Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Popa-radu-i6070269-Economic Studies-Interest Rate Pass-Through in Czech Republic 2004-201

Загружено:

Radu PopaОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Popa-radu-i6070269-Economic Studies-Interest Rate Pass-Through in Czech Republic 2004-201

Загружено:

Radu PopaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The interest pass-through in the Czech Republic

2004-2014

RaduPopa i6070269

Maastricht University

School of Business and Economics

Master of Economic Studies

Supervisor: Prof. dr. Bertrand Candelon

J une 2014

Abstract

This paper examines the impact of the policy rate on deposit and loan rates in Czech Republic

between 2004 and 2014. An error correction model, will be used if cointegration is found.

Alternatively, a first difference ARDL model will be used if no cointegration is found. Bank

rates will be regressed to the policy rate and to the money market rate with which they have the

highest correlation. Lastly, a rolling regression will be utilized in order to find structural breaks

endogenously and observe the gradual impact of the crisis on the pass-though.

For the period leading up to 2009, loans to non-financial corporations have a full pass-through,

mortgages follow with a long run pass-through of 70%, and no significant impact is found for

consumer credit loans, credit cards and household overdrafts. The impact of the crisis has been

more pronounced for the household sector, making the pass-through insignificant for household

loans. However the pass-through for non-financial corporations has been less affected by the

financial crisis, but has substantially diminished since the end of 2012, as the policy rate has

reached the zero lower bound.

1

Contents

1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 2

2. Literature review ............................................................................................................................. 3

2.1 Determinants of the interest rate pass-through ................................................................................ 3

2.2 Interest rate pass-through in the Czech Republic ............................................................................ 6

2.3 Impact of the financial crisis .......................................................................................................... 9

3. Methodology ................................................................................................................................. 10

4. Data description ............................................................................................................................. 11

4.a) Money market rates .................................................................................................................... 13

4.b) Government bond yields ............................................................................................................. 14

4.c) Household deposits ..................................................................................................................... 15

4.d) Non-financial corporations deposits ............................................................................................ 17

4.e) Household loans ......................................................................................................................... 19

4.f) Non-financial corporations loans ................................................................................................. 21

5. Results ........................................................................................................................................... 22

5.a) Money market rates................................................................................................................. 22

5.b) Government bonds .................................................................................................................. 23

5.c) Household deposits ................................................................................................................. 25

5.d) Non-financial corporations deposits ........................................................................................ 27

5.e) Household loans...................................................................................................................... 29

5.f) Non-financial corporations loans ............................................................................................. 31

6. Conclusion .................................................................................................................................... 32

Bibliography ......................................................................................................................................... 35

Appendix .............................................................................................................................................. 38

Appendix A Unit root test results ................................................................................................... 38

Appendix B Cointegration test results- monetary approach............................................................. 41

Appendix C Bond correlation........................................................................................................... 43

Appendix D Cointegration test results -cost of funds method............................................................ 44

Appendix E Results monetary approach ......................................................................................... 45

Appendix F Results cost of funds approach .................................................................................... 51

Appendix G Rolling regression cost of funds approach ................................................................... 55

2

1. Introduction

One of the most important tools of a central bank is the interest rate channel through which

changes in the policy rate are transmitted to bank rates of households and firms. Bernanke and

Blinder (1992) have proven that monetary tightening decreases availability of credit and

negatively impacts credit. Gertler and Gilchrist (1994) have focused specifically on small firms,

showing inventory investment is sensitive to higher policy rates. Therefore analyzing the impact

of central banks on lending and deposit rates is vital in order to be able to gauge the efficiency of

central bank policy on the real economy.

Yet the recent financial crisis has cast a large doubt on the power of central banks to steer the

economy and jump start a recovery. While much of the focus has been on Western Europe and

the Euro area, the impact that the crisis has had on monetary policy in Eastern and Central

Europe has mostly been neglected by mainstream academia. Therefore, this paper will extend

this type of analysis to the Czech Republic, focusing on the period between 2004 and 2014. The

latest study on the interest rate pass-through in the Czech Republic was published in 2009,

therefore this paper will bring novel data about the developments of the interest rate pass-through

in the aftermath of the financial crisis.

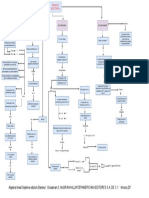

Given the I(1) nature of interest rates, cointegration will be tested using the J ohansen trace

statistic in order to see whether a long run relationship exists. If cointegration is found, an error

correction model will be employed, otherwise an ARDL model of first differences will be used.

Bank rates will be regressed to the policy rate, in accordance with the monetary policy approach

used by Sander and Kleimeier (2004), and to the money market rate with the highest correlation,

following the cost of funds approach supported by De Bondt (2005). Due to the possible

existence of a structural break in the data, results will be estimated for the period prior to August

2008 and afterwards. Finally, a rolling regression with a window of 50 months will be used, thus

presenting the gradual evolution of the pass-through since 2009 and finding additional structural

breaks endogenously.

The paper will be structured as follows: section 2 will present a literature overview of the theory

behind the determinants of the interest rate pass-through, the evolution of the interest rate pass-

through Czech Republic and an analysis of how the financial crisis has impacted the pass-

through in Western Europe. Section 3 will present the methodology. Section 4 will begin with a

description of the macroeconomic environment in Czech Republic over the past 10 years,

followed by a summary of the analyzed deposit and loan rates. Section 5 will present the results

for the monetary policy approach, including a graphical presentation of the long run coefficient

for the rolling regression. Graphs and detailed tables for the cost of funds approach are available

in the appendixes. Finally, section 6 will present the conclusions.

3

2. Literature review

2.1 Determinants of the interest rate pass-through

As banks can gain funding from money markets, consumer deposits or capital markets, yields are

expected to equalize of between the different markets as any opportunity to access funds at a

lower costs will be exploited, thus driving yields up. Therefore money market rates can be

regarded as a proxy for the cost of funding. As a result, a change in the policy rate should impact

the interest banks charge to customers as they maintain a constant mark-up over market rates.

On the other hand, consumers to place their savings in money market funds, bank deposits or

government bond yields. Thus money market rates represent an opportunity cost for savers. In a

model with perfect competition and no switching costs, the demand elasticity of deposits would

be 1 as yields across different asset markets equalize, thus entailing a complete pass-through

from monetary policy to deposit rates.

De Bondt (2005) describes the transmission mechanism from policy rate to interest rates for

consumers and firms in a two stage manner. In the first stage, the central policy rate impacts the

short term money market rates. The two-week repo acts as an opportunity costs for banks, it is

expected that money market rates will not exceed the policy rate. While variations occur on a

daily basis due to liquidity shortages in the market and reserve requirements, in the long run,

money market rates and the policy rate move together. In the second stage, long term rates in

money market are impacted, therefore a proportionate transmission of the policy rate implies a

parallel shift in the yield curve. If one of the factors affecting the yield curve changes, such as

inflationary expectations, liquidity premiums for long term maturities or market segmentation;

then the transmission of the policy rate will not be proportionate.

As opposed to the cost of funds approach, the monetary approach focuses solely on the

relationship between the policy rate and retail lending rates, thus assuming a constant yield

curve. Such an estimation method is preferable due to its simplicity and is extremely useful if

cointegration between money rates and lending/deposit rates is not found.

