Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

15 TH Cent Sleeves

Загружено:

Keerthi Ayeshwarya100%(1)100% нашли этот документ полезным (1 голос)

136 просмотров22 страницыThis document examines depictions of sleeves in 15th century artwork to determine how common the "pin-on sleeve" fashion was. After analyzing 115 images showing 178 women in fitted kirtles, the author finds that 80% depicted long sleeves, 8% showed short sleeves over a smock or long sleeves, 1% had ambiguous sleeves, and 11% appeared to have pin-on sleeves. However, upon closer examination, many of the purported pin-on sleeve depictions were ambiguous or showed women in private/undressed settings, leaving only a few clear examples of pin-on sleeves being worn in public. The author thus questions whether pin-on sleeves were truly as widespread a fashion as often believed.

Исходное описание:

the renaissance dresses

Оригинальное название

15 Th Cent Sleeves

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документThis document examines depictions of sleeves in 15th century artwork to determine how common the "pin-on sleeve" fashion was. After analyzing 115 images showing 178 women in fitted kirtles, the author finds that 80% depicted long sleeves, 8% showed short sleeves over a smock or long sleeves, 1% had ambiguous sleeves, and 11% appeared to have pin-on sleeves. However, upon closer examination, many of the purported pin-on sleeve depictions were ambiguous or showed women in private/undressed settings, leaving only a few clear examples of pin-on sleeves being worn in public. The author thus questions whether pin-on sleeves were truly as widespread a fashion as often believed.

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

100%(1)100% нашли этот документ полезным (1 голос)

136 просмотров22 страницы15 TH Cent Sleeves

Загружено:

Keerthi AyeshwaryaThis document examines depictions of sleeves in 15th century artwork to determine how common the "pin-on sleeve" fashion was. After analyzing 115 images showing 178 women in fitted kirtles, the author finds that 80% depicted long sleeves, 8% showed short sleeves over a smock or long sleeves, 1% had ambiguous sleeves, and 11% appeared to have pin-on sleeves. However, upon closer examination, many of the purported pin-on sleeve depictions were ambiguous or showed women in private/undressed settings, leaving only a few clear examples of pin-on sleeves being worn in public. The author thus questions whether pin-on sleeves were truly as widespread a fashion as often believed.

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 22

Will the Real Fifteenth Century Sleeve Please Stand Up?

Charlotte Johnson (Lady Mathilde Bourette)

mathilde@mathildegirlgenius.com

Atlantia Kingdom Arts and Science Festival

March, 2006

1

Will the Real Fifteenth Century Sleeve Please Stand Up?

Charlotte Johnson (Lady Mathilde Bourette)

Atlantia Kingdom Arts and Science Festival March, 2006

Introduction

In reenacting and SCA circles, the ubiquitous 15

th

century womens casual outfit

consists of a short-sleeved fitted kirtle, with long sleeves pinned on at the shoulders.

While this fashion certainly existed to some extent in 15

th

century Western Europe, was it

as common as many modern-day reenactors and medieval recreationists believe? What

was the most common fashion, as depicted in art? What options are there other than the

pin-on sleeve?

The Evolution of the Overdress

To place the pin-on sleeve in context, we

must look at the garments that accompany

this dress feature. In the mid- to late 14

th

and

early 15

th

centuries, a new, voluminous

garment appeared called a houppelande.

This garment was worn over a fitted under-

dress, or kirtle, which sometimes shows in

various illustrations at the sleeve, neck, or

hem. The sleeves of early houppelandes

were large, and sometimes open, so the

under-sleeves were often visible.

Presumably, one could wear decorative

sleeves over a plain dress, to give the

appearance that the entire under-dress was

of a much richer fabric.

During the mid-15

th

century, the

houppelande evolved into what is commonly

Fig. 1 Mary of Burgundys Book of

Hours; sterreichische

Nationalbibliothek, Vienna; Illumination

on parchment; ca. 146780

2

known as the v-neck, or Burgundian gown, with the neckline becoming wider, the collar

flattening, the sleeves tightening, and the waistline becoming trimmer. By 1470 to 1480,

the sleeves were very snugly fitted (fig. 1). It is likely that it would have been very

uncomfortable to wear this gown over pinned-on sleeves, and unnecessary, as the sleeves

of the under-dress would not be visible at the tight wrists of the over-dress.

The question remains: was a plain kirtle often worn with pin-on sleeves, without the

houppelande, or as the century wore on, v-neck gown? If it was worn at all, was it as

common a style as one might deduce from a general survey of modern reenactor

wardrobes?

A Survey of Sleeve Types

With a perusal of period artwork, it is possible to determine what was common and

realistic fashion in the mid- to late fifteenth century. While the v-neck gown was a much

more popular fashion for almost all social levels, that is not the subject of this paper, and

the data only focuses on the fitted gown, or kirtle. If the sample size of kirtles seems

small, that is due to the more common nature of the v-necked gown in the mid- to late

15

th

century, and not due to a small amount of artwork searched.

Sources

The data is focused on the mid- to late fifteenth century. The earliest well-known pin-

on sleeve example is from ca. 1435, so that is the beginning point

1

. At the end of the

century, there is an overlap of styles between the fitted kirtle, and the more straight-line

early Tudor fashions, including their square necklines. If a particular image was from the

1480s or 90s, it was only included if the kirtle was more in the mid-15

th

century style.

Tudor-style kirtles were not included.

Most of the images come from France or the Low Countries. English art of the 15

th

century is very rare, mostly depicting women in funeral brasses wearing v-neck gowns.

German, Italian, and Spanish fashions are different enough that they would not apply to

this study. The data includes a few German images, however, as there are examples of

pin-on sleeves therein. While there are certainly additional examples of pin-on sleeves

1

Please see fig. 8 for an early example, Rogier van der Weydens Deposition.

3

that were not included, it also stands to reason that there are examples of long and short

sleeves not included as well. The sample size is large enough to give a reasonably

accurate picture of trends in art. For a complete listing of all of the images used, please

see the appendix starting on page 15.

