Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Manual Torno

Загружено:

julie242014Исходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Manual Torno

Загружено:

julie242014Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

LeBlond Regal Lathes

Operation, Maintenance & Parts Manuals are available for all the Regal lathes.

Email for details

A very successful manufacturer, the R. K. LeBlond Machine Tool Company of Cincinnati, Ohio had, since

its founding in 1888, outlived five production plants, with each in turn being replaced by a bigger and

better-equipped facility. By 1929 their 440,000 square-foot factory, set in pleasant grounds at the corner of

Madison and Edwards Roads, Hyde Park, was employing some 900 people all devoted exclusively to the

manufacture of heavy industrial lathes from ordinary "engine" types (backgeared and screwcutting to the

UK reader) to massive 60,000 pounds crankshaft-turning models equipped to finish all eight crankpins on

an eight-cylinder engine at the rate of twenty cranks per hour. Whilst that might be considered a modest

achievement set against 21st century machining times it was, for the era, a significant technical

achievement and enabled LeBlond to offer state-of-the-art manufacturing equipment to automobile and

other mass-production makers. Unfortunately, in 1930, LeBlond faced, as did all manufacturing industry,

the Great Depression and its accompanying slump in trade. In order to survive the company decided to

widen its market and introduced, alongside it's long-established range of heavy engine lathes, a range of

lighter, more-affordable models designed to appeal to the lower end of the market: better-off home-

experimenters and model-makers, research departments, training schools, motor-repair garages, the self-

employed and similar buyers. However, even with keen pricing and the backing of the respected LeBlond

name, success could not be guaranteed for the new range, branded "Regal", entered a section of the

industry already dominated by, amongst others, such well-established makers as South Bend, Sheldon,

Barnes and Seneca Falls. Thankfully for the shareholders, LeBlond's approach was well thought out:

although the lathes would only weight from one-third to one half as much, they would all mirror the

quality and desirability of their industrial equivalents. They would have the most up-to-date specification

possible, be easy to operate, come equipped ready for use and be introduced as a complete range with 10,

12, 14, 16 and 18-inch swings (actual capacity was always slightly more) Headstocks would be all-geared

(no alternative flat or V-belt drive versions would be offered) with lever-operated speed changes and the

exclusive use of built-on, self-contained motor drives with power transmitted to the headstock input shaft

by the use of the recently-introduced (circa 1930) V-belt. All would have a proper screwcutting gearbox, a

separate feed-rod to drive the sliding and surfacing feeds (engaged by a fool-proof, snap-engagement

system) and a robust carriage assembly whose design was not compromised by having to allow for a gap

bed. As the sole concession to hard times the cheapest model, the 10-inch, could be had to special order

without the power cross feed and with a set of changewheels for screwcutting. Popular in the UK during

WW2 (and with many examples still in use in the 21st century) production of the 10-inch was to end in

1945 - though other models, constantly developed and refined, continued into the 1980s. Notable changes

in design occurred in approximately 1946 and (in very much more radial form) during the late 1950s when

an even wider variety of models and types was introduced. The two earlier types are easily distinguished

by the disposition of their headstock controls and the final model (in standard, Servo-shift and sliding-bed

forms) by its modern, very angular lines. Although the larger Regal lathes in 21 and 24-inch sizes were

enormous machines, comparable in some respects to the proper very heavy-duty LeBlond engine lathes,

unfortunately there was an attempt to stretch them beyond their limits with the introduction of what

amounted to very large-bore "Oil Country" headstocks.

In the 1980s LeBlond had tried to produce their lathes, particularly the lighter "Regal" models, all (or in

part) at a low-cost plant in Singapore. This was the last gasp for the company and, when the new Japanese

owners, Makino, had finished with them, they had built their last proper engine lathes. Unfortunately the

patterns, core boxes, jigs and fixtures had all been shipped to Singapore and, when the end came, all were

ordered to be burned or scrapped - a decision that precluded anyone from trying to resurrect the machines.

Continued below:

LeBlond Regal 10-inch

Continued:

Early Models

Made from close-grained iron mixed with steel and nickel the bed carried inverted

"V" and flat ways (separate for carriage and tailstock) with the front and back walls

in the form of I beam sections joined by closely-spaced cross girths. The beds were

first rough machined and then seasoned for some months before being finished

planed in batches and then hand scraped to a "master". Each saddle assembly was

also scraped to its particular bed and then, with the apron fitted, the carriage rack

located to the bed with screws and dowel pins. An enormous variety of bed lengths

was available that gave between-centres' capacities of 18", 24", 30", 36" and 42" for

the 10-inch, 12-inch and 14-inch models (with an additional 66-inch model for the

12-inch and 14-inch swing lathes only) whilst the 16-inch and 18-inch could be had

with a capacity of 30", 42", 54", 78" and 102" - and 126" for the 18-inch model only.

On all sizes of "Regal" the headstock was of similar construction with a box-form

casting, closed at the top (with a heavy iron cover), reinforced under the main

spindle bearings and with an oil bath in the base to lubricate the gears by splash.

LeBlond recommended: "a medium grade of machine or automobile oil" - though

this would have been before the addition to motor oils of chemicals unfriendly to

machine-tool components left standing unused for long periods. The spindle

bearings, phosphor bronze but tinned with a layer of high-quality "babbit", were

retained by heavy caps locked down by Allen-headed socket screws. The bearings

were hand scraped to the spindle and (to keep out any particles from worn gears)

lubricated from separate flip-top oilers fitted with felt filter pads. Although the very

powerful LeBlond industrial engine lathes would have had their main headstock

gears made from drop forgings, on the Regal line all were made instead from steel

blanks. After the machining the bore, keyways, splines, sides and cutting of the

teeth, each gear was burnished before being subjected to a hardening heat treatment

process. Other than those on the main spindle, headstock gears ran on shafts

spinning in plain phosphor bronze bearings fed with splash oil that had been

collected in reservoirs and filtered through felt pads. The final drive gears were of

helical form and provided not only an exceptionally quiet and smooth-running

headstock when new but also when well worn and badly abused. 8 spindle speeds

were provided with a high/low lever on the right of the headstock's front face and a

four-speed selector to the left with both indexing through positions located by

spring-loaded plungers. To aid speed changes (and engagement of tumble reverse) a

polished-rim handwheel was formed as part of the headstock drive pulley and

arranged to protrude through the cast-iron belt-run cover. By gently moving the

wheel back and forth the operator was able to persuade the gears into mesh as he

moved the headstock selector levers. Although rather small on early versions the

wheel was later increased in size to almost the full diameter of the pulley.

On stand-mounted lathes the hinged motor-plate (adjustable for belt tension) was

bolted to the back of the headstock-end leg and on bench machines to the rear of an

extended headstock-end foot. Although underdrive systems with the motor inside a

cabinet leg had been in production for some time the importance of this new system,

with its deceptive neatness, simplicity and economy cannot be understated for it

quickly became an industry standard, being copied by almost all other makers of

similar machines. A further important point was the provision as standard of an

electrical reversing switch, mounted in a convenient position on top of the

headstock: when the lathe was delivered it could be put to work straight away and its

position in the factory of workshop determined not by where a cumbersome

countershaft could be mounted, or the line-shafting picked up, but where was most

convenient and efficient.

Continued below:

Early Regal headstock with 2-lever control of spindle speeds

Continued:

In order to give maximum support to the cutting tool the saddle was fitted with four

long, equal-length wings and the cross-slide (unfortunately of the short type that

tended to wear just the front and middle part of its ways) arranged to sit on its exact

centre line. This theoretically desirable state of affairs was permitted by both setting

the front and back faces of the headstock inwards - and so allowing the saddle wings

to run on past the spindle nose - and the absence of an gap in the bed, an undeniably

useful feature but one that brings complications in its wake.

