Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

2014 NUCJ 22 RvQrunngnut

Загружено:

NunatsiaqNews0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

3K просмотров14 страницJustice Earl Johnson, Nunavut Court of Justice

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документJustice Earl Johnson, Nunavut Court of Justice

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

3K просмотров14 страниц2014 NUCJ 22 RvQrunngnut

Загружено:

NunatsiaqNewsJustice Earl Johnson, Nunavut Court of Justice

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 14

nunavuumi iqkaqtuijikkut

NUNAVUT COURT OF JUSTICE

La Cour de justice du Nunavut

Citation: R v QRUNNGNUT, 2014 NUCJ 22

Date of Judgment: 20140813

File Number: 08-11-115

Registry: Iqaluit

Prosecutor: Her Majesty The Queen

-and-

Accused: Stephen Qrunngnut

________________________________________________________________________

Before The Honourable Mr. Justice E. Johnson

Counsel (Applicant): M. Girard

Counsel (Respondent): M. Christie

Location Heard: Iqaluit, Nunavut

Date Heard: January 30-31, 2013

Matters: Controlled Drugs and Substances Act S.C. 1996, c.

19 s. 5(4)

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

(NOTE: This document may have been edited for publication)

I. INTRODUCTION

[1] The accused is charged with unlawfully possessing less than 3

kilograms of cannabis marijuana for the purpose of trafficking

contrary to section 5(4) of the Controlled Drugs and Substances

Act S.C. 1996, c. 19. (CDSA).

[2] In a voir dire ruling found at 2013 NUCJ 08 [voir dire judgment], I

found the evidence seized by the police was admissible at trial

despite breaches of the accuseds Charter rights.

[3] Both Crown and Defence agreed that the evidence called at the

voir dire was admissible at the trial. The voir dire evidence

establishes that the accused checked two bags at the Ottawa

airport. One was his bag and the other was a bag he received

from a person known as Shawn (Shawns suitcase). When the

RCMP searched the two bags at the Iqaluit airport they found a

large panda bear in Shawns suitcase. Sewn into the panda bear

were 1649 grams of marijuana in five separate vacuum packed

bags that had a street value of $100,000.

[4] The Crown did not call any additional evidence at the trial and

the accused testified.

[5] I set a timeline for the filing of written submissions and reserved

judgment to August 13, 2014.

[6] Defence counsels written argument raised an issue on whether

the Crown had proved that the substance seized was cannabis

marijuana and I gave the Crown until July 11, 2014 to respond.

Attached to the written submissions of the Crown was a

certificate of analysis dated April 19, 2011 confirming that the

substance seized was cannabis marijuana (Certificate).

II. Issues

[7] Did the Crown prove that the substance seized was cannabis

marijuana?

[8] Was the accused in possession of cannabis marijuana?

Did the Crown prove that the substance seized was cannabis

marijuana?

A. Defence Argument

[9] Defence counsel argues that the Crown provided no evidence as

to the nature of the substance seized and the substance was not

admitted at trial. He argues the accused would have no way of

knowing what the substance was as he was never in possession

of it and only glimpsed it briefly.

B. Crown Argument

[10] The Crown provided a transcript of the June 14, 2013 court

appearance when the voir dire judgment was released and the

matter was adjourned to set a trial date. That transcript indicates

that Defence counsel admitted that there was no issue about the

nature of the substance and as a result the Crown did not tender

the Certificate.

C. Analysis

[11] Lines 22-24 of the Transcript reveal that Defence counsel agreed

there was no issue about the nature of the substance. It states:

Mr. Lane. Is there any dispute over the nature of the

substance?

Mr. Christie. No, substance no.

[12] I am satisfied that the Crown relied on this statement by Defence

counsel in deciding not to enter the Certificate as an exhibit in

the trial.