The source pool does not include documentary evidence such as inventories and

wills, due in part to the scope of this project, and the relevance of the information. If

Agnes left two pairs of sleeves to her maid in her will, that would not tell us whether or

not she ever wore the sleeves in public without another gown over them. Documentary

evidence may be able to tell what items were worn and existed, but, in relation to the

question at hand, not necessarily the social context in which they were worn.

Results

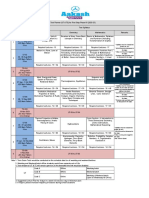

In 115 separate images, 178 women are wearing some form of fitted kirtle. Out of

these, eighty percent (143) of the women are wearing a simple long sleeve, or a long

sleeve visibly over another long sleeve. Eight percent (14) are wearing a short sleeve over

a smock, or short sleeve over long. One percent (2) wear ambiguous sleeves in which

there is no way to guess whether it belongs in the short-over-long, or pin-on category.

Eleven percent (19) clearly wear pin-on sleeves. Fig. 2 illustrates the breakdown.

Distribution of Sleeve Types in Art

Long

Short

Pin on

Ambiguous

Fig. 2

It might seem from this illustration that, while certainly not the most common, the pin-on

sleeve was easily a valid fashion for this time. Lets look closer at the pin-on sleeve

examples, and see how they hold up to scrutiny.

4

The Pin-On Sleeve

An extensive search of period artworks has revealed almost twenty instances of the

pin-on sleeve in 15

th

century artwork. This number would seem adequate to term this a

common fashion; however, there are inherent issues with most of these examples. The

problem sleeves can be grouped into four categories for discussion: ambiguous images,

private space, Mary Magdalene, Saint Barbara. Lastly, there are a few sleeves grouped

into a fifth, non-problem category.

Ambiguous Images

The first category is populated with ambiguous representations of the sleeves. These

dresses appear to have pin-on sleeves, and if the observer wishes to interpret the image as

representing a pin-on sleeve, they may do so. Upon closer examination, there is no

definite way to

determine if the sleeve

is pin-on, or a long-

sleeved dress worn

under a short-sleeved

one. In some cases, the

under-hem is visible

and, if the same color

as the sleeve, it is

likely part of another fitted layer under the visible one.

The detail from Heures de Marguerite dOrleans (fig. 3) is one such example. Some

believe that the women in this illustration are wearing pin-on sleeves. The women

depicted in the margins of this work are wearing various examples of everyday 15

th

century fashion. The woman on the far right is wearing a pink dress, and has blue sleeves.

Are these sleeves pin-on? Notice that her hem is also blue, making it likely the artist was

depicting a woman wearing a pink dress over a blue dress. Of course, it may be a pin-on

sleeve, with a sewn-on hem of the same shade of blue. This uncertainty leaves this image

Fig. 3 Heures de Marguerite dOrlans; Bibliothque

Nationale de France, Paris; Latin 1156 B, fol. 161v; 15

th

cent.

5

somewhat ambiguous, though for the purposes

of the survey, the sleeves were considered short.

The woman in the pink over-dress with red

sleeves likewise has the same configuration of

matching hem and sleeve. A third woman, on

the far left, is wearing a blue dress and has

white sleeves. These could either be pin-on

sleeves, or she may be wearing a short-sleeved

dress worn only over a long-sleeved linen

smock. Again, this image cannot be used as

reliable evidence of pin-on sleeves used in this

context.

The shepherdess in the Rohan Hours (fig. 4)

is also ambiguous, though it seems more likely

that her sleeves are pin-on. It appears that the

sleeves on her pink dress are encased by the dark blue over sleeves. There also appears to

be a white area on the inside of her left arm, which could be explained by a gap between

a short sleeve and the pinned-on sleeve.

When looking at these ambiguous

dresses, one must look for other clues to

help determine whether the sleeve may be

pinned-on. Is there a hem showing in the

same color as the sleeves? Is there any

indication that there might be an under-

dress? Is there any hint of smock showing

between the sleeve and the rest of the

dress? Does the sleeve come up in a point,

indicating that it might be pinned, or is the

color demarcation straight across?

Fig. 4 Grandes heures de Rohan;

Bibliothque Nationale de France,

Paris; Latin 9471, fol. 85.v; ca. mid-

15

th

cent.

Fig. 5 Birth of Mary; Master of the Life of

the Virgin; Alte Pinakothek, Munich; ca.

1460

6

Private Space

In two instances in the sample collection, the pin-on sleeve is shown on women who

are occupied in private space, or in various states of dressing or undress. The Birth of

Mary (fig. 5) depicts two women wearing pin-on sleeves while attending in a birth

chamber. This is one of the few German images

included in the survey, as it is a very clear example of

the pin-on sleeve. The artist may have been using this

particular state of undress to demonstrate that they

were in a private space. The central figure even has

one sleeve off, thus showing that she is not fully

dressed in any sense. While this figure may be used

as evidence that pin-on sleeves existed, this scene

may not constitute evidence that it is appropriate to

wear pin-on sleeves in the public domain.

The next image under study is that of a woman in

the process of abusing her husband with a distaff (fig.

6). This image also has its problems. It shows the

woman putting on a pair of mens braies, or

underwear, indicating that she is the one wearing the

pants in that house, a popular way to depict

male/female role-reversal in the 15

th

century. The fact that she is in the process of

dressing leaves doubt as to whether her pin-on sleeve would be covered by another gown,

or is actually meant to be worn in public.

Mary Magdalene

There are several very famous examples of the pin-on sleeve, most notably those of

Mary Magdalene painted by Rogier van der Weyden. Figs. 7 and 8 are oft-cited

references for this fashion.

Fig. 6 Henpecked Husband;

Israhel van Meckenem; Lehrs

649; ca. 147580

7

Fig. 7 Braque Family Triptych (right

wing); Weyden, Rogier van der; Muse du

Louvre, Paris; ca. 1450

Fig. 8 Deposition; Weyden, Rogier van

der; Museo del Prado, Madrid; ca. 1435

Out of the nineteen pin-on sleeve images found, ten of them are of Mary Magdalene.

Why was she so often depicted dressed in this manner? What was so special about Mary

that might make this garment one of her unofficial symbols? One theory is that Mary, so

distressed and overwrought at the death of Christ, was not fully dressed. Details of her

dress, such as missed eyelet holes with the lace, the pin-on sleeves, the lack of an

overdress, could all have been ways for artists to show her extreme distress. Her clothes

might be acceptable for private wear, but somebody more in their right mind wouldnt

wear such an outfit in public

2

.

