Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

06 Succession With Charts

Загружено:

Matt MedinaАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

06 Succession With Charts

Загружено:

Matt MedinaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

06 Week. Succession. ALS 3C. 2013. Justice Hofilena.

1

CONTENTS

FOR RECIT AFTER MIDTERMS ................................................................................................................ 1

25. Arts. 955 1002 (See Tolentino comment on Art. 999).................................................. 1

1. Pascual v Pascual Bautista 207 SCRA 561 MOMMY ..................................................... 5

2. Landayan v Bacani 117 SCRA 117 GASTON .................................................................... 6

3. Manuel v Ferrer 247 SCRA 476 CARLO SANCHEZ ........................................................ 8

4. Rosales v Rosales 128 SCRA 69 NORBY ............................................................................ 8

5. Berciles v GSIS 138 SCRA 53 MAITI ................................................................................. 10

26. Arts. 1003 1014 .......................................................................................................................... 11

1. City of Manila v Archbishop of Manila 36 Phil 815 LEX AQUINO .......................... 12

2. Adlawan v Adlawan 479 SCRA 275 (jan 2006) DONDON ......................................... 13

27. Arts. 1015 1023 MEMORIZE Art. 1015 ............................................................................ 14

1. Torres v Lopez 49 Phil 504 PENDIX ................................................................................. 15

28. Arts. 1024 1028 .......................................................................................................................... 16

29. Arts. 1029 1040 .......................................................................................................................... 17

1. Nepomuceno v CA 139 SCRA 217 HADDY ..................................................................... 18

2. Villavicencio v Qinio GR 45248 April 18, 1939 KEITH .............................................. 20

3. Cayetano v Leonidas 129 SCRA 522 RIO ........................................................................ 21

30. Arts. 1041 1048 .......................................................................................................................... 23

31. Arts. 1049 1057 .......................................................................................................................... 24

1. Avelino v CA 329 SCRA 368 JECH ...................................................................................... 25

32. Arts. 1058 1077 .......................................................................................................................... 26

1. Zaragoza v CA 341 SCRA 309 DEBBIE LIM .................................................................... 27

2. Adan v Casili 76 Phil 279 JELI............................................................................................. 29

3. Dizon Rivera v Dizon 9 SCRA 555 REGGIE ..................................................................... 30

33. Arts. 1078 1090 .......................................................................................................................... 32

1. Garcia v Calaliman 172 SCRA 201 BELLE....................................................................... 33

2. Balanay Jr v Martinez 64 SCRA 454 MUTI...................................................................... 34

3. Alejandrino v CA 295 SCRA 538 JAMON ........................................................................ 36

4. Cua v Vargas 506 SCRA 374 ANGEL ................................................................................. 37

5. J.L.T. Agro Inc. v Balansag 453 SCRA 211 TRISTAN ................................................... 39

6. Chavez v IAC 191 SCRA 211 MARIANA .......................................................................... 42

7. Santiago v Santiago v 627 SCRA 351 ELLIE .................................................................. 43

8. Barcelona v Barcelona 58 Official Gazette 373 JAPS case not found ................. 45

9. Bautista v Grino-Aquino 168 SCRA 790 MEME ........................................................... 45

34. Arts. 1091 1105 .......................................................................................................................... 47

1. Bautista v Bautista 529 SCRA 187 CJ NARVASA .......................................................... 51

2. Reyes v RTC of Makati Br. 142 561 SCRA 593 JP ORTIZ........................................... 52

FOR RECIT AFTER MIDTERMS

25. ARTS. 955 1002 (SEE TOLENTINO COMMENT ON ART. 999)

Art. 955. The legatee or devisee of two legacies or devises, one of which is onerous,

cannot renounce the onerous one and accept the other. If both are onerous or

gratuitous, he shall be free to accept or renounce both, or to renounce either. But if the

testator intended that the two legacies or devises should be inseparable from each

other, the legatee or devisee must either accept or renounce both.

Any compulsory heir who is at the same time a legatee or devisee may waive the

inheritance and accept the legacy or devise, or renounce the latter and accept the

former, or waive or accept both. (890a)

Art. 956. If the legatee or devisee cannot or is unwilling to accept the legacy or devise, or

if the legacy or devise for any reason should become ineffective, it shall be merged into

the mass of the estate, except in cases of substitution and of the right of accretion.

(888a)

Art. 957. The legacy or devise shall be without effect:

(1) If the testator transforms the thing bequeathed in such a manner that it

does not retain either the form or the denomination it had;

06 Week. Succession. ALS 3C. 2013. Justice Hofilena.

2

(2) If the testator by any title or for any cause alienates the thing bequeathed

or any part thereof, it being understood that in the latter case the legacy or

devise shall be without effect only with respect to the part thus alienated. If

after the alienation the thing should again belong to the testator, even if it be

by reason of nullity of the contract, the legacy or devise shall not thereafter be

valid, unless the reacquisition shall have been effected by virtue of the exercise

of the right of repurchase;

(3) If the thing bequeathed is totally lost during the lifetime of the testator, or

after his death without the heir's fault. Nevertheless, the person obliged to pay

the legacy or devise shall be liable for eviction if the thing bequeathed should

not have been determinate as to its kind, in accordance with the provisions of

Article 928. (869a)

Art. 958. A mistake as to the name of the thing bequeathed or devised, is of no

consequence, if it is possible to identify the thing which the testator intended to

bequeath or devise. (n)

Art. 959. A disposition made in general terms in favor of the testator's relatives shall be

understood to be in favor of those nearest in degree. (751)

CHAPTER 3

LEGAL OR INTESTATE SUCCESSION

SECTION 1. - General Provisions

Art. 960. Legal or intestate succession takes place:

(1) If a person dies without a will, or with a void will, or one which has

subsequently lost its validity;

(2) When the will does not institute an heir to, or dispose of all the property

belonging to the testator. In such case, legal succession shall take place only

with respect to the property of which the testator has not disposed;

(3) If the suspensive condition attached to the institution of heir does not

happen or is not fulfilled, or if the heir dies before the testator, or repudiates

the inheritance, there being no substitution, and no right of accretion takes

place;

(4) When the heir instituted is incapable of succeeding, except in cases

provided in this Code. (912a)

Art. 961. In default of testamentary heirs, the law vests the inheritance, in accordance

with the rules hereinafter set forth, in the legitimate and illegitimate relatives of the

deceased, in the surviving spouse, and in the State. (913a)

Art. 962. In every inheritance, the relative nearest in degree excludes the more distant

ones, saving the right of representation when it properly takes place.

Relatives in the same degree shall inherit in equal shares, subject to the provisions of

article 1006 with respect to relatives of the full and half blood, and of Article 987,

paragraph 2, concerning division between the paternal and maternal lines. (912a)

SUBSECTION 1. - Relationship

Art. 963. Proximity of relationship is determined by the number of generations. Each

generation forms a degree. (915)

Art. 964. A series of degrees forms a line, which may be either direct or collateral.

A direct line is that constituted by the series of degrees among ascendants and

descendants.

A collateral line is that constituted by the series of degrees among persons who are not

ascendants and descendants, but who come from a common ancestor. (916a)

Art. 965. The direct line is either descending or ascending.

The former unites the head of the family with those who descend from him.

The latter binds a person with those from whom he descends. (917)

Art. 966. In the line, as many degrees are counted as there are generations or persons,

excluding the progenitor.

In the direct line, ascent is made to the common ancestor. Thus, the child is one degree

removed from the parent, two from the grandfather, and three from the great-

grandparent.

In the collateral line, ascent is made to the common ancestor and then descent is made

to the person with whom the computation is to be made. Thus, a person is two degrees

removed from his brother, three from his uncle, who is the brother of his father, four

from his first cousin, and so forth. (918a)

06 Week. Succession. ALS 3C. 2013. Justice Hofilena.

3

Art. 967. Full blood relationship is that existing between persons who have the same

father and the same mother.

