Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Kuttanad: Meaning Low Lying Lands' Is One of The Most Fertile Regions of The World Spread

Загружено:

strshirdiИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Kuttanad: Meaning Low Lying Lands' Is One of The Most Fertile Regions of The World Spread

Загружено:

strshirdiАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Kuttanad meaning low lying lands is one of the most fertile regions of the world spread

over the district of Alappuzha, Kottayam & Pathanamthitta which is crisscrossed by rivers,

canals & waterways. our ma!or rivers namely Achen"oil, Pampa, #animala & #eenachil

originating from the $igh %anges discharge their water into the Arabian sea through the

Kuttanad region.

&he Kuttanad 'etland (ystem )K'(* inclusive of the +embanad la"e is now receiving global

attention because nature is at the pea" of its beauty in this %amsar site. &he K'( comprising

of ,- Panchayats of Alappuzha district, -. Panchayats of Kottayam district and / Panchayats

of Pathanamthitta district is a predominantly agriculture belt of Kerala where people are

dependent on farming & allied sectors li"e fishing, animal husbandry etc for their livelihood.

&his is the only part of the world where rice is cultivated below sea level and this will be of

great importance in view of the pro!ected sea level rise caused by global warming. 0t is a

uni1ue wetland which permits one good crop of rice and one harvest of fish and an area of

thriving water tourism. Kuttanad is a biodiversity paradise. &he area is also popular for its

coconut cultivation, duc" rearing & coir industry.

#.(. (waminathan research foundation research conducted a scientific study of the region

and suggested suitable measures to mitigate agrarian distress in "uttanad. &his was accepted

by 2o0 for funding under central sector schemes.

3essons from the 4urban conference

Indias objectives:

0ndia had gone to 4urban with three predominant ob!ectives.

5.* &o secure the continuance of the Kyoto Protocol, whose first commitment period6 is

scheduled to end in -75-.

-.* (econd, to ensure that its particular concerns on e1uity, intellectual property rights

and unilateral trade measures, neglected in previous negotiating rounds, were

substantively integrated in the future climate agenda.

,.* And third, to preserve the notion of differentiation6 between developed and

developing countries, recognised through the principle of common but

differentiated responsibilities6 )894%* in both the :.;. ramewor" 8onvention on

8limate 8hange ):;888* and the 5<<- %io 4eclaration on =nvironment and

4evelopment.

But what happened at Durban:

&he continuation of the Kyoto Protocol, important as it may be, offers little more than an

ephemeral gain. 'ith the :nited (tates refusing to ratify the treaty> 8anada blatantly

disregarding its previous ratification> and ?apan, Australia and %ussia e1ually disinclined

towards it, it is only the =uropean :nion6s commitment at 4urban that has still "ept the

Protocol alive. 9ut it is unli"ely to survive in its current form beyond this e@tended phase.

And, going by past record, its ability to enforce serious emission reductions in developed

countries also remains e1ually dim.

'hat 0ndia gave up in return at 4urban however holds far more serious conse1uences. &he

most important decision that Parties too" at 4urban was to terminate the ongoing

negotiating process on 3ongAterm 8ooperative Action6 )38A* that had been launched under

the 9ali Action Plan in -77., by the end of -75-. Adopted following tough negotiations, this

had notably maintained the firewall6 between developed and developing countries and also

the lin"ing clause6 that had made mitigation by the latter contingent on the level of

technological and financial support that they received from the former.

Copenhagen & Cancun

&he -77< 8openhagen Accord and the -757 8ancun Agreements were both negotiated under

this mandate. =ven though they diluted the 9ali firewall6, they nevertheless reaffirmed the

core :;888 norms, that nations would need to combat climate change on the basis of

e1uity6 and in accordance with the 894% principle, respecting the various provisions of the

8onvention.

