Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Chris McDaniel MSSC Brief in McDaniel vs. Cochran

Загружено:

Russ LatinoОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Chris McDaniel MSSC Brief in McDaniel vs. Cochran

Загружено:

Russ LatinoАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF MISSISSIPPI

2014-EC-01247-SCT

CHRIS McDANIEL APPELLANT

v.

THAD COCHRAN APPELLEE

APPEAL FROM THE CIRCUIT COURT OF JONES COUNTY, MISSISSIPPI

HONORABLE W. HOLLIS McGEHEE, SPECIALLY APPOINTED

CIRCUIT JUDGE PRESIDING

BRIEF OF APPELLANT

Mitchell H. Tyner, Sr., MSB No. 8169

TYNER LAW FIRM, P.A.

5750 I-55 North

Jackson, Mississippi 39211

Steve C. Thornton, MSB No. 9216

ATTORNEY AT LAW

P. O. Box 16465

Jackson, Mississippi 39236

ATTORNEYS FOR CHRIS McDANIEL

Submitted September 18, 2014

1

E-Filed Document Sep 18 2014 20:26:54 2014-EC-01247-SCT Pages: 49

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS

Undersigned counsel of record certifies that the following listed persons have an interest

in the outcome of this case. These representations are made in order that the justices of the

Supreme Court and/or the judges of the Court of Appeals may evaluate possible disqualification

or recusal.

1. W. Hollis McGehee, Specially Appointed Judge, Circuit Court, Jones County,

Mississippi.

2. Chris McDaniel, Appellant

3. Mitchell H. Tyner, Sr., Attorney for Appellant

4. Steve C. Thornton, Attorney for Appellant

5. Thad Cochran, Appellee

6. Phil B. Abernethey, Attorney for Appellee

7. Mark Garriga, Attorney for Appellee

8. Butler Snow Omara Stevens & Cannada, Attorneys for Appellee

9. Mississippi Republican Party

s/ Steve C. Thornton

Steve C. Thornton

ATTORNEY FOR CHRIS McDANIEL

2

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

TABLE OF CONTENTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

STATEMENT OF ISSUES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

STATEMENT OF THE CASE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

ARGUMENT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

I. Election Code 23-15-923 does not impose a specific time requirement for filing

a complaint with a political partys state executive committee to contest a

primary election for state-wide office. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

II. Other sections of the Election Code impose many deadlines but none on filing a

complaint to contest a primary election for state-wide office with a political

partys state executive committee. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

III. The absence of a deadline in Election Code 23-15-923 is evidence of intent

by the Legislature that no specific time requirement be imposed. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

IV. The Mississippi Legislature expressed a clear intent to repeal former Mississippi

election laws regulating primary elections. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

V. The Election Code made material changes in Mississippis election statutes and

specifically to the predecessors of 23-15-923. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

VI. Kellum v. Johnsons interpretation of former election statutes (now repealed) is

not binding precedent on the interpretation of the current Election Code.. . . . . . . . . 30

VII. Kellum v. Johnson was inconsistent with well-settled principles of law when it

was decided. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

VIII. If Kellum v. Johnson had any precedential value after the overhaul of the

Election Code in 1986, it would have been followed in Barbour v. Gunn. . . . . . . . . 37

IX. The Doctrine of sub silentio was misapplied by the lower court. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42

3

X. To disregard the ruling in Barbour v. Gunn would create a double standard and

void the decision in Barbour v. Gunn, ab initio. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

CONCLUSION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

4

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Mississippi Cases

Adams v. Yazoo & M.V.R. Co.,

75 Miss. 275, 22 So. 824 (1897) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

A.T.&T. v. Days Inn of Winona,

720 So.2d 178 (Miss. 1998) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

Barbour v. Gunn,

890 So. 2d 843 (Miss. 2004) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15, 37, 39, 40, 41, 43, 45, 46

Barbour v. State ex rel. Hood,

974 So.2d 232, 240 (Miss. 2008) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Barr v. Delta & Pine Land Co.,

199 So.2d 269 (Miss. 1967) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

Boyd v. Tishomingo County Democrat Executive Committee,

912 So.2d 124, 128 (Miss. 2005) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Caves v. Yarbrough,

991 So.2d 142 (Miss. 2008) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

City of Natchez v. Sullivan,

612 So.2d 1087 (Miss. 1992) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20, 21, 22, 34, 36

Dearman v. Dearman,

811 So.2d 308 (Miss. App. 2001) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

Dialysis Solutions v. Mississippi Department of Health,

96 So.3d 713 (Miss. 2012) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45, 46

Drummond v. State,

185 So. 207 (Miss. 1938) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43, 44, 45

Earle v. Crum,

42 Miss. 165 (1868) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

Fidelity & Guaranty Ins. Co. v. Blount,

63 So.3d 453, 465 (Miss. 2011) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

Gilmer v. State,

955 So.2d 829 (Miss. 2007) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

5

Harpole v. Kemper County Democratic Executive Committee,

908 So.2d 129, 135 (Miss. 2005) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

Hoy v. Hoy,

93 Miss. 732, 48 So. 903, 904 (1909) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

In The Interest of AB, Jr.,

663 So.2d 580 (Miss. 1995) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Jones v. Moorman,

327 So.2d 298 (Miss. 1976) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

Kellum v. Johnson,

237 Miss. 580, 115 So. 2d 147 (Miss. 1959) . . . 14, 15, 23, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 41

McDaniel v. Beane,

515 So. 2d 949, 951 (Miss. 1987) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

Mississippi Department of Transportation v. Allred,

928 So.2d 152 (Miss. 2006) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17, 22

Mississippi Ethics Commission v. Grisham,

957 So.2d 997, 1001 (Miss. 2007) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Mississippi Public Service Commission v. Municipal Energy Agency,

463 So.2d 1056, 1058 (Miss. 1985) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

Mississippi State and School Employees Life and Health Plan v. KCC, Inc.,

108 So.3d 932, 936 (Miss. 2013) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Mississippi State Highway Department v. Haines,

139 So. 168, 171 (Miss. 1932) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

Moore v. Parker,

962 So.2d 558, 562 (Miss. 2007) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Noxubee County Democratic Executive Committee v. Russell,

443 So.2d 1191 (Miss. 1983) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29, 33

Pearson v. Parsons,

541 So.2d 447 (Miss. 1989) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Smith v. Jackson Construction Co.,

607 So.2d 1119 (Miss. 1992) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

6

Southern Pacific Transportation Co. v. Fox,

609 So.2d 357, 362 (Miss. 1992) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

State ex rel. Patterson v. Board of Supervisors of Warren County,

233 Miss. 240, 102 So.2d 198 (1958) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

Tillis v. State,

43 So.3d 1127 (Miss. 2010) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15, 17

Tolliver ex rel. Beneficiaries of Green v. Mladineo,

987 So. 2d 989 (Miss. App. 2007) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

Federal Cases

U. S. Supreme Court

Kucana v. Holder,

558 U.S. 233, 249 (2010) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Nken v. Holder,

556 U.S. 418, 430 (2009) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Rusello v. United States,

464 U.S. 16, 23 (1983) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

United States v. L.A. Tucker Truck Lines, Inc.,

344 U.S. 33 (1952) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42, 43

Wong v. McGrath,

339 U.S. 33 (1950) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42

U.S. Circuit Courts of Appeals

Chertkof v. United States,

676 F.2d 984, 987-88 (4

th

Cir. 1982) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Hazardous Waste Treatment Council v. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency,

