Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Session 1E Salmon, Murdock

Загружено:

NCVO0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

28 просмотров16 страницPresented at the 20th Voluntary Sector and Volunteering Research Conference, 10-11 September 2014.

http://www.ncvo.org.uk/training-and-events/research-conference

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документPresented at the 20th Voluntary Sector and Volunteering Research Conference, 10-11 September 2014.

http://www.ncvo.org.uk/training-and-events/research-conference

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

28 просмотров16 страницSession 1E Salmon, Murdock

Загружено:

NCVOPresented at the 20th Voluntary Sector and Volunteering Research Conference, 10-11 September 2014.

http://www.ncvo.org.uk/training-and-events/research-conference

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 16

`

Prohibiting, policing, permitting or

promoting? The interaction

between the policy and practice of

governments and the strategic

choices of NGOs in work with

vulnerable children and families

Voluntary Sector and Volunteering

Research Conference 2014

Hugh Salmon, Family for Every Child and Centre for Government and

Charity Management, London South Bank University

Professor Alex Murdock, Centre for Government and Charity

Management, London South Bank University

Introduction

Between 2009 and 2012 several countries, including Ethiopia, Russia and Moldova, debated or

enacted legislation increasing scrutiny and control over NGOs

1

, but for somewhat different

purposes.

2

This paper summarises research that explored how NGOs, faced with restrictive, and

at times contradictory, government policies and practices, adjust their strategic focus and tactics

in such a way as to still achieve their goals. The research was framed to examine two areas:

How do governments differ in their behaviour towards NGOs, both in the laws and

policies they set and in practice?

How do national NGOs in their countries respond strategically to the constraints and

opportunities presented by these policies and practices?

Following unrest and uprisings, between 2003 and 2005, in Georgia, Ukraine and Kyrgyzstan,

many other governments began to fear their national NGOs, influenced by foreign funders,

might play a role in provoking public protest. This sense of increasing mistrust of NGOs was

evident in the laws and policies adopted by the Russian and Ethiopian governments. This

research, interviewing representatives of NGOs working with children in nine countries, found

that mistrust of national NGOs, and a wish to restrict their activities, is a common element of

government policy and practice in a range of countries. However, it was also found that there is

in fact a spectrum of government approaches towards NGOs, summarised in this research as

ranging from policing or prohibiting, to permitting and promoting.

The observation that government policy and practice towards civil society varies across a wide

spectrum is not new. Najam (2000) identifies four main type of relationship: cooperative,

complementary, co-optive, and confrontational. In contrast to the trend towards greater

restriction on the activities of NGOs in several countries, in other countries researchers have

1

The term Non-Governmental Organisation is used in this paper, in preference to the now more widely used term, Civil Society

Organisation, because NGO has for a longer period been used to describe the non-state, non-commercial organisations working in

international development. Whereas CSOs represent the full range of size, purpose and form of organisations within civil society,

(Salamon, 2003, p.10), the term NGO tends to be more narrowly used to refer to organisations with the purpose and capacity to deliver

aid or services. The type of national, service-providing NGOs that are the focus of this study are typically led by professional managers

rather than volunteers from the communities they serve, and are generally financed by grants from donors, or grants or contracts from

government. This has led NGOs to be criticised for claiming to deliver services for or speak on behalf of poor or marginal groups, while

allowing little scope for such people to scrutinise their work or hold them to account. The Economist in 1999 asserted that NGOs are

increasingly acting as unelected and unaccountable special-interest groups, [which] disrupt global governance. This study does not

attempt to refute such assertions, but nonetheless considers them worthy of study, from a pragmatic perspective, based on their key role

in delivering services to groups that many governments fail to reach.

2

In Moldova a law was drafted to enable NGOs to bid for contracts to deliver services, thus increasing access to and quality of services, but

the first draft was highly restrictive in terms of requirements for accreditation.

In Russia, the Federal Law Introducing Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts of the Russian Federation Regarding the Regulation of

Activities of Non-commercial Organizations Performing the Function of Foreign Agents, passed by the Duma in July 2012, required all

non-commercial organizations (NCOs) to register with the Ministry of Justice, prior to receipt of funding from any foreign sources if they

intend to conduct political activities. These would then be named "NCOs carrying functions of a foreign agent." International Centre for

Not for Profit Law (2012).

