Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Diverse Experiences Diverse Needs

Загружено:

Brett_Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Diverse Experiences Diverse Needs

Загружено:

Brett_Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

FINAL REPORT

Diverse Experiences

Diverse Needs

Accommodation at the

University of Toronto

Faculty of Law

June 2014

image: CC Rose Craft

Introduction

Accommodation for illness and bereavement at the University of Toronto Faculty

of Law occurs at the discretion of the Offce of the Assistant Dean of Students

(OADS). Because of the sensitive and deeply private nature of many accommodation

requests, experiences with the accommodation system are generally kept private.

This combination of an ad hoc, discretionary regime and the deeply private nature

of requests has created diffculties with assessing how well the current system is

working for students who have accessed it. Most students know people who have had

negative experiences with the regime, but there is no clear picture about how well it

is operating.

This project seeks to fll these gaps in our knowledge about how students feel about

the current system. It will identify strengths and challenges in the practices of the

law school with respect to accommodation. It will present recommendations made by

people who have participated in the regime about how to improve the system.

This report should be seen as a starting point of a larger conversation about how to

build on the accommodation regimes strengths, and address its weaknesses. The

results of this study are qualitative, not quantitative, and therefore they are not

statistically signifcant. However, this report provides insights into the way students

have experienced the system. It is also worth noting that there was remarkable

consistency in the feedback we received about the regime across these 20 interviews.

Krista Nerland & Marcus McCann

Class of 2014, University of Toronto Faculty of Law

2

Research was to be conducted by two upper year law students.

The project terms of reference were designed with the

advice of a group of students who have interacted with the

accommodation regime.

Interviewees were found using snowball sampling and by

posting on the Facebook class pages for each year. The

focus of the research was on student experience and student

recommendations. All interviewees met the following criteria:

They were in enrolled at the law school for any part of 2011,

2012 or 2013;

They received accommodation, or requested

accommodation but were denied; and

They requested accommodation for physical illness or

injury; mental health; disability; care for ill relatives; or

bereavement.

Over the course of the year, 23 interviews were conducted.

The interviews were conducted primarily in person, but a few

students also sent in their comments via email.

The interviews were semi-structured. Care was taken to focus

on only relevant aspects of the students' experience as it related

to the accommodation request, rather than on the triggering

event. All recommendations are presented in the aggregate and

without attribution. We have not used any part of a students'

story which, even if presented without their name attached,

would risk identifying the student. This means that the report

focuses on recommendations for change rather than specifc

stories of student experience under the current system.

To ensure the confdentiality of our participants, the interview

notes were kept anonymous using a code system. All

participants were given an opportunity to read and validate this

report. Once that process was complete, the documents linking

their name to the code on the interview forms were deleted.

Methodology

3

Students were not able to clearly

express the rationales underpinning

the accommodation process.

Whatever the process, the goals of

accommodation should be clearly

articulated to students. While some

students felt that the goal of the OADS

was student success, others expressed

skepticism. Some sensed hesitation

from the OADS to accommodate them

out of fear that accommodations would

create unfairness or dilute the prestige

or quality of the degree. Students

sensed that some accommodations

were denied out of a fear that they

or other students were gaming the

system. Students emphasized the

accommodations system should not be

premised on the idea that students try

to cheat the system.

Equity does not mean treating all

students the same. Flexibility with

deadlines, course requirements and

overall workload does not dilute the

academic rigour of the degree or create

Themes

from

student

interviews

unfairness compared to other students.

An overly restrictive regime, which

denies legitimate accommodations in

order to prevent tricksters from gaming

the system, is not appropriate.

Recommendations

1. Clearly articulate the policy

rationales of the accommodation

process.

2. Identify and dispel myths about

accommodation creating unfairness or

diluting the degree.

3. Use these rationales to guide the

development of policy and respond to

accommodation requests.

4. Trust students, absent reason to

disbelieve them.

I. Rationales

4

There were two overarching themes in students perception

of the accommodation process. Students characterized the

process as driven by (1) a centralized decision-making power

in the OADS, and (2) a high degree of discretion. Students felt

that this approach has some advantages: accommodation can

be handled quickly; bureaucracy is kept to a minimum; and

accommodations can be tailored. However, there is a high

degree of risk that such a system will appear arbitrary or biased.

