Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Acute Osteomyelitis

Загружено:

Imran TaufikИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Acute Osteomyelitis

Загружено:

Imran TaufikАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

851

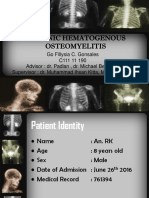

Case Report

A

cute hematogenous osteomyelitis in young chil-

dren occurs mostly in the metaphysis of a long

bone. Acute primary infection of the epiphysis is

uncommon.

(1)

Only a few cases of primary epiphy-

seal osteomyelitis have been reported,

(2-12)

because

delays in the diagnosis and treatment of an acute

hematogenous epiphyseal osteomyelitis are

common.

(8)

The interval between clinical presenta-

tion and diagnosis of epiphyseal osteomyelitis was

reported to be from 5 to 14 days.

(4,5,11)

A delay in

diagnosis of epiphyseal infection may allow the

infection to spread from the epiphysis into the knee

joint.

(4,5)

This, in turn, may lead to a sequelae of phy-

seal plate injury and joint surface destruction. We

reviewed 185 cases of acute septic arthritis and

hematogenous osteomyelitis in children during 12

years of clinical experience and found only 3 cases

with acute osteomyelitis of the distal femoral epiph-

ysis. Two patients, including one that was infected

by Salmonella enteritidis, were followed up for more

than 6 months.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

A 28-month-old boy was admitted to our hospi-

tal with a 7-day history of spiking fever and a 2-day

history of left knee pain and limping gait. Physical

examination revealed mild swelling, tenderness, and

local heat over the left knee. The left knee was kept

in flexion position, and the range of motion was 25-

70, being limited by pain.

Significant laboratory values on admission were

an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count of

10,400/cmm with a left shift and a C-reactive protein

(CRP) value of 94.7 mg/L. Initial radiographs

showed negative findings at the left knee, and blood

culture showed no organism. Empirical intravenous

oxacillin was given but the spiking fever still persist-

ed after 1 week. There was also progressive

swelling and fluid accumulation at the left knee. A

bone scan 1 week later revealed a mildly increased

uptake involving the lateral epiphysis of the left dis-

Acute Primary Hematogenous Osteomyelitis of the Epiphysis:

Report of Two Cases

Feng-Chen Kao, MD; Zhon-Liau Lee

1

, MD; Hui-Chih Kao

2

, MD;

Shuo-Suei Hung

3

, MD; Yhu-Chering Huang

4

, MD

Acute primary infection of the epiphysis is uncommon. We present 2 cases of acute

osteomyelitis of the distal femoral epiphysis. They were not diagnosed until 10 days and 3

weeks, respectively, after the onset of symptoms. The epiphyseal infection spread into the

knee joint, and surgical debridement was performed. The majority of reported cases in the

medical literature are of bacterial etiology, and the most common pathogen is

Staphylococcus aureus. We report a rare case which was infected by Salmonella enteritidis.

Prompt diagnosis and early treatment are required to prevent further destruction and growth

disturbance. (Chang Gung Med J 2003;26:851-6)

Key words: epiphysis, osteomyelitis.

From the Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Keelung;

1

Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Chang

Gung Memorial Hospital, Taoyuan;

2

Li-Shin Hospital, Taoyuan;

3

St. Paul Hospital, Taoyuan;

4

Division of Pediatric Infectious

Diseases, Chang Gung Children's Hospital, Taoyuan.

Received: Sep. 4, 2002; Accepted: Apr. 22, 2003

Address for reprints: Dr. Zhon-Liau Lee, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital. 5, Fushing Street,

Gueishan Shiang, Taoyuan, Taiwan 333, R.O.C. Tel.: 886-3-3281200 ext. 2420; Fax: 886-3-3278113

Chang Gung Med J Vol. 26 No. 11

November 2003

Feng-Chen Kao, et al

Osteomyelitis of the epiphysis

852

tal femur. Repeat radiographs (Fig. 1A, B) 10 days

later showed osteopenic lesions in the lateral epiph-

ysis of the left distal femur. Arthrocentesis was per-

formed, and culture of the synovial fluid showed no

organism. The antibiotics were shifted to van-

comycin and gentamicin, but the symptoms did not

improve. The repeat WBC count was 13,900/cmm,

and the CRP was 88.1 mg/L on day 20 after admis-

sion. The patient underwent a lateral arthrotomy to

approach the distal femoral epiphysis under fluo-

roscopy. The lytic area of the epiphysis was curetted

and irrigated.