&he new decision at 4urban that now replaces the 38A negotiating trac" with the 4urban

Platform for =nhanced Action6 remar"ably fails to ma"e even a passing reference to these

foundational principles. 8alling instead for the widest possible cooperation by all countries,6

a preferred formulation of the 'est, it launches a new process to develop a protocol, another

legal instrument or an agreed outcome with legal force6 by -75/, which is to be applicable to

all Parties6, and enter into force from -7-7. 9ut the fact that a "ey decision was adopted for

the first time in the entire -7Ayear history of international climate tal"s without even a

cursory mention of e1uity6 and 894% should give policyma"ers in ;ew 4elhi serious pause.

&his was a successful attempt by the developed world to detach the future climate

negotiations from their e@isting normative moorings, and to revise the very basis on which

their legal obligations, and the legitimacy of the positions and arguments of countries li"e

0ndia, have so far been based.

0ndia also failed in its bid to gain substantive recognition for the issues of intellectual

property rights and unilateral trade measures. =ven on e1uity6, the issue closest to its heart,

all that it managed to secure in the end is a wor"shop6 on e1uitable access to sustainable

development6, itself an ambiguous formulation, under a mandate that is now scheduled to

e@pire. &o what e@tent e1uity6 will find any formal operational recognition beyond -75-

remains an open 1uestion.

So What should India do now:

&he outcome of the 4urban conference B and 0ndia6s failure to attain most of its stated

ob!ectives B should now raise serious 1uestions about the wisdom of its negotiating strategy,

and especially its alliance management. 0t should also raise 1uestions about the capacity that

it has brought to bear in these negotiations to date. At 4urban, 0ndia fielded a delegation of

,C members, as opposed to <D from the :.(., 575 from the =:, --E from 9razil, 5D. from

8hina, and even 57- from 9angladesh. And insiders well "now what the teethAtoAtail ratio

even within this small group is. &here could be more slippages in the future unless this

capacity constraint is urgently, and meaningfully, addressed.

0f the interests of 5.- billion 0ndians are to be ade1uately safeguarded in the coming decade

and beyond, it is imperative that 0ndia develops both a coherent grand strategy to address

climate change that en!oys broad crossAparty parliamentary support, and a strong

negotiating team to see it through.

4urban is a wa"eAup call that it must not ignore.

Rio + 20 :

Developed countries pledge no funds; EU feels it was a waste of tie! India remains

disappointed with the wea" political will in developed countries to provide enhanced means

of implementation to developing countries. 'e are glad that we have agreed to set up two

important mechanisms, one for &echnology &ransfer and another for inance. 9oth were

0ndian proposals.

So thats the story from Rio victory in principles and standstill in practice.

It is, where it was.

%ioF-7 =arth (ummit B which was tas"ed with shaping a route for the world to reduce

poverty, advance social e1uity and ensure environmental protection B failed to achieve

anything substantial. $owever, strictly spea"ing from 0ndia6s corner, feel that the outcome in

%io de ?aneiro was not all that negative.

$ere is whyG first, due to 0ndia6s persistence, the important and nonAnegotiable principle of

common but differentiated responsibilities B the recognition that rich countries grew by

polluting and the emerging world cannot be forced to bear the cost of green development B

was brought bac" into the environmental discourse> and second, no timeAbound specific

targets were thrust on the developing world. ;either of the two came easily thoughG the

developed world, especially the =uropean :nion, had pushed for a oneAsizeAfitsAall green

agenda and advocated targets on environmental themes while diluting its own

responsibilities towards a greener, cleaner world.

0mportant proposals such as providing universal energy access and doubling renewables by

-7,7 were left untouched. 8onference will also be remembered for "ic"Astarting the process

on (ustainable 4evelopment 2oals. 0ndia6s position has been that the (42s should be

aspirational and nonAbinding , based on the principles of e1uity and 894%, and should not

impinge on 0ndia6s domestic policy space.

