Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Brian Thinking

Загружено:

Noorleha Mohd YusoffОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Brian Thinking

Загружено:

Noorleha Mohd YusoffАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

1

DAV04854

The reIationship between teacher efficacy and higher order

instructionaI emphasis

Dr Brian Davies

NSW Department of Education and Training

Introduction

n educational research there is a consensus that the teaching of higher order

thinking is important (Raudenbush, Rowan, and Cheong,1993: 524).

Research suggests, though, that there is a concentration on lower level

thinking in classrooms rather than higher level thinking (Edwards, 1995).

Examination of what motivates teachers towards certain behaviours can be

explained by the construct of teacher efficacy which has been linked to critical

instructional decisions (Tschannen-Moran et al., 1998).

The purpose of this research was to investigate the relationship between

teacher efficacy and the emphasis that teachers placed on higher order

thinking in their teaching programs. n the study, this emphasis on higher

order thinking was labelled " higher order instructional emphasis.

The research examined teaching in New South Wales government schools in

the subject areas of history and science in Year 7 to Year 10. These years

constitute the first four years of high school.

To reach a conclusion on the importance of the contribution of teacher

efficacy to any variance in higher order instructional emphasis it was

appropriate to examine the contribution of other independent variables. These

variables included the year level of the class and the nature of the class, with

the latter referring to whether the class was graded.

ReIated Iiterature

Teacher efficacy

The construct of teacher efficacy was derived from Bandura's theory of self-

efficacy (1977). Applied to the context of education teacher efficacy has been

defined as "the extent to which teachers believe they can affect student

learning (Dembo & Gibson, 1985:173). Teacher efficacy is seen as a

multidimensional construct with Ashton and Webb (1982), for example,

identifying two dimensions as "teaching efficacy and "personal efficacy . The

first factor represents a teacher's sense of teaching efficacy or belief that

teachers can overcome factors external to the teacher such as the

background of students. The second dimension, personal efficacy, is the

belief of an individual teacher in their own personal capacity to deliver the

necessary teaching behaviours to influence student learning.

2

Studies have shown that these two dimensions are independent (Woolfolk

and Hoy, 1990: 82). Ross (1992) found little correlation between teaching

efficacy and personal efficacy. This means that individual teachers could

believe, for example, that teaching can significantly determine what students

learn but that they are not capable of having much of an effect on the learning

of their own students.

Researchers have also questioned whether there are three rather than two

dimensions to the construct of teacher efficacy. For example Guskey (1988)

suggested the possibility of a third dimension following his study of

elementary and high school teachers' sense of responsibility for positive and

negative student outcomes. n their study of prospective teachers using a

revised version of the sixteen-item Gibson and Dembo Teacher Efficacy Scale

(1984), Woolfolk and Hoy (1990) concluded from the factor loadings that the

construct of teacher efficacy consisted of three dimensions: teaching efficacy;

and, two dimensions of personal efficacy. These two related dimensions were

teachers' sense of personal responsibility for positive student outcomes and

their personal responsibility for negative outcomes.

General organisational literature has linked self-efficacy to work-related

performance including productivity, the ability to manage difficult tasks,

adaptability to new technology and the ability to make better use of their skills

in a changing context than those with lower self-efficacy (Gist and Mitchell,

1992). High self-efficacy improves achievement of outcomes as individuals

persist on tasks and focus on problem solving strategies (Stipek, 1993).

Research suggests that teacher efficacy may underlie critical instructional

decisions including the use of time, classroom management strategies and

questioning techniques (Gibson & Dembo 1984; Saklofske, Michayluk and

Randhawa, 1988; Woolfolk, Rosoff, and Hoy, 1990). Teacher efficacy has

also been shown to be a strong predictor of commitment to teaching

(Coladarci, 1992), adoption of innovations (Midgley, Feldlaufer, and Eccles,

1989) and higher levels of planning and organization (Allinder, 1994).

Teachers with a higher sense of efficacy are less critical of students when

they make mistakes (Ashton and Webb, 1986) and exhibit more enthusiasm

about teaching (Allinder, 1994).

Gibson and Dembo (1984) in a classroom study of eight elementary teachers

concluded that high and low efficacy teachers demonstrated differential

patterns of behaviour in the classroom. While there was not a significant

difference in teacher use of time between high efficacy and low efficacy

teachers in the general categories of total academic and total non academic

time there were differences detected in subcategories of behaviour.

Compared with the low efficacy teachers, the high efficacy teachers spent

less time in small group discussion and more time monitoring and checking

seatwork, in preparation or paperwork and in whole class instruction. High

efficacy teachers also showed significantly more persistence than low efficacy

teachers in leading students to correct responses.

3

Podell and Soodak (1993) found that low efficacy teachers were more likely

than high efficacy teachers to refer students who were difficult to teach to

special services. This was particularly the case with students from low socio

economic backgrounds.

n looking at the two factors of teaching efficacy and personal efficacy that

could underpin teacher efficacy, research has produced mixed results

regarding the significance of teaching efficacy in teacher decision-making.

While research involving prospective teachers (Woolfolk and Hoy; 1990)

found that teaching efficacy was significantly correlated with bureaucratic

orientation and pupil control ideology other studies have found that teaching

efficacy does not relate to teaching behaviours and outcomes but that

personal efficacy does (Saklofske et al.; 1988; Soodak and Podell; 1993).

Soodak and Podell (1996) suggested that there may be a developmental

sequence in relation to teaching efficacy in that prospective teachers' beliefs

about their future field of operation are important until they have actually had

the experience to develop their self-efficacy from their personal experiences.

