Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Primary Prevention of CVD - Diet and Weight Loss

Загружено:

wheiinhy0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

12 просмотров15 страницОригинальное название

Primary Prevention of CVD- Diet and Weight Loss

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

12 просмотров15 страницPrimary Prevention of CVD - Diet and Weight Loss

Загружено:

wheiinhyАвторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 15

Primary prevention of CVD: diet and weight loss

Search date August 2006

Lee Hooper

QUESTIONS

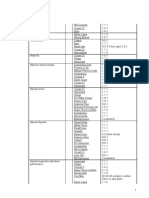

What are the effects of interventions in the general population to reduce sodium intake?. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

What are the effects of a cholesterol-lowering diet in the general population?. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

What are the effects of interventions to increase or maintain weight loss?. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

What are the effects on reducing CVD risk in the general population of eating more fruit and vegetables?. . . 10

What are the effects on reducing CVD risk of antioxidants in the general population?. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

What are the effects on reduction of CVD risk of omega 3 fatty acids in the general population?. . . . . . . . . . . 12

What are the effects on reduction of CVD risk of a Mediterranean diet in the general population?. . . . . . . . . . 12

INTERVENTIONS

ADVICE PROMOTING REDUCTION IN SALT INTAKE

Beneficial

Advice to reduce sodium intake: reduction in cardiovas-

cular disease risk New . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Likely to be beneficial

Advice to reduce sodium intake: reduction in sodium in-

take New . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

ADVICE PROMOTING CHOLESTEROL-LOWERING

Likely to be beneficial

Advice to reduce saturated fat intake: reduction in car-

diovascular disease risk New . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Advice to reduce saturated fat intake: reduction in fat

intake New . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

REDUCING WEIGHT OR MAINTAINING WEIGHT

LOSS

Beneficial

Diets and behavioural interventions to lose weight:

weight loss (effective in combination but not alone) New

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Unknown effectiveness

Diets and behavioural interventions: reduction in cardio-

vascular risk New . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Lifestyle interventions: maintainance of weight loss New

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

Lifestyle interventions: preventing weight gain New . .

8

Training health professionals in promoting weight loss:

weight loss New . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

INCREASING FRUIT AND VEGETABLE INTAKE

Likely to be beneficial

Increase fruit and vegetable intake: reduction in cardio-

vascular disease risk New . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

Unknown effectiveness

Behavioural and counselling interventions: increase in

fruit and vegetable intake New . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

ANTIOXIDANTS

Unlikely to be beneficial

High-dose antioxidant supplements: reduction in cardio-

vascular risk New . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

OMEGA 3

Unknown effectiveness

Omega 3 fatty acids: reduction in cardiovascular risk

New . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

MEDITERRANEAN DIET

Unknown effectiveness

Mediterranean diet: reduction in cardiovascular risk

New . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

Covered elsewhere in Clinical Evidence

Primary prevention of CVD: physical activity

Key points

Diet is an important cause of many chronic diseases.

Individual change in behaviour has the potential to decrease the burden of chronic disease, particularly cardio-

vascular disease (CVD).

This review focuses on the evidence that specific interventions to improve diet and increase weight loss lead to

changed behaviour, and that these changes may prevent CVD.

Intensive advice to healthy people to reduce sodium intake reduces sodium intake, as measured by sodium excretion.

B

l

o

o

d

a

n

d

l

y

m

p

h

d

i

s

o

r

d

e

r

s

BMJ Publishing Group Ltd 2007. All rights reserved. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Clinical Evidence 2007;10:219

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Reducing sodium intake reduces blood pressure, even in people without hypertension.

Advice to reduce saturated fat intake may reduce the saturated fat intake, and multiple advice components reduce

saturated fat intake more.

Reducing saturated fat intake can reduce mortality in the longer term.

Complex combined interventions to lose weight (physical plus dietary plus behavioural) are effective in helping

people lose weight. Simpler interventions are less effective.

We don't know what lifestyle interventions can maintain weight loss or what lifestyle interventions prevent weight

gain, or if training health professionals is effective in promoting weight loss.

We don't know whether diets and behavioural interventions to lose weight reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease.

Increasing fruit and vegetable intake may decrease the risk of cardiovascular disease.

We don't know whether advising people to increase their fruit and vegetable intake will actually increase their

intake.

Taking a high dose of antioxidant supplements (vitamin E and beta carotene) does not reduce mortality or cardio-

vascular events.

We don't know whether omega 3 oil supplementation or advice to increase omega 3 intake can reduce mortality.

We also don't know how effective a Mediterranean diet is at reducing cardiovascular events or deaths in the gen-

eral population.

DEFINITION Diet is important in the cause of many chronic diseases. Individual change in behaviour has the

potential to decrease the burden of chronic disease, particularly cardiovascular disease (CVD).

This review focuses on the evidence that specific interventions to improve diet and increase weight

loss lead to changed behaviour, and that these changes may prevent CVD. Primary prevention in

this context is the long-term management of people at increased risk but with no evidence of CVD.

Clinically overt ischaemic vascular disease includes acute myocardial infarction, angina, stroke,

and peripheral vascular disease. Many adults have no symptoms or obvious signs of vascular

disease, even though they have atheroma and are at increased risk of ischaemic vascular events

because of one or more risk factors. In this review, we have taken primary prevention to apply to

people who have not had clinically overt CVD, or people at low risk of ischaemic cardiovascular

events. Prevention of cerebrovascular events is discussed in detail elsewhere in BMJ Clinical Evi-

dence (see review on stroke prevention).

INCIDENCE/

PREVALENCE

CVD was responsible for 39% of UK deaths in 2002. Half of these were from coronary heart disease

(CHD), and a quarter from stroke. CVD is also a major cause of death before 75 years of age,

causing 34% of early deaths in men and 25% of deaths before 75 years of age in women. CHD

deaths rose dramatically in the UK during the 20th century, peaked in the 1970s, and have fallen

since then. Numbers of people living with CVD are not falling, and the British Heart Foundation

estimates that there are about 1.5 million men and 1.2 million women who have or have had a

myocardial infarction or angina.

[1]

Worldwide, it is estimated that 17 million people die of CVDs

every year, and more than 60% of the global burden of CHD is found in resource-poor countries

(10% of disability-adjusted life years [DALYs] lost in low- and middle-income countries and 18%

in high-income countries).

[2]

The USA has a similar burden of heart disease to the UK; in 2002,

18% of deaths in the USA were from heart disease, compared with 20% in the UK. The USA lost

8 DALYs per 1000 population to heart disease and a further 4 DALYs per 1000 population to stroke,

and the UK lost 7 DALYs per 1000 population to heart disease and 4 DALYs per 1000 population

to stroke. Afghanistan has the highest rate of DALYs lost to heart disease (36 DALYs per 1000

population), and France, Andorra, Monaco, Japan, Korea, Dominica, and Kiribati have the lowest

(13 DALYs per 1000 population). Mongolia has the highest rate for stroke (25 DALYs per 1000

population lost) and Switzerland the lowest (2 DALYs per 1000 population lost).

AETIOLOGY/

RISK FACTORS

Deaths from CHD are not evenly distributed across the population. They are more common in men

than in women; 67% more common in men from Scotland and the north of England than the south

of England; 58% more common in male manual workers; twice as common in female manual

workers than female non-manual workers; and about 50% higher in South Asian people living in

the UK than in the average UK population. In the UK there are 14% more CHD deaths in the winter

months than in the rest of the year.

[1]

CVD in the UK generally results from the slow build-up of

atherosclerosis over many decades, with or without thrombosis. The long development time of

atherosclerosis means that small changes in lifestyle may have profound effects on risk of CVD

over decades. However, while there is strong evidence from epidemiological studies of the impor-

tance of lifestyle factors such as smoking, physical activity, and diet in the process of devel-

opment of CVD,

[2]

adjusting for confounding can be difficult, and the long timescales involved

make proving the effectiveness of preventive interventions in trials difficult. In practice, risk fac-

tors rather than disease outcomes are often the only practical outcomes for intervention

BMJ Publishing Group Ltd 2007. All rights reserved. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

Primary prevention of CVD: diet and weight loss

B

l

o

o

d

a

n

d

l

y

m

p

h

d

i

s

o

r

d

e

r

s

studies in low-risk people. Such risk factors include blood pressure, body mass index, serum lipids,

and development of diabetes.