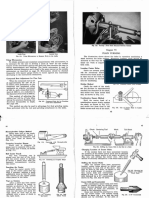

The apron of the 10", 12" and 14" models was of identical design and, although of

single-sided construction, was heavily built, tongued on the ends to locate to the

saddle, clamped by 4 bolts and incorporated proven features from the maker's larger

engine lathes. The gears were all cut from the solid and mounted on good-sized studs

that ran in long, wear resistant housings. To ensure as rigid an assembly as possible

the apron was dowelled to the saddle and clamped by a recent invention, socket-

headed Allen screws, whose clamping force was so much easier to exploit that the

slot-headed screws used by so many other makers that had to be tightened by

nothing more than a glorified screwdriver. The arrangements for power sliding and

surfacing feeds were well though out, of robust simplicity, and known for a long and

trouble-free life. A feed-rod, slotted to pick up a key carried inside a long sleeve held

in a bearing on the inside face of the apron, emerged from the screwcutting gearbox.

On the end of the sleeve was a small pinion that drove a large crown wheel on whose

supporting shaft was cut a wide-faced pinion. The drive was made to pass from the

wide pinion to either the cross-feed screw or the bed rack by means of a 3-position

sliding gear the knurled head of which emerged through the face of the apron as a

selector for the operator to manipulate. With the selector pushed in power sliding

was achieved (up and down the bed) with it pulled fully out power cross feed was

selected. Only in its middle position would it safely allow the leadscrew clasp nut to

be closed for screwcutting. Whilst the push-pull button selected the appropriate feed

direction for engagement and disengagement a separate lever with two spring-

indexed positions was used that simply slide the pinion into and out of engagement

with the crown wheel. Unlike the "safety" wind-in-and-out clutches used by some

makers that required the operator to anticipate the disengage position and then

unscrew a control knob to stop the feed on the LeBlond the action was instantaneous

and absolutely safe. To prevent damage to the gears by, for example, running the

carriage into the chuck, the feed-rod on the 10, 12 and 14-inch models was in two

parts but connected at a socket where a cross drilling on the inner shaft held a

powerful spring that pushed on a ball bearing at each end. The balls sat in shallow

sockets drilled in the outer shaft and, under normal conditions, the two parts rotated

as one. In the case of an overload the spring-loaded balls allowed the shafts to slip

but, as soon as the stress was removed, the mechanism automatically reconnected the

drive. On the 16 and 18-inch versions a simple shear pin was provided in the feed-

rod drive, the excuse advanced being that the more experienced craftsman employed

on such large lathes would be unlikely to make simple handling errors.

The apron of the larger Regal models was an exact duplicate of that used on the

company's heavy-duty engine lathes. Of double-wall construction, made from a

single casting and braced by cross ribs, LeBlond claimed that its patented design

contained around 50% fewer parts than generally used by competing manufacturers

and was thus far less likely to go wrong or suffer wear of small but critical

components. The main drive gears were made from drop-forged steel and ran on

hardened and ground shafts with the bed rack engagement gear (the rack pinion, a

source of weakness on many lathes) being in chrome nickel alloy steel normalised

and hardened. The same sort of large crown wheel was used but driven by either of

two pinions, one at each side and selected by a lever on the apron face, which had

the effect of causing the carriage to move left or right without having to reset the

headstock-mounted tumble-reverse mechanism. In the centre of the assembly was a

"spider clutch", a ring of fine teeth, used to engage and disengage the drive.

Although of different internal design the apron used external controls that mirrored

those on the smaller machines: there was a similar kind of in-out feed selector button

and one easily-operated lever (connected to the spider clutch) to instantly start and

stop the feeds - with no friction device to hamper the process.

Continued below:

Early Regal carriage assembly

Continued:

Of utterly conventional design the compound slide rest had (the usual failing at the

time) rather small friction micrometer dials, gib strips adjusted by pusher screws and

a "short" cross slide that tended to concentrate wear the front and middle part of its

ways. The top slide was clamped down by two T-bolts with their heads held in a

circular T-slot machined in the cross slide. The graduations to indicate the degree of

swivel were on the inside front edge, and hence difficult to read, but its tool-holding

T-slot was usefully-large.

On all sizes of the first Regal lathe the screwcutting arrangements were identical -

with an output gear on the spindle driving through an externally-mounted tumble-

reverse mechanism (a reverse plate in LeBlond terminology) with the gears in steel

and running on hardened studs. Whilst it was not unusual for smaller lathes to have

the tumble gears on overhung shafts (and continues so to this day) on larger

machines, from many makers, they were generally fitted inside the headstock where,

better supported and running in oil, they had a far easier time. After WW2 LeBlond

redesigned the Regal headstock so this improvement was included and also removed

the quadrant-arm mounted sliding gear (that provided a change between fine-feeds

and screwcutting) and built that mechanism into the headstock as well. The later,

improved headstocks are easily identifiable by a pair of small levers, set one above

the other between the main spindle speed-change levers.

Shared by the 10", 12" and 14" Models, the same ingeniously-designed quick-

change screwcutting and feeds gearbox was used and consisted of a separate unit

bolted to the front of the bed. The 20-degree pressure angle gears were all in steel

(though not hardened) and lubrication of the box depended upon the whim of the

operator who had to swing aside a protective plate on the top and use an oil can to

fill a small reservoir from which lubricant tricked down various holes to appropriate

places. An eight-position, spring-plunger selector slid along a long cylinder and

protruded from the face of the box. It carried a captive gear that was permanently

meshed with a long gear on the inside of the cylinder and could also be engaged with

any of eight feed gears on an intermediate shaft. A horizontal, three-position lever at

the bottom of the box and provided three different ratios for each of the eight

positions on the tumbler (giving twenty-four in total) whilst a two-position sliding

gear on the gear train from the headstock (its head protruding through the gear

guard) doubled the number of feeds and pitches to a total of forty-eight. Pitches

varied from 2 to 112 t.p.i and feeds from 0.0025" to 0.144" per revolution of the

spindle. Whilst the drip-lubricated screwcutting and feeds box used on the larger

models was of a similar appearance to that used on the smaller versions its internal

design was more akin to those employed on the company's larger commercial lathes,

a design so successful that the company was able to proudly claim that the number

of gearbox repair parts requested over 25 years been "practically nothing". A four-

position selector on the face of the box increased the total number of threads and

feeds to 56. Pitches varied from 1.5 to 184 t.p.i and longitudinal feeds from 0.001" to

0.125" per revolution of the spindle.

Unlike many machine-tool manufactures, including South Send, who bought their

leadscrews in from specialist makers LeBlond made their own from lengths of a

high-carbon steel bought in as ground stock. The left-hand Acme-form thread was

first roughed out on a thread milling machine and the leadscrew then rested for a

time sufficient to relieve the strains of the initial machining. It was then finished by a

"thread-chasing" process on a special lathe equipped with a precision leadscrew

itself cut from a certified Master Leadscrew kept under temperature controlled

conditions. The screw was mounted on the lathe between ground washers with the

thrust arranged to be taken at the better-supported gearbox end when cutting right-

hand threads. Like other parts of the various models the leadscrews were properly

sized according to their duties: 8 t.p.i by " diameter on the 10-inch model; 6 t.p.i.

by 1" on the 12-inch and 14-inch and 4 t.p.i. by 13/16" on the 16-inch and 18-inch

versions.

Continued below:

Apron as used on the first Regal 10, 12 and 14-inch models

Continued:

The tailstock was typical of LeBlond practice: hand-scraped to the bed and built so

that the upper section could be off-set on the sole plate for the turning of shallow

tapers, the casting was also carefully shaped so that when brought up along side the

top slide the latter could still be operated when turning very short jobs between

centres. The Morse-taper spindle was of high carbon steel, ground finished and

marked with ruler graduations for drilling. It was driven by an Acme thread running

though a bronze nut and locked by a substantial lever that closed down opposing

clamps.

The company's move into a new product line at the beginning of the 1930s proved to

be fully justified with the Regals remaining in production until the early 1960s when

they were replaced by a range carrying the same name but of radically altered design

and very angular, modern styling. Although during their long production run the

lathes remained essentially the same, after WW2 the 10-inch dropped and the other

models revised with 13", 15", 17", 19", 21" and 24" swings (an interesting machine

introduced at the same time, though it shared nothing with the Regal, was the

ingenious if complex Dual-Drive. During the 1940s a number of improvements were

made to functionality and durability by including the use of heavier stands with cast-

iron box plinths beneath headstock and tailstock and offering as extras, various

features including higher speed ranges to take advantage of carbide-tipped tools,

roller-bearing headstocks, gap beds, a one-shot lubrication system that oiled the

apron internals and bed and cross-slide ways, the useful feed-rod safety coupling

extended to the whole range (instead of just the smaller models) and headstock

spindles fitted with a multi-disc clutch and brake unit operated by duplicated

controls levers on apron and screwcutting gearbox.