[13] I am satisfied that this statement by Defence counsel was an

admission under section 655 of the Criminal Code. It states:

655. Where an accused is on trial for an indictable offence, he or his

counsel may admit any fact alleged against him for the purpose of

dispensing with proof thereof.

[14] I am satisfied that the Crown would have tendered the Certificate

if Defence counsel had not made the admission.

[15] In the future counsel should use formal admissions under section

655 to avoid any misunderstandings.

Was the accused in possession of cannabis marijuana?

A. Crown Argument

[16] As held in R v Clouden 2011 ABQB 285, the Crown

acknowledges that it must prove three things to establish the

accused had possession of the 1649 grams of marijuana. First,

the Crown must prove that the accused had actual possession of

the marijuana. Second, that the accused knew he had actual

possession of the marijuana. Finally, that the accused exerted

control over the marijuana.

[17] The Crown argues that the accuseds evidence establishes that

he was in physical possession of Shawns suitcase and exerted

control over it until he gave it to his brother-in-law Silas

Kadlutsiak in Igloolik. From this fact and other evidence, the

court can infer that the accused actually knew he was

transporting the marijuana or that he was wilfully blind to that

possibility.

[18] As held in R v Jorgensen [1995] 4 SCR 55 [Jorgensen] wilful

blindness is not determined by applying an objective test but

rather by deciding whether the accused shut his eyes because

he knew or strongly suspected that looking would fix him with

knowledge.

[19] The Crown relies on the following facts to establish that the

accused was wilfully blind.

(a) He made no attempt to check with Silas to see if he was

expecting a suitcase from Shawn.

(b) The accuseds explanation to justify bringing a suitcase to

Igloolik to help people from Igloolik staying at Larga Baffin is

suspect because Shawn was not an Inuk, did not reside in

Nunavut and was not staying at Larga Baffin for medical

treatment. He was also a person that the accused had only met

once briefly in Igloolik.

(c) The explanation is further suspect because the accused knew

that Silas had supplied him with marijuana regularly over a four-

year period and that he was trafficking in marijuana.

Furthermore, the accused testified that when Shawn met him at

the airport he did not tell him the name of the person to whom

the suitcase was to be delivered.

(d) As the court has already held, the accused was not an

unsophisticated person and he gave conflicting versions about

the number of meetings he had with Shawn that undermine his

credibility. There is no commonality between Shawn and the

average patient residing at Larga Baffin and the accused was

aware of it.

[20] The inconsistencies in the accuseds evidence raise the very real

possibility that he was not being truthful and had actual

knowledge of the content of the suitcase. Cst. Allen testified that

that the one key he was given opened the padlocks on both

suitcases while the accused testified that he intended Shawns

suitcase to be checked under his daughters name. Furthermore,

Shawn asked the accused not to use the key to open the

suitcases. This evidence cannot be explained rationally or

culturally if the accused was not aware of the presence of drugs

in the suitcase.

[21] The accuseds explanation that he thought he was bringing up

Christmas presents and candies for Silas children is not

credible. Firstly, the accused never testified that the proximity to

Christmas made Shawns story more believable to him even

though it makes a perfect cover story for the delivery of drugs.

Secondly, the accused attempted to check Shawns suitcase

under his daughters name and he was told to bring the suitcase

to Silas immediately upon his arrival in Igloolik. If the request to

bring the suitcase was a legitimate favour to a Larga Baffin

resident that commonly occurred there would have been no

urgency to deliver it immediately. The accused did not mention

the proximity to Christmas because he knew the actual content

of the suitcase.

[22] The Crown does not have to prove actual knowledge and can

establish mens rea through wilful possession. There is a

significant amount of evidence that the accused made a

concerted effort not to become aware of the practicalities around

Shawns drug use. He testified that he did not ask Shawn if there

were drugs in Shawns suitcase because he did not expect him

to tell the truth. This evidence proves that the accuseds mind

was addressed to these possibilities. He should have been

suspicious when Shawn did not ask him until three days into his

stay at Larga Baffin to carry the suitcase. What is more telling is

that the accused attempted to have Shawns suitcase checked

under his daughters ticket and consented to the search thinking

that only his bag would be searched. He was not concerned

about a search of his bag because Cst. Allen had told him that

he would not be charged for a small amount of marijuana.