Half blood relationship is that existing between persons who have the same father, but

not the same mother, or the same mother, but not the same father. (920a)

Art. 968. If there are several relatives of the same degree, and one or some of them are

unwilling or incapacitated to succeed, his portion shall accrue to the others of the same

degree, save the right of representation when it should take place. (922)

Art. 969. If the inheritance should be repudiated by the nearest relative, should there be

one only, or by all the nearest relatives called by law to succeed, should there be several,

those of the following degree shall inherit in their own right and cannot represent the

person or persons repudiating the inheritance. (923)

SUBSECTION 2. - Right of Representation

Art. 970. Representation is a right created by fiction of law, by virtue of which the

representative is raised to the place and the degree of the person represented, and

acquires the rights which the latter would have if he were living or if he could have

inherited. (942a)

Art. 971. The representative is called to the succession by the law and not by the person

represented. The representative does not succeed the person represented but the one

whom the person represented would have succeeded. (n)

Art. 972. The right of representation takes place in the direct descending line, but never

in the ascending.

In the collateral line, it takes place only in favor of the children of brothers or sisters,

whether they be of the full or half blood. (925)

Art. 973. In order that representation may take place, it is necessary that the

representative himself be capable of succeeding the decedent. (n)

Art. 974. Whenever there is succession by representation, the division of the estate shall

be made per stirpes, in such manner that the representative or representatives shall not

inherit more than what the person they represent would inherit, if he were living or

could inherit. (926a)

Art. 975. When children of one or more brothers or sisters of the deceased survive, they

shall inherit from the latter by representation, if they survive with their uncles or aunts.

But if they alone survive, they shall inherit in equal portions. (927)

Art. 976. A person may represent him whose inheritance he has renounced. (928a)

Art. 977. Heirs who repudiate their share may not be represented. (929a)

SECTION 2. - Order of Intestate Succession

SUBSECTION 1. - Descending Direct Line

Art. 978. Succession pertains, in the first place, to the descending direct line. (930)

Art. 979. Legitimate children and their descendants succeed the parents and other

ascendants, without distinction as to sex or age, and even if they should come from

different marriages.

An adopted child succeeds to the property of the adopting parents in the same manner

as a legitimate child. (931a)

Art. 980. The children of the deceased shall always inherit from him in their own right,

dividing the inheritance in equal shares. (932)

Art. 981. Should children of the deceased and descendants of other children who are

dead, survive, the former shall inherit in their own right, and the latter by right of

representation. (934a)

Art. 982. The grandchildren and other descendants shall inherit by right of

representation, and if any one of them should have died, leaving several heirs, the

portion pertaining to him shall be divided among the latter in equal portions. (933)

Art. 983. If illegitimate children survive with legitimate children, the shares of the

former shall be in the proportions prescribed by Article 895. (n)

Art. 984. In case of the death of an adopted child, leaving no children or descendants, his

parents and relatives by consanguinity and not by adoption, shall be his legal heirs. (n)

SUBSECTION 2. - Ascending Direct Line

06 Week. Succession. ALS 3C. 2013. Justice Hofilena.

4

Art. 985. In default of legitimate children and descendants of the deceased, his parents

and ascendants shall inherit from him, to the exclusion of collateral relatives. (935a)

Art. 986. The father and mother, if living, shall inherit in equal shares.

Should one only of them survive, he or she shall succeed to the entire estate of the child.

(936)

Art. 987. In default of the father and mother, the ascendants nearest in degree shall

inherit.

Should there be more than one of equal degree belonging to the same line they shall

divide the inheritance per capita; should they be of different lines but of equal degree,

one-half shall go to the paternal and the other half to the maternal ascendants. In each

line the division shall be made per capita. (937)

SUBSECTION 3. - Illegitimate Children

Art. 988. In the absence of legitimate descendants or ascendants, the illegitimate

children shall succeed to the entire estate of the deceased. (939a)

Art. 989. If, together with illegitimate children, there should survive descendants of

another illegitimate child who is dead, the former shall succeed in their own right and

the latter by right of representation. (940a)

Art. 990. The hereditary rights granted by the two preceding articles to illegitimate

children shall be transmitted upon their death to their descendants, who shall inherit by

right of representation from their deceased grandparent. (941a)

Art. 991. If legitimate ascendants are left, the illegitimate children shall divide the

inheritance with them, taking one-half of the estate, whatever be the number of the

ascendants or of the illegitimate children. (942-841a)

Art. 992. An illegitimate child has no right to inherit ab intestato from the legitimate

children and relatives of his father or mother; nor shall such children or relatives inherit

in the same manner from the illegitimate child. (943a)

Art. 993. If an illegitimate child should die without issue, either legitimate or illegitimate,

his father or mother shall succeed to his entire estate; and if the child's filiation is duly

proved as to both parents, who are both living, they shall inherit from him share and

share alike. (944)

Art. 994. In default of the father or mother, an illegitimate child shall be succeeded by his

or her surviving spouse who shall be entitled to the entire estate.

If the widow or widower should survive with brothers and sisters, nephews and nieces,

she or he shall inherit one-half of the estate, and the latter the other half. (945a)

SUBSECTION 4. - Surviving Spouse

Art. 995. In the absence of legitimate descendants and ascendants, and illegitimate

children and their descendants, whether legitimate or illegitimate, the surviving spouse

shall inherit the entire estate, without prejudice to the rights of brothers and sisters,

nephews and nieces, should there be any, under article 1001. (946a)

Art. 996. If a widow or widower and legitimate children or descendants are left, the

surviving spouse has in the succession the same share as that of each of the children.

(834a)

Art. 997. When the widow or widower survives with legitimate parents or ascendants,

the surviving spouse shall be entitled to one-half of the estate, and the legitimate parents

or ascendants to the other half. (836a)

Art. 998. If a widow or widower survives with illegitimate children, such widow or

widower shall be entitled to one-half of the inheritance, and the illegitimate children or

their descendants, whether legitimate or illegitimate, to the other half. (n)

Art. 999. When the widow or widower survives with legitimate children or their

descendants and illegitimate children or their descendants, whether legitimate or

illegitimate, such widow or widower shall be entitled to the same share as that of a

legitimate child. (n)

Art. 1000. If legitimate ascendants, the surviving spouse, and illegitimate children are

left, the ascendants shall be entitled to one-half of the inheritance, and the other half

shall be divided between the surviving spouse and the illegitimate children so that such

widow or widower shall have one-fourth of the estate, and the illegitimate children the

other fourth. (841a)

Art. 1001. Should brothers and sisters or their children survive with the widow or

widower, the latter shall be entitled to one-half of the inheritance and the brothers and

sisters or their children to the other half. (953, 837a)

06 Week. Succession. ALS 3C. 2013. Justice Hofilena.

5

Art. 1002. In case of a legal separation, if the surviving spouse gave cause for the

separation, he or she shall not have any of the rights granted in the preceding articles.

(n)

1. PASCUAL V PASCUAL BAUTISTA 207 SCRA 561 MOMMY

EMERGENCY RECIT:

FACTS:

Petitioners Olivia and Hermes Pascual are the acknowledged natural children of the late

Eligio Pascual, the latter being a full blood brother of the decedent Don Andres Pascual,

who died intestate without any issue, legitimate, acknowledged natural, adopted or

spurious children.. Adela Soldevilla Pascual the surviving spouse of the late Don Andes

Pascual filed w/ the RTC Branch 162, a special proceeding case no.7554 for

administration of the intestate estate of her late husband. Olivia and Hermes are

illegitimate children of Eligio Pascual (although they contend that the term illegitimate

children as described in art 992 should be construed as spurious children).

ISSUE:

Whether or not Article 992 of the Civil Code of the Philippines, can be interpreted to

exclude recognized natural children from the inheritance of the deceased.