Tissue culture obtained during surgery grew

Salmonella enteritidis. Ceftizoxime was given and

continued for 5 weeks. The patient became afebrile

by the 13th postoperative day. The knee was splint-

ed for 3 weeks, then range-of-motion exercises were

begun. Five weeks after the operation, the WBC

count was 6700/cmm, and the CRP was < 2 mg/L.

Ten months after the operation, radiographs showed

a 0.8`0.7-cm lytic lesion in the epiphysis. Sixteen

months after the operation, radiographs (Fig. 1C, D)

showed remodeling of the epiphysis and no physeal

growth arrest. The patient was able to walk normal-

ly, and the range of motion of the left knee was 0 to

120.

Case 2

A 27-month-old girl was transferred to our hos-

pital from a local medical hospital with persistent

tenderness and swelling of the right knee. She had

been admitted to that local medical hospital 2 months

previous under the impression of mycoplasma pneu-

monia and reactive arthritis of the left knee. Three

days later, the symptoms of the left knee had

resolved, but tenderness and limited range of motion

of the right knee began.

Significant laboratory values were an elevated

WBC count (14,600/cmm) and an erythrocyte sedi-

mentation rate (ESR) of 105 mm/h. The CRP level

was 3.25 mg/L. Blood culture upon admission grew

Staphylococcus aureus, but the culture of the syn-

ovial fluid showed no growth of organism.

The Ga-67 citrate scan showed increased uptake

in the right distal femur and right knee joint. The

radiographs (Fig. 2A, B) 3 weeks later showed main

changes of radiolucency, fragmentation, and a cres-

centic margin in the epiphysis of the right distal

femur. Surgical procedures including an arthrotomy

and curettage of the lytic areas of the distal femur

were performed and were followed with a course of

intravenous vancomycin for 6 weeks. Because ten-

derness and swelling of the right knee persisted and

the repeat ESR was 113 mm/h, she was transferred to

our hospital for further management.

At admission, her body temperature was 38C.

Physical examination revealed tenderness, swelling,

and erythematous change of the right knee area. The

Fig. 1 Case 1 (left knee). The repeat AP (A) and lateral (B) radiographs 10 days after onset of the disease showed radiolucency in

the lateral aspect of the right distal femoral epiphysis. AP (C) and lateral (D) radiographs 16 months after the operation showed

remodeling of the epiphysis and no physeal growth arrest.

A B

C D

Chang Gung Med J Vol. 26 No. 11

November 2003

Feng-Chen Kao, et al

Osteomyelitis of the epiphysis

853

right knee was kept in flexion position, and the range

of motion was 30-110, being limited by pain. The

WBC count was 12,200/cmm, and the CRP was 21.4

mg/L. The following radiographs (Fig. 2C, D)

showed progressive osteopenic lesions with some

sclerotic changes and fragmentation at the right dis-

tal femoral epiphysis. Repeated aspiration and blood

cultures produced no growth.

Under a diagnosis of epiphyseal osteomyelitis of

the right distal femur and poor clinical response to

vancomycin by the Staphylococcus aureus infection,

intravenous teicoplanin was given for 4 weeks. The

patient became afebrile 3 days later. Surgery was

deferred because of the good clinical response to the

intravenous antibiotics. The swelling and tenderness

of the right knee improved with time. After dis-

charge, full range of motion without weight bearing

was achieved at the 6-month follow-up.

DISCUSSION

An acute primary infection of the epiphysis is

uncommon.

(1)

Infections isolated to the epiphysis

predominantly occur around the knee. Sorensen

(2)

reviewed 21 cases of primary epiphyseal

osteomyelitis and found that 20 involved the epiph-

ysis of the distal femur or proximal tibia. The distal

femoral epiphysis has been involved in up to 75% of

cases of epiphyseal infection.

(6)

Our 2 cases both

involved the distal femoral epiphysis. We reviewed

185 cases of acute septic arthritis and hematogenous

osteomyelitis in children in our 12 years of clinical

experience and found only 3 cases of epiphyseal

osteomyelitis.

Epiphyseal osteomyelitis may present in either

an acute or subacute form. The acute form is charac-

terized by rapid onset and progression.

(4,5,8)

Local

symptoms of tenderness and limping are often

accompanied by systemic signs. Leukocytosis and

elevated ESR are usually noted. Radiographs may

be normal early in the course of the disease, but a

lytic lesion in the epiphysis will present at a later

stage. The subacute form is insidious at onset.