[23] If these facts do not lead to an inference that the accused

actually knew about the presence of drugs in his suitcase they

should convince this court that the four aspects described in

Sansregret v The Queen [1985] 1 SCR 570 [Sansregret] have

been satisfied. Those aspects are:

(a) Awareness of the need to make an inquiry;

(b) Declining to make the inquiry;

(c) Not wishing to know the truth;

(d) Preferring to remain ignorant.

[24] The accused became worried enough about Shawns suitcase

that he decided to check it under his daughters ticket. He also

did not ask Shawn about the contents of the suitcase or open it

with the key. These facts made him wilfully blind to the fact that

he was in possession of illicit drugs for the purpose of trafficking.

B. Defence Argument

[25] The Defence acknowledges that for the accused to be found in

possession of the marijuana, he would have to have knowledge

of the drugs. That knowledge could come from either actual

knowledge or wilful blindness about the drugs.

[26] The accused had no actual knowledge of the drugs. He testified

that he never opened the suitcase, had no idea what was in it

and only saw the marijuana at the airport after the search.

Furthermore, even if he opened up the suitcase he would not

have seen the drugs because they were sewn into the panda

bear.

[27] The accused relies on the statements about wilful blindness at

para 26 in R v Lagace [2003] OJ No 4328, 181 CCC (3d) 12

[Lagace] and at para 25 of R. v Bakos 2008 ONCA 712, [2008]

OJ No 4067 to argue that the test is subjective. Therefore this

court must be satisfied that the accused had a real or aroused

suspicion in his mind and then failed to make further inquiries.

[28] The following evidence from the accused that emerged after a

thorough cross-examination demonstrates that his suspicion was

not aroused.

(a) Shawn told the accused at the first meeting at the airport that

he wanted him to take toys and candies with him when he

travelled to Igloolik;

(b) Shawn told the accused that the toys and candies were going

to Silas who he had known for many years and who had three

young children;

(c) The accused believed that there were toys and candies in the

suitcase and that his belief was reasonable;

(d) The accused had no suspicion that there were drugs in the

suitcase;

(e) The accused did not think that it was strange for someone to

ask him to take a suitcase to give to Silas in Igloolik because he

has done it before and knew that many other people had done it

as well;

(f) The accused did not find it strange that someone would give

him money to carry the suitcase because others had paid him in

the past to do the same thing;

(g) The accused was not suspicious because he knew the family

to whom the suitcase was going;

(h) The accused was not interested in what was inside the

suitcase because Shawn had told him what was inside;

(i) The accused thought that people asked him to bring items to

the north because he was a nice guy.

[29] The accuseds pre-charge conduct supports his testimony that

he had no knowledge that there were drugs in the suitcase. As

Cst. Allen testified up to the point he was arrested, the accused

did not appear scared or afraid and remained polite. A person

with knowledge of the drugs or who was being wilfully blind

would have been nervous from the very first contact with the

RCMP. The accuseds demeanor was not consistent with

someone who knew or had a suspicion that they were

transporting 3.63 pounds of marijuana.

[30] It was only when the police brought in both suitcases that the

accused became worried. His worry at this point is reasonable

even though he never suspected the presence drugs in the

suitcase. He was in the presence of the RCMP who had been

found by this court in the voir dire judgment to have breached

some of his most important Charter rights and he viewed the

RCMP through Inuit eyes as being all-powerful and to be feared.

If the police said there were drugs in the suitcase it was

reasonable at that time for the accused to be worried.

[31] The accused was not much of a drug user and was not in a

position where he needed to be involved in drug trafficking to

obtain his drugs. He did not even smoke the six joints that

Shawn gave him despite having them in his possession for a few

days.