2

This idea has been tossed around costuming circles for several years, and was introduced and popularized

by Robin Netherton.

8

Though the Bible does not specifically

mention the connection, popularly Mary

was often known of as the sinner of Luke

7:3650, and was often referred to as a

fallen woman

3

. Perhaps a woman of less

repute might wear the garments of private

space in public.

For whatever the reasons, this

combination of kirtle and pin-on sleeve is

very often shown on Mary Magdalene,

and with other clues, can be used as an

identifying feature in Deposition scenes.

This association with Mary doesnt lend

credibility to the fashion being worn in

public by the average woman, any more than one would expect an average woman to

carry around an urn (one of Marys other well-known iconographic symbols).

Figures 9 and 10 are two more examples. While the

woman in the red dress is certainly Mary Magdalene, figure

10 is questionable. There is another Mary figure in the

Deposition painting that is not shown here, leaving the

woman in blue to be a mystery. Does that mean that a non-

Mary figure is wearing possible pin-on sleeves? Fox points

out in his work on Rogier van der Weyden that the artist of

the Deposition pulled all of his figures directly from van der

Weyden

4

. Even though she is not intended to be Mary

Magdalene, she is still a copy; note the striking similarity

between her and the Magdalene in the Seven Sacraments

altarpiece (fig. 9).

3

Grssinger, p. 34.

4

Fox, p. 129.

Fig. 9 Seven Sacraments (central panel);

Weyden, Rogier van der; Koninklijk

Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp;

145550

Fig. 10 Deposition;

Master of the Legend of

St. Catherine; Wallraf-

Richartz-Museum,

Cologne; ca. 14701480

9

Saint Barbara

Saint Barbara (figs. 11 and 12) was another popular female saint during the Middle

Ages, often depicted carrying the tower in which she was imprisoned as her identifying

symbol. In the early Christian era, the legendary Barbara was locked in a tower by her

father, to prevent her from seeing men, or to prevent her from learning Christian doctrine,

depending on the legend. She converted to Christianity, and her father had her beheaded

5

.

For most of her life, Barbara lived alone in that tower, never entering the public sphere.

Considering that we have other examples of the sleeves in a private space, could the artist

have been giving a nod to her captivity?

Fig. 11 Memling, Hans; The Donne

Triptych; National Gallery, London; ca.

1475

Fig. 12 Memling, Hans; Triptych of the

Family Moreel; Groeninge Museum,

Bruges; ca. 1484

5

Grssinger, p. 33.

10

Non-Problem Sleeves

There are a few unambiguous images left of pin-on sleeves that dont have any

apparent problems. For the purposes of the sleeve survey, the shepherdess in the Rohan

Hours (fig. 4) is considered a pin-on sleeve.

Fig. 13 Lidet, Layset,

Gerard and Bertha Find

Sustenance at a Hermitage,

Histoire de Charles Martel;

J . Paul Getty Museum, Los

Angeles; ca. 1460s

Fig. 14 Les douze dames de

rhtorique; Montferrant;

Bibliothque Nationale, Paris; MS.

Fr. 1174, f. 29r; 15th c.

Fig. 15 Bibliothque

Nationale, Paris; MS.

Arsenal 5073, f. 336;

4th quarter, 15th c.

Figs. 1315 show women who are not saints, and who are not apparently in a private

space, wearing a pin-on sleeve. Its possible that there is some reason for it, or it could

have been a rare fashion. Fig. 15 does seem to be some sort of allegorical image, as one

of the Twelve Women of Rhetoric, though without more background, she is not

inherently a problem image. As an aside, note that they are all wearing a similar

headdress. It may also be noted, however, that the shepherdess (fig. 4) and the women in

figs. 14 and 15 are laboring and may be in some form of undress, as men of the period in

11

similar functions are often depicted wearing only shirts or doublets, without the proper

gown, which is worn where they are considered fully-dressed.

A Survey of Sleeve Types Redux

What happens to the sleeve breakdown when images depicting Mary Magdalene,

Saint Barbara, and women in private space are removed from consideration? When

looking closer at the images, many pin-on sleeves fall in the categories described above.

As shown in fig. 16, over half (10) of the images are of Mary Magdalene. Three of the

women depicted are in a private space, or are in the process of dressing. There are two

images of St. Barbara, which leaves four non-problem sleeve images.

If you remove the problem sleeves from the equation, the big picture changes. As

shown in fig. 17, eighty-eight percent of the sleeves are long, nine percent are short, still

only one percent are ambiguous, but now only two percent of the sleeves are pin-on.

Distribution of Pin on Sleeve Wearers

Magdalene

Private Space

Barbara

Other

Fig. 16

12

Even without taking the problem sleeves into

consideration there are many more depictions of a

simple long sleeve. When removing the problem

sleeves from the mix, the pin-on sleeve becomes a very

small subset of the total. In either case, it appears that

the norm is a plain long sleeve.

Long Sleeves and Layers in the 15

th

Century

What other options are there in sleeve styles? Long

sleeve or short, there are plenty of ways to wear sleeves

aside from pin-on. Take into consideration that short

sleeves are also not as common as long, and its

possible to achieve a wide mix of styles within a

particular group of women.

Fig. 18 shows a simple long sleeve, worn over

another long sleeve. The black barely visible at her

cuffs is the same black showing below her hem.

Presumably, she is wearing a long-sleeved dress over another long-sleeved dress.

Distribution of Sleeve Types without Problem

Subjects

Long

Short

Pin on

Ambiguous

Fig. 17

Fig. 18 Last Judgment and the

Wise and Foolish Virgins;

Staatliche Museen, Berlin;

1450s and ca. 1480

13

Fig. 19 shows an image like many in mid- to

late 15

th

century art. Viviane is wearing a plain

long sleeve, and it is unclear whether she is

wearing anything else under that layer. She could

be wearing another dress under, or it could be a

single layer. A single visible layer does seem to

be the most common depiction of this time period.