Studies have found positive correlations between teacher efficacy and student

achievement (Fuller at al., 1982). Berman and McLaughlin's evaluation (1977;

cited Dembo and Gibson, 1985:173) of 100 Title ESEA projects found a

positive relationship between teacher efficacy and the achievement of project

goals, degree of teacher change, continued use of project methods and

materials and increased student performance. Armor et al. (1976 cited Dembo

and Gibson, 1985:173-4) found a positive correlation between teacher

efficacy and progress in reading achievement while Ashton and Webb (1982)

found a significant relationship between teacher efficacy and the performance

of students from high school basic skills classes on the Metropolitan

Achievement Test in mathematics and language.

As an indication of the substantial impact of efficacy on student achievement,

Ashton and Webb (1986) reported that teaching efficacy explained 24 per

cent of variance in mathematic achievement of high school students, while

personal efficacy explained 46 per cent of variance in language performance.

Schunk (1991) found that changes in efficacy improved teacher use of

cognitive strategies and consequent increased performance in mathematics,

reading and writing.

Studies have supported the notion that teachers in more effective schools

have higher levels of efficacy and a greater sense of responsibility for their

students' learning (Brookover and Lezotte 1979 - cited in Guskey and

Passaro; Trentham, Silvern and Brogdon, 1985; Guskey, 1988).

t was expected that teachers who had high self-efficacy were more likely to

emphasise higher order instructional objectives and outcomes than teachers

with low self-efficacy. This was because high efficacy teachers have a

greater belief in their ability to succeed. Furthermore high efficacy teachers

were more likely to have had success with higher order objectives and

outcomes with students in the past because such teachers would make

4

greater efforts to achieve them, would persist in the face of difficulties and

were better able to cope emotionally with problems that arose. This also

meant that the degree of emphasis that high efficacy teachers placed on high

order instructional objectives outcomes was more likely to be successfully

implemented in the classroom.

Higher order instructionaI emphasis

The dependent variable in this study was higher order instructional emphasis.

This was defined as the emphasis that teachers placed on higher order

thinking in their teaching programs and was operationalised through the

emphasis placed on higher order instructional objectives and outcomes in the

Stage 3 and Stage 4 (Year 7 to Year 10) science and history syllabuses in

New South Wales.

Definitions of higher order thinking in the literature indicate its complexity and

many facets. Resnick, for example (1987:3), described higher order thinking

skills as: elaboration of material presented; drawing inferences; analysis; and,

the construction of relationships. The study used Newmann's definition

(1990:44) of higher order thinking as that which "challenges the student to

interpret, analyse, or manipulate information, because a question to be

answered or a problem to be solved cannot be resolved through the routine

application of previously learned knowledge. This definition captured both the

challenge of problem solving and the type of thinking in the higher

taxonomical levels.

This study recognised the importance of higher order thinking in the context of

a subject domain. Higher order thinking then was operationalised in the terms

of the specific curriculum. This was appropriate given the findings from

cognitive research that specific content knowledge plays a fundamental role in

thinking (Resnick, 1987:18).

Teaching for higher order thinking is seen as important for the learning of all

students, whether high or low achieving, and in all subject areas

(Raudenbush, Rowan, and Cheong, 1993: 524). Moreover, Peterson (1988)

asserted that a focus on teaching higher level skills may be particularly

important for low achieving students because they need more support to learn

those skills. Research indicates that lower-achieving students can gain from

the teaching of cognitive processes and knowledge structures (Doyle, 1983).

Studies have shown that average ability students can match the performance

of high ability students if taught problem solving procedures (Clements,1991).

High ability students also benefit from such instruction (Linn, Sloane and

Clancy; 1987). Furthermore, failure to develop higher order thinking skills may

lead to significant learning difficulties even in the primary years ( Resnick,

1987:8).

Specific teacher behaviours that place a focus on problem solving have been

associated with improvements in higher order thinking. For instance, student

5

verbalisation has been linked to improvements in problem solving ability

(Underbakke, Borg and Peterson, 1993: 144).

This study looked at the junior years of high school. Hargreaves and Earl's

(1990) review of research which encompassed this stage of schooling

indicated the importance of higher order thinking during these years. They

noted that one of the developmental tasks of young adolescents is to think in

ways that become progressively more abstract and reflective. Hargreaves,

Earl and Ryan (1996) confirmed the importance of critical and problem solving

skills in students aged ten to fifteen years.

There is evidence that teaching in high schools generally concentrates on

basic skills with teaching of higher order objectives as significantly related to

students in classes classified as high track. For example Raudenbush, Rowan

and Cheong (1993) in a study of high school teachers in sixteen schools in

the United States found that higher order objectives were pursued primarily

for high track students, especially in mathematics and science. Page (1990)

also noted that classes with high-achieving students were more likely to

emphasise higher order instructional goals than classes with low-achieving

students.

Research has examined explanations for variations in teaching for high order

thinking. Raudenbush, Rowan, and Cheong (1993) researched teachers of

mathematics, science, social studies and English in high schools in California

and Michigan to test three explanations for the variation in emphasis on

higher order instructional goals. These were: hierarchical conceptions of

teaching and learning that are part of the curriculum; subject matter and

pedagogical expertise; and, the organizational environment of the school.

The differentiated nature of the curriculum was taken to suggest that the

higher the academic track of the class then the greater would be the

emphasis on higher order instructional objectives. Similarly, the higher the

year level of the class, the greater the emphasis on higher order instructional

objectives that was expected.

Justification for the study

The study was justified firstly because there was a gap in the literature on the

relationship between teacher efficacy and higher order instructional emphasis.