SDG

&he (42s could provide a logical se1uence and structure to the process launched almost -7

years agoG

in 5<<- the guiding principles were agreed to as well as a road map for sustainable

development>) Agenda -5 A is an action plan of the :nited ;ations ):;* for the -5

st

century

related to sustainable development and was an outcome of the :nited ;ations 8onference on

=nvironment and 4evelopment ):;8=4* held in %io de ?aneiro, 9razil, in 5<<-.*

in -77- a Plan of 0mplementation was defined>) World Summit on Sustainable

Development, '((4 or Earth Summit 2002 laid out the ?ohannesburg Plan of

0mplementation as an action plan*

and now in -75- we could consider identifying goals in order to better identify gaps and

needs and provide for more structured implementation of the principles and goals defined -7

years ago.

Hb!ectives agreed to internationally could eventually be underpinned by targets I as is the

case with the #42s A that reflect the realities and priorities at national levels. &hey would

thus be fully aligned with national conte@ts and could therefore be a useful tool for guiding

public policies.

&he (42s would play an important role in the identification of gaps and needs in countries,

for e@ample in terms of means of implementation, institutional strengthening, and capacity

building to increase absorptive capacity for new technologies.

4efined internationally, li"e the #42s, these would serve both for comparing results as well

as furthering opportunities for cooperation, including (outhA(outh cooperation.

(425 (ustainable 8onsumption and Production

(42- (ustainable livelihoods, youth & education

(42, 8limate sustainability

(42C 8lean energy

(42/ 9iodiversity

(42D 'ater

(42. $ealthy seas and oceans

(42E $ealthy forests

(42< (ustainable agriculture

(4257 2reen cities, (ustainable cities

(4255 (ubsidies and investment

(425- ;ew 0ndicators of progress

(425, Access to information

(425C Public participation

(425/ Access to redress and remedy

(425D =nvironmental !ustice for the poor and marginalized

(425. 9asic health

0mproved resilience and disaster preparedness

%ioF-7 has made wea" references to the human right to water, empowerment of women, the

poor, indigenous people, disabled and vulnerable groups, belying e@pectations of stronger

support. 'hat is important is for 0ndia and other fastAgrowing nations to invest heavily in

human capital to help such citizens, notably in education and health, and preserve its stoc"

wealth. 0t must also start producing data on sustainability indicators, such as polluting

emissions, nutrient overload in water bodies, health of select natural species, habitat

conversion, and fish stoc"s. &hat can ma"e development sustainable.

DE !"#!

2eoAengineering options include adding sunAreflecting chemicals to the upper atmosphere to

mimic the effect of big volcanic eruptions that mas" the sun, or fertilising the oceans to

promote the growth of algae that soa" up carbon from the air.

Among other ideas, a giant mirror could be placed in space to bloc" some sunlight or sea

spray could be in!ected into the air to create clouds whose white tops would reflect sunlight.

&hese have received enthusiasm at :; .

Contentious issues at Doha CO !" # Dec 20!2

5. ;o clear road map of action in terms of ambitious emission cuts from developed

countries or

-. A $inancial commitment for adaption or loss and damage.

,. &he issue of surplus emissions is not addressed, and

C. the length o$ second commitment to the Kyoto Protocol is left vague A from five to

eight years.

/. &he tric"y zone of intellectual property rights %&R' in relationship (ith

technolog) transfer remains vague.

D. Also in dispute is Jhot airK, the name given to =arthAwarming greenhouse gas emission

1uotas that countries were given under the first leg of the 5<<. Kyoto Protocol and did

not use B some 5, billion tonnes in total. &he credits can be sold to nations battling to

meet their own 1uotas, meaning greenhouse gas levels decrease on paper but not in the

atmosphere. Agreement on hot air is "ey to the 4oha delegates e@tending the life of the

Kyoto pact, the world s only binding pact on curbing greenhouse gases, whose first leg

e@pires on 4ecember ,5.

.. A new -7-7 deal, due to be finalised by -75/, will include commitments for all the

nations of the world. &he duration of an interim *second commitment periodK of

Kyoto is also in contention.