PROGNOSIS Improvements in diet and reduction in weight may lower the risk of cardiovascular disease by ex-

erting favourable changes on CVD risk factors (obesity, high blood pressure, elevated serum lipids,

diabetes).

AIMS OF

INTERVENTION

To change lifestyle factors, cardiovascular risk factors, and risk of CVD and death in the general

population (adults without existing serious risk factors such as hypertension, dyslipidaemia, or dia-

betes), with minimum adverse effects.

OUTCOMES Lifestyle change; changes in risk factors such as serum lipids, weight, blood pressure, and glucose

tolerance; cardiovascular events such as myocardial infarction, angina, stroke, and heart failure;

deaths (total or from CVD); adverse effects.

METHODS BMJ Clinical Evidence search and appraisal August 2006. The following databases were used to

identify studies for this review: Medline 1966 to August 2006, Embase 1980 to August 2006, and

The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled

Clinical Trials 2006, Issue 3. Additional searches were carried out using these websites: NHS

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) for Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects

(DARE) and Health Technology Assessment (HTA), Turning Research into Practice (TRIP), and

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Abstracts of the studies retrieved were

assessed independently by two information specialists using pre-determined criteria to identify

relevant studies. Study design criteria for inclusion in this review were: published systematic reviews

and RCTs in any language containing more than 20 individuals of whom more than 90% were fol-

lowed up for a minimum of 12 months. We included open studies. In addition, we use a regular

surveillance protocol to capture harms alerts from organisations such as the US Food and Drug

Administration (FDA) and the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA),

which are added to the reviews as required.

QUESTION What are the effects of interventions in the general population to reduce sodium intake?

OPTION ADVICE TO REDUCE SODIUM INTAKE: EFFECTS ON CVD RISK. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . New

Two systematic reviews found that reducing sodium intake in people without hypertension reduced blood

pressure compared with usual diet. One subsequent RCT of very tight control of dietary sodium in people

with hypertension found that reducing sodium intake (as part of a low-fat and high-fruit-and-vegetable diet)

reduced blood pressure.

Benefits: We found two systematic reviews

[3] [4]

and one subsequent RCT.

[5]

Low-sodium diet for blood pressure:

The first systematic review (search date not reported, 3 RCTs, 2326 adults without hypertension)

found that dietary advice to people without hypertension to reduce their sodium intake compared

with continuing on their usual diet significantly reduced mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure

at 612 months (mean fall in systolic blood pressure: 2.3 mm Hg, 95% CI 1.6 mm Hg to 3.1 mm Hg;

mean fall in diastolic blood pressure: 1.2 mm Hg, 95% CI 0.6 mm Hg to 1.8 mm Hg).

[3]

At 1360

months, effects of low-sodium dietary advice compared with usual diet were smaller (mean fall in

systolic blood pressure: 1.1 mm Hg, 95% CI 0.3 mm Hg to 1.9 mm Hg; mean fall in diastolic blood

pressure: 0.5 mm Hg, 95% CI 0 mm Hg to 1.1 mm Hg). The advice was intensive, more than is

usual in primary care. The second systematic review (search date 1996, 29 RCTs, 2 of which were

in the first review, number of people not reported) compared less-intensive advice to reduce sodium

in people with normal blood pressure at baseline versus no restriction on the length of follow up

required.

[4]

The review did not perform a meta-analysis, but it reported that a reduction in sodium

intake of 100 mmol daily (a reduction of about 60%) would result in reductions of about 1.0 mm Hg

systolic and 0.1 mm Hg diastolic blood pressure. We found one subsequent RCT (412 adults from

the USA with systolic blood pressure of 120159 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure of

8095 mm Hg at baseline, 41% had hypertension [140159 mm Hg systolic or 9095 mm Hg av-

erage in 3 screening visits], mean age 48 years, 56% women, 56% black, 40% non-Hispanic white).

[5]

This RCT is reported here despite its short length of follow up and high number of people with

hypertension as it is unique in providing very tight control of dietary sodium and other constituents

by providing all food consumed for three 1-month periods, and therefore gives good estimates of

actual blood pressure response to specific changes in sodium intake. The RCT compared a diet

rich in fruit, vegetables, and low-fat dairy foods and low in saturated and trans fats (the DASH diet

[Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension]) versus a typical US diet. Within each diet, both groups

BMJ Publishing Group Ltd 2007. All rights reserved. ........................................................... 3

Primary prevention of CVD: diet and weight loss

B

l

o

o

d

a

n

d

l

y

m

p

h

d

i

s

o

r

d

e

r

s

had 1 month periods of either high sodium (142 mmol sodium/day, which is close to the UK daily

mean of 187 mmol in men and 139 mmol in women

[6]

), intermediate (106 mmol/day), or low

(65 mmol/day) sodium. For people without hypertension, those on the US diet had significant de-

creases in systolic and diastolic blood pressure when moving from high to intermediate and from

intermediate to low sodium intakes and those on the DASH diet had smaller decreases in systolic

and diastolic blood pressure when moving from high to intermediate or from intermediate to low

sodium intakes (see table 1, p 15 ). Additionally, being on a DASH diet resulted in consistently

lower blood pressure than being on the standard US diet; a dietary change to a diet high in fruit,

vegetables, and low-fat dairy foods, low in saturated fat resulted in almost the same reduction in

blood pressure as major salt reduction, but was likely to confer additional health benefits (e.g. on

lipid levels). People on the low-sodium DASH diet had the lowest systolic blood pressure of all.

Low-sodium diet for cardiovascular disease and mortality:

One systematic review compared the effect of dietary sodium advice versus usual diet on deaths

and cardiovascular events.

[3]

It reported that there were too few events to draw any conclusions.

Harms: Low-sodium diet for blood pressure:

The first review reported no adverse effects associated with advice to reduce sodium intake.

[3]

The second review

[4]

and subsequent RCT

[5]

gave no information on harms.

Low-sodium diet for cardiovascular disease and mortality:

The review reported no adverse effects associated with advice to reduce sodium intake.

[3]

Comment: None.

OPTION ADVICE TO REDUCE SODIUM INTAKE: EFFECTS ON SODIUM INTAKE. . . . . . . . . . . . . New

One systematic review found that intensive advice to reduce sodium intake decreased sodium intake (mea-

sured by sodium excretion) compared with usual diet.

Benefits: Effect on behaviour:

We found one systematic review (search date 2000, 3 RCTs, 2326 adults without hypertension).

[3]

The review found that advice to reduce sodium intake significantly reduced excreted sodium

compared with usual diet at 1360 months (WMD 34 mmol sodium/24 hours, 95% CI 19 mmol/24

hours to 50 mmol/24 hours). These RCTs were in healthy people, predominantly white, male, and

from the USA, mean age 40 years, with blood pressure just below the definition of hypertension

(mean diastolic blood pressure: 8386 mm Hg; systolic blood pressure: 124127 mm Hg). The

advice in these three RCTs was intensive, and involved regular group and individual counselling

for extended periods, as well as additional support materials such as recipes, lists of sodium contents

of common food brands, shopping expeditions, etc.

Harms: The review reported no adverse effects associated with advice to reduce sodium intake.

[3]

Comment: Trials of dietary advice to reduce sodium in adults without hypertension found that those in the low-

sodium arm had difficulties with their diets including the diets being inconvenient, conflicting

with schedules, needing extra time to plan, and being difficult to stick to when eating out. However,

in one trial, psychological wellbeing scores increased in those on the low-sodium diet compared

with those on their usual diets.