HELD:

Article 992 of the Civil Code provides a barrier or iron curtain in that it prohibits

absolutely a succession ab intestato between the illegitimate child and the legitimate

children and relatives of the father or mother of said legitimate child. They may have a

natural tie of blood, but this is not recognized by law for the purposes of Article 992.

Eligio Pascual is a legitimate child but petitioners are his illegitimate children.

Applying the above doctrine to the case at bar, respondent IAC did not err in holding

that petitioners herein cannot represent their father Eligio Pascual in the succession of

the latter to the intestate estate of the decedent Andres Pascual, full blood brother of

their father.

COMPLETE

FACTS

Olivia and Hermes Pascual are the acknowledged natural children of the late Eligio

Pascual, who is a full blood brother of the decedent Don Andres Pascual

Don Andres Pascual died intestate without any issue, legitimate, acknowledged natural,

adopted or spurious children and was survived by the following:

(a) Adela Soldevilla de Pascual, surviving spouse;

(b) Children of Wenceslao Pascual, Sr., a brother of the full blood of the

deceased

Esperanza C. Pascual-Bautista

Manuel C. Pascual

Jose C. Pascual

Susana C. Pascual-Bautista

Erlinda C. Pascual

Wenceslao C. Pascual, Jr.

(c) Children of Pedro-Bautista, brother of the half blood of the deceased

Avelino Pascual

Isoceles Pascual

Loida Pascual-Martinez

Virginia Pascual-Ner

Nona Pascual-Fernando

Octavio Pascual

Geranaia Pascual-Dubert;

(d) Acknowledged natural children of Eligio Pascual, brother of the full blood

of the deceased

Olivia S. Pascual

Hermes S. Pascual

(e) Intestate of Eleuterio T. Pascual, a brother of the half blood of the deceased

and represented by the following:

Dominga M. Pascual

Mamerta P. Fugoso

Abraham S. Sarmiento, III

Regina Sarmiento-Macaibay

Eleuterio P. Sarmiento

Domiga P. San Diego

Nelia P. Marquez

Dad m. Mom

Don Andres Pascual m.

Adela Soldevilla Pascual

Eligio Pascual

Olivia (Acknowledged

Natural Child)

Hermes (Acknowledged

Natural Child)

06 Week. Succession. ALS 3C. 2013. Justice Hofilena.

6

Silvestre M. Pascual

Eleuterio M. Pascual

Adela, the wife of the late Don Andres Pascual, filed with the RTC a special proceeding

for administration of the intestate estate of her late husband. Adela then filed a

Supplemental Petition to the Petition for letters of Administration, where she expressly

stated that Olivia Pascual and Hermes Pascual, are among the heirs of Don Andres

Pascual.

Again Adela executed a affidavit, to the effect that of her own knowledge, Eligio Pascual

is the younger full blood brother of her late husband Don Andres Pascual, to belie the

statement made by the oppositors, that they were are not among the known heirs of the

deceased Don Andres Pascual . All the above-mentioned heirs entered into a

COMPROMISE AGREEMENT, over the vehement objections of the Olivia and Hermes,

although paragraph V of such compromise agreement provides, to wit:

This Compromise Agreement shall be without prejudice to the

continuation of the above-entitled proceedings until the final

determination thereof by the court, or by another compromise

agreement, as regards the claims of Olivia Pascual and Hermes

Pascual as legal heirs of the deceased, Don Andres Pascual.

The Agreement had been entered into despite the Manifestation/Motion of the

petitioners Olivia and Hermes, manifesting their hereditary rights in the intestate estate

of Don Andres Pascual, their uncle.

Olivia and Hermes filed their Motion to Reiterate Hereditary Rights and the

Memorandum in Support of Motion to reiterate Hereditary Rights. The RTC denied the

motion reiterating the hereditary rights of Olivia and Hermes. CA affirmed RTC decision.

ISSUE

W/N Article 992 of the Civil Code can be interpreted to exclude recognized natural

children from the inheritance of the deceased.

HELD

Petition dismissed. CA decision Affirmed.

RATIO

Article 992 of the civil Code, provides:

An illegitimate child has no right to inherit ab intestato from the

legitimate children and relatives of his father or mother; nor shall

such children or relatives inherit in the same manner from the

illegitimate child.

The issue in this case had already been laid to rest in Diaz v. IAC, supra, where this Court

ruled that:

Article 992 of the Civil Code provides a barrier or iron curtain in that

it prohibits absolutely a succession ab intestato between the

illegitimate child and the legitimate children and relatives of the

father or mother of said legitimate child. They may have a natural tie

of blood, but this is not recognized by law for the purposes of Article

992. Between the legitimate family and illegitimate family there is

presumed to be an intervening antagonism and incompatibility. The

illegitimate child is disgracefully looked down upon by the legitimate

family; the family is in turn hated by the illegitimate child; the latter

considers the privileged condition of the former, and the resources of

which it is thereby deprived; the former, in turn, sees in the

illegitimate child nothing but the product of sin, palpable evidence of

a blemish broken in life; the law does no more than recognize this

truth, by avoiding further grounds of resentment.

Eligio Pascual is a legitimate child but petitioners are his illegitimate children.

IAC did not err in holding that Olivia and Hermes cannot represent their father Eligio

Pascual in the succession of the latter to the intestate estate of the decedent Andres

Pascual, full blood brother of their father.

2. LANDAYAN V BACANI 117 SCRA 117 GASTON

Landayan Version

1st m. 2nd m. 3rd m.

Florencia Bautista Antera Mandap

Maxima Andrada

(respondent)

I

Guillerma

Abenojar

I I

Severino Abenojar

(illegitimate)

Maria, Segundo,

Marcial, Lucio

(legitimate)

Teodoro

06 Week. Succession. ALS 3C. 2013. Justice Hofilena.

7

Andrada and Abenojar Version

Facts

1. Teodoro Abenojar (Teodoro) died intestate and left several properties (land, house

and improvements in Pangasinan and Manila)

2. Private respondents Maxima Andrada, Teodoros surviving spouse, and Severino

Abenojar partitioned the estate of Teodoro among themselves.

3. Petitioners (Landayan) filed a case with the CFI seeking a judicial declaration that

they are Teodoros legal heirs and to annul the extra-judicial partition (fact 2)

4. LANDAYAN contends, inter alia, that Severino Abenojar is an illegitimate child and

therefore that the partition is therefore void as to him.

5. Private respondents (Andrada and Severino) aver that the petitioners (Landayan)

right to bring an action to annul an extrajudicial on the basis of fraud has already

prescribed. Such right, according to them, expires in 4 years and here, 18 years

have already passed.

6. Lower courts rule in favor of the petitioners and dismiss the case.

Issue: W/N the action has prescribed.

Held: WHEREFORE, the Order appealed from is hereby REVERSED and SET ASIDE. The

respondent Judge is ordered to try the case on the merits and render the corresponding

judgment thereon. The private respondents shall pay the costs.

Ratio:

Petitioners contend that Severino Abenojar is not a legal heir of Teodoro Abenojar,

he being only an acknowledged natural child of Guillerma Abenojar, the mother of

petitioners, whom they claim to be the sole legitimate daughter in first marriage of

Teodoro Abenojar. If this claim is correct, Severino Abenojar has no rights of legal

succession from

Teodoro Abenojar in view of the express provision of Article 992 of the Civil Code,

which

reads as follows:

o ART. 992. An illegitimate child has no right to inherit ab intestato from the

legitimate children and relatives of his father or mother; nor shall such

children or relatives inherit in the same manner from the illegitimate

child.

The right of Severino Abenojar to be considered a legal heir of Teodoro Abenojar

depends

on the truth of his allegations that he is not an illegitimate child of Guillerma

Abenojar, but an

acknowledged natural child of Teodoro Abenojar. On this assumption, his right

to inherit from

Teodoro Abenojar is recognized by law (Art. 998, Civil Code).

