Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Forest 2009 Political Representation

Загружено:

Bo0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

16 просмотров6 страницPolitical Representation

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документPolitical Representation

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

16 просмотров6 страницForest 2009 Political Representation

Загружено:

BoPolitical Representation

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 6

Political Representation

B. Forest, McGill University, Montre al, QC, Canada

& 2009 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Glossary

Descriptive Representation A principle of political

representation in which the social and/or demographic

composition of an elected body is similar to that of the

population or voting constituency.

Gerrymandering The manipulation of electoral district

boundaries intended to affect the outcome of elections.

Independence Theory of Representation A theory

of political representation in which the representative is

free to act independent from, and even contrary to, the

preferences of her/his constituents.

Mandate Theory of Representation A theory of

political representation in which the representative if

bound to act strictly in accordance with the preferences

of her/his constituents.

Proportional Representation An electoral system in

which voters cast ballots for parties rather than

candidates, and representatives are selected from lists

generated by parties in accordance with the proportion

of votes received by each party.

Territorial Representation An electoral system in

which candidates are elected from geographically

dened constituencies.

Substantive Representation A principle of political

representation where the interests of social,

demographic, and/or political groups are represented in

an elected body.

VoteSeat Ratio The ratio between the proportion of

votes a party wins and the proportion of seats the party

receives.

The Meanings of Political Representation

Nearly 40 years ago, political theorist Hannah Pitkin

argued that only a constellation of meanings could ad-

equately describe representation, and political represen-

tation in particular. The concept is so complex because

representation is an apparent absurdity: to make present

something that is not literally present. This would be

difcult enough if the something in question was a

simple object in the world, but an act of political rep-

resentation more typically calls the something into being.

In other words, an election or the formation of a legis-

lature constitutes the object being represented, for

example, the people, the will of the people, the nation,

the national interest, etc. At the same time, political

representation (at least in functioning democracies) must

also be a practical activity providing the means of gov-

ernance. The relationships among representation and

geography involve both the constitutive and the practical

dimensions of representation.

All democratic political representation relies on a

kind of political ction, the existence of the people as a

sovereign-holding, but abstract entity. That is, the people

hold power, but it is never possible to actually identify a

particular set of the population as the people. Indeed,

every less-than-unanimous vote reveals the ctitious

nature of the people because any resulting representative

or policy will have the support of (at best) a majority of

voters. Democratic political representation presents a

particular dilemma because the people are simul-

taneously rulers and subjects. As rulers, they are free to

act according to their political will, but as subjects, they

are bound by their own decisions. Political represen-

tation, and its practice in electoral systems, resolves this

dilemma by delegating power to representatives who

carry out the activities of governance. These represen-

tatives are typically restrained by constitutional provisions

and previously established laws as well as by future

elections.

The creative or constitutive nature of political rep-

resentation means that all systems of political represen-

tation have both actual and imaginary geographies. That

is, geographical studies of political representation involve

issues such as voting patterns and the division of state

powers, but also issues such as the right to vote, a

question that fundamentally denes the nature of the

state or nation.

Issues of political representation have attracted in-

creasing interest in political and electoral geography in

the last 20 years. The roots of this renewed interest lie in

historical, technical, and disciplinary developments. First,

the fall of communism in Central and Eastern Europe

(198990), the breakup of the Soviet Union (1991), and

the end of apartheid in South Africa (199194) led to a

renewed wave of democratization that often required

careful negotiation over both the institutional forms of

electoral systems and the nature of the political com-

munities to be represented. Second, the increased power

and sophistication of geographic information systems

(GISs) have brought new analytic power to the practice

of political districting and the analysis of voting patterns.

Finally, electoral geography is also moving beyond the

analysis of spatial patterns of voting, instead focusing

more on place-specic or neighborhood effects on vot-

ing preferences. These developments mean that political

254

geography in general, and electoral geography in

particular, has had to reexamine its assumptions about

political representation and related concepts.

The MandateIndependence Debate

Debate over the role of the representative, the so-called

mandateindependence debate, is one of the central

issues in political representation. Under the mandate

theory, a representative must always act in accordance

with the will of her/his constituents, and indeed, ceases

to represent them if s/he goes against their wishes.