(3,6)

It

is characterized by mild pain localized to the infected

area, and symptoms are often exacerbated by activi-

ty. There are usually no systemic symptoms.

Laboratory examinations are also often normal, and

radiographs reveal a well-demarcated lytic lesion.

(6)

Factors, such as increased host resistance, decreased

bacterial virulence, or antibiotics given during the

pre-symptomatic period, may alter the clinical pic-

ture towards a subacute form.

(5,8)

Most cases of pri-

mary epiphyseal osteomyelitis are reported in the

subacute form.

(3,6)

According to Longjohn,

(5)

only 5

cases of acute hematogenous osteomyelitis of the

epiphysis have been reported.

(4,5,8,11)

Our 2 cases are

also of the acute form of osteomyelitis.

In the newborn, before the secondary centers of

Fig. 2 Case 2 (right knee). The AP (A) and lateral (B) radiographs 3 weeks after presentation showed radiolucency, fragmentation,

and a crescentic margin of the lesion in the right distal femoral epiphysis. AP (C) and lateral (D) radiographs 2 weeks after the oper-

ation showed osteopenic lesions with some surrounding sclerotic change at the right distal femoral epiphysis.

A B

C D

Chang Gung Med J Vol. 26 No. 11

November 2003

Feng-Chen Kao, et al

Osteomyelitis of the epiphysis

854

ossification appear, the transphyseal vessels persist

until 15 to 18 months of age.

(9,10)

After this age, the

physis provides a mechanical barrier to protect

against the spread of infection. Brooks

(13)

and

Trueta

(10)

tried to explain the pathophysiology of epi-

physeal infection. The blood enters the epiphysis via

epiphyseal arteries and is then carried to the surfaces

of the articular and physeal cartilage via Hunter's cir-

cle. This forms a loop of branching arcades which

anastomose with veins. Changes in the diameter of

the vessels result in sludging of the blood, which is

responsible for the epiphyseal infection.

(4-6,12)

The

majority of reported cases are bacterial with the most

common pathogen being Staphylococcus aureus.

(2-8)

Streptococcus pneumoniae,

(3,7)

Haemophilus influen-

zae,

(2)

Kingella kingae,

(14)

and fungal infection

(15)

have

also been identified. We report a rare case (case 1)

which was infected by Salmonella enteritidis. A

review of the literature demonstrated only 12 cases

of Salmonella osteomyelitis in children who did not

have sickle cell disease.

(16,17)

Diagnosis of acute hematogenous epiphyseal

osteomyelitis is often based on serial radiographic

finding and is confirmed by positive culture at the

lesion site. Making a diagnosis is often delayed.

(8)

The time from presentation of symptoms to diagno-

sis of epiphyseal osteomyelitis is usually between 5

and 14 days.

(4,5,11)

The initial radiographs usually

show negative finding

(4,5,8)

and the repeat radiographs

(at 10 to 21 days later) show lytic lesions of the epi-

physis. A bone scan and gallium scan are often nec-

essary, because the radiographic changes detected in

acute hematogenous osteomyelitis may only be about

20% at 10 to 14 days after the onset of illness.

(18)

A

bone scan may confirm the diagnosis as early as 24

to 48 hours after the onset of clinical illness.

(19)

The

bone scan reflects increased bone mineral turnover in

general, and not specifically infection. Gallium

uptake exceeds that seen on the bone scan, and

incongruence of the spatial distribution of gallium

and bone uptake are considered reliable indicators of

osteomyelitis.

(20)

Therefore, combined bone/gallium

scintigraphy is helpful when there is poor localiza-

tion of the clinical findings.

The clinical manifestations of epiphyseal

osteomyelitis are similar to those of a septic knee.

The difference between them is that epiphyseal

osteomyelitis involves only the femoral or tibial epi-

physis, while septic knee involves both. The differ-

ential diagnosis is based on radiographic and

bone/gallium scan findings in the early stage.

A delay in diagnosing epiphyseal infection may

allow the infection to spread from the epiphysis into

the knee joint.

(4,5)

Our 2 cases similarly had a septic

knee which required surgical debridement. So,

aggressive intravenous antibiotic therapy is needed at

an early stage, which may prevent the spread of the

infection to adjacent joints if the clinical response is

good.

(5,8)

The antibiotic regimen is based on bacterial

sensitivities, the clinical response, and subsequent

ESR/CRP levels. A 4- to 6-week course of parenter-

al antibiotics is usually needed. Surgical interven-

tion may be indicated when there are 1) progression

on radiographic findings, 2) poor clinical response to

conservative treatment with intravenous antibiotics,

and 3) concomitant septic arthritis. Although no

growth disturbances have been reported, observing

these children to skeletal maturity is recommended.