In the St. John Altarpiece, another woman

wears a long sleeve over another long sleeve. The

under sleeves are buttoned tight at the wrist, with

at least four or five buttons. The long sleeves of

the over-dress are not particularly tight, as she is

able to push them up to her elbows.

Though short sleeves dont seem

nearly as common as long, they certainly

existed and were about as common as

the pin-on sleeve, as shown by the

survey above. In fig. 3, it appears that

several of the women are wearing a short

sleeve over a long sleeve, as the sleeve

matches the hem of the under dress. Fig.

21 shows a woman who is simply

wearing a short sleeve dress over a

smock. Often, like the pin-on sleeve,

short-sleeved dresses seem also to be worn in private space, or casual circumstances.

Fig. 19 vrard dEspiniques,

Lancelot Enlev Par Viviane;

Bibliothque Nationale, Paris; MS

Franais 113, fol. 156v; mid-to late

15

th

cent.

Fig. 20 Weyden, Rogier van der; St John

Altarpiece (left panel); Staatliche Museen,

Berlin; 145560

14

Summary

Whether one considers sleeves worn by Mary

Magdalene, Saint Barbara, or in private space to be

valid or not, certainly a long-sleeved dress is much

more common than a pin-on sleeve outfit. The ratio is

anywhere from 8:1, to 44:1, depending on which

arguments are accepted. While the pin-on sleeve may

have existed, it doesnt seem to have been normal

public attire for most women. Even in the few examples

we do have of a normal woman wearing it in a non-

private space, she is generally undertaking some sort of

work or heavy labor. Wearing it may be akin to a 24

th

century person reenacting the late 20

th

century by

wearing a bustier to an office scenario.

Fig. 21 Memling, Hans;

Advent and Triumph of Christ;

Alte Pinakothek, Munich;

1480

15

Appendix:

These images are listed by source. For more details on the sources, please see the

bibliography below. All images from the Bibliothque Nationale de France are listed in

one subsection, though are broken out in the bibliography for ease of reference. The

website <http://gallica.bnf.fr>can be difficult to navigate for a non-French speaker.

Bibliothque Nationale

Mose et Dieu. Mose frappant le rocher; Antiquits judaques; MS Fr 11, Fol. 64

Chtiment de Cor; Antiquits judaques; MS Fr 11, Fol. 90

Rahab et les espions de Josu. Prise de Jricho. Samson et le lion, Antiquits

judaques; MS Fr 12, Fol. 111

Onction de Sal. David dcapitant Goliath, Antiquits judaques; MS Fr 12, Fol.

135v

Philosophe abus par un dmon, De civitate Dei; MS Fr 27, Fol. 259v

Enlvement des Sabines, De civitate Dei; MS Fr 27, Fol. 28

Conception d'Alexandre. Naissance d'Alexandre, Histoire d'Alexandre le Grand; MS

Fr 47, Fol. 16

Saturne l'oracle de Delphes. Naissance de Jupiter, Histoires de Troyes; MS Fr 59,

Fol. 1

Confession de la mre de Merlin, Histoire de Merlin; MS Fr 91, Fol. 1

Mort du fils de Meliadus, Tristan de Lonois; MS Fr 102, Fol. 26v

Mariage de Pellias et d'Arcade, Lancelot du Lac; MS Fr 112, Fol. 28v

Gahari recevant le chapel, Lancelot du Lac; MS Fr 112, Fol. 45

Guenivre la Roche as Saisnes, Lancelot du Lac; MS Fr 112, Fol. 152v

Tristan et Iseut buvant le philtre, Lancelot du Lac; MS Fr 112, Fol. 239

Naissance de Lancelot, Histoire du saint Graal; MS Fr 113, Fol. 1

Ban de Benoc, Bohort et leurs familles, Histoire du saint Graal; MS Fr 113, Fol.

150v

Mort de Ban de Benoc, Histoire du saint Graal; MS Fr 113, Fol. 154v

Lancelot enlev par Viviane, Lancelot du Lac; MS Fr 113, Fol. 156v

Lancelot embrassant Guenivre, Lancelot du Lac; MS Fr 114, Fol. 244v

Combat de Gauvain et de Gloadain, Lancelot du Lac; MS Fr 114, Fol. 280v

Lancelot Soulevant Drian, Lancelot du Lac; MS Fr 114, Fol. 329

Gauvain prisonnier de Caradoc le Grant, Lancelot du Lac; MS Fr 114, Fol. 336v

Gauvain et la demoiselle, Lancelot du Lac; MS Fr 115, Fol. 361v

16

Guenivre confrontant les anneaux, Lancelot du Lac; MS Fr 115, Fol. 370v

Galinde devant sa nice, Lancelot du Lac; MS Fr 115, Fol. 386v

Lancelot et Griffon del Mal Pas, Lancelot du Lac; MS Fr 115, Fol. 409

Lancelot et les enchanteresses, Lancelot du Lac; MS Fr 115, Fol. 456v

Lancelot la carole magique, Lancelot du Lac; MS Fr 115, Fol. 476

Guenivre bannissant Lancelot, Lancelot du Lac; MS Fr 115, Fol. 568v

Perceval prsent son frre, Qute du saint Graal; MS Fr 116, Fol. 593v

Mort de Gaharis, Qute du saint Graal; MS Fr 116, Fol. 692v

Naissance de Jupiter, ; MS Fr 137, Fol. 3v

Tirsias prdisant la fin de Narcisse, Metamorphoseon libri XV; MS Fr 137, Fol. 35

Minyades mprisant Bacchus, Metamorphoseon libri XV; MS Fr 137, Fol. 42v

Mde rajeunissant Aeson, Metamorphoseon libri XV; MS Fr 137, Fol. 91

Philomle, Procn et Tre, Metamorphoseon libri XV; MS Fr 137, Fol. 80v

Mtamorphose des bergers lyciens, Metamorphoseon libri XV; MS Fr 137, Fol. 78v

Arachn dfiant Minerve. Mtamorphose d'Arachn, Metamorphoseon libri XV; MS

Fr 137, Fol. 73v

Enlvement de Proserpine, Metamorphoseon libri XV; MS Fr 137, Fol. 68v

Perse dlivrant Andromde, Metamorphoseon libri XV; MS Fr 137, Fol. 61

Camille

p. 93; A castle of unbridled female desire, The Housebook, fols 23v-24r; Frstlich

Leinningensche Sammlungen Heimatismuseum; ca. 1475-85

Campbell

p. 39; Bouts, Dirk; The Entombment; London, National Gallery; ca. 1450-55

p. 306; Marmion, Simon; Scenes from the Life of Stain Bertin; Berlin, Staatliche

Museen; ca. 1450s

p. 377; Memling, Hans; The Virgin and Child with Saints and Donors (The Donne

Triptych); London, National Gallery; ca. 1478

p. 421; Master of the Prado Redemption; Saint Helena discovering the True Cross;

Madrid, private collection; mid-fifteenth century

Davenport

p. 309; Tapestry: Hawking; Hardwick Hall, Mansfield; ca. 1445

17

p. 311; Wauquelin, J ean; Chronicles of Hainault; Bibliothque Royale, Brussels; MS.