[32] The accuseds lack of a criminal record gives credence to his

claim of non-involvement.

[33] Defence counsel argues that the accused had no idea that there

were drugs in the suitcase and believed he was simply taking

toys and candy to children he knew in Igloolik as he and others

had done in the past.

[34] The accused repeated many times in his testimony that he was

not in the habit of prying into other peoples lives. The test for

wilful blindness is a subjective test and this evidence supports

his claim that he was not suspicious about the content of the

suitcase.

[35] Defence counsel submits that the accused was an innocent

helpful and descent person who was preyed upon because of

those attributes.

[36] In applying the test from R v W(D) [1991] 1 SCR 742 [R v W(D)],

Defence counsel submits that this court should find the

accuseds evidence was believable and trustworthy. The court

preferred his evidence on the Charter motion and he was

consistent even when pushed hard and repeatedly by Crown

counsel on the issue of wilful blindness. Alternatively, if this court

does not prefer the accuseds testimony to the Crown theory the

court should be left with a reasonable doubt and should acquit

the accused.

C. Analysis

[37] At para 22 of Sansregret, the Supreme Court of Canada

approved Glanville Williams definition of wilful blindness that

stated as follows:

The rule that wilful blindness is equivalent to knowledge is

essential, and is found throughout the criminal law. It is, at the

same time, an unstable rule, because judges are apt to forget its

very limited scope. A court can properly find wilful blindness

only where it can almost be said that the defendant actually

knew. He suspected the fact; he realized probability; but he

refrained from obtaining the final confirmation because he

wanted in the event to be able to deny knowledge. This, and this

alone, is wilful blindness. It requires in effect a finding that the

defendant intended to cheat the administration of justice. Any

wider definition would make the doctrine of wilful blindness

indistinguishable from the civil doctrine of negligence in not

obtaining knowledge.

[38] At para 103 of Jorgensen the Court refined the test and stated it

as follows:

A finding of wilful blindness involves an affirmative answer to the

question: Did the accused shut his eyes because he knew or strongly

suspected that looking would fix him with knowledge? Retailers who

suspect that the materials are obscene but refrain from making the

necessary inquiry in order to avoid being contaminated by knowledge

may be found to have been wilfully blind. The determination must be

made in light of all the circumstances. In Sansregret v. The Queen,

[1985] 1 S.C.R. 570, this Court held that the circumstances were not

restricted to those immediately surrounding the particular offense but

could be more broadly defined to encompass, for example, past events.

[39] In Lagace the Ontario Court of Appeal, at para 26, rejected the

Defence argument that wilful blindness required a level of

suspicion that amounted to a probability the vehicles were stolen

as follows:

I would reject this submission. I see no need to quantify the level of

suspicion beyond the recognition that it must be a real suspicion in the

mind of the accused that causes the accused to see the need for

inquiry: R. v. Sansregret (1985), 18 C.C.C. (3d) 223 at 235 (S.C.C.);

R. v. Jorgensen (1995), 102 C.C.C. (3d) 97 at 135 (S.C.C.); R. v.

Duong (1998), 124 C.C.C. (3d) 392 at 401-402 (Ont. C.A.).

[40] In Bakos the Ontario Court of Appeal, at para 25, approved the

trial judges charge on wilful blindness. He stated:

On this issue, the trial judge correctly charged the jury when he

described wilful blindness as comprising aroused suspicions on the

part of the appellants and deliberate omission to make further

inquiries.

[41] The Crown argues that the accused had actual knowledge that

the drugs were in his possession. This argument is based on the

inconsistencies in the accuseds evidence that undermine his

credibility and because he was a smart man. Additional facts that

suggest knowledge are the implausibility of the toys and candies

story, the fact that the accused did not ask Shawn what was in

the suitcase and that the accused attempted to check the

suitcase under his daughters name.