E. &he big battle is over e+uit) and common but di$$erentiated responsibilit), the

principles of e1uity, shared vision.

What is the ,D-

&he Ad $oc 'or"ing 2roup on the 4urban Platform for =nhanced Action )A4P* is a

subsidiary body that was established by decision 5L8P.5. to develop a protocol, another legal

instrument or an agreed outcome with legal force under the 8onvention applicable to all

Parties. &he A4P is to complete its wor" as early as possible but no later than -75/ in order

to adopt this protocol, legal instrument or agreed outcome with legal force at the twentyAfirst

session of the 8onference of the Parties and for it to come into effect and be implemented

from -7-7.

&ndia.s response to climate change

Hver the last decade or so, 0ndias emissions B which now ma"e up five per cent of

global emissions, the third highest in the world B have displayed a clear shift from

agriculture, where rice cultivation and livestoc" contribute to methane production.

Hn the other hand, the energy and industrial sectors, which mostly produce carbon

dio@ide, now hold an increasing share of the total.

9etween 5<<C and -77., the yearAonAyear growth rate of agriculture emissions was only 7.D

per cent. =missions from the energy sector grew at a rate of C.E per cent over the same

period.

=ven though starting from a low base, emissions from waste have also risen sharply B seeing

a .., per cent growth rate between 5<<C and -77. B with urbanisation generating everA

larger 1uantities of municipal waste.

&he estimates for -77. show that the energy sector B including power, transport and

residential electricity B was responsible for /E per cent of 0ndias emissions, with industry

and agriculture following at -- and 5. per cent.

the government launched the ;ational Action Plan on 8limate 8hange );AP88* in

-77E. =ight national missions B dealing with solar energy, energy efficiency,

sustainable agriculture and habitats, water and forestry, the $imalayan ecosystem

and research B were charted under the plan.

&he two missions on mitigation B solar energy and energy efficiency B are more

sharply defined, but if you loo" at something as large and complicated as the

agriculture mission, it loo"s as though it was !ust rolled out hastily in time for Mthe

critical -77< :; summit atN 8openhagen without sufficient thought

0ndias energy losses in distribution and transmission are huge. &hat needs to be

addressed much more.

;AP88 stresses a lowerAcarbon model of the e@isting development path. J'e have

the opportunity to reAimagine our development pathway. or e@ample, urban

planning needs to revolve round nonAmotorised transport.K

%enewable energy B which stands at -E,777 #' today B is being propelled by mar"et

forces. 3oo" at the wind energy sector in &amil ;adu. 0t is being promoted by the te@tile

industry simply because it is a cheaper source of energy. 0f the government can galvanise

these mar"et forces, it could ma"e a bigger difference than regulatory regimes such as the

PA& scheme.

the solar and energyAefficiency missions as those which have started bearing fruit. JOou have

to realise that missions li"e agriculture and water are longAterm adaptation missions.K

2iven that the missions were launched in -77E and were planned to run till -75., they have

almost reached the halfway point.

$owever, the Prime #inisters 8ouncil on 8limate 8hange, which launched the Plan and

which was supposed to monitor its progress, has not met in the last two and a half years

;AP88 is only one part of 0ndias climate strategy. &he #!th $ive %ear &lan, which has

!ust been approved by the 8abinet, will play a "ey role in moving the country into a

sustainable development and lowAcarbon growth pathway.

'hile the 4urban platform clung on to the principles of e1uity as enshrined under the

:;888, the :.(. made it clear that it was not going to accept it. &he climate tal"s have

delivered less and less since 9ali where the twoAtrac" approach was mainly geared to

bringing on board the :.(, which is not part of the Kyoto Protocol. inances, adaptation,

mitigation and technology transfer were the "ey issues under the 9ali %oadmap. 0ndia, part

of the 2A.. group, plus 8hina had to ob!ect vociferously to the removal of the "ey pillars of

the tal"s from the 3ongAterm 8ooperative Action plan. the notion of e1uity was rooted in

historical responsibility.