De Bondt (2005) uses the marginal cost pricing model br =

0 +

1

*mr wherebr is the bank rate,

0

is the constant markup,

1

is the demand elasticity of deposits or loans andmr is the market rate.

A demand elasticity of 1 would occur in a model with perfect competition, no switching costs

and information asymmetries, thus entailing a complete pass-through from monetary policy to

deposit rates. Nevertheless, such a situation does not occur in reality, therefore many deposit and

loan rates have a pass-through lower than 1

The degree of competition between banks is very important determinant in the elasticity of

deposits. If there are relatively few banks, they can collude and will not feel pressure to adjust

rates rapidly. On the other hand, if there are a large number of banks, once one bank will adjust

their rates, others will have to follow suit for fear losing customers to the competition. Van

Leuvensteijn, Kok Sorensen et al. (2008) analyze the impact of competition on the interest rate

4

pass-through for 8 Euro area countries for the period 1994-2006

1

. They measure competition

with the Boone indicator, which measures the elasticity of profits to marginal costs

2

. Their

findings show that higher competition leads to lower spreads between money market rates and

lending rates. Furthermore, the impact of competition lowers deposit rates, as banks compensate

lost revenue from lending by cutting interest rates paid on deposits. Overall, a higher degree of

competition is associated with a larger and more rapid pass-through for both lending and deposit

rates.

When cost of funding goes up, banks have the incentive to pass on the additional costs to

customers. On the other hand, when costs fall, banks will postpone decreasing lending rates as

they can benefit from a higher margin. Mojon (2000) looks at interest rates for the six largest

economies of the Eurozone between 1979-1998. He shows that the pass-through is higher when

money market rates increase, while rates adjust slower when money market rates are decreasing.

This downward rigidity leads to an asymmetric speed of adjustment for lending rates.

Furthermore, the impact of regulation, as measured by Gual, (1999), is shown to be significant

only when money market rates are decreasing, therefore reducing this downward rigidity. The

opposite effect is observed for deposits ie deregulation increases the pass-through when money

market rates are increasing. Therefore, a higher degree of competition is expected to minimize

the asymetry of the pass-through for both lending and deposit rates.

If companies rely heavily on financial markets, ie bonds issuance, in order to raise funds, they

will be less impacted by developments in the money market. Furthermore, the development of

money market funds and mutual funds has increased competition for traditional deposits and

improved alternatives for savers. The process of financial disintermediation implies a lower

dependency on banks for funding and a higher reliance on capital markets. Access to direct

finance outside of the bank sector is expected to increase the pass-through as it puts more

pressure on banks to offer competitive rates to clients. Singh, Razi et al., (2008)analyze the

interest rate pass-through in developed and developing Asian countries, controlling for financial

market developments across countries. They have found a positive correlation between the size

of equity and bond markets and the size and speed of the interest rate pass-through. Furthermore,

more developed financial markets also improve the pass-through to short term and long term

government bond yields.

Ozdemir and Altinoz (2012) use the z-score as one of the determinants for the size for interest

pass-through in 25 emerging country economies between 2004 and 2008. The z-score is defined

as the sum of the mean return on assets and ratio of equity to assets by the standard deviation of

return on assets for banks in the respective country. Therefore, a higher z score reflects a higher

buffer against future losses and a healthier banking sector. The authors find a positive

relationship, thus a 1 point increases in the z-score improves the pass-through by 15%.

1

The countries analyzed are: Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain

2

The market share of more efficient banks is expected to increase as competition increases. A larger negative value

indicates a higher market share of companies with lower marginal costs, and thus a higher degree of competition

5

The bank finance structure also impacts the extent to which it transfers changes in policy to

consumers. A bank which would be highly reliant on external funds from money market will

immediately feel the pressure from a change in the policy rate. On the other hand, a bank which

has a substantial amount of long term deposits will not have such a pressure to reprice its loans

as its deposits will adjust their interest rates less frequently. Gambacorta (2005) looks at the

impact of monetary policy on Italian banks between 1986-2001, showing that more liquid banks

are less responsive to a monetary policy shock. Furthermore, banks with higher levels of capital

will be less affected by monetary policy as they can access alternative sources of funding such as

capital markets. J imborean (2009) analyzes data from individual commercial banks from 10

Central European countries between 1998-2006

3

. By separating banks depending on their loan to

deposit ratio, the author finds that lending growth for banks with a high deposit to loan ratio is

not impacted by a monetary policy shock. Weth (2002) looks at the maturity mismatch between

loans and deposits, showing that banks which have a larger proportion of short term deposits to

fund long term loans, will have a higher pass-through.

While large firms have access to capital markets to obtain funding, SMEs and households are

highly reliant on bank financing, therefore lending rate need to not fully adjust. Therefore, the

pass-through for corporate loans is expected to be closer to 1 due to competition from financial

markets and higher credit-worthiness of large firms. For example, Sander and Kleimeier (2004)

show that the interest rate pass-through in 8 Central European countries between 1993 and 2003

is 91% for short term corporate loans, 107% for long term corporate loans, but only 59% for

consumer loans. Furthermore, Van Leuvensteijn, Kok Sorensen et al. (2008) show that an

increase in the Boone indicator, a measure of competition, has a the highest impact on short-term

corporate loans, while mortgage loans, followed by consumer credit, present a lower

responsiveness to changes in competitiveness.

Furthermore, switching costs, both administrative and informational, also act as a deterrent for

customers for customers to move to another bank in order benefit from a higher deposit rate.

Kim, Kliger et al. (2003) show that contractual penalties for loans impose high costs for ending

the relationship prematurely, thus locking in customers for years. Therefore lower switching

costs increase the elasticity of demand, making it more likely for rates to adjust faster.

Due to asymmetric information, banks are not able to exactly determine the probability of default

for firms. Banks will charge higher risk premiums when increasing rates in order to cover the

adverse selection (attracting lower quality borrowers) and moral hazard (borrowers use loans for

ventures with higher returns, and thus higher risks, in order to be able to pay back higher

interest).Stiglitz and Weiss (1981) showed that banks will not raise rates proportionally and will

ration credit only to eligible client, if they believe that profits of higher interest rate income will

be outweighed by defaults .On the other hand, a pass-through higher than one implies that banks

are willing to lend to riskier ventures and are not involved in credit rationing.

3

Countries analyzed are Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovak

Republic and Slovenia.

6

Sander and Kleimeier (2004) analyze the impact of money market volatility and inflation rates

on the pass-through. Money market volatility has a negative impact as it makes it hard for banks

to differentiate white noise from long run trends in the money market rates. Therefore banks will

choose to implement larger adjustments at longer intervals. On the other hand, higher inflation

has a positive impact on the pass-through as shown by Mojon (2000). During periods of high

inflation, with a 1% higher inflation decreases the pass-through by 6% as price adjustments for

firms occur more frequently, therefore banks can pass on higher costs with greater ease. Last but

not least, higher economic growth is expected to improve the pass-through as shown by Sander

and Kleimeier (2004). According to their estimates, 1% higher GDP growth improves the pass-

through by 17%.

2.2 Interest rate pass-through in the Czech Republic

Sander and Kleimeier (2004) account for differences between effectiveness of monetary policy

by focusing on the financial structure(bank concentration, foreign bank ownership), financial

development (credit to GDP, non-performing loans, stock market capitalization) and

macroeconomic developments such as volatility of money market rates and inflation. While

GDP growth and financial development are not significant, inflation has a positive sign,

therefore a higher rate of inflation is expected to increase the size and speed of the pass-through.