Students reported being unsure of whether they would receive

accommodation; some students decided it was better not to ask

for accommodation than face uncertain prospects of success.

This uncertainty exacerbated already stressful situations for

students.

Transparency would go a long way to remedy this perception.

Some students didnt know where to go when they had an

accommodations request. Some felt like they had to beg

the OADS, because all the information they could fnd about

accommodations online was that accommodation might be

available for very compelling personal circumstances or serious

illness, which did not help them to assess whether they might

be eligible. Students wished they had known which kinds of

situations are accommodated, the range of accommodation

options available for situations like theirs, and how the process

would unfold. They reported that they did not know what kind

of information to include in their request for accommodation.

Students understood the necessity of discretion, but want it

to be exercised within a clear policy framework and in a way

which resulted in better outcomes. Promotion of the facultys

accommodation process should therefore be detailed and

specifc. Descriptions of the accommodation process should

be part of an integrated communications strategy which

includes references to Accessibility Services, Counselling and

Psychological Services (CAPS) and discusses the warning signs

of common mental health issues.

Recommendations

5. Publish detailed policies

and guidelines that outline

the range of accommodations

typically ofered for a

particular accommodations

situation, with discretion

up (ie the guidelines should

represent a foor, not a ceiling).

6. Clarify routes of appeal.

II. Finding the right process

7. Publish anonymized

precedent of accommodations

provided to students.

8. Publish a list of information

that students seeking

accommodation should include

in their email requesting

accommodation.

9. Explain in detail during

Orientation Week what

students can expect.

10. Publish policies and

guidelines on the faculty

website.

11. Advertise CAPS every

time faculty mentions OADS

process.

12. Advertise Accessibility

Services every time faculty

mentions OADS process.

13. Enhance coordination

among Accessibility Services,

CAPS and OADS.

14. Teach frst year students

the warning signs of anxiety,

depression and exhaustion.

15. Work to de-stigmatize

mental health issues.

5

Students recommendations about

doctors notes

Students reported that getting a doctors note was a barrier

to getting accommodation. Students often did not realize

they needed such a note, and were asked by OADS to go back

and get one. With respect to mental health, some students

reported bad experiences with doctors who refused to believe

them. Others reported that feeling of shame or resentment

kept them from seeking professional help, which meant there

was no doctor to write a note. In at least some cases, students

were told that a general practitioner was insufcient, and that

a note from a specialist was required. Some students had a

doctors note, but were told to make another trip back to their

doctor to get a special form flled out. Some students do not

have a family doctor, which is also a barrier. As well, doctors

notes often have a fee associated, which can be a barrier for

students struggling with their fnances.

While a doctors note may be required when seeking

accommodation through Accessibility Services, a doctors note

should not be required in all circumstances within the Faculty

of Law. At a minimum, OADS should be fexible in the kind of

documentation it accepts. The requirement could be dropped

for either short term accommodations, or it could be dropped

for the frst two or three requests by a student, or both.

When students present to the OADS, they are often in acute

crisis. They do not know the full range of options available to

them, and they may not be clearly thinking about what they

need. They often felt scared to ask for a longer extension or

more accommodation, because they were afraid of being denied.

This meant students often ask for less than what they need.

Students reported considerable variation in their initial

interactions with the accommodation regime. Once their

request was accepted, some students were asked open-ended

questions like What would help you?, while others were given

a narrow list of options. Creative solutions advanced by students

were often treated with skepticism by the OADS in the initial

stages.

Some students also reported that they had received

markedly different treatment than classmates with a similar

accommodation request, both in the accommodation offered

and the amount of proof required. This led to a perception

among students that good students would receive more

generous accommodations.

Communications with students accessing the program must be

timely and compassionate. One of the strengths of the regime

is that the OADS often responds very quickly, even outside of

work hours. However, some students reported feeling they had

fallen through the cracks, with either communication or the

accommodation decision not communicated quickly enough.