While research into self-efficacy in the context of school education has

identified its relationship with a range of teacher behaviours such as the use

of time, classroom management strategies, questioning techniques and

academic focus (Gibson & Dembo, 1984; Saklofske, Michayluk and

Randhawa, 1988; Woolfolk, Rosoff, and Hoy, 1990) there is a lack of research

on the link with the type of instructional objectives and outcomes emphasised

by teachers. Studies which looked at academic focus, such as the Gibson and

Dembo study (1984), examined academic focus in terms of allocated time and

classroom organization for formal curriculum learning rather than the type of

thinking involved.

6

Furthermore in relation to higher order instructional objectives and outcomes

in school education, the literature discusses the reasons for emphasis in

higher order thinking in terms of organisational characteristics and

conceptions of learning (Raudenbush, Rowan, and Cheong ,1993;

Newmann,1990b) but not in terms of motivational theory.

The research was also justified by the gap in the literature on the

measurement of changes through the junior high school years in higher order

instructional emphasis, particularly in a context such as New South Wales

where there is a mandated standard syllabus for the teaching of science and

history to all students in Years 7 to 10. There was a lack of studies that

measured variance in higher order instructional emphasis in a context with

such a constraint.

Research design

To investigate the relationship between teacher efficacy and higher order

instructional emphasis, the following research questions were identified:

What emphasis do teachers of history and science place on higher

order instructional objectives and outcomes for students in Year 7 to

Year 10?

Does the emphasis that teachers of history and science place on

higher order instructional objectives and outcomes change through

Year 7 to Year 10?

Does the emphasis that teachers of history and science place on

higher order instructional objectives and outcomes change with the

nature of the class?

To what extent is any variance in the emphasis placed on higher order

instructional objectives and outcomes explained by teacher efficacy?

The research design consisted of two stages. The first stage of the study

consisted of a pilot of the questionnaire to collect data on higher order

instructional emphasis in science and history and on teacher efficacy. The

questionnaire was piloted with 21 respondents.

The main part of the study involved the distribution of a questionnaire to a

random sample of 35 government high and central schools as well as semi-

structured interviews with seven teachers from four different schools.

The questionnaire consisted of background information on the respondents

and the junior classes reported on, a scale for the instructional emphasis of

junior classes and a scale for the measurement of teacher efficacy. Teachers

were requested to complete the instructional emphasis scale for two junior

classes. Background information requested of respondents consisted of sex,

years of teaching and years at the current school. Respondents were also

7

requested to indicate the year level of the class whether the class was graded

high, average or low achievement or was of mixed ability.

This study used the sixteen-item Gibson and Dembo (1984) Teacher Efficacy

Scale. This instrument has been widely used (e.g. Reames and Spencer,

1998; Yisrael, 1996; Hipp,1996), is reliable and is "recognised as a standard

measure of professional efficacy (Ghaith and Yaghi, 1997:453). The scale

has response options scored on a six-point Likert scale ranging from 1=

"strongly disagree to 6 = "strongly agree.

Use of the Gibson and Dembo (1984) Teacher Efficacy Scale allowed the

three factors of teacher efficacy: teaching efficacy; personal efficacy; and,

outcome efficacy to be examined. These three factors were considered in

terms of the extent to which they explained the higher order instructional

emphasis of teachers. Use of a three-factor or two-factor solution depended

on factor analyses of the teacher efficacy scale and the extent to which the

solution contributed to the central focus of the research on the relationship

between teacher efficacy and higher order instructional emphasis. The two

factors of teaching efficacy and personal efficacy were to be used if it was

found, as noted above with Woolfolk and Hoy (1990: 88), that analysis using

the three aspects of efficacy added nothing to analyses based on the two

independent factors of teaching efficacy and personal efficacy.

Separate measures of instructional emphasis for history and science were

developed. Measurement of instructional emphasis consisted of items that

measured higher order instructional emphasis and items that measured lower

order instructional emphasis as suggested by Raudenbush et al (1993:536).

The scale for each of history and science consisted of twenty items. Ten items

were designed to tap higher order instructional emphasis for each subject,

consistent with the advice by Raudenbush et al (1993:546). Ten items were

constructed to measure lower order instructional emphasis. A six-point Likert

scale was used ranging from 1 = "no emphasis to 6 = "very strong emphasis.

The construction of items to measure higher order instructional emphasis in

science and history involved mapping objectives and outcomes from the New

South Wales Board of Studies syllabuses for these subject areas to the

elements of higher order thinking in the literature so as to construct items that

were to be categorised as higher order. A similar process was used with the

lower order items.

Characteristics of the sampIe

Of the 85 teachers in the sample, 52 (61.2 per cent) were science teachers

and 33 (38.8 per cent) were history teachers. This was consistent with the

distribution of questionnaires with 60 per cent of the surveys for science

teachers and 40 per cent for history teachers.

Of the 85 teachers 47 (55.3 per cent) were male and 38 (44.7 per cent) were

female.

8

Teachers in the sample were highly experienced with mean years of

experience = 17.99 (SD = 8.06) and 54.1 per cent having nineteen or more

years of experience and 5.9 per cent having four years or fewer.

The teachers tended to have been at their current school for a substantial

period of time with mean years at current school = 7.98 (SD=5.82). 12.9 per

cent were in their first year at their current school.

The 85 teachers in the sample provided information on 161 classes.

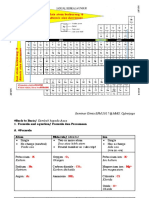

TabIe 1: Characteristics of science and history cIasses

ResuIts

InstructionaI ScaIes

Principal components factor analysis was performed on both the science and

history instruments. These analyses revealed two separate factors which

corresponded with higher order emphasis and lower order emphasis in each

of science and history. The separate higher order scales for science and

history were reliable with an alpha coefficient of .8914 for science and of

.8479 for history while the lower order scales were less reliable than the

respective higher order scales but still quite reliable with an alpha coefficient

of .7853 for science and .8479 for history.