On the other hand, money market volatility as measured by standard deviation of 1-month

money market rate has a negative coefficient. They find an average pass-through for loans

increasing from 78% for period 1993-1997 to 95% for the period 1999-2003. The pass-through

for deposits is lower, starting at 44% for the period 1993-1997 and increasing to 66% between

1999-2003. Out of the sample of countries, Czech Republic dummy is not statistically

significant, therefore results are in line with other countries analyzed.

gert, Crespo-Cuaresma et al. (2007) use the monetary and cost of funds approach to analyze the

pass-through in 5 Central European countries between 1995 and 2005. The monetary approach is

estimated by using a bivariate error correction model linking the market rate to the policy rate is

estimate using both Dynamic Ordinary Least Squares and Autoregressive Distributed Lag model.

Overall stock of deposits in Czech Republic has a coefficient of 80% for maturity less 1 year

and70% for maturity higher 1year. Lending rates for the total stock of loans with maturities up to

1year have a pass-through of 66%, while total household loans have a statistically insignificant

pass-through. Looking at the period between 2001 and 2005, the pass-through for non-financial

corporations loans is 87% for loans with maturity up to 1 year and 98% for loans with a maturity

between 1 and 5 years. A cointegration relationship is found only for Czech Republic between

2001 and 2005, supporting the cost of funds approach two stage approach. The coefficients

yielded through this estimation method are consistent with the monetary policy approach: 73%

for deposits up to than 1 year and90% for non-financial corporate loans with maturities between

1 and 5 years.

Tieman (2004) also look at the period 1995-2004, focusing on Czech Republic, Hungary,

Poland, the Slovak Republic, and Slovenia. The author employs a bivariate Error Correction

model, following the monetary policy approach. Adding to gert, Crespo-Cuaresma et al.

7

(2007), data is also available for new loans for the period 2001-2004. Stock of short term

deposits have a pass-through of 79%, while long term deposits have a lower long term pass-

through of 49%. Regarding loans, short term maturities exhibit a higher responsiveness to

changes in the policy rate as the pass-through is 104% for newly issued short term loans, while

for long term loans the coefficient declines to 83%.

The following table from Coricelli, gert et al. (2006) provides a useful overview of the pass-

through in Central and Eastern European countries, as measured by studies 1998 and 2004.

Long-Run Interest Rate Pass-Through Estimates for the CEECs

Type of rate Average long-run pass-through

Short-term deposit rate 0.72

Long-term deposit rate 0.69

Short-term lending rate 1.01

Long-term lending rate 0.91

Consumer lending rate 0.51

Housing/mortgage lending rate 0.73

Horvth and Podpiera (2012) look at the pass-through in Czech Republic between J anuary 2004

and December 2008, applying panel cointegration technique to a panel of bank data. They allow

for heterogeneity in both the speed of adjustment and the size of the pass-through. The results

were obtained by analyzing bank data and presenting median values of the pass-through out of

the sample. They used a single equation bivariate error correction model, regressing bank rates

on the money market rate with the highest correlation. Compared to previous studies, short term

deposits show an improvement, coming closer to a full pass-through with a full coefficient of

93%. On the other hand, long term deposits are below the CEEC average with a pass-through of

47%. Regarding mortgage loans, the pass-through is significant with a coefficient of 62%, but

slightly lower compared to CEEC average. Lastly, loans for non-financial corporations bellow 30

mio CZK exhibit a full pass-through for all maturities, while loans above 30 mio CZK have a

coefficient of around 80%. This is counterintuitive as we would expect larger loans to have a

larger pass-through due to higher credit-worthiness of borrowers and larger elasticity of demand

given existence of other financing alternatives.

8

Households

Short-term pass-

through

Long-term pass-

through

Speed of

adjustment

Deposits

With agreed maturity of up

to two years

0.70*** 0.93*** - 0.61***

(0.09) (0.02) (0.09)

With agreed maturity of over

two years

0.68 0.47*** - 0.28*

(0.63) (0.06) (0.14)

Loans

Lending for house purchase - 0.13 0.62

***

- 0.34

***

(0.23) (0.03) (0.11)

Non-financial corporations - Loans up to CZK 30 mil

Floating rate and initial rate

fixation of up to one year

0.70

**

0.94

***

- 0.50

***

-(0.15) (0.06) (0.11)

Initial rate fixation of over

one year

0.52 0.95

***

- 0.49

***

(0.44) (0.09) (0.20)

Non-financial corporations - Loans over CZK 30 mil

Floating rate and initial rate

fixation of up to one year

0.90

***

0.81

***

- 0.53

***

(0.30) (0.03) (0.10)

Initial rate fixation of over

one year

0.9 0.78

***

- 0.77

***

(2.20) (0.08) (0.27)

Furthermore, their dataset allows them to study what the determinants are for differences in the

pass-through within banks. While banks react heterogeneously in the short run, in the long run

their coefficients are homogenous. They find that banks which rely heavily on deposit funding as

opposed to non-deposit funding will tend to have a lower pass-through as they will smoothen the

transition to their customers and rely more on relationship lending. Credit risk, as measured by

non-performing loans, has a positive effect on the interest rate pass-through. Therefore banks

which experience higher credit risk will not have the adequate resources to smoothen the

transmission of a policy shock to their customers. Other indicators such as bank size, capital

adequacy and liquidity do not affect the interest rate pass-through.

Babeck-Kucharukov, Franta et al. (2013) extend the analysis to 2009, find that the pass-

through short term deposits has remained constant, while that for long term deposits has

9

increased to 73%. Mortgages have also increased, having a long term coefficient of 92% as

opposed to 62% before. Regarding non-financial corporations, the crisis has had a negative effect

for loans with an interest rate fixation period below 1 year and a positive effect for loans with a

higher interest rate fixation period. This effect has been more pronounced for smaller loans

(around 20% in both directions), while for larger loans it has only been around 1-2 percentage

points.

The main conclusions from surveying the data are: corporate loans have higher pass-through

than consumer loans, as expected given that corporations have access to other sources of funding

such as capital markets. Long term deposits have a higher pass-through than short term deposits,

while current account and saving accounts show a very low pass-through. Lastly, a large degree

of heterogeneity is observable within countries, with Czech Republic having a slightly lower

pass-through than other countries in the region.

2.3 Impact of the financial crisis

Beckmann, Kleimeier et al. (2013) look at the impact of banking crises on the interest

rate pass-through. They use a database set up by Laeven and Valencia (2013)which covers

banking crisis from the 1980s onwards. Given that the current financial crisis is still developing,

the results do not allow for estimation post crisis. Nevertheless, they find that the long run pass-

through in France, Germany, Ireland and UK has not been affected by the crisis. On the other

hand, for Italy, Portugal and Spain the financial crisis has decreased long run pass-through by 30

to 70 percentage points. Regarding deposit rates, the impact has been even larger as the pass-

through has declined from a full pass-through to insignificant for Spain and Portugal. UK and

Germany have also been impacted, falling by around 20 percentage points for Germany and 60

for UK.