[42] I am satisfied that I cannot infer that the accused actually knew

there were illegal drugs in Shawns suitcase. I did not find that

the accused was a sophisticated man. In fact, at para 72 of the

voir dire judgment I stated that the accused was

unsophisticated although I also found that he had more

knowledge of English than suggested by Defence counsel.

[43] The Crown attacks the credibility of the accused because of his

divergent versions of his meeting with Shawn. I am satisfied that

the accuseds evidence was not inconsistent. He simply provided

more evidence at the trial than at the voir dire because he was

cross-examined more thoroughly.

[44] The story about the toys and candies is more plausible given the

proximity to Christmas even if the accused never mentioned it.

[45] The evidence obtained from the accused in the voir dire about

his intentions when he checked the two suitcases in Ottawa does

raise some suspicions that he knew Shawns suitcase might

contain drugs. He was thoroughly cross-examined by Mr. Lane at

the voir dire about it. The accused explained that he intended to

check his suitcase on his boarding pass and Shawns suitcase

on his daughters boarding pass. He did that because he was

concerned about the weight of the bags. He put his bag under

his name because his bag had a tag with his name on it. When

the accused consented to the search he thought the police would

only bring his bag and got worried when they brought both bags.

The accused denied he knew there were drugs in the bag he

received from Shawn when confronted by Mr. Lane. That is when

he became worried because the police had told him that they

thought there were drugs in the bag. He then thought they might

find something. The accused then confirmed again that he

thought the bag contained toys and candies and did not know

there were drugs in the bag.

[46] If the accused had opened the suitcase he received from Shawn

he would not have seen the drugs unless he did a thorough

search as was carried out by the police. On balance I am

satisfied that I cannot make the inference that the accused knew

there were drugs in the bag. However, I do find that this case

falls into the category described by Williams that it can almost

be said that the defendant actually knew (Sansregret at para

22).

[47] The final issue is whether the accused was wilfully blind to the

possible presence of drugs in the suitcase and then failed to

make further inquiries. The accused does not deny that he was

physically in possession of the suitcase and exerted control over

it. As held in Sansregret, I must now determine whether the

accused shut his eyes because he knew or strongly suspected

that looking would fix him with knowledge?

[48] Both Crown and Defence agree that the test to be applied to

answer this question is a subjective test. I must look at the

knowledge the accused possessed and assess if his suspicions

were aroused enough that he should have made further

inquiries.

[49] The Crown accurately points out that there are a number of

surrounding facts that objectively indicate the accused should

have been suspicious and have made further inquiries. He used

marijuana and received marijuana regularly from Silas including

around the time of the offence but never paid him for it. He had

only met Shawn once in the previous ten years when he showed

up at the airport on his arrival in Ottawa and he told him he had

some candies and toys for him to take to Igloolik. Shawn then

showed up unexpectedly at the hotel where the accused was

staying and gave him the suitcase to take to Igloolik. When he

gave the key to the suitcase he told him not open it up and to

deliver it to Silas immediately after he arrived in Igloolik. Shawn

gave the accused 5 marijuana cigarettes and $200 to deliver the

suitcase.

[50] The Crown relies on the evidence obtained from the accused

that he intended to have Shawns suitcase checked under his

daughters ticket to prove that he suspected there were drugs in

the suitcase. The Crown also points to the accuseds evidence

that he did not ask Shawn if there were drugs in the suitcase

because he did not think he would tell him the truth.

[51] The accuseds first argument is that the evidence summarized at

para 28 above should be believed. If I believe his evidence, I

should be satisfied that his suspicions were not aroused and he

had no basis to make further inquiries.

[52] I am satisfied that the accused suspected that there might be

drugs in Shawns suitcase because his explanation for

attempting to check Shawns suitcase on his daughters ticket

does not make any sense. His initial response was that he was

concerned about the weight of his suitcase but he never weighed

them and had no knowledge of the weight limitation. When the

Crown probed further he then explained that he checked his bag

on his ticket because it had a tag with his name on it.