;eed to ensure that the average global temperature at the end of this century did not e@ceed

that of the preAindustrial period by more than two degrees 8elsius.

At the heart of these negotiations is nothing less than the most challenging energy

transformation the world has ever seen. Past energy transitions have ta"en a long time to

unfold. irewood was man"inds first energy source and was not displaced by coal until the

5Eth century. 'ith an increasing pace of technological advance, it too" one century for oil to

replace coal as the primary global energy source. 8limate change is not the only motivation to

move toward more renewables and enhanced energy efficiency, but it has in!ected

une1uivocal urgency into an otherwise normal evolution.

&here were three contentious issues holding up a successful outcome at 8openhagenG )i* a

global goal for reduction of emissions by -7/7> )ii* measurement, reporting and verification

)#%+* of each countrys actions> and )iii* the need for a legallyAbinding global treaty.

the acceptance of a global goal could foreclose development options for developing countries.

a 1uantitative target would not be in the interests of developing countries.

the issue of international transparency of domestic commitments was paramount

Вам также может понравиться

- ECO 11 COP 17 English VersionДокумент2 страницыECO 11 COP 17 English VersionadoptnegotiatorОценок пока нет

- ECO 11 COP 17 English VersionДокумент1 страницаECO 11 COP 17 English VersionadoptnegotiatorОценок пока нет

- Article 6 of the Paris Agreement: Piloting for Enhanced ReadinessОт EverandArticle 6 of the Paris Agreement: Piloting for Enhanced ReadinessОценок пока нет

- National Strategies for Carbon Markets under the Paris Agreement: Making Informed Policy ChoicesОт EverandNational Strategies for Carbon Markets under the Paris Agreement: Making Informed Policy ChoicesОценок пока нет

- Agriculture and Climate Change: Challenges and Opportunities at the Global and Local Level - Collaboration on Climate-Smart AgricultureОт EverandAgriculture and Climate Change: Challenges and Opportunities at the Global and Local Level - Collaboration on Climate-Smart AgricultureОценок пока нет

- Infinite Solutions - COP26 Brief SummaryДокумент9 страницInfinite Solutions - COP26 Brief SummaryDedy MahardikaОценок пока нет

- The Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure (VGGT) - Popular Version for Communal Land AdministrationОт EverandThe Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure (VGGT) - Popular Version for Communal Land AdministrationОценок пока нет

- Eco Nov28Документ2 страницыEco Nov28adoptnegotiatorОценок пока нет

- Quad Cooperation in Climate Change and Launch of The Quad Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation Package (Q-CHAMP)Документ10 страницQuad Cooperation in Climate Change and Launch of The Quad Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation Package (Q-CHAMP)ramlakhan tewatiaОценок пока нет

- Eco-1!12!2012 Colour Linear 1Документ1 страницаEco-1!12!2012 Colour Linear 1kabakian_vahaknОценок пока нет

- ECO - June 13 - FinalДокумент2 страницыECO - June 13 - FinaladoptnegotiatorОценок пока нет

- ECO 10 COP 17 English VersionДокумент4 страницыECO 10 COP 17 English VersionadoptnegotiatorОценок пока нет

- From Kyoto to Paris—Transitioning the Clean Development MechanismОт EverandFrom Kyoto to Paris—Transitioning the Clean Development MechanismОценок пока нет

- TWN Update10Документ5 страницTWN Update10adoptnegotiatorОценок пока нет

- ECO-06 06 2013 ColourДокумент2 страницыECO-06 06 2013 ColouradoptnegotiatorОценок пока нет

- The Korea Emissions Trading Scheme: Challenges and Emerging OpportunitiesОт EverandThe Korea Emissions Trading Scheme: Challenges and Emerging OpportunitiesОценок пока нет