The correlations between the higher order and lower order scales in science

and history were respectively .384 and -.177. On the science scale those

items measuring lower order emphasis did not load negatively on the higher

Science History Characteristic

Number Per Cent of

science

cIasses

Number Per Cent

of history

cIasses

Year 7

30 30.3 11 17.7

Year 8 20 20.2 10 16.1

Year 9 18 18.2 19 30.7

Year 10 26 26.3 20 32.3

Vertically integrated 5 5.1 2 3.2

mixed ability 40 40.4 35 56.5

low achievement 16 16.2 4 6.5

average achievement 13 13.2 7 9.7

high achievement 30 30.3 16 25.8

Total number of classes 99 100 62 100

9

order scale. This would suggest that higher order instructional emphasis does

not necessarily mean that a teacher would not also emphasise lower order

instructional objectives and outcomes. This would confirm Raudenbush,

Rowan and Cheong's suggestion (1993: 535). On the history scale, eight of

the ten lower order items loaded negatively on the higher order scale but the

weak correlation would not support a contention that teachers either

emphasised lower order instructional objectives and outcomes or higher order

instructional objectives and outcomes.

Descriptive statistics for higher order instructionaI emphasis

The mean for higher order instructional emphasis of 3.7 (SD 0.7) fell between

"some emphasis (3) and "moderate emphasis (4).

Changes in higher order instructional emphasis amongst each of the year

levels was then examined. The mean increased at each of Years 7 to 10 from

3.2 in Year 7 to 4.1in Year 10.

Figure 1 compares higher order instructional emphasis in science and history

through Years 7 to 10. Generally, a similar pattern was noted.

Higher order instructionaI emphasis for

science and history - year IeveIs

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

Year 7 Year 8 Year 9 Year 10

Science

History

Figure 1 Comparison of higher order emphasis in science and history by

year IeveI

The overall increase between Year 7 and Year 10 was substantial for both

science and history but the pattern of increase varied between the two

subjects. n science the largest change was between Year 8 and Year 9 while

in history there was virtually no change between Year 8 and Year 9 with the

largest change between Year 7 and Year 8. Table 2 displays the results.

10

TabIe 2: Changes in standard deviation units in higher order emphasis by

year IeveI

OveraII Science History

Year 7 to Year 8

.39 sd .16 sd .66 sd

Year 8 to Year 9 .24 sd .42 sd .05 sd

Year 9 to Year 10 .55 sd .28 sd .49 sd

TotaI change 1.18 sd .86 sd 1.20 sd

n relation to class types the means ranged from 3.05 for classes graded as

low achievement to 4.12 for classes graded as high achievement. This

corresponded to some emphasis (3) and to moderate emphasis (4).

Higher order instructionaI emphasis -

cIass type means

4.12

3.508

3.765

3.05

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

high mixed average low

Figure 2 Higher order instructionaI emphasis by cIass type

Teacher efficacy scaIe anaIysis

Both oblique and orthogonal rotations were used to compare a two factor and

three factor solution in concurrence with the theoretical models for teacher

efficacy as discussed above. A three-factor solution of teaching efficacy,

personal efficacy and outcome efficacy was not supported with only two of the

four items posited to be part of the factor of outcome efficacy loading on this

factor. The analysis was more supportive of a two-factor solution of teaching

efficacy and personal efficacy. A two-factor solution in this study explained

39.207 per cent of the total variance, more than the 28.2 per cent of total

11

variance explained by the Gibson and Dembo two-factor solution and the 30.7

per cent of the Soodak and Podell three-factor solution. The factors were only

weakly correlated (.173)

Analysis of internal consistency reliabilities yielded an alpha coefficient of

.6636.

The mean item scores for teaching efficacy were lower at 3.26 compared with

personal efficacy 4.38 on the six-point scale.

Results confirmed the independent nature of the factors underlying teacher

efficacy. t is possible that teachers could have one view of the ability of

teachers to overcome factors such as home environment and a separate view

of their own ability to produce the behaviours necessary to do so.

This sample of teachers demonstrated a stronger sense of personal efficacy

than of teaching efficacy. The item mean was higher for personal efficacy than

for teaching efficacy with the eight items with the highest mean all from the

personal efficacy dimension. This sense of personal efficacy covered both the

learning area and the behavioural area. For instance over 70 per cent of

respondents moderately or strongly agreed that they could accurately assess

whether an assignment was at the correct level of difficulty and over 43 per

cent moderately or strongly agreed that if a student masters a new concept

then it might be because they, the teacher, knew how to teach that concept.

The item with the highest mean and with over 83 per cent of respondents

moderately or strongly agreeing was being able to deal quickly with disruptive

and noisy students.

The items where respondents indicated the least strength in teacher efficacy

related to the capacity of teachers to overcome the background of students.

The two items with the lowest mean related to limitations over discipline.

ReIationship between teacher efficacy and higher order instructionaI

emphasis

n order to study the relationship between teacher efficacy and higher order

instructional emphasis multiple linear regression analysis was used. The

correlation matrix indicated that there were four variables significantly

correlated at the 0.01 level (2-tailed) with the dependent variable, higher order

instructional emphasis. These were teacher efficacy, the personal efficacy

factor of teacher efficacy, the year level of the class and the nature of the

class.

The concern in using both teacher efficacy and its factor of personal efficacy

was their high correlation (" =.635). This raised the problem of collinearity with

multiple linear regression. Given the importance of personal efficacy and to

avoid problems of collinearity it was decided to use the two factors of teaching

efficacy and personal efficacy rather than teacher efficacy.

12

Tables 3 and 4 summarise the model and change statistics for the addition of

each variable. The dependent variable was higher order instructional

emphasis. Table 5 presents the coefficients.