9242-4; ca. 1447

p. 316; Wauquelin, J ean; Ystoire de Helayne; Bibliothque Royale, Brussels; MS.

9967; ca. 1448

p. 327; Milot, J ean; Epitre dOthea; Bibliothque Royale, Brussels; MS. 9392; ca.

1461

p. 331; Froissart; Chronicles of England, France, and Spain; Bibliothque Nationale,

Paris; MS. Fr. 2644; mid-15th century

p. 339; Hours of Anne de Beaujou; Morgan Library; MS 667; ca. 1480

Fox

Cover; Heures de La Duchesse de Bourgogne, Harvesting Fruit; Muse Cond,

Chantilly; ca. 1450

J anuary 1; Livre des symples medichines, autrement dit Arboriste; Bibliothque

Nationale, Paris; MS. Fr. 9136, f. 344; 4th quarter, 15th c.

J anuary 19; Livre des proprits des choses; Bibliothque Nationale, Paris; MS. Fr.

9140, f. 107; 4th quarter, 15th c.

May 13 detail; Bibliothque Nationale, Paris; MS. Arsenal 5073, f. 336; 4th quarter,

15th c.

J une 13; Histoires des nobles princes de Hainaut; J acques de Guise; Bibliothque

Municipale, Boulogne/s/Mer; MS. 149, tome 3, f. 119; second half, 15th c.

J une 19; Les douze dames de rhtorique; Montferrant; Bibliothque Nationale, Paris;

MS. Fr. 1174, f. 29r; 15th c.

August 7; Tractabus de herbis; Dioscorides; Miblioteca Estense, Modena; MS. Lat.

993, f. 142r; 15th c.

September 13; Quart volume de histoire scolastique; J . du Ries; British Library,

London; MS. Royal 15 Di, f. 18; 1470

Grssinger

p. 32; Moser, Lucas: Altarpiece of St Magdalene; Tiefenbronn, Parish Church; ca.

1432

p. 116; Henpecked Husband, Israhel van Meckenem, engraving, ca. 1475-80, Lehrs

649

Kemperdick

p. 13; Deposition; Rogier van der Weyden; Prado, Madrid; ca. 1435-1440

18

p. 20; Nativity Triptych; Anonymous; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; ca.

1460-70

p. 26; Trajan and Herkinbald Tapestry; Anonymous; Bernisches Historiches

Museum, Berne; before 1461

p. 45; Abegg Triptych; Workshop of Rogier van der Weyden; Abegg-Stiftung,

Riggisberg near Berne; ca. 1445

p. 47; Seven Sacraments Altarpiece; Rogier van der Weyden; Koninklijk Museum

voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp; ca. 1445-50

p. 51; Crucifixion; Workshop or circle of Rogier van der Weyden; Gemldegalerie,

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin; ca. 1440-50

p. 70; Last Judgment, and the Wise and Foolish Virgins; Anonymous;

Gemldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin; ca. 1450-60

p. 74; Braque Triptych; Rogier van der Weyden; Louvre, Paris; ca. 1450

p. 81; Columba Altarpiece; Rogier van der Weyden; Staatsgemldesammlunger,

Munich; ca. 1455

p. 93; Deposition; Anonymous; Staatsgemldesammlunger, Munich; ca. 1460

p. 97; Hunting Stags and Herons; Victoria and Albert Museum, London; ca. 1440

p. 113; St. John Altarpiece; Rogier van der Weyden; Gemldegalerie, Staatliche

Museen zu Berlin; ca. 1455-60

p. 128; Deposition; Master of the Legend of St. Catherine; Wallraf-Richartz-Museum,

Cologne; ca. 1470-80

Marks and Williamson

p. 291; The Buxton Achievement; Strangers Hall, Norwich; ca. 1470

Pierce

p. 103; St. Agatha, fromThe Hours of Catherine of Cleves; Master of Catherine of

Cleves; ca. 1440

p. 125; Anger; Robinet Testard; ca. 1475

p. 126; Avarice; Robinet Testard; ca. 1475

p. 127; Gluttony; Robinet Testard; ca. 1475

p. 128; Sloth; Robinet Testard; ca. 1475

p. 128; Lust; Robinet Testard; ca. 1475

p. 181; City Youths Dancing from The Hours of Anne de France; J ean Colombe; ca.

1473

19

p. 193; Livre des prouffis champestres et ruraux; Master of Margaret of York; ca.

1470

Scott

p. 87; The Story of Patient Griselda, Master of Mansel, post 1451

Sinclair

Plate 2; The Adoration of the Magi

Plate 7; The Visitation

Plate 8; The Nativity

Plate 16; The Road to Calvary

Plate 19; The Piet

Plate 29; The Birth of Saint John the Baptist

Plate 39; St. Veranus Curing the Insane

Plate 41; The Magdalene Wiping Christ's Feet

Plate 44; St. Anne and the Three Marys

Tanis

p. 77; Book of Hours for Rouen Use, The Visitation; Workshop of the Master of the

chevinage de Rouen; The Library Company of Philadelphia; MS 5 fol. 39v; ca.