[3]

Clinical guide:

This type of intensive intervention is not realistic in primary care, but we found no systematic review

or RCTs assessing the effect of public health interventions such as reducing the sodium content

of processed foods, although this would seem a sensible way of making it easier for the whole

population to consume less sodium. Under highly controlled conditions, halving dietary sodium has

similar effects in reducing blood pressure as a diet high in fruit, vegetables, low-fat dairy foods,

wholegrain products, nuts, fish, and poultry, and low in saturated fat and sugars, compared with a

usual US diet and the fruit-and-vegetable diet would be expected to have additional beneficial

effects on lipids and other risk markers. There is evidence that a reduction of 20 mm Hg in systolic

blood pressure is associated with halving of the risk of vascular mortality, so a reduction of 1 mm Hg

systolic resulting from intensive dietary interventions to reduce sodium intake in the studies above

would be associated with a reduction in risk of about 2.5%.

[7]

This type of reduction is clinically

important in a population but not in individuals. As the intensive intervention provided in the trials

is relevant to individuals, but not to populations, the results are clinically disappointing. The more

Mediterranean-pattern diet is likely to have similar-sized effects through its blood pressure-lowering

effects, as well as additional benefits in promotion of healthy lipids, body weight, prevention of os-

teoporosis, provision of additional fruit and vegetables, etc, and so may have a greater effect on

prevention of cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases.

BMJ Publishing Group Ltd 2007. All rights reserved. ........................................................... 4

Primary prevention of CVD: diet and weight loss

B

l

o

o

d

a

n

d

l

y

m

p

h

d

i

s

o

r

d

e

r

s

QUESTION What are the effects of a cholesterol-lowering diet in the general population?

OPTION ADVICE TO REDUCE SATURATED FAT INTAKE: EFFECTS ON CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

RISK. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . New

One systematic review found no significant difference in mortality between reducing dietary saturated fat

intake compared with usual care at less than 2 years; however, it did find that reducing dietary saturated fat

intake decreased mortality at 2 years or longer. A second systematic review found no significant difference

in mortality between multiple interventions including reducing dietary saturated fat intake compared with

usual care; however, the people in the RCTs were young, and follow-up was sometimes short.

Benefits: Effect on cardiovascular disease and mortality:

We found two systematic reviews.

[8] [9]

The first systematic review (search date 1999, 27 RCTs,

18,196 adults with and without cardiovascular disease [CVD], 14 RCTs of people with low CVD

risk, 6 RCTs of moderate risk, and 7 RCTs of high risk) compared low saturated fat advice or dietary

support versus usual diet for at least 6 months.

[8]

The review found no significant difference in

total mortality or cardiovascular mortality between advice to reduce dietary fat compared with

usual diet (total mortality: RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.12; cardiovascular mortality: RR 0.84, 95%

CI 0.77 to 1.07). However, the review found that there were significantly fewer cardiovascular

events with advice to reduce dietary fat (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.72 to 0.99). The review found no sig-

nificant difference in cardiovascular events at 2 years or less between low saturated fat advice or

dietary support compared with usual diet, but found that cardiovascular events were significantly

fewer at 2 years or more with advice to reduce fat (2 years or less: RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.23;

2 years or more: RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.65 to 0.90). Subgroup analysis by level of cardiovascular risk

(low risk: general population; medium risk: those with risk factors; high risk: those with existing

CVD) and type of support (dietary advice, dietary advice plus supplements, or diet provided) seemed

to make little difference to the effect size, although those at high risk showed a significant effect

as there were more events in this group (cardiovascular events for those at low cardiovascular

risk: RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.20; high cardiovascular risk: RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.70 to 0.99). The

second systematic review (search date 1995, 14 RCTs with 6 months' follow-up or longer, 1,206,000

person-years of observation in RCTs with risk-factor or clinical-event outcomes, and excluding

those in secondary prevention, or in children or adults under 40 years of age) compared multiple-

risk-factor interventions versus no intervention.

[9]

The review found no significant difference in

reduction in total or coronary heart disease mortality between multiple-risk-factor interventions and

no intervention (total mortality: OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.02; coronary heart disease mortality:

OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.04) over 903,000 person-years of observation, but the people were

generally young (mean age 45.254.1 years) and follow-up was sometimes of short duration (mean

follow up 1.511.8 years).

Harms: The reviews gave no information on adverse effects.

[8] [9]

Comment: None.

OPTION ADVICE TO REDUCE SATURATED FAT INTAKE: EFFECTS ON FAT INTAKE. . . . . . . . . . New

One systematic review found that multiple advice components to reduce saturated fat intake were associated

with more reduction in saturated fat intake compared with simple dietary advice. A second systematic review

found inconclusive evidence on the effects of advice to reduce saturated fat intake compared with no advice.

Four subsequent RCTs found that advice to reduce saturated fat intake was associated with reduced satu-

rated fat intake.

Benefits: We found two systematic reviews

[10] [11]

and four subsequent RCTs.

[12] [13] [14] [15]

The first

systematic review (search date 2001, 17 RCTs, more than 27,795 adults with and without risk

factors for cardiovascular disease [CVD]) compared dietary advice to reduce total or saturated fat

intake for at least 3 months versus usual diet.

[10]

Of the 17 RCTs assessing the effect of dietary

counselling on saturated fat intake, six RCTs found a self-reported large effect size in people's re-

duction in saturated fat intake (as either grams of saturated fat or percentage of calories as satu-

rated fat) (a reduction of more than 3%), five RCTs found a medium effect (1.33.0% reduction),

and six RCTs found a small effect (less than 1.3% reduction). Effect sizes were calculated using

(in order of preference): net difference in change, difference at final follow-up, or relative change.

In this analysis, RCTs that used more intensive interventions achieved greater effect sizes. Those

in primary care settings tended to produce small- or medium-sized effects, mainly because they

used lower-intensity interventions than those in special research clinics. Using more components

(dietary assessment, family involvement, social support, group counselling, food interaction such

as taste testing and cooking, goal setting, and advice appropriate to the patient group) was asso-

ciated with greater effect sizes. The authors of the review reported that baseline level of CVD risk

BMJ Publishing Group Ltd 2007. All rights reserved. ........................................................... 5

Primary prevention of CVD: diet and weight loss

B

l

o

o

d

a

n

d

l

y

m

p

h

d

i

s

o

r

d

e

r

s

did not seem associated with effect size after stratification for intensity of intervention. The second

systematic review (search date 1993) identified eight RCTs, 3 of which were also identified by the

first review

[10]

, assessing diets to reduce dietary fat in primary prevention of free-living adults over

at least 3 months.

[11]

It reported that, at 918 months, only four RCTs noted effects in reported

dietary fat intake, two of which were trials of breast cancer prevention. The review did not perform

a meta-analysis because of heterogeneity between RCTs. Two RCTs found a significant reduction

in dietary fat intake with advice compared with no advice however, these were the two trials of

breast cancer prevention. RCTs included in the review that reported both dietary saturated fat intake

and blood lipids suggested significant effects on dietary fat, but non-significant effects on

lipids suggesting that self-reported saturated fat intake may not be a good indicator of usual intake.

[11]

The first subsequent RCT (235 healthy people aged 3059 years with siblings who were diag-

nosed with coronary heart disease before the age of 60 years) found that nurse counselling signif-

icantly reduced saturated fat intake at 2 years compared with usual care (4.9 g/day with counselling

v +1.9 g/day with usual care; P = 0.0002).

[12]

The second subsequent RCT (545 premenopausal

women, mean age 47 years) found that a 5-year cognitive behavioural programme significantly

reduced saturated fat as a percentage of total calories compared with no programme (9% with

programme v 11% with no programme; P less than 0.05).

[13]

The third subsequent RCT (616

healthy women aged 4070 years) found a significant reduction in total fat as a percentage of en-

ergy in the intervention group compared with control (advice for breast self-examination) at 12

months (35% with counselling v 39% with control; P less than 0.001).

[14]

The fourth subsequent

RCT (143 people with an elevated risk for CVD, mean age 58 years) also found a significant re-

duction in energy from saturated fat 12 months after nutritional counselling by family physicians

compared with no advice (3% with counselling v 1% with no advice; P less than 0.05).

[15]

Harms: The systematic reviews

[10] [11]

and RCTs

[12] [13] [14] [15]

gave no information on adverse effects.

Comment: Once people in a trial have been told to reduce total or saturated fat, they have a tendency to un-

derreport their intake to a greater extent than control groups. There is often inconsistency in effec-

tiveness when trials report both changes in fat intake (which is self reported in a variety of ways)

and serum lipids (which are likely to provide a better view of saturated fat intake over the past few

weeks). Trials often report significant reductions in dietary fats without significant changes in total

or low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

QUESTION What are the effects of interventions to increase or maintain weight loss?

OPTION DIETS AND BEHAVIOURAL INTERVENTIONS: EFFECTS ON WEIGHT LOSS. . . . . . . . . New

Systematic reviews and RCTs found that combinations of interventions (physical, dietary, and behavioural)

reduced body weight compared with usual care. Systematic reviews and RCTs of less complex interventions

found that they were less effective at reducing body weight.

Benefits: Weight-reducing diets, effect on weight:

We found two systematic reviews

[16] [17]

and one subsequent RCT.

[18]

The first systematic review

(search date 2001, 26 RCTs, 3048 people with body mass index [BMI] of 28 kg/m

2

or greater) in-

cluded RCTs that compared weight-reducing diets versus usual diets, where weight was measured

after at least 12 months.

[16]

Thirteen RCTs of low-fat diets compared with usual diet found that

low-fat diets resulted in greater weight loss at 12 months (WMD 5.3 kg, 95% CI 5.9 kg to 4.8 kg),

24 months (WMD 2.4 kg, 95% CI 3.6 kg to 1.2 kg), and 36 months (WMD 3.6 kg, 95% CI

4.5 kg to 2.6 kg), with no significant difference at 60 months (WMD 0.2 kg, 95% CI 2.0 kg to

+1.6 kg).

[16]

Comparisons of low-calorie or very-low-calorie diets versus usual diet were only found

in subgroups of people with chronic illness. RCTs comparing low-calorie diets versus low-fat diets,

very-low-calorie diets versus low-fat diets, and very-low-calorie diets versus low-calorie diets were

found, but studies were small and no significant differences were found at 12 months or later.

[16]

The second systematic review (search date 2003, 29 RCTs) included systematic reviews and RCTs

of screening for obesity, weight-reducing, and weight-maintaining interventions.

[17]

The review

found that weight loss trials most likely to succeed were high intensity (where contact was more

frequent than monthly). The subsequent RCT (160 people) compared four weight-loss diets (Atkins,

Zone, Weight Watchers, and Ornish diets) and found no significant differences in weight loss at 1

year or study completion (at 1 year: 2.1 kg with Atkins v 3.2 kg with Zone v 3.0 kg with Weight

Watchers v 3.3 kg with Ornish; P = 0.4 between groups; at study completion: 52% with Atkins

v 65% with Zone v 65% with Weight Watchers v 50% with Ornish; P = 0.08 between groups).

[18]

Behavioural interventions, effect on weight:

We found one systematic review (search date 2003, 36 RCTs, 3495 overweight or obese people,

BMI greater than 25 kg/m

2

) of psychological interventions for sustained weight loss in overweight

BMJ Publishing Group Ltd 2007. All rights reserved. ........................................................... 6

Primary prevention of CVD: diet and weight loss

B

l

o

o

d

a

n

d

l

y

m

p

h

d

i

s

o

r

d

e

r

s

or obese adults.

[19]

Ten of these RCTs compared a behavioural intervention versus no treatment,

and two reported outcomes later than 12 months, finding that those in the behavioural-intervention

arm lost more weight on average than those in the control arm (2.0 kg, 95% CI 2.7 kg to 1.3 kg).

Comparing more-intensive versus less-intensive behavioural interventions (10 RCTs, 306 people)

found significantly greater weight loss in those on more-intensive interventions in studies of up to

1 year (2.3 kg, 95% CI 3.3 kg to 1.4 kg). One RCT assessed outcomes longer than 1 year and

found no significant difference in weight loss.

[19]

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) added to

diet plus exercise versus diet plus exercise alone (2 RCTs, 63 people) showed significantly more

weight loss with CBT (4.9 kg, 95% CI 7.3 kg to 2.4 kg). Direct comparison of CBT compared

with behavioural interventions found that CBT was associated with significantly more weight loss

(1 RCT, 24 people, difference of 5.7 kg; P less than 0.01).

[19]

We found a second systematic review

asking whether brief interventions using motivational interviewing were effective across several

behavioural domains including diet and exercise (search date 1999, 29 RCTs of which 5 were of

diet plus exercise), and which included RCTs that compared motivational interviewing versus a

control group.

[20]

Using unit-free effect sizes, they suggest that three of the five trials showed

statistically significant benefit. One additional RCT of 92 overweight adults (mean BMI 33.1 kg/m

2

) compared behavioural counselling plus internet-based weight-loss programme versus internet-

based weight-loss programme alone, and found greater weight loss in the behavioural counselling

group at 12 months (4.4 kg with behavioural counselling plus internet-based weight-loss programme

v 2.0 kg with internet-based weight-loss programme alone; P = 0.04).

[21]

Combined interventions, effect on weight:

We found one systematic review (search date 2003), which suggested that successful interventions

were more likely to include two or three strategies (combining behavioural, dietary, and physical

activity intervention).

[17]

One large RCT identified by the review (1191 men and women) comparing

weight loss using dietary, physical, and social support versus usual care found that combined in-

terventions reduced weight by 2.7 kg at 18 months and 2.0 kg at 36 months (no further data report-

ed).

[22]

We also found three subsequent RCTs.

[23] [24] [25]

The first subsequent RCT (423

overweight and obese adults) identified by the review compared the effect of participation in the

Weight Watchers commercial programme of group-based dietary, physical activity, and behavioural

change with two 20-minute nutritionist interviews and self-help materials. It found that those ran-

domised to the commercial programme had lost more weight at 2 years (2.7 kg; P less than 0.001),

and had greater decreases in waist circumference and BMI.

[23]

The second subsequent RCT (44

obese sedentary postmenopausal women) added self-control skills training to a comprehensive

programme of lifestyle, exercise, attitudes, relationships, and nutrition.

[24]

The RCT found that

self-control skills plus comprehensive programme significantly reduced weight compared with

comprehensive programme (6.5%; no further data reported). The third subsequent RCT (110

obese men with erectile dysfunction) found that detailed advice on diet and physical activity (com-

pared with general advice to the control group) resulted in significant reductions in BMI in the inter-

vention compared with the control group, after 2 years (no further data reported).

[25]

Physical activity plus weight-reducing diets versus weight-reducing diets alone, effect on

weight:

One systematic review compared weight-reducing diets plus exercise versus weight-reducing diets

alone in adults with obesity (search date 2001).

[26]

The review found that adding exercise to diet

significantly increased mean weight loss (at 12 months: 1.95 kg, 95% CI 3.22 kg to 0.68 kg; at

36 months: 8.22 kg, 95% CI 15.27 kg to 1.16 kg).

Behavioural therapy plus weight-reducing diets with or without physical activity versus

weight-reducing diets with or without physical activity, effect on weight:

One systematic review found that adding behavioural therapy to weight-reducing diet significantly

improved weight loss at 12 months, but found no significant difference at later time points (4 RCTs;

at 12 months: 7.7 kg, 95% CI 12.0 kg to 3.4 kg; at 36 months: +2.9 kg, 95% CI 2.8 kg to

+8.6 kg; at 60 months: 1.9 kg, 95% CI 7.6 kg to +3.8 kg).

[26]

However, in one cluster RCT, ad-

dition of behavioural therapy to weight-reducing diets plus exercise did not improve weight loss at

12 months compared with weight-reducing diets plus exercise, and addition of exercise and be-

havioural therapy to diet did not significantly improve weight loss at 12 months. A second system-

atic review found that adding behavioural therapy to diet plus exercise (compared with diet plus

exercise alone) produced a heterogeneous result, but that five of the six studies favoured the addition

of behavioural therapy (the sixth favoured diet plus exercise alone).

[19]

Harms: Adverse effects were addressed in few reviews or trials. One review found that adverse effects

(such as illnesses and deaths) occurred in both arms, but, as such events were rare, patterns were

not clear.

[26]

One subsequent RCT reported that it did not identify any serious adverse effects of

the diets.

[18]

BMJ Publishing Group Ltd 2007. All rights reserved. ........................................................... 7

Primary prevention of CVD: diet and weight loss

B

l

o

o

d

a

n

d

l

y

m

p

h

d

i

s

o

r

d

e

r

s

Comment: The main methodological issue in weight-reducing trials is the high level of withdrawals, particularly

in the longer trials, which can provide more useful information. People who completed trials tended

to do better, and differential withdrawal rates can misrepresent the effectiveness of interventions.

Potential adverse effects that should be assessed in trials and reviews include eating disorders

such as anorexia or bulimia (which might be precipitated by a concentration on body image, food,

and exercise) and rebound binge eating (which might lead to increased weight, but would tend to

occur in those who have withdrawn from the study).

OPTION LIFESTYLE INTERVENTIONS: EFFECTS ON MAINTAINANCE OF WEIGHT LOSS. . . . . New

One systematic review found that weight-maintenance strategies can maintain weight loss; however, the

review reported few details of how the conclusion was reached. RCTs found inconclusive evidence on the

effects of different lifestyle interventions (physical, dietary, and behavioural) to maintain weight loss.

Benefits: Effects on weight:

We found one systematic review (search date 2003, 29 RCTs, included systematic reviews and

RCTs of screening for obesity, weight-reducing and weight-maintaining interventions).

[17]

It found

that maintenance strategies helped to maintain weight loss (mentioning 2 trials) but provided few

details of how this conclusion was reached. We found six RCTs of weight-maintenance programmes

of at least 1 year after a weight-loss programme.

[27] [28] [29] [30] [31] [32]

The first RCT (82 obese

men, mean body mass index [BMI] 32.9 kg/m

2

, mean weight 106.0 kg, who had a very-low-energy

diet for 2 months, mean body weight after the diet 91.7 kg) found no significant difference in mean

body weight at 31 months between walking (45 minutes 3 times weekly for 6 months), resistance

training (45 minutes 3 times weekly for 6 months), and no exercise (102.0 kg with walking v 99.9 kg

with resistance training v 100.7 kg with no exercise; P = 0.8 between groups).

[27]

The second RCT

(82 obese premenopausal women, mean BMI 34.0 kg/m

2

, mean weight 92.0 kg, who had a very-

low-energy diet for 3 months, mean weight loss after the diet 13.1 kg) found no significant difference

in mean body weight between diet counselling plus a walking programme (to expend 4.2 MJ/week),

diet counselling plus a more intensive walking programme (to expend 8.4 MJ/week), and diet

counselling alone (83.9 kg with lower walking programme v 87.4 kg with higher walking programme

v 89.7 kg with no walking; P = 0.07 between groups).

[28]

The third RCT (80 obese women whose

mean weight loss was 8.74 kg in an initial 20-week behavioural treatment programme, who then

had either: problem-solving therapy, relapse prevention training, or no further treatment for 12

months) found that women who had subsequent problem-solving therapy lost significantly more

body weight than women who had no further treatment (10.8 kg with problem-solving therapy v

4.1 kg with no treatment; P = 0.019).

[29]

The RCT found no significant difference between any

other comparison (P values not reported). The fourth RCT (128 African-American people, mean

BMI 37.5 kg/m

2

who had a 10-week healthy eating and lifestyle programme, mean weight loss

1.5 kg, mean BMI after the programme 37.0 kg/m

2

) found no significant difference at 820 months

in change of body weight from baseline between people who had either further group counselling,

staff-facilitated self help, or clinic visits only (0.8 kg with group counselling v 1.3 kg with self help

v 1.4 kg with clinic visits; P = 0.90 between treatments).

[30]

The fifth RCT (255 people, mean BMI

31.8 kg/m

2

, mean body weight 89.4 kg, who had a 6-month weight control programme by interactive

television, mean weight loss 7.8 kg) found no significant difference in overall weight loss at the end

of a 12-month maintenance period between three maintenance strategies: frequent therapist contact,

minimum therapist contact, and internet therapist support (5.1 kg with frequent therapist contact v

5.5 kg with minimum therapist contact v 7.6 kg with internet therapist support; P = 0.23).

[31]

The

sixth RCT (67 people who had a 6-month weight-loss programme, mean weight loss 8.8 kg, mean

BMI after the programme 30.8 kg/m

2

, mean body weight 85.2 kg, mean weight and BMI before

programme not reported) found that people completing a weight-focused maintenance programme

gained significantly less weight pver 12 months than people on an exercise-focused maintenance

programme (+0.8 kg with weight-focused maintenance programme v +4.4 kg with exercise-focused

maintenance programme; P less than 0.01).

[32]

Harms: The systematic review

[17]

and subsequent RCTs

[27] [28] [29] [30] [31] [32]

gave no information

on adverse effects.

Comment: None.

OPTION LIFESTYLE INTERVENTIONS: EFFECTS ON PREVENTING WEIGHT GAIN. . . . . . . . . . New

One systematic review and two RCTs found inconclusive evidence on the effects of lifestyle interventions

to prevent weight gain.

BMJ Publishing Group Ltd 2007. All rights reserved. ........................................................... 8

Primary prevention of CVD: diet and weight loss

B

l

o

o

d

a

n

d

l

y

m

p

h

d

i

s

o

r

d

e

r

s

Benefits: Effects on weight:

We found one systematic review,

[33]

one additional RCT,

[34]

and one subsequent RCT.

[35]

The

systematic review (search date not reported, 5 studies [4 controlled and 1 uncontrolled], number

of people not reported) assessed community interventions promoting physical activity for preventing

weight gain.

[33]

It found no significant effects of the intervention on weight gain. The additional

RCT compared education (by newsletters) versus education plus incentives versus no education

to prevent weight gain.

[34]

It found no significant difference in a between-group comparison in

weight gain at 3 years (+1.6 kg with education v +1.5 kg with education plus incentives v +1.8 kg

with no education; P = 0.80). The subsequent RCT compared a dietary and physical advice pro-

gramme with no programme (assessment only) (535 premenopausal women, aged 4450 years).

[35]

It found that weight gain was significantly greater with the advice programme than with no

programme (0.1 kg with advice v +2.4 kg with no advice; reported as significant; P value not re-

ported). It also found that body mass index increase was significantly less with the advice programme

than with no programme (+0.05 kg/m

2

with advice v +0.96 kg/m

2

with no advice; P less than 0.001).

Harms: The review

[33]

and additional RCT

[34]

gave no information on adverse effects. The subsequent

RCT found no signs of increased stress, depressive symptoms, or eating restraint among people

in the intervention group.

[35]

Comment: None.

OPTION TRAINING HEALTH PROFESSIONALS IN PROMOTING WEIGHT LOSS: EFFECTS ON WEIGHT

LOSS. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . New

One systematic review and one subsequent RCT found inconclusive evidence on the effects of training

health professionals for promoting weight loss.

Benefits: Organisational and educational interventions with healthcare staff, effect on weight (of pa-

tients):

We found one systematic review

[36]

and two subsequent RCTs.

[37] [38]

The systematic review

(search date 2000; 5 RCTs, 1 controlled before and after study, 2992 overweight or obese people)

compared interventions to improve health professionals' management of weight versus no interven-

tions.

[36]

It did not perform a meta-analysis, as some of the studies were small and of low quality;

however, the review authors suggested that reminder systems, brief training interventions, shared

care, inpatient care, and dietician-led treatments may be effective in improving management of

weight. The first subsequent RCT cluster compared obesity management training versus no training

in 44 general practices.

[37]

The RCT found no significant difference in weight change in obese

people in the practices with training than with no training at 12 months (843 obese people; +1 kg,

95% CI 1.9 kg to +3.9 kg; P = 0.5). The second subsequent RCT compared dietician counselling,

dietician counselling plus doctor counselling, and no counselling.

[38]

It found that dietician coun-

selling resulted in significantly more weight loss than no counselling (6.6%, 95% CI 7.6% to

5.8%), and that dietician plus doctor counselling resulted in significantly more weight loss than

no counselling (7.3%, 95% CI 8.3% to 6.5%). There was no significant difference in weight loss

between doctor plus dietician counselling and dietician only counselling (+0.7%, 95% CI 0.42%

to +1.82%).

Harms: The review

[36]

and RCTs

[37] [38]

gave no information on adverse effects.

Comment: None.

OPTION DIETS AND BEHAVIOURAL INTERVENTIONS: EFFECTS ON CVD RISK. . . . . . . . . . . . . New

We found no systematic review or RCTs assessing the effects of diets and behavioural intervention in reducing

cardiovascular risk in the general population.

Benefits: Effects on cardiovascular risk:

We found no systematic review or RCTs.

Harms: We found no RCTs.

Comment: None.

BMJ Publishing Group Ltd 2007. All rights reserved. ........................................................... 9

Primary prevention of CVD: diet and weight loss

B

l

o

o

d

a

n

d

l

y

m

p

h

d

i

s

o

r

d

e

r

s

QUESTION What are the effects on reducing CVD risk in the general population of eating more fruit and

vegetables?

OPTION INCREASING FRUIT AND VEGETABLE INTAKE: EFFECTS ON CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

RISK. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . New

Two systematic reviews of cohort studies found that increasing fruit and vegetable intake decreased cardio-

vascular risk.

Benefits: Effect on cardiovascular disease risk:

We found no systematic review of RCTs but found two systematic reviews of cohort studies.

[39]

[40]

The first systematic review (search date 2002, 8 cohort studies assessing the effects of fruit

and vegetable consumption on CVD, total number of people not reported) reported that seven of

the eight cohort studies found that a higher intake of fruit and vegetables decreased CVD risk

compared with low intake suggesting protection with higher intakes (no further data reported;

results presented graphically).

[39]

The second systematic review (search date not reported, 11

cohort studies on the effect of fruit and vegetable intake on deaths from ischaemic heart disease)

found that most markers of fruit and vegetable intake (including dietary carotenoids, vitamin C, fruit

fibre, and vegetable fibre) decreased ischaemic heart disease. Total fruit intake and total vegetable

intake also decreased ischaemic heart disease, but less so.

Harms: The reviews gave no information on adverse effects.

[39] [40]

Comment: One earlier systematic review (search date 1995, ecological, case control and cohort studies as-

sessing the relationship between fruit and vegetable intake and CVD; number of people not reported)

found that six of 16 cohort studies suggested a statistically significant effect.

[41]

OPTION BEHAVIOURAL AND COUNSELLING INTERVENTIONS: EFFECTS ON FRUIT AND VEGETABLE

INTAKE. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . New

One systematic review found no significant difference in increase in fruit and vegetable intake between advice

to increase fruit and vegetable intake and usual diet. One subsequent RCT found inconclusive evidence on

counselling to increase fruit and vegetable intake. A second subsequent RCT found that computer-assisted

intervention to increase fruit and vegetable intake in healthy women increased intake compared with a

control of counselling on breast self-examination.

Benefits: We found two systematic reviews

[10] [42]

and one subsequent RCT

[14]

of dietary interventions to

increase the quantity of fruit and vegetables eaten. The first systematic review (search date not

reported, included 12 controlled trials [unclear if they were RCTs], number of people not reported)

assessed the effect of behavioural interventions to increase fruit and vegetable intake compared

with control or usual diet.

[42]

It found no significant difference in the median difference in deltas

of increase in quantity of fruit and vegetables eaten (+16.6, range 3.7 to +60.9). The second

systematic review (search date 2001, 10 RCTs of counselling to increase fruit and vegetable intake

compared with no counselling; 1 of the RCTs was included in the first systematic review;

[42]

number of people not recorded) found that three RCTs produced small or no increases in fruit and

vegetables (less than 0.3 servings/day), five RCTs found medium increases (0.30.8 servings/day),

and two RCTs found large effects (1.43.2 servings/day; no further data reported).

[10]

One subse-

quent RCT (616 healthy women) found that a brief computer-assisted intervention to reduce dietary

fat and increase fruit and vegetable consumption compared with a control intervention (counselling

on breast self-examination) resulted in significantly higher self-reported intake of fruit and vegetable

servings with computer intervention at 12 months compared with control intervention (4.33 serv-

ings/day with computer intervention v 3.40 servings/day with control intervention; P less than 0.001).

[14]

Harms: The systematic reviews

[10] [42]

and subsequent RCT

[14]

gave no information on harms.

Comment: None.

QUESTION What are the effects on reducing CVD risk of antioxidants in the general population?

OPTION HIGH-DOSE ANTIOXIDANT SUPPLEMENTS: EFFECTS ON CARDIOVASCULAR RISK. . New

Systematic reviews found that high-dose supplements of vitamin E and beta carotene did not reduce mor-

tality or cardiovascular events.

BMJ Publishing Group Ltd 2007. All rights reserved. .......................................................... 10

Primary prevention of CVD: diet and weight loss

B

l

o

o

d

a

n

d

l

y

m

p

h

d

i

s

o

r

d

e

r

s

Benefits: Vitamin E:

We found four systematic reviews

[43] [44] [45] [46]

and one subsequent RCT

[47]

on the effects of

vitamin E on cardiovascular disease (CVD) and mortality. The first review (search date 2004, in-

cluding 9 RCTs that tested vitamin E alone, and 10 that tested vitamin E in combination with other

vitamins and minerals) compared vitamin E versus placebo or control in non-pregnant adults over

at least 1 year.

[43]

This review aimed to assess any doseresponse relationship between vitamin

E supplementation and total mortality. Some studies included those with, or at high risk of, CVD,

but most did not. The review found that, overall, there was no effect of vitamin E on total mortality

(RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.04). Doseresponse analysis suggested that all-cause mortality in-

creased with dose, and high-dose vitamin E (400 IU/day or more) significantly increased deaths

(risk difference: 39/10,000 people, 95% CI 3/10,000 people to 74/10,000 people). However, RCTs

using high doses tended to be small and to include people with chronic disease. The second review

(search date 2002, 84 RCTs of vitamin E on CVD, risk factors, or death) found no evidence to

recommend vitamin E alone or in combination for the primary prevention of CVD).

[44]

The primary

prevention RCTs were not pooled. One of two primary prevention RCTs showed a significant re-

duction in total mortality in a trial of vitamin E plus beta carotene plus selenium in rural China

(mainly owing to reductions in cancer mortality). Neither (of two) primary prevention trials of vitamin

E with other vitamins showed any effect of vitamin E on total, fatal, or non-fatal myocardial infarction.

There is a suggestion of statistically (but not clinically) significant reductions in total and low-density

lipoprotein cholesterol levels in those taking vitamin E in primary prevention studies, but units,

confidence intervals, and P values were not reported. The third review (search date 2001, 8 RCTs,

104 512 people) analysed the effects of vitamin E, beta carotene, and ascorbic acid for primary

prevention.

[45]

The review found no significant in CVD at 312 years difference between vitamin

E compared with no antioxidant supplement (4 RCTs, 48 346 people: OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.88 to

1.04). The fourth review (search date not reported, 7 RCTs, 106 615 people [including secondary

prevention]) found no significant difference in cardiovascular events between high-dose vitamin E

(30800 mg/day) compared with no vitamin E (any event: OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.03; non-fatal

myocardial infarction: OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.09; non-fatal stroke: OR 1.03, 95% CI 0.93 to

1.14; cardiovascular death: 1.00, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.05).