Should the petitioners be able to substantiate their contention that Severino

Abenojar is an

illegitimate son of Guillerma Abenojar, he is not a legal heir of Teodoro

Abenojar. The right of

representation is denied by law to an illegitimate child who is disqualified to

inherit ab

intestato from the legitimate children and relatives of Ms father. (Art. 992, Civil

Code). On this

supposition, the subject deed of extra- judicial partition is one that included a

person who is

not an heir of the descendant whose estate is being partitioned. Such a deed is

governed by

Article 1105 of the Civil Code, reading as follows:

o Art. 1105. A partition which includes a person believed to be an heir, but

who is not, shall be void only with respect to such person.

It could be gathered from the pleadings filed by the petitioners that they do not

seek the

nullification of the entire deed of extra-judicial partition but only insofar as the

same deprived

them of their shares in the inheritance from the estate of Teodoro Abenojar;

Should it be proved, therefore, that Severino Abenojar is, indeed, not a legal

heir of Teodoro Abenojar, the portion of the deed of extra-judicial partition

adjudicating certain properties of Teodoro Abenojar in his favor shall be

deemed inexistent and void from the beginning in accordance with Articles

1409, par. (7) and 1105 of the Civil Code. By the express provision of Article

1410 of the Civil Code, the action to seek a declaration of the nullity of the

same does not

prescribe.

m. m. m.

Florencia Bautista

Antera

Mandap

m. HUSBAND

Maxima

Andrada

I I

Severino

Abenojar

(Acknowledged

Natural Child)

Guillerma

Abenojar

(spurious

child)

I

Maria,

Segundo,

Marcial,

Lucio

Teodoro

06 Week. Succession. ALS 3C. 2013. Justice Hofilena.

8

3. MANUEL V FERRER 247 SCRA 476 CARLO SANCHEZ

BENIGNO MANUEL, LIBERATO MANUEL, LORENZO MANUEL, PLACIDA MANUEL,

MADRONA MANUEL, ESPERANZA MANUEL, AGAPITA MANUEL, BASILISA MANUEL,

EMILIA MANUEL AND NUMERIANA MANUEL, PETITIONERS v. Hon. NICODEMO FERRER,

MODESTA BALTAZAR and ESTANISLAOA MANUEL.

August 21, 1995, J. Vitug

FACTS:

1. The MANUELS (Manuels) are the legitimate children of Antonio and Beatriz.

2. Antonio had an extra-marital affair with Ursula Bautista, and he sired JUAN

MANUEL (illegitimate child).

3. JUAN MANUEL married ESPERANZA GAMBA. A certain Laurenciana donated a

parcel of land covering 2,700 m

2

. They also had 2 other parcels of land registered in

Juans name.

4. Juan and Esperanza cant have a child, so they informally adopted private

respondent MODESTA.

5. JUAN made a pacto de retro sale to ESTANISLAOA MANUEL of his land.

6. JUAN died intestate, two years after, ESPERANZA also died.

7. MODESTA executed an affidavit of self-adjudication to issue the title to her name

over the three properties.

8. MODESTA also made a quitclaim as to the pacto de retro sale to ESTANISLAOA.

9. These acts by Modesta did not bode well with the MANUELS.

a. MANUELS filed a case to nullify. The complaint was dismissed holding that

petitioners, not being heirs ab intestato of their illegitimate brother Juan

Manuel, were not the real parties-in-interest to institute the suit.

b. An MR was filed, but was denied.

10. The MANUELS go to the Supreme Court.

ISSUES:

1. Whether or not the legitimate descendants are entitled to the estate of an

illegitimate brother who died without descendants. (NO)

HELD:

1. MANUELS argue that Article 992 applies.

2. Article 992, a basic postulate, enunciates what is so commonly referred to in the

rules on succession as the "principle of absolute separation between the legitimate

family and the illegitimate family." The doctrine rejects succession ab intestato in

the collateral line between legitimate relatives, on the one hand, and illegitimate

relatives, on other hand, although it does not totally disavow such succession in the

direct line. Since the rule is predicated on the presumed will of the decedent, it has

no application, however, on testamentary dispositions.

3. The rule in Article 992 has consistently been applied by the Court in several other

cases. Thus, it has ruled that where the illegitimate child had

half-brothers who were legitimate, the latter had no right to the former's

inheritance;

a. that the legitimate collateral relatives of the mother cannot succeed from

her illegitimate child;

b. that a natural child cannot represent his natural father in the succession

to the estate of the legitimate grandparent;

c. that the natural daughter cannot succeed to the estate of her deceased

uncle who is a legitimate brother of her natural father;

and

d. that an illegitimate child has no right to inherit ab intestato from the

legitimate children and relatives of his father.

4. Indeed, the law on succession is animated by a uniform general intent, and thus no

part should be rendered inoperative by, but must always be construed in relation

to, any other part as to produce a harmonious whole.

Thus, because of the existence of this iron curtain, the petition of the MANUELS are

denied.

4. ROSALES V ROSALES 128 SCRA 69 NORBY

INTESTATE ESTATE OF PETRA V. ROSALES, IRENEA C. ROSALES, petitioner, v.

FORTUNATO ROSALES, MAGNA ROSALES ACEBES, MACIKEQUEROX ROSALES and

ANTONIO ROSALES, respondents. (1987) GERALDEZ

ER: IRENEA seeks to inherit from her mother-in-law. Her husband, a son of the

deceased, predeceased his mother. As such, the court ruled that deceaseds properties

be given to husband, children, and grandchildren (by the predeceasing son). They got

each. IRENEA wants a share too. SC says she cannot get a share, as there are only two

ways to be come compulsory heirs by your own right or by right of representation.

HUSBAND m. Ursula Bautista affair with Antonio m. Beatriz

I I

Esperanza

Gamba

m.

Juan Manuel

(illegitimate

Manuels

(Petitioners)

Informally

adopted

Modesta

Fortunate m. Petra (decedent)

I

Magna Antonio Carterio m.

Irenea (daughter-in-

law)

I

Mackiequerox

06 Week. Succession. ALS 3C. 2013. Justice Hofilena.

9

According to provisions in the code referring to either and both, nowhere can a

daughter-in-law become a compulsory heir, either on her own right or by

representation.

Facts:

1. This is a case filed by a widow of an heir who predeceased his mother. In other

words, the daughter-in-law seeks to be declared a compulsory heir of her

mother-in-law, now that her husband is dead.

2. PETRA was survived by her husband FORTUNATE, her children MAGNA and

ANTONIO, and her grandchild MACIKEQUEROX (son of Carterio)

3. She had another son named CARTERIO, but he died before her.

a. His wife , IRENEA is petitioner here.

4. In the course of Intestate Proceedings, the course ruled as follows:

a. Fortunata (husband), 1/4; Magna (daughter), 1/4; Macikequerox

(grandson), 1/4; and Antonio, son, 1/4.

5. IRENEA wants a share, saying she is a compulsory heir too.

Issue: W/N she is a compulsory heir. No!

Ratio:

Intestate or legal heirs are classified into two (2) groups, namely, those who inherit by

their own right, and those who inherit by the right of representation.

1

Restated, an

intestate heir can only inherit either by his own right, as in the order of intestate

succession provided for in the Civil Code,

2

or by the right of representation provided

for in Article 981 of the same law.

There is no provision in the Civil Code which states that a widow (surviving spouse) is

an intestate heir of her mother-in-law. The provisions of the Code which relate to the

order of intestate succession (Articles 978 to 1014)

1

enumerate with meticulous

1

Art. 980. The children of the deceased shall always inherit from him in their own right, dividing the inheritance

in equal shares.

Art. 981. Should children of the deceased and descendants of other children who are dead, survive, the former

shall inherit in their own right, and the latter by right of representation.

Art. 982. The grandchildren and other descendants shag inherit by right of representation, and if any one of them

should have died, leaving several heirs, the portion pertaining to him shall be divided among the latter in equal

portions.

exactitude the intestate heirs of a decedent, with the State as the final intestate heir.