ECB (2013) analyzes the impact of financial fragmentation on the pass-through after the

crisis. Due to sovereign debt crisis and the slowdown of economic activity, the decreases in the

policy rate could have not been passed down to firms as banks require higher premium over the

policy rate in order to be compensated for the higher risk of default. Furthermore, since the

beginning of the crisis, the spread between lending rates has increased, especially for smaller

loans designated for SMEs, showing the flight to quality of banks. This situation was especially

pronounced in Spain and Italy, both countries severely affected by recession and sovereign debt

crisis. In addition to this, changes from the policy rate were transmitted quite uniformly for the

policy rate cuts between October 2008 and May 2009, but much more heterogeneously and

incomplete for those between November 2011 and J uly 2012. For example, short term lending

rates to household increased in Spain and Ireland over the period even though the policy rate fell.

Overall, they find that the increase in sovereign bond yields spread to German bonds as well as

other macroeconomic factors such as high unemployment, increased probability of default for

non-financial companies are responsible for the discrepancies within countries.

Al-Eyd and Berkmen, (2013) extend the traditional ECM model by including variables

which capture changes in macroeconomic environment which might affect the pass-through and

explain the recent divergence between core and periphery countries. When controlling for factors

10

such as CDS spreads for financial companies, spread of bank bonds to the policy rate and asset to

capital, the pass-through is unchanged compared to pre-crisis period. Therefore the heterogeneity

between core and periphery countries and elevated lending rates can be explained by

developments related to macroeconomic environment rather than traditional determinants of the

interest rate pass-through such as competition or bank finance structure.

3.Methodology

According to the monetary approach, the long run relationship between the policy rate and bank

rates isBR

t

=0

0

+0P

1

+u

t

. As stationarity is an issue with interest rate time series, unit root

tests augmented Dickey Fuller (ADF), Phillips Perron (PP) and Kwiatkowski-Phillips-

Schmidt-Shin (KPSS) will be performed. Cointegration between two variables means that

despite fluctuations in the short run, these values will not deviate from equilibrium for an

extended period of time. Cointegration will be tested using the Johansen trace statistic and the

optimal lag length will be determined by the Akaike Information Criterion with maximum

number of lags set to 4.

If cointegration is found, then an error correction model used to estimate the pass-through as

shown below

BR

t

=o + [

BR,

BR

t-

k

=1

+ [

P,

P

t-

n

=1

+0ECI

t-1

+e

t

where BR is the retail bank rate for deposits or loans, P is the monetary policy rate and the error

term is ECI

t-1

=P

t-1

[

BR,t-1

BR

t-1

. The short run impact of a policy rate shock is[

BR,1

,

the long run impact is

[

P,t-i

n

i=1

1- [

BR,t-i

k

i=1

and the speed of adjustment is0.The advantage of the ECM

is that it gives the possibility to differentiate between short run and long run dynamics, thus

giving a complete picture of the interest rate pass-through.

If no cointegration relationship is found, then an ARDL model will be estimated as shown below

BR

t

=o +[

BR,0

BR

t

[

BR,

BR

t-

k

=1

+ [

P,

P

t-

n

=1

In this case, the short run impact of a policy rate shock is [

BR,1

, the long run impact is

[

P

n

i=1

1- [

BR,t-i

k

i=0

and the speed of adjustment is[

BR,0

as defined by Sander and Kleimeier (2004). A

speed of adjustment lower than 1 shows that the impact of a change in the policy rate is

transmitted to market rates within one month.

Given the possible existence of a structural break since the onset of the crisis, the J ohansen trace

statistic may wrongly indicate lack of cointegration due to the misspecification of the model

Therefore, cointegration tests will also be performed for period before August 2008 and

afterwards and the ECM will be estimated separately for pre-break and post break period. The

date was chosen as it was the first month when the Czech National Bank started cutting its policy

11

rate in response to the financial crisis in Europe, therefore it provides the first signal of the

change in the macroeconomic environment.

Lastly, a rolling regression with a period of 50 months will be conducted in order to gauge how

the long run coefficients have changed since 2008. A period of 50 months was chosen in order to

give a clear estimate of the pass-through before the crisis and show the gradual impacts of the

economic crisis. If cointegration is found in at least two of periods analyzed (full period, before

or after crisis), then an error correction model will be employed. Otherwise, an ARDL model

will be used. The results will be presented by graphing the long run impact along with its 95%

confidence interval.

Additionally, the cost of funds method will be used to measure the pass-through. Given the short

maturity of the policy rate, it may not be a useful indicator to measure to opportunity costs for

banks in the case of loans with longer maturities. Therefore the cost of funds approach defines

the pass-through from the policy rate to bank rates as a two stage process: initially from the

policy rate impacts market rates, and afterwards, from market rates to bank rates. For example,

De Bondt, Mojon et al. (2005) find that bank will set rates for long term loans such as mortgages

in accordance to long term liabilities such as government bonds. Therefore the market rates

analyzed will be interbank money rate rates with maturities of 1 day, 1 month, 3 months and 1

year and government bonds with maturities of 2 years, 5 years and 10 years. The market rate

with the highest correlation will be chosen and the same methodology as the monetary approach

will be used to measure the pass-through from market rates to the bank rate.

4. Data description

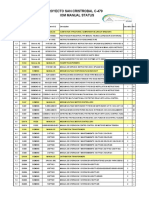

The period between 2004 and 2006 is characterized by high GDP growth fuelled by

increasing household and business debt. Growth in the EU helped boost Czech exports as well as

foreign direct investment. Furthermore, low oil prices helped inflation fluctuate around 2% level.

Therefore the policy rate remained around the 2% level, supporting economic growth. During

2007 as international tensions started to mount due to the developing financial crisis in the

United States, the Czech Republic was not affected as GDP continued to grow at an accelerated

pace, along with exports and household debt. However, increasing oil prices along with a VAT

tax hike put pressure on the inflation rate, thus forcing the Czech National Bank to increase the

policy rate by an entire percentage point during 2007 from 2,5% to 3,5%(CNB 2008). Another

increase followed in February 2008, yet as inflationary pressures fell and the economic

slowdown of developed countries in EU started to affect Czech economy, the Czech National

Bank decided to decrease the policy rate in August 2008to 3,5%. By the end of the year, the

policy rate fell further to 2,25%. The performance of the economy was disappointing in 2009

registering the first year of negative economic growth with a record high government deficit and

a drastic fall in exports, even though the Central Bank further eased monetary policy, lowering

the policy rate to 1%(CNB 2009).

12

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013

GDP growth 4,7 6,8 7,0 5,7 3,1 -4,5 2,5 1,8 -1,0 -0,9

Loan growth households 33,0 32,6 29,5 34,4 21,2 11,7 7,5 5,8 4,0 3,7

Loan growth non-

financial corporations

8,0 15,6 19,6 19,5 12,3 -8,2 0,0 5,3 2,5 -1,6

Non-performing loans 6,3 5,0 4,2 3,4 3,1 4,8 6,7 7,0 6,5 6,6

Export growth 16,0 16,5 17,5 13,6 10,5 -15,7 19,1 13,5 5,3 -1,5

Government deficit -2,8 -3,2 -2,4 -0,7 -2,2 -5,8 -4,7 -3,2 -4,2 -1,5

Unemployment 8,3 7,9 7,1 5,3 4,4 6,7 7,3 6,7 7,0 6,9

Inflation 2,6 1,6 2,1 3,0 6,3 0,6 1,3 2,1 3,5 1,4

Policy rate 2,3 1,9 2,2 2,9 3,5 1,5 0,8 0,8 0,5 0,1

All figures are percentages

Property prices started falling as well, as growth in mortgages subsided and supply of new

residences outstripped demand. Nevertheless, the high profitability of the banking sector,

comfortable deposit to credit ratio and low proportion of foreign currency loans were important

factors in important factors in maintaining the viability of the banking sector. Furthermore, the

capital to asset ratio of banks remained constant around 11% during the crisis, showing the

soundness of Czech banks.

