-10-20161221Документ18 страниц20261-Article Text-52430-1-10-20161221Molindu AchinthaОценок пока нет

- The Effects of Family Background and SCH PDFДокумент49 страницThe Effects of Family Background and SCH PDFjefferson Acedera ChavezОценок пока нет

- Factors Affecting Students' Academic Performance in Mathematical Sciences Department in Tertiary Institutions in NigeriaДокумент9 страницFactors Affecting Students' Academic Performance in Mathematical Sciences Department in Tertiary Institutions in NigeriaEducationdavid100% (1)

- Shahzadi and AhmedДокумент14 страницShahzadi and Ahmedزيدون صالحОценок пока нет

- RRL Nov 14Документ4 страницыRRL Nov 14Nancy AtentarОценок пока нет

- RRL University of The West IndiesДокумент17 страницRRL University of The West IndiesDanDavidLapizОценок пока нет

- Icbelsh 1009Документ4 страницыIcbelsh 1009International Jpurnal Of Technical Research And ApplicationsОценок пока нет

- The Effect of Grading Practices On Gender Differences in Academic PerformanceДокумент21 страницаThe Effect of Grading Practices On Gender Differences in Academic PerformanceBek BokОценок пока нет

- The Failure of Educational Accountability To Work As Intended in The United StatesДокумент27 страницThe Failure of Educational Accountability To Work As Intended in The United StatesRobinson Stevens Salazar RuaОценок пока нет

- Educational Interface PostprintДокумент18 страницEducational Interface PostprintLetsie SebelemetjaОценок пока нет

- Theoretical FrameworkДокумент5 страницTheoretical FrameworkKatsuki SenpaiОценок пока нет

- (Alfordy & Othman, 2021) Students' Perceptions of Factors Contributing To Performance in Accounting Principle CoursesДокумент15 страниц(Alfordy & Othman, 2021) Students' Perceptions of Factors Contributing To Performance in Accounting Principle CoursesDark ShadowОценок пока нет

- (Research Article) THE IMPACT OF EMPLOYMENT DURING SCHOOL ON COLLEGE STUDENTДокумент40 страниц(Research Article) THE IMPACT OF EMPLOYMENT DURING SCHOOL ON COLLEGE STUDENTRobertОценок пока нет

- Research PaperДокумент3 страницыResearch PaperKimberly MarajasОценок пока нет

- Do Students' Perceptions Matter? A Study of The Effect of Students' Perceptions On Academic PerformanceДокумент24 страницыDo Students' Perceptions Matter? A Study of The Effect of Students' Perceptions On Academic PerformanceIris DescentОценок пока нет

- Discussion Paper Series: UQ School of EconomicsДокумент33 страницыDiscussion Paper Series: UQ School of EconomicsMara FurushimaОценок пока нет

- Chapter 2Документ23 страницыChapter 2Ronelle San buenaventuraОценок пока нет

- Review of Related Literature and StudiesДокумент13 страницReview of Related Literature and Studiesangelo arboledaОценок пока нет

- Teachers' Instructional Practices and Its Effects On Students' Academic PerformanceДокумент6 страницTeachers' Instructional Practices and Its Effects On Students' Academic PerformanceCALMAREZ JOMELОценок пока нет

- EJ1366649Документ8 страницEJ1366649Kressia Pearl LuayonОценок пока нет

- Student Perceptions of Pedagogy and Persistence in CalculusДокумент20 страницStudent Perceptions of Pedagogy and Persistence in CalculusReychille AbianОценок пока нет

- REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE - Revised - EditedДокумент9 страницREVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE - Revised - EditedEric Mark ArrezaОценок пока нет

- Marann ByrneДокумент11 страницMarann ByrneNguyễn Trần Bá ToànОценок пока нет

- The Establishing of Senior High Curriculum Has MadДокумент3 страницыThe Establishing of Senior High Curriculum Has MadLady Aleah Naharah P. AlugОценок пока нет

- The Impact on Algebra vs. Geometry of a Learner's Ability to Develop Reasoning SkillsОт EverandThe Impact on Algebra vs. Geometry of a Learner's Ability to Develop Reasoning SkillsОценок пока нет

- Testing Student Learning, Evaluating Teaching EffectivenessОт EverandTesting Student Learning, Evaluating Teaching EffectivenessОценок пока нет

- Effects of an Inclusion Professional Development Model on Inclusion Knowledge and Perceptions of Regular Middle School EducatorsОт EverandEffects of an Inclusion Professional Development Model on Inclusion Knowledge and Perceptions of Regular Middle School EducatorsОценок пока нет

- Legazpi CityДокумент7 страницLegazpi CityLadyromancerWattpadОценок пока нет

- Chapter12 - AnswerДокумент26 страницChapter12 - AnswerAubreyОценок пока нет

- Noynoy Aquino SONA 2013Документ129 страницNoynoy Aquino SONA 2013LadyromancerWattpadОценок пока нет