Regal lathes were offered with the usual range of accessories - chucks, steadies,

taper-turning attachments, toolpost grinders, micrometer carriage stops - as well as

an unusual "Millerette" attachment. Built in three sizes the unit carried a T-slotted

table on which was mounted a worm-and-wheel driven indexing unit that allowed,

besides the usual milling operations, dividing work and the generation of spur and

bevel gears, splines and slots.

Tony Griffiths

Apron used on the early 10, 12 and 14-inch models

Apron used on the early 10, 12 and 14-inch models

Early 10, 12 and 14-inch screwcutting gearbox

Inside the early 10, 12 and 14-inch screwcutting gearbox

LeBlond Regal Lathes

Operation, Maintenance & Parts Manuals are available for all the Regal lathes.

LeBlond "Dual-Drive" Lathe Mk. 1

Introduced in 1946, the 15-inch swing by 30-inch between centres LeBlond "Dual Drive" was to be built in Mk. 1

and Mk. 2 versions in attempt to provide a versatile lathe for "training, maintenance, experimental workshops and

light production duties". The main feature of this heavy, 2450 lb lathe was a headstock of mechanical complexity

with two separate drive systems powered from a single, 1800 r.p.m 3 h.p. motor mounted on a pivoting plate

underneath the headstock. A quiet-running high-speed range (540, 782, 1140 and 1800 r.p.m.) was provided by 4

V-belts and low and intermediate speeds (28, 41, 60, 95, 134, 193, 282 and 445 r.p.m.) by a fully-geared drive

where greater torque was required for such tasks as turning large diameters or achieving higher-than-usual rates of

metal removal. The Dual-Drive was mounted as standard on separate heavy-gauge sheet-steel plinths under

headstock and tailstock with a chip tray incorporating a deep central swarf pan. Doors in both end faces of the stand

gave access to the motor compartment beneath the headstock and a storage compartment at the other end.

Continued below:

Mk. 1 LeBlond Regal Dual-drive

Continued:

Of typically LeBlond design, the headstock, was heavily built with hardened and ground alloy-

steel gears running on drive shafts that were all, with the exception of the bronze-bushed feed from

spindle to changewheels, supported in ball or roller bearings. The No. 4 Morse taper headstock

spindle was bored through 1.5-inches, ran in taper-roller bearings and - surprisingly in view of the

lathe's strength and capacity - was fitted with only the smallest of the American long-key taper-

nose fittings - an L00. Instead of a simple splash lubrication system the headstock was provided

with an automatic forced feed from a pump - though this worked only when the spindle was going

forwards; if used in reverse for any length of time the makers advised running forwards

occasionally to feed oil to gears and bearings or, if used continuously in reverse, to take out the

unidirectional pump and replace it at 90-degrees to its normal position. With great ingenuity the

designers had arranged not only for one control lever to select the 12 speeds (by rotation and

though a hinge that provided an axial movement) but also for the carriage feed rate to be slowed

automatically when a change was made from slow-speed gear to high-speed belt drive. Although

the 4-step V-belt drive pulleys on motor and input shaft were entirely conventional the final drive

(for the high-speed) was by twin V-belts running on pulleys a fixed distance apart with no means

of adjusting the belt tension. Because the makers must have rejected the idea of using "link-belts",

the lower pulley had to be made adjustable: this was achieved by producing a large hub with its

right-hand flange formed as the outer section of one V-pulley. Keyed to the hub, and adjustable

along it, was a central ring machined so that each side formed one half of a V groove; to complete

the assembly a second ring, again machined with half a V groove, was screwed to the outer part of

the hub. By adjusting the position of the central and outer rings (by means of a screw-on boss) the

effective width of the V-grooves could be narrowed or widened and hence the belts moved slightly

inwards or outwards to adjust the tension. On lathes with serial numbers 2 to 225 and 227 to 272

inclusive the drive to the spindle incorporated a combined multi-plate clutch and brake unit

mounted outboard of the 4-step headstock drive pulley whilst all the others should be found fitted

with a self-adjusting and maintenance free electrically-operated brake. The electrical control of the

spindle (start, stop, reverse and brake) was by a "third-rod" system with two control levers, one on

the screwcutting gearbox and the other on the right-hand face of the apron.

Continued below:

Continued:

After the complications of the drive system and headstock the rest of the lathe was refreshingly

straightforward, though, at the same time, well up to contemporary standards of design. The bed

was enormously strong, 11-inches wide and 9.75-inches deep and could be ordered in length

increments of 12-inches (though in catalogues the lathe appears only as a 30-inch between centres

model). Whilst on early versions the ways for the carriage were machined from the bed material,

and of conventional, symmetrical inverted V pattern, later machines used separate hardened steel

ways with that at the front in a form LeBlond termed "compensated" - that is, an extra-wide,

shallow-angle outer surface (to better absorb wear) and an inner surface set at a much steeper

inclination to take tool thrust. The ways, both ran on past the front and back faces of the headstock

so allowing the carriage to overlap it and permit the carriage to be of symmetrical design with long,

equal-length wings and the cross slide positioned exactly on its centre line. Formed from a one-

piece casting with double walls the apron held a supply of oil in its base distributed by a hand-

operated plunger pump to the apron bearings and gears, the cross slide ways and bed. The power

sliding and surfacing feeds were arranged in a manner similar to that employed on the larger of the

early Regal lathes with instant, easy and fool-proof selection and engagement no matter how heavy

the cut. A separate slotted power rod, driven by a multi-face dog clutch on the output from the

screwcutting gearbox and fitted with the usual LeBlond design of safety-overload, spring-loaded,

automatically re-setting ball-bearing clutch, ran through an apron-mounted pinion and drove it

through a sliding key. The pinion drove, in turn, a crown wheel and then (through a toothed "face

clutch" and a sliding selector gear controlled by a single handle on the face of the apron), the power

feeds. A separate lever, emerging from the apron's right-hand face, was used to clutch the feeds in

and out. Unlike the heavier LeBlond lathes the carriage feed could not be reversed from the apron

instead the usual headstock-mounted lever was employed working through an internally mounted

tumble-reverse mechanism. A useful device fitted to all Dual-Drives was a multiple automatic

length stop. This consisted of a long bar below the feed-rod supplied with three adjustable stops

(though more could be fitted) that engaged against an trip bar that stopped the carriage drive by

feed-rod's dog clutch. By just lifting the trip lever handle a spring snapped the bar to the right and

re-engage the feed-rod clutch.

Continued below:

Dual-drive headstock interior

Continued:

Fully enclosed, the screwcutting and feeds gearbox was provided with a positive flow of oil from

the same pumped supply used by the headstock. The initial 2-speed drive to the box was from a

lever on the headstock marked fine and coarse feeds. An 8-position spring-loaded tumbler then

selected the main pitches with each having three ratios selectable by a 3-position quadrant lever on

the face of the box - thus giving a total of 48 pitches and feeds. The leadscrew was normally left

disengaged other than when screwcutting with a 2-position lever, on the face of the box, providing

easy selection and disengagement.

With good-sized zeroing micrometer dials the compound slide rest had taper gib strips adjusted by

pusher screws at front and back. The top slide was clamped down by two T-bolts, with heads held

in a circular T-slot machined in the cross slide, and its tool-holding T-slot set at an angle.

Unfortunately the cross slide was of the "short" type, a design that guaranteed wear would be

concentrated on the front and middle section of its ways. An unusual fitting was hinged swarf guard

at the back that could be raised to aid lubrication of the feed screw.

The tailstock was suitably massive and

Although a finely engineered piece of work, in true LeBlond fashion, and with easy-to-use controls

the same speed range could have easily been achieved without the Dual-Drive headstock by

conventional gearing and a 2-speed electric motor - though perhaps the absence of gear-chatter

marks on very fine surface finishes turned with the smooth-running V-belts was thought to be

worthwhile.