1470

p. 79; Book of Hours for Rome Use, Nativity; Master of the Collins Hours;

Philadelphia Museum of Art; fols. 73v-74; ca. 1445-50

p. 84; Leaf From a Book of Hours, Annunciation to the Shepherds; Master of

Guillaume Lambert; Free Library of Philadelphia; ca. 1485

p. 107; Book of Hours for Sarum Use, Verionica with Her Veil; miniature inside

clasp; Free Library of Philadelphia; ca. 1460-70

p. 138; Raising of Lazarus; Free Library of Philadelphia; ca. 1490-1500

p. 162; Leaf from an Antiphonary; Historiated Initial H with the Nativity; Free

Library of Philadelphia; ca. 1440

p. 211; Idleness and the Dreamer-Lover in the Garden of Pleasure, Roman de la Rose;

Philadelphia Museum of Art; fol. 143; ca. 1440-1480

p. 214; Venus Aiming her Arrow at Fear and Shame, Roman de la Rose; Philadelphia

Museum of Art; fol. 143; ca. 1440-1480

20

Bibliography:

Augustine, Saint. De civitate Dei. Translated by Raoul de Presles. Bibliothque Nationale

de France, Franais 27, <http://gallica.bnf.fr/scripts/Notice.php?O=08100056>; (1

J anuary 2006).

Backhouse, J anet. The Illuminated Page: Ten Centuries of Manuscript Painting.

Bibliothque National, <http://gallica.bnf.fr/>(1 J anuary 2006)

Camille, Michael. The Medieval Art of Love. London: Harry N. Abrams, 1998.

Campbell, Lorne. The Fifteenth Century Netherlandish Paintings. London: National

Gallery Company Limited, 1998.

Davenport, Milla. The Book of Costume; New York: Crown Publishers, 1976

Flavius, J osphe. Antiquits judaques (traduction anonyme). Bibliothque Nationale de

France, Franais 11, <http://gallica.bnf.fr/scripts/Notice.php?O=08100015>; (1 J anuary

2006).

Flavius, J osphe. Antiquits judaques (traduction anonyme). Bibliothque Nationale de

France, Franais 12, <http://gallica.bnf.fr/scripts/Notice.php?O=08100016>; (1 J anuary

2006).

Fouquet, J ean. The Hours of Etienne Chevalier. Translated by Marianne Sinclair. New

York: George Braziller, 1971.

Fox, Sally, ed. The Medieval Woman. Little, Brown and Company, 1985.

Grssinger, Christa. Picturing Women in Late Medieval and Renaissance Art.

Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997.

Kemperdick, Stephan. Masters of Netherlandish Art: Rogier van der Weyden. Cologne:

Knemann Verlagsgesellschaft, 1999.

Landsberg, Sylvia. The Medieval Garden. London: British Museum Press.

Lefvre, Raoul. Histoires de Troyes. Bibliothque Nationale de France, Franais 59,

<http://gallica.bnf.fr/scripts/Notice.php?O=08100062>; (1 J anuary 2006).

Marks, Richard and Williamson, Paul, eds. Gothic Art for England, 1400-1547. London:

Victoria and Albert Museum, 2003.

Ovid. Metamorphoseon libri XV. Bibliothque Nationale de France, Franais 137,

<http://gallica.bnf.fr/scripts/Notice.php?O=08100128>; (1 J anuary 2006).

21

Pierce, J r., Charles. Illuminated Manuscripts: Treasures of the Pierpont Morgan Library,

New York. New York, Abbeville Press, 1998.

Quinte-Curce. Histoire d'Alexandre le Grand. Bibliothque Nationale de France, Franais

47, <http://gallica.bnf.fr/scripts/Notice.php?O=08100011>; (1 J anuary 2006).

Scott, Margaret. A Visual History of Costume: The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries.

London: B. T. Batsford, 1986.

Tanis, J ames. Leaves of Gold: Manuscript Illumination from Philadelphia Collections.

Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2001.

Unknown. Histoire de Merlin. Bibliothque Nationale de France, Franais 91,

<http://gallica.bnf.fr/scripts/Notice.php?O=08100072>; (1 J anuary 2006).

Unknown. Histoire du saint Graal. Bibliothque Nationale de France, Franais 113,

<http://gallica.bnf.fr/scripts/Notice.php?O=08100101>; (1 J anuary 2006).

Unknown. Lancelot du Lac. Bibliothque Nationale de France, Franais 112,

<http://gallica.bnf.fr/scripts/Notice.php?O=08100001>; (1 J anuary 2006).

Unknown. Tristan de Lonois. Bibliothque Nationale de France, Franais 102,

<http://gallica.bnf.fr/scripts/Notice.php?O=08100040>; (1 J anuary 2006).

Unknown. Lancelot du Lac. Bibliothque Nationale de France, Franais 114,

<http://gallica.bnf.fr/scripts/Notice.php?O=08100102>; (1 J anuary 2006).

Unknown. Lancelot du Lac. Bibliothque Nationale de France, Franais 115,

<http://gallica.bnf.fr/scripts/Notice.php?O=08100103>; (1 J anuary 2006).

Unknown. Qute du saint Graal. Bibliothque Nationale de France, Franais 116,

<http://gallica.bnf.fr/scripts/Notice.php?O=08100104>; (1 J anuary 2006).

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Melanie Cozad and Kim Barker for pointing me in the direction of some

useful images.

Thank you to Brent Hanner for providing a large repository of high quality images of 15

th

century art.

Thank you to my editorial readers who provided me with useful comments and

constructive feedback.