- The Paris AgreementДокумент12 страницThe Paris AgreementMukund KakkarОценок пока нет

- Accelerating hydrogen deployment in the G7: Recommendations for the Hydrogen Action PactОт EverandAccelerating hydrogen deployment in the G7: Recommendations for the Hydrogen Action PactОценок пока нет

- Taking Stock: A Global Assessment of Net Zero TargetsДокумент30 страницTaking Stock: A Global Assessment of Net Zero TargetsComunicarSe-ArchivoОценок пока нет

- NDCs and renewable energy targets in 2021: Are we on the right path to a climate safe future?От EverandNDCs and renewable energy targets in 2021: Are we on the right path to a climate safe future?Оценок пока нет

- Final Esuswatch INFORSE East Africa E Bulletin December 2023Документ3 страницыFinal Esuswatch INFORSE East Africa E Bulletin December 2023Kimbowa RichardОценок пока нет

- NVH ThesisДокумент4 страницыNVH Thesisafkndyipf100% (2)

- ECO #6 DurbanДокумент2 страницыECO #6 DurbanadoptnegotiatorОценок пока нет

- ECO-10 06 2013 ColourДокумент2 страницыECO-10 06 2013 ColouradoptnegotiatorОценок пока нет

- ECO - Bonn Climate Negotiations - May 25 2012Документ4 страницыECO - Bonn Climate Negotiations - May 25 2012kylegraceyОценок пока нет

- ECO 11 Bonn 2011 English VersionДокумент4 страницыECO 11 Bonn 2011 English VersionEllie HopkinsОценок пока нет

- Hidden Gold SeriesДокумент62 страницыHidden Gold SeriespuОценок пока нет

- ECO-03 05 2013 ColourДокумент2 страницыECO-03 05 2013 ColouradoptnegotiatorОценок пока нет

- Future Carbon Fund: Delivering Co-Benefits for Sustainable DevelopmentОт EverandFuture Carbon Fund: Delivering Co-Benefits for Sustainable DevelopmentОценок пока нет

- Virtual Stakeholder Roundtable On Adaptation and Resilience' For COP26 Charter of ActionsДокумент2 страницыVirtual Stakeholder Roundtable On Adaptation and Resilience' For COP26 Charter of Actionsleela krishnaОценок пока нет

- ECO - Bonn Climate Negotiations - May 14 2012Документ2 страницыECO - Bonn Climate Negotiations - May 14 2012kylegraceyОценок пока нет

- Rio Declaration On Environment and DevelopmentДокумент15 страницRio Declaration On Environment and DevelopmentEllaine Jane FajardoОценок пока нет

- Brazil Position PaperДокумент1 страницаBrazil Position PaperFarida OfficewalaОценок пока нет

- Media Release - IMO-MEPC72 - Moment of TruthДокумент2 страницыMedia Release - IMO-MEPC72 - Moment of TruthimoclimateОценок пока нет

- Land Degradation Neutrality in Small Island Developing States: Technical ReportОт EverandLand Degradation Neutrality in Small Island Developing States: Technical ReportОценок пока нет

- ECO - Bangkok Climate Negotiations - September 3 2012Документ2 страницыECO - Bangkok Climate Negotiations - September 3 2012kylegraceyОценок пока нет

- Adaptation Fund: Progressive But Poor!: Closing The Gap On Aviation and ShippingДокумент2 страницыAdaptation Fund: Progressive But Poor!: Closing The Gap On Aviation and ShippingadoptnegotiatorОценок пока нет

- Restoration in Action against Desertification: A Manual for Large-Scale Restoration to Support Rural Communities’ Resilience in the Great Green Wall ProgrammeОт EverandRestoration in Action against Desertification: A Manual for Large-Scale Restoration to Support Rural Communities’ Resilience in the Great Green Wall ProgrammeОценок пока нет

- The Paris Climate AgreementДокумент7 страницThe Paris Climate AgreementCenter for American ProgressОценок пока нет