861 F.2d 270, 276 (Fed. Cir. 1988) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Mississippi Poultry Association, Inc. v. Madigan,

9 F.3d 1113, 1114 (5

th

Cir. 1993) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

United States v. Wong Kim Bo,

472 F.2d 720, (5

th

Cir. 1972) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

7

U.S. District and Other Federal Courts

Evers v. State Board of Election Commissioners,

327 F.Supp. 640 (D. Miss. 1971) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

Other State Cases

Chase Home Finance, LLC v. Nolan,

2013 Ill. App. 2d 130075-U (2013) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Graffell v. Honeysuckle,

191 P.2d 858 (Wash. 1948) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

In re O.H.,

768 N.E.2d 799, 803 (Ill. App. 2002) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

State v. Budik,

272 P.3d 816 (Wash. 2012) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

Mississippi Statutes and Rules

Laws 1970, Chapter 506 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

Laws 1970, Chapter 508 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

Laws 1979, Chapter 452 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

Laws 1982, Chapter 477 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

Laws 1986, Chapter 495 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

Mississippi Code of 1942, Section 3143 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24, 30, 31

Mississippi Code of 1942, Section 3144 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24, 27, 28, 30, 31, 35

Mississippi Code of 1942, Section 3146 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28, 35

Miss. Code Ann. 23-15-1 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

Miss. Code Ann. 23-15-71 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Miss. Code Ann. 23-15-239 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Miss. Code Ann. 23-15-293 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

8

Miss. Code Ann. 23-15-296 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Miss. Code Ann. 23-15-297 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Miss. Code Ann. 23-15-331 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Miss. Code Ann. 23-15-367 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Miss. Code Ann. 23-15-597 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28, 29, 33

Miss. Code Ann. 23-15-599 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12, 18, 28, 29

Miss. Code Ann. 23-15-911 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12, 29, 33

Miss. Code Ann. 23-15-921 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14, 19, 29, 30, 33, 36, 40

Miss. Code Ann. 23-15-923 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . passim

Miss. Code Ann. 23-15-927 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11, 13, 17, 19, 20, 38, 39, 40, 43, 45, 46

Miss. Code Ann. 23-15-929 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Miss. Code Ann. 23-15-937 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17, 22

Miss. Code Ann. 23-15-1031 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

Miss. Code Ann. 23-15-1111 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13, 26

9

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES

The issues before this Court on appeal are:

Issue I: Does Mississippi Election Code 23-15-923 require that a complaint contesting

a primary election for state-wide office be filed with the political partys state

executive committee within a specific number of days?

Issue II: Does any other section of the Mississippi Election Code require that a complaint

contesting a primary election for state-wide office be filed with the political

partys state executive committee within a specific number of days?

Issue III: Does the absence of a time requirement in Election Code 23-15-923 indicate an

intent by the Legislature that no specific deadline be imposed on filing a

complaint contesting a primary election for state-wide office with the political

partys state executive committee?

Issue IV: When enacting the Mississippi Election Code, did the Legislature express an

intent to repeal Mississippis former election statutes governing primary

elections?

Issue V: Did the Legislatures adoption of the Election Code make material changes in

Mississippis election statutes?

Issue VI: Is the Kellum v. Johnsons interpretation of 1959 Mississippi election statutes

binding precedent on the interpretation of the current Mississippi Election Code?

Issue VII: Is the Kellum v. Johnson decision inconsistent with its own proclaimed well

established principles of statutory construction?

Issue VIII: Did this Court in Barbour v. Gunn interpret and apply Election Code 23-15-

923 consistent with its clear language and contrary to an application of Kellum v.

Johnson as precedent?

10

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. Nature of the Case, Course of the Proceedings, and Disposition in the Court Below.

This is an election contest case. Appellant Chris McDaniel (McDaniel) initiated an

election contest to challenge of the results of the June 24, 2014, Republican Party primary runoff

election for U. S. Senator by filing a complaint with the Republican Party State Executive

Committee (SREC) pursuant to Mississippi Election Code 23-15-923. After giving the

SREC time to consider the complaint, McDaniel filed a petition for judicial review with the

Circuit Court pursuant to Election Code 23-15-927.

In the Circuit Court, Appellee Thad Cochran (Cochran) filed a motion to dismiss the

complaint arguing that McDaniel did not timely file the complaint with the SREC.

Notwithstanding the facts that (1) Election Code 23-15-923 does not impose a time

requirement within which a complaint must be filed, (2) no other section of the Election Code

imposes such a requirement, and (3) Mississippis former election laws were expressly repealed

and restructured more than once over the years by the Legislature, Cochran argued that a 1959

decision of the Mississippi Supreme Court interpreting election statutes (since repealed) under

the Mississippi Code of 1942 imposed a 20-day time requirement within which McDaniel was

required to file his election complaint with the SREC.

The Circuit Court granted Cochrans motion, and the Circuit Courts order dismissing

McDaniels case is the subject of this appeal.

B. Statement of Facts

The Mississippi Republican party held its primary election for U. S. Senator on Tuesday,

June 3, 2014. McDaniel received the highest number of votes and Cochran received the second

highest number of votes, but no single candidate received a majority of the votes cast in that

11

primary. These results were certified to the Mississippi Secretary of State by the Chairman of

the Republican Party State Executive Committee (SREC) on June 13, 2014.

On Tuesday, June 24, 2014, the Mississippi Republican party held a primary runoff

election between McDaniel and Cochran. Thirteen (13) days later (July 7, 2014),

1

the Chairman

of the SREC submitted an initial certification of the results to the Secretary of State, declaring

Cochran to have received the highest number of votes and declaring him the Republican

nominee for U. S. Senator. An amended certification was submitted to the Secretary of State

three (3) days later (July 10, 2014).

Having observed significant irregularities in the handling of the voting process on June

24, as well as the Cochran campaign openly promoting violation of Mississippi election law,

McDaniel looked to challenge the results. He gave notice of his intent to begin examining

election results documentation from the runoff election on July 7, 2014, to the circuit clerks of

the States counties pursuant to Mississippi Code 23-15-911. When that examination began in

the counties, McDaniel encountered multiple obstructions, including among them the complete

refusal to access Hinds County records on July 7, 2014. The chairman of the Republican Partys

county executive committee for Hinds County denied McDaniel all access to election records on

July 7, 2014, stating that he had not yet provided the county executive committees certification

of the results to the SREC.

Over the course of the next twenty-eight (28) days, McDaniel examined county election

records in nearly all of Mississippis 82 counties and assimilated the results of that examination

into a complaint consisting of over 390 pages. When all completed, McDaniels complaint

1

Not within ten (10) days as required by Mississippi Code 23-15-599.

12

summarized election code violations in forty-one (41) counties. McDaniel filed his election-

contest complaint with the SREC pursuant to Mississippi Code 23-15-923 on August 4,

2014. The total time period from the June 24 runoff election until McDaniels filing of the

election-contest complaint with the SREC was forty-one (41) days. This forty-one (41) day

period included the initial thirteen (13) days waiting for the SREC to certify the runoff election

results, and then the twenty-eight (28) days for McDaniel to examine the election records in

Mississippis eighty-two (82) counties and assimilate the results of that examination into his

election-contest complaint filed with the SREC.