Strictly speaking, the mandate theory holds that a rep-

resentative is simply a delegate, acting as a conduit to

convey the actions and interests of voters to an assembly.

In contrast, the independence theory characterizes the

representative as free to act according to her/his own

judgment and will, recognizing representatives as having

unique skills and expertise unavailable to a typical

constituent. This perspective would recognize a person

as a representative even if s/he acts contrary to the

expressed wishes of the constituency. The common

meaning of democratic political representation lies

somewhere between these two extremes, and relies on a

reciprocal relationship between the represented and the

representative.

Pitkin in particular argues that a proper understand-

ing of political representation requires elements of both

theories. The represented must be seen as capable of

understanding and expressing their own interests, rather

than simply being the subjects of caretaking (like children

or the mentally inrm). There should not typically

be conict between the wishes of constituents and the

actions of the representative, but such divergence must

be possible. When differences arise, the representative

must be able to explain and justify them. Democratic

states institutionalize this reciprocal relationship through

periodic elections, where voters can (in principle) replace

inadequate representatives.

Descriptive and Substantive Representation

Another major debate involves the relationship between

the identity of the representative and the composition

of her/his constituency. Political theorists typically

characterize this as a conict between descriptive and

substantive representation, sometimes described as the

politics of presence versus the politics of interests or

ideas. (Such discussions occur most often in the context

of gender, racial, ethnic, or religious minorities, but

are not necessarily limited to the role of such groups.)

Descriptive representation or the politics of presence

requires the physical presence of women, ethnic minor-

ities, etc. in a representative assembly. In a sense, a body

is representative when groups are present in the assembly

in the same proportion as in the population. Some argue

that descriptive representation has a value in and of itself,

and/or that it helps confer legitimacy to an elected

government, particularly in societies with signicant in-

equality and stratication. More sophisticated defenses

of descriptive representation suggest that the presence of

women and minorities actually changes the quality and

nature of deliberation in legislative bodies. A number of

representative democracies, such as India, have insti-

tutionalized the politics of presence by instituting quotas

for women and minority groups in legislative bodies. The

US also imposed gender quotas for elections in Iraq,

although it eschews them at home.

In contrast, substantive representation regards the

identity of the delegates as irrelevant because represen-

tatives are seen as agents protecting the interests of

constituents. While voters may consider the identity

of candidates while voting, the demographic composition

of the legislature per se is not important as long as rep-

resentatives are chosen in a way that allows the effective

expression of the interests of voters. A male, for instance,

would be seen as representative of females if he con-

sistently supported womens interests. The concept of

such objectively dened interests, however, can lead to

an apparent absurdity. If interests exist objectively, sub-

stantive representation suggests that a constituency need

not have a role in electing their representative, as with

the caretaker of a child or incapacitated adult. Con-

sequently, in its extreme form, substantive representation

poses problems that are similar to those found in the

independence theory of representation. This issue was

one of the major disputes during the American Revo-

lution, where the colonists objected to their virtual

representation in Parliament by representatives for

whom they had not voted.

As a practical matter, democratic representation

seldom involves either descriptive or substantive repre-

sentation exclusively. Even among voters who might

reject the idea of legislative or party list quotas, the

gender or ethnic identity of candidates can be a concern if

they feel that a member of their own group is better able

to understand and represent their interests. Much like the

mandateindependence debate, the extreme version of

each form of representation violates the principle that

within limits both representatives and constituents must

be able to act freely and to exercise judgment.

Critics of Democratic Representation

Marxist critics in particular argue that such theoretical

debates are irrelevant because democratic represen-

tation is impossible under a capitalist system. The

interests of capital too easily determine elections, and

debates between parties and candidates simply serve to

disguise how the state acts in the interests of capital. The

Political Representation 255

idea of candidates and parties competing with each other

is simply a political version of free-market economic

ideology. For these critics, structural forces rather than

individual merit or effort determine the winners and

losers in each realm. Insofar as political debate takes

place through the media, major corporations can easily

control the content and structure of political discussion

and identify only favorable candidates as legitimate and

serious. Similarly, the funding required for political

campaigns means that wealthy individuals and organ-

izations exercise a disproportionate impact on elections.