In Ethiopia the Proclamation to Provide for the Registration and Regulation of Charities and Societies, January 2009 , led to legislation

preventing NGOs receiving more than 10% of their income from international sources from working in areas considered politically

sensitive - governance, human rights, conflict resolution or criminal justice.

found NGOs still able to work quietly and constructively with government and local authorities,

innovating new models of service delivery, and improving policy and legislation. Fioramonti and

Heinrich (2007), in reviewing CIVICUS Civil Society Index reports in nine countries in Eastern

Europe, found that civil society groups can work effectively to influence policy, through policy

consultations, in demonstrating new ways of working and through advocacy activities, both

publicly and behind the scenes through direct contact with politicians and officials.

The question which then arises is how, faced with often sensitive and restrictive regimes, can

NGOs achieve an optimal balance of service delivery with advocacy in such a way as to maintain

their autonomy, authority and legitimacy. This study set out to identify whether and how NGOs

achieve this balance, and whether they find service delivery and advocacy, plus technical

assistance, to be incompatible or complementary strategic priorities.

Research Methods

This research was based on a mix of qualitative methods, best suited to explore in some depth

the nature of the relationship between government policy and practice towards NGOs and NGO

strategy in response. The researcher selected a purposive and pragmatic sample of ten

participants, based on ease of access from existing working contacts with their organisations. The

individuals were senior representatives of national NGOs working with vulnerable children and

families in Azerbaijan, Ethiopia, Georgia, Ghana, Guyana, Moldova, Russia and Zimbabwe, plus

representatives of two such NGOs in Nepal. Even though this sample of countries does not

represent all regions it does represent diverse social, economic and political contexts. Data

collection was conducted via two focus group discussions

3

with three participants each, and

individual interviews with four participants unavailable to participate in focus groups. Both

interviews and focus group discussions explored participants experience of government policy

and practice towards NGOs, using as reference points a proposed spectrum of typical

government traits 1. Prohibiting, 2. Policing, 3. Passive (or incompetent), 4. Permitting, 5.

Promoting. The participants were then invited to share up to three examples of changes in

government policy and practice in the past five years. Finally, participants were asked to reflect on

how NGOs, in response, balance service delivery, advocacy and technical assistance in their

strategic focus. All the interviews and focus groups were recorded and then transcribed. The

transcripts were then analysed against emerging themes and initial assumptions.

3

One focus group was composed of low income (Ethiopia and Zimbabwe) and lower middle income (Ghana) countries in sub-Saharan

Africa. The other group had a more contrasting representation of lower middle income countries from quite different regions (Georgia

and Guyana) plus Russia, a high income country, based on national income levels as defined and assessed by the World Bank.

http://data.worldbank.org/country

Findings

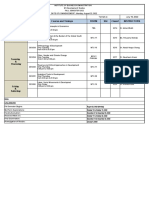

Data analysis of the participants categorisation of their governments policy and practice towards

NGOs revealed some interesting patterns, with six out of ten describing them as permitting, as

shown below:

Table 1

1

Prohibiting

restrict

2

Policing

regulate

3

Passive

(incl. indifferent,

incompetent or

corrupt)

4

Permitting

facilitate

5

Promoting

encourage

Russia

Ethiopia

Guyana Georgia

Zimbabwe

Ghana

Azerbaijan

Nepal 1

Moldova

Nepal 2

An overall finding was that the views of the participants in this study bore little resemblance to

CIVICUS Civil Society Index

4

scores for the environment faced by CSOs, previously assigned to

five countries

5

in this study.

4

The two most widely used tools for measuring civil society (Lyons, 2009) originate from the late 1990s: the Civil Society Index (CSI)

developed by CIVICUS (Heinrich, 2007) , and the Global Civil Society Index (GCSI), developed by the Center for Civil Society Studies at

Johns Hopkins University (Salamon & Sokolowski, 2004). For this study, the CSI is more applicable, since CSI assessments, using

participatory methods, have been carried out in five of the nine countries included, while the GCSI has not been completed in any of them.

The CSI also includes a range of indicators for not just the strength and vitality of civic groups, but their impact and the environment in

which they operate. The CSI scores for environment were considered in this research as a comparative measure of the context in which

the NGOs in this study are operating.