On August 14, 2014, McDaniel filed his petition for judicial review with the Jones

County Circuit Court pursuant to Election Code 23-15-927. The following day, Chief Justice

Waller appointed Senior Status Judge Hollis McGehee to preside over the election contest

litigation.

On August 21, 2014, Cochran filed his Answer to the Complaint and a motion to

dismiss. Judge McGehee heard arguments on Cochrans motion to dismiss August 28, 2014.

Judge McGehee granted the motion and ordered dismissal, which order was entered by the

Circuit Clerk of Jones County on September 4, 2014. McDaniel filed his Notice of Appeal to

this Court on September 5, 2014.

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

The Mississippi Election Code, Miss.Code Ann. 23151 through 23151111, is a

comprehensive, detailed set of laws governing all aspects of the election process in the State of

Mississippi. Included in the Election Code are statutes governing the procedures for

challenging primary elections. Election Code 23-15-923 is the section that authorizes

candidates to contest the results of primary elections for multi-county and state-wide offices.

13

Standing alone and in the context of the entire Election Code, 23-15-923 is clear. It does not

impose a specific time requirement within which a complaint must be filed with the political

partys state executive committee to contest a primary election for state-wide office.

A completely separate section of the Election Code authorizes the contest of primary

elections for single county offices. Section 23-15-921 imposes a 20-day deadline for filing a

complaint with a partys county executive committee in such single-county primary elections.

Section 23-15-921 stands in contrast to the multi-county contest statute, 23-15-923, which

clearly omits such a deadline. The language of Section 23-15-921 clearly limits its applicability

to single county offices, as similarly the language of 23-15-923 clearly limits its applicability to

multi-county and state-wide offices. The differentiation between single county offices, on the

one hand, and multi-county and state-wide offices, on the other, is seen throughout the Election

Code. The difference between 23-15-921 and 23-15-923 is just one example of that

differentiation. The absence of a time requirement in 23-15-923 indicates an intent by the

Legislature that no specific time requirement be imposed in the circumstances to which it

applies. As would then be expected, no other section of the Election Code imposes a time

requirement on filing a complaint to contest a primary election for state-wide office.

In the Circuit Court, Cochran argued that the 20-day deadline found in 23-15-921

should be read into (or written by the Court into) 23-15-923. Cochran further argued that this

statutory revision had already been accomplished by this Courts 1959 interpretation of the

Mississippi Code of 1942 in Kellum v. Johnson, 237 Miss. 580, 115 So.2d 147 (1959).

The statutes interpreted by Kellum, along with all other former Mississippi election

statutes, have been repealed. When the Mississippi Legislature enacted the Mississippi Election

Code in 1986, all former Mississippi election statutes (specifically and expressly including the

14

statutes interpreted by Kellum v. Johnson) were expressly repealed, for the third time, in fact,

since the Kellum decision. The Legislatures 1986 repeal of all former Mississippi election laws

and adoption of the Election Code constituted material changes in Mississippis election law. In

the context of the Election Code, 23-15-923 is a new statute that is materially different from

its somewhat similar predecessor. Section 23-15-923 was further amended in 1988. Kellum v.

Johnsons interpretation of a 1959 Mississippi election statute is therefore not authoritative nor

a controlling precedent on the interpretation of the current Mississippi Election Code - a

conclusion confirmed by this Courts decision in Barbour v. Gunn, 890 So.2d 843 (Miss. 2004).

Kellum v. Johnson is internally inconsistent. Applying the principles of statutory

construction announced by Kellum itself shows that Kellum was wrongly decided at the time it

was made.

In 2004, this Court applied 23-15-923 consistent with its clear language and consistent

with recognized principles of statutory construction in Barbour v. Gunn, which application was

inconsistent with an application of Kellum v. Johnson as precedent.

The Circuit Court erred in dismissing McDaniels Complaint. For all these reasons, the

opinion of the court below should be reversed.

ARGUMENT

The issues raised by this appeal are issues of law requiring the interpretation of statutes.

This Court employs a de novo standard in reviewing issues of law and the interpretation of

statutes on appeal. Moore v. Parker, 962 So.2d 558, 562 (Miss. 2007); Boyd v. Tishomingo

County Democrat Executive Committee, 912 So.2d 124, 128 (Miss. 2005); Tillis v. State, 43

So.3d 1127 (Miss. 2010).

15

I. Election Code 23-15-923 does not impose a specific time requirement for filing a

complaint with a partys state executive committee to contest a primary election

for state-wide office.

The Mississippi Election Code provides the procedural remedy for a candidate seeking to

contest the election of another in a party primary. In Article 29 Election Contest and

Subarticle B Contests of Primary Elections, Section 23-15-923 provides:

State, congressional, judicial, legislative offices.

Except as otherwise provided in Section 23-15-961, a person

desiring to contest the election of another returned as the nominee

in state, congressional and judicial districts, and in legislative

districts composed of more than one (1) county or parts of more

than one (1) county, upon complaint filed with the Chairman of

the State Executive Committee, by petition, reciting the grounds

upon which the election is contested. If necessary and with the

advice of four (4) members of said committee, the chairman shall

issue his fiat to the chairman of the appropriate county executive

committee, and in like manner as in the county office, the county

committee shall investigate the complaint and return their findings

to the chairman of the state committee. The State Executive

Committee by majority vote of members present shall declare the

true results of such primary.

The language 23-15-923 is clear in the statement of its applicability, authorization, and

limitations. That language specifies, among other things, (1) that it authorizes a person desiring

to contest the election of another as nominee, (2) that it applies and is limited to elections for

nominees in state, congressional, judicial districts, and legislative districts composed of more

than one county or parts of more than one county; (3) that an election-contest authorized by this

section must be initiated by filing a complaint with the Chairman of the State Executive

Committee, and (4) that while the complaint must recite the grounds upon which the election is

contested, the statute does not require any specific category or type of ground be recited.

Equally clear in the language of 23-15-923 is the fact that it does not impose a requirement

that the election-contest complaints authorized thereunder be filed within a specified period of

16

time.

Section 23-15-923s limitation to multiple county elections distinguishes it from other

Election Code sections that apply to single county offices. The Legislature made a distinction

throughout the Election Code between primaries involving single county offices and those

involving multi-county and state-wide offices. See, for example, 23-15-293, 23-15-297,

23-15-331, 23-15-927, and 23-15-937. Section 23-15-923 is tailored to fit into the statutory

scheme that places different requirements on single county office primaries than those placed on

elections for offices involving multiple counties, parts of several counties (such as legislative

districts) and the entire State. The absence of a time requirement is one part of 23-15-923's

tailoring to fit contests of multi-county and state-wide offices into the overall statutory scheme.

When a statute is clear, the Court applies the plain meaning of the statute. Tillis v. State,

43 So.3d 1127 (Miss. 2010). The Court is not to enlarge or restrict a statute where the meaning

of the statute is clear. Barbour v. State ex rel. Hood, 974 So.2d 232, 240 (Miss. 2008); Gilmer

v. State, 955 So.2d 829 (Miss. 2007). Courts have a duty to give statutes a practical application

consistent with their wording, unless such application is inconsistent with the obvious intent of

the legislature. Mississippi State and School Employees Life and Health Plan v. KCC, Inc., 108

So.3d 932, 936 (Miss. 2013); Mississippi Ethics Commission v. Grisham, 957 So.2d 997, 1001

(Miss. 2007). What the Legislature says in the text of the statute is considered the best evidence

of the legislative intent. Mississippi Department of Transportation v. Allred, 928 So.2d 152

(Miss. 2006).