(5)

In conclusion, increased awareness of acute epi-

physeal osteomyelitis is necessary to obtain an early

diagnosis. Repeat radiographs 10 days after the

onset of illness, bone scan, and Ga-67 inflammatory

scan are recommended for diagnosis. Treatment

should consist of proper antibiotics and surgery

depending on the clinical course.

REFERENCES

1. Green NE. Osteomyelitis of the epiphysis. In: Uhthoff

HK, Wiley JJ eds. Behavior of the Growth Plate. New

York: Raven Press 1988;323-9.

2. Sorensen TS, Hedeboe J, Christensen ER. Primary epi-

physeal osteomyelitis in children. Report of three cases

and review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1988;

70:818-20.

3. Andrew TA, Porter K. Primary subacute epiphyseal

osteomyelitis: a report of three cases. J Pediatr Orthop

1985;5:155-7.

4. Kramer SJ, Post J, Sussman M. Acute hematogenous

osteomyelitis of the epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop 1986;

6:493-5.

5. Longjohn DB, Zionts LE, Stott NS. Acute hematogenous

osteomyelitis of the epiphysis. Clin Orthop 1995;316:227-

34.

6. Green NE, Beauchamp RD, Griffin PP. Primary subacute

epiphyseal osteomyelitis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1981;

63:107-14.

7. Azouz EM, Greenspan A, Marton D. CT evaluation of

primary epiphyseal bone abscesses. Skeletal Radiol

1993;22:17-23.

8. Gibson WK, Bartosh R, Timperlake R. Acute hematoge-

Chang Gung Med J Vol. 26 No. 11

November 2003

Feng-Chen Kao, et al

Osteomyelitis of the epiphysis

855

nous epiphyseal osteomyelitis. Orthopedics 1991;14:705-

7.

9. Ogden JA, Lister G. The pathology of neonatal

osteomyelitis. Pediatrics 1975;55:474-8.

10. Trueta J. The three types of acute hematogenous

osteomyelitis: A clinical and vascular study. J Bone Joint

Surg Br 1959.41:671-80.

11. Maffulli N, Fixsen JA. Osteomyelitis of the proximal

radial epiphysis: A case report. Acta Orthop Scand 1990;

61:269-70.

12. Rosenbaum DM, Blumhagen JD. Acute epiphyseal

osteomyelitis in children. Radiology 1985;156:89-92.

13. Brooks M. The Blood Supply of Bone. New York, NY:

Appleton-Century Crofts 1971.

14. Shelton MM, Nachtigal MP, Yngve DA, Herndon WA,

Riley HD Jr. Kingella kingae osteomyelitis: report of two

cases involving the epiphysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1988;

7:421-4.

15. Nissen TP, Lehman CR, Otsuka NY, Cerruti DM. Fungal

osteomyelitis of the distal femoral epiphysis. Orthopedics

2001;24:1083-4.

16. Ebrahim GJ, Grech P. Salmonella osteomyelitis in infants.

J Bone Joint Surg Br 1996;48:350-53.

17. Sucato DJ, Gillespie R. Salmonella pelvic osteomyelitis

in normal children: report of two cases and a review of

the literature. J Pediatr Orthop 1997;17:463-6.

18. Morrey BF, Peterson HA. Hematogenous pyogenic

osteomyelitis in children. Orthop Clin North Am 1975;

6:935-51.

19. Nelson JD. The bacterial etiology and medical manage-

ment of septic arthritis in infants and children. Pediatrics

1972;50:437-40.

20. Lewis JS, Rosenfeld NS, Hoffer PB, Downing D. Acute

osteomyelitis in children, combined Tc-99m and Ga-67

imaging. Radiology 1986;158:795-804.