III. Getting to the best individual outcomes

6

Waiting to fnd out whether they would be accommodated was

extremely stressful for some students.

The decision to accommodate should be communicated directly

to student as soon as possible. If possible, decision makers

should assess students likelihood of getting accommodation at

the outset.

The range of accommodations granted to students in seeking

accommodations in various circumstances should be publicly

available on the faculty website. The OADS should also clearly

communicate as wide a range of accommodations as possible

to the student. The OADS should support students and follow-

up to make sure the accommodation was enough, and new

problems havent emerged. Some students were offered

accommodations that were later reduced. This should not

happen; it makes it impossible for students to plan their work

and take the time they need to deal with whatever inspired the

accommodation request.

Accommodations should be driven by students needs.

Such an orientation would recognize a full range of life

circumstances that could form the basis of for accommodation.

Accommodations which are extremely short (such as deadline

extensions which are less than 24 hours) or which are

communicated very close to the deadline are less useful than

longer extensions granted well in advance. Students should be

encouraged to pick the arrangement which would most help

him or her. However, care should also be taken to remain open

to creative proposals by students.

Recommendations

16. Allow students' needs to guide process.

17. Present a full range of options to students on the faculty

website, and in person.

18. Encourage creative alternatives proposed by students.

19. Focus on long-term planning, not piece-meal

accommodation.

20. Recognize a full range of life circumstances as bases

for accommodation.

21. Recognize systemic problems, and compensate.

22. Communication with students in a timely and

compassionate manner.

23. Assess likelihood of getting accommodated at the outset.

24. Make decisions quickly and communicate decision

directly to student.

25. Follow up to check in.

26. Provide referrals.

7

Having a single point-person inside the faculty reduces stress.

Students appreciate that the point person is a senior administrator

empowered to make decisions without consulting other staff

or professors. However, some worried that the OADSs other

responsibilities could place the offce in a confict of interest.

For instance, if a student were critical of the administration,

they worried it might effect the outcome of an accommodation

request. Some students interviewed reported receiving markedly

different treatment than peers with similar problems, and worried

that this was related to the way the OADS perceived them. Some

students noted that the seemingly unlimited discretion held by

the OADS made it seem like they could not question or appeal the

accommodations they were offered.

Many students felt it might be better to have the point person

who was not the Associate Dean, or any other individual with

whom they had interactions in other areas of their law school

lives. Ideally, that point person would be a trained counsellor

who does accommodation at the faculty. If not, staff in the

OADSs offce should receive training about how to interact with

people in crisis and people with mental health concerns.

The single point person model does not preclude others

involvement. For instance, the OADS makes referrals to an

outside counsellor (who received positive reviews from our

informants). It would be helpful to have others from the faculty

involved: accommodation champions among the professors, an

alternate contact during vacations at the OADSs offce, and a

person to act in the case of an appeal of a decision of the OADS.

Some students also refected on the fact that they did not

know when they sought accommodation that it was sometimes

possible to get accommodation without divulging their

personal stories to the OADS, for instance by going directly to

CAPS or Accessability Services. For students who might be

uncomfortable discussing their mental health issues with staff

at the Faculty of Law, knowing about this option might be the

difference between seeking a needed accommodation or not.

Students should be made aware of the different pathways to

accommodation. While having a point person at the faculty is

IV. Role of the Ofce of the Assistant Dean of Students

Recommendations

27. Maintain the single point-

person model, but make clear

that there are other pathways

that students can opt into

through CAPS and Accessibility

Services.

28. Hire a trained counsellor

to do accommodation at the

faculty.

29. Train staf to deal with

people in crisis and people

with mental health concerns

appropriately.

30. Identify accessibility

champions among professors.

31. Make outside counsellor

more available.

32. Identify a point person

during OADS vacations.

33. Add courses to ROSI before

beginning of semester.

34. Copy students on all

emails between faculty and

Accessibility Services about

them.

8

useful, there may be cases where an

alternative pathway makes necessary

accommodations more accessible.