17

II. Other sections of the Election Code impose many deadlines but none on filing a

complaint to contest a primary election for state-wide office with a political partys

state executive committee.

The Election Code is filled with specific deadlines and time requirements, many of which

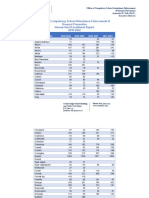

were added or amended in the adoption of the Election Code in 1986. Attached Addendum A

is a tabulation of selected Election Code sections that impose notable deadlines and time

requirements.

2

This tabulation may be compared to the Secretary of States 2014 Elections

Calendar which presents many of the deadlines and time requirements taken from the Election

Code.

3

Examples of time requirements found in the Election Code include:

- 23-15-71: Two (2) days specified as time within which an aggrieved elector may

file a bill or exceptions to a decision of election commissioners.

- 23-15-239: Not less than five (5) days prior to each election county executive

committees must conduct training sessions for precinct managers.

- 23-15-296: Within two (2) working days of each qualifying deadline political

parties must provide the Secretary of State information on candidates who

submitted qualifying papers.

- 23-15-367: The Secretary of State must provide county election commissioners a

sample official ballot not less than fifty-five (55) days prior to the election.

- 23-15-599: Within ten (10) days after a primary election, the chairman of the

partys state executive committee must transmit a tabulated statement of the

votes to the Secretary of State.

These are but a few of the examples which demonstrate that the Legislature enacted in the

Election Code a coordinated and interdependent system of time requirements in an effort to

effectively regulate the administration of elections in Mississippi. Within that coordinated

2

Addendum A does not attempt to be a comprehensive coverage of every deadline and time requirement

in the Election Code.

3

Published at

http://www.sos.ms.gov/links/elections/2014/2014%20Elections%20Calendar%20web_Rev%209%202013.

pdf (accessed September 11, 2014).

18

system of time requirements, no Code section imposes a time requirement or deadline for filing a

complaint to contest a primary election for state-wide office with a political partys state

executive committee.

Section 23-15-921 provides an example of both a specific time requirement in the

Election Code and also an example of the Election Codes differentiation between single county

offices and multi-county offices. The language of 23-15-921 specifies:

(1) That it applies to elections for nominees to any county office, county district

office, or legislative district composed of one county or less;

(2) That an election contest authorized by this section must be initiated by filing a

complaint with the county executive committee in the county in which the

election was held; and

(3) That such election contest must be filed within twenty (20) days after the

primary election.

In coordinating the regulation of primary election contests, the Legislature again made

distinction between elections for offices involving a single county and those elections involving

more than one county, such as legislative district and state-wide offices. For single county

offices, the Legislature imposed in 23-15-921 a requirement that an election-contest complaint

be filed with the county executive committee within twenty (20) days after the primary elections.

In contrast, the Legislature chose to not impose a deadline for contesting primary

elections for multi-county offices. The absence of a deadline from 23-15-923 makes it similar

to other sections of Election Code that do not impose a time requirement. Among them is 23-

15-927. Section 23-15-927 governs the process of filing a petition for judicial review of an

executive committees decision. Before 2012, 23-15-927 did not impose a deadline for filing a

petition for judicial review. Section 23-15-927 required only that a candidate file his petition for

judicial review forthwith after the conclusion of the executive committees proceeding.

19

Interpreting 23-15-927, the Mississippi Supreme Court has held that the statute imposes no

fixed time limit, but rather the meaning of the term forthwith depends upon consideration of

the surrounding facts and circumstances and varies with each particular case. Pearson v.

Parsons, 541 So.2d 447 (Miss. 1989).

III. The absence of a deadline in Election Code 23-15-923 is evidence of an intent by

the Legislature that no specific time requirement be imposed.

As noted above, the Legislatures adoption of specific time requirements in specific

circumstances is seen throughout the Election Code. Where specific time requirements were

thought necessary, the Legislature adopted them. Similarly, the Legislature omitted specific

time requirements from the Election Code where discretion and flexibility were considered

important. An example of the latter is 23-15-929, which provides that the contestee must file

an answer, but does not specify any specific number of days. Both adoption and omission of

time requirements are part of the Legislatures overall coordination of the Election Code.

The significance of the Legislatures decision to omit specific time requirements was

articulated by the Mississippi Supreme Court in City of Natchez v. Sullivan, 612 So.2d 1087

(Miss. 1992). The Court stated, the omission of language from a similar provision on a similar

subject indicates that the legislature had a different intent in enacting the provisions, which it

manifested by the omission of the language. Id. at 1089. The principle was applied again in In

The Interest of AB, Jr., 663 So.2d 580 (Miss. 1995), where the Court stated: This Court will

not second guess the legislature by reading such a requirement into the statute.

It is an accepted canon of statutory construction that the express inclusion of a

provision in one section of a statute and an omission of that provision in a parallel section of the

statute demonstrates the legislature's intent to omit the provision in the parallel section. Chase

20

Home Finance, LLC v. Nolan, 2013 Ill. App. 2d 130075-U (2013); In re O.H., 768 N.E.2d 799,

803 (Ill. App. 2002). See also, Kucana v. Holder, 558 U.S. 233, 249 (2010); Nken v. Holder,

556 U.S. 418, 430 (2009); Rusello v. United States, 464 U.S. 16, 23 (1983); Mississippi

Poultry Association, Inc. v. Madigan, 9 F.3d 1113, 1114 (5

th

Cir. 1993); United States v. Wong

Kim Bo, 472 F.2d 720, (5

th

Cir. 1972). An intentionally omitted term from one section cannot

legitimately be read into another section, where it is clearly absent. Hazardous Waste Treatment

Council v. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 861 F.2d 270, 276 (Fed. Cir. 1988);

Chertkof v. United States, 676 F.2d 984, 987-88 (4

th

Cir. 1982).

This Courts holding in City of Natchez v. Sullivan accurately describes the Mississippi

Legislatures approach to regulating primary election contests. The omission of a set time

period from 23-15-923 was intentional. That intent is further evidenced by a perusal of the

Election Codes overall regulation of party primary elections. The regulation of primary

elections involving multi-county and state-wide offices is obviously more complicated than

regulating those involving single county offices. A candidate contesting a primary election for a

single county office must deal with one county executive committee and one circuit clerk to

review records. This is a relatively straight-forward affair, and the amount of time required to

prepare a contest can be estimated with some degree of confidence.

In contrast, the contest of a primary election for a multi-county or state-wide office

requires dealing with multiple different county executive committees, circuit clerks (up to 82 in a

state-wide contest), and then the partys state executive committee. The time necessary to

prepare such an election contest is largely unpredictable and need not be specified. Other

sections of the Election Code provide incentive for the candidate pursuing such a challenge to

prepare his challenge as quickly as reasonably possible. Section 23-15-937 likely provides all

21

the incentive required to motivate an election challenger to file a complaint as soon as possible,

as it provides that if a final decision on an election contest is not made by the time the official

ballots are required to be printed, the name of the nominee declared by the party executive

committee shall be printed on the official ballots as the party nominee.

Election Code 23-15-923 must be read in the context of the entire Election Code.