[53] The accuseds belief that Shawns suitcase was checked under

his daughters ticket would also explain why he did not appear

nervous to the police. He was sure that the police would bring his

bag for a search and when he saw both bags he knew there was

a reason to worry.

[54] Further the accused admitted that he thought about asking

Shawn if there were drugs in the suitcase but did not because he

thought he would lie. The fact that the accused thought that he

would not get a straight answer from Shawn proves his

suspicions were aroused.

[55] I therefore reject the evidence of the accused that he was not

suspicious about the presence of drugs in Shawns suitcase.

[56] Since I do not accept the evidence of the accused I must ask

myself if I am left in reasonable doubt by it. I am satisfied that his

evidence does not leave me with a reasonable doubt.

[57] The final part of the R v W(D) test is to consider whether the rest

of the evidence of the accused that I do accept satisfies me

beyond a reasonable doubt of his guilt. I am satisfied that I am

not left with a reasonable doubt.

[58] I find the accused was wilfully blind to the presence of drugs in

Shawns suitcase and did not make further inquiries because he

knew he would find out that there were drugs in the suitcase. To

once again use the words of Williams he realized probability; but

he refrained from obtaining the final confirmation because he

wanted in the event to be able to deny knowledge.

[59] I therefore convict the accused of possession of cannabis

marijuana for the purpose of trafficking contrary to section 5(4) of

the CDSA.

Dated at the City of Iqaluit this 13th day of August, 2014

_______________________

Mr. Justice Earl D. Johnson

Nunavut Court of Justice

Вам также может понравиться

- Application For Authorization of A Class ActionДокумент18 страницApplication For Authorization of A Class ActionNunatsiaqNewsОценок пока нет

- 2021 Nuca 11Документ9 страниц2021 Nuca 11NunatsiaqNewsОценок пока нет

- Nunavik Housing Needs Survey 2021Документ44 страницыNunavik Housing Needs Survey 2021NunatsiaqNewsОценок пока нет

- Jane Doe V Pangnirtung, Nunavut, 2020 NUCJ 48Документ6 страницJane Doe V Pangnirtung, Nunavut, 2020 NUCJ 48NunatsiaqNewsОценок пока нет

- Qaqqaq Housingreport 2021Документ22 страницыQaqqaq Housingreport 2021NunatsiaqNews0% (1)

- Application For Authorization - Nunavik Victims of CrimeДокумент18 страницApplication For Authorization - Nunavik Victims of CrimeNunatsiaqNewsОценок пока нет

- R Vs EvalikДокумент17 страницR Vs EvalikNunatsiaqNewsОценок пока нет

- R. V Choquette, 2021 NUCJ 10Документ13 страницR. V Choquette, 2021 NUCJ 10NunatsiaqNewsОценок пока нет

- Public Guardian and Eaton V Eaton, 2021 NUCJ 21Документ6 страницPublic Guardian and Eaton V Eaton, 2021 NUCJ 21NunatsiaqNewsОценок пока нет

- Cour de Justice Du NunavutДокумент12 страницCour de Justice Du NunavutNunatsiaqNewsОценок пока нет

- R. V Pauloosie, 2021 NUCJ 9Документ6 страницR. V Pauloosie, 2021 NUCJ 9NunatsiaqNewsОценок пока нет

- Cour de Justice Du NunavutДокумент12 страницCour de Justice Du NunavutNunatsiaqNewsОценок пока нет

- TD 360 5 (2) en Staff Housing Distribution ReportДокумент19 страницTD 360 5 (2) en Staff Housing Distribution ReportNunatsiaqNewsОценок пока нет

- GN RFP For Inuit and Indigenous Support Addictions Treatment ProgramsДокумент52 страницыGN RFP For Inuit and Indigenous Support Addictions Treatment ProgramsNunatsiaqNewsОценок пока нет