TabIe 3: ModeI summary

ModeI R R Square Adjusted R

Square

Std. Error of

the Estimate

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

.056

a

.366

b

.501

c

.511

d

.515

e

.517

f

.611

g

.003

.134

.251

.262

.265

.267

.374

-.003

.123

.237

.243

.241

.239

.345

9.45

8.84

8.24

8.21

8.22

8.23

7.64

a. Predictors: (Constant), gender

b. Predictors: (Constant), gender, class nature

c. Predictors: (Constant), gender, class nature, class level

d. Predictors: (Constant), gender, class nature, class level, years

experience

e. Predictors: (Constant), gender, class nature, class level, years

experience, years at the school

f. Predictors: (Constant), gender, class nature, class level, years

experience, years at the school, teaching efficacy

g. Predictors: (Constant), gender, class nature, class level, years

experience, years at the school, teaching efficacy, personal efficacy

TabIe 4: Change statistics

Change Statistics ModeI

R Square

Change

F Change df1 df2 Sig.F

Change

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

.003

.131

.117

.010

.004

.002

.106

.499

23.870

24.598

2.169

.769

.466

26.005

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

159

158

157

156

155

154

153

.481

.000

.000

.143

.382

.496

.000

13

TabIe 5: Coefficients

Unstandardized

Coefficients

Standard-

ized

Coefficients

ModeI

B Std.

Error

Beta

t

Sig.

(Constant)

gender

Class nature

Class level

Years experience

Years at school

Teaching efficacy

Personal efficacy

-.16.301

-1.291

3.565

2.419

-.111

-1.742E-02

6.645E-02

.641

7.264

1.332

.599

.495

.087

.118

.107

.126

-.068

.391

.321

-.094

-.011

.042

.335

-2.244

-.969

5.952

4.888

-1.273

-.148

.622

5.100

.026

.334

.000

.000

.205

.883

.535

.000

The proportion of the variation in higher order instructional emphasis

explained by the inclusion of all the variables is 34.5 per cent. The proportion

of variation of higher order instructional emphasis contributed by class nature

and class level is significant. The proportion of variation contributed by

teaching efficacy is not significant. However, the proportion of variation

contributed by personal efficacy is significant. The variables of gender, years

of experience and years at the school which were not significant in the

correlation matrix did not significantly contribute to the proportion of variation.

The multiple regression analysis suggests that class nature (beta = .391) is

the best predictor of higher order instructional emphasis. Class level also

appears to be important (beta = .321). When these two variables are included

in the equation along with gender, years of experience, years at school and

teaching efficacy, then personal efficacy is still important (beta = .335) with the

probability associated with the # value at less than 0.005. Teaching efficacy is

not important even before personal efficacy is added (beta = .050).

Interviews

The interview subjects' understanding of higher order thinking reflected the

study's definition and the subjects confirmed that the items on the higher

order instructional emphasis scales measured higher order instructional

objectives and outcomes.

From the comments of the subjects it was interpreted that they placed at least

some emphasis on higher order instructional objectives and outcomes but that

there was some difference amongst them in the extent of that emphasis.

There was general consensus that there was more higher order instructional

14

emphasis in Year 9 and 10 than in Year 7 and 8. Variation in emphasis was

explained by the subjects as arising also from the ability of the students in the

class. The ability of students to cope with an emphasis on higher order

thinking was linked to such factors as the literacy levels and the language and

cultural background of the students.

The interviews explored the subjects' sense of teacher efficacy, looking at

both teaching efficacy and personal efficacy. Comments by the interview

subjects indicated a range in strength in both teaching efficacy and personal

efficacy. nterpretation of the subjects' comments supported the notion of the

independent nature of the two factors of teaching efficacy and personal

efficacy, a strong relationship between teacher efficacy, in particular personal

efficacy, and emphasis on higher order instructional objectives and outcomes.

Discussion

This study considered a number of independent factors to explain the

variation in higher order instructional emphasis. This enabled a more

considered judgement to be made on the importance of the contribution of

teacher efficacy to variance in higher order instructional emphasis.

Using multiple linear regression analysis, this study found that while the

proportion of variation contributed by teaching efficacy was not significant, the

proportion contributed by personal efficacy was significant. Class nature and

class level also were statistically significant. The important finding for this

study is that even when class nature and class level were included in the

equation along with gender, years of experience, years at school and teaching

efficacy, then personal efficacy was still important.

The interview stage also supported the relationship between teacher efficacy

and higher order instructional emphasis with that relationship stronger for

personal efficacy than for teaching efficacy. The three interview subjects who

were regarded as having the strongest higher order instructional emphasis

were the three subjects who were categorised as having strong personal

efficacy.

This study identified the powerful link between personal efficacy and higher

order instructional emphasis. Teachers with a greater sense of personal

efficacy placed a greater emphasis on higher order instructional objectives

and outcomes than teachers with a lower sense of personal efficacy in similar

contexts of the year level of the class and the nature of the class. This finding

supports other studies (Saklofske et al., 1988; Soodak and Podell, 1993;

Smylie, 1988; Allinder, 1994) that have found that personal efficacy

consistently relates to important teacher behaviours.

The results of this study could also help to explain the substantial between-

teacher variance in emphasis on higher order instructional goals for science

and social studies that was found in the study by Raudenbush et al. (1993).

15

Application of Bandura's theory (1977) to this study suggested that teachers

who believed in the power of teaching to overcome the effects of such factors

as the background of students and were confident in their own teaching

abilities were more likely to have a greater academic focus in the classroom

and give more emphasis to higher order instructional objectives and

outcomes. This study found that it was teacher confidence in their own

teaching abilities that mattered and not a general belief in the power of

teaching. This supports other studies that have found that teaching efficacy

does not relate to teaching behaviours and outcomes but that personal

efficacy does (Saklofske et al.; 1988; Soodak and Podell; 1993).