856

)|jjj ]jh [|

1

jh [|

2

])jj

3

]|jj

4

)|jj jh |

,))[919)4]]])[924)22

,||H/_j])|jjj [|j333j#j[]5Tel.: (03)3281200]2420; Fax: (03)

3278113

(epiphysis)

1 2 3 4

2 2

10 21

()|j2003;26:851-6)

Вам также может понравиться

- Anti-Neutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody (ANCA) Associated VasculitisОт EverandAnti-Neutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody (ANCA) Associated VasculitisRenato Alberto SinicoОценок пока нет

- Septic Arthritis in MalignancyДокумент4 страницыSeptic Arthritis in MalignancyEBNY MOBA & PUBG Mobile GamingОценок пока нет

- Case Report: Zehava Sadka Rosenberg, 1 Steven Shankman, 1 Michael Klein, 2'3 and Wallace Lehman4Документ3 страницыCase Report: Zehava Sadka Rosenberg, 1 Steven Shankman, 1 Michael Klein, 2'3 and Wallace Lehman4Mohamed Ali Al-BuflasaОценок пока нет

- Annrheumd00265 0070Документ7 страницAnnrheumd00265 0070Ravi KiranОценок пока нет

- Brucellosis and Is A Coomon Ion of Uncommon PathogenДокумент7 страницBrucellosis and Is A Coomon Ion of Uncommon PathogenSohail FazalОценок пока нет

- International Journal of Surgery Case ReportsДокумент4 страницыInternational Journal of Surgery Case Reportshussein_faourОценок пока нет

- Case Report: Osteomyelitis of The Patella in A 10-Year-Old Girl: A Case Report and Review of The LiteratureДокумент6 страницCase Report: Osteomyelitis of The Patella in A 10-Year-Old Girl: A Case Report and Review of The LiteratureIfal JakОценок пока нет

- 83-Article Text-163-1-10-20180209Документ4 страницы83-Article Text-163-1-10-20180209Grace Meigawati IwantoОценок пока нет

- Chronic Hematogenous OsteomyelitisДокумент45 страницChronic Hematogenous OsteomyelitisNur Jannah NasirОценок пока нет

- Rhizomucor Scedosporium: Case ReportДокумент6 страницRhizomucor Scedosporium: Case ReportPaul ColburnОценок пока нет

- Case StudyДокумент6 страницCase Study2qmdjr2qhkОценок пока нет

- ACR EducationДокумент53 страницыACR EducationamereОценок пока нет

- 1 s2.0 S1607551X09702748 MainДокумент6 страниц1 s2.0 S1607551X09702748 MainAbdul RaufОценок пока нет

- Junal PyodermaДокумент6 страницJunal PyodermaJares Clinton Saragih SimarmataОценок пока нет

- A Rare Cause of Endocarditis: Streptococcus PyogenesДокумент3 страницыA Rare Cause of Endocarditis: Streptococcus PyogenesYusuf BrilliantОценок пока нет

- Revoke SuretyДокумент3 страницыRevoke Suretysonya.rylee99Оценок пока нет

- Jurnal THTДокумент5 страницJurnal THTTri RominiОценок пока нет

- SJMCR-57438-440Документ3 страницыSJMCR-57438-440Dwi PascawitasariОценок пока нет

- Case On Ankle SurgeryДокумент13 страницCase On Ankle SurgeryLuqman AhmedОценок пока нет

- Ajr 127 5 789Документ4 страницыAjr 127 5 789Egi Patnialdi Firda PermanaОценок пока нет

- Ovadia 2007Документ7 страницOvadia 2007uditОценок пока нет

- Caso ClinicoДокумент3 страницыCaso ClinicoSamyОценок пока нет

- Case 5-2009: A 47-Year-Old Woman With A Rash and Numbness and Pain in The LegsДокумент10 страницCase 5-2009: A 47-Year-Old Woman With A Rash and Numbness and Pain in The LegsRommel D-pОценок пока нет

- Transient SynovitisДокумент9 страницTransient SynovitisMuhammad Taufik AdhyatmaОценок пока нет

- Delay in Diagnosis of Extra-Pulmonary Tuberculosis by Its Rare Manifestations: A Case ReportДокумент5 страницDelay in Diagnosis of Extra-Pulmonary Tuberculosis by Its Rare Manifestations: A Case ReportSneeze LouderОценок пока нет

- Pathological Unstable Dislocation of Shoulder S 2024 International Journal oДокумент5 страницPathological Unstable Dislocation of Shoulder S 2024 International Journal oRonald QuezadaОценок пока нет

- Toorthj 6 445Документ4 страницыToorthj 6 445Sonia RogersОценок пока нет

- Case Study 3 - Knee PainДокумент12 страницCase Study 3 - Knee PainElizabeth Ho100% (9)

- MedicalДокумент29 страницMedicalZia Ur RehmanОценок пока нет

- Tuberculous Coxitis: Diagnostic Problems and Varieties of Treatment: A Case ReportДокумент4 страницыTuberculous Coxitis: Diagnostic Problems and Varieties of Treatment: A Case Reportnur afrinda mulyaОценок пока нет

- Arthroscopic Treatment of Acute Septic Arthritis After Meniscal Allograft TransplantationДокумент4 страницыArthroscopic Treatment of Acute Septic Arthritis After Meniscal Allograft TransplantationserubimОценок пока нет

- Lupus SeverДокумент3 страницыLupus SeverdeliaОценок пока нет

- Art 1780310221Документ4 страницыArt 1780310221Leonardo BarrosoОценок пока нет

- Case ReportДокумент14 страницCase ReportdivaОценок пока нет

- Primary Aortoenteric FistulaДокумент5 страницPrimary Aortoenteric FistulaKintrili AthinaОценок пока нет

- A Case Report Calcific Piriformis Tendinitis in A Patient With Known SarcoidosisДокумент4 страницыA Case Report Calcific Piriformis Tendinitis in A Patient With Known SarcoidosisAthenaeum Scientific PublishersОценок пока нет

- Gonitis TranslateДокумент8 страницGonitis TranslateYessica DestianaОценок пока нет

- Journal of Orthopaedics, Trauma and Rehabilitation: Case ReportДокумент2 страницыJournal of Orthopaedics, Trauma and Rehabilitation: Case ReportStephanie HellenОценок пока нет

- Dengue With Spinal Cord HematomaДокумент3 страницыDengue With Spinal Cord HematomaAshwaq TpОценок пока нет

- Knots and Knives - 3rd EditionsДокумент4 страницыKnots and Knives - 3rd EditionsNasser AlbaddaiОценок пока нет

- Case 17: 4-Year-Old Refusing To Walk-EmilyДокумент6 страницCase 17: 4-Year-Old Refusing To Walk-Emilyarlene-bury-fiol-6287Оценок пока нет

- Yersinia Enterocolitica: A Rare Cause of Infective EndocarditisДокумент3 страницыYersinia Enterocolitica: A Rare Cause of Infective EndocarditisDIEGO FERNANDO TULCAN SILVAОценок пока нет

- A Neonatal Septic Arthritis Case Caused by Klebsiella Pneumoniae - A Case ReportДокумент2 страницыA Neonatal Septic Arthritis Case Caused by Klebsiella Pneumoniae - A Case Reportkartini ciatawiОценок пока нет

- Stevens-Johnson Syndrome Without Skin Lesions: Case ReportДокумент4 страницыStevens-Johnson Syndrome Without Skin Lesions: Case ReportYona LadyventiniОценок пока нет

- Disseminated Tuberculous Myositis in A Child With Acut 2009 Pediatrics NeoДокумент4 страницыDisseminated Tuberculous Myositis in A Child With Acut 2009 Pediatrics NeoFrankenstein MelancholyОценок пока нет

- Path Block 3 PresentДокумент14 страницPath Block 3 PresentshevyОценок пока нет

- Pediatric Round PneumoniaДокумент4 страницыPediatric Round PneumoniaSalwa Zahra TsamaraОценок пока нет

- Granulomatose Eosinophilique Avec Polyangeite: Presentations Inhabituelles. Eosinophilic Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis: Unusual PresentationsДокумент5 страницGranulomatose Eosinophilique Avec Polyangeite: Presentations Inhabituelles. Eosinophilic Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis: Unusual PresentationsIJAR JOURNALОценок пока нет

- Inbound 988634411507331531Документ7 страницInbound 988634411507331531Jeannelle Landiza AmeninОценок пока нет

- Septic Arthritis UpgradedДокумент47 страницSeptic Arthritis UpgradedVishva Randhara AllesОценок пока нет

- Tuberculosis of Talus A Case ReportДокумент4 страницыTuberculosis of Talus A Case ReportPutra DariusОценок пока нет

- The Challenge of Diagnosing Psoas Abscess: Case ReportДокумент4 страницыThe Challenge of Diagnosing Psoas Abscess: Case ReportNataliaMaedyОценок пока нет

- Case Report: Vertigo As A Predominant Manifestation of NeurosarcoidosisДокумент5 страницCase Report: Vertigo As A Predominant Manifestation of NeurosarcoidosisDjumadi AkbarОценок пока нет

- Leg Tuberculosis Presenting As Hypopion UveitisДокумент3 страницыLeg Tuberculosis Presenting As Hypopion UveitisIJAR JOURNALОценок пока нет

- Spinal Epidural Abscess in Two CalvesДокумент8 страницSpinal Epidural Abscess in Two CalvesRachel AutranОценок пока нет

- Peptostreptococcus Asaccharolyticus: 2001 107 E11 Veronica A. Mas Casullo, Edward Bottone and Betsy C. HeroldДокумент6 страницPeptostreptococcus Asaccharolyticus: 2001 107 E11 Veronica A. Mas Casullo, Edward Bottone and Betsy C. HeroldCarolina Cabrera CernaОценок пока нет

- 51 Sumantro EtalДокумент3 страницы51 Sumantro EtaleditorijmrhsОценок пока нет

- Surgical Case Presentation On: Presented By: Mrs - Anisha ManeДокумент35 страницSurgical Case Presentation On: Presented By: Mrs - Anisha ManeAnisha Mane100% (1)

- Running Head: CASE STUDY PAPER 1Документ14 страницRunning Head: CASE STUDY PAPER 1Issaiah Nicolle CeciliaОценок пока нет

- Necrotising Myositis - A Surgical Emergency That May Have Minimal Changes in The SkinДокумент3 страницыNecrotising Myositis - A Surgical Emergency That May Have Minimal Changes in The SkinDaniel R.SОценок пока нет

- Patch Testing PDFДокумент18 страницPatch Testing PDFImran TaufikОценок пока нет

- Obat GastroДокумент16 страницObat GastroImran TaufikОценок пока нет

- Osteomyelitis Acut Dan Kronik JournalДокумент33 страницыOsteomyelitis Acut Dan Kronik JournalImran TaufikОценок пока нет

- JNC8Документ14 страницJNC8Syukron FadillahОценок пока нет

- Herpes ZosterДокумент20 страницHerpes ZosterDiamond DustОценок пока нет

- The ShoulderДокумент26 страницThe ShoulderImran TaufikОценок пока нет

- Middle East Fertility Society Journal EndometriumДокумент22 страницыMiddle East Fertility Society Journal EndometriumImran TaufikОценок пока нет

- JNC8Документ14 страницJNC8Syukron FadillahОценок пока нет

- V Siklus Menstruasi Normal JLH V Perubahan Fisik Setelah Menarche JLH VДокумент12 страницV Siklus Menstruasi Normal JLH V Perubahan Fisik Setelah Menarche JLH VImran TaufikОценок пока нет

- Sal Bio1Документ13 страницSal Bio1Imran TaufikОценок пока нет

- Presentation 1Документ2 страницыPresentation 1Imran TaufikОценок пока нет

- Foreign Body AirwayДокумент26 страницForeign Body AirwayImran TaufikОценок пока нет

- Kelainan MenstruasiДокумент7 страницKelainan MenstruasiImran TaufikОценок пока нет

- D10 AnatomyДокумент16 страницD10 AnatomyNiladri DasОценок пока нет

- Acute OsteomyelitisДокумент6 страницAcute OsteomyelitisImran TaufikОценок пока нет

- Pediatric NotesДокумент41 страницаPediatric NotesImran TaufikОценок пока нет

- Female Reproduction: ANSC 1000 Introductory Animal ScienceДокумент17 страницFemale Reproduction: ANSC 1000 Introductory Animal ScienceImran TaufikОценок пока нет

- Referensi Osteomyelitits Akut Dan KronikДокумент13 страницReferensi Osteomyelitits Akut Dan KronikHasnaAlimuddinОценок пока нет

- Female Reproduction: ANSC 1000 Introductory Animal ScienceДокумент17 страницFemale Reproduction: ANSC 1000 Introductory Animal ScienceImran TaufikОценок пока нет

- Acute OsteomyelitisДокумент6 страницAcute OsteomyelitisImran TaufikОценок пока нет

- Referensi Osteomyelitis Buku David Sutton and Paul Joul.Документ4 страницыReferensi Osteomyelitis Buku David Sutton and Paul Joul.Imran TaufikОценок пока нет

- Reproductive Biology (Histological & Ultrastructure) and Biochemical Studies in Ovaries of Mugil Cephalus From Mediterranean WaterДокумент26 страницReproductive Biology (Histological & Ultrastructure) and Biochemical Studies in Ovaries of Mugil Cephalus From Mediterranean WaterImran TaufikОценок пока нет

- Female Reproduction: ANSC 1000 Introductory Animal ScienceДокумент17 страницFemale Reproduction: ANSC 1000 Introductory Animal ScienceImran TaufikОценок пока нет

- Female Reproduction: ANSC 1000 Introductory Animal ScienceДокумент17 страницFemale Reproduction: ANSC 1000 Introductory Animal ScienceImran TaufikОценок пока нет

- GMBRДокумент5 страницGMBRImran TaufikОценок пока нет

- D7 DM CДокумент2 страницыD7 DM CImran TaufikОценок пока нет

- Kelainan MenstruasiДокумент7 страницKelainan MenstruasiImran TaufikОценок пока нет

- What You Need To Know About Your Drive TestДокумент12 страницWhat You Need To Know About Your Drive TestMorley MuseОценок пока нет

- Drager Narkomed 6400 Field Service Procedure Software Version 4.02 EnhancementДокумент24 страницыDrager Narkomed 6400 Field Service Procedure Software Version 4.02 EnhancementAmirОценок пока нет

- Pedagogy MCQS 03Документ54 страницыPedagogy MCQS 03Nawab Ali MalikОценок пока нет

- Daewoo 710B PDFДокумент59 страницDaewoo 710B PDFbgmentОценок пока нет

- Clint Freeman ResumeДокумент2 страницыClint Freeman ResumeClint Tiberius FreemanОценок пока нет

- Final Test Level 7 New Format 2019Документ3 страницыFinal Test Level 7 New Format 2019fabian serranoОценок пока нет

- Working Capital Management 2012 of HINDALCO INDUSTRIES LTD.Документ98 страницWorking Capital Management 2012 of HINDALCO INDUSTRIES LTD.Pratyush Dubey100% (1)

- Cipet Bhubaneswar Skill Development CoursesДокумент1 страницаCipet Bhubaneswar Skill Development CoursesDivakar PanigrahiОценок пока нет

- Unit 2 - Industrial Engineering & Ergonomics - WWW - Rgpvnotes.inДокумент15 страницUnit 2 - Industrial Engineering & Ergonomics - WWW - Rgpvnotes.inSACHIN HANAGALОценок пока нет

- Quanta To QuarksДокумент32 страницыQuanta To QuarksDaniel Bu100% (5)

- Lab Manual Switchgear and Protection SapДокумент46 страницLab Manual Switchgear and Protection SapYash MaheshwariОценок пока нет

- Lightning Protection Measures NewДокумент9 страницLightning Protection Measures NewjithishОценок пока нет

- 2023 Teacher Email ListДокумент5 страниц2023 Teacher Email ListmunazamfbsОценок пока нет

- Consent Form: Republic of The Philippines Province of - Municipality ofДокумент1 страницаConsent Form: Republic of The Philippines Province of - Municipality ofLucette Legaspi EstrellaОценок пока нет

- Vygotsky EssayДокумент3 страницыVygotsky Essayapi-526165635Оценок пока нет

- Enrile v. SalazarДокумент26 страницEnrile v. SalazarMaria Aerial AbawagОценок пока нет

- Liquitex Soft Body BookletДокумент12 страницLiquitex Soft Body Booklethello belloОценок пока нет

- Soundarya Lahari Yantras Part 6Документ6 страницSoundarya Lahari Yantras Part 6Sushanth Harsha100% (1)

- Low Speed Aerators PDFДокумент13 страницLow Speed Aerators PDFDgk RajuОценок пока нет

- Rotating Equipment & ServiceДокумент12 страницRotating Equipment & Servicenurkasih119Оценок пока нет

- Test Bank For The Psychology of Health and Health Care A Canadian Perspective 5th EditionДокумент36 страницTest Bank For The Psychology of Health and Health Care A Canadian Perspective 5th Editionload.notablewp0oz100% (37)

- Nfpa 1126 PDFДокумент24 страницыNfpa 1126 PDFL LОценок пока нет

- Existentialism in LiteratureДокумент2 страницыExistentialism in LiteratureGirlhappy Romy100% (1)

- 1 PBДокумент7 страниц1 PBIndah Purnama TaraОценок пока нет

- WBCS 2023 Preli - Booklet CДокумент8 страницWBCS 2023 Preli - Booklet CSurajit DasОценок пока нет

- Stucor Qp-Ec8095Документ16 страницStucor Qp-Ec8095JohnsondassОценок пока нет

- MCQ Floyd ElexДокумент87 страницMCQ Floyd ElexnicoleОценок пока нет

- Flow of FoodДокумент2 страницыFlow of FoodGenevaОценок пока нет

- Daily Lesson Log Quarter 1 Week 1Документ5 страницDaily Lesson Log Quarter 1 Week 1John Patrick Famadulan100% (1)

- Changed Report 2015 PDFДокумент298 страницChanged Report 2015 PDFAnonymous FKjeRG6AFnОценок пока нет