Petitioner argues that she is a compulsory heir in accordance with the provisions of

Article 887 of the Civil Code which provides that:

Art. 887. The following are compulsory heirs: XXX

(3) The widow or widower; XXX

The aforesaid provision of law

3

refers to the estate of the deceased spouse in which case

the surviving spouse (widow or widower) is a compulsory heir. It does not apply to the

estate of a parent-in-law.

Indeed, the surviving spouse is considered a third person as regards the estate of the

parent-in-law.

It is from the estate of Petra V. Rosales that Macikequerox Rosales draws a share of the

inheritance by the right of representation as provided by Article 981 of the Code.

The essence and nature of the right of representation is explained by Articles 970 and

971 of the Civil Code, viz

Art. 970. Representation is a right created by fiction of law, by virtue of which the

representative is raised to the place and the degree of the person represented, and

acquires the rights which the latter would have if he were living or if he could have

inherited.

Art. 971. The representative is called to the succession by the law and not by the person

represented. The representative does not succeed the person represented but the one

whom the person represented would have succeeded. (Emphasis supplied.)

Article 971 explicitly declares that Macikequerox Rosales is called to succession by law

because of his blood relationship. He does not succeed his father, Carterio Rosales (the

person represented) who predeceased his grandmother, Petra Rosales, but the latter

whom his father would have succeeded. Petitioner cannot assert the same right of

representation as she has no filiation by blood with her mother-in-law.

Art. 999. When the widow or widower survives with legitimate children or their descendants and illegitimate

children or their descendants, whether legitimate or illegitimate, such widow or widower shall be entitled to the

same share as that of a legitimate child.

06 Week. Succession. ALS 3C. 2013. Justice Hofilena.

10

Petitioner however contends that at the time of the death of her husband Carterio

Rosales he had an inchoate or contingent right to the properties of Petra Rosales as

compulsory heir. Be that as it may, said right of her husband was extinguished by his

death that is why it is their son Macikequerox Rosales who succeeded from Petra

Rosales by right of representation. He did not succeed from his deceased father, Carterio

Rosales.

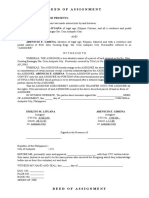

5. BERCILES V GSIS 138 SCRA 53 MAITI

ER:

Judge Berciles died leaving survivors benefits amounting to P311,000 from the

GSIS.

Such benefits are now being claimed by two families, both of whom claim to be the

deceaseds lawful heirs.

GSIS decided that, besides Judge Berciles widow and 4 legitimate children, the

acknowledged natural child and the 3 other illegitimate children shall have a share

in the distribution of the survivors benefits.

Both families opposed this distribution.

WON the distribution by GSIS was in accordance with the law?

No. The disposition made by respondent GSIS of the retirement benefits due the

heirs of the late Judge Pascual G. Berciles is consequently erroneous and not in

accordance with law. Illuminada and her children are the lawful heirs entitled to

the distribution of the benefits which shall accrue to the estate of the deceased

Judge Berciles and will be distributed among the petitioners as his legal heirs in

accordance with the law on intestate succession.

Under the law, Article 287, New Civil Code, illegitimate children other than natural

in accordance with Art. 269 are entitled to support and such successional rights as

are granted in the Code, but for this Article to be applicable, there must be

admission or recognition of the paternity of the illegitimate child.

Article 887, N.C.C., defining who are compulsory heirs, is clear and specific that (i)n

all cases of illegitimate children, their filiation must be duly proved.

FACTS

Judge Pascual G. Berciles of the Court of First Instance of Cebu died in office on

August 21, 1979 at the age of sixty-six years, death caused by cardiac arrest due to

cerebral vascular accident. Having served the government for more than 34 years,

26 years in the judiciary, the late Judge Berciles was eligible for retirement so that

his heirs were entitled to survivors benefits amounting to P311,460.00

Other benefits accruing to the heirs of the deceased consist of the unpaid salary, the

money value of his terminal leave and representation and transportation

allowances, computed at P60,817.52, and the return of retirement premiums paid

by the retiree in the amount of P9,700.00 to be paid by the GSIS.

Such benefits are now being claimed by two families, both of whom claim to be the

deceaseds lawful heirs.

The Illuminada (wife) and the legitimate children filed for survivors benefits which

was duly supported by the required documents

o i.e. marriage certificate

Flor Fuentebella, who also claims to be married to Berciles, the natural child and

the illegitimate children also filed the same claim. As proof of her marriage to

Berciles, the ff were presented:

o Flor claimed that their marriage certificate was destroyed due to the war.

Instead, she presented sworn statements of other people attesting to her

marriage to Berciles

o For the children, a baptismal certificate and certifications that the birth

certificates of the other children were destroyed due to the war.

o Family pictures, letters from Berciles

The retirement benefits were then decided by GSIS to be distributed among the

heirs in the ff manner:

o 77/134 for his widow

o 10/134 for his 4 legitimate children

o 5/134 for his acknowledged natural child

o 4/134 for his 3 illegitimate children

Both families appealed the GSIS decision. Hence this petition

Issue: WON the distribution made by the GSIS was correct?

Held: Accordingly, the disposition made by respondent GSIS of the retirement benefits

due the heirs of the late Judge Pascual G. Berciles is consequently erroneous and not in

accordance with law. Illuminada and her children are the lawful heirs entitled to the

distribution of the benefits which shall accrue to the estate of the deceased

Judge Berciles and will be distributed among the petitioners as his legal heirs in

accordance with the law on intestate succession.

Flor Fuentebella

claims to

be married

to

Judge Pascual

Berciles

m.

Iluminada

Ponce

I

1 ANC + 3

Illegitimate

children

06 Week. Succession. ALS 3C. 2013. Justice Hofilena.

11

Ratio:

The Court, after examination of the evidence presented by both parties, therefore

concludes that Judge Pascual Berciles was legally married to Iluminada Ponce.

His alleged marriage to Flor Fuentebella was not sufficiently proved and therefore

the children begotten with her are either natural or illegitimate children depending

on whether they have been born before or after the marriage of Iluminada Ponce.

o We have examined carefully this birth certificate and We find that the

same is not signed by either the father or the mother; We find no

participation or intervention whatsoever therein by the alleged father,

Judge Pascual Berciles. Under our jurisprudence, if the alleged father did

not intervene in the birth certificate, the putting of his name by the

mother or doctor or registrar is null and void. Such registration would not

be evidence of paternity. The mere certificate by the registrar without the

signature of the father is not proof of voluntary acknowledgment on his

part. A birth certificate does not constitute recognition in a public

instrument.

o As to the baptismal certificate, the rule is that although the baptismal

record of a natural child describes her as a child of the decedent, yet, if in

the preparation of the record the decedent had no intervention, the

baptismal record cannot be held to be a voluntary recognition of

parentage

The SC held the GSISs distribution to be erroneous in view of their ruling the

Chanliongco and Vda. De Consuegra case [Remember Insurance?] that retirement

benefits shall accrue to his estate and will be distributed among his legal heirs in

accordance with the law on intestate succession, as in the case of a life insurance if

no beneficiary is named in the insurance policy, and that the money value of the

unused vacation and sick leave, and unpaid salary form part of the conjugal estate

of the married employee.

The SC also held GSIS as having grave abuse of discretion in approving the

recommendation with regard to the acknowledged natural child and the

illegitimate children, there being no substantial evidence through competent and

admissible proof of acknowledgment by and filiation with said deceased parent as

required under the law.

Under the law, Article 287, New Civil Code, illegitimate children other than natural

in accordance with Art. 269 are entitled to support and such successional rights as

are granted in the Code, but for this Article to be applicable, there must be

admission or recognition of the paternity of the illegitimate child.

Article 887, N.C.C., defining who are compulsory heirs, is clear and specific that (i)n

all cases of illegitimate children, their filiation must be duly proved.