Вам также может понравиться

- Medieval - Garments (Libro de Patrones de Costura Costura Nordico) PDFДокумент144 страницыMedieval - Garments (Libro de Patrones de Costura Costura Nordico) PDFStephie Pay de Mora95% (20)

- Men's 1630s DoubletДокумент13 страницMen's 1630s DoubletDean Willis100% (1)

- ReconstructingTheFrenchHood 06-2009Документ27 страницReconstructingTheFrenchHood 06-2009qwertymoonОценок пока нет

- Fashion Accessories - Since 1500 (History Arts)Документ168 страницFashion Accessories - Since 1500 (History Arts)Mariana Meirelles100% (3)

- Eighteenth-Century French Fashion Plates in Full Color: 64 Engravings from the "Galerie des Modes," 1778-1787От EverandEighteenth-Century French Fashion Plates in Full Color: 64 Engravings from the "Galerie des Modes," 1778-1787Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5)

- English Women's Clothing in the Nineteenth Century: A Comprehensive Guide with 1,117 IllustrationsОт EverandEnglish Women's Clothing in the Nineteenth Century: A Comprehensive Guide with 1,117 IllustrationsРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (2)

- Overview of Ottoman Clothing in SCA PeriodДокумент16 страницOverview of Ottoman Clothing in SCA PeriodWoodrow "asim" Jarvis Hill100% (15)

- 13th Century BraiesДокумент10 страниц13th Century Braiessarahmichelef100% (3)

- The Italian CamiciaДокумент12 страницThe Italian CamiciaFlorenciaОценок пока нет

- Viking Apron DressДокумент16 страницViking Apron DressSociedade Histórica Destherrense100% (6)

- 14th Century GarmentsДокумент25 страниц14th Century GarmentsAdriana ParraОценок пока нет

- 13th Century Rapier Armor (June 2009)Документ6 страниц13th Century Rapier Armor (June 2009)sarahmichelef100% (1)

- The Cut of Woman's DressДокумент39 страницThe Cut of Woman's DressShuyi Fu60% (10)

- (Dan Stone) The Historiography of The HolocaustДокумент586 страниц(Dan Stone) The Historiography of The HolocaustPop Catalin100% (1)

- Gandhi Was A British Agent and Brought From SA by British To Sabotage IndiaДокумент6 страницGandhi Was A British Agent and Brought From SA by British To Sabotage Indiakushalmehra100% (2)

- Apache Hive Essentials 2nd PDFДокумент204 страницыApache Hive Essentials 2nd PDFketanmehta4u0% (1)

- 14thc Martial Surcottes in England and FranceДокумент28 страниц14thc Martial Surcottes in England and FranceKatja Kali Zaccheo100% (1)

- Chapter 5 The Early Middle Ages Vocab TermsДокумент23 страницыChapter 5 The Early Middle Ages Vocab Termsapi-513623665Оценок пока нет

- Sideless Surcoat Web PDFДокумент12 страницSideless Surcoat Web PDFsrdjan_stanic_1Оценок пока нет

- Presented by Abhijit Banik Textile DesignДокумент37 страницPresented by Abhijit Banik Textile DesignAbhijit Banik100% (1)

- Burg Und Ian CostumeДокумент19 страницBurg Und Ian CostumeGeorgy Borgy100% (1)

- The Eighteenth Century PDFДокумент65 страницThe Eighteenth Century PDFAlexei Ada100% (2)

- Men's and Women's 1600s Shirts and ShiftsДокумент13 страницMen's and Women's 1600s Shirts and ShiftsDean Willis100% (4)

- Men's and Women's 17thc Collars and CuffsДокумент14 страницMen's and Women's 17thc Collars and CuffsDean Willis100% (1)

- Historical Costumes of England - From the Eleventh to the Twentieth CenturyОт EverandHistorical Costumes of England - From the Eleventh to the Twentieth CenturyОценок пока нет

- History Drawers On: The Evolution of Women's KnickersОт EverandHistory Drawers On: The Evolution of Women's KnickersРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1)

- Illustrated Handbook of Western European Costume: Thirteenth to Mid-Nineteenth CenturyОт EverandIllustrated Handbook of Western European Costume: Thirteenth to Mid-Nineteenth CenturyОценок пока нет

- The "Keystone" Jacket and Dress Cutter: An 1895 Guide to Women's TailoringОт EverandThe "Keystone" Jacket and Dress Cutter: An 1895 Guide to Women's TailoringРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (4)

- Red C. 1380 Western European Fitted Gown, Lined in Blue LinenДокумент10 страницRed C. 1380 Western European Fitted Gown, Lined in Blue LinenKeerthi AyeshwaryaОценок пока нет

- Dress in ByzantiumДокумент7 страницDress in ByzantiumOana StroeОценок пока нет

- Rus Male CostumeДокумент12 страницRus Male CostumeFrancisco Agenore Cerda Morello100% (1)

- Catlin's Riding TunicДокумент5 страницCatlin's Riding Tunicsarahmichelef100% (2)

- Merovingian DressДокумент4 страницыMerovingian Dressletzian100% (2)

- Women's Clothing EvolutionДокумент165 страницWomen's Clothing EvolutionLibby Brooks100% (5)

- Siglo XVIII Proporciones VestidosДокумент5 страницSiglo XVIII Proporciones VestidosCristal CarolinaОценок пока нет

- Ropa Medieval Siglo XVДокумент20 страницRopa Medieval Siglo XVpatata76Оценок пока нет

- Serpentine Braids or Straight As A Scabbard: Women's Court Hairdressing In12th Century EuropeДокумент8 страницSerpentine Braids or Straight As A Scabbard: Women's Court Hairdressing In12th Century EuropeB Maura TownsendОценок пока нет

- 15c Mens Italian GarmentsДокумент12 страниц15c Mens Italian GarmentsGeorge SiegОценок пока нет

- Clothing in Ancient RomeДокумент6 страницClothing in Ancient Romeana parriegoОценок пока нет

- The Textiles of The Oseberg ShipДокумент25 страницThe Textiles of The Oseberg ShipHalfdan Fjallarsson100% (5)

- Green Linen CyclasДокумент7 страницGreen Linen Cyclassarahmichelef100% (2)

- A Cyclopaedia of Costume or Dictionary of DressДокумент528 страницA Cyclopaedia of Costume or Dictionary of Dressuniek1977100% (1)

- 14th Century Northern Italian Womens Clothing ClassДокумент6 страниц14th Century Northern Italian Womens Clothing ClassAndrea HusztiОценок пока нет

- How To Pleat A Shirt in The 15th Century PDFДокумент13 страницHow To Pleat A Shirt in The 15th Century PDFAndrea HusztiОценок пока нет

- Period Ottoman Coats SurveyДокумент3 страницыPeriod Ottoman Coats SurveyWoodrow "asim" Jarvis Hill100% (2)

- The Well-Dress'd PeasantДокумент68 страницThe Well-Dress'd PeasantDrea Leed80% (5)

- Danish SerkДокумент12 страницDanish SerkMackenzie100% (1)