Taking into account that it was the personal efficacy factor of teacher efficacy

that was found to be important, the findings were consistent with the

expectation that teachers who had higher teacher efficacy were more likely to

emphasise higher order instructional objectives and outcomes than teachers

with lower teacher efficacy. This was considered to be the case because

higher efficacy teachers have a greater belief in their ability to succeed.

Furthermore they were more likely to have had success with higher order

objectives and outcomes with students in the past because such teachers

would make greater efforts to achieve them, would persist in the face of

difficulties and were better able to cope emotionally with problems that arose.

The comments of interview subjects with high personal efficacy were

consistent with this reasoning. These subjects spoke of an emphasis on

higher order thinking as "it (has) always been my goal, that " the (student)

background doesn't stop me emphasising higher order thinking, that it is "just

a matter of finding the right avenue and that "if we stay within their comfort

zone there will be no progress towards a higher level of thought. Difficulties

with students were seen as something to overcome rather than a reason not

to emphasise higher order instructional objectives and outcomes. They also

spoke of past achievement, in particular nominating performances of their

students in the Higher School Certificate.

This study investigated the relationship between higher order instructional

emphasis and teacher efficacy at the individual teacher level. n the high

school context it would be instructive for research to expand to the subject

department level or school level. Research has examined the construct of

collective teacher efficacy (Goddard et al., 2000). This construct has been

defined as " the groups' shared belief in its conjoint capabilities to organize

and execute courses of action required to produce given levels of

attainments (Bandura, 1997:477) and there is some initial evidence that

collective teacher efficacy is positively associated with differences between

schools in student achievement (Goddard et al., 2000).

16

ConcIuding comment

n conclusion it would be appropriate to quote the words from one of the

interview subjects who was categorised as having a strong sense of personal

efficacy.

Every student was in fact given guess you would say complete

entitlement to the full range of outcomes and really to be fair think that

that is really the only way that we can go.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allinder, R.M. 1994. The relationship between efficacy and the instructional

practices of special education teachers and consultants. Teacher Education

and Special Education, 17, pp.86-95.

Ashton, P.T. and Webb, R. 1982. Teachers' sense of efficacy: Toward an

ecological model. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American

Educational research Association, New York.

Ashton, P.T. and Webb, R.B. 1986. Making a difference: Teacher's sense of

efficacy and student achievement. Longman, New York.

Bandura, A. 1977. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral

change. Psychological Review, 84, pp. 191-215.

Clements, D.H. 1991. Enhancement of creativity in computer environments.

American Educational Research Journal, 28, pp. 173-187.

Coladarci, Theodore. 1992. Teachers' sense of efficacy and commitment to

teaching. Journal of Experimental Education, 60(4), pp. 323-337.

Dembo, M.H., and Gibson, S. 1985. Teacher's sense of efficacy: An important

factor in school improvement. Elementary School Journal, 86, pp.173-184.

Doyle, K. 1983. Evaluating teaching. Lexington Books, Lexington, MA.

Edwards, John. 1995 Teaching thinking in schools: An overview. Unicorn,

Vol.21, No. 1 pp. 27-47.

Fuller, B., Wood, K., Rapoport,T. and Dornbusch,S.M. 1982. The

organizational context of individual efficacy. Review of educational research,

51 (1), pp.7-30.

Ghaith,G. and Yaghi, H. 1997. Relationships among experience, teacher

efficacy, and attitudes toward the implementation of instructional

Gibson,S. and Dembo, M.H. 1984. Teacher efficacy: A construct validation.

Journal of Educational Psychology, 76, pp.569-582.

17

Gist, M.E. and Mitchell, T.R. 1992. Self-Efficacy: A Theoretical Analysis of ts

Determinants and Malleability. Academy of Management Review, 17, (2),

pp.183-211.

Goddard, Roger D., Hoy, Wayne K. and Hoy Woolfolk, Anita. 2000. Collective

Teacher Efficacy: ts Meaning, Measure, and mpact on Student Achievement.

American Educational Research Journal Vol. 37, No. 2, pp. 479-507.

Guskey, T.R. 1988. Teacher efficacy, self-concept, and attitudes toward the

implementation of instructional innovation. Teaching and Teacher Education,

4, pp.63-69.

Guskey, Thomas R. and Passaro, Perry D. 1994. Teacher Efficacy: A Study

of Construct Dimensions. American Educational Research Journal, Fall,

Vol.31, No. 3, pp. 627-643.

Hargreaves, Andy and Earl, Lorna. 1990. Rights of passage: a review of

selected research about schooling in the transition years. Toronto, Ontario

Ministry of Education.

Hipp, Kristine A. 1996. Teacher Efficacy: nfluence of Principal Leadership

Behavior. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American

Educational Research Association.

Linn, M.C., Sloane, K.D. and Clancy, M.J. 1987. deal and actual outcomes

for precollege Pascal instruction. Journal of Research in Science Teaching,

24, pp.467-490.

Midgley,C., Feldlaufer,H., and Eccles,J.S. 1989. Changes in Teacher Efficacy

and Student Self- and Task-Related Beliefs in Mathematics During the

Transition to Junior High School. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81

(2),pp.247-258.

Peterson, P.L. 1988. Teaching for higher-order thinking in mathematics: The

challenge for the next decade. Perspectives on research on effective

mathematics teaching. Vol. 1 pp.2-26. Lawrence Earlbaum Associates,

Reston, VA.