Moreover, elections themselves may be largely irrelevant

because those with the most inuence over represen-

tatives lobbyists, institutions, corporations, and so forth

are not affected by elections. The interests of capital

are represented regardless of the form of democratic

representation.

Electoral Systems and Political

Representation

Disputes over political representation generally take

place in conicts over electoral systems, rather than in

abstract policy debates. An electoral system is the

mechanism through which votes are translated (or not)

into political power. Within liberal democracies an

enormous variety of electoral systems exist in pure or

mixed forms, although most are variations of either

proportional representation (PR) or territorial-plurality

representation. Each system translates votes into power

in slightly different ways. Each offers particular tradeoffs

in the relationship between representatives and con-

stituents, and in the stability and responsiveness of

the political system. The choice of an electoral system

reects the institutionalized political values of a society

or at least the values of those in a position to choose the

system.

Proportional Representation

PR is the most common electoral system in the world.

It attempts to translate the proportion of votes for a

particular party into the same proportion of seats in

the elected assembly. Typically, parties establish a list of

candidates who win seats in proportion to the number of

votes the party receives. For example, in a parliament

with 200 open seats, a party receiving 50% of the vote

would place the rst 100 candidates on its list in the

assembly. All proportional systems, however, have limi-

tations. The total number of contested seats determines

the minimum percentage of votes required to elect a

representative. In a 200-seat parliament, a party would

need at least 0.5% (1/200) of the vote to place one

candidate. In practice, however, most jurisdictions using

PR establish a minimum threshold for electing candidates

(typically around 5%) regardless of the theoretical

minimum. Any party receiving less than the threshold

cannot place candidates in the assembly, and the re-

maining seats are allocated to the other parties. Table 1

shows the results with ve parties contesting a 200-

member assembly with a 5% minimum threshold for

election.

In this example the remaining seats are allocated

proportionally, rounding up to the nearest whole number,

but other methods can be used as well. The example

illustrates that proportional systems may not produce

proportionality; the top three vote-getting parties receive

extra seats, and the two smallest parties, representing

8% of the voters, are completely shut out. This problem

of disproportionality is worse in elections where a large

number of small parties fail to meet the minimum

threshold, or where the minimum threshold is very high.

States typically require minimum thresholds to limit

political fragmentation by forcing small constituencies to

nd common ground in one party or another. In parlia-

mentary systems, very low thresholds can give excessive

inuence to small parties who hold the balance of power

in coalition governments.

Territorial-Plurality Representation

The other common electoral system is territorial-

plurality representation. In the simplest version of such a

system, two or more candidates compete for a single seat

from a specic territorial unit (districts, ridings, boroughs,

etc.). In such single-member, rst-past-the-post systems,

the candidate with a plurality (or majority) of votes

wins the election. The major advantages of such systems

are (in principle) greater accountability and closer

Table 1 Allocating seats in a proportional system with 5% minimum threshold in a 200-member assembly

Party Percentage of the vote Initial seats Remaining seats Total seats Percentage of seats

(% Vote X 200) (% Vote X (200184))

A 42 84 7 91 45.5

B 30 60 5 65 32.5

C 20 40 4 44 22

D 4

E 4

Total 100 184 16 200 100

256 Political Representation

ties between a representative and her/his constituents

because representation is tied to a specic geographic

region and to a specic territorial constituency. All

territorial-plurality systems, however, suffer from the

so-called voteseat problem: the proportion of votes

gained by a party as a whole may not correspond closely

to the proportion of seats they receive in the legislature.

Table 2 illustrates how territorial representation can lead

to such disproportionality in a ve-member assembly

representing ve districts with equal numbers of voters.

In this example, candidates from Party A win close

elections in four of the ve districts but the party loses

the fth district badly. The four narrow margins mean,

however, that Party A wins 80% of the seats in the

assembly with just over 40% of the total vote. (Under PR,

Party A would win just two of the ve seats or 40%.)

Departures from proportionality can be even more severe

if three or more parties contest each district and winning

candidates only achieve pluralities rather than majorities.