Statutes that address the same subject or are part of a single legislative act must be read

together. Mississippi Department of Transportation v. Allred, 928 So.2d 152, 155

(Miss.2006).

While it is clear that 23-15-923 does not impose a time requirement, if there were any

ambiguity, the intent of the Legislature is made clear by reading the Election Code as a whole.

This Court has held that statutes dealing with the same or similar subject matter must be read in

pari materia and to the extent possible, each section of the Code must be given effect. Fidelity

& Guaranty Ins. Co. v. Blount, 63 So.3d 453, 465 (Miss. 2011)(citing Mississippi Public

Service Commission v. Municipal Energy Agency, 463 So.2d 1056, 1058 (Miss. 1985)).

The absence of a deadline from 23-15-923 gives effect to the section and fits in the

framework created by the Election Code. The principle of statutory construction articulated in

City of Natchez v. Sullivan harmonizes sections of the Election Code. The absence of a specific

time in 23-15-923 provides a flexibility that is commensurate with the scope of the office or

election being challenged. To specify a single time period for all contests authorized by 23-15-

923 would cause contests of state-wide primaries to be treated the same as small districts

(though multi-county) primaries and create conflicts in timing of events specified in the Code.

22

IV. The Mississippi Legislature clearly expressed an intent to repeal former Mississippi

election laws regulating primary elections.

The history of Mississippis Election Code is complicated, but one fact from that history

stands out clearly, the Mississippi Legislature intended to repeal Mississippis former election

statutes and to restructure Mississippis election laws governing primary elections

On April 6, 1970, the Mississippi Legislature adopted House Bill 362 with the express

purpose to adopt:

AN ACT to amend Sections 3107-04, 3108.5, 3118.5, 3118.7,

3121, 3123, 3152, 3153, 3209.5, 3226, 3237, 3238, 3239, 3261,

3263, 3279, 3280, 3281, 3286.5, 3313.5, and 3315, Mississippi

Code of 1942, and to repeal Section 3105, 3107-03, 3107-05,

3107-07, 3108, 3109, 3110, 3111, 3112, 3113, 3114, 3115, 3116,

3117, 3118, 3119, 3124, 3125, 3126, 3127, 3128, 3129, 3130,

3131, 3132, 3133, 3134, 3135, 3136, 3137, 3138, 3140, 3141,

3142, 3143, 3144, 3145, 3146, 3147, 3148, 3149, 3150, 3151,

3154, 3155, 3156, and 3157, Mississippi Code of 1942, to make

the code conform to the provisions of House Bill No. 363,

Regular Session of 1970, which abolished political primary

elections; and for related purposes.

See Laws 1970, Chapter 506 (emphasis added).

4

The referenced House Bill No. 363 abolished

political primary elections and contained provisions setting out the method for qualifying as

candidates for persons affiliated with political parties. Laws 1970, Chapter 508. Shortly after

the adoption of Chapters 506 and 508, the new law was challenged in federal court under

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

5

See Evers v. State Board of Election

Commissioners, 327 F.Supp. 640 (D. Miss. 1971). In Evers, the federal court issued an

injunction that blocked the new law from taking effect. At the time of the Evers decision, the

4

Sections 3143 and 3144 of the Mississippi Code of 1942 are discussed below.

5

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 (89 P.L. 110, 79 Stat. 437 (Aug. 6, 1965)) was formerly codified at 42

U.S.C. 1973c but now codified at 52 U.S.C. 10301. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is another major

change in election law that took place after Kellum v. Johnson was decided in 1959, as discussed below.

23

United States Department of Justice had not approved or disapproved Chapter 506. Nearly

three (3) years later, on April 26, 1974, the Department of Justice disapproved Chapter 506.

See also Jones v. Moorman, 327 So.2d 298 (Miss. 1976)(recognizing the history of Chapters

506 and 508 of the Laws of 1970).

In 1979, the Mississippi Legislature again adopted legislation that would repeal the

States former statutes relating to party primary elections. On March 30, 1979, the Legislature

adopted Senate Bill No. 2802 as:

AN ACT to . . . repeal 3105, 3107-03, 3107-04, 3107-05, 3108,

3108.5, 3109, 3110, 3111, 3112, 3113, 3114, 3115, 3117, 3118,

3118.5, 3118.7, 3123, 3124, 3126, 3127, 3129, 3137, 3142

through 3157, 3169, 3261, 3279, 3281, 3313.5, 3315, and 3374-

63, Mississippi Code of 1942, as they existed prior to November

1, 1964, and Sections 23-1-9, 23-1-27, 23-1-31, 23-1-39, 23-1-

65, 23-3-23, 23-5-135, 23-5-169, 23-5-173, 23-5-241 and 23-5-

245, Mississippi Code of 1972, which relate to political party

primaries; and for related purposes.

See Laws 1979, Chapter 452 (emphasis added).

6

This Act of the Legislature was blocked by

disapproval from the United States Department of Justice under Section 5 of the Voting Rights

Act of 1965.

On April 22, 1982, the Mississippi Legislature adopted House Bill 828 to adopt:

AN ACT to amend Sections 3109, 3111 and 3152, Mississippi

Code of 1942, to provide that the first political party primary

election shall be held seven weeks before the general, regular or

municipal general election and that the second political primary

election, if necessary, shall be held three weeks thereafter; to

amend Section 23-5-134, Mississippi Code of 1972, to provide

that independents shall qualify for an election at the same time as

political party candidates; to repeal Section 3260A, Mississippi

Code of 1942, which provides for the form of the ballot and the

6

Sections 3143 and 3144 of the Mississippi Code of 1942, discussed below, are included in the

emphasized block of repealed sections, and specifically enumerated in Section 38 of the adopted Senate

Bill 2802.

24

manner of qualifying as a candidate; to repeal Section 3260,

Mississippi Code of 1942, which provides for the content of

ballots and the manner of qualifying for United States Senator and

United States Representative; to repeal Chapter 452 of the Laws

of the General Session of 1979, which provides for the open

primary form of election; and for related purposes.

Laws 1982, Chapter 477 (emphasis added). This Act was also blocked by disapproval from the

United States Department of Justice under Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

By the time the Voting Rights of 1965 was amended in 1982,

7

the Mississippi

Legislature had gone through at least two (2) iterations of repealing and restructuring the States

election laws governing primary elections, both of which had been rejected by the U. S.

Department of Justice.

In the spring of 1984, then Secretary of State Dick Molpus appointed a 25-member

Election Law Reform Task Force to rewrite Mississippi's election law. With a generalized

assignment to recodify Mississippi election law, the Task Force held public hearings in each of

the state's five congressional districts receiving testimony and written recommendations from a

wide variety of interest groups. Based upon this testimony, the Task Force perceived a need to

broaden its underlying assignment of recodification and to undertake the task of rewriting

substantial portions of then existing law. R. Andrew Taggart & John C. Henegan, The

Mississippi Election Code of 1986: An Overview, 56 Miss. L. J. 536, 537-539 (1986).

Over an approximately two year period, the process of rewriting Mississippis election

law worked its way through the Task Force, through the 1985 session of the Legislature, and

then through the Joint Interim Study Committee of the Mississippi Legislature formed in 1985

and tasked with additional study of the States election laws and making proposals for reform.