In the Noble case, the Supreme Court laid down this ruling:

o The filiation of illegitimate children, other than natural, must not only be

proven, but it must be shown that such filiation was acknowledged by the

presumed parent. If the mere fact of paternity is all that needs to be

proven, that interpretation would pave the way to unscrupulous

individuals to take advantage of the death of the presumed parent, who

would no longer be in a position to deny the allegation, to present even

fictitious claims and expose the life of the deceased to inquiries affecting

his character.

26. ARTS. 1003 1014

SUBSECTION 5. - Collateral Relatives

Art. 1003. If there are no descendants, ascendants, illegitimate children, or a surviving

spouse, the collateral relatives shall succeed to the entire estate of the deceased in

accordance with the following articles. (946a)

Art. 1004. Should the only survivors be brothers and sisters of the full blood, they shall

inherit in equal shares. (947)

Art. 1005. Should brothers and sisters survive together with nephews and nieces, who

are the children of the descendant's brothers and sisters of the full blood, the former

shall inherit per capita, and the latter per stirpes. (948)

Art. 1006. Should brother and sisters of the full blood survive together with brothers

and sisters of the half blood, the former shall be entitled to a share double that of the

latter. (949)

Art. 1007. In case brothers and sisters of the half blood, some on the father's and some

on the mother's side, are the only survivors, all shall inherit in equal shares without

distinction as to the origin of the property. (950)

Art. 1008. Children of brothers and sisters of the half blood shall succeed per capita or

per stirpes, in accordance with the rules laid down for the brothers and sisters of the full

blood. (915)

Art. 1009. Should there be neither brothers nor sisters nor children of brothers or

sisters, the other collateral relatives shall succeed to the estate.

The latter shall succeed without distinction of lines or preference among them by reason

of relationship by the whole blood. (954a)

Art. 1010. The right to inherit ab intestato shall not extend beyond the fifth degree of

relationship in the collateral line. (955a)

SUBSECTION 6. - The State

06 Week. Succession. ALS 3C. 2013. Justice Hofilena.

12

Art. 1011. In default of persons entitled to succeed in accordance with the provisions of

the preceding Sections, the State shall inherit the whole estate. (956a)

Art. 1012. In order that the State may take possession of the property mentioned in the

preceding article, the pertinent provisions of the Rules of Court must be observed.

(958a)

Art. 1013. After the payment of debts and charges, the personal property shall be

assigned to the municipality or city where the deceased last resided in the Philippines,

and the real estate to the municipalities or cities, respectively, in which the same is

situated.

If the deceased never resided in the Philippines, the whole estate shall be assigned to the

respective municipalities or cities where the same is located.

Such estate shall be for the benefit of public schools, and public charitable institutions

and centers, in such municipalities or cities. The court shall distribute the estate as the

respective needs of each beneficiary may warrant.

The court, at the instance of an interested party, or on its own motion, may order the

establishment of a permanent trust, so that only the income from the property shall be

used. (956a)

Art. 1014. If a person legally entitled to the estate of the deceased appears and files a

claim thereto with the court within five years from the date the property was delivered

to the State, such person shall be entitled to the possession of the same, or if sold the

municipality or city shall be accountable to him for such part of the proceeds as may not

have been lawfully spent. (n)

1. CITY OF MANILA V ARCHBISHOP OF MANILA 36 PHIL 815 LEX AQUINO

THE CITY OF MANILA, petitioner-appellant, v. THE ROMAN CATHOLIC ARCHBISHOP

OF MANILA and THE ADMINISTRATOR FOR THE ESTATE OF MARIA CONCEPCION

SARMIENTO, interveners-appellees. G.R. No. L-10033; August 30, 1917

ER: Ana Sarmiento died in 1672. She left a will providing for the establishment of a

"Capellania de Misas;" and that the first chaplain of said capellania should be her nephew

Pedro del Castillo. The succeeding administration should continue perpetually. For more

than two hundred years, the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Manila, through his various

agencies, has administered the property. An action was commenced in CFI Manila

seeking to escheat the property. SC held that the property cannot be escheated. Section

750 of Act No. 190 provides when property may be declared escheated. It provides,

"when a person dies intestate, seized of real or personal property . . . leaving no heir or

person by law entitled to the same". Ana Sarmientos will clearly, definitely and

unequivocally defines and designates what disposition shall be made of the property in

question.

Facts:

Ana Sarmiento resided, with her husband, in the city of Manila.

17th day of November, 1668: she made a will.

23d day of November, 1668: she added a codicil.

19th day of May, 1669: she made another will and made the November 23 codicil a

part thereof.

The will contained provisions for the establishment of a "Capellania de Misas;" that

the first chaplain of said capellania should be her nephew Pedro del Castillo;

o There was a provision for the administration of said property in relation

with the said "Capellania de Misas" that the succeeding administration

should continue perpetually.

Ana Sarmiento died about the year 1672.

For more than two hundred years the intervener, the Roman Catholic Archbishop of

Manila, through his various agencies, has administered the property;

o They claim that the institution has rightfully and legally succeeded in

accordance with the terms and provisions of the will of Ana Sarmiento.

This action was commenced CFI Manila on February 15, 1913. Its purpose was to

have declared escheated to the city of Manila the property which consists of five

parcels of land located on of Malate and Paco.

The theory of the City of Manila is that Ana Sarmiento was the owner of said

property and died in the year 1668 without leaving "her or person entitled to the

same."

The Honorable A. S. Crossfield, reached the conclusion that the prayer of the City of

Manila should be denied. Manila appealed.

Issue: Whether or not Ana Sarmientos property could be escheated to the City of

Manila.

Held: The property cannot be escheated.

Ratio:

Section 750 of Act No. 190 provides when property may be declared escheated.

It provides, "when a person dies intestate, seized of real or personal property . . .

leaving no heir or person by law entitled to the same,"

In that case, such property under the procedure provided for, may de declared

escheated.

06 Week. Succession. ALS 3C. 2013. Justice Hofilena.

13

The proof shows that Ana Sarmiento did not die intestate. She left a will. The will

provides for the administration of said property by her nephew as well as for the

subsequent administration of the same.

It further shows that she did not die without leaving a person by law entitled to

inherit her property. In view of the facts, therefore, the property in question

cannot be declared escheated.

If by any chance the property may be declared escheated, it must be based upon the

fact that persons subsequent to Ana Sarmiento died intestate without leaving heir

or person by law entitled to the same.

The will clearly, definitely and unequivocally defines and designates what

disposition shall be made of the property in question. The heir mentioned in said

will evidently accepted its terms and permitted the property to be administered in

accordance therewith.

So far as the record shows, it is still being administered in accordance with the

terms of said will for the benefit of the real beneficiary, as was intended by the

original owner.

2. ADLAWAN V ADLAWAN 479 SCRA 275 (JAN 2006) DONDON

Arnelito Adlawan v. Emeterio and Narcisa Adlawan

Emergency Recitation:

DOMINADOR Adlawan died leaving behind his wife GRACIANA and acknowledged

illegitimate son ARNELITO

Part of the estate of DOMINADOR was his ancestral house and lot which were

transferred to him by his parents though a simulated deed of sale while the latter

were still alive in order for DOMINADOR to obtain a loan with the property as

collateral and use to renovate the house

DOMINADOR, despite being the title owner, did not question the ownership of his

parents over the property, and in fact his entire family (including his 9 siblings, 2 of

which are EMTERIO and NARCISA) continued to live there

When DOMINADOR died, ARNELITO claimed to be the sole heir and executed an

affidavit adjudicating to himself the property. He then asked his dads siblings,

EMETERIO and NARCISA to vacate the property, claiming that he merely tolerated

their stay there on the condition that they will leave when he decides to use the

property

EMETERIO and NARCISA refused to leave and instead filed an action to quiet title

Hence, ARNELITO filed the present ejectment case against them

ISSUE: W/N the ejectment case can prosper NO it cannot. SC dismisses ejectment

case!