- R. V Qirqqut, 2021 NUCJ 4Документ10 страницR. V Qirqqut, 2021 NUCJ 4NunatsiaqNewsОценок пока нет

- 211FactSheet National NunavutДокумент2 страницы211FactSheet National NunavutNunatsiaqNewsОценок пока нет

- Mary River Financial SubmissionДокумент10 страницMary River Financial SubmissionNunatsiaqNewsОценок пока нет

- R V Akpik, 2021Документ13 страницR V Akpik, 2021NunatsiaqNewsОценок пока нет

- Financial Analysis: Mary River Iron Ore MineДокумент23 страницыFinancial Analysis: Mary River Iron Ore MineNunatsiaqNewsОценок пока нет

- R V Ford, 2021 Nucj 7Документ27 страницR V Ford, 2021 Nucj 7NunatsiaqNewsОценок пока нет

- R V Audlakiak, 2020 NUCJ 41Документ8 страницR V Audlakiak, 2020 NUCJ 41NunatsiaqNewsОценок пока нет

- 210212-08MN053-NIRB LTR Parties Re Draft Extended PH Agenda-OEDEДокумент19 страниц210212-08MN053-NIRB LTR Parties Re Draft Extended PH Agenda-OEDENunatsiaqNewsОценок пока нет

- R V Aklok, 2020 NUCJ 37Документ26 страницR V Aklok, 2020 NUCJ 37NunatsiaqNewsОценок пока нет

- R V Cooper-Flaherty, 2020 NUCJ 43Документ10 страницR V Cooper-Flaherty, 2020 NUCJ 43NunatsiaqNewsОценок пока нет

- R V Josephee, 2020 NUCJ 40Документ8 страницR V Josephee, 2020 NUCJ 40NunatsiaqNewsОценок пока нет

- Jagmeet Singh Letter To Prime Minister Trudeau Support For Nunavut During COVID 19 Outbreak 20201125 enДокумент2 страницыJagmeet Singh Letter To Prime Minister Trudeau Support For Nunavut During COVID 19 Outbreak 20201125 enNunatsiaqNewsОценок пока нет

- R. v. Ameralik, 2021 NUCJ 3Документ21 страницаR. v. Ameralik, 2021 NUCJ 3NunatsiaqNewsОценок пока нет

- Pond Inlet Announcement On Phase 2 DevelopmentДокумент4 страницыPond Inlet Announcement On Phase 2 DevelopmentNunatsiaqNewsОценок пока нет

- R V Tower Arctic, 2020 NUCJ 39Документ9 страницR V Tower Arctic, 2020 NUCJ 39NunatsiaqNewsОценок пока нет

- NIRB Pre-Hearing Decision Report Mary River Phase 2Документ117 страницNIRB Pre-Hearing Decision Report Mary River Phase 2NunatsiaqNewsОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Kawamura V Boyd Gaming CorpДокумент52 страницыKawamura V Boyd Gaming CorpAndrew GallardoОценок пока нет

- Crimp RoooДокумент12 страницCrimp RoooDiane UyОценок пока нет

- Criminal Law Homicide Problem QuestionДокумент7 страницCriminal Law Homicide Problem Questionjaydizzlegear100% (2)

- Practice Direction 14.3 Appendix AДокумент2 страницыPractice Direction 14.3 Appendix AFrannis AnnyОценок пока нет

- PIT 2 - 916 Nowy Wzór 2023 PDF ENGДокумент3 страницыPIT 2 - 916 Nowy Wzór 2023 PDF ENGСофія РудикОценок пока нет

- Fecr013118 PDFДокумент46 страницFecr013118 PDFthesacnewsОценок пока нет

- Trade and Investment V CSCДокумент2 страницыTrade and Investment V CSCSocОценок пока нет