It is important that there be strong

links between the OADSs offce, CAPS

and Accessibility Services. Students

reported that technical problems (like

delays by the faculty in adding courses

to ROSI) prevent students from getting

the full beneft of some Accessibility

Services accommodations. If the single

point-person model continues at the

faculty (compared to other colleges,

where Accessibility Services staff

contact professors), care must be taken

to make sure accommodation updates

are promptly conveyed to professors,

in consultation with the affected

student.

Finally, many students recognized

how hard the Assistant Dean worked

to respond to accommodation

requests in a timely fashion.

However, she is only one person and it

is inevitable that given all her other

responsibilities some students

found her hard to reach or schedule

appointments with.

There are already projects

underway to address mental health

and wellness at the law school.

This report does not intend to

duplicate the work being done in

that regard. Still, students noted

that, with respect mental health

accommodations, the structure of

the law school (the 1L curriculum,

competitiveness, 100 percent

fnals) exacerbates the need to

provide accommodation. As well,

the law schools attitude toward

accommodation has ramifcations

for students later practice. The

Faculty of Law must be careful

not to send messages about

accommodation which teach people

not to reach out for help once they

are members of the legal profession.

Accommodations can have

signifcant fnancial ramifcations

for students, which should be

considered as part of a holistic,

student-centred approach to

accommodations. Administrators

of the accommodations program

should be sensitive to the

sometimes precarious fnancial

situation of students seeking

accommodation. Students who

withdraw, defer or reduce their

courseload should have their tuition

fees refunded, or should have their

tuition waived the subsequent year

if they decide to re-enrol. The OADS

should recognize and compensate

for the fnancial costs of doctors

notes. And students should be

directed to the bursary program

at Accessibility Services for health

needs which fall outside of the

ambit of public insurance and the

University of Toronto health plan.

V. Addressing structural issues

Recommendations

35. Address the systemic

and structural aspects of law

school which contribute to

poor mental health outcomes.

36. Address fnancial

stresses which arise from the

accommodation system.

9

Students who have accessed or tried to access the accommodation

system are a wellspring of advice for other students. However, not all

students have broad peer supports from which to learn about their

peers experiences. Students we interviewed offered advice for others

entering the accommodation system (see below). Such advice should

be collected and provided by a third party, such as the Student Law

Society Equity Offcer or another ombudsperson.

Advice from students to students:

Types of accommodation

Here are some of the types of accommodation currently given to

students:

Flexibility with deadlines (including into Summer term)

Changing course requirements (like not requiring participation)

Eliminating attendance requirement

Creative proposals put forward by student

Assistance: note taking

Longer exam writing times, writing in a special room

Aegrotat grades

Part time (with refund)

Withdrawal (with refund)

Additional accommodations the Faculty could start ofering

Let students take one less class, make it up a subsequent semester

Having a course/courses/independent study available during

summer term

Ability to re-write an exam or paper

Coda: For students navigating the current system

Don't wait until a crisis is

acute to ask for help.

Go to Accessibility Services

or CAPS right away; don't

wait for Faculty process to

fail.

Look into Accessibility

Services bursaries for

counselling or other needs.

Contact Accessibility

Services if you need

accommodations in writing a

provincial Bar Exam.

Bring a friend or the SLS

Equity Ofcer to meetings.

Communicate in writing or

take notes at meetings.

In initial email to the OADS,

include: your situation, how

long you spent dealing with

it, what you expect, and

questions you have.

If your email is urgent, label

it URGENT.

Follow up if the process is

going too slowly, or if you're

not getting the right result.

10

Вам также может понравиться

- Dash 3Документ9 страницDash 3Dashielle GalangОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Status of Panchayati Raj State Profile - Madhya PradeshДокумент29 страницStatus of Panchayati Raj State Profile - Madhya Pradeshnishat khanОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Pharmaceutical Sector in PakistanДокумент15 страницPharmaceutical Sector in PakistanAamir Shehzad100% (1)

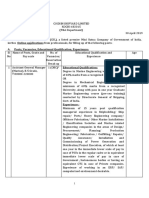

- Posts, Vacancies, Educational Qualification, ExperienceДокумент7 страницPosts, Vacancies, Educational Qualification, ExperienceRajesh RajОценок пока нет