5

The Nepali participants rated their government at the more positive end of the spectrum, in contrast to Nepals low CSI environment

score of 1.3 (though the score was assigned in 2006, before the restoration of democracy which has enabled a more favourable

environment for civil society). The Russian participant, by contrast, put their government in the restrictive category, in contrast to the

relatively high CSI environment score assigned to that country in 2009,1.59 (though the CSI findings predate the more restrictive law on

NGOs passed by Russias Duma in 2012).The CSI scores for civil society environment for these countries (a higher score represents a more

favourable environment) were: Azerbaijan (2007) 1.1, Nepal (206) 1.3, Ghana (2006) 1.5, Russia (2009) 1.59, Georgia (2010) 1.7. (Dates

the scores were assessed are in brackets). From 2008, CSI scores were calculated on a 0 100 scale, but for the sake of comparability the

Georgia and Russia scores have been converted, so that all are shown as scores out of 3.

All respondents gave at least two examples of significant changes and developments in

government policy and practice towards NGOs in their sector in the past five years. The majority

of these examples were positive. Less than one fifth of changes or developments that participants

recalled were experienced as wholly negative (see Table 2). However there were examples when

a generally positive ranking on the spectrum of government traits did not match the examples

provided; in particular the Ghanaian and Georgian participants, who rated their governments as

permitting, but recalled no wholly positive changes in the governments approach in the last five

years.

Table 2: Countries ranked by proportion of changes / developments rated as positive

(positive changes scored 1 point, mixed 0 and negative -1)

Azerbaijan 3 (3 positive changes)

Nepal 3 (3 positive, 1 mixed combined score of 2 NGOs)

Guyana & Moldova 2 (2 positive, 1 mixed)

Zimbabwe 1 (2 positive, 1 negative)

Russia 1 (1 positive, 2 mixed)

Ethiopia 0 (1 positive, 1 negative)

Ghana -1 (1 negative, 1 mixed)

Georgia -2 (2 negative, 1 mixed)

An unexpected finding in response to the first and second question was the positive

categorisation of the government of Azerbaijan by the participant from that country, and her

recollection of three recent positive developments, contrasted with the more negative remarks

of her counterpart from Ghana. These responses contradict what would have been predicted on

the basis of the CSI scores for these countries, which score Ghana more favourably than

Azerbaijan. What such unexpected findings most reveal is how differently individual NGOs may

perceive and experience recent trends in their countries, compared to what one would assume

to be the case based on published reports or data on those countries.

The final question asked respondents to place their NGOs on a triangular spectrum of strategic

options (figure 1), and to plot the direction of any strategic change, in their organisations

balance of focus between technical assistance, service delivery and advocacy. Three of the NGOs

reported a focus on one approach (Ghana on service delivery, Ethiopia on technical assistance

and the second Nepali participant on advocacy). Three NGOs said they balance two approaches

(Guyana and Zimbabwe: service delivery and advocacy; Moldova: technical assistance and

advocacy). Finally, three NGOs said they balance all three approaches: for the participant from

Azerbaijan this meant an absolutely equal balance of all three, but for one Nepali participant

slightly less emphasis on service delivery than the other two options, and for the participant from

Russia slightly less emphasis on technical assistance.

Figure 1

Technical Assistance

All of the participants that identified an intended direction of change of strategic focus stated

some degree of preference for working more on technical assistance, apart from Zimbabwe for

whom the priority was to focus more on advocacy. Ghana and Guyana identified a need to

increase both technical assistance and advocacy, whereas the second Nepali participant

highlighted a need to shift more to service delivery as well as technical assistance. The NGOs

from Moldova and Azerbaijan were confident with their current strategic balance so did not see

a need to change it.

Classification of government policy and practice

Analysis of collected data revealed four broad categories of government policy and practice.

Type A: Prohibiting and policing, mistrust and restriction.

Type B: Passive indifference, incompetence or corruption.

Type C: Permitting and promoting

Type D: Permitting and promoting, but inconsistently

Ghana Guyana

Nepal2 Zimbabwe

Russia

Nepal 1

Ethiopia

Moldova

Azerbaijan

Service delivery

Advocacy

Participants observations of how they experienced each of these categories in their working

relationships with government are summarised below.