7

97 Pub. L. 205, 96 Stat. 134 (June 29, 1982).

25

In the 1986 Legislative Session, the Joint Interim Study Committee of the Mississippi

Legislature made its proposal to make significant changes to the States election laws, including

repealing all for former election statutes and consolidating all of the States election laws into a

coordinated, single Election Code that was codified in a single chapter of the Mississippi Code.

On April 16, 1986, the Mississippi Legislature adopted Senate Bill 2234 (Laws 1986,

Chapter 495). The preface Senate Bill 2234 (copy attached hereto as Addendum B) provides

a picture of the expansive scope of the 1986 Act. Section 1 (now codified at Mississippi Code

23-15-1) provided This act shall be known and may be cited as the Mississippi Election

Code. Sections 331 through 345 of the Act repealed election laws formerly found in Chapters

1 - 11 of Title 23 of the Mississippi Code of 1972. Section 346 of the Act provided that

Sections 3105 through 3157, Mississippi Code of 1942, which relate to political party primary

elections, are hereby repealed. In that grouping, Sections 3143 and 3144 of the Mississippi

Code of 1942, discussed below, were again expressly repealed. Then, Section 348 of the 1986

Act provided that All election laws in conflict with the provisions of this act are hereby

repealed. Section 348 is now codified at Mississippi Code 23-15-1111.

The 1986 Act (chapter 495, Laws of 1986) was submitted on November 3, 1986, to the

Attorney General of the United States for consideration and preclearance under the provisions

of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended and extended. On December 31, 1986, and on

January 2, 1987, the Attorney General of the United States interposed no objections to the

changes involved in chapter 495, Laws of 1986, thereby implementing the effective date of

January 1, 1987, of the Mississippi Election Code. See also McDaniel v. Beane, 515 So. 2d

949, 951 n.1 (Miss. 1987). The Election Code as enacted by the 1986 Act continues in effect,

though additional changes have been made to specific sections, one of which is 23-15-923.

26

V. The Election Code made material changes in Mississippis election statutes and

specifically to the predecessors of 23-15-923.

Changes made by the 1986 Act and subsequent amendments now reflected in the

Election Code are sweeping and restructuring in nature. Attached Addendum A presents a

limited picture of those changes, a picture that is focused on changes in time requirements and

related new sections added by the 1986 Act or subsequent amendments. While it is obvious

from a perusal of the former and current election statutes that the draftsmen of the 1986 Act

used the form of the old statutes as a starting point for some of the new laws, this fact should

not be allowed to obscure the substantiality of the changes the Election Code. These changes

affected both the overall structure and specific sections of the election law. Comparing the

identified sections of the Code of 1942 with the related current sections of the Election Code,

Addendum A demonstrates by sample the significance of the number of time requirements that

were added or changed by the 1986 Act and subsequent amendments. Addendum A identifies

47 different former election code sections that the 1986 Act or subsequent amendments changed

by adding a new time requirement or by modifying an old time requirement.

The changes most pertinent to the interpretation of Election Code 23-15-923 are of

two types. The first type is changes in the language and structure that resulted in the current

23-15-923. The second type is changes of time requirements in other sections that affect the

time in which a challenger has access to election records.

The differences in language and structure between Election Code 23-15-923 and its

predecessor (Section 3144 of the Mississippi Code of 1942) may be seen graphically in the side-

side comparison presented in Addendum C. The differences may be described generally as

follows: Section 3144 was by indirect language limited to allegations of fraud as the grounds for

27

an election contest. Election Code 23-15-923 covers entire classes of other grounds for

contesting primary elections that Section 3144 did not. Section 3144 did not include exceptions

or other language coordinating it with other election statutes. Election Code 23-15-923

includes both. Section 3144 did not apply to legislative districts composed of more than one

county or parts of more than one county. Election Code 23-15-923 does. The language of

23-15-923 makes an even clearer delineation of its applicability to multi-county primaries by the

addition of the language and in legislative districts composed of more than one county or parts

of more than one county. Section 3144 applied to flotorial contests. Election Code 23-15-

923 does not.

The structural differences are equally significant. Section 3144 did not specify who

could file a complaint. Nor did it directly describe the purpose for which a complaint could be

filed. Election Code 23-15-923 is structured materially different. It first includes language

coordinating 23-15-923 with other sections of the Election Code. Then the new language

addresses both who may file and what must be recited in the complaint. Section 23-15-923 is

structurally independent.

Changes in other code sections made 23-15-923's cooperation with other parts of the

Election Code different than Section 3144. In the 1986 adoption of the Election Code, the

political party state executive committees were given ten (10) days after a primary election to

certify the results to the Secretary of State. See Election Code 23-15-599. Prior to the

adoption of the Election Code in 1986, the election statutes did not impose such a time

requirement on the state executive committees. See 3146, Mississippi Code of 1942.

The Election Codes coordination between sections produces an expected time-sequence

of events in primary elections for multi-county offices. Section 23-15-597 requires that political

28

party county executive committees (hereinafter CEC) meet on the first or second day after the

election to canvass returns, declare the result for their county and then transmit the county

results to the partys state executive committee within 36 hours after the CEC has declared the

county results. This procedure consumes the first 4 days after the primary election.

Section 23-15-599 then requires the state executive committee to transmit the state-wide

results to the Secretary of State within 10 days from the date of the primary election. This

deadline is calculated from the date of the election, not from the date of the CECs transmittal of

results. Under 23-15-597, a state executive committee should have received the CEC results

within 4 days of the date of the primary election. The state executive committee would then

have, under 23-15-599's ten day deadline, at least 6 days to prepare its own certification to the

Secretary of State. That these requirements apply to primaries for United States Senator,

Election Code 23-15-1031 makes clear.

The date of the state executive committees certification to the Secretary of State

initiates the 12-day window within which a candidate may examine election-results

documentation under 23-15-911 in state wide elections. This is a corollary to the CEC

certification under 23-15-597 initiating the examination period in a single county primary

election. See Election Code 23-15-1031; Noxubee County Democratic Executive Committee

v. Russell, 443 So.2d 1191 (Miss. 1983). In this setting, the candidates right to examine the

documents does not begin until 10 days after the primary election and does not conclude until 22

days after the date of the primary election.

29

VI. Kellum v. Johnsons interpretation of the 1959 Mississippi election statutes is not

binding precedent on the interpretation of the current Mississippi Election Code.

In the Circuit Court, Cochran argued that the 20-day deadline found in 23-15-921 had

been read into (or written by the Court into) 23-15-923 by this Courts 1959 interpretation of

the Mississippi Code of 1942 in Kellum v. Johnson, 237 Miss. 580, 115 So.2d 147 (1959).

Kellum v. Johnson dealt with the two statutory sections that addressed election contests in

1959. The first was Section 3143 of the Mississippi Code of 1942. Although it bears some

similarity to current Election Code 23-15-921, the differences are substantial. Section 3143

was limited to allegations of fraud. Election Code 23-15-921 is not limited to allegations of

fraud, but rather includes and applies to grounds for contesting primary elections that Section

3143 did not. Next, Section 3143 did not include exceptions or other language coordinating it

with other election statutes. Election Code 23-15-921 includes both. Third, Section 3143 did

not by its terms apply to legislative districts composed of one county or less. Election Code

23-15-921 does. Fourth, Section 3143 was not clear as to which county executive committee

could accept the subject election dispute petition. The language of Election Code 23-15-921

indicates which county executive committee. The most significant distinction however is that

Section 3143, as it then existed, was repealed in 1986. It was not re-enacted. Rather, a new

statute was enacted. That new statute is Election Code 23-15-921.