Tony Griffiths

Inside the Dual-drive's screwcutting gearbox

Rear of the Dual-drive's apron

LeBlond "Dual-Drive" Lathe Mk. 1

LeBlond Lathes - USA

Handbooks are available for many LeBlond lathes. Please email for

details

LeBlond have long been regarded as a maker of high quality machines; their

claim was not that they produced "Toolroom-standard" machines but simply, to

quote from their publicity literature, "better lathes". And they were better; the

US government made extensive use of them in military repair shops and some

are known to have lasted through forty years of heavy use with complete

reliability.

In amateur circles the LeBlond Regal 10" , part of the "Regal" series introduced

in 1931 to compensate for a flagging industrial market, is especially famous and

was exported in large numbers during World War 2 and so is well known both in

its home country and in Great Britain (this lathe can be found on a separate

section of the site). Having to appeal to non-industrial users - repair shops and

wealthy amateurs - the "Regal" lathes were much lighter than the company's

previous products and had separate catalogs devoted to them. The heavier

LeBlond lathes (the smallest of which, until the late 1920s, was of 15" swing,

are illustrated on the pages with hyper-links at the top of this page. An

interesting account of LeBlond's later years and observations about some of their

post WW2 machines can be found here.

Typical of the pre-WW2 LeBlond lathes was the 17" Heavy Duty. Availab

both open-belt and geared-headstock versions it was almost identical in ap

to both smaller and larger

"Single-Pulley Driven Headstock" - external view

On LeBlond Lathes of 15" to 23" capacity, the front and rear spindle bearing were

of different construction. The front bearing, being the more heavily loaded of the

two, was formed by shrinking a hardened-steel sleeve onto the spindle and then

finish grinding it in position. The bearing then ran directly in the cast iron of the

headstock - an ideal combination of surfaces for long and reliable operation. The

left-hand bearing, being much less heavily stressed was formed from traditional

"babbit " bearing metal. LeBlond claimed that the two bearings would wear at the

same rate, and so keep the spindle in as near perfect alignment as possible -

however, they did acknowledge that both the design and material specified for

headstock bearings were contentious matters - and were therefore prepared to

supply disbelievers with either phosphor bronze or babbit bearings as required.

"Single-Pulley Driven Headstock" - an internal view. The geared headstock provided

twelve spindle speeds, with the use of thirteen gears, all of which were made of nickel-

alloy steel, heat treated and hardened- - the bores being ground concentric with the pitch

circle after heat treating to ensure that they ran as quietly as possible.

The headstock components were of robust proportions, the gears being unusually wide

faced and of large diameter.

On the open flat-belt drive headstocks LeBlond employed a form of clutched double backgear which, once

engaged, could be instantly changed between the two low-speed ratios by the single stroke of a lever. This ga

lathe three speed ranges: open high, intermediate low and slow.

On the very largest LeBlond lathes of 33" and 36" capacity, a "Triple backgear" was offered that was, in effect, a

backgear built onto a backgear. This arrangement enabled the lathes to run not only at the high speeds necessary

for smaller work, but also at the very low speeds which the cutting tools of the day demanded when taking heavy

cuts on the largest diameter the lathes could accommodate.

Massively constructed, the bed of the LeBlond lathe featured a much steeper angle to the front way than that provided

by other makers - this was designated by the makers as their "Improved Compensating V" and was claimed to overcome

the limitations that were evident in the standard American inverted V arrangement with its equal-sized ways of very

limited area. The back of the carriage ran on a flat way (and was retained by a flat gib underneath, copying "English"

practice) whilst the top of the front ways were exceptionally broad and the Vs arranged at 15 degrees and 70 degrees

which, it was claimed, prevented the carriage from trying to climb over them under heavy cuts.

Heavily-built LeBlond 25" lathe of 1921 clearly showing the bed

section with its steeply-racked, wide-surface "inverted V"

construction. Note the rack-driven tailstock - no need to send for

two apprentices to push it along the bed.

Like many makers of the time LeBlond seemed content to fit what

today would be considered very undersized micrometer dials to

the compound-slide feed screws.

A box-section casting was used for the LeBlond apron, a design that

supported the various gear-carrying shafts at both ends. Tongued at both

ends for accurate location, the Apron was fastened to the saddle with four

bolts. All gears were machined from drop forgings and their shafts

hardened and ground. A single, positive-action lever with a spring-plunger

indent moved though a quadrant to engage either power sliding or

surfacing - and the feed could be instantly tripped in or out by another

lever mounted centrally on the apron front.

Leadscrews were roughed out on a threading lathe and then allowed a

period of time for the strains caused by machining to equalise; they were

then finished on a lathe fitted with a precision master screw. Because a

separate power shaft was used for sliding and surfacing feeds, the accuracy

of the leadscrew was not destroyed in day-to-day work.

If there is one feature that immediately makes a LeBlond lathe

recognisable it is the "barrel" selector" screwcutting gearbox . The

basic design was used from 1920 onwards across the entire range

from 10" to 25". It was a very compact unit, using a barrel and

quadrant lever on the larger lathes - and the barrel together with a

horizontal lever and sliding "Norton" type gear on the later 10"

Regal. By WW2 the lathes of 17" and above were fitted with a

modified design with a top lever of a more conventional appearance.

LeBlond Screwcutting gearbox - the internals.

The LeBlond "Portable Engine Lathe" was made in 15", 17" and 19" swing versions and advertised as being suitable for

use in "railway workshops, arsenals and battleships" - though one hopes that a method of locking the wheels was provided

for when sea conditions were other then a flat calm ..

Although not specialising in the type, LeBlond also produced a lathe

advertised as a "Toolroom" model. Any lathe in the range could be

supplied to this specification which, besides selective assembly also

included a range of options including taper turning, draw-in collets,

coolant and chip tray and a relieving or backing off attachment.

LeBlond "Style D" motor mount.

A very early installation of an integral motor drive unit on the back of a

lathe. Quite why it took so long for this neat, space saving deign to be

adopted by all lathe manufactures is a mystery.

Makers of lathes with open, flat-belt drive headstocks who hesitated to

develop geared-head machines, yet wanted to include a self-contained

machine in their line, had little choice but to mount individual electric

motors and their countershaft above the spindle line so making the lathes

even more top heavy and cumbersome in appearance.

With the coming of V belts compact, short-centre drives were possible

and proved very popular for commercial installation running production

machinery - although the machine above used not a belt, but a "Morse

Silent Chain". Some toolroom lathes, however, continued to rely to this

day upon the much smoother running flat belt.

Copying Attachment. This followed the usual design but, instead of the tracing tool being kept in contact (with the shape

to be copied) by hydraulic power as on more modern lathes, a very heavy weight was used, suspended by a cable over

pulleys and operating through the cross-feed screw. The weight was stationary, and so relieved the carriage of extra

weight, whilst the thrust from the cut was taken on two heavy studs pressed directly into the carriage casting.

Produced as a flat plate, the form to be copied was bolted to an angle bracket on the rear of the lathe bed; the bracket was

adjustable though a small arc to allow for final setting of the work after trial cuts had been made.

"Double Screw" American

toolpost mounted on the sta

compound slide rest. This h

duty tool holder was specif

standard on the 21" and lar

machines

"Double Screw" American pattern

toolpost mounted on a plain cross slide

- an ideal set-up for heavy-duty plain

work where the inherent flexibility of

the top slide was eliminated by not

using it ..

An alternative to the Plain

Cross slide was the

"Round-block Toolholder"

which converted the

standard cross slide into a

similarly robust unit

suitable for heavy turning.

Rise and Fall Slide Rest and Toolpost

Once the tool was locked into its holder, its height could

be finely adjusted by means of the ramp-mounted slide. A

thread-chasing stop (illustrated) was available as an extra.

This very unusual toolholder, the "Full Swing Rest" was

designed to be clamped to the wing of the lathe saddle

and, as it name implied, enabled the maximum turning

capacity of the machine to be used.

It could also be used in conjunction with the regular

toolholders when it was required (or possible) to turn two

steps at once.

One way of getting a reasonably-sized cross-feed dial was to specify

the very unusual "Multiple Positive Cross Stop", which was available

as an extra on any lathe up to and including the 36" swing model.

The stops were built into the cross-feed dial housing - which had to be

exceptionally large to accommodate the mechanism - and provided

with adjustable indicator clips for quick reading.