During 2010, the economy started rebounding slowly, yet high energy prices and low demand for

exports were drags on growth. The fall in economic activity significantly impacted corporations

whose default rates increased, leadings to cuts in production and increases in unemployment.

Following a contraction of 8% in 2009, loans to non-financial corporations were stable, while

loans for households increased at 7,5%, showing a slow-down from previous year level of 12%

(CNB 2011).

After decreasing the policy rate to 0,75% in May 2010, the CNB kept the rate stable until J une

2012 in an effort to boost the economic recovery. Nevertheless, the recovery lost steam during

2011, as net export and changes in inventory were the only drivers of growth. Due to low

domestic demand, firms which focus on internal market such as construction, real estate and

services posted disappointing results. Furthermore, low wage growth and high unemployment

were a drag on consumption and led to only a moderate increase in lending to households. On the

other hand, non-performing loans stabilized around 7% and the banking sector maintained a solid

capitalization ratio, showing signs that the worst had passed for the financial sector(CNB 2012).

13

Slow growth in EU started to impact exporting companies, which had been shielded from the

impact of the crisis, thus the Czech Republic fell into a recession again at the beginning of

2012.The economy continued to experience negative economic growth until the third quarter of

2013, mainly due to fiscal consolidation efforts and falling investment of firms. As a result, the

policy rate was decreased thrice in 2012 to 0,05%. Furthermore, the CNB announced it will

intervene in foreign exchange markets in order to keep the koruna close to CZK 27/EUR level in

order to prevent appreciation and support exports. Fortunately, external demand and household

consumption picked upin first quarter of 2014, pushing GDP growth to 2,5% (CNB 2013).

4.a) Money market rates

First of all, the pass-through from the policy rate to money market rates will be analyzed.

Interbank rates are obtained as monthly averages from the website of the Czech National Bank,

focusing on the main maturities: overnight, 1 month, 3 months and 1 year. Czech money market

rates follow closely the policy rate for maturities below 1 year before the financial crisis. Given

that around 80% of the market is traded on short maturities overnight or 1 week, these rates are

most significant. Furthermore, due to the low liquidity of longer maturities, these interest rates

are much more sensitive to shifts in the market and are characterized by higher volatility. All

rates spike in October - November 2008 after the fall Lehman Brothers, showing the large

amount of market unrest at the period. Accordingly, the Czech National Bank expanded its repo

maturity to 3 months and implemented a full allotment policy (CNB 2008). As can be seen from

the graph below, there was a spike in volumes for repo operations, helping money market rates

fall back to normal levels.Gersl and Lesanovska (2013) analyze the increase in the spread of

PRIBOR 3M from policy rate during the financial crisis and find that high counterparty non-

performing loan, as well as low bond market liquidity and volatility in EURIBOR money market

are the main determinants for the higher spread. Following November 2008, overnight rate

followed closely the policy rate, while the spread between maturities above 1 week narrowed

-8,0

-6,0

-4,0

-2,0

0,0

2,0

4,0

6,0

8,0

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Quarterly GDP growth

Euro area (12 countries) Czech Republic Germany

14

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

10 year bond yields

Czech Republic Germany Hungary Poland

significantly until February 2009. Nevertheless, given the extremely low volumes at higher

maturities (around 1% for maturities above 1month for 2008 and 5% for 2009 and 2010), these

developments are not particularly significant for the market(CNB 2012). Money market rates

continued to decrease with the policy rate, stabilizing in May 2010 as the Central Bank set the

policy rate at 0,75% and falling again in 2012 after the last round of policy rate cuts. They have

since remained at levels between 0.15% for overnight to 0.55% for 1 year maturity.

4.b) Government bond yields

Additionally, the pass-through from the policy rate to government bond yields will be measured

in order to see how debt instruments with longer maturities are impacted. Government bond

yield data is obtained from Czech National Bank and Bratislava Stock Exchange and is based on

a basket of government bonds with an average residual maturity for 2 years, 5 years and 10 year.

The average maturity of Czech government bonds has varied around 6,5 years since 2006, with

around half of outstanding debt above 5 years. Government bond yields moved with the policy

rate between 2004 and 2008, with the spread between 2 and 5 year maturities tightening as

policy rate increased. Bond yields spiked in J une 2008 and again in March 2009 for 2 and 5

years maturities and in J une 2009 for 10 years maturity.

0

10.000

20.000

30.000

0

1

2

3

4

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Money market rates

Liquidity providing repo (rhs) 1 day (%)

1 month (%) 3 months (%)

1 year (%) Policy rate

15

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Government bond yields

Bank holdings of government debt (rhs) 2 years maturity

5 years maturity 10 years maturity

Policy rate

Claeys and Vaek (2012) show that 50% of variance of Czech bond yields over German bonds

can be explained by external developments ofbond markets, with Hungary and Poland having

the largest impact. As 30% of government debt is held by investors, external perceptions on the

credit worthiness of Czech Republic as well as risk aversion in the markets may move yields

beyond their fundamentals during periods of unrest. This can also have a positive impact on

yields. For example, a dip in yields can be observed for all maturities at the end of 2001 as the

European Central Bank introduced Long Term Refinancing Operations. Overall, Czech bonds

are now seen by international investor as a safe asset offering an attractive yield, given the low

debt to GDP ratio of the Czech Republic (46% in 2014). This was also reflected by the Standard

and Poor decision to upgrade Czech government debt by two notches from A to AA- (Reuters

2011)

Furthermore, due to the high deposit to credit ratio of commercial banks and slow growth of

lending, Czech banks have increased their government bond yields holdings since the onset of

the crisis, driving down yields. Regulatory measures have also supported domestic banks holding

domestic bonds as they do not have to keep additional capital and can be used as collateral for

CNB repo operation, therefore they can be used as a liquidity buffer in times of unrest. (CNB

2012). Overall, Czech bond yields have been responsive to the decrease in the policy rate, falling

along with its changes and maintaining a constant spread of around 1% between maturities.

4.c) Household deposits

I will also analyze the price behavior of interest for deposits, both for households and non-

financial corporations. At April 2014, the majority of funds were held in overnight and current

accounts, reflecting a need for liquidity and a low incentive to save. Households split their

remainder of their funds between agreed maturity deposits and redeemable at notice accounts.

Nevertheless, the situation was quite different in 2004, when funds for households were split

evenly between overnight and agreed maturity deposits. While agreed maturity and redeemable

notice deposits remained stable, all growth in households funds went to overnight deposits.

16

0

200.000

400.000

600.000

800.000

1.000.000

1.200.000

1.400.000

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Household outstanding amounts

Overnight With agreed maturity total Redeemable at notice total

Furthermore, at the end of 2008 as market tensions began to rise, households shifted from agreed

maturity deposits to redeemable at notice due to higher uncertainty regarding the future and need

for easy access to liquidity.

In order to facilitate an easy understanding of the data, deposits for agreed maturity will be split

between interest rate fixation period shorter than 1 year and longer than 1 year. The interest rate

above 1 year will be constructed by using the weighted average of new amounts with maturities

above 1 year. Until 2009 interest rates above 1 year show very high volatility, while broadly

following the movement of the policy rate with a large delay until mid 2010. On the other hand,

deposits below 1 year followed closely movements of policy rate, maintaining a constant spread

of around 0,75% between 2004-2009. As the policy rate started decreasing, the spread became

close to zero as rates fell in sync. Since May 2010 when the policy rate stabilized at 0,75%, both

rates in household deposits have been driven mainly by competition from small banks and

building societies which offer higher rates than large and medium banks (on average 1,5%

higher, CNB 2011-2012), therefore interest rates of new amounts have shown a large degree of

volatility and a high spread above the policy rate.

17

Regarding deposits redeemable at notice, their rates show very low responsiveness to the

policy rate, therefore a very low pass-through is expected. The rates over 3 months have

fluctuated around 1%, while rates for maturities up to 3 months show a similar pattern around the

2% level.

4.d) Non-financial corporations deposits

For non-financial corporations, a detailed breakdown is not available between maturities,

therefore only the three main categories will be considered: overnight, agreed maturity deposits

and redeemable at notice deposits. Regarding outstanding amounts, deposits redeemable at

notice have a very small share for the entire period, while overnight and agreed maturity deposits

amounts are almost equal at the beginning of 2004. While agreed maturity deposits remained

relatively stable until the end of 2008, overnight deposits increased by around 40 bio CZK (1.8

0

1

2

3

4

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Agreed maturity -Households

Up to 1 year maturity Over 1 year maturity Policy rate

0

1

2

3

4

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Redeemable at notice & Overnight -Households

Policy rate Up to 3 months - HH Over 3 months - HH Overnight

18

bio EUR). Due to market tensions and decreasing interest rates, outstanding amounts for agreed

maturity deposits started falling at the end of 2008, leading to an increase of 60% for overnight

accounts increased between 2009 and 2014.

Regarding interest rates, overnight deposits are least responsive, fluctuating around 0,5%

until beginning of 2006. Afterwards rates started rising to a maximum of 1,2% in J une 2008,

falling again to an equilibrium level of 0,5% in March 2009. Deposits redeemable at notice

follow changes in the policy rate with a delay of around 3 months. The interest rate on

redeemable deposits switched from having a spread of around 1% below the policy rate to

having a positive spread which increased up to 1,9% in the beginning of 2013, four months after

the Central Bank lowered to its historical low of 0,05%. The spread has since fallen and seems

to have stabilized at around 1%, which is comparable to interest rates offered in the household

sector for redeemable deposits above 3months. Interest rates for deposits with an agreed maturity

show a much smaller spread to the policy compared to household agreed maturity deposits,

therefore showing a higher degree of competition for funds in the corporate sector and a higher

elasticity of demand given the larger number of alternatives available to corporates. Once the

Czech National Bank started implementing a looser monetary policy in August 2008, the spread

between agreed maturity interest rate and policy rate became even smaller, close to 0%, until

finally in June 2012 when the policy rate was lowered to 0,5% the spread became positive as

rates on agreed maturity deposits could not be lower than those offered for overnight deposits.

0

100.000

200.000

300.000

400.000

500.000

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Outstanding amounts -Non financial corporations

Overnight Agreed maturity Redeemable at notice

19

4.e) Household loans

Household loans are divided into three main categories: loans for house purchase, consumer

credit and other loans. Mortgages represent the largest share of outstanding loans given their

good quality of collateral and high ticket per loan. Given the low debt level of Czech households

at the beginning of the 2000s, (30% of GDP in 2004), there was a lot of potential for expanding

private lending. Therefore in the period preceding the crisis, mortgages increased by 35%

annually, while consumer credit and other loans grew at around 25%. As the financial crisis hit

Czech Republic, growth loans to households started slowing down, with mortgages stabilizing at

around 6% growth in early 2011, while consumer credit stopped growing in September 2009.

Overall, loan growth has been supported almost exclusively by mortgages over the past four

years, showing that banks are less willing to lend out money to households for loans with no

purpose attached or without collateral, as the increase in unemployment and stagnation in wages

have affected the credit-worthiness of households.

Share of household loans

Consumer credit

Lending for

house purchase

Other

31.1.2004 22% 67% 11%

30.4.2014 16% 73% 11%

0

1

2

3

4

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Non-financial corporations -deposits

Overnight Agreed maturity Redeemable at notice

Policy rate Agreed maturity households

20

Keeping in line with methodology used for deposit rates, loans will be separated depending on

their interest rate fixation period: below 1 year and above 1 year. The interest rates for interest

rate fixation period above 1 year will be constructed using weighted average of interest based on

new amounts.

Mortgages with higher interest rate fixation periods adjust slower to changes in the policy rate

and only partially. If the policy rate is decreasing, floating mortgages are preferable as they are

more susceptible to changes in the policy rate. Given the fact that rates have stayed low for such

a long period, longer maturities (1-5 years) have also been impacted, therefore it is profitable for

households to lock in these low rates for an extended period of time.

On the other hand, consumer credit and credit cards show very low responsiveness to changes in

the policy rate, given their high risk premium and poor collateralization. Credit card interest rates

-5%

5%

15%

25%

35%

45%

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Growth rate -Household loans

Total loans Consumer credit Lending for house purchase Other

0

10.000

20.000

30.000

0

2

4

6

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Mortages -Households

Over 1 year rate IRF - new amounts Floating rate and up to 1 year IRF - new amounts

Over 1 year IRF Floating and up to 1 year IRF

Policy rate

21

fluctuate around 20%, with the exception of 2009 when rates peak at 24%, afterwards returning

to the previous level. Consumer credit with an IRF above 1 year falls from 2004 to August 2006

to a low of 12%, afterwards fluctuating with no clear trend up to 15%. Overdrafts have a very

similar evolution to fixed rate credit card interest rates, showing no distinct trend over the

analyzed period. Floating interest rates for consumer credit show the highest volatility out of the

three series, having a delayed response to changes in the policy rate of around 14 months.

Nevertheless, they have decreased by 5% from their peak, showing some responsiveness to the

fall in the policy rate since 2008.

Between 2004 and 2006, the majority of new loans (80%) were floating rates as these had the

lowest rates. In the period following, until 2006, loans were split with around a third of new

amounts having floating rates, while the remainder had interest rate fixation periods above 1

year. Even though floating rates have been lower than fixed rates since 2012, most of the growth

in new loans has occurred in loans with fixed interest rates

4.f) Non-financial corporations loans

For loans above 30 mio CZK, no division is available based on interest rate fixation period,

therefore only total amounts will be analyzed. For loans below 30 mio CZK, , loans will be

divided depending on their interest rate fixation periods. Out of the interest rate analyzed so far,

loans for non-financial corporations have the highest responsiveness to changes in the policy

rate. Nevertheless, since August 2008 the spread against the policy rate has increased as the

default rate of companies started increasing, therefore banks became more risk adverse and

charged a higher risk premium. Loans over 30 mio CZK have a lower interest rate than loans up

to 30 mio CZK as larger firms have a lower probability of default and they have access to

alternative sources of finances, therefore they exhibit a higher elasticity of demand.

0

1

2

3

4

5

10

15

20

25

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Consumer credit, overdrafts and credit cards

Consumer credit - Floating rate and up to 1 year IRF Consumer credit - Over 1 year IRF

Overdrafts - HH Credit cards

Policy rate (rhs)

22

5. Results

As expected, interest rates are I(1), therefore looking at a cointegration relationship is

feasible as all rates have the same degree of integration.

5.a) Money market rates

Looking at the entire period, the long run pass-through is not significant, while it becomes

complete for sub-periods between 2008-2012. During 2004 the Czech National increased the

policy rate twice and decreased twice during 2005, therefore rolling estimates up to 2009show an

insignificant pass-through. Nevertheless, the pass-through steadily improved, becoming

complete by the end of 2011 and decreasing afterwards to 70% as policy rate approached the

zero lower bound.

The 1 month money market rate shows a lower degree of volatility, dipping from 90% before the

crisis to 60% at the end of 2008. Afterwards it stabilizes around 100% and, following a peak at

the beginning of 2013, it falls to 75%.

0

25.000

50.000

75.000

0

2

4

6

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Non-financial corporations loans

Loans over 30 mio CZK - new amounts (rhs) Loans up to 30 mio CZK - new amounts (rhs)

Over 30 mio CZK - total Loans up to 30 mio CZK -Floating rate and up to 1 year IRF

Loans up to 30 mio CZK - Over 1 year IRF Policy rate

23

The 3 month and the 1 year money market rates show very similar evolution to the 1 month pass-

through. They exhibit a drop in the pass-through to 60% during the unrest of 2008 and after J une

2012 as policy rate is approaching zero lower bound, but for the rest of the analyzed period the

pass-through is complete for 3 month rates and at 80% for 1 year rates. These results are in line

with gert, Crespo-Cuaresma et al. (2007)who find a complete pass-through from policy rate to

short term money market rates (1month) and long term (12 months) for the Czech Republic

between 1995 and 2005.

To conclude, money market rates have been weakened by the financial crisis between 20% and

40%, thus overnight and 1 month maturities now have a comparable pass-through around 70-

75%, while 3 month and 1 year maturities have stabilized around 60%.

5.b) Government bonds

Government bond yields with a 2 year maturity have a pass-through of 90% at the beginning of

the analysis, but this falls to 60% as the policy rate decreases between 2009-2013. Government

-1,5

-1

-0,5

0

0,5

1

1,5

2004-

2008

2005-

2009

2006-

2010

2007-

2011

2008-

2012

2009-

2013

2010-

2014

Overnight -ECM

0

0,5

1

1,5

2004-

2008

2005-

2009

2006-

2010

2007-

2011

2008-

2012

2009-

2013

2010-

2014

1 month -ARDL

0

0,2

0,4

0,6

0,8

1

1,2

1,4

2004-

2008

2005-

2009

2006-

2010

2007-

2011

2008-

2012

2009-

2013

2010-

2014

1 year -ARDL

0

0,2

0,4

0,6

0,8

1

1,2

1,4

2004-

2008

2005-

2009

2006-

2010

2007-

2011

2008-

2012

2009-

2013

2010-

2014

3 months -ARDL

24

bond yields with a 5 year maturity have a pass-through of 50% at the beginning of the period,

climbing up to 70% at the end of 2008, but becoming insignificant afterwards.

The regression is significant only for the period before the crisis, with a coefficient of 65%. This

can also be observed from the graph of the long run coefficient which becomes insignificant

from the end of 2008.

Singh, Razi et al. (2008) show that the pass-through to 3 month T-bill rates in developed

countries

4

is close to 1 in the long run, while long term bonds with maturities between 3 and 5

years have a long run pass-through between 65% (Germany) and 81% (US). Therefore results for

Czech Republic before the crisis are in line with pass-through in developed countries.

Government bonds with higher maturities are less responsive to changes in the policy rate and

have been affected to larger extent by the financial crisis. Furthermore, as the policy rate

approached the zero lower bound, the pass-through becomes insignificant for all maturities as

4

The countries analyzed are :UK, Australia, Canada, the US and Germany

-2

-1,5

-1

-0,5

0

0,5

1

1,5

2

2004-

2008

2005-

2009

2006-

2010

2007-

2011

2008-

2012

2009-

2013

2010-

2014

10 year maturity -ARDL

-1

-0,5

0

0,5

1

1,5

2

2004-

2008

2005-

2009

2006-

2010

2007-

2011

2008-

2012

2009-

2013

2010-

2014

2 year maturity - ARDL

-1,00

-0,50

0,00

0,50

1,00

1,50

2,00

2004-

2008

2005-

2009

2006-

2010

2007-

2011

2008-

2012

2009-

2013

2010-

2014

5 year maturity - ARDL

25

government bond yields are driven by other factors beyond the policy rate. Therefore the impact

of the crisis on the long run pass-through has been much more pronounced regarding government

bonds as opposed to money market rates.

5.c) Household deposits

Up to 2009, the pass-through for overnight deposits shows very large standard errors, but is still

significant. Nevertheless, from 2009 the long run impact is stable and significant throughout the

entire period with a coefficient of 18%. The immediate impact is only significant in the period

previous to the crisis, as well as the adjustment speed, showing a slowdown in the transmission

of policy rate to overnight rates. The pass-through weakens again from 2013 when the last round

of policy cuts was instituted by the Czech Central Bank, as rates for overnight deposits remained

stable despite the lower policy rate.

When regressing the overnight rate to the 2 year government bond yield, the long run coefficient

is significant only for the full period at 7%, but loses significance when analyzing the sub-

periods or running the rolling regression. Therefore the monetary approach is more suited for the

estimation of the pass-through.

Deposits with maturity less that 1 year are more responsive to changes in the policy rate, having

a long run pass-through of around 80%-85% up to the end of 2012, with the exception of a drop

at the end of 2008 which was due to market unrest. The long run coefficient becomes

insignificant from April 2013. The adjustment speed is 0,35 before crisis, showing that the

impact of the policy change in fully implemented in 3 months, but it becomes insignificant after

the crisis. Implementing the cost of funds approach, the pass-through from 3 month money

market rate is slightly higher (71% vs 66% for the entire period), but given their standard errors,

the results are not significantly different. Therefore the cost of funds approach yields consistent

results with the monetary approach.

On the other hand, deposits with maturities above 1 year are not impacted at all by changes in the

policy rate throughout the analyzed period, with short run, long run and adjustment speeds being

-0,4

-0,2

0,0

0,2

0,4

0,6

0,8

2004-

2008

2005-

2009

2006-

2010

2007-

2011

2008-

2012

2009-

2013

2010-

2014

Overnight deposit -ECM

26

insignificant. The pass-through from the 10 year government bond yields is also not significant,

showing that deposits rates are not related to longer maturities either.

Given the very low volumes of deposits with higher maturities, the interest rate is quite sensitive

to changes in new amounts, therefore a high degree of volatility and low responsiveness is

expected. Furthermore, as banks seek long maturities in the context of uncertainty in market,

they are willing to pay a high premium above the policy rate in order to secure long term

funding, therefore changes in the policy rate are not reflected in these rates.

Even though the long run pass-through is significant for maturities up to 3 months from the

beginning of 2009, the long run impact is quite low at around 8%. As was seen with deposits

with agreed maturities, the coefficient ceases to become significant after 2013 as the policy rate

reached the zero lower bound. When employing the cost of funds method, the pass-through from

2 year government bond yields is not significant, therefore the monetary policy approach is

preferred for measuring the pass-through.