Perhaps the best-known recent example of the voteseat

problem was the 2000 US presidential election, in which

George W. Bush received fewer votes than Vice-

President Al Gore, but won the election with narrow

victories in several states. Although the voteseat prob-

lem is endemic to all territorial systems of representation,

it is of particular concern when it leads to the exclusion

of political (gender, ethnic, or religious) minorities.

Territorial systems are also highly vulnerable to ger-

rymandering, a technique that inuences the voteseat

ratio by manipulating the boundaries of electoral dis-

tricts, boroughs, or ridings.

Variations of the single-member, rst-past-the-post

system can either ameliorate or exaggerate the voteseat

mismatch. The voting system in multimember or at-large

districts (where candidates run for several seats simul-

taneously) can either completely exclude minority par-

ties and candidates, or can provide a mechanism for

proportionality. In the former case, election rules might

require candidates to run for particular seats, and require

voters to cast one and only one vote for each seat.

A cohesive political plurality could then elect all repre-

sentatives. Alternatively, candidates might all run against

each other simultaneously with the top vote getters

winning election. Such an arrangement prevents the ex-

clusion of a political minority, but allows the election of

candidates who have a relatively narrow base of support.

If the top candidate attracts 70% of the vote, for example,

the remaining representatives would be elected with less

than 30% support among the electorate. Nor do such

systems guarantee proportionality since (as in the above

example) a single candidate might win the lions share of

the vote.

Numerous electoral mechanisms have been proposed

and employed to overcome the seatvote mismatch and

to address the problem of minority exclusion. The single

transferable vote (STV) (called instant run-off voting

or IRV when used to elect candidates to a single seat)

identies the candidates with the broadest support by

having voters rank them in order of preference. Ballots

that would otherwise be wasted (either because the rst-

choice candidate received more votes than needed for

election, or too few to be competitive) are transferred

to the voters second- (third-, etc.) ranked candidate until

all seats are lled. STVattempts to ensure a closer match

in proportionality between votes and seats while still

retaining a territorially based system of representation.

Mixed Electoral Systems

States and other jurisdictions use a wide array of pro-

portional and territorial electoral systems, and scholars

have proposed an even greater variety to address the

practical and theoretical shortcomings of the existing

ones. PR and territorial-plurality systems are not

necessarily mutually exclusive, however, and many jur-

isdictions use some combination of them. Some seats in a

legislature, for example, might be elected from territorial

units while the remaining seats are assigned by pro-

portion of the total vote. Proportional systems may also

be used within a set of districts, where parties designate

separate lists for each territorial unit. The effect on

proportionality in these cases depends on the particular

design of the electoral system and on the distribution

of votes in any given election. Mixed systems often

Table 2 Territorial-plurality representation in a ve-member assembly

District % Votes for

candidates from

party A

% Votes for

candidates from

party B

Winning

candidate

1 51 49 A

2 52 48 A

3 51 49 A

4 52 48 A

5 10 90 B

Total votes 43.2 56.8

Total seats 80 20

(4 seats) (1 seat)

Political Representation 257

reect practical compromises among political factions

who would benet disproportionally from either PR or

territorial representation. As such, they embody mixed

principles and concepts of representation.

Principles of Representation in Electoral

Systems

Arguably, PR can promote both descriptive and

substantive representation more easily than territorial

representation because it is simpler to regulate the

composition of party lists than the composition of terri-

torial electorates. It is easier, for example, to require

that women or minorities constitute some minimum

percentage of the candidates on party lists, than to create

electoral districts where the same percentage of women

or minorities are likely to be elected. PR used with such

regulated party lists can thus easily guarantee descriptive

representation in an elected body. The profusion of

parties in a PR system may also increase the chances

that a particular constituency or interest group will have

representatives in the assembly.

PR (especially without regulated party lists) suggests a

bias toward the independent model and substantive

representation because representatives generally have

weaker ties to a particular constituency even one that

is concentrated geographically. Representatives are not

personally tied to a set of voters because voters cast

ballots for a party rather than individuals. Represen-

tatives thus embody the interests and positions of the

party, rather than a specic constituency per se, and

are consequently freer to act according to their own

judgment (within the limits of party discipline) and are

(arguably) less accountable to voters.