The stops consisted of four hardened and ground discs, each with a

projection on its periphery, which engaged against pins which can be

seen protruding through the body of the housing.

The discs could be adjusted to engage the stop pins at any

predetermined distance from .001" to one or more full turns, after

which they were locked together by wing nuts at the front of the hand

wheel. It was claimed that the stops would duplicate diameters to

within .001".

While one of the most useful features any lathe can possess is an

automatic, pre-set trip for the power feeds the LeBlond "Multiple

Automatic Length Stop" went one stage further - and offered rapid and

accurate turning of multiple shoulders.

The bar that carried the trip stops was bolted to the front of bed; the

tripping mechanism was located in the apron itself and consisted of a

hardened-steel clutch which engaged and disengaged the feed mechanism

The trip lever for the automatic stops was put in a downward position and

the feed engaged. The carriage then feed along the bed until it engaged the

first trip dog, which threw out the drive. The drive was then re-engaged

and the operation repeated for any number of shoulders as stops were

provided for.

If the lathe was also fitted with the Multiple Cross Stop then different

diameters could easily be preset for each "trip" - and much time saved.

The "Multiple Positive Length Stop" was for the accurate, pre-set spacing

shoulders on long bars. The spacing bar and holder were attached to the ca

and the spacing lever adjusted along the front shear of the bed and clampe

desired position. The bar was made up with the required number of "notc

spaced so that they corresponded to the shoulders required on the shaft to

turned. When the work was finished the shaft could, of course, be remove

preserved for future repetition of the job.

When the bar was not being used it could be given a half turn - so that the

index lever did not engage with the slots - and the lathe used normally.

Designed to do under power what had previously been done by hand the

Relieving Attachment was used to accurately relieve (or back off) the teet

taps, cutters, hobs and milling cutters. The device was fastened to the top

gearbox and power taken from a gear on the end of the headstock spindle

then through interchangeable gears carried on a quadrant arm. The unit co

be left in place - and did not interfere with the normal operation of the lath

The drive passed through two knuckle joints, and a telescopic shaft, to the

actuating mechanism which consisted of a hardened and ground cam, carr

between bronze bearings in a compound-swivel rest, which moved agains

hardened steel roller carried in a sliding compound rest nut. The cam gave

standard top slide a push forwards and a heavy coil spring pushed it back,

imparting an oscillating motion to the slide. The return spring encircled a

attached to the sliding nut, and had two adjusting nuts at either end by wh

the amount of relief needed could be adjusted.

The adjusting nuts were also used to draw the compound rest nut and rolle

away from the cam and hold it solidly against a finished surface and, beca

the cam then revolved idly and the top slide remained stationary, the top s

could then be used in the normal way.

The number of flutes that could be relieved with the changewheels supplie

were 2, 8, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 18, 14, 15, 16, 18, 20, 22, 24, 26, 28,

and 82 with the different gear combinations shown on an engraved plate. T

attachment was designed to be factory fitted to any LeBlond lathe from 15

21" swing.

E-Mail Tony@lathes.co.uk

Home Machine Tool Archive Machine Tools For Sale & Want

Machine Tool Manuals Machine Tool Catalogues Belts Accesso

LeBlond Lathes - USA

Regal Lathes LeBlond Dual Drive lathes

LeBlond NK Heavy-duty Models

Handbooks are available for many LeBlond lathes.

Please email for details

E-MAIL Tony@lathes.co.uk

Home Machine Tool Archive Machine Tools For

Sale & Wanted

Machine Tool Manuals Machine Tool Catalogues Belts

LeBlond Regal Lathes

Operation, Maintenance & Parts Manuals are available for

all the Regal lathes.

Email for details

Regal lathes 1930s to 1946 Regal Lathes 1946 to late

1950s

Regal lathes late 1950s onwards

LeBlond Dual Drive LeBlond home page Regal 10-inch

photographs

A very successful manufacturer, the R. K. LeBlond Machine

Tool Company of Cincinnati, Ohio had, since its founding in

1888, outlived five production plants, with each in turn being

replaced by a bigger and better-equipped facility. By 1929 their

440,000 square-foot factory, set in pleasant grounds at the

corner of Madison and Edwards Roads, Hyde Park, was

employing some 900 people all devoted exclusively to the

manufacture of heavy industrial lathes from ordinary "engine"

types (backgeared and screwcutting to the UK reader) to

massive 60,000 pounds crankshaft-turning models equipped to

finish all eight crankpins on an eight-cylinder engine at the rate

of twenty cranks per hour. Whilst that might be considered a

modest achievement set against 21st century machining times it

was, for the era, a significant technical achievement and enabled

LeBlond to offer state-of-the-art manufacturing equipment to

automobile and other mass-production makers. Unfortunately,

in 1930, LeBlond faced, as did all manufacturing industry, the

Great Depression and its accompanying slump in trade. In order

to survive the company decided to widen its market and

introduced, alongside it's long-established range of heavy

engine lathes, a range of lighter, more-affordable models

designed to appeal to the lower end of the market: better-off

home-experimenters and model-makers, research departments,

training schools, motor-repair garages, the self-employed and

similar buyers. However, even with keen pricing and the

backing of the respected LeBlond name, success could not be

guaranteed for the new range, branded "Regal", entered a

section of the industry already dominated by, amongst others,

such well-established makers as South Bend, Sheldon, Barnes

and Seneca Falls. Thankfully for the shareholders, LeBlond's

approach was well thought out: although the lathes would only

weight from one-third to one half as much, they would all

mirror the quality and desirability of their industrial equivalents.

They would have the most up-to-date specification possible, be

easy to operate, come equipped ready for use and be introduced

as a complete range with 10, 12, 14, 16 and 18-inch swings

(actual capacity was always slightly more) Headstocks would

be all-geared (no alternative flat or V-belt drive versions would

be offered) with lever-operated speed changes and the exclusive

use of built-on, self-contained motor drives with power

transmitted to the headstock input shaft by the use of the

recently-introduced (circa 1930) V-belt. All would have a

proper screwcutting gearbox, a separate feed-rod to drive the

sliding and surfacing feeds (engaged by a fool-proof, snap-

engagement system) and a robust carriage assembly whose

design was not compromised by having to allow for a gap bed.

As the sole concession to hard times the cheapest model, the 10-

inch, could be had to special order without the power cross feed

and with a set of changewheels for screwcutting. Popular in the

UK during WW2 (and with many examples still in use in the

21st century) production of the 10-inch was to end in 1945 -

though other models, constantly developed and refined,

continued into the 1980s. Notable changes in design occurred in

approximately 1946 and (in very much more radial form) during

the late 1950s when an even wider variety of models and types

was introduced. The two earlier types are easily distinguished

by the disposition of their headstock controls and the final

model (in standard, Servo-shift and sliding-bed forms) by its

modern, very angular lines. Although the larger Regal lathes in

21 and 24-inch sizes were enormous machines, comparable in

some respects to the proper very heavy-duty LeBlond engine

lathes, unfortunately there was an attempt to stretch them

beyond their limits with the introduction of what amounted to

very large-bore "Oil Country" headstocks.

In the 1980s LeBlond had tried to produce their lathes,

particularly the lighter "Regal" models, all (or in part) at a low-

cost plant in Singapore. This was the last gasp for the company

and, when the new Japanese owners, Makino, had finished with

them, they had built their last proper engine lathes.

Unfortunately the patterns, core boxes, jigs and fixtures had all

been shipped to Singapore and, when the end came, all were

ordered to be burned or scrapped - a decision that precluded

anyone from trying to resurrect the machines.

Continued below:

LeBlond Regal 10-inch

Continued:

Early Models

Made from close-grained iron mixed with steel and nickel the

bed carried inverted "V" and flat ways (separate for carriage and

tailstock) with the front and back walls in the form of I beam

sections joined by closely-spaced cross girths. The beds were

first rough machined and then seasoned for some months before

being finished planed in batches and then hand scraped to a

"master". Each saddle assembly was also scraped to its

particular bed and then, with the apron fitted, the carriage rack

located to the bed with screws and dowel pins. An enormous

variety of bed lengths was available that gave between-centres'

capacities of 18", 24", 30", 36" and 42" for the 10-inch, 12-inch

and 14-inch models (with an additional 66-inch model for the

12-inch and 14-inch swing lathes only) whilst the 16-inch and

18-inch could be had with a capacity of 30", 42", 54", 78" and

102" - and 126" for the 18-inch model only.