Type A: Prohibiting and policing, mistrust and restriction

Restrictive legislation, regulation and monitoring

Most participants experienced some form of government restriction, but the starkest examples

of recent restrictive laws on NGOs were from Ethiopia and Russia. In Ethiopia, the law passed in

2009 prohibited national NGOs that are more than 10% funded by foreign sources from

working on governance, human rights, conflict resolution, or criminal justice issues, with further

more recent restrictions on their expenditure

6

. The Russian participant emphasised the restrictive

environment faced by NGOs, not only as a result of the recent law classifying foreign-funded

NGOs as foreign agents and greatly restricting their work, but also in the generally close

surveillance of the work of NGOs

7

. Also mentioned as a major constraint on NGOs, was

excessive bureaucracy and tight regulation and monitoring. The Ethiopian participant described

increasing regulatory hurdles, requiring re-registration, and bureaucratic requirements by various

government departments, restricting not only their work but their ability to secure foreign grants.

Hostile behaviour and threats

Several participants referred to threats of closure or ad hoc bans on certain activities based on

suspicion of foreign or political influence, in particular in the case of Zimbabwe. However, the

Zimbabwean participant also noted that NGOs are generally left alone to carry out their work if

they continue to focus on their core child protection remit. She also noted that the level of

interference was varied according to the political atmosphere, increasing before elections when

politicians feared NGOs could influence voters. The participants from Ghana, Guyana and Nepal

all mentioned that their governments at times try to influence donors choice of local NGO

partners indirectly, through negative comments about certain NGOs.

Lack of trust and defensiveness

While some participants linked governments lack of trust to suspicion of the influence of foreign

funding, in Guyanas case there seemed to be a general reluctance to share responsibility for child

protection, despite the governments lack of capacity in this field. In Georgia, the participant

described how the previous government had enabled a greater role for NGOs in service delivery,

but become more resistant to advocacy, and defensive in response to criticism of the new

outsourced services. NGO service providers voicing public criticism could face public rebuke or a

reduction of their contract. This defensiveness was also manifest in the Georgian governments

refusal to allow NGOs to carry out monitoring and evaluation of public services.

6

A more recent guideline has restricted to 30% of expenditure the amount that Ethiopian charities can spend on

administration, as opposed to direct service delivery. The participant from Ethiopia explained that administration has been

broadly defined by the government as including research and technical assistance activities, and most staff salary costs.

7

The government very closely monitors what theyre actually doing these NGOs and if they are doing something that the

government it is not liking they could just be shut down. Russian participant, in focus group.

Type B: Passive indifference, incompetence or corruption:

Lack of defined policy or interest in strategic cooperation with NGOs

The participant from Guyana in particular spoke of the government apathy and lack of a strategic

approach, failure to respond to NGO policy initiatives and lack of interest in supporting NGO-

run services, though at times relying on them. The Russian federal government was described as

indifferent and detached in its relationship with NGOs.

Lack of transparency

Several participants referred to some degree of lack of transparency in governments interaction

with NGOs, particularly in relation to funding decisions. In both Azerbaijan and Russia,

participants mentioned that contracting services, in one sense a welcome development if it

involves a truly open tender, is often influenced by corruption or conducted unfairly, with certain

NGOs favoured.

Lack of government capacity to regulate, monitor and evaluate NGOs

The inability to carry out objective monitoring, and its negative consequences for NGOs, was

described in detail by the participant from Azerbaijan. The second Nepali participant spoke of

corruption and nepotism undermining the objectivity of monitoring, but welcomed monitoring

and evaluation when done well as immensely useful for both government and NGO.

Corruption, especially in relation to donor funds and enforcement of

regulations

This was cited as a concern in Georgia, Guyana and Nepal, with corrupt practices and political

bias evident in the interaction between government and NGOs, and often on both sides

8

. The

participant from Guyana recounted experiences of donor funding for NGOs, to be disbursed via

government, not reaching the intended beneficiaries. One Nepali participant spoke of officials

seeking commission in return for not imposing fines for breach of regulations, or for access to a

grant.

Type C: Permitting and Promoting

A more constructive and cooperative type of relationship was illustrated by many examples of

how even governments resistant to perceived criticism, through public advocacy, can be

receptive to NGOs demonstrating new services or providing technical assistance, or willing to

contract their services.

Clear policy commitment to cooperate with NGOs

8

there are many organisations that are corrupted, and bureaucrats are also corrupted, and then there is a link between the

NGOs and political parties and the bureaucrats also. Nepali participant, in interview.

In contrast to those participants describing their government as indifferent or lacking a clear

policy, several participants experienced a commitment to work with NGOs in meeting national

development goals or implementing national action plans, sometimes under the influence of

donors. In both Nepal and Zimbabwe, this commitment was made with the arrival of a new

government.

Grants and contracts are provided fairly

Again in contrast to those governments showing type B traