Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Nonallergic Rhinitis, With A Focus On Vasomotor Rhinitis

Загружено:

Raga Manduaru0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

47 просмотров6 страницaaahhdhd

Оригинальное название

Nonallergic Rhinitis, With a Focus on Vasomotor Rhinitis

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документaaahhdhd

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

47 просмотров6 страницNonallergic Rhinitis, With A Focus On Vasomotor Rhinitis

Загружено:

Raga Manduaruaaahhdhd

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 6

Nonallergic Rhinitis, With a Focus on Vasomotor Rhinitis

Clinical Importance, Differential Diagnosis, and Effective

Treatment Recommendations

Mark D. Scarupa and Michael A. Kaliner

Abstract: The term Brhinitis[ denotes nasal inammation causing a

combination of rhinorrhea, sneezing, congestion, nasal itch, and/or

postnasal drainage. Allergic rhinitis is the most prevalent and most

frequently recognized form of rhinitis. However, nonallergic rhinitis

(NAR) is also very common, affecting millions of people. By con-

trast, NAR is less well understood and less often diagnosed. Nonaller-

gic rhinitis includes a heterogeneous group of conditions, involving

various triggers and distinct pathophysiologies. Nonallergic vasomo-

tor rhinitis is the most common form of NAR and will be the primary

focus of this review. Understanding and recognizing the presence of

NAR in a patient is essential for the correct selection of medications

and for successful treatment outcomes.

Key Words: nonallergic rhinitis, vasomotor rhinitis,

mixed rhinitis, allergic rhinitis

(WAO Journal 2009; 2:20Y25)

N

onallergic rhinitis (NAR) is not a single disease with 1

underlying mechanism but is instead a collection of mul-

tiple distinct conditions that cause similar nasal symptoms.

Nonallergic rhinitis is at times almost indistinguishable from

allergic rhinitis (AR), although typically nasal and palatal itch,

sneezing, and conjunctival irritation are less prominent. Non-

allergic rhinitis can and frequently does exist simultaneously

with AR, a condition known as Bmixed rhinitis.[ The most clini-

cally prevalent form of NAR is vasomotor or idiopathic rhinitis,

characterized by sporadic or persistent perennial nasal symp-

toms that are triggered by environmental conditions, such as

strong smells; cold air; changes in temperature, humidity, and

barometric pressure; strong emotions; ingesting alcoholic bev-

erages; and changes in hormone levels. These triggers do not

involve immunoglobulin E cross-linking or histamine release.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND IMPACT

The incidence of NAR varies from study to study.

Almost all publications on NAR are found in North American

and European literature. Thus, it is unclear whether the inci-

dence or the age and sex distribution applies to populations not

yet studied elsewhere in the world. In 1 survey of US medical

practices, the classication of patients with rhinitis was 43%

AR, 23% NAR, and 34% mixed rhinitis (rhinitis with both AR

and NAR features).

1

These data suggest that at least 57% of

rhinitis patients have some contribution from NAR causing

their rhinitis symptoms. Similar European studies have found

that approximately 1 in 4 patients complaining of nasal symp-

toms has pure NAR.

2

Recent estimates suggest that 50 million

Europeans have NAR, with a total prevalence of greater than

200 million worldwide.

3

In the United States, there are ap-

proximately 60 million patients with AR and 30 million with

nonallergic vasomotor rhinitis (VMR).

Nonallergic rhinitis tends to be adult onset, with the

typical age of presentation between 30 and 60 years.

4

Once

symptoms begin, they frequently last a lifetime. If NAR is

present in pediatric populations, it is more likely to be ana-

tomic in nature and to be caused by either adenoid or turbinate

hypertrophy, leading to persistent nasal obstruction. In adults,

most studies report a clear female predominance, with esti-

mates ranging from 58% to 71% of those affected being fe-

male. In a Danish study classifying a population of both adults

and adolescents, female predominance held true with ap-

proximately double the prevalence of NAR in women.

2

The nancial impact of NAR has not been studied

directly, but numerous studies have looked at the direct and

the indirect costs of AR. It is likely that because most studies

indicate that at least 1 in 4 patients with nasal symptoms have

pure NAR, the rough cost of the condition is approximately

one third of AR. Direct and indirect US medical expendi-

tures for AR are in excess of 2.7 billion dollars (1995 dollars).

5

When lost productivity due to drowsiness, cognitive/motor

impairment, and missed school and work is considered, the

cost estimate increases to $6 billion.

6

Thus, although no re-

ports of the costs of NAR have been reported, it is likely that

this disease costs at least US$2 to 3 billion per year.

NAR: DIAGNOSIS AND CLASSIFICATION

Nonallergic rhinitis denotes a group of heterogeneous

syndromes with distinct underlying pathophysiologies. His-

torically, NAR variants have been divided into 2 groups

based on nasal cytology: NAR with eosinophilia syndrome

(NARES) and non-NARES. However, in this era, nasal cy-

tology is rarely performed in clinical practice. Thus, it is

logical today to classify NAR based solely on symptoms and

triggers. Furthermore, when considering the diagnosis of

NAR, the concomitant presence of AR and/or chronic rhino-

sinusitis needs to be considered. Most patients with chronic

nasal symptoms appear at the physicians ofce assuming that

they have AR. As part of the diagnostic steps used to conrm

the diagnosis, most patients undergo specic environmental

REVIEW ARTICLE

20 WAO Journal & March 2009

Received for publication October 21, 2008; accepted December 16, 2008.

From the Institute for Asthma & Allergy, Bethesda, MD.

Reprints: Michael A. Kaliner, MD, Institute for Asthma & Allergy, 6515

Hillmead Road, Bethesda, MD 20817. E-mail: makaliner@aol.com.

Copyright * 2009 by World Allergy Organization

allergy testing either by skin test or by radioallergosorbent test.

In the presence of negative allergy skin tests and a history of

rhinitis symptoms, most patients will have some form of NAR

or rhinosinusitis.

Nonallergic rhinitis can be classied into 9 subtypes

(Table 1): drug-induced rhinitis, gustatory rhinitis (rhinorrhea

associated with eating), hormonal-induced rhinitis, infectious

rhinitis, NARES, occupational rhinitis, senile rhinitis, atrophic

rhinitis, and VMR (modied from Settipane and Charnock

4

).

Rhinitis of pregnancy is an extremely common condition

effecting up to 20% to 30% of pregnancies, especially nota-

ble during the last trimester.

7

It typically resolves spontane-

ously within 2 weeks of delivery. As 1 clue to specic causes,

Ellegard et al

8

have shown that woman with rhinitis of preg-

nancy have elevated serum placental growth hormone levels

when compared with pregnant women without rhinitis. How-

ever, it is usually assumed that the rhinitis of pregnancy

reects the mucosal engorgement found in the last trimester

as a consequence of progesterone stimulation. Thus, the nasal

mucosa also becomes engorged and congestion ensues.

Rhinitis medicamentosa or medication-induced rhinitis

is another common NAR variant. The most common cause of

rhinitis medicamentosa is overuse of the topical nasal decon-

gestants oxymetazoline or phenylephrine. When used briey

(less than 3Y5 days consecutively), these medications provide

signicant relief of nasal congestion. However, with chronic

use, rebound nasal congestion can occur and can be quite se-

vere. The exact mechanism is poorly understood, but theories

involving recurrent nasal tissue hypoxia and negative neural

feedback with chronic >-2 receptor agonism exist.

9

Rhinitis

medicamentosa is treated with topical nasal corticosteroids

(NCCSs) and/or oral corticosteroids, and progressive with-

drawal of the topical decongestant sprays over a 3- to 7-day

period.

More broadly, other medications can cause chronic nasal

symptoms through a host of different mechanisms. Antihy-

pertensive medications including A blockers, reserpine, cal-

cium channel blockers, and methyldopa frequently cause nasal

congestion.

1

Aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inammatory

drugs also may contribute to congestion especially in patients

with a history of nasal polyposis. Oral contraceptive pills also

can cause congestion in some women. Eye drops can cause rhi-

nitis after they pass the nasolacrimal duct into the nose.

Nonallergic rhinitis also is also found with other un-

derlying medical conditions, the full range of which is beyond

the scope of this article (Table 2). For example, nasal conges-

tion can be seen in disparate diseases such as hypothyroidism

and chronic fatigue syndrome. Baraniuk et al

10

found that 46%

of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome have NAR and that

76% of patients have some nasal complaints. Gastroesopha-

geal reux disease or laryngeal-pharyngeal reux can lead to

chronic postnasal drip and other throat symptoms and, in se-

vere cases, can also cause nasal congestion.

Anatomic anomalies can contribute to NAR. Both

adenoid hypertrophy and turbinate hypertrophy can cause

symptoms of chronic nasal congestion with little relief from

medications. Surgical intervention can be curative. Quite dis-

similar to the anatomic hypertrophies, senile rhinitis is most

common in the elderly and can lead to persistent rhinorrhea,

worsened by eating or environmental irritants. Atrophic rhi-

nitis is usually seen in patients who have had overzealous

surgeries, with too much mucus-secreting tissues removed.

Cerebral spinal uid leak in patients with a history of cra-

niofacial trauma or past facial/sinus surgeries must be con-

sidered when evaluating persistent rhinorrhea.

Nonallergic VMR

The most frequent form of NAR observed clinically is

nonallergic VMR or idiopathic rhinitis, characterized by spo-

radic or persistent nasal symptoms that are triggered by

environmental conditions, such as strong smells; exposure to

cold air; changes in temperature, humidity, and barometric

pressure; strong emotions; ingesting alcoholic beverages; and

changes in hormone levels. The diagnosis of VMR is primarily

made by clinical history. If a patient has appropriate nasal

symptoms (usually rhinorrhea, congestion, postnasal drip,

headaches, throat clearing, and coughing) triggered by 1 or

more environmental irritants, then VMR is present. Concomi-

tant ocular symptoms tend to be minimal, and the symptoms

of nasal and palatal itch as well as sneezing spells are not

common. Unlike AR, VMR is usually of adult onset and not

worsened by exposure to classic allergens such pollen, house

dust mite, dog, or cat. A validated questionnaire has been

created to help identify NAR patients.

11

Because VMR may be

caused by shifts in temperature and humidity, patients may

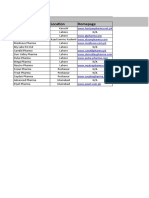

TABLE 1. Specic Syndromes Classied as NAR

Drug-induced rhinitis, including rhinitis medicamentosa

Gustatory rhinitis

Hormonal-induced rhinitis, including the rhinitis of pregnancy

Infectious rhinitis

NARES

Occupational rhinitis

Senile rhinitis

Atrophic rhinitis

Vasomotor or idiopathic rhinitis

TABLE 2. Medical Conditions Associated With or Presenting

Similarly to NAR

Metabolic

Acromegaly

Pregnancy

Hypothyroidism

Autoimmune

Sjogren syndrome

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Relapsing polychondritis

Churg-Straus syndrome

Wegner granulomatosis

Other

Cystic fibrosis

Kartagener syndrome

Sarcoidosis

Immunodeficiency

Adapted from Settipane and Settipane.

1

WAO Journal & March 2009 Nonallergic Rhinitis and Vasomotor Rhinitis

* 2009 World Allergy Organization 21

experience seasonal symptoms during spring and fall. Thus,

seasonal VMR can easily be confused with Seasonal Allergic

Rhinitis (SAR).

12

The diagnosis of VMR is based solely on the patients

history of symptoms and their triggers, whereas the diagnosis

of AR requires an appropriate history and conrmatory allergy

testing, either positive prick skin tests or radioallergosorbent

tests. These diseases are not mutually exclusive, and nearly

60% of AR patients have a component of VMR participating

in triggering symptoms. In 1 survey of patients with chronic

rhinosinusitis, AR was the underlying cause in 65%, whereas

VMR was coexistent in 25%.

13

Thus, there is an extensive

overlap between the 3 most common chronic nasal diseases:

AR, VMR, and chronic rhinosinusitis.

The exact underlying mechanisms causing VMR are not

well understood. There is evidence that capsaicin-sensitive

nociceptors in the nasal mucosa may play a role.

14Y16

Other

studies have shown that in patients with cold-airYinduced

NAR, inhalation of cold air into 1 nostril causes contralateral

symptoms that can be blocked by pretreating the challenged

nostril with lidocaine or repetitively treating the nose with

capsaicin before challenge.

17,18

Further evidence of a neu-

rologic mechanism driving NAR is a small study suggesting

that endoscopic vidian neurectomy reduces both rhinorrhea

and congestion in VMR patients.

19

Some studies have also

demonstrated that topical nasal capsaicin treatment of VMR

patients can induce prolonged symptom relief.

15

By contrast,

there is some data that mast cells can be activated in cold-

airYinduced rhinitis by breathing cold dry air, which caused in

vivo histamine release in cold-airYinduced rhinitis but not in

other forms of VMR.

20

The epidemiologic predominance of females experien-

cing VMR suggests that female hormones might play some

role, but there is no research explaining this possibility.

TREATMENT

Although each form of NAR should be treated indi-

vidually, VMR is the most well-studied and clinically im-

portant form of NAR and the only type of NAR for which

clinical studies have led to approved treatments. In the fol-

lowing discussion, treatment of NAR will focus on VMR, but

some mention will be made of other forms of NAR where

appropriate. The medications used for treating VMR have

been studied less extensively than those for AR, but there are

still multiple therapeutic options available (Fig. 1). In Figure 1,

the algorithm is based on separation of VMR into 3 clinical

presentations: congestion predominant, rhinorrhea predomi-

nant, and mixed form of VMR where patients experience both

rhinorrhea and congestion.

Nasal Corticosteroids

Nasal corticosteroids treat inammatory conditions

regardless of etiology. There is substantial evidence that cor-

ticosteroids benet AR, some forms of NAR including VMR,

and chronic rhinosinusitis. In a study of 983 patients with

NARES and non-NARES, uticasone propionate (FP) at both

200 and 400 Kg signicantly improved total nasal symptoms

scores when compared with placebo, and no difference was

noted between the 2 concentrations.

21

In the United States, of

all the NCCSs approved by the Food and Drug Authority

(FDA) available today, only FP is approved for the treatment

of both AR and NAR.

Although none of the other current NCCS has received

US FDA approval for use in NAR, there is some supportive

data for the efcacy of intranasal budesonide and mometasone

in some patients with perennial rhinitis.

22,23

There is also 1

published study demonstrating that there was no benet from

FP in NAR. In that study, NAR patients receiving 200 Kg of

daily FP showed a reduction in inammatory mediators but no

improvement in symptoms as compared with placebo.

14

By

contrast, clinical experience suggests that all NCCSs have

some effectiveness in treating VMR.

In VMR, the scent of uticasone is sometimes a negative

feature in patients for whom scent is a trigger. However, as a

class, NCCS treats the broadest spectrum of NAR symptoms

and seems to have at least some degree of efcacy in all NAR

FIGURE 1. Algorithm for the treatment of nonallergic VMR. Once a patient is categorized as VMR, the predominant symptom

complex determines initial treatments based on symptom severity. Initial treatments for mildly affected patients use single entities,

but patients with more severe disease who have failed monotherapy should be tried on combination therapies. Most patients will

ultimately respond to the use of combinations of nasal sprays plus an oral medication. Once under control, stepping the therapy

down to the lowest effective dose of mediations is suggested.

Scarupa and Kaliner WAO Journal & March 2009

22 WAO Journal & March 2009

variants, including VMR. Thus, for the treatment of NAR,

NCCSs are considered a rst-line therapy.

Antihistamines

It is quite likely that all NAR patients have tried oral

antihistamines, either in the form of over-the-counter medi-

cations or as prescribed by physicians who assume that the

symptoms are caused by allergies. Histamine release has not

been seen in NAR and is specically not seen in VMR other

than cold-airYinduced rhinitis.

20

Thus, the use of oral antihis-

tamines makes little sense, and these medications have rarely

been studied in VMR. A 1982 study does show that rst-

generation antihistamines can improve VMR symptoms when

combined with a decongestant.

24

It is predictable that rst-generation antihistamines

might reduce rhinorrhea through anticholinergic actions,

whereas second-generation nonsedating antihistamines have

minimal anticholinergic activity. Typically, second-generation

oral antihistamines are of no benet in NAR. Oral antihis-

tamines are generally ineffective in reducing congestion in

AR and thus would not be expected to work in NAR either.

The combination of an antihistamine and a decongestant might

help reduce the congestion seen in VMR, but no such indi-

cation has been approved by the US FDA. Clinical experience

suggests that antihistamine/decongestant combinations are

somewhat effective in VMR.

By contrast, intranasal antihistamines are very effective

in treating AR (both azelastine and olopatadine are approved

for treating SAR). Azelastine is also approved by the FDA for

treatment of nonallergic VMR. Although azelastine is pri-

marily an antihistamine, it is unlikely that its efcacy in VMR

is due to histamine receptor blockade. Instead, it is probably

azelastines actions as an anti-inammatory and neuroinam-

matory blocker that makes this medication useful in treating

VMR or NAR. Azelastine has been shown to deplete inam-

matory neuropeptides in the nasal mucosa; to reduce levels of

proinammatory cytokines, leukotrienes, and cell adhesion

molecules; and to inhibit mast cell degranulation.

25

In 2 multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-

controlled, parallel-group clinical trials, azelastine showed

considerable efcacy in the treatment of each of the symptoms

of VMR or NAR, including congestion.

26

Treatment over 21

days caused a signicant reduction in the total VMR symptom

score from baseline when compared with placebo (P = 0.002),

and every nasal symptom was effectively reduced. Symptom

improvement was rapid with most patients experiencing relief

within 1 week. There were no serious adverse events, although

a bitter taste was experienced by some in the azelastine group.

In studies of AR, onset of effect with nasal azelastine is seen in

15 to 30 minutes.

25

A meta-analysis has suggested that NCCSs are slightly

more effective than azelastine in the treatment of AR, but no

such analyses exist comparing these products in treating

NAR.

27

When NCCS and azelastine were combined in the

treatment of AR, the effects of the combination were additive.

In a randomized double-blind trial comparing FP alone versus

azelastine alone versus the two in combination for the treat-

ment of AR, the combination produced a further 40% reduc-

tion in total nasal symptom scores as compared with either FP

or azelastine alone. The combination of FP and azelastine

reduced congestion by 48% compared with the individual

components.

28

The combination has yet to be studied in VMR

or NAR, but extensive clinical experience suggests that this

combination is highly effective in VMR as well. On the basis

of both published clinical studies and extensive clinical expe-

rience, the use of azelastine (and possibly olopatadine) alone

and in combination with NCCS is a preferred rst-line treat-

ment of VMR/NAR as well as AR.

Anticholinergics

Ipratropium bromide (IB) is a potent intranasal anti-

cholinergic with utility in the treatment of rhinorrhea in AR

and NAR. It has been studied in both adults and children.

Ipratropium bromide specically treats rhinorrhea and does

little to improve congestion. Intranasal anticholinergics work

best for rhinorrhea predominant NAR variants such as cold-

airYinduced rhinitis (skiers nose)

29

and gustatory and senile

rhinitis.

30

In 28 patients with cold-airYinduced rhinitis, IB

reduced the symptoms and the number of tissues required

during and after cold exposure (P = 0.0007 and 0.0023, res-

pectively).

31

In children with perennial AR or NAR, the effect

of IB was superior to placebo and equivocal to beclometha-

sone dipropionate (BD) for the treatment of both rhinorrhea

and congestion. However, IB was less effective than BD for

controlling sneezing.

32

Similar to the nasal antihistamines, there seems to be an

additive effect when IB is used in conjunction with NCCSs.

33

In a study comparing beclomethasone versus IB versus the two

combined, the combination group had better symptom control

of rhinorrhea. Beclomethasone monotherapy was found to

better treat sneezing and congestion than IB monotherapy.

Both medications were very well tolerated.

Oral anticholinergics such as methscopolamine have

not been studied in NAR but likely improve symptoms par-

ticularly in rhinorrhea predominant disease or in patients with

signicant postnasal drainage. Many rst-generation antihis-

tamines and decongestants also have strong anticholinergic

properties. However, side effects such as dry mouth, sedation,

and urinary hesitancy limit the usefulness of these drugs.

Clinical experience suggests that oral methscopolamine com-

bined with an oral rst-generation antihistamine is helpful in

treating patients with postnasal drip and that adding this com-

bination to nasal IB, nasal antihistamines, or NCCS is useful.

Decongestants

Both oral and topical decongestants effectively treat

congestion regardless of cause; however, none have been

studied for NAR. Oral pseudoephedrine is an effective decon-

gestant and can be considered for chronic use. However, side

effects such as neurogenic and cardiac stimulation, palpita-

tions, and insomnia affect a signicant number of patients.

Furthermore, the medication is relatively contraindicated in

patients with hypertension. Thus, pseudoephedrine must be

used cautiously. Phenylephrine is also an oral decongestant. It

has been studied far less than pseudoephedrine and is con-

sidered a generally less potent medication.

Topical decongestants such as oxymetazoline and phen-

ylephrine are fast acting potent local decongestants. These

WAO Journal & March 2009 Nonallergic Rhinitis and Vasomotor Rhinitis

* 2009 World Allergy Organization 23

medications cannot be used chronically because continual use

for more than 3 to 10 days leads to rhinitis medicamentosa. For

NAR patients with intermittent nasal congestion, a topical de-

congestant can be used for short-term relief of congestion.

Other NAR Therapies

Although NAR effects many patients, very few medica-

tions have been adequately studied for the treatment of

this condition. In patients who do not adequately respond to

NCCSs, intranasal antihistamines, or IB, other agents can be

considered. There are a fewlimited studies examining intranasal

capsaicin in NAR. In theory, repetitive capsaicin application

depletes certain neuroinammatory chemicals. Van Rijswijk

et al

18

did demonstrate decreased nasal symptoms in VMR

patients treated with capsaicin. Similarly, botulinum toxin A

injected into the inferior and middle turbinates of patients

with NAR has been shown to decrease congestion, sneezing,

rhinorrhea, and nasal itch.

34

In patients with congestion-

predominant NAR and turbinate hypertrophy, surgical reduc-

tion of the inferior turbinates may be of some benet.

35

Nasal

washing with isotonic or hypertonic saline has a demonstrated

benet particularly in chronic rhinosinusitis and seems to benet

some NARpatients.

36

Antileukotrienes have not been studied in

NAR, but there is at least some theoretical benet inpatients with

aspirin sensitivity and/or nasal polyposis. One controlled trial

has demonstrated some efcacy using acupuncture in NAR.

37

CONCLUSIONS

Nonallergic rhinitis is an underrecognized and inade-

quately treated condition affecting many subjects. Diagnosis

is dependent on a thorough history and exclusion of other

underlying conditions, including ARand chronic rhinosinusitis.

Nonallergic rhinitis tends to require chronic medical manage-

ment, and use of topical NCCSs and nasal antihistamines, used

alone or in combination, is very effective in most patients. This

combination is also extremely effective in treating AR. Thus,

recognizing that the combination of both NCCSs and nasal anti-

histamines effectively treat AR, VMR, and mixed rhinitis, this

combination of medications seems to be a useful rst-line treat-

ment for the overwhelming majority of rhinitis patients.

REFERENCES

1. Settipane RA, Settipane GA. Nonallergic rhinitis. In: Kaliner MA, editor.

Current Review of Rhinitis. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Current Medicine;

2006:55Y68.

2. Molgaard E, Thomsen SF, Lund T, Pedersen L, Nolte H, Backer V.

Differences between allergic and nonallergic rhinitis in a large sample of

adolescents and adults. Allergy. 2007;62(9):1033Y1037.

3. Bousquet J, Fokkens W, Burney P, Durham SR, Bachert C, Akdis CA,

et al. Important research questions in allergy and related diseases:

nonallergic rhinitis: a GALEN paper. Allergy. 2008;63:842Y853.

4. Settipane RA, Charnock DR. Epidemiology of rhinitis: allergic and

nonallergic. In: Baraniuk JN, Shusterman D, editors. Nonallergic Rhinitis.

New York: Informa; 2007:23Y34.

5. Ross RN. The costs of allergic rhinitis. Am J Manag Care. 1996;2:

285Y290.

6. Ray NF, Baraniuk JN, Thamer M, Rinehart CS, Gergen PJ, Kaliner M,

et al. Direct expenditures for the treatment of allergic rhinoconjuctivitis in

the United States in 1996, including contributions of related airway

illnesses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103:401Y407.

7. Ellegard EK. Clinical and pathogenetic characteristics of pregnancy

rhinitis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2004;26(3):149Y159.

8. Ellegard E, Oscarsson J, Bougoussa M, Igout A, Hennen G, Eden S, et al.

Serum level of placental growth hormone is raised in pregnancy rhinitis.

Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124(4):439Y443.

9. Graf PM. Rhinitis medicamentosa. In: Baraniuk JN, Shusterman D,

editors. Nonallergic Rhinitis. New York: Informa; 2007:295Y304.

10. Baraniuk JN, Clauw DJ, Gaumond E. Rhinitis symptoms in

chronic fatigue syndrome. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1998;81(4):

359Y365.

11. Brandt D, Bernstein JA. Questionnaire evaluation and risk factor

identification for Nonallergic vasomotor rhinitis. Ann Allergy Asthma

Immunol. 2006;96(4):526Y532.

12. Wedback A, Enbom H, Eriksson NE, Moverare R, Malcus I. Seasonal

nonallergic rhinitis (SNAR)Va new disease entity? Rhinology.

2005;43:86Y92.

13. McNally PA, White MV, Kaliner MK. Sinusitis in an allergists office:

analysis of 200 consecutive cases. Allergy Asthma Proc. 1997;18:169Y176.

14. Blom HM, Godthelp T, Fokkens WJ, Klein Jan A, Mulder PGM,

Rijntjes F. The effect of nasal steroid aqueous spray on nasal complaint

scores and cellular infiltrates in the nasal mucosa of patients with

nonallergic, noninfectious perennial rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol.

1997;100:739Y747.

15. Blom HM, Van Rijswijk JB, Garrelds IM, Mulder PG, Timmermans T,

Gerth van Wijk R. Intranasal capsaicin is efficacious in nonallergic,

noninfectious rhinitis. A placebo-controlled study. Clin Exp Allergy.

1997;27:1351Y1358.

16. Sarin S, Undem B, Sanico A, Togias A. The role of the nervous system

in rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:999Y1014.

17. Philip G, Jankowski R, Baroody F, Naclerio R, Togias A. Reflex

activation of nasal secretion by unilateral inhalation of cold dry air.

Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:1616Y1622.

18. Van Rijswijk JB, Boeke EL, Keizer JM, Mulder PGH, Blom HM,

Fokkens WJ. Intranasal capsaicin reduces nasal hyperreactivity in

idiopathic rhinitis: a double-blind randomized application regimen study.

Allergy. 2003;58:754Y761.

19. Robinson SR, Wormald P. Endoscopic vidian neurectomy. Am J Rhinol.

2006;20(2):197Y202.

20. Togias A, Lykens K, Kagey-Sobotka A, Eggleston PA, Proud D,

Lichtenstein LM, et al. Studies on the relationships between sensitivity

to cold, dry air, hyperosmolal solutions and histamine in the adult nose.

Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;141(6):1428Y1433.

21. Webb RD, Meltzer EO, Finn AF, Rickard KA, Pepsin PJ, Westlund R,

et al. Intranasal fluticasone propionate is effective for perennial

nonallergic rhinitis with or without eosinophilia. Ann Allergy Asthma

Immunol. 2002;88:385Y390.

22. Day JH, Andersson CB, Briscoe MP. Efficacy and safety of intranasal

budesonide in the treatment perennial rhinitis in adults and children.

Ann Allergy. 1990;64(5):445Y450.

23. Lundblad L, Sipila P, Farstad T, Drozdziewicz D. Mometasone furoate

nasal spray in the treatment of perennial non-allergic rhinitis: a Nordic,

multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Acta

Otolaryngol. 2001;121(4):505Y509.

24. Broms P, Malm L. Oral vasoconstrictors in perennial non-allergic rhinitis.

Allergy. 1982;37:67Y74.

25. Kaliner MA. A novel and effective approach to treating rhinitis with nasal

antihistamines. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;99:383Y391.

26. Banov CH, Lieberman P. Vasomotor Rhinitis Study Groups. Efficacy of

azelastine nasal spray in the treatment of vasomotor (perennial

nonallergic) rhinitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2001;86(1):

28Y35.

27. Yanez A, Rodrigo GJ. Intranasal corticosteroids versus topical H1

receptor antagonists for the treatment of allergic rhinitis: a systematic

review with meta-analysis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;89:

479Y484.

28. Ratner PH, Findlay SR, Hampel F Jr, van Bavel J, Widlitz MD, Freitag JJ,

et al. A double-blind, controlled trial to assess the safety and efficacy

of azelastine nasal spray in seasonal allergic rhinitis. J Allergy Clin

Immunol. 1994;94(5):818Y825.

29. Silvers WS. The skiers nose: a model of cold-induced rhinorrhea. Ann

Allergy. 1991;67:32Y36.

30. Raphael G, Raphael MH, Kaliner MA. Gustatory rhinitis: a syndrome of

food induced rhinorrhea. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1989;83(1):110Y115.

31. Bonadonna P, Senna G, Zanon P, Cocco G, Dorizzi R, Gani F, et al.

Scarupa and Kaliner WAO Journal & March 2009

24 WAO Journal & March 2009

Cold-induced rhinitis in skiers-Clinical aspects and treatment with

ipratropium bromide nasal spray: a randomized controlled trial. Am J

Rhinol. 2001;15:297Y301.

32. Milgrom H, Biondi R, Georgitis JW, Meltzer EO, Munk ZM, Drda K,

et al. Comparison of ipratropium bromide 0.03% with beclomethasone

dipropionate in the treatment of perennial rhinitis in children. Ann Allergy

Asthma Immunol. 1999;83(2):105Y111.

33. Dockhorn R, Aaronson D, Bronsky E, Chervinsky P, Cohen R,

Ehtessabian R, et al. Ipratropium bromide nasal spray 0.03% and

beclomethasone nasal spray alone and in combination for the treatment

of rhinorrhea in perennial rhinitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol.

1999;82(4):349Y359.

34. Ozcan C, Vayisoglu Y, Dogu O Gorur K. The effect of intranasal injection

of botulinum toxin A on the symptoms of vasomotor rhinitis. Am J

Otolaryngol. 2006;27(5):314Y318.

35. Ikeda K, Oshima T, Suzuki M, Suzuli H, Shimomura A. Functional

inferior turbinosurgery (FITS) for the treatment of resistant chronic

rhinitis. Acta Otolaryngol. 2006;126:739Y745.

36. Scarupa MD, Kaliner MA. Adjuvant therapies in the treatment of

acute and chronic rhinosinusitis. In: Hamilos D and Baroody F,

editors. Chronic Rhinosinusitis. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2007.

37. Davies A, Lewith G, Goddard J Howarth P. The effect of acupuncture on

nonallergic rhinitis: a controlled pilot study. Altern Ther Health Med.

1998;4(1):70Y74.

WAO Journal & March 2009 Nonallergic Rhinitis and Vasomotor Rhinitis

* 2009 World Allergy Organization 25

Вам также может понравиться

- 10 1 1 126Документ60 страниц10 1 1 126Manfred GithinjiОценок пока нет

- Ajr 10 460h0Документ6 страницAjr 10 460h0Raga ManduaruОценок пока нет

- Msds 2 PDFДокумент5 страницMsds 2 PDFRaga ManduaruОценок пока нет

- Treatment of Hypertension: JNC 8 and More: Pharmacist'S Letter / Prescriber'S LetterДокумент6 страницTreatment of Hypertension: JNC 8 and More: Pharmacist'S Letter / Prescriber'S LetterJen CanlasОценок пока нет

- Uterine Sarcoma in Patients Operated On For.17Документ3 страницыUterine Sarcoma in Patients Operated On For.17Raga ManduaruОценок пока нет

- Cholera Epidemic Associated With Consumption of Unsafe Drinking WaterДокумент6 страницCholera Epidemic Associated With Consumption of Unsafe Drinking WaterRaga ManduaruОценок пока нет

- Jurnal Luar Lagi GiziДокумент32 страницыJurnal Luar Lagi GiziRaga ManduaruОценок пока нет

- Drugs For The Treatment of Diabetes MellitusДокумент51 страницаDrugs For The Treatment of Diabetes MellitusRaga ManduaruОценок пока нет

- Daftar Pustaka HIV/AIDSДокумент1 страницаDaftar Pustaka HIV/AIDSRaga ManduaruОценок пока нет

- Salmonella in Surface and Ddwringking Water Occurance and Water Mediated Transmission Levantesi - FoodResInter - 2011Документ17 страницSalmonella in Surface and Ddwringking Water Occurance and Water Mediated Transmission Levantesi - FoodResInter - 2011Raga ManduaruОценок пока нет

- Jc180 Hiv Infantfeediscng 3 en 3Документ26 страницJc180 Hiv Infantfeediscng 3 en 3Raga ManduaruОценок пока нет

- SffsfsfsssvsfvsfsdfffeefefwefefefwefДокумент7 страницSffsfsfsssvsfvsfsdfffeefefwefefefwefRaga ManduaruОценок пока нет

- 247 FulldsДокумент68 страниц247 FulldsRaga ManduaruОценок пока нет

- WHO HIV Clinical Staging GuidelinesДокумент49 страницWHO HIV Clinical Staging Guidelinesdonovandube8235Оценок пока нет

- JakartaДокумент7 страницJakartaBachtiar M TaUfikОценок пока нет

- Nasopharyngeal Carriage of Klebsiella Pneumoniae and Other Gram-Negative Bacilli in Pneumonia-Prone Age Groups in Semarang, IndonesiaДокумент3 страницыNasopharyngeal Carriage of Klebsiella Pneumoniae and Other Gram-Negative Bacilli in Pneumonia-Prone Age Groups in Semarang, IndonesiaRaga ManduaruОценок пока нет

- New Classification of Ocular Surface BurnsДокумент6 страницNew Classification of Ocular Surface BurnstiaracintyaОценок пока нет

- JJJJДокумент6 страницJJJJRaga ManduaruОценок пока нет

- Sat 0715 Breakfast Symposium Donnenfeld BlepharitisДокумент22 страницыSat 0715 Breakfast Symposium Donnenfeld BlepharitisRaga ManduaruОценок пока нет

- SaaaДокумент5 страницSaaaRaga ManduaruОценок пока нет

- Principles of PreventionДокумент14 страницPrinciples of PreventionprecillathoppilОценок пока нет

- Adolescent Issues - Raga ManduaruДокумент102 страницыAdolescent Issues - Raga ManduaruRaga ManduaruОценок пока нет

- Comparison of Maternal and Neonatal OutcomesДокумент8 страницComparison of Maternal and Neonatal OutcomesNuardi YusufОценок пока нет

- Risk Factors and Outcomes Associated With A Short.21Документ9 страницRisk Factors and Outcomes Associated With A Short.21Raga ManduaruОценок пока нет

- New Classification of Ocular Surface BurnsДокумент6 страницNew Classification of Ocular Surface BurnstiaracintyaОценок пока нет

- Risk Factors and Outcomes Associated With A Short.21Документ9 страницRisk Factors and Outcomes Associated With A Short.21Raga ManduaruОценок пока нет

- Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics Volume 289 Issue 4 2014 (Doi 10.1007 - s00404-013-3072-9) Narang, Yum - Vaid, Neelam Bala - Jain, Sandhya - Suneja, Amita - Gu - Is Nuchal Cord JustifiДокумент7 страницArchives of Gynecology and Obstetrics Volume 289 Issue 4 2014 (Doi 10.1007 - s00404-013-3072-9) Narang, Yum - Vaid, Neelam Bala - Jain, Sandhya - Suneja, Amita - Gu - Is Nuchal Cord JustifiRaga ManduaruОценок пока нет

- Figure 1 The Role of Insulin Resistance in Diabetic DyslipidemiaДокумент1 страницаFigure 1 The Role of Insulin Resistance in Diabetic DyslipidemiaRaga ManduaruОценок пока нет

- Pathology Journal Reading: Presented by Intern 曾德朋Документ33 страницыPathology Journal Reading: Presented by Intern 曾德朋Raga ManduaruОценок пока нет

- Keg Aw at Daru RatanДокумент25 страницKeg Aw at Daru RatanRaga ManduaruОценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Mal UnionДокумент10 страницMal UnionYehuda Agus SantosoОценок пока нет

- AAO Glaucoma 2013 - GLA - Syllabus PDFДокумент96 страницAAO Glaucoma 2013 - GLA - Syllabus PDFrwdОценок пока нет

- Week - 4 - H2S (Hydrogen Sulfide) Facts W-Exposure LimitsДокумент2 страницыWeek - 4 - H2S (Hydrogen Sulfide) Facts W-Exposure LimitsLọc Hóa DầuОценок пока нет

- How I Do CMR Scanning Safely: Elisabeth Burman Research Sister Royal Brompton Hospital, London UKДокумент41 страницаHow I Do CMR Scanning Safely: Elisabeth Burman Research Sister Royal Brompton Hospital, London UKYuda FhunkshyangОценок пока нет

- 6/27/2019 NO NAMA BARANG QTY UOM Batch EDДокумент8 страниц6/27/2019 NO NAMA BARANG QTY UOM Batch EDRedCazorlaОценок пока нет

- List of HospitalsДокумент48 страницList of HospitalsragpavОценок пока нет

- Poster ROICAM 2018Документ1 страницаPoster ROICAM 2018ibrahimОценок пока нет

- IP Sterility TestingДокумент6 страницIP Sterility TestingVarghese100% (3)

- Estradiol Valerate + Dienogest PDFДокумент6 страницEstradiol Valerate + Dienogest PDFJuan FernandezОценок пока нет

- English 2 Class 03Документ32 страницыEnglish 2 Class 03Bill YohanesОценок пока нет

- ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY of RabiesДокумент5 страницANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY of RabiesDavid CalaloОценок пока нет

- Initiatives of FSSAIДокумент27 страницInitiatives of FSSAIAshok Yadav100% (2)

- BarryKuebler Lesson1 AssignmentДокумент4 страницыBarryKuebler Lesson1 AssignmentBarry KueblerОценок пока нет

- Aghamohammadi Et Al 2016 WEB OF SCIENCE Integrative Cancer TherapiesДокумент9 страницAghamohammadi Et Al 2016 WEB OF SCIENCE Integrative Cancer Therapiesemmanuelle leal capelliniОценок пока нет

- Voice Production in Singing and SpeakingBased On Scientific Principles (Fourth Edition, Revised and Enlarged) by Mills, Wesley, 1847-1915Документ165 страницVoice Production in Singing and SpeakingBased On Scientific Principles (Fourth Edition, Revised and Enlarged) by Mills, Wesley, 1847-1915Gutenberg.org100% (3)

- 3401 Review On Goat Milk Composition and Its Nutritive ValueДокумент10 страниц3401 Review On Goat Milk Composition and Its Nutritive ValueRed DiggerОценок пока нет

- Evidence-Based Recommendations For Natural Bodybuilding Contest Preparation: Nutrition and Supplementation by Eric Helms, Alan Aragon, and Peter FitschenДокумент40 страницEvidence-Based Recommendations For Natural Bodybuilding Contest Preparation: Nutrition and Supplementation by Eric Helms, Alan Aragon, and Peter FitschenSixp8ck100% (3)

- Systematic Reviews of Interventions Following Physical Abuse: Helping Practitioners and Expert Witnesses Improve The Outcomes of Child Abuse, UK, 2009Документ6 страницSystematic Reviews of Interventions Following Physical Abuse: Helping Practitioners and Expert Witnesses Improve The Outcomes of Child Abuse, UK, 2009Beverly TranОценок пока нет

- VP ShuntДокумент5 страницVP ShuntPradeep SharmaОценок пока нет

- Melanoma Cancer PresentationДокумент13 страницMelanoma Cancer PresentationMerlyn JeejoОценок пока нет

- Femoral Fractures in Children: Surgical Treatment. Miguel Marí Beltrán, Manuel Gutierres, Nelson Amorim, Sérgio Silva, JorgeCoutinho, Gilberto CostaДокумент5 страницFemoral Fractures in Children: Surgical Treatment. Miguel Marí Beltrán, Manuel Gutierres, Nelson Amorim, Sérgio Silva, JorgeCoutinho, Gilberto CostaNuno Craveiro LopesОценок пока нет

- End users' contact and product informationДокумент3 страницыEnd users' contact and product informationمحمد ہاشمОценок пока нет

- Phobic EncounterДокумент1 страницаPhobic EncounterEmanuel PeraltaОценок пока нет

- Joyetech Eroll Manual MultilanguageДокумент9 страницJoyetech Eroll Manual MultilanguagevanlilithОценок пока нет

- Radial Club Hand TreatmentДокумент4 страницыRadial Club Hand TreatmentAshu AshОценок пока нет

- Vaginitis: Diagnosis and TreatmentДокумент9 страницVaginitis: Diagnosis and TreatmentAbigail MargarethaОценок пока нет

- Parallax Xray For Maxillary CanineДокумент3 страницыParallax Xray For Maxillary Canineabdul samad noorОценок пока нет

- MMMM 3333Документ0 страницMMMM 3333Rio ZianraОценок пока нет

- CRRT Continuous Renal Replacement Therapies ImplementationДокумент28 страницCRRT Continuous Renal Replacement Therapies ImplementationyamtotlОценок пока нет

- Copy (1) of New Text DocumentДокумент2 страницыCopy (1) of New Text DocumentAkchat JainОценок пока нет