ARNELITO is wrong in claiming to be the sole heir because when DOMINADOR died,

he was also survived by his wife, GRACIANA. Hence, by intestate succession,

GRACIANA became a co-owner of the property left behind by DOMINADOR

True the Civil Code provides that any co-owner may bring an action for ejectment,

but this cannot apply when the person bringing the suit does not recognize the co-

ownership.

ARNELITO clearly claims to bring the ejectment suit as the sole heir and not for the

benefit of the other co-owners (namely, GRACIANAs nephews and nieces who also

have a claim)

Thus, in order for the court to have jurisdiction, these other parties-in-interest must

be impleaded

For failing to do so, the case should be properly dismissed.

FACTS:

History: RAMON and OLIGIA ADLAWAN owned Lot 7226 and the house built

thereon, located at Barrio Lipata, Cebu

1961 RAMON and OLIGIA needed money to renovate their house but they were

not qualified to obtain a loan. Hence, they transferred the property to their only

child (among their 9 children) who earned a college education, DOMINADOR,

through a simulated deed of sale

DOMINADOR took out a loan with the property as collateral and got the house

renovated

Throughout the subsequent years, although the title was under his name,

DOMINADOR did not question the ownership of his parents and in fact, his parents

still lived in the house along with his other siblings (including respondents here

EMETERIO Adlawan and NARCISA Adlawan)

May 28, 1987 DOMINADOR died leaving his wife GRACIANA and acknowledged

illegitimate son, ARNELITO

ARNELITO claimed that he is the sole heir of DOMINADOR and executed an affidavit

adjudicating to himself Lot 7226 and the house built thereon

He claims now that he merely allowed DOMINADORs brothers and sisters

(EMETERIO and NARCISA) to live in the property on the condition that they will

vacate when he decides to use it

He now demanded them to leave but they refused to do so.

Hence, he now files an ejectment case against them

EMETERIO and NARCISA claim: ARNELITO cannot bring the ejectment case because

the property is not solely his. That when DOMINADOR died, he also left his wife

GRACIANA who was entitled to her own share of the property. Also, they

questioned ARNELITOs status claiming that DOMINADORs signature in

ARNELITOs birth certificate was forged

MTC dismissed the ejectment case stating that ARNELITOs status and the

settlement of DOMINADORs estate were conditions precedent to the ejectment

case

RTC reversed MTC ruling on the ground that DOMINADORs title over the land

cannot be collaterally attacked

RTC also granted ARNELITOs motion for execution pending appeal but now

nephews and nieces of GRACIANA seek to intervene to protect their interest. RTC

dismissed this motion to intervene

06 Week. Succession. ALS 3C. 2013. Justice Hofilena.

14

RTC however also eventually recalled the order granting the execution pending

appeal because the case was already elevated to the CA

CA reversed RTC and reinstated MTC decision dismissing the ejectment case

Hence, this petition

ISSUE: W/N the ejectment case can prosper NO it cannot

HELD: Petition denied. Ejectment case dismissed.

RATIO:

The ejectment case cannot prosper because the same theory of succession which

ARNELITO bases his claim for ownership over the property in fact reveals that he is not

the sole owner.

This is so because DOMINADOR was survived not only by petitioner but also by his legal

wife, GRACIANA, who died 10 years after the demise of DOMINADOR.

By intestate succession, GRACIANA and petitioner became co-owners of Lot 7226. The

death of GRACIANA on May 6, 1997, did not make petitioner the absolute owner of Lot

7226 because the share of GRACIANA passed to her relatives by consanguinity and not

to petitioner with whom she had no blood relations.

ARNELITO now claims that he can institute the ejectment case based on Article 487 of

the Civil Code which provides:

ART. 487. Any one of the co-owners may bring an action in ejectment.

However, this will only apply if the co-heir does not bring the suit solely for his own

benefit. It cannot apply when the person bringing the suit does not recognize the co-

ownership.

The renowned civilist, Professor Arturo M. Tolentino, explained

A co-owner may bring such an action, without the necessity of joining all the other

co-owners as co-plaintiffs, because the suit is deemed to be instituted for the

benefit of all. If the action is for the benefit of the plaintiff alone, such that he

claims possession for himself and not for the co-ownership, the action will not

prosper.

If the action is for the benefit of the plaintiff alone who claims to be the sole owner and

entitled to the possession thereof, the action will not prosper unless he impleads the

other co-owners who are indispensable parties.

In this case, the respondent alone filed the complaint, claiming sole ownership over the

subject property and praying that he be declared the sole owner thereof. There is no

proof that the other co-owners had waived their rights over the subject property or

conveyed the same to the respondent or such co-owners were aware of the case in the

trial court.

Also, under Section 7, Rule 3 of the Rules of Court, the respondent was mandated to

implead his siblings, being co-owners of the property, as parties. The respondent failed

to comply with the rule. It must, likewise, be stressed that the Republic of the

Philippines is also an indispensable party as defendant because the respondent sought

the nullification of OCT No. P-16540 which was issued based on Free Patent No. 384019.

Unless the State is impleaded as party-defendant, any decision of the Court would not be

binding on it. It has been held that the absence of an indispensable party in a case

renders ineffective all the proceedings subsequent to the filing of the complaint

including the judgment. The absence of the respondents siblings, as parties, rendered all

proceedings subsequent to the filing thereof, including the judgment of the court,

ineffective for want of authority to act, not only as to the absent parties but even as to

those present

Clearly, the said cases find no application here because petitioners action operates as a

complete repudiation of the existence of co-ownership and not in representation or

recognition thereof. Dismissal of the complaint is therefore proper.

27. ARTS. 1015 1023 MEMORIZE ART. 1015

CHAPTER 4

PROVISIONS COMMON TO TESTATE AND INTESTATE SUCCESSIONS

SECTION 1. - Right of Accretion

MEMORIZE Art. 1015. Accretion is a right by virtue of which, when two or more

persons are called to the same inheritance, devise or legacy, the part assigned to

the one who renounces or cannot receive his share, or who died before the

testator, is added or incorporated to that of his co-heirs, co-devisees, or co-

legatees. (n)

Art. 1016. In order that the right of accretion may take place in a testamentary

succession, it shall be necessary:

(1) That two or more persons be called to the same inheritance, or to the same

portion thereof, pro indiviso; and

(2) That one of the persons thus called die before the testator, or renounce the

inheritance, or be incapacitated to receive it. (928a)

Art. 1017. The words "one-half for each" or "in equal shares" or any others which, though

designating an aliquot part, do not identify it by such description as shall make each heir

the exclusive owner of determinate property, shall not exclude the right of accretion.

06 Week. Succession. ALS 3C. 2013. Justice Hofilena.

15

In case of money or fungible goods, if the share of each heir is not earmarked, there shall

be a right of accretion. (983a)

Art. 1018. In legal succession the share of the person who repudiates the inheritance

shall always accrue to his co-heirs. (981)

Art. 1019. The heirs to whom the portion goes by the right of accretion take it in the

same proportion that they inherit. (n)

Art. 1020. The heirs to whom the inheritance accrues shall succeed to all the rights and

obligations which the heir who renounced or could not receive it would have had. (984)

Art. 1021. Among the compulsory heirs the right of accretion shall take place only when

the free portion is left to two or more of them, or to any one of them and to a stranger.

Should the part repudiated be the legitime, the other co-heirs shall succeed to it in their

own right, and not by the right of accretion. (985)

Art. 1022. In testamentary succession, when the right of accretion does not take place,

the vacant portion of the instituted heirs, if no substitute has been designated, shall pass

to the legal heirs of the testator, who shall receive it with the same charges and

obligations. (986)

Art. 1023. Accretion shall also take place among devisees, legatees and usufructuaries

under the same conditions established for heirs. (987a)

1. TORRES V LOPEZ 49 PHIL 504 PENDIX

In the matter of the estate of Tomas Rodriguez, deceased.

