Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

First Do No Harm: A Real Need To Deprescribe in Older Patients

Загружено:

caffyw0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

114 просмотров3 страницыDeliberate yet judicious deprescribing has considerable potential to relieve unnecessary medication-related suffering and disability in vulnerable older populations. A report by the Medical Journal of Australia.

Оригинальное название

First do no harm: a real need to deprescribe in older patients

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документDeliberate yet judicious deprescribing has considerable potential to relieve unnecessary medication-related suffering and disability in vulnerable older populations. A report by the Medical Journal of Australia.

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

114 просмотров3 страницыFirst Do No Harm: A Real Need To Deprescribe in Older Patients

Загружено:

caffywDeliberate yet judicious deprescribing has considerable potential to relieve unnecessary medication-related suffering and disability in vulnerable older populations. A report by the Medical Journal of Australia.

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 3

Clinical focus

1 MJA 201 (7) 6 October 2014

Clinical focus

Ian A Scott

FRACP, MHA, MEd

Director of Internal Medicine

and Clinical Epidemiology

1

Kristen Anderson

BPharm

PhD Scholar,

2

and

Advanced Primary Care

Pharmacist Fellow

3

Christopher R Freeman

BPharm, PhD, BCACP

Director of Pharmacy

3

Danielle A Stowasser

PhD, BPharm,

PGDipClinHospPharm

Associate Professor of

Pharmacy

4

1 Princess Alexandra Hospital,

Brisbane, QLD.

2 Centre of Research

Excellence in Quality

and Safety in Integrated

Primary/Secondary Care,

University of Queensland,

Brisbane, QLD.

3 CHARMING Institute,

Brisbane, QLD.

4 University of Queensland,

Brisbane, QLD.

ian.scott@

health.qld.gov.au

doi: 10.5694/mja14.00146

Summary

Inappropriate polypharmacy in older patients imposes

a significant burden of decreased physical functioning,

increased risk of falls, delirium and other geriatric

syndromes, hospital admissions and death.

The single most important predictor of inappropriate

prescribing and risk of adverse drug events in older

patients is the number of prescribed medications.

Deprescribing is the process of tapering or stopping

drugs, with the goal of minimising polypharmacy and

improving outcomes.

Barriers to deprescribing include underappreciation

of the scale of polypharmacy-related harm by both

patients and prescribers; multiple incentives to

overprescribe; a narrow focus on lists of potentially

inappropriate medications; reluctance of prescribers

and patients to discontinue medication for fear

of unfavourable sequelae; and uncertainty about

effectiveness of strategies to reduce polypharmacy.

Ways of countering such barriers comprise reframing

the issue to one of highest quality patient-centred

care; openly discussing benefitharm trade-offs with

patients and assessing their willingness to consider

deprescribing; targeting patients according to highest

risk of adverse drug events; targeting drugs more

likely to be non-beneficial; accessing field-tested

discontinuation regimens for specific drugs; fostering

shared education and training in deprescribing among

all members of the health care team; and undertaking

deprescribing over an extended time frame under the

supervision of a single generalist clinician.

D

eliberate yet judicious deprescribing has consid-

erable potential to relieve unnecessary medica-

tion-related suffering and disability in vulnerable

older populations. Polypharmacy variously defined

as more than five or up to 10 or more medications taken

regularly per individual is common among older

people (defined here as those aged 65 years or over).

Depending on the circumstances, including why and

how drugs are being administered, polypharmacy can

be appropriate (potential benefits outweigh potential

harms) or inappropriate (potential harms outweigh po-

tential benefits).

While many older people benefit immeasurably from

multiple drugs, many others suffer adverse drug events

(ADEs). In Australia, one in four community-living older

people are hospitalised for medication-related problems

over a 5-year period

1

and 15% of older patients attend-

ing general practice report an ADE over the previous 6

months.

2

At least a quarter of these ADEs are potentially

preventable.

2

Up to 30% of hospital admissions for pa-

tients over 75 years of age are medication related, and

up to three-quarters are potentially preventable.

3

Up

to 40% of people living in either residential care

4

or the

community

5

are prescribed potentially inappropriate

medications. In both hospital and primary care settings,

about one in five prescriptions issued for older adults are

deemed inappropriate.

6

Polypharmacy in older people is associated with de-

creased physical and social functioning; increased risk

of falls, delirium and other geriatric syndromes, hospital

admissions, and death; and reduced adherence by patients

to essential medicines. The financial costs are substantial,

with ADEs accounting for more than 10% of all direct

health care costs among affected individuals.

7

The single most important predictor of inappropriate

prescribing and risk of ADEs is the number of medica-

tions a person is taking; one report estimated the risk

as 13% for two drugs, 38% for four drugs, and 82% for

seven drugs or more.

8

One in five older Australians are

receiving more than 10 prescription or over-the-counter

medicines.

9

People in residential aged care facilities are

prescribed, on average, seven drugs,

10

while hospitalised

patients average eight.

11

While hospitalisation might

provide an opportunity to review medication use, on

average, while two to three drugs are ceased, three to

four are added.

12

In responding to polypharmacy-related harm, a new

term has entered the medical lexicon: deprescribing.

This is the process of tapering or stopping drugs using

a systematic approach (Box).

13

Inculcating a culture of

deprescribing will be challenging for several reasons.

Barriers to deprescribing

Underappreciation of the scale of polypharmacy-

related harm

Clinicians easily recognise clinically evident ADEs with

clear-cut causality. In contrast, ADEs mimicking syn-

dromes prevalent in older patients falls, delirium,

lethargy and depression account for 20% of ADEs

in hospitalised older patients but go unrecognised by

clinical teams.

14

Increasing intensity of medical care

The drivers of polypharmacy are multiple: disease-spe cific

clinical guideline recommendations, quality indicators

and performance incentives;

15

a focus on pharmacological

versus non-pharmacological options; and prescribing

cascades, when more drugs are added in response to

onset of new illnesses, including ADEs misinterpreted

as new disease.

First do no harm: a real need to

deprescribe in older patients

Online first 22/09/14

EMBARGO: 12:01am Monday 22 September 2014

Clinical focus

2 MJA 201 (7) 6 October 2014

Narrow focus on lists of potentially inappropriate

medications

Lists of potentially inappropriate medications (such as

the Beers, McLeod and STOPP [Screening Tool of Older

Persons Potentially Inappropriate Prescriptions] criteria)

16

comprise drugs whose benefits are outweighed by harm

in most circumstances. Examples include potent opioids

used non-palliatively, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory

agents, anticholinergic drugs and benzodiazepines.

However, such drugs account for relatively few ADEs in

Australian practice.

17

In contrast, commonly prescribed

drugs with proven benefits in many older people, such

as cardiovascular drugs, anticoagulants, hypoglycaemic

agents, steroids and antibiotics, are more frequently im-

plicated as a result of misuse.

18

Reluctance of prescribers and ambivalence of patients

Many prescribers feel uneasy about ceasing drugs for

several reasons:

19,20

going against opinion of other doctors

(particularly specialists) who initiated a specific drug and

which patients appear to tolerate; fear of precipitating

disease relapse or drug withdrawal syndromes or patient

approbation at having their care downgraded; paucity

of precise benefitharm data for specific medications to

guide selection for discontinuation; apprehension around

discussing life expectancy versus quality of life in ration-

alising drug regimens; limited time and remuneration for

reappraising chronic medications, discussing pros and

cons with patients, and coordinating views and actions

of multiple prescribers.

While agreeing in principle to minimising polyphar-

macy, patients simultaneously express gratitude that their

drugs may prolong life, abate symptoms and improve

function. Fear of relapsing disease lessens patients de-

sire to discontinue a drug, especially if combined with

negative past experiences. Inability to see the personal

relevance of harmbenefit trade-offs or lack of trust

in their doctors advice about drug inappropriateness

and the safety of discontinuation plans also act against

deprescribing.

21

Possible solutions

Ultimately, deprescribing is a highly individualised and

time-consuming process, but several facilitative strat egies

are offered.

Reframe the issue

Both the patient and clinician should regard deprescrib-

ing as an attempt to alleviate symptoms (of drug toxicity),

improve quality of life (from drug-induced disability) and

lessen the risk of morbid events (ADEs) in the future. Its

objective is not simply to reduce the burden, inconveni-

ence or costs of complex drug regimens, although these

too are potential benefits. Deprescribing should not be

seen by patients as an act of abandonment but one of

affirmation for highest quality care and shared decision

making. Compelling evidence that identifies circum-

stances in which medications can be safely withdrawn

while reducing the risk of ADEs and death needs to be

emphasised.

22-25

Discuss benefitharm trade-offs and assess

willingness

In consenting to a trial of withdrawal, patients need to

know the benefitharm trade-offs specific to them of

continuing or discontinuing a particular drug. Patient

education initiatives providing such personalised infor-

mation can substantially alter perceptions of risk and

change attitudes towards discontinuation.

26

Target patients according to highest ADE risk

In addition to medication count, other ADE predictors

include past history of ADEs, presence of major comor-

bidities, marked frailty, residential care settings and

multiple prescribers.

Target drugs more likely to be non-beneficial

Such drugs, as initial targets for deprescribing, consist

of five types.

Drugs to avoid if at all possible (comprising those

previously cited in drugs to avoid lists

16

).

Drugs lacking therapeutic effect for substantiated

indications despite optimal adherence over a reason-

able period of time.

Drugs that patients are unwilling to take for vari-

ous reasons, including occult drug toxicity, difficulty

handling medications, costs and little faith in drug

efficacy.

Drugs lacking a substantiated indication, either be-

cause the original disease diagnosis was incorrect as

often occurs with regard to heart failure, Parkinson

disease and depression or because the stated di-

agnosis-specific indication is invalid owing to evi-

dence of harm or no benefit. Importantly, indications

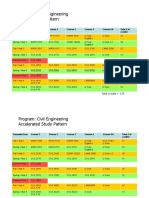

Core themes in deprescribing

13

Ascertain all current medications (medication reconciliation)

Identify patients at high risk of adverse drug events

number and type of drugs

patient characteristics (physical, mental, social impairments)

multiple prescribers

Estimate life expectancy in high-risk patients

with focus on patients with prognosis equal to or less than 12 months

Define overall care goals and patient values and preferences in the context of life

expectancy

relativity of symptom control and quality of life v cure or prevention

patient preference for aggressive v conservative care; willingness to consider

deprescribing

Define and validate current indications for ongoing treatment

medicationdiagnosis reconciliation

drugs lacking valid indications are candidates for discontinuation

Determine time until benefit for preventive or disease-modifying medications

drugs whose time until benefit exceeds expected life span are candidates for

discontinuation

Estimate magnitude of benefit v harm in absolute terms for individual patient

drugs with little likelihood of benefit and/or significant risk of harm are candidates for

discontinuation

Implement and monitor a drug deprescribing plan

ongoing reappraisal for illness relapse or deterioration or withdrawal syndromes

communication of plan and shared responsibility among all prescribers

supervision of drug discontinuation by single generalist clinician

EMBARGO: 12:01am Monday 22 September 2014

3 MJA 201 (7) 6 October 2014

Clinical focus

or treatment targets derived from studies involving

younger patients or highly selected, older individuals

with a single disease may be inappropriate for older,

frail patients with multimorbidity.

Drugs that are unlikely to prevent disease events

within the patients remaining life span. The ques-

tion here is not how much benefit drugs aimed at

preventing future disease events (such as statins and

bisphosphonates) may confer, but when. If the time

until benefit exceeds the patients estimated life span,

no benefit will result, while the ADE risk is constant

and immediate. Undertaking such reconciliations is

facilitated by accurate estimation of longevity using

easy-to-use web-based mortality indices (eg, see http://

eprognosis.ucsf.edu) and drug-specific time until ben-

efit using trial-based time-to-event data.

27

Access and apply specific discontinuation regimens

Detailed descriptions of how clinicians can safely with-

draw specific drugs and monitor for adverse effects can

be found within various articles and websites.

28,29

Foster shared education and training

Interactive, case-based, interdisciplinary meetings involv-

ing multiple prescribers, combined with deprescribing

advice from clinical pharmacologists or appropriately

trained pharmacists have been shown to be beneficial

with regard to doctors deprescribing practice.

30

Extend the time frame with the same clinician

Several patient encounters with the same overseeing

generalist clinician, focused on one drug at a time, can

provide repeated opportunities to discuss and assuage

a patients fear of discontinuing a drug and to adjust the

deprescribing plan according to changes in clinical cir-

cumstances and revised treatment goals. Deprescribing

can be remunerated under extended care or medication

review items, with patients full awareness that such

consultations are expressly for reviewing medications.

Conclusion

Inappropriate polypharmacy and its associated harm

is a growing threat among older patients that requires

deliberate yet judicious deprescribing using a systematic

approach. Widespread adoption of this strategy has its

challenges, but also considerable potential to relieve un-

necessary suffering and disability, as embodied in that

basic Hippocratic dictum first do no harm.

Acknowledgements: Ian Scott and Kristen Anderson were assisted in this research by a

program grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council (grant 1001157).

Competing interests: No relevant disclosures.

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

1 Kalisch LM, Caughey GE, Barratt JD, et al. Prevalence of preventable

medication-related hospitalizations in Australia: an opportunity to reduce

harm. Int J Qual Health Care 2012; 24: 239-249.

2 Miller GC, Britt HC, Valenti L. Adverse drug events in general practice

patients in Australia. Med J Aust 2006; 184: 321-324.

3 Runciman WB, Roughead EE, Semple SJ, Adams RJ. Adverse drug events

and medication errors in Australia. Int J Qual Health Care 2003; 15 Suppl 1:

i49-i59.

4 Staford AC, Alswayan MS, Tenni PC. Inappropriate prescribing in older

residents of Australian care homes. J Clin Pharm Ther 2011; 36: 33-44.

5 Byles JE, Heinze R, Nair BK, Parkinson L. Medication use among older

Australian veterans and war widows. Intern Med J 2003; 33: 388-392.

6 Roughead EE, Anderson B, Gilbert AL. Potentially inappropriate prescribing

among Australian veterans and war widows/widowers. Intern Med J 2007; 37:

402-405.

7 Gyllensten H, Rehnberg C, Jnsson AK, et al. Cost of illness of patient-

reported adverse drug events: a population-based cross-sectional survey.

BMJ Open 2013; 3: e002574.

8 Atkin PA, Veitch PC, Veitch EM, Ogle SJ. The epidemiology of serious adverse

drug reactions among the elderly. Drugs Aging 1999; 14: 141-152.

9 Parkes AJ, Coper LC. Inappropriate use of medications in the veteran

community: how much do doctors and pharmacists contribute? Aust N Z J

Public Health 1997; 21: 469-476.

10 Elliott RA, Thomson A. Assessment of a nursing home medication review

service provided by hospital-based clinical pharmacists. Aust J Hosp Pharm

1998; 29: 255-260.

11 Woodward MC, Elliott RA, Oborne CA. Quality of prescribing for elderly

inpatients at nine hospitals in Victoria, Australia. J Pharm Pract Res 2003; 33:

101-105.

12 Crotty M, Rowett D, Spurling L, et al. Does the addition of a pharmacist

transition coordinator improve evidence-based medication management and

health outcomes in older adults moving from the hospital to a long-term care

facility? Results of a randomized, controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother

2004; 2: 257-264.

13 Scott IA, Gray LC, Martin JH, et al. Deciding when to stop: towards evidence-

based deprescribing of drugs in older populations. Evid Based Med 2013; 18:

121-124.

14 Klopotowska JE, Wierenga PC, Smorenburg SM, et al. Recognition of adverse

drug events in older hospitalized medical patients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2013;

69: 75-85.

15 Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, et al. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care

for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: implications for pay for

performance. JAMA 2005; 294: 716-724.

16 Spinewine A, Schmader KE, Barber N, et al. Appropriate prescribing in elderly

people: how well can it be measured and optimised? Lancet 2007; 370:

173-184.

17 Miller GC, Valenti L, Britt H, Bayram C. Drugs causing adverse events in

patients aged 45 or older: a randomised survey of Australian general practice

patients. BMJ Open 2013; 3: e003701.

18 Budnitz DS, Lovegrove MC, Shehab N, Richards CL. Emergency

hospitalizations for adverse drug events in older Americans. N Engl J Med 2011;

365: 2002-2012.

19 Anthierens S, Tansens A, Petrovic M, Christiaens T. Qualitative insights into

general practitioners views on polypharmacy. BMC Fam Pract 2010; 11: 65.

20 Schuling J, Gebben H, Veehof LJ, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM. Deprescribing

medication in very elderly patients with multimorbidity: the view of Dutch

GPs. A qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract 2012; 13: 56.

21 Reeve E, To J, Hendrix I, et al. Patient barriers to and enablers of deprescribing:

a systematic review. Drugs Aging 2013; 30: 793-807.

22 Iyer S, Naganathan V, McLachlan AJ, Le Couteur DG. Medication withdrawal

trials in people aged 65 years and older: a systematic review. Drugs Aging

2008; 25: 1021-1031.

23 Declercq T, Petrovic M, Azermai M, et al. Withdrawal versus continuation of

chronic antipsychotic drugs for behavioural and psychological symptoms in

older people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; (3): CD007726.

24 Gallagher PF, OConnor MN, OMahony D. Prevention of potentially

inappropriate prescribing for elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial

using STOPP/START criteria. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2011; 89: 845-854.

25 Garnkel D, Zur-Gil S, Ben-Israel J. The war against polypharmacy: a new cost-

efective geriatric-palliative approach for improving drug therapy in disabled

elderly people. Isr Med Assoc J 2007; 9: 430-434.

26 Martin P, Tamblyn R, Ahmed S, Tannenbaum C. A drug education tool

developed for older adults changes knowledge, beliefs and risk perceptions

about inappropriate benzodiazepine prescriptions in the elderly. Patient Educ

Couns 2013; 92: 81-87.

27 NHS Highland. Polypharmacy: guidance for prescribing in frail adults.

http://www.nhshighland.scot.nhs.uk/publications/documents/guidelines/

polypharmacy guidance for prescribing in frail adults.pdf (accessed Jun 2014).

28 Farrell B, Merkley VF, Thompson W. Managing polypharmacy in a 77-year-old

woman with multiple prescribers. CMAJ 2013; 185: 1240-1245.

29 Best Practice Advocacy Centre New Zealand. A practical guide to stopping

medicines in older people. Best Practice Journal 2010; 27 Apr. http://www.

bpac.org.nz/magazine/2010/april/stopGuide.asp (accessed Nov 2013).

30 Bregnhj L, Thirstrup S, Kristensen MB, et al. Combined intervention

programme reduces inappropriate prescribing in elderly patients exposed to

polypharmacy in primary care. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2009; 65: 199-207.

EMBARGO: 12:01am Monday 22 September 2014

Вам также может понравиться

- Drowning Prevention Report, Sri Lanka 2014Документ21 страницаDrowning Prevention Report, Sri Lanka 2014caffyw100% (1)

- Reviving Ocean Economy: A Call For Action - 2015Документ60 страницReviving Ocean Economy: A Call For Action - 2015caffywОценок пока нет

- Oral Therapy Could Provide Treatment For Peanut AllergiesДокумент16 страницOral Therapy Could Provide Treatment For Peanut AllergiescaffywОценок пока нет

- Landscape of Violence Report Finds Rural and Regional Victorian Women More Likely To Experience ViolenceДокумент217 страницLandscape of Violence Report Finds Rural and Regional Victorian Women More Likely To Experience ViolencecaffywОценок пока нет

- Open Letter To The VCs of Australian UniversitiesДокумент6 страницOpen Letter To The VCs of Australian UniversitiescaffywОценок пока нет

- Tunnel Vision or World Class Public Transport?Документ16 страницTunnel Vision or World Class Public Transport?caffywОценок пока нет

- Can Broccoli Cure Autism?Документ3 страницыCan Broccoli Cure Autism?caffywОценок пока нет

- TWT East Timor Response Department, Foreign Affairs, Trade ResponseДокумент1 страницаTWT East Timor Response Department, Foreign Affairs, Trade ResponsecaffywОценок пока нет

- European Spine JournalДокумент1 страницаEuropean Spine JournalcaffywОценок пока нет

- The Benefits and Harms of DeprescribingДокумент4 страницыThe Benefits and Harms of DeprescribingcaffywОценок пока нет

- PM: Email From The Chief Minister of Sri LankaДокумент1 страницаPM: Email From The Chief Minister of Sri LankacaffywОценок пока нет

- Councils To Be Abolished PDFДокумент2 страницыCouncils To Be Abolished PDFLatika M BourkeОценок пока нет

- Letter To The High CommissionerДокумент2 страницыLetter To The High CommissionercaffywОценок пока нет

- FINAL DeprescribingДокумент2 страницыFINAL DeprescribingcaffywОценок пока нет

- Autism Spectrum Australia Summary ReportДокумент7 страницAutism Spectrum Australia Summary ReportcaffywОценок пока нет

- Compensation Claims Made by Asylum Seekers Between 1999 and 2011Документ2 страницыCompensation Claims Made by Asylum Seekers Between 1999 and 2011caffywОценок пока нет

- Newport Police Department Report On Aaron AlexisДокумент3 страницыNewport Police Department Report On Aaron AlexisEyder PeraltaОценок пока нет

- European Spine Journal 2Документ7 страницEuropean Spine Journal 2caffywОценок пока нет

- Reporting Racism ReportДокумент68 страницReporting Racism ReportcaffywОценок пока нет

- Facilitating Wolbachia Introductions Into Mosquito Populations Through Insecticide-Resistance SelectionДокумент9 страницFacilitating Wolbachia Introductions Into Mosquito Populations Through Insecticide-Resistance SelectioncaffywОценок пока нет

- European Spine JournalДокумент1 страницаEuropean Spine JournalcaffywОценок пока нет

- European Spine Journal 2Документ7 страницEuropean Spine Journal 2caffywОценок пока нет

- European Spine JournalДокумент1 страницаEuropean Spine JournalcaffywОценок пока нет

- Letter To UK - PMДокумент3 страницыLetter To UK - PMcaffywОценок пока нет

- Coding Letter To Canadian War MuseumДокумент2 страницыCoding Letter To Canadian War MuseumcaffywОценок пока нет

- Bishop Michael Kennedy's Letter To His ParishДокумент2 страницыBishop Michael Kennedy's Letter To His ParishcaffywОценок пока нет

- Lion Range State Ranking Dec 2012Документ12 страницLion Range State Ranking Dec 2012caffywОценок пока нет

- DNA Paper Smear Cancer Paper Science Translational MedicineДокумент11 страницDNA Paper Smear Cancer Paper Science Translational MedicinecaffywОценок пока нет

- Artillery MapДокумент1 страницаArtillery MapcaffywОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Guidelines For Doing Business in Grenada & OECSДокумент14 страницGuidelines For Doing Business in Grenada & OECSCharcoals Caribbean GrillОценок пока нет