For deposits redeemable at notice with maturities above 3 months, the long run coefficient of

around 25% period preceding the crisis. Afterwards it decreases quite abruptly becoming

insignificant by the end of 2008. Since 2013, the long run pass-through has been improving as

rates fell slightly as the policy rate was decreased. The cost of funds approach yields an 11%

pass-through from 5 year government bond yield, showing that the policy rate has a larger

influence on deposit rates.

-1,5

-1

-0,5

0

0,5

1

1,5

2

2004-

2008

2005-

2009

2006-

2010

2007-

2011

2008-

2012

2009-

2013

2010-

2014

Agreed maturity over 1 year - ARDL

-1,5

-1,0

-0,5

0,0

0,5

1,0

1,5

2004-

2008

2005-

2009

2006-

2010

2007-

2011

2008-

2012

2009-

2013

2010-

2014

Agreed maturity -less than 1 year - ARDL

27

Deposits with short maturities such overnight and redeemable at notice have a low

responsiveness to changes in the policy rate. Preceding the crisis, deposits with agreed maturity

with maturities below 1 year had an almost complete pass-through, while those with maturities

above 1 year have an insignificant pass-through. Overall, the pass-through weakened during the

turmoil of 2008 and has become insignificant from the end of 2012 as the policy rate approached

the zero lower bound. Deposits redeemable above 3 months are the only exception, showing

improvement since 2013, yet they represent only a small fraction of funds held by population.

Lastly, the monetary approach seems better suited to describe the pass-through as deposit rates

show a higher responsiveness to changes in the policy rate as opposed to other money market

rates or government bond yields

5.d) Non-financial corporations deposits

The long run pass-through for overnight deposits is significant and stable at 29% for the entire

period. The adjustment speed is 0,25 for the entire period, increasing to 0,75 when analyzing the

period before the crisis showing a faster transmission from policy rate to overnight deposits.

Analyzing the rolling regression graph, the long run coefficient is stable at around 35% since

2009, but falls to 0% the end of 2012 as rates remained at the 0,25% level while the policy rate

fell to 0,05%. The long run pass-through measuredwith the cost of funds shows a similar

evolution as the market rate chosen in overnight which has a high correlation with the policy

rate.

-0,4

-0,3

-0,2

-0,1

0

0,1

0,2

0,3

0,4

2004-

2008

2005-

2009

2006-

2010

2007-

2011

2008-

2012

2009-

2013

2010-

2014

Redeemable at notice -less 3

months -ARDL

-0,4

-0,2

0,0

0,2

0,4

0,6

0,8

1,0

2004-

2008

2005-

2009

2006-

2010

2007-

2011

2008-

2012

2009-

2013

2010-

2014

Redeemable at notice over 3

months -ARDL

28

Unlike other rates, agreed maturity depositsshow a lower pass-through before the crisis as

compared to the period after the crisis. The pass-through steadily improves from 80% at the

beginning of 2008, stabilizing at 100% since mid-2011. The pass-through falls at the beginning

of 2013 to 60% as the policy rate stabilizesatthe 0,05% level. Furthermore, the adjustment speed

also improves in the period following the crisis with a coefficient of 0,7, compared to 0,5 for the

entire period.As in the case of overnight deposits, the results from the cost of funds approach are

very similar as the chosen money market rate is overnight one.

The long run pass-through for deposits redeemable at notice starts out at around 60% for period

between January 2004 August 2008, but falls sharply until J anuary 2009 to a minimum of

10%.For the next four years it stabilizes around 30%, decreasing again to levels shown during

the crisis from the end of 2013.The cost of funds approach measures the pass-through from the 2

year government bond yield, showing a much weaker pass-through.

-0,1

0

0,1

0,2

0,3

0,4

0,5

0,6

2004-

2008

2005-

2009

2006-

2010

2007-

2011

2008-

2012

2009-

2013

2010-

2014

Overnight -ECM

0

0,2

0,4

0,6

0,8

1

1,2

2004-

2008

2005-

2009

2006-

2010

2007-

2011

2008-

2012

2009-

2013

2010-

2014

Agreed maturity -ECM

29

Comparing to household deposits, the pass-through for overnight and deposits redeemable at

notice is higher by 10%-30% for the entire analyzed period. On the other hand, deposits with

agreed maturity have similar pass-through preceding the crisis, but are much more resilient since.

Unlike household deposits that have become insignificant, agreed maturity deposits for

corporations still have a 60% pass-though.

5.e) Household loans

Floating mortgages have long run pass-through of 75%, yet very high standard errors. From

analysis of rolling regression output, it is observable that the long run coefficient quickly

becomes insignificant and remains so until the end of the analyzed period. The situation is quite

similar for mortgages above 1 year, starting out with a pass-through of 70% but becoming

insignificant by the end of 2008.Given that mortgages with interest rate fixation above 1 year

make up 50% of overall new loans, the disruption of the pass-through from policy rate to

mortgage rates is quite worrying in assesing the impact of the central bank on real economy.

The cost of funds approach calculates the pass-through from 10 year government bond yeilds to

mortgages and shows much weaker results. Despite their long maturities, mortgages are priced

more in accordance to development of the policy rate, rather than instrumetns with longer

maturities.

-0,6

-0,4

-0,2

0,0

0,2

0,4

0,6

0,8

1,0

2004-

2008

2005-

2009

2006-

2010

2007-

2011

2008-

2012

2009-

2013

2010-

2014

Redeemable at notice -ARDL

30

The pass-through for consumer credit loans is insignificant for both short run and long run

impact. This is expected as these types of loans have a very high unit costs, low elasticity of

substituion with other financial goods and a high credit risk. Therefore banks price such loans

with a high margin above policy rate.

Credit cards and overdrafts are in a similar situation as they have high unit price per ticket, poor

collateral and high credit risk. Therefore results not significant for either of the sub-periods

analyzed. When calculating the pass-through using the cost of funds methodology, consumer

credit loans, credit cards and overdrafts have the highest correlation with 10 year government

bond yields but still have an insignificant pass-through.

-2,5

-1,5

-0,5

0,5

1,5

2004-

2008

2005-

2009

2006-

2010

2007-

2011

2008-

2012

2009-

2013

2010-

2014

Mortgage less 1 year -ECM

-0,4

-0,2

0,0

0,2

0,4

0,6

0,8

1,0

2004-

2008

2005-

2009

2006-

2010

2007-

2011

2008-

2012

2009-

2013

2010-

2014

Mortgages over 1 year -ARDL

-3

-2

-1

0

1

2

2004-

2008

2005-

2009

2006-

2010

2007-

2011

2008-

2012

2009-

2013

2010-

2014

Consumer credit less 1 year - ARDL

-2

-1

0

1

2

2004-

2008

2005-

2009

2006-

2010

2007-

2011

2008-

2012

2009-

2013

2010-

2014

Consumer credit over 1 year - ARDL

31

5.f) Non-financial corporations loans

Before the crisis, loans below 30 mio CZK exhibited a full pass-through with a long run

coefficient of 106%. Looking at the two different interest rate fixation periods, floating rates are

much more responsive to changes in the policy rate and the pass-through becomes insignificant

only at the end of 2011. On the other hand, loans with interest rate fixation period start out with a

lower long run pass-through (85% vs 95% for floating rates) and decreases much faster,

becoming insignificant from the beginning of 2009.

While in the period preceding the crisis, loans over 30 mio CZK had a lower pass-through (86%)

compared to loans up to 30 mio CZK (106%), these loans have maintained a substantial pass-

through from the beginning of the crisis. The pass-through weakened by 30% starting in 2009,