On all sizes of "Regal" the headstock was of similar

construction with a box-form casting, closed at the top (with a

heavy iron cover), reinforced under the main spindle bearings

and with an oil bath in the base to lubricate the gears by splash.

LeBlond recommended: "a medium grade of machine or

automobile oil" - though this would have been before the

addition to motor oils of chemicals unfriendly to machine-tool

components left standing unused for long periods. The spindle

bearings, phosphor bronze but tinned with a layer of high-

quality "babbit", were retained by heavy caps locked down by

Allen-headed socket screws. The bearings were hand scraped to

the spindle and (to keep out any particles from worn gears)

lubricated from separate flip-top oilers fitted with felt filter

pads. Although the very powerful LeBlond industrial engine

lathes would have had their main headstock gears made from

drop forgings, on the Regal line all were made instead from

steel blanks. After the machining the bore, keyways, splines,

sides and cutting of the teeth, each gear was burnished before

being subjected to a hardening heat treatment process. Other

than those on the main spindle, headstock gears ran on shafts

spinning in plain phosphor bronze bearings fed with splash oil

that had been collected in reservoirs and filtered through felt

pads. The final drive gears were of helical form and provided

not only an exceptionally quiet and smooth-running headstock

when new but also when well worn and badly abused. 8 spindle

speeds were provided with a high/low lever on the right of the

headstock's front face and a four-speed selector to the left with

both indexing through positions located by spring-loaded

plungers. To aid speed changes (and engagement of tumble

reverse) a polished-rim handwheel was formed as part of the

headstock drive pulley and arranged to protrude through the

cast-iron belt-run cover. By gently moving the wheel back and

forth the operator was able to persuade the gears into mesh as

he moved the headstock selector levers. Although rather small

on early versions the wheel was later increased in size to almost

the full diameter of the pulley.

On stand-mounted lathes the hinged motor-plate (adjustable for

belt tension) was bolted to the back of the headstock-end leg

and on bench machines to the rear of an extended headstock-

end foot. Although underdrive systems with the motor inside a

cabinet leg had been in production for some time the

importance of this new system, with its deceptive neatness,

simplicity and economy cannot be understated for it quickly

became an industry standard, being copied by almost all other

makers of similar machines. A further important point was the

provision as standard of an electrical reversing switch, mounted

in a convenient position on top of the headstock: when the lathe

was delivered it could be put to work straight away and its

position in the factory of workshop determined not by where a

cumbersome countershaft could be mounted, or the line-

shafting picked up, but where was most convenient and

efficient.

Continued below:

Early Regal headstock with 2-lever control of spindle speeds

Continued:

In order to give maximum support to the cutting tool the saddle

was fitted with four long, equal-length wings and the cross-slide

(unfortunately of the short type that tended to wear just the front

and middle part of its ways) arranged to sit on its exact centre

line. This theoretically desirable state of affairs was permitted

by both setting the front and back faces of the headstock

inwards - and so allowing the saddle wings to run on past the

spindle nose - and the absence of an gap in the bed, an

undeniably useful feature but one that brings complications in

its wake.

The apron of the 10", 12" and 14" models was of identical

design and, although of single-sided construction, was heavily

built, tongued on the ends to locate to the saddle, clamped by 4

bolts and incorporated proven features from the maker's larger

engine lathes. The gears were all cut from the solid and

mounted on good-sized studs that ran in long, wear resistant

housings. To ensure as rigid an assembly as possible the apron

was dowelled to the saddle and clamped by a recent invention,

socket-headed Allen screws, whose clamping force was so

much easier to exploit that the slot-headed screws used by so

many other makers that had to be tightened by nothing more

than a glorified screwdriver. The arrangements for power

sliding and surfacing feeds were well though out, of robust

simplicity, and known for a long and trouble-free life. A feed-

rod, slotted to pick up a key carried inside a long sleeve held in

a bearing on the inside face of the apron, emerged from the

screwcutting gearbox. On the end of the sleeve was a small

pinion that drove a large crown wheel on whose supporting

shaft was cut a wide-faced pinion. The drive was made to pass

from the wide pinion to either the cross-feed screw or the bed

rack by means of a 3-position sliding gear the knurled head of

which emerged through the face of the apron as a selector for

the operator to manipulate. With the selector pushed in power

sliding was achieved (up and down the bed) with it pulled fully

out power cross feed was selected. Only in its middle position

would it safely allow the leadscrew clasp nut to be closed for

screwcutting. Whilst the push-pull button selected the

appropriate feed direction for engagement and disengagement a

separate lever with two spring-indexed positions was used that

simply slide the pinion into and out of engagement with the

crown wheel. Unlike the "safety" wind-in-and-out clutches used

by some makers that required the operator to anticipate the

disengage position and then unscrew a control knob to stop the

feed on the LeBlond the action was instantaneous and

absolutely safe. To prevent damage to the gears by, for

example, running the carriage into the chuck, the feed-rod on

the 10, 12 and 14-inch models was in two parts but connected at

a socket where a cross drilling on the inner shaft held a

powerful spring that pushed on a ball bearing at each end. The

balls sat in shallow sockets drilled in the outer shaft and, under

normal conditions, the two parts rotated as one. In the case of an

overload the spring-loaded balls allowed the shafts to slip but,

as soon as the stress was removed, the mechanism automatically

reconnected the drive. On the 16 and 18-inch versions a simple

shear pin was provided in the feed-rod drive, the excuse

advanced being that the more experienced craftsman employed

on such large lathes would be unlikely to make simple handling

errors.

The apron of the larger Regal models was an exact duplicate of

that used on the company's heavy-duty engine lathes. Of

double-wall construction, made from a single casting and

braced by cross ribs, LeBlond claimed that its patented design

contained around 50% fewer parts than generally used by

competing manufacturers and was thus far less likely to go

wrong or suffer wear of small but critical components. The

main drive gears were made from drop-forged steel and ran on

hardened and ground shafts with the bed rack engagement gear

(the rack pinion, a source of weakness on many lathes) being in

chrome nickel alloy steel normalised and hardened. The same

sort of large crown wheel was used but driven by either of two

pinions, one at each side and selected by a lever on the apron

face, which had the effect of causing the carriage to move left or

right without having to reset the headstock-mounted tumble-

reverse mechanism. In the centre of the assembly was a "spider

clutch", a ring of fine teeth, used to engage and disengage the

drive. Although of different internal design the apron used

external controls that mirrored those on the smaller machines:

there was a similar kind of in-out feed selector button and one

easily-operated lever (connected to the spider clutch) to

instantly start and stop the feeds - with no friction device to

hamper the process.

Continued below:

Early Regal carriage assembly

Continued:

Of utterly conventional design the compound slide rest had (the

usual failing at the time) rather small friction micrometer dials,

gib strips adjusted by pusher screws and a "short" cross slide

that tended to concentrate wear the front and middle part of its

ways. The top slide was clamped down by two T-bolts with

their heads held in a circular T-slot machined in the cross slide.

The graduations to indicate the degree of swivel were on the

inside front edge, and hence difficult to read, but its tool-

holding T-slot was usefully-large.

On all sizes of the first Regal lathe the screwcutting

arrangements were identical - with an output gear on the spindle

driving through an externally-mounted tumble-reverse

mechanism (a reverse plate in LeBlond terminology) with the

gears in steel and running on hardened studs. Whilst it was not

unusual for smaller lathes to have the tumble gears on overhung

shafts (and continues so to this day) on larger machines, from

many makers, they were generally fitted inside the headstock

where, better supported and running in oil, they had a far easier

time. After WW2 LeBlond redesigned the Regal headstock so

this improvement was included and also removed the quadrant-

arm mounted sliding gear (that provided a change between fine-

feeds and screwcutting) and built that mechanism into the

headstock as well. The later, improved headstocks are easily

identifiable by a pair of small levers, set one above the other

between the main spindle speed-change levers.