- Musical IntelligenceДокумент18 страницMusical IntelligenceLadyromancerWattpadОценок пока нет

- Job Order Cost CH 05Документ35 страницJob Order Cost CH 05LadyromancerWattpadОценок пока нет

- Job Order Costing: QuestionsДокумент3 страницыJob Order Costing: QuestionsLadyromancerWattpadОценок пока нет

- Job Order Cost System: Richmond-Lady-Boat-Show-Price PDFДокумент33 страницыJob Order Cost System: Richmond-Lady-Boat-Show-Price PDFLadyromancerWattpadОценок пока нет

- The Circulatory SystemДокумент2 страницыThe Circulatory SystemLadyromancerWattpadОценок пока нет

- Non-Nursing Theories A. Systems TheoryДокумент11 страницNon-Nursing Theories A. Systems Theoryethics wixОценок пока нет

- Semi-Detailed Lesson Plan in Grade 1: I ObjectivesДокумент5 страницSemi-Detailed Lesson Plan in Grade 1: I ObjectivesMarjorie Sag-odОценок пока нет

- Igwilo Edel-Quinn Chizoba: Career ObjectivesДокумент3 страницыIgwilo Edel-Quinn Chizoba: Career ObjectivesIfeanyi Celestine Ekenobi IfecotravelagencyОценок пока нет

- Theme and Main Idea Lesson 2Документ4 страницыTheme and Main Idea Lesson 2api-581790895Оценок пока нет

- The Effect of Mindset On Decision-MakingДокумент27 страницThe Effect of Mindset On Decision-MakingJessica PhamОценок пока нет

- Grade 4 SYLLABUS Check Point 1Документ2 страницыGrade 4 SYLLABUS Check Point 1Muhammad HassaanОценок пока нет

- Brihad-Dhatu Rupavali - TR Krishna Ma Char YaДокумент643 страницыBrihad-Dhatu Rupavali - TR Krishna Ma Char YaSatya Sarada KandulaОценок пока нет

- Krista Pankau Cover LetterДокумент3 страницыKrista Pankau Cover Letterapi-514564329Оценок пока нет

- Hiring Recent University Graduates Into Internal Audit Positions: Insights From Practicing Internal AuditorsДокумент14 страницHiring Recent University Graduates Into Internal Audit Positions: Insights From Practicing Internal AuditorsBrigitta Dyah KarismaОценок пока нет

- Planificare Lectii Limba Engleza GrădinițăДокумент4 страницыPlanificare Lectii Limba Engleza Grădinițăbaba ioanaОценок пока нет

- Psychotherapy Prelims ReviewerДокумент14 страницPsychotherapy Prelims ReviewerAnonymous v930HVОценок пока нет

- Columbia University Map LocationsДокумент2 страницыColumbia University Map LocationsElizabeth BОценок пока нет

- Essay About ResponsibilityДокумент6 страницEssay About Responsibilityngisjqaeg100% (2)

- Week 7 Lesson Plans 2Документ4 страницыWeek 7 Lesson Plans 2api-334646577Оценок пока нет

- Nutech University Admission SlipДокумент3 страницыNutech University Admission SlipaliiiiОценок пока нет

- JD BD (India) BooksyДокумент1 страницаJD BD (India) BooksyytrОценок пока нет

- Ncert Exemplar Math Class 11 Chapter 11 Conic-SectionДокумент33 страницыNcert Exemplar Math Class 11 Chapter 11 Conic-SectionDhairy KalariyaОценок пока нет

- HR Executive Interview Questions and AnswersДокумент2 страницыHR Executive Interview Questions and AnswersRaj SinghОценок пока нет

- Foro de ER - Sept - FinalThisOneДокумент5 страницForo de ER - Sept - FinalThisOneAbraham CastroОценок пока нет

- Demo K-12 Math Using 4a's Diameter of CircleДокумент4 страницыDemo K-12 Math Using 4a's Diameter of CircleMichelle Alejo CortezОценок пока нет

- Professional Development Plan (Required)Документ4 страницыProfessional Development Plan (Required)api-314843306Оценок пока нет

- VONG 1 - 2020-2021 - Key - CTДокумент2 страницыVONG 1 - 2020-2021 - Key - CTKhánh LinhОценок пока нет

- Emotional Intelligence CompetencyДокумент4 страницыEmotional Intelligence CompetencySiti ShamzelaОценок пока нет

- Perdev 2qДокумент1 страницаPerdev 2qGrace Mary Tedlos BoocОценок пока нет

- The Bridging ProcessДокумент12 страницThe Bridging ProcessAce Kenette VillanuevaОценок пока нет