Although territorial representation is typically less

effective in creating proportionality and descriptive

representation, district systems ensure a strong tie be-

tween representatives and their constituencies, and in

principle increase accountability. Such a system en-

courages a mandate model because voters can remove

specic incumbents in favor of candidates who will more

accurately represent their wishes. More generally, terri-

torial systems allow for a distinct concept of the object of

representation: the geographic community. Rather than

representing the agglomerated will of individual voters

(as in PR), a representative comes from and embodies a

particular, identiable community that is or is imagined

to be more than the sum of its individual members.

Responsiveness and Stability in Electoral

Systems

Electoral systems must also balance responsiveness and

stability. These refer to the relationship between a

change in voting patterns and the consequent change in

the elected assembly. PR systems are (in theory) perfectly

responsive; a 5% increase (or decrease) in the votes for a

party will translate into a 5% increase (or decrease) in

the number of seats held by that party. In practice,

changes in vote totals may not translate perfectly into

changes in seat totals because of threshold requirements

and limited assembly size.

The balance between stability and responsiveness is

more complex in territorial representation because the

voteseat ratio of a particular set of electoral districts

can produce outcomes that are either too stable or too

responsive. In the former case, even large changes in the

overall vote total do not change the composition of

the elected assembly, whereas in the latter case, small

changes in the vote produce huge swings in the legis-

lature. Overly stable systems result when parties have

either large majorities or small minorities in districts.

Even relatively large losses or gains by one party or

another in total votes are not sufcient to change the

majorities or minorities in many districts, so the com-

position of the assembly remains unchanged. In contrast,

a set of districts with very narrow margins may be overly

responsive because a tiny shift in the electorate may

cause one party to lose every seat. A particular set of

electoral districts may also be asymmetrically responsive:

a large loss of votes by one party may not produce

any change in the assembly, but a small gain in votes

may result in signicant gains.

Stability and responsiveness raise nal dilemma of

territorial representation. The principle of accountability

holds that voters should be able to remove an incumbent

from ofce, and elected ofcials are presumably more

responsive to their constituents if they are in danger of

losing the next election. At the same time, legislatures

benet from some degree of political continuity and

stability. Thus a situation that is desirable in an indi-

vidual district accountability ensured by narrow elec-

tion margins may produce excessive responsiveness

when applied in every district.

Political Representation and Political

Communities

Concepts and principles of political representation are

fundamental not only to the structure of electoral sys-

tems, but also to the relationships among the franchise,

the polity, and citizenship. In nation-states, the right to

vote is one criterion of membership in the nation, but

in all states, this right is a measure of full citizenship. Full

citizenship, including the franchise, confers membership

in the people. A full citizen therefore carries both the

right of sovereign power and political interests that

require representation. In short, only full citizens are full

participants in the political life of a state. In this way, acts

258 Political Representation

of political representation create political communities

rather than simply reecting the will of preexisting

ones. Consequently, analyses of political representation

ultimately involve issues of citizenship, exclusion, and

power. While systems of territorial representation present

clear geographic questions, all systems of political rep-

resentation even pure PR raise signicant issues

for political geographers.

See also: Citizenship; Democracy; Electoral Cartography;

Electoral Districts; Electoral Geography; Gerrymandering;

Governance; Identity Politics; Private/Public Divide.

Further Reading

Forest, B. (2001). Mapping democracy: Racial identity and the

quandary of political representation. Annals of the Association of

American Geographers 91, 143--166.

Johnston, R. (2002). Manipulating maps and winning elections:

Measuring the impact of malapportionment and gerrymandering.

Political Geography 21, 1--31.

Johnston, R., Pattie, C., Dorling, D. and Rossiter, D. (2001). From votes

to seats: The operation of the UK electoral system since 1945.

Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Keyssar, A. (2000). The right to vote: The contested history of

democracy in the United States. New York: Basic Books.

Lijphart, A. (1999). Patterns of democracy: Government forms and

performance in thirty-six countries. New Haven: Yale University

Press.

Lublin, D. (1997). The paradox of representation: Racial

gerrymandering and minority interests in Congress. Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press.

Marston, S. A. (1990). Who are the people?: Gender, citizenship, and

the making of the American nation. Environment and Planning D:

Society and Space 8, 449--458.