Shared by the 10", 12" and 14" Models, the same ingeniously-

designed quick-change screwcutting and feeds gearbox was

used and consisted of a separate unit bolted to the front of the

bed. The 20-degree pressure angle gears were all in steel

(though not hardened) and lubrication of the box depended upon

the whim of the operator who had to swing aside a protective

plate on the top and use an oil can to fill a small reservoir from

which lubricant tricked down various holes to appropriate

places. An eight-position, spring-plunger selector slid along a

long cylinder and protruded from the face of the box. It carried

a captive gear that was permanently meshed with a long gear on

the inside of the cylinder and could also be engaged with any of

eight feed gears on an intermediate shaft. A horizontal, three-

position lever at the bottom of the box and provided three

different ratios for each of the eight positions on the tumbler

(giving twenty-four in total) whilst a two-position sliding gear

on the gear train from the headstock (its head protruding

through the gear guard) doubled the number of feeds and

pitches to a total of forty-eight. Pitches varied from 2 to 112

t.p.i and feeds from 0.0025" to 0.144" per revolution of the

spindle. Whilst the drip-lubricated screwcutting and feeds box

used on the larger models was of a similar appearance to that

used on the smaller versions its internal design was more akin to

those employed on the company's larger commercial lathes, a

design so successful that the company was able to proudly

claim that the number of gearbox repair parts requested over 25

years been "practically nothing". A four-position selector on the

face of the box increased the total number of threads and feeds

to 56. Pitches varied from 1.5 to 184 t.p.i and longitudinal feeds

from 0.001" to 0.125" per revolution of the spindle.

Unlike many machine-tool manufactures, including South Send,

who bought their leadscrews in from specialist makers LeBlond

made their own from lengths of a high-carbon steel bought in as

ground stock. The left-hand Acme-form thread was first

roughed out on a thread milling machine and the leadscrew then

rested for a time sufficient to relieve the strains of the initial

machining. It was then finished by a "thread-chasing" process

on a special lathe equipped with a precision leadscrew itself cut

from a certified Master Leadscrew kept under temperature

controlled conditions. The screw was mounted on the lathe

between ground washers with the thrust arranged to be taken at

the better-supported gearbox end when cutting right-hand

threads. Like other parts of the various models the leadscrews

were properly sized according to their duties: 8 t.p.i by "

diameter on the 10-inch model; 6 t.p.i. by 1" on the 12-inch and

14-inch and 4 t.p.i. by 13/16" on the 16-inch and 18-inch

versions.

Continued below:

Apron as used on the first Regal 10, 12 and 14-inch models

Continued:

The tailstock was typical of LeBlond practice: hand-scraped to

the bed and built so that the upper section could be off-set on

the sole plate for the turning of shallow tapers, the casting was

also carefully shaped so that when brought up along side the top

slide the latter could still be operated when turning very short

jobs between centres. The Morse-taper spindle was of high

carbon steel, ground finished and marked with ruler graduations

for drilling. It was driven by an Acme thread running though a

bronze nut and locked by a substantial lever that closed down

opposing clamps.

The company's move into a new product line at the beginning

of the 1930s proved to be fully justified with the Regals

remaining in production until the early 1960s when they were

replaced by a range carrying the same name but of radically

altered design and very angular, modern styling. Although

during their long production run the lathes remained essentially

the same, after WW2 the 10-inch dropped and the other models

revised with 13", 15", 17", 19", 21" and 24" swings (an

interesting machine introduced at the same time, though it

shared nothing with the Regal, was the ingenious if complex

Dual-Drive. During the 1940s a number of improvements were

made to functionality and durability by including the use of

heavier stands with cast-iron box plinths beneath headstock and

tailstock and offering as extras, various features including

higher speed ranges to take advantage of carbide-tipped tools,

roller-bearing headstocks, gap beds, a one-shot lubrication

system that oiled the apron internals and bed and cross-slide

ways, the useful feed-rod safety coupling extended to the whole

range (instead of just the smaller models) and headstock

spindles fitted with a multi-disc clutch and brake unit operated

by duplicated controls levers on apron and screwcutting

gearbox.

Regal lathes were offered with the usual range of accessories -

chucks, steadies, taper-turning attachments, toolpost grinders,

micrometer carriage stops - as well as an unusual "Millerette"

attachment. Built in three sizes the unit carried a T-slotted table

on which was mounted a worm-and-wheel driven indexing unit

that allowed, besides the usual milling operations, dividing

work and the generation of spur and bevel gears, splines and

slots.

Tony Griffiths

Apron used on the early 10, 12 and 14-inch models

Apron used on the early 10, 12 and 14-inch models

Early 10, 12 and 14-inch screwcutting gearbox

Inside the early 10, 12 and 14-inch screwcutting gearbox

E-MAIL Tony@lathes.co.uk

Home Machine Tool Archive Machine Tools For Sale & Wanted

Machine Tool Manuals Machine Tool Catalogues Belts

LeBlond Regal Lathes

Operation, Maintenance & Parts Manuals are available for all the Regal lathes.

Email for details

Regal lathes 1930s to 1946 Regal Lathes 1946 to late 1950s

Regal lathes late 1950s onwards

LeBlond Dual Drive LeBlond home page Regal 10-inch photographs

Вам также может понравиться

- Metric - Threading Logan LatheДокумент2 страницыMetric - Threading Logan LatheShane RamnathОценок пока нет

- Slotting MachineДокумент32 страницыSlotting Machinesanaashraf91% (11)

- Atlas Mill AccessoriesДокумент1 страницаAtlas Mill AccessoriesGary RepeshОценок пока нет

- Operating: Maintenance ManualДокумент18 страницOperating: Maintenance ManualAnonymous reYe6iCCОценок пока нет

- 3 PhaseДокумент9 страниц3 PhaseArnulfo LavaresОценок пока нет

- Court Documents From Toronto Police Project Brazen - Investigation of Alexander "Sandro" Lisi and Toronto Mayor Rob FordДокумент474 страницыCourt Documents From Toronto Police Project Brazen - Investigation of Alexander "Sandro" Lisi and Toronto Mayor Rob Fordanna_mehler_papernyОценок пока нет

- LeBlond's Dual Drive Lathe SmallДокумент28 страницLeBlond's Dual Drive Lathe Small4U6ogj8b9snylkslkn3nОценок пока нет

- A Guide to Motor-Cycle Design - A Collection of Vintage Articles on Motor Cycle ConstructionОт EverandA Guide to Motor-Cycle Design - A Collection of Vintage Articles on Motor Cycle ConstructionОценок пока нет

- Fordson Major ManualДокумент47 страницFordson Major ManualHassan GDOURAОценок пока нет

- Metal LatheДокумент25 страницMetal Lathebogesz68Оценок пока нет

- Ford Old TimersДокумент25 страницFord Old TimersJan-Erik Kaald HusbyОценок пока нет

- Riding Mower PartsДокумент17 страницRiding Mower PartsDwight MorrisonОценок пока нет

- Bonfiglioli Geared MotorДокумент584 страницыBonfiglioli Geared MotorProdip SarkarОценок пока нет

- Shaper Used As Surface GrinderДокумент1 страницаShaper Used As Surface Grinderradio-chaserОценок пока нет

- Modification and Development of Work Holding Device - Steady-RestДокумент6 страницModification and Development of Work Holding Device - Steady-RestInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology100% (1)

- The Shape of The Cone of The Twist Drills Unit-2Документ5 страницThe Shape of The Cone of The Twist Drills Unit-2Akesh KakarlaОценок пока нет

- US CAT Niagara Cutter Catalog GT17-136Документ342 страницыUS CAT Niagara Cutter Catalog GT17-136MANUEL VICTORОценок пока нет

- BME Lecture 5 ShaperДокумент6 страницBME Lecture 5 ShaperRoop LalОценок пока нет

- Jdsw51a Usb Mach3 (Blue) - 5aixsДокумент36 страницJdsw51a Usb Mach3 (Blue) - 5aixsabelmil123Оценок пока нет

- p005 Compact Equipment Tires BroДокумент8 страницp005 Compact Equipment Tires BroAkhmad SebehОценок пока нет

- Lathes and Lathe Machining OperationsДокумент11 страницLathes and Lathe Machining OperationsJunayed HasanОценок пока нет

- Making A Spur GearДокумент9 страницMaking A Spur GearHaraprasad DolaiОценок пока нет