[46]

One subsequent RCT (39,876 healthy

women in the USA) compared vitamin E (600 IU on alternate days) versus placebo for 10 years.

[47]

The RCT found no significant difference in myocardial infarction, stroke, or total mortality between

vitamin E compared with placebo (myocardial infarction: RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.23; stroke: RR

0.98, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.17; total mortality: RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.16). However, the RCT did

find significantly fewer cardiovascular deaths with vitamin E compared with placebo (RR 0.76, 95%

CI 0.59 to 0.98).

Beta carotene:

One systematic review (search date 2001, 8 RCTs, 104,512 people) analysed the effects of vitamin

E, beta carotene, and ascorbic acid for primary prevention.

[45]

The review found no significant

difference in CVD at 312 years between beta carotene and no antioxidant supplement (6 RCTs,

85 056 people: OR 1.02, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.08). A second systematic review (search date not report-

ed, 8 RCTs, 138,113 people with and without CVD)

[48]

found that beta carotene 1550 mg daily

significantly increased all-cause mortality at 1.412.0 years compared with placebo (OR 1.07, 95%

CI 1.02 to 1.11). However, the data for both primary and secondary prevention RCTs were pooled,

and no separate meta-analysis for primary prevention RCTs was reported.

Combination of antioxidants:

One RCT compared a combination of antioxidants (ascorbic acid 120 mg plus vitamin E 30 mg

plus beta carotene 6 mg plus selenium 100 g plus zinc 20 mg) versus placebo for 7.5 years.

[49]

The RCT found no significant difference in CVD events or total mortality at 7.5 years (13,017 healthy

middle-aged people in France; CVD: RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.20; total mortality: RR 0.77, 95%

CI 0.57 to 1.00). However, subgroup analysis by sex found significantly less mortality in men, but

found no significant difference in women (men: RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.93; women: RR 1.03,

95% CI 0.64 to 1.63).

Harms: One review reported that there were serious adverse cardiovascular effects with vitamin E in one

RCT, and increased risk of intracerebral haemorrhage with beta carotene (data not reported).

[45]

The review also reported that, in two RCTs, risk of lung cancer was increased with beta carotene

in cigarette smokers. One subsequent RCT found significantly more epistaxis with vitamin E com-

pared with placebo (RR 1.06, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.11).

[47]

Four systematic reviews

[43] [44] [46] [48]

and one RCT

[49]

did not report on adverse effects.

Comment: None.

BMJ Publishing Group Ltd 2007. All rights reserved. .......................................................... 11

Primary prevention of CVD: diet and weight loss

B

l

o

o

d

a

n

d

l

y

m

p

h

d

i

s

o

r

d

e

r

s

QUESTION What are the effects on reduction of CVD risk of omega 3 fatty acids in the general popula-

tion?

OPTION OMEGA 3 FATTY ACIDS: EFFECTS ON CARDIOVASCULAR RISK. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . New

One systematic review found no significant difference between omega 3 supplementation or advice to increase

omega 3 intake compared with placebo in mortality.

Benefits: We found one systematic review (search date 2002, 48 RCTs, 36 913 people), which compared

high-dose omega 3 supplementation or dietary advice for at least 6 months versus control or

placebo.

[50]

If found no significant difference in mortality between omega 3 supplements or advice

compared with placebo or no advice (44 RCTs, 36,195 people; RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.03; in-

cluding 1 RCT of people at high and low risk of cardiovascular disease [CVD], and including RCTs

of fish- and plant-based omega 3 fatty acids). There was also no significant difference for the same

comparison in people with a low risk of CVD (17 RCTs, 14,599 people; RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.70 to

1.64). There was no significant difference for the same comparisons in RCTs with a low risk of

bias, but any risk of CVD (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.36). There was no significant difference in

mortality in subgroup analyses of RCTs of advice to eat more oily fish compared with no advice,

or fish oil capsules compared with placebo (advice: RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.44; capsules: RR

0.90, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.07).

Harms: We found no evidence of increase in cancers with increased omega 3 intake, but estimates were

imprecise and a clinically important effect could not be excluded. Trials reported fewer than 400

cancers (mainly cancer deaths) overall and suggested no effect of omega 3 fatty acids on cancer

(10 RCTs, cancer death or diagnoses: 391/17,433 [2%]; RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.30). The review

of cohort studies found no increase in cancers in those taking greater quantities of omega 3 fatty

acids (10 cohort studies, number of people not reported; RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.19).

[50]

Comment: Clinical guide:

Lack of protective effects of high doses of omega 3 fatty acids in the general public does not mean

that oily fish at more usual dietary levels are not healthy. General population advice in the UK is

that people should eat two portions of fish a week, one of which should be oily.

[51]

The UK Com-

mittee on Toxicity, which reviewed the effects of oily fish and their contaminants with the Scientific

Advisory Committee on Nutrition, set safe upper limits for intake of oily fish on the basis of a wide

review of the evidence.

[51]

QUESTION What are the effects on reduction of CVD risk of a Mediterranean diet in the general popula-

tion?

OPTION MEDITERRANEAN DIET: EFFECTS ON CARDIOVASCULAR RISK. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . New

We found insufficient evidence on the effects of Mediterranean diet on risk factors for cardiovascular disease,

cardiovascular events, or deaths in the general population.

Benefits: We found no systematic review or RCTs on the effects of Mediterranean diet on risk factors for

cardiovascular disease, cardiovascular events, or deaths in the general population. We found one

systematic review (search date not reported; 1 prospective cohort study, 22,034 middle-aged and

older adults in Greece).

[52]

It found that, with a 2/9 increment in Mediterranean diet score (not

described), there was a 25% reduction in total mortality and 33% reduction in heart disease mor-

tality (after adjustment for sex, smoking, education, body mass index, or physical activity) in people

over 55 years old only (no further data reported).

Harms: The non-systematic review gave no information on adverse effects.

[52]

Comment: Clinical guide:

The Mediterranean diet is a pattern of eating characterised by use of olive oil for cooking and little

use of dairy fats. Other characteristics of this diet include increased intake of oily fish, fruit, vegeta-

bles, nuts, pulses (and occasionally low-fat dairy products and red wine), and a lower intake of

processed foods, meat, meat products, and hard fats, compared with a typical European or US

diet.

GLOSSARY

Atkins diet Strictly limits carbohydrate intake while allowing free intakes of protein and fat.

Body mass index (BMI) Calculated by weight (in kilograms) divided by height (in metres) squared.

BMJ Publishing Group Ltd 2007. All rights reserved. .......................................................... 12

Primary prevention of CVD: diet and weight loss

B

l

o

o

d

a

n

d

l

y

m

p

h

d

i

s

o

r

d

e

r

s

Ornish diet Strict diet limiting cholesterol and saturated fat (prohibiting meat), sugars, and alcohol, while promoting

complex carbohydrates. Aims at 10% of energy from fat, 20% from protein, and 70% from carbohydrates.

Weight Watchers diet Group-based restriction of portion sizes and calories based on an exchange system.

Zone diet Aims at 40% of energy from carbohydrates, 30% from protein, 30% from fat from all meals and snacks.

SUBSTANTIVE CHANGES

New option added Advice to reduce sodium intake: effects on CVD risk.

New option added Advice to reduce sodium intake: effects on sodium intake.

New option added Advice to reduce saturated fat intake: effects on cardiovascular disease risk.

New option added Advice to reduce saturated fat intake: effects on fat intake.

New option added Diets and behavioural interventions: effects on weight loss.

New option added Lifestyle interventions: effects on maintainance of weight loss.

New option added Lifestyle interventions: effects on preventing weight gain.

New option added Training health professionals in promoting weight loss: effects on weight loss.

New option added Diets and behavioural interventions: effects on CVD risk.

New option added Increasing fruit and vegetable intake: effects on cardiovascular disease risk.

New option added Behavioural and counselling interventions: effects on fruit and vegetable intake.

New option added High-dose antioxidant supplements: effects on cardiovascular risk.