Monmonier, M. S. (2001). Bushmanders and bullwinkles: How

politicians manipulate electronic maps and census data to win

elections. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Morgan, E. S. (1988). Inventing the people: The rise of popular

sovereignty in England and America. New York: W. W. Norton and

Company.

Phillips, A. (1995). The politics of presence. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Pitkin, H. (1967). The concept of representation. Berkeley: University of

California Press.

Relevant Websites

http://www.fairvote.org/

A site with many election-related resources, sponsored by the

Center for Voting and Democracy.

http://www.electoralgeography.com/new/en/

A site with many worldwide election results and electroal maps,

especially of recent elections.

http://www.redistrictinggame.org/

An interactive redistricting site from the Annenberg Center at the

University of Southern California.

Political Representation 259

Вам также может понравиться

- J S Mill, Representative Govt.Документ7 страницJ S Mill, Representative Govt.Ujum Moa100% (2)

- Essay Smaele Access To Information As A Crucial Element in The Balance of Power Between Media & PoliticsДокумент16 страницEssay Smaele Access To Information As A Crucial Element in The Balance of Power Between Media & PoliticsBoОценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (894)

- How To Keep Score For A Softball GameДокумент19 страницHow To Keep Score For A Softball GameBo100% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- John Stuart Mill's Theory of Bureaucracy Within Representative Government: Balancing Competence and ParticipationДокумент11 страницJohn Stuart Mill's Theory of Bureaucracy Within Representative Government: Balancing Competence and ParticipationBoОценок пока нет

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- Expert Paper Perl Terrorism, The Media, and The GovernmentДокумент14 страницExpert Paper Perl Terrorism, The Media, and The GovernmentBoОценок пока нет

- Info Pack 2014Документ27 страницInfo Pack 2014BoОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Derthick, M. (2007) - Where Federalism Didn't FailДокумент12 страницDerthick, M. (2007) - Where Federalism Didn't FailBoОценок пока нет

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Libertarian Philosophy of John Stuart MillДокумент17 страницThe Libertarian Philosophy of John Stuart MillPetar MitrovicОценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Muller, E.R. (2010) - Policing & Accountability in The NLДокумент11 страницMuller, E.R. (2010) - Policing & Accountability in The NLBoОценок пока нет

- Sullivan Review Godfather DoctrineДокумент3 страницыSullivan Review Godfather DoctrineBoОценок пока нет

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Derthick, M. (2007) - Where Federalism Didn't FailДокумент12 страницDerthick, M. (2007) - Where Federalism Didn't FailBoОценок пока нет

- Expert Paper Bakker & de Graaf Lone WolvesДокумент8 страницExpert Paper Bakker & de Graaf Lone WolvesBoОценок пока нет

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Turner, B. (1976) - The Organizational and Interorganizational Development of Disasters, Administrative Science Quarterly, 21 378-397Документ21 страницаTurner, B. (1976) - The Organizational and Interorganizational Development of Disasters, Administrative Science Quarterly, 21 378-397BoОценок пока нет

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Boin, A., Kuipers, S. & Overdijk, W. (2013) - Leadership in Times of Crisis: A Framework For AssessmentДокумент13 страницBoin, A., Kuipers, S. & Overdijk, W. (2013) - Leadership in Times of Crisis: A Framework For AssessmentBoОценок пока нет

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The More Things Change The More They Stay The SameДокумент3 страницыThe More Things Change The More They Stay The SameBoОценок пока нет

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- TN GodfatherДокумент3 страницыTN GodfatherBoОценок пока нет

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- "Patient Zero": The Absence of A Patient's View of The Early North American AIDS EpidemicДокумент35 страниц"Patient Zero": The Absence of A Patient's View of The Early North American AIDS EpidemicBo100% (1)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- v39 I2 08-Bookreview Godfather DoctrineДокумент2 страницыv39 I2 08-Bookreview Godfather DoctrineBoОценок пока нет

- Health Education Journal 1988 Articles 104Документ2 страницыHealth Education Journal 1988 Articles 104BoОценок пока нет