- CHN Nutri LabДокумент4 страницыCHN Nutri LabMushy_ayaОценок пока нет

- PDF BrochureДокумент50 страницPDF BrochureAnees RanaОценок пока нет

- Present Tenses ExercisesДокумент4 страницыPresent Tenses Exercisesmonkeynotes100% (1)

- PM 50 Service ManualДокумент60 страницPM 50 Service ManualLeoni AnjosОценок пока нет

- Electronics 11 02566Документ13 страницElectronics 11 02566卓七越Оценок пока нет

- HKUST 4Y Curriculum Diagram CIVLДокумент4 страницыHKUST 4Y Curriculum Diagram CIVLfrevОценок пока нет

- Investigation Data FormДокумент1 страницаInvestigation Data Formnildin danaОценок пока нет

- Abas Drug Study Nicu PDFДокумент4 страницыAbas Drug Study Nicu PDFAlexander Miguel M. AbasОценок пока нет

- The Marriage of Figaro LibrettoДокумент64 страницыThe Marriage of Figaro LibrettoTristan BartonОценок пока нет

- Bill of Quantities 16FI0009Документ1 страницаBill of Quantities 16FI0009AJothamChristianОценок пока нет

- SPFL Monitoring ToolДокумент3 страницыSPFL Monitoring ToolAnalyn EnriquezОценок пока нет

- Vq40de Service ManualДокумент257 страницVq40de Service Manualjaumegus100% (4)

- Agenda - 2 - Presentation - MS - IUT - Thesis Proposal PPT Muhaiminul 171051001Документ13 страницAgenda - 2 - Presentation - MS - IUT - Thesis Proposal PPT Muhaiminul 171051001Tanvir AhmadОценок пока нет

- Formato MultimodalДокумент1 страницаFormato MultimodalcelsoОценок пока нет

- Kortz Center GTA Wiki FandomДокумент1 страницаKortz Center GTA Wiki FandomsamОценок пока нет

- Pediatric Fever of Unknown Origin: Educational GapДокумент14 страницPediatric Fever of Unknown Origin: Educational GapPiegl-Gulácsy VeraОценок пока нет

- Revenue Memorandum Circular No. 55-2016: For ExampleДокумент2 страницыRevenue Memorandum Circular No. 55-2016: For ExampleFedsОценок пока нет

- API RP 7C-11F Installation, Maintenance and Operation of Internal Combustion Engines.Документ3 страницыAPI RP 7C-11F Installation, Maintenance and Operation of Internal Combustion Engines.Rashid Ghani100% (1)

- Saudi Methanol Company (Ar-Razi) : Job Safety AnalysisДокумент7 страницSaudi Methanol Company (Ar-Razi) : Job Safety AnalysisAnonymous voA5Tb0Оценок пока нет

- Managing Errors and ExceptionДокумент12 страницManaging Errors and ExceptionShanmuka Sreenivas100% (1)

- Concise Selina Solutions Class 9 Maths Chapter 15 Construction of PolygonsДокумент31 страницаConcise Selina Solutions Class 9 Maths Chapter 15 Construction of Polygonsbhaskar51178Оценок пока нет

- FluteДокумент13 страницFlutefisher3910% (1)

- Chapter1 Intro To Basic FinanceДокумент28 страницChapter1 Intro To Basic FinanceRazel GopezОценок пока нет

- Dependent ClauseДокумент28 страницDependent ClauseAndi Febryan RamadhaniОценок пока нет

- Institutions and StrategyДокумент28 страницInstitutions and StrategyFatin Fatin Atiqah100% (1)

- Properties of WaterДокумент23 страницыProperties of WaterNiken Rumani100% (1)

- Oil List: Audi Front Axle DriveДокумент35 страницOil List: Audi Front Axle DriveAska QianОценок пока нет

- Subeeka Akbar Advance NutritionДокумент11 страницSubeeka Akbar Advance NutritionSubeeka AkbarОценок пока нет

- E-CRM Analytics The Role of Data Integra PDFДокумент310 страницE-CRM Analytics The Role of Data Integra PDFJohn JiménezОценок пока нет