- 2021 CVF LAC Communique - 24june - Final - Clean - EN 2Документ5 страниц2021 CVF LAC Communique - 24june - Final - Clean - EN 2redОценок пока нет

- Low Carbon Development StrategyДокумент128 страницLow Carbon Development StrategyAndre Valour GopaulОценок пока нет

- ECO 8 COP 17 English VersionДокумент2 страницыECO 8 COP 17 English VersionadoptnegotiatorОценок пока нет

- ECO #1 - SB-38 - 3rd June, 2013Документ2 страницыECO #1 - SB-38 - 3rd June, 2013adoptnegotiatorОценок пока нет

- Carbon Offsetting in International Aviation in Asia and the Pacific: Challenges and OpportunitiesОт EverandCarbon Offsetting in International Aviation in Asia and the Pacific: Challenges and OpportunitiesОценок пока нет

- Accelerating Climate and Disaster Resilience and Low-Carbon Development through the COVID-19 Recovery: Technical NoteОт EverandAccelerating Climate and Disaster Resilience and Low-Carbon Development through the COVID-19 Recovery: Technical NoteОценок пока нет

- Africa Climate Summit Concept NoteДокумент5 страницAfrica Climate Summit Concept NoteatipoapОценок пока нет

- 2010 12 15JairamRameshДокумент8 страниц2010 12 15JairamRameshOutlookMagazineОценок пока нет

- ECO - June 10 - FinalДокумент2 страницыECO - June 10 - FinaladoptnegotiatorОценок пока нет

- Cop ChinaДокумент2 страницыCop Chinaapi-354193053Оценок пока нет

- Climate Finance Toolkit for Europe and Central AsiaОт EverandClimate Finance Toolkit for Europe and Central AsiaОценок пока нет

- Geopolitics of the Energy Transformation: The Hydrogen FactorОт EverandGeopolitics of the Energy Transformation: The Hydrogen FactorОценок пока нет

- ECO #2 - SB-38 - 4th June, 2013Документ2 страницыECO #2 - SB-38 - 4th June, 2013adoptnegotiatorОценок пока нет

- Enb SB38 3Документ4 страницыEnb SB38 3adoptnegotiatorОценок пока нет

- ECO - Bangkok Climate Negotiations - August 31 2012Документ2 страницыECO - Bangkok Climate Negotiations - August 31 2012kylegraceyОценок пока нет

- Earth Negotiations Bulletin - 4 December, 2012Документ2 страницыEarth Negotiations Bulletin - 4 December, 2012adoptnegotiatorОценок пока нет

- Post Copenhagen Summit EditedДокумент39 страницPost Copenhagen Summit EditedHosalya DeviОценок пока нет

- Insurance (UHI) - UHI Will Free The Current Out-Of-Pocket Spending and Channel Funds TowardДокумент3 страницыInsurance (UHI) - UHI Will Free The Current Out-Of-Pocket Spending and Channel Funds TowardstrshirdiОценок пока нет

- IRCTC LTD, Booked Ticket PrintingДокумент2 страницыIRCTC LTD, Booked Ticket PrintingstrshirdiОценок пока нет

- Mobile Seva Initiative: The Project Mainly Develops and Provides Mobile Apps For Government and Citizen UseДокумент1 страницаMobile Seva Initiative: The Project Mainly Develops and Provides Mobile Apps For Government and Citizen UsestrshirdiОценок пока нет

- Ethics - AspireiasДокумент31 страницаEthics - AspireiasstrshirdiОценок пока нет

- Ramavijaya BookДокумент152 страницыRamavijaya BookVaibhavi NoticewalaОценок пока нет

- KurukshetraДокумент48 страницKurukshetraPernita PhuloriaОценок пока нет

- Rural DemographyДокумент67 страницRural DemographystrshirdiОценок пока нет

- Administrative TheoryДокумент363 страницыAdministrative TheoryAbhijit Jadhav100% (7)

- KSRTC Bus Timing: From Cochin AirportДокумент4 страницыKSRTC Bus Timing: From Cochin AirportChris JerichoОценок пока нет

- Section25 Companies PDFДокумент55 страницSection25 Companies PDFdreampedlar_45876997Оценок пока нет

- Dalit Women Talk DifferentlyДокумент4 страницыDalit Women Talk DifferentlysanjayjnuОценок пока нет

- Kerala 4 Days 3 Nights-1Документ2 страницыKerala 4 Days 3 Nights-1abinashrock619Оценок пока нет

- Syam ResumeДокумент2 страницыSyam ResumeSyam UnnikrishnanОценок пока нет

- Hrishi FinalДокумент51 страницаHrishi FinalHrishikesh MohanОценок пока нет

- Caravan Waste ArticleДокумент28 страницCaravan Waste ArticleUpneet SinghОценок пока нет

- Kerala DDДокумент12 страницKerala DDSenthamil Selvi SeenuОценок пока нет

- Institute of Land and Disaster Management: ILDM/3160/2022-A3Документ6 страницInstitute of Land and Disaster Management: ILDM/3160/2022-A31987abc123Оценок пока нет

- Plantation Companies PDFДокумент179 страницPlantation Companies PDFImage TubeОценок пока нет

- A Blueprint For Conserving The Historic Canal Precinct of Alappuzha TownДокумент34 страницыA Blueprint For Conserving The Historic Canal Precinct of Alappuzha TownThomas IsaacОценок пока нет

- Final IICFReportДокумент94 страницыFinal IICFReportSujith AshokОценок пока нет

- Annual Passenger Earnings NewДокумент6 страницAnnual Passenger Earnings NewprajscribОценок пока нет

- 3B Defaulter October 2019 PDFДокумент1 340 страниц3B Defaulter October 2019 PDFJamesОценок пока нет

- Go Ms No 91-10-hfwdДокумент14 страницGo Ms No 91-10-hfwddoctor82Оценок пока нет

- Circular No 87-2016-Fin Dated 18-11-2016Документ4 страницыCircular No 87-2016-Fin Dated 18-11-2016SUNIL50% (2)

- 2 Planning PF Coastal Protection Measures Along Kerala CoastДокумент209 страниц2 Planning PF Coastal Protection Measures Along Kerala CoastVarsha RanganathaОценок пока нет

- Case StudyДокумент4 страницыCase StudykarunaОценок пока нет

- 4 Alappuzha FinalДокумент295 страниц4 Alappuzha FinalJamesОценок пока нет

- MediAssist Kerala Hospital ListДокумент5 страницMediAssist Kerala Hospital Listtijuantony0% (3)

- 3213 Part A KollamДокумент230 страниц3213 Part A KollamAKSHEY SREEKUMARОценок пока нет

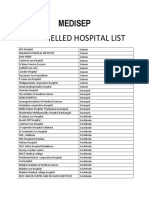

- Empanelled Hospital ListДокумент7 страницEmpanelled Hospital ListExpress WebОценок пока нет

- Traditional Industries KeralaДокумент5 страницTraditional Industries KeralaBulle ShahОценок пока нет

- IIA KeralaДокумент34 страницыIIA KeralamanishaОценок пока нет

- MB Mathrubhumi Calendar 2012Документ6 страницMB Mathrubhumi Calendar 2012He Llo E RrorОценок пока нет

- Exporters NewДокумент708 страницExporters Newvaibhav.anОценок пока нет

- HAATДокумент6 страницHAATRevathy NandaОценок пока нет

- Fishermen CommunityДокумент15 страницFishermen CommunityRájDèép Trìpâţhí100% (1)

- IFSCДокумент250 страницIFSCpapuali_100Оценок пока нет

- Ksfe List of All BranchesДокумент20 страницKsfe List of All BranchesazadОценок пока нет