Podell, D.M. and Soodak, L.C. 1993. Teacher efficacy and bias in special

education referrals. Journal of Educational Research, 86, pp. 247-253.

Raudenbush, S., Rowan, B. And Cheong, Y. 1992. Contextual effects on the

self-perceived efficacy of high school teachers. Sociology of Education, 65,

pp. 150-167.

Reames, Ellen H. and Spencer, Wiiliam A. 1998. The Relationship between

Middle School Culture and Teacher Efficacy and Commitment. Georgia

Ross, J.A. 1992. Teacher efficacy and the effect of coaching on student

achievement. Canadian Journal of Education, 17(1), pp. 51-65.

18

Saklofske, D.H., Michayluk, J.O. and Randhawa, B.S. 1988. Teachers'

efficacy and teaching behaviors. Psychological Reports, 63, pp.407-414.

Schunk, D. 1991. Self-Efficacy and Academic Motivation. Educational

Psychologist, 26, pp. 207-231.

Soodak, L.C. and Podell, D.M. 1993. Teacher efficacy and student problems

as factors in special education referral. Journal of Special Education, 27, pp.

66-81.

Stipek,D.J. 1993. Motivation to Learn. Allyn and Bacon, Boston.

Tschannen-Moran, Megan, Woolfolk Hoy, Anita, Hoy, Wayne K. Teacher

Efficacy: ts Meaning and Measure. 1998. Review of Educational Research,

Vol. 68, No. 2, pp.202-248.

Underbakke, Melva, Borg, Jean M. and Peterson, Donovan. 1993.

Researching and Developing the Knowledge Base for Teaching Higher Order

Thinking. Theory into Practice, Volume 32, Number 3, Summer, pp.138-146.

Woolfolk, A.E. and Hoy, W.K. 1990. Prospective teachers' sense of efficacy

and beliefs about control. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82, pp.81-91.

Yisrael, Rich. 1996. Extending the Concept and Assessment of Teacher

Efficacy. Educational and Psychological Measurement, v 56,n6 pp.1015-25.

Вам также может понравиться

- Physics Notes For SPM 2019 (Landscape)Документ11 страницPhysics Notes For SPM 2019 (Landscape)cyric wong100% (1)

- Module Chapter 3-Gravitation2020 PDFДокумент20 страницModule Chapter 3-Gravitation2020 PDFNoorleha Mohd Yusoff100% (1)

- SC Tg4 - Praktis - Jawapan PDFДокумент8 страницSC Tg4 - Praktis - Jawapan PDFNoorleha Mohd Yusoff60% (5)

- Seminar Kimia SPM Mmu 2017 CG Adura Jawapan Kertas 2 PDFДокумент48 страницSeminar Kimia SPM Mmu 2017 CG Adura Jawapan Kertas 2 PDFNoorleha Mohd YusoffОценок пока нет

- SPM 2019 - K1 aDiN PDFДокумент34 страницыSPM 2019 - K1 aDiN PDFNoorleha Mohd YusoffОценок пока нет

- The Relationship Between Novice and Experienced EFLДокумент14 страницThe Relationship Between Novice and Experienced EFLNoorleha Mohd YusoffОценок пока нет

- Modul Ulangkaji Form 4Документ69 страницModul Ulangkaji Form 4KHARTHIKA78% (9)

- Chemquest 2018 c03 2018 p1 Jawapan PDFДокумент2 страницыChemquest 2018 c03 2018 p1 Jawapan PDFNoorleha Mohd YusoffОценок пока нет

- MRSM 1 Fiz Trial 2016Документ47 страницMRSM 1 Fiz Trial 2016Noorleha Mohd YusoffОценок пока нет

- Science SPM Chapter 2 Paper 1Документ10 страницScience SPM Chapter 2 Paper 1Derrick ChingОценок пока нет

- Peta MindaДокумент57 страницPeta MindaZAZOLNIZAM BIN ZAKARIAОценок пока нет

- 2016 - BHG AДокумент21 страница2016 - BHG ANoorleha Mohd YusoffОценок пока нет

- Skema Kertas 3 Set 2Документ6 страницSkema Kertas 3 Set 2Noorleha Mohd YusoffОценок пока нет

- A Study of Secondary Science Teacher Efficacy and Level of ConstrДокумент205 страницA Study of Secondary Science Teacher Efficacy and Level of ConstrNoorleha Mohd YusoffОценок пока нет

- Changes in Preservice Teachers Self-EfficacyДокумент13 страницChanges in Preservice Teachers Self-EfficacyNoorleha Mohd YusoffОценок пока нет

- Changes in Preservice Teachers Self-EfficacyДокумент13 страницChanges in Preservice Teachers Self-EfficacyNoorleha Mohd YusoffОценок пока нет

- Science Teacher Efficacy, National BoardДокумент158 страницScience Teacher Efficacy, National BoardNoorleha Mohd YusoffОценок пока нет

- Improving Higher Order Thinking Skills Among Freshmen by Teaching Science Through InquiryДокумент8 страницImproving Higher Order Thinking Skills Among Freshmen by Teaching Science Through InquiryNoorleha Mohd YusoffОценок пока нет

- Skema Kertas 2 Set 2Документ10 страницSkema Kertas 2 Set 2Noorleha Mohd YusoffОценок пока нет

- How, Why, ExplainДокумент7 страницHow, Why, ExplainNoorleha Mohd YusoffОценок пока нет

- Fizik f4 k1 Akhir 06Документ23 страницыFizik f4 k1 Akhir 06Shasha WiniОценок пока нет

- A Study of Secondary Science Teacher Efficacy and Level of ConstrДокумент205 страницA Study of Secondary Science Teacher Efficacy and Level of ConstrNoorleha Mohd YusoffОценок пока нет