- RH106 Notes LetterДокумент8 страницRH106 Notes LetterDean Willis100% (1)

- Medieval and Early Modern Silk Textiles 1 PDFДокумент64 страницыMedieval and Early Modern Silk Textiles 1 PDFAndrea HusztiОценок пока нет

- Daisies Christmas Wreaths: History of Floral Design in Renaissance Period (1400-1600 A.D.)Документ1 страницаDaisies Christmas Wreaths: History of Floral Design in Renaissance Period (1400-1600 A.D.)Keerthi AyeshwaryaОценок пока нет

- 14th Century Woman's Hood: MaterialsДокумент4 страницы14th Century Woman's Hood: MaterialsKeerthi AyeshwaryaОценок пока нет

- Red C. 1380 Western European Fitted Gown, Lined in Blue LinenДокумент10 страницRed C. 1380 Western European Fitted Gown, Lined in Blue LinenKeerthi AyeshwaryaОценок пока нет

- History of Floral Design in Renaissance Period (1400-1600 A.D.)Документ1 страницаHistory of Floral Design in Renaissance Period (1400-1600 A.D.)Keerthi AyeshwaryaОценок пока нет

- The Color PaletteДокумент8 страницThe Color PaletteKeerthi AyeshwaryaОценок пока нет

- Protected Area Network in IndiaДокумент99 страницProtected Area Network in IndiaKeerthi AyeshwaryaОценок пока нет

- Medieval ClothingДокумент12 страницMedieval ClothingKeerthi Ayeshwarya100% (1)

- Arch Thesis InventoryДокумент127 страницArch Thesis InventoryKeerthi AyeshwaryaОценок пока нет

- Vastu PDFДокумент2 страницыVastu PDFKeerthi AyeshwaryaОценок пока нет

- NBC Chapter 24Документ1 страницаNBC Chapter 24Keerthi AyeshwaryaОценок пока нет

- Tower Suite Extraordinaire: 4 Bedrooms, 4 Full Baths Powder RoomДокумент1 страницаTower Suite Extraordinaire: 4 Bedrooms, 4 Full Baths Powder RoomKeerthi AyeshwaryaОценок пока нет

- Chapter 27Документ4 страницыChapter 27Keerthi AyeshwaryaОценок пока нет

- Shielded Metal Arc Welding Summative TestДокумент4 страницыShielded Metal Arc Welding Summative TestFelix MilanОценок пока нет

- GN No. 444 24 June 2022 The Public Service Regulations, 2022Документ87 страницGN No. 444 24 June 2022 The Public Service Regulations, 2022Miriam B BennieОценок пока нет

- Quarter 3 Week 6Документ4 страницыQuarter 3 Week 6Ivy Joy San PedroОценок пока нет

- ObliCon Digests PDFДокумент48 страницObliCon Digests PDFvictoria pepitoОценок пока нет

- Progressivism Sweeps The NationДокумент4 страницыProgressivism Sweeps The NationZach WedelОценок пока нет

- Creative Nonfiction 2 For Humss 12 Creative Nonfiction 2 For Humss 12Документ55 страницCreative Nonfiction 2 For Humss 12 Creative Nonfiction 2 For Humss 12QUINTOS, JOVINCE U. G-12 HUMSS A GROUP 8Оценок пока нет

- RubricsДокумент1 страницаRubricsBeaMaeAntoniОценок пока нет

- Tamil and BrahminsДокумент95 страницTamil and BrahminsRavi Vararo100% (1)

- Nastran 2012 Superelements UgДокумент974 страницыNastran 2012 Superelements Ugds_srinivasОценок пока нет

- The Recipe For Oleander Sou1Документ4 страницыThe Recipe For Oleander Sou1Anthony SullivanОценок пока нет

- Lewin's Change ManagementДокумент5 страницLewin's Change ManagementutsavОценок пока нет

- RR 10-76Документ4 страницыRR 10-76cheska_abigail950Оценок пока нет

- Musculoskeletan Problems in Soccer PlayersДокумент5 страницMusculoskeletan Problems in Soccer PlayersAlexandru ChivaranОценок пока нет

- SHS11Q4DLP 21st CentFinalДокумент33 страницыSHS11Q4DLP 21st CentFinalNOEMI DE CASTROОценок пока нет

- Alexander Blok - 'The King in The Square', Slavonic and East European Review, 12 (36), 1934Документ25 страницAlexander Blok - 'The King in The Square', Slavonic and East European Review, 12 (36), 1934scott brodieОценок пока нет

- GearsДокумент14 страницGearsZulhilmi Chik TakОценок пока нет

- The Preparedness of The Data Center College of The Philippines To The Flexible Learning Amidst Covid-19 PandemicДокумент16 страницThe Preparedness of The Data Center College of The Philippines To The Flexible Learning Amidst Covid-19 PandemicInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyОценок пока нет

- Sodium Borate: What Is Boron?Документ2 страницыSodium Borate: What Is Boron?Gary WhiteОценок пока нет

- Endzone Trappers Lesson PlanДокумент2 страницыEndzone Trappers Lesson Planapi-484665679Оценок пока нет

- Information Theory Entropy Relative EntropyДокумент60 страницInformation Theory Entropy Relative EntropyJamesОценок пока нет

- Bakhtin's Chronotope On The RoadДокумент17 страницBakhtin's Chronotope On The RoadLeandro OliveiraОценок пока нет

- UT & TE Planner - AY 2023-24 - Phase-01Документ1 страницаUT & TE Planner - AY 2023-24 - Phase-01Atharv KumarОценок пока нет

- Nahs Syllabus Comparative ReligionsДокумент4 страницыNahs Syllabus Comparative Religionsapi-279748131Оценок пока нет

- Analog Electronic CircuitsДокумент2 страницыAnalog Electronic CircuitsFaisal Shahzad KhattakОценок пока нет

- Predictive Tools For AccuracyДокумент19 страницPredictive Tools For AccuracyVinod Kumar Choudhry93% (15)

- Percy Bysshe ShelleyДокумент20 страницPercy Bysshe Shelleynishat_haider_2100% (1)

- Edc Quiz 2Документ2 страницыEdc Quiz 2Tilottama DeoreОценок пока нет