The second statutory section Kellum dealt with was Section 3144 of the Mississippi

Code of 1942. It bears some similarity to Election Code 23-15-921, but the differences,

discussed above, are substantial.

The Kellum decision recognized that, in 1959, Section 3143 governed election contests

for primaries for single county and beat offices, while Section 3144 governed election contests

30

for primaries for multi-county offices. The election at issue in Kellum was a multi-county office

- the office of district attorney. The Kellum decision further recognized that Section 3143

contained a time requirement that election contests for single county offices be filed with the

CEC within 20 days after the primary election, while Section 3144 did not contain such a time

requirement for multi-county offices. The Kellum court took the 20-day deadline from Section

3143 (applicable only to single county elections) and inserted it into Section 3144, thereby

judicially creating a basis for applying a 20-day deadline to the primary election for district

attorney there at issue.

The single similarity between the scenario in Kellum v. Johnson and the case sub judice

is obvious: the single county statute included a 20-day deadline and the multi-county statute

contained no deadline. This similarity has no effect on the material changes made to

Mississippis election statutes, including the two sections interpreted by Kellum, since the

Kellum case was decided. These substantial and material changes in the statutes effectively set

aside Kellum v. Johnson as precedential authority for interpreting the current Election Code.

See Southern Pacific Transportation Co. v. Fox, 609 So.2d 357, 362 (Miss. 1992).

In the Circuit Court, Cochran argued that the Kellum v. Johnson interpretation was

incorporated into re-enactement of the election statutes. However, the case authority relied on

by Cochran in making such argument requires, as the foundational element, that a statutory re-

enactment be without change or without material change between the old and new statutes.

See, for example, Caves v. Yarbrough, 991 So.2d 142 (Miss. 2008); Barr v. Delta & Pine Land

Co., 199 So.2d 269 (Miss. 1967); Hoy v. Hoy, 93 Miss. 732, 48 So. 903, 904 (1909); Dearman

v. Dearman, 811 So.2d 308 (Miss. App. 2001). See generally, Smith v. Jackson Construction

Co., 607 So.2d 1119 (Miss. 1992) (Robertson concurring). The rule stated in this line of cases

31

rests on a foundation that the two statutes be exactly the same or the same in all material

respects. Faced with this difficulty, Cochrans argument strained to minimize the differences

between the former election statutes and the current Election Code and to downplay the clear

language of the 1986 adoption of the Election Code. Those differences cannot be ignored. Nor

are they minimized by similarities between the former and current statutes.

When there is a material change between a repealed statute and a newly enacted one, the

cases relied on by Cochran do not apply. From research for this case, it appears that the

Mississippi Supreme Court has not addressed the situation directly, but the principle is so well

ingrained it appears to have been accepted by Mississippi election officials who have looked at

the history of Mississippi election law. None other than Secretary of State Delbert Hosemann,

Mississippis chief election official, concluded that 23-15-923 did not require Chris McDaniel

to file his election-contest complaint with the SREC within any specific number of days. See

Record Supp. at page 6.

When the Supreme Court of Washington faced the issue, it recognized that a change in

statutory law indicates that the Legislature had in mind a mischief and a remedy. It further

held that in construing statutes which reenact or repeal other statutes, or which contain revisions

or codification of earlier laws, where a material change is made in the wording of a statute, a

change in legislative purpose must be presumed. Graffell v. Honeysuckle, 191 P.2d 858 (Wash.

1948). See also State v. Budik, 272 P.3d 816 (Wash. 2012) quoting Graffell and applying the

same rule.

If this Court were to apply Kellum v. Johnson to the current Election Code, a conflict in

the statutory scheme would be created, where none otherwise exists. It would impose a

requirement that candidates in multi-county or state-wide election contests file their complaint

32

with the state executive committee before the end of their allowed 12-day period to examine

election records. In that setting, the candidate would be required to file his complaint 2 days

before the end of the examination period. In the real factual circumstances of the instant case,

McDaniel would have been required to file 5 days before the end of his 12-day examination

period - and for 3 of those days, Petitioners loss would have been caused by the state executive

committees failure to meet the requirements of the Election Code.

Such conflict created by application of Kellum would also be contrary to the intent of the

Legislature as expressed for single county election contests. The time frames set forth in the

Election Code sections applicable to single county election contests indicate that the Legislature

allowed time for a candidate to prepare his election-contest complaint after the 12-day

examination period had expired. Under 23-15-597 CECs are required to meet on the first or

second day after the primary election, canvass the returns, and announce the nominee. This

announcement by the CEC is a certification that triggers the 12-day period pursuant to 23-15-

911 within which a candidate may complete a full examination of the election-results

documentation. Noxubee County Democratic Executive Committee v. Russell, supra. When

23-15-911 and 23-15-597 are read together, it is clear that the process of CEC certification

and candidate review of election records for a single county primary could take from as little as

2 days up to a maximum of 14 days after the primary election date. If a candidate decides, after

reviewing the election documentation, to contest the single-county primary election results,

23-15-921 requires that the candidate file a petition with the CEC within 20 days after the

primary election. The three Election Code sections, 23-15-597, 23-15-911, and 23-15-

921 are coordinated in their application to primary elections for single county offices. Pursuant

to them, a candidate would have, after the conclusion of his 12-day document-examination

33

window, a minimum of 6 days and a potential maximum of 18 days (depending on how long it

took the executive committee to certify results and the candidate to review election records) to

prepare his election-contest complaint and get it filed with the CEC.

The holding of City of Natchez v. Sullivan teaches that the Legislatures omission of a

time requirement from 23-15-923 indicates a legislative intent that a candidate in a multi-

county election contest similarly have some reasonable time (intentionally not specified) after his

12-day examination period within which to file his election-contest complaint with the state

executive committee. In another election case, this Court observed the necessity for a candidate

to examine election records before filing an election-contest complaint, posing the definitive

question: How could [the candidate] file a protest with the [executive committee] before he

obtained evidence via the examination of the ballot boxes? Harpole v. Kemper County

Democratic Executive Committee, 908 So.2d 129, 135 (Miss. 2005).

In sum, material changes in the law adopted by the Legislature in the Election Code have

made Kellum v. Johnsons interpretation of the former election statutes no longer applicable.

VII: Kellum v. Johnson was inconsistent with well-settled principles of law when it was

decided.

The Kellum decision states that it was applying the following principles of statutory

construction:

[D]ifferent parts of a statute reflect light upon each other, and

statutory provisions are regarded as in pari materia where they are

parts of the same act. Hence, a statute should be construed in its

entirety, and as a whole.

. . .

All parts of the act should be considered, compared, and

construed together.

. . .

34

Statutes should, if possible, be given a construction which will

produce reasonable results, and not uncertainty and confusion.

. . .

In construing statutes, the courts should not convict the

Legislature of unaccountable capriciousness.

237 Miss. at 585-86, 115 So.2d at 149-50. These are long established and often acknowledged

principles of statutory construction. See, for example, Adams v. Yazoo & M.V.R. Co., 75 Miss.