New option added Omega 3 fatty acids: effects on cardiovascular risk.

New option added Mediterranean diet: effects on cardiovascular risk.

REFERENCES

1. British Heart Foundation. British Heart Foundation Statistics Website. Available

online at: http://www.heartstats.org/ (last accessed 17 July 2007).

2. World Health Organization. The atlas of heart disease and stroke. Geneva: The

World Health Organization, 2004. Available online at: http://www.who.int/cardio-

vascular_diseases/resources/atlas/en/index.html (last accessed 17 July 2007).

3. Hooper L, Bartlett C, Davey Smith G, et al. Advice to reduce dietary salt for pre-

vention of cardiovascular disease. In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 3, 2006.

Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Search date 2000.

4. Fodor JG, Whitmore B, Leenen F, et al. Lifestyle modifications to prevent and

control hypertension. 5. Recommendations on dietary salt. Canadian Hypertension

Society, Canadian Coalition for High Blood Pressure Prevention and Control,

Laboratory Centre for Disease Control at Health Canada, Heart and Stroke

Foundation of Canada. CMAJ 1999;160:S29S34. Search date 1996.[PubMed]

5. Sacks FM, Svetkey LP, Vollmer WM, et al. Effects on blood pressure of reduced

dietary sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet.

New Engl J Med 2001;344:310.[PubMed]

6. Henderson L, Irving K, Gregory J, et al. The National Diet and Nutrition Survey:

adults aged 19 to 64 years. Vitamin and mineral intake and urinary analysis.

Newport: HMSO, 2003.

7. Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, et al. Age-specific relevance of usual blood

pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million

adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet 2002;360:19031913. [PubMed]

8. Hooper L, Summerbell CD, Higgins JP, et al. Reduced or modified dietary fat for

prevention of cardiovascular disease. In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 3, 2006.

Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Search date 1999.

9. Ebrahim S, Smith GD. Systematic review of randomised controlled trials of mul-

tiple risk factor interventions for preventing coronary heart disease. BMJ

1997;314:16661674.[PubMed]

10. Pignone MP, Ammerman A, Fernandez L, et al. Counseling to promote a healthy

diet in adults: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task

Force. Am J Prev Med 2003;24:7592. [PubMed]

11. Brunner E, White I, Thorogood M, et al. Can dietary interventions change diet

and cardiovascular risk factors? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

Am J Public Health 1997;87:14151422. Search date 1993.[PubMed]

12. Moy TF, Yanek LR, Raqueno JV, et al. Dietary counseling for high blood

cholesterol in families at risk of coronary disease. Prev Cardiol

2001;4:158164.[PubMed]

13. Kuller LH, Simkin-Silverman LR, Wing RR, et al. Women's Healthy Lifestyle

Project. A randomized clinical trial: results at 54 months. Circulation

2001;103:3237.[PubMed]

14. Stevens VJ, Glasgow RE, Toobert DJ, et al. One-year results from a brief, com-

puter-assisted intervention to decrease consumption of fat and increase consump-

tion of fruits and vegetables. Prev Med 2003;36:594600.[PubMed]

15. van der Veen J, Bakx C, Van den Hoogen HV, et al. Stage-matched nutrition

guidance for patients at elevated risk for cardiovascular disease: a randomized

intervention study in family practice. J Fam Pract 2002;51:751758.[PubMed]

16. Avenell A, Brown TJ, McGee MA, et al. What are the long-term benefits of weight

reducing diets in adults? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J

Hum Nutr Diet 2004;17:317335. [PubMed]

17. McTigue KM, Harris R, Hemphill B, et al. Screening and interventions for obesity

in adults: summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

Ann Intern Med 2003;139:933949. [PubMed]

18. Dansinger ML, Gleason JA, Griffith JL, et al. Comparison of the Atkins, Ornish,

Weight Watchers, and Zone diets for weight loss and heart disease risk reduction:

a randomized trial. JAMA 2005;293:4353.[PubMed]

19. Shaw K, O'Rourke P, Del Mar C, et al. Psychological interventions for overweight

or obesity. In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 3, 2006. Chichester, UK: John Wiley

& Sons, Ltd. Search date 2003.

20. Dunn C, Deroo L, Rivara FP. The use of brief interventions adapted from motiva-

tional interviewing across behavioral domains: a systematic review. Addiction

2001;96:17251742.[PubMed]

21. Tate DF, Jackvony EH, Wing RR. Effects of Internet behavioral counseling on

weight loss in adults at risk for type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. JAMA

2003;289:18331836.[PubMed]

22. Stevens VJ, Obarzanek E, Cook NR, et al. Long-term weight loss and changes

in blood pressure: results of the Trials of Hypertension Prevention, phase II. Ann

Intern Med 2001;134:111.

23. Heshka S, Anderson JW, Atkinson RL, et al. Weight loss with self-help compared

with a structured commercial program: a randomized trial. JAMA

2003;289:17921798.[PubMed]

24. Carels RA, Darby LA, Cacciapaglia HM, et al. Reducing cardiovascular risk factors

in postmenopausal women through a lifestyle change intervention. J Womens

Health 2004;13:412426.

25. Esposito K, Giugliano F, Di Palo C, et al. Effect of lifestyle changes on erectile

dysfunction in obese men: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA

2004;291:29782984.[PubMed]

26. Avenell A, Brown TJ, McGee MA, et al. What interventions should we add to

weight reducing diets in adults with obesity? A systematic review of randomized

controlled trials of adding drug therapy, exercise, behaviour therapy or combina-

tions of these interventions. J Hum Nutr Diet 2004;17:293316. [PubMed]

27. Borg P, Kukkonen-Harjula K, Fogelholm M, et al. Effects of walking or resistance

training on weight loss maintenance in obese, middle-aged men: a randomized

trial. Int J Obes Relat Metab Dis 2002;26:676683.

28. Fogelholm M, Kukkonen-Harjula K, Nenonen A, et al. Effects of walking training

on weight maintenance after a very-low-energy diet in premenopausal obese

women: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med

2000;160:21772184.[PubMed]

29. Perri MG, Nezu AM, McKelvey WF, et al. Relapse prevention training and prob-

lem-solving therapy in the long-term management of obesity. J Consult Clin

Psychol 2001;69:722726.[PubMed]

30. Kumanyika SK, Shults J, Fassbender J, et al. Outpatient weight management in

African-Americans: the Healthy Eating and Lifestyle Program (HELP) study. Prev

Med 2005;41:488502.[PubMed]

31. Harvey-Berino J, Pintauro S, Buzzell P, et al. Effect of internet support on the

long-term maintenance of weight loss. Obes Res 2004;12:320329.[PubMed]

32. Leermakers EA, Perri MG, Shigaki CL, et al. Effects of exercise-focused versus

weight-focused maintenance programs on the management of obesity. Addict

Behav 1999;24:219227.[PubMed]

33. Fogelholm M, Lahti-Koski M. Community health-promotion interventions with

physical activity: does this approach prevent obesity? Scand J Nutr

2002;46:173177.

34. Jeffery RW, French SA. Preventing weight gain in adults: the pound of prevention

study. Am J Public Health 1999;89:747751.[PubMed]

35. Simkin-Silverman LR, Wing RR, Boraz MA, et al. Lifestyle intervention can prevent

weight gain during menopause: results from a 5-year randomized clinical trial.

Ann Behav Med 2003;26:212220.[PubMed]

36. Harvey EL, Glenny AM, Kirk SF, et al. Improving health professionals' manage-

ment and the organisation of care for overweight and obese people. In: The

Cochrane Library, Issue 3, 2006. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Search

date 2000.

37. Moore H, Summerbell CD, Greenwood DC, et al. Improving management of

obesity in primary care: cluster randomised trial. BMJ

2003;327:10851088.[PubMed]

38. Pritchard DA, Hyndman J, Taba F. Nutritional counselling in general practice: a

cost effective analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health 1999;53:311316.[PubMed]

39. Hu FB, Willett WC. Optimal diets for prevention of coronary heart disease. JAMA