- Randy M. Shilts 1952-1994 Author(s) : William W. Darrow Source: The Journal of Sex Research, Vol. 31, No. 3 (1994), Pp. 248-249 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 02/09/2014 13:37Документ3 страницыRandy M. Shilts 1952-1994 Author(s) : William W. Darrow Source: The Journal of Sex Research, Vol. 31, No. 3 (1994), Pp. 248-249 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 02/09/2014 13:37BoОценок пока нет

- Engert & Spencer IR at The Movies Teaching and Learning About International Politics Through Film Chapter4Документ22 страницыEngert & Spencer IR at The Movies Teaching and Learning About International Politics Through Film Chapter4BoОценок пока нет

- Chapter 9 An Averted Threat To DemocracyДокумент20 страницChapter 9 An Averted Threat To DemocracyBoОценок пока нет

- Update '89: Alvin E. Friedman-Kien, MD, Symposium DirectorДокумент13 страницUpdate '89: Alvin E. Friedman-Kien, MD, Symposium DirectorBoОценок пока нет

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- J Hist Med Allied Sci 2014 Kazanjian 351 82Документ32 страницыJ Hist Med Allied Sci 2014 Kazanjian 351 82BoОценок пока нет

- Wraith Et Al The MucopolysaccharidosesДокумент9 страницWraith Et Al The MucopolysaccharidosesBoОценок пока нет

- Acute Airway Obstruction in Hunter Syndrome: Case ReportДокумент6 страницAcute Airway Obstruction in Hunter Syndrome: Case ReportBoОценок пока нет

- Wetenschappelijke Artikelen Over Bone Marrow Transplant HunterДокумент11 страницWetenschappelijke Artikelen Over Bone Marrow Transplant HunterBoОценок пока нет

- Stem-Cell Transplantation For Inherited Metabolic Disorders - HSCT - Inherited - Metabolic - Disorders 15082013Документ19 страницStem-Cell Transplantation For Inherited Metabolic Disorders - HSCT - Inherited - Metabolic - Disorders 15082013BoОценок пока нет

- Tolun 2012 A Novel Fluorometric Enzyme Analysis Method For Hunter Syndrome Using Dried Blood SpotsДокумент3 страницыTolun 2012 A Novel Fluorometric Enzyme Analysis Method For Hunter Syndrome Using Dried Blood SpotsBoОценок пока нет

- Sohn 2013. Phase I-II Clinical Trial of Enzym Replacement Therapy MPS IIДокумент8 страницSohn 2013. Phase I-II Clinical Trial of Enzym Replacement Therapy MPS IIBoОценок пока нет

- Electoral Politics PPT - Class 9Документ31 страницаElectoral Politics PPT - Class 9aannoosandhuОценок пока нет

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Orientation For WatchersДокумент44 страницыOrientation For WatchersNewCovenantChurchОценок пока нет

- Chapter-4 Political Science Electoral Politics: ElectionsДокумент1 страницаChapter-4 Political Science Electoral Politics: ElectionsTimo PaulОценок пока нет

- Comelec Sample Ballot 2013 PDFДокумент2 страницыComelec Sample Ballot 2013 PDFQuentinОценок пока нет

- Uber Answer SheetДокумент4 страницыUber Answer Sheetrosemarie.reas.gsbmОценок пока нет

- Election Commission of India: WWW - Eci.gov - inДокумент54 страницыElection Commission of India: WWW - Eci.gov - incaroom hyderabadОценок пока нет

- Library and Informationscience ReviewerДокумент253 страницыLibrary and Informationscience ReviewerLloyd LapeОценок пока нет

- The Constitution For Students of Swansea inДокумент20 страницThe Constitution For Students of Swansea inapi-26181490Оценок пока нет

- Q4 W1 Trends, Networks - KSA-LeaPДокумент5 страницQ4 W1 Trends, Networks - KSA-LeaPMary Jane CalandriaОценок пока нет

- MMW - M5 - Check-In Activity 4Документ3 страницыMMW - M5 - Check-In Activity 4Diana Joy MoranteОценок пока нет

- The Right of SuffrageДокумент18 страницThe Right of SuffrageJoana MarananОценок пока нет

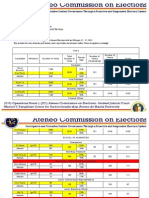

- Memo 201309 - 2013 Sanggu General Elections ResultsДокумент19 страницMemo 201309 - 2013 Sanggu General Elections ResultsAteneo COMELECОценок пока нет