- Maag Gear Shaper CutterДокумент9 страницMaag Gear Shaper CutterBence Levente Szabó100% (1)

- Lathebeddesign00hornrich PDFДокумент56 страницLathebeddesign00hornrich PDFLatika KashyapОценок пока нет

- Mini Mill Users GuideДокумент28 страницMini Mill Users Guidechriswood_gmailОценок пока нет

- Ebook Tapping Away Guide To Tapping and Threading Xometry SuppliesДокумент19 страницEbook Tapping Away Guide To Tapping and Threading Xometry SuppliesAli KhubbakhtОценок пока нет

- Bridgeport J-Head Series I RebuildДокумент69 страницBridgeport J-Head Series I RebuildBasil Hwang100% (1)

- The Synthesis of Elliptical Gears Generated by Shaper-CuttersДокумент9 страницThe Synthesis of Elliptical Gears Generated by Shaper-CuttersBen TearleОценок пока нет

- Ralph Patterson Tailstock Camlock 2Документ13 страницRalph Patterson Tailstock Camlock 2supremesportsОценок пока нет

- AVHC Quick StartДокумент58 страницAVHC Quick StartAndres Jose Amato TorresОценок пока нет

- MI-1220 XL Manual 2008Документ115 страницMI-1220 XL Manual 2008James BanksОценок пока нет

- Pioneer Avh-P3100dvd p3150dvd SMДокумент190 страницPioneer Avh-P3100dvd p3150dvd SMRogerio E. SantoОценок пока нет

- (Metalworking) Welding and MachiningДокумент1 767 страниц(Metalworking) Welding and MachiningEugeneОценок пока нет

- Lathe Schaublin 102n 9982Документ1 страницаLathe Schaublin 102n 9982FranciscoОценок пока нет

- PowerTIG 250EX 2016Документ32 страницыPowerTIG 250EX 2016Bob john100% (1)

- Torno LoganДокумент16 страницTorno LoganLaura Díaz B.100% (1)

- Capstan & Turret LatheДокумент27 страницCapstan & Turret LatheMuraliОценок пока нет

- Tapers and Taper TurningДокумент4 страницыTapers and Taper TurningSayanSanyalОценок пока нет

- Planer Quick Return MechanismДокумент21 страницаPlaner Quick Return Mechanismlalagandu100% (1)

- 149-Workshop Hints & TipsДокумент1 страница149-Workshop Hints & TipssyllavethyjimОценок пока нет

- Four Cylinder Air Engine Dwg.Документ15 страницFour Cylinder Air Engine Dwg.Jitendra BagalОценок пока нет

- Cutting Tools & Tool HoldersДокумент38 страницCutting Tools & Tool HoldersWilliam SalazarОценок пока нет

- Lathes and Lathe Machining OperationsДокумент18 страницLathes and Lathe Machining Operationssarasrisam100% (1)

- 8454 PDFДокумент72 страницы8454 PDFjon@libertyintegrationcomОценок пока нет

- Catalogo EBC 2011Документ524 страницыCatalogo EBC 2011Diego Solano ArayaОценок пока нет

- AnacondaДокумент4 страницыAnacondaDarshan PatelОценок пока нет

- WheelhorseTractor 1978 B C D SeriesServiceManual 810063RlДокумент70 страницWheelhorseTractor 1978 B C D SeriesServiceManual 810063RlJamesОценок пока нет

- Threads and ChangegearsДокумент36 страницThreads and ChangegearsRC VilledaОценок пока нет

- Gear Grinding: SoftwareДокумент68 страницGear Grinding: SoftwareTungОценок пока нет

- QcadCAM Tutorial enДокумент12 страницQcadCAM Tutorial enartisanicviewОценок пока нет

- WErbsen CourseworkДокумент562 страницыWErbsen CourseworkRoberto Alexis Rodríguez TorresОценок пока нет

- Fresadora #12Документ15 страницFresadora #12jmtortu100% (1)

- South Bend 9" Compound Slide Screw Fabrication For A Large Dial/Thrust Bearing Conversion by Ed Godwin 8 December, 2007Документ16 страницSouth Bend 9" Compound Slide Screw Fabrication For A Large Dial/Thrust Bearing Conversion by Ed Godwin 8 December, 2007asdfОценок пока нет

- Inside Type Outside Type: Fit. 113. Turain! e Steet Shaft Mounted Betw M CeotercДокумент22 страницыInside Type Outside Type: Fit. 113. Turain! e Steet Shaft Mounted Betw M CeotercRick ManОценок пока нет

- MigrationДокумент6 страницMigrationMaria Isabel PerezHernandezОценок пока нет

- Independence of Costa RicaДокумент2 страницыIndependence of Costa Ricaangelica ruizОценок пока нет

- Pr1 m4 Identifying The Inquiry and Stating The ProblemДокумент61 страницаPr1 m4 Identifying The Inquiry and Stating The ProblemaachecheutautautaОценок пока нет

- Checklist of Requirements of Special Land Use PermitДокумент1 страницаChecklist of Requirements of Special Land Use PermitAnghelita ManaloОценок пока нет

- 5 L&D Challenges in 2024Документ7 страниц5 L&D Challenges in 2024vishuОценок пока нет

- SyerynДокумент2 страницыSyerynHzlannОценок пока нет

- Due Books List ECEДокумент3 страницыDue Books List ECEMadhumithaОценок пока нет

- Wa0006.Документ8 страницWa0006.Poonm ChoudharyОценок пока нет

- Grill Restaurant Business Plan TemplateДокумент11 страницGrill Restaurant Business Plan TemplateSemira SimonОценок пока нет

- Chronology of Events:: Account: North Davao Mining Corp (NDMC)Документ2 страницыChronology of Events:: Account: North Davao Mining Corp (NDMC)John Robert BautistaОценок пока нет

- Basic Elements of Rural DevelopmentДокумент7 страницBasic Elements of Rural DevelopmentShivam KumarОценок пока нет

- Unit 4: Alternatives To ImprisonmentДокумент8 страницUnit 4: Alternatives To ImprisonmentSAI DEEP GADAОценок пока нет

- MF 2 Capital Budgeting DecisionsДокумент71 страницаMF 2 Capital Budgeting Decisionsarun yadavОценок пока нет

- Solaris Hardening Guide v1Документ56 страницSolaris Hardening Guide v1GusGualdОценок пока нет

- SBFpart 2Документ12 страницSBFpart 2Asadulla KhanОценок пока нет

- Intro To LodgingДокумент63 страницыIntro To LodgingjaevendОценок пока нет

- Accaf3junwk3qa PDFДокумент13 страницAccaf3junwk3qa PDFTiny StarsОценок пока нет

- Promises From The BibleДокумент16 страницPromises From The BiblePaul Barksdale100% (1)

- A Win-Win Water Management Approach in The PhilippinesДокумент29 страницA Win-Win Water Management Approach in The PhilippinesgbalizaОценок пока нет

- D3Документ2 страницыD3zyaОценок пока нет

- Federal Ombudsman of Pakistan Complaints Resolution Mechanism For Overseas PakistanisДокумент41 страницаFederal Ombudsman of Pakistan Complaints Resolution Mechanism For Overseas PakistanisWaseem KhanОценок пока нет

- Rock Type Identification Flow Chart: Sedimentary SedimentaryДокумент8 страницRock Type Identification Flow Chart: Sedimentary Sedimentarymeletiou stamatiosОценок пока нет

- PMP Chapter-12 P. Procurement ManagementДокумент30 страницPMP Chapter-12 P. Procurement Managementashkar299Оценок пока нет

- Team 12 Moot CourtДокумент19 страницTeam 12 Moot CourtShailesh PandeyОценок пока нет

- Summer Anniversary: by Chas AdlardДокумент3 страницыSummer Anniversary: by Chas AdlardAntonette LavisoresОценок пока нет

- Divine Word College of San Jose San Jose, Occidental Mindoro College DepartmentДокумент13 страницDivine Word College of San Jose San Jose, Occidental Mindoro College DepartmentdmiahalОценок пока нет

- Albert Einstein's Riddle - With Solution Explained: October 19, 2009 - AuthorДокумент6 страницAlbert Einstein's Riddle - With Solution Explained: October 19, 2009 - Authorgt295038Оценок пока нет