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- August 2020Документ166 страницAugust 2020ARGHA PAULОценок пока нет

- Siniloan Tourism CodeДокумент34 страницыSiniloan Tourism CodeMark Ronald ArgoteОценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Jiabong Samar - The Mussel Capital PDFДокумент3 страницыJiabong Samar - The Mussel Capital PDFsamdelacruz1030100% (1)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- GXP and CGXP in Bio-Pharmaceuticals IndustryДокумент8 страницGXP and CGXP in Bio-Pharmaceuticals IndustryoutkastedОценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- List of All Central Government SchemesДокумент13 страницList of All Central Government Schemeskachana srikanth ReddyОценок пока нет

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Environmental Management System: Standard Operating ProcedureДокумент4 страницыEnvironmental Management System: Standard Operating ProcedureMohammed AffrozeОценок пока нет

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Closed PTW AuditДокумент1 страницаClosed PTW Auditf.BОценок пока нет

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Final Practice QuestionsДокумент5 страницFinal Practice QuestionsAnhОценок пока нет

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- 6079 Clinical Leadership A Literature Review To Investigate Concepts Roles and Relationships Related To Clinical LeadershipДокумент18 страниц6079 Clinical Leadership A Literature Review To Investigate Concepts Roles and Relationships Related To Clinical LeadershipLidya MaryaniОценок пока нет

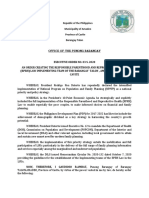

- IRR Magna Carta of Women Presentation For LaunchДокумент27 страницIRR Magna Carta of Women Presentation For Launchyaniegg100% (1)

- Brockton Schools AuditДокумент4 страницыBrockton Schools AuditBoston 25 DeskОценок пока нет

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Cabin Crew Declaration Form - Ver 2.0Документ3 страницыCabin Crew Declaration Form - Ver 2.0Sarah BoussaadiaОценок пока нет

- Barangay RPRH-LawДокумент3 страницыBarangay RPRH-LawelyssОценок пока нет

- Field Trip Policy - Waiver.docx - One PageДокумент1 страницаField Trip Policy - Waiver.docx - One PageJoshua RomeaОценок пока нет

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- 49cfr Shipping Hazardous MaterialsДокумент52 страницы49cfr Shipping Hazardous MaterialsJody100% (1)

- Internal and External Vacancy Announcement (State Team Lead)Документ2 страницыInternal and External Vacancy Announcement (State Team Lead)Phr InitiativeОценок пока нет

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Progressive Expanded Face To Face Class Program: Grade 1 and Grade 2Документ3 страницыProgressive Expanded Face To Face Class Program: Grade 1 and Grade 2Annelet Pelaez TolentinoОценок пока нет

- Hon. Oscar C. Villegas Jr. Mayor Lemery, Iloilo Dear Mayor VillegasДокумент1 страницаHon. Oscar C. Villegas Jr. Mayor Lemery, Iloilo Dear Mayor VillegasJulius Espiga ElmedorialОценок пока нет

- OSHA 2232 - Longshoring IndustryДокумент291 страницаOSHA 2232 - Longshoring IndustryWahed Mn ElnasОценок пока нет

- Security Sector ReformДокумент10 страницSecurity Sector ReformCeliaОценок пока нет

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Executive Rule For CME - PD - SCFHSДокумент14 страницExecutive Rule For CME - PD - SCFHSsevattapillaiОценок пока нет

- Duterte Health Agenda V 7-14-16Документ17 страницDuterte Health Agenda V 7-14-16Marione Thea Rodriguez100% (3)

- RMC No. 14-2021Документ1 страницаRMC No. 14-2021nathalie velasquezОценок пока нет

- S20157enДокумент137 страницS20157enrgrao85Оценок пока нет

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Nathan e Lensch vs. Sophia Rutschow 14-3-03127-0Документ165 страницNathan e Lensch vs. Sophia Rutschow 14-3-03127-0Eric YoungОценок пока нет

- DPV 2052 Health, Safety and EnvironmentДокумент15 страницDPV 2052 Health, Safety and EnvironmentXavier Scarlet IVОценок пока нет