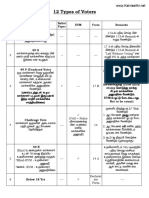

- 12 types of votersДокумент13 страниц12 types of votersAshok KumarОценок пока нет

- Interim Procedure For Conduct of Election of Officers of The PCG Officers' Club (PCGOC)Документ6 страницInterim Procedure For Conduct of Election of Officers of The PCG Officers' Club (PCGOC)mc_abelaОценок пока нет

- 6320 ScriptДокумент2 страницы6320 Scriptapi-534392985Оценок пока нет

- Chapter 4Документ43 страницыChapter 4Nasser AbdullahОценок пока нет

- Philippine Elections and Political Parties ExplainedДокумент15 страницPhilippine Elections and Political Parties ExplainedAries Jen Palaganas71% (7)

- Parliamentary Procedure Guide for City OfficialsДокумент21 страницаParliamentary Procedure Guide for City Officialsrch1203Оценок пока нет

- Michael Gallagher, Paul Mitchell-The Politics of Electoral Systems (2008)Документ689 страницMichael Gallagher, Paul Mitchell-The Politics of Electoral Systems (2008)Hari Madhavan Krishna Kumar100% (2)

- Mandatory VotingДокумент11 страницMandatory VotingBrymak BryantОценок пока нет

- Chapter 18 Lesson 2Документ14 страницChapter 18 Lesson 2api-262327064Оценок пока нет

- Other Privileged Class Deviance SДокумент21 страницаOther Privileged Class Deviance SDEBJIT SAHANI100% (1)

- Principles and Practice of ManagementДокумент19 страницPrinciples and Practice of ManagementHari Kishan25% (4)

- ENG Roberts Rules of OrderpptДокумент31 страницаENG Roberts Rules of OrderpptDahouk MasaraniОценок пока нет

- IEBC Gazettes Names of Returning Officers Ahead of August ElectionsДокумент9 страницIEBC Gazettes Names of Returning Officers Ahead of August ElectionsThe Star Kenya50% (2)

- Barangay MaysiloДокумент286 страницBarangay MaysiloAn Jannette Almodiel100% (1)

- Tanzania Electoral Commission Paper on Country's Electoral ProcessДокумент22 страницыTanzania Electoral Commission Paper on Country's Electoral ProcessRick MoxОценок пока нет

- PCATP Election Schedule 2023Документ11 страницPCATP Election Schedule 2023Connect HanguОценок пока нет

- Management Decision MakingДокумент37 страницManagement Decision MakingPaul ContrerasОценок пока нет

- Navigating Through Mathematics 1St Edition Collins Test Bank Full Chapter PDFДокумент43 страницыNavigating Through Mathematics 1St Edition Collins Test Bank Full Chapter PDFkatherinegarnerjwcrantdby100% (8)

- The Russia Hoax: The Illicit Scheme to Clear Hillary Clinton and Frame Donald TrumpОт EverandThe Russia Hoax: The Illicit Scheme to Clear Hillary Clinton and Frame Donald TrumpРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (11)

- Nine Black Robes: Inside the Supreme Court's Drive to the Right and Its Historic ConsequencesОт EverandNine Black Robes: Inside the Supreme Court's Drive to the Right and Its Historic ConsequencesОценок пока нет

- The Smear: How Shady Political Operatives and Fake News Control What You See, What You Think, and How You VoteОт EverandThe Smear: How Shady Political Operatives and Fake News Control What You See, What You Think, and How You VoteРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (16)

- The Deep State: How an Army of Bureaucrats Protected Barack Obama and Is Working to Destroy the Trump AgendaОт EverandThe Deep State: How an Army of Bureaucrats Protected Barack Obama and Is Working to Destroy the Trump AgendaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (4)

- Commander In Chief: FDR's Battle with Churchill, 1943От EverandCommander In Chief: FDR's Battle with Churchill, 1943Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (16)

- We've Got Issues: How You Can Stand Strong for America's Soul and SanityОт EverandWe've Got Issues: How You Can Stand Strong for America's Soul and SanityОценок пока нет