275, 22 So. 824 (1897)(A statute must receive such a construction that it will, if possible, make

all of its parts harmonize with each other and render them consistent with its purpose and

scope.) One year before Kellum, the Court had held, The legislative intent must be ascertained

from the provisions of the statute as a whole, and not from a segregated portion considered

apart from the rest of the statute. State ex rel. Patterson v. Board of Supervisors of Warren

County, 233 Miss. 240, 102 So.2d 198 (1958).

At the time Kellum was decided, Section 3143 of the Mississippi Code of 1942 applied

to contests of primary elections involving single county offices. That section required that any

such contest be filed with the county executive committee within 20 days after the primary

election. At the same, Section 3144 applied to contests of primary elections involving multi-

county offices and required that such contests be initiated by filing a complaint with the

appropriate state executive committee. Section 3144 did not impose a deadline for filing a

complaint. Also at that time, Section 3146 did not impose a deadline by which a state executive

committee was required to report the results of any multi-county primary election to the

Secretary of State.

By re-writing Section 3144 to insert a 20-day time requirement on candidates for state-

wide offices, the Kellum court did not construe all the related statutes together so as to give the

statutes a construction which produced a reasonable result. The Kellum decision gave a

35

candidate for state-wide office less time to review election records from 82 counties and prepare

his complaint than the Legislature had given candidates for single county offices. The

candidates for single-county offices were not required to wait on a state executive committee. If

the Kellum court had let different parts of a statute reflect light upon each other, it would have

seen that the omission of language from a similar provision on a similar subject indicates that

the legislature had a different intent in enacting the provisions, which it manifested by the

omission of the language. City of Natchez v. Sullivan, 612 So.2d 1087, 1089 (Miss. 1992).

Were this court to adopt Kellums reasoning and apply it to the current Election Code to

impose the same time requirement for multi-county contests that the Legislature adopted for

single-county contests, it would accuse the Legislature of unaccountable capriciousness. Such

imposition would create an irreconcilable conflict in the statutory scheme where none existed as

adopted by the Legislature. It would be confusing to set a time period of 22 days after a

primary election within which a candidate may review election records for the purpose of

determining whether to file an election contest (the first 10 of which a candidate must wait for

the state executive committee to certify the results of an election), but then require the candidate

to prepare and file his election dispute complaint within 20 days after the primary election - 2

days before the end of the period allowed for an initial examination of election records.

It is clear from a broader look at the system adopted in the current Election Code that

the Legislature is not guilty of such a charge. The different parts of the current Election Code

do reflect light upon each other and should be read as a whole. The omission of a specific time

requirement from 23-15-923, in light of a specific time requirement in 23-15-921, indicates

that the Legislature intended to leave unspecified the amount of time a candidate in a multi-

county contest has to file his complaint with the state executive committee. It would be obvious

36

to a casual observer (and certainly obvious to the States legislators) that a candidate for an

office covering a single county would not require as much time to discover facts and prepare a

complaint as a candidate for a state-wide office. The latter, to prepare his complaint, must

examine election returns for up to 82 counties and then synthesize that examination into an

election-contest complaint to be filed with the state executive committee.

VIII. If Kellum v. Johnson had any precedential value after the comprehensive overhaul

of the Election Code in 1986, it would have been followed in Barbour v. Gunn .

Cochrans argument that McDaniel was required to file his election-contest complaint

with the SREC within 20 days of the primary runoff flies in the face of Barbour v. Gunn, 890

So.2d 843 (Miss. 2004). In Barbour v. Gunn,, Jep Barbour and Phillip Gunn sought the

Republican nomination for House District 56 of the Mississippi House of Representatives.

The primary was held on August 5, 2003. After a close race, Jep Barbour was certified the

winner of the primary election.

On September 8, 2003, 34 days after the primary election, Phillip Gunn filed a challenge

to the primary election with the SREC pursuant to Miss. Code Ann. 23-15-923. Said statute

then read as follows:

23-15-923. State, congressional, judicial, legislative offices

Except as otherwise provided in Section 23-15-961, a person

desiring to contest the election of another returned as the nominee

in state, congressional and judicial districts, and in legislative

districts composed of more than one (1) county or parts of more

than one (1) count, upon complaint filed with the chairman of the

State Executive Committee, by petition, reciting the grounds upon

which the election is contested. If necessary and with the advice of

four (4) members of said committee, the chairman shall issue his

fiat to the chairman of the appropriate county executive

committee, and in like manner as in the county office, the county

committee shall investigate the complaint and return their findings

to the chairman of the state committee. The State Executive

Committee by majority vote of members present shall declare the

37

true results of such primary.

Pursuant to Phillip Gunns (now Speaker of the House of Representatives and

hereinafter referred to as Speaker Gunn) challenge, the SREC met with him and Jep Barbour.

The SREC received the challenge complaint and concluded that it had jurisdiction and set a date

for hearing the challenge. The date that the SREC agreed to hear the challenge was October 2,

2003. One day after setting the hearing date before the SREC, Speaker Gunn sought judicial

review pursuant to 23-15-927 of the Miss. Code Ann. which states:

23-15-927 Petition for judicial review

When and after any contest has been filed with the county

executive committee, or complaint with the State Executive

Committee, and the said executive committee having

jurisdiction shall fail to promptly meet or having met shall fail to

give with reasonable promptness the full relief required by the

facts and the law the contestant shall have the right forthwith to

file in the circuit court of the county wherein the irregularities are

charged to have occurred, or if more than one county to be

involved then in one (1) of said counties, a sworn copy of his said

protest or complaint, together with a sworn petition, setting forth

with particularity wherein the executive committee has wrongfully

failed to act or to fully and promptly investigate or has wrongfully

denied the relief prayed by said contest, with a prayer for a judicial

review therof. But such petition for a judicial review shall not be

filed unless it bear the certificate of two (2) practicing attorneys

that they and each of them have fully made an independent

investigation into the matters of fact and of law upon which the

protest and petition are based and that after such investigation

they verily believe that the said protest and petition should be

sustained and that the relief therein prayed should be granted, and

the petitioner shall give a cost bond in the sum of Three Hundred

Dollars ($300.00), with two (2) or more sufficient sureties

conditioned to pay all costs in case his petition be dismissed, and

an additional bond may be required, by the judge or chancellor, if

necessary, at any subsequent stage of the proceedings. The filing

of such petition for judicial review in the manner set forth above

shall automatically supersede and suspend the operation and effect

of the order, ruling or judgment of the executive committee

appealed from. (Emphasis supplied.)

38

The Mississippi Supreme Court, after Speaker Gunn sought judicial review, appointed

Judge Forest Johnson to preside over the election contest between Speaker Gunn and Jep

Barbour in Hinds County Circuit Court. After a hearing on the evidence, Judge Forest Johnson

entered his ruling in favor of Speaker Gunn.

Mississippi law is replete with authority that mandates the Supreme Court determine

whether or not jurisdiction exists as a threshold issue, one of the very issues on which Jep

Barbour based his appeal was jurisdiction. Even though the Mississippi Supreme Court is

already mandated to determine the sufficiency of jurisdiction of all cases before it, the parties

specifically raised the issue of jurisdiction before the Court. The Court, through Justice Graves

specifically noted the timing of Speaker Gunns appeal:

Jep Barbour was originally certified as the winner of the

Mississippi House of Representatives District 56 race in the

August 5, 2003 , Republican primary election. His opponent in

the primary, Philip Gunn, filed an election contest on September

8, 2003

890 So.2d at 844 (34 days after the primary election)