- Skema Kertas 3 Set 3Документ9 страницSkema Kertas 3 Set 3Noorleha Mohd YusoffОценок пока нет

- HOTs Question Bab 4 Kertas 1-JawapanДокумент1 страницаHOTs Question Bab 4 Kertas 1-JawapanNoorleha Mohd YusoffОценок пока нет

- IT Phy F5 Final Year (BL)Документ18 страницIT Phy F5 Final Year (BL)Noorleha Mohd YusoffОценок пока нет

- Bilag 13 GB 28 Progress On Questionnaire DevelopmentДокумент33 страницыBilag 13 GB 28 Progress On Questionnaire DevelopmentNoorleha Mohd YusoffОценок пока нет

- HOTs Question Bab 1 Kertas 1-JawapanДокумент1 страницаHOTs Question Bab 1 Kertas 1-JawapanNoorleha Mohd YusoffОценок пока нет

- Trends and Issues of Research On In-Service Needs Assessment of Science Teachers: Global Vs The Malaysian ContextДокумент2 страницыTrends and Issues of Research On In-Service Needs Assessment of Science Teachers: Global Vs The Malaysian ContextNoorleha Mohd YusoffОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (120)

- GRE Data and Analysis ProblemsДокумент2 страницыGRE Data and Analysis ProblemsGreg Mat67% (3)

- Mo Et Al. - 2020 - Institutions, Implementation, and Program EffectivenessДокумент10 страницMo Et Al. - 2020 - Institutions, Implementation, and Program EffectivenessMarkus ZhangОценок пока нет

- SOA Documents Actuary CredibilityДокумент175 страницSOA Documents Actuary Credibilitytayko177Оценок пока нет

- 1 Assessment Review - JANICEДокумент136 страниц1 Assessment Review - JANICEJENNELIE CALAQUIОценок пока нет

- Chapter # 07 (Six Sigma)Документ50 страницChapter # 07 (Six Sigma)Hassan TariqОценок пока нет

- LAS #3 (Statistics and Probability) PDFДокумент5 страницLAS #3 (Statistics and Probability) PDFKenneth Carl OsillosОценок пока нет

- Ambit - Strategy - Thematic - Ten Baggers 8 - A Relook at The Past For Progress - 28jan2019 PDFДокумент29 страницAmbit - Strategy - Thematic - Ten Baggers 8 - A Relook at The Past For Progress - 28jan2019 PDFAadi GalaОценок пока нет

- StatДокумент9 страницStatRupesh ThapaliyaОценок пока нет

- Suinn, 2001Документ4 страницыSuinn, 2001Mahbub SarkarОценок пока нет

- Aljohns ReviewerДокумент4 страницыAljohns Revieweraljohn_riveraОценок пока нет

- Comparative Analysis Between Lean, Six Sigma and Lean Six Sigma ConceptsДокумент13 страницComparative Analysis Between Lean, Six Sigma and Lean Six Sigma ConceptsAfad KhanОценок пока нет

- Free Response Sem 1 Rev KeyДокумент9 страницFree Response Sem 1 Rev KeyHell SpawnzОценок пока нет

- F X F X: Range: 84.5 - 54.5 30 Standard DeviationДокумент4 страницыF X F X: Range: 84.5 - 54.5 30 Standard DeviationJhon Carlo ArbolОценок пока нет

- Mathematics in The Moderm World OBTL AllДокумент16 страницMathematics in The Moderm World OBTL AllLeandro Villaruz BotalonОценок пока нет

- LAB Using Excel For Analyzing Chemistry DataДокумент12 страницLAB Using Excel For Analyzing Chemistry DatakcbijuОценок пока нет

- Comparative Analysis On Mutual Fund Scheme MBA ProjectДокумент83 страницыComparative Analysis On Mutual Fund Scheme MBA Projectvivek kumar100% (1)

- Umasekaranppt 150527120556 Lva1 App6892Документ88 страницUmasekaranppt 150527120556 Lva1 App689215_01_1977_anandОценок пока нет

- Risk and Returns Questions With AnswersДокумент11 страницRisk and Returns Questions With AnswersyoussefОценок пока нет

- Probability and StatisticsДокумент8 страницProbability and Statisticsjayanth143ramОценок пока нет

- Statistical SymbolsДокумент1 страницаStatistical SymbolsJaime Luis Estanislao Honrado100% (1)

- Chem 26.1 Lab Manual 2017 Edition (2019) PDFДокумент63 страницыChem 26.1 Lab Manual 2017 Edition (2019) PDFBea JacintoОценок пока нет

- Probability NotesДокумент44 страницыProbability NotesLavakumar Karne100% (3)

- SPTC 0203 Q3 FPFДокумент27 страницSPTC 0203 Q3 FPFLove the VibeОценок пока нет

- Further Statistics 1 Unit Test 7 Central Limit TheoremДокумент3 страницыFurther Statistics 1 Unit Test 7 Central Limit TheoremJade BARTONОценок пока нет

- RandomVariables ProbDistДокумент40 страницRandomVariables ProbDistAnkur SinhaОценок пока нет

- Case Study Focsa CristinaДокумент20 страницCase Study Focsa CristinaCristina FocsaОценок пока нет

- Chapter 1 Sampling and Sampling DistributionsДокумент50 страницChapter 1 Sampling and Sampling DistributionsNour ChaabouniОценок пока нет

- Blending The Best of Lean Production and Six SigmaДокумент12 страницBlending The Best of Lean Production and Six SigmaMansoor AliОценок пока нет

- WeightsДокумент4 страницыWeightsBhavikОценок пока нет

- Wipro Six SigmaДокумент27 страницWipro Six SigmaHarshi AgarwalОценок пока нет