MANUEL TORRES, special administrator, and LUZ LOPEZ DE BUENO, heir, appellee,

vs. MARGARITA LOPEZ, opponent-appellant.

G.R. No. L-25966; November 1, 1926

Emergency Recit:

Tomas Rodriguez was in the custody of his cousin Vicente Lopez, since he was senile and

infirm. Tomas excuted a last will and testament, declaring Lopez and de Bueno as

universal heirs. However, Lopez had not presented his final accounts as guardian, and

no account was presented to him at the time of his death making the disposition of

Tomas to Lopez invalid under Art. 753(Old Civil Code).

The will was already probated in a previous case, but Margarita Lopez (Margarita)

wanted a piece of the pie, so she wanted to get Vicente's portion. The matter that the SC

decided in this case was who had the right to Lopez' disqualified share, de Bueno or

Margarita? De Bueno! Why? The Court applied Art. 982 (now 1015) defining accretion.

Accretion occurs when

Two or more persons are called to the same inheritance without special

designation of shares.

One of the persons so called dies before the testator, or renounces the

inheritance or is disqualified to receive it.

Lopez and de Bueno were called to the same inheritance without special designation of

shares. Furthermore, Lopez had predeceased the testator and was disqualified to

receive the estate even if he had been alive at the time of the testator's death. The legal

effect would be to give to the survivor, Luz Lopez de Bueno, not only the undivided

half which she would have received in conjunction with her father if he had been

alive and qualified to take, but also the half which pertained to him.

Margarita attempted to assert her claim by invoking two articles. First Art. 764, which

stated that a will can be valid even if the instituted heir was disqualified. AND Art. 912,

which stated that legal succession takes place if the heir dies before the testator and also

when the heir instituted is disqualified to succeed. The SC denied her claim stating that if

there are conflicting provisions, the more general is to be considered as being limited by

the more specific. As between articles 912 and 983 (1015), 912 is the more general

of the two since it is about the general topic of intestate succession while

983(1015) is more specific, defining the particular conditions under which

accretion takes place.

Indeed, in Art. 912(3) the provision with respect to intestate succession is expressly

subordinated to Art. 983 by the expression "and (if) there is no right of accretion."

2

Facts:

Rodriguez was both physically weak and senile, so he was placed in the custody of his

cousin, Vicente Lopez. Rodriguez executed his last will and testament on Jan 3, 1924,

declaring as universal heir the aforementioned Lopez and the latter's daughter, Luz

Lopez de Bueno. However, on Jan 7, 1924 Lopez died, and Rodriguez died as well on

February 25, 1924. At the time the will was made Vicente F. Lopez had not

presented his final accounts as guardian, and no such accounts had been

presented by him at the time of his death. The will was contested by Margarita Lopez,

Vicente's nearest relative. The will was admitted probate in a previous case.

Issue: Who, between de Bueno and Margarita, has the better right to Vicente's share?

2

May other defense pa yung abogado ni Margarita, distinguishing the right incapcity to succeed v. incapacity to

take (912 v. 982). Argument nila incapcity to succeed daw yung case, so 912 applies. Court rejected the

contention again. Discussed siya sa main digest.

06 Week. Succession. ALS 3C. 2013. Justice Hofilena.

16

Held: De Bueno has the better right! The judgment appealed from will be affirmed, and

it is so ordered, with costs against the appellant.

Ratio:

There are two intermingling issues in the case. First was Art. 753 of the Old Civil Code

declared that, with certain exceptions in favor of near relatives, no testamentary

provision shall be valid when made by a ward in favor of his guardian before the

final accounts of the latter have been approved. This was applied by the SC in this

case. Thus, the disposition of Rodriguez to Lopez was not an exception under the law.

The court then applied Art. 982 (now 1015) to the case, which defined the right of

accretion. In effect, accretion take place in a testamentary succession when:

First: the two or more persons are called to the same inheritance or the

same portion thereof without special designation of shares; and

second: one of the persons so called dies before the testator or renounces

the inheritance or is disqualified to receive it.

Lopez and de Bueno were called to the same inheritance without special designation of

shares. Furthermore, Lopez had predeceased the testator and was disqualified to

receive the estate even if he had been alive at the time of the testator's death. The legal

effect would be to give to the survivor, Luz Lopez de Bueno, not only the undivided

half which she would have received in conjunction with her father if he had been

alive and qualified to take, but also the half which pertained to him. There was no

error whatever, therefore, in the order of the trial court declaring Luz Lopez de Bueno

entitled to the whole estate. It correctly applied Art. 982(1015).

To assert her better right to the Vicente's portion, Margarita invoked two articles:

Art. 764 of the Old Civil Code which declared, among other things, that a will

may be valid even though the person instituted as heir is disqualified to inherit.

Art. 912 which stated that legal succession takes place if the heir dies before

the testator and also when the heir instituted is disqualified to succeed.

The SC denied her contention. If there are conflicting provisions, the more general is to

be considered as being limited by the more specific. As between articles 912 and 983

(1015), 912 is the more general of the two since it is about the general topic of

intestate succession while 983(1015) is more specific, defining the particular

conditions under which accretion takes place. Indeed, in Art. 912(3) the provision

with respect to intestate succession is expressly subordinated to Art. 983 by the

expression "and (if) there is no right of accretion."

Indeed, in Art. 912(3) the provision with respect to intestate succession is expressly

subordinated to Art. 983 by the expression "and (if) there is no right of accretion." It

is true that the same express qualification is not found in Art. 912(4), yet it must be so

understood, in view of the rule of interpretation above referred to, by which the more

specific is held to control the general. Besides, this interpretation supplies the only

possible means of harmonizing the two provisions.

Margarita's attorneys direct attention to the fact that, under Art. 912(4), intestate

succession occurs when the heir instituted is disqualified to succeed (incapaz de

suceder), while, under 982(2) accretion occurs when one of the persons called to inherit

under the will is disqualified to receive the inheritance (incapaz de recibirla).

A distinction is then drawn between incapacity to succeed and incapacity to take,

and it is contended that the disability of Vicente F. Lopez was such as to bring the

case under article 912 rather than 982. The SC denied such technical interpretation

of the code. At any rate, the disability of Vicente Lopez was not a general disability

to succeed but an accidental incapacity to receive the legacy, a consideration

which makes a case for accretion rather than for intestate succession.

28. ARTS. 1024 1028

SECTION 2. - Capacity to Succeed by Will of by Intestacy

Art. 1024. Persons not incapacitated by law may succeed by will or ab intestato.

The provisions relating to incapacity by will are equally applicable to intestate

succession. (744, 914)

Art. 1025. In order to be capacitated to inherit, the heir, devisee or legatee must be living

at the moment the succession opens, except in case of representation, when it is proper.

A child already conceived at the time of the death of the decedent is capable of

succeeding provided it be born later under the conditions prescribed in article 41. (n)

Art. 1026. A testamentary disposition may be made to the State, provinces, municipal

corporations, private corporations, organizations, or associations for religious, scientific,

cultural, educational, or charitable purposes.

All other corporations or entities may succeed under a will, unless there is a provision to

the contrary in their charter or the laws of their creation, and always subject to the

same. (746a)

Art. 1027. The following are incapable of succeeding:

06 Week. Succession. ALS 3C. 2013. Justice Hofilena.

17

(1) The priest who heard the confession of the testator during his last illness,

or the minister of the gospel who extended spiritual aid to him during the same

period;

(2) The relatives of such priest or minister of the gospel within the fourth

degree, the church, order, chapter, community, organization, or institution to

which such priest or minister may belong;

(3) A guardian with respect to testamentary dispositions given by a ward in his

favor before the final accounts of the guardianship have been approved, even if

the testator should die after the approval thereof; nevertheless, any provision

made by the ward in favor of the guardian when the latter is his ascendant,

descendant, brother, sister, or spouse, shall be valid;