- Sro 42Документ8 страницSro 42zainallliОценок пока нет

- Labiano Succession DigestДокумент2 страницыLabiano Succession DigestKrishianne LabianoОценок пока нет

- Article 141 - Conspiracy To Commit SeditionДокумент8 страницArticle 141 - Conspiracy To Commit SeditionJd FadОценок пока нет

- In The Court of The City Civil Judge at Bangalore (Cch-3)Документ7 страницIn The Court of The City Civil Judge at Bangalore (Cch-3)Erika HarrisОценок пока нет

- People of The Philippines vs. Eduardo SampiorДокумент6 страницPeople of The Philippines vs. Eduardo SampiorPeterD'Rock WithJason D'ArgonautОценок пока нет

- THE - QUEEN - v. - PRICE. - (1884) - 12 - Q.B.D. - 247.PDF ( (Inquest) )Документ7 страницTHE - QUEEN - v. - PRICE. - (1884) - 12 - Q.B.D. - 247.PDF ( (Inquest) )zac mankirОценок пока нет

- Motion Set Aside Default GA Magistrate CourtДокумент9 страницMotion Set Aside Default GA Magistrate CourtJanet and James80% (5)

- Role of Courts in Granting Bails and Bail Reforms: TH THДокумент1 страницаRole of Courts in Granting Bails and Bail Reforms: TH THSamarth VikramОценок пока нет

- For Maintenance of Peaceful Possession: David V Rivera FACTS: Claiming To Be The Owner of An Eighteen ThousandДокумент8 страницFor Maintenance of Peaceful Possession: David V Rivera FACTS: Claiming To Be The Owner of An Eighteen ThousanddoraemoanОценок пока нет

- Ombudsman vs. Estandarte, 521 SCRA 155Документ13 страницOmbudsman vs. Estandarte, 521 SCRA 155almorsОценок пока нет

- Indiana University Responds To Lawsuit From Professor Phil McPhailДокумент41 страницаIndiana University Responds To Lawsuit From Professor Phil McPhailThe College FixОценок пока нет

- Contempt CourtДокумент2 страницыContempt CourtSankalp YadavОценок пока нет

- Applicability of The Payment of Gratuity ACT, 1972 in Private Educational InstitutionsДокумент4 страницыApplicability of The Payment of Gratuity ACT, 1972 in Private Educational Institutionsadventure of Jay KhatriОценок пока нет

- The Rule of Common LawДокумент108 страницThe Rule of Common LawNishal KiniОценок пока нет

- People V PinedaДокумент3 страницыPeople V PinedajennyMBОценок пока нет

- Professional Ethics CaseДокумент15 страницProfessional Ethics CaseVivek GautamОценок пока нет

- Cadastral ProceedingsДокумент1 страницаCadastral ProceedingsRaffyLaguesmaОценок пока нет

- Secondary (English) Masbate 9-2019 PDFДокумент23 страницыSecondary (English) Masbate 9-2019 PDFPhilBoardResultsОценок пока нет

- Bliss Development Corporation vs. NLRCДокумент12 страницBliss Development Corporation vs. NLRCRose Anne MenorОценок пока нет

- Art 14 Par 17 - People Vs BumidangДокумент9 страницArt 14 Par 17 - People Vs BumidangAyban NabatarОценок пока нет

- Law of Evidence Lecture Notes.Документ8 страницLaw of Evidence Lecture Notes.ISAAC ADUSI-POKUОценок пока нет

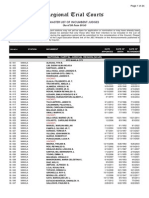

- RTC Incumbent JudgesДокумент24 страницыRTC Incumbent JudgesRaymond RamseyОценок пока нет

- Joseph M. Kalady v. Joe W. Booker, Warden and United States Parole Commission, 104 F.3d 367, 10th Cir. (1996)Документ5 страницJoseph M. Kalady v. Joe W. Booker, Warden and United States Parole Commission, 104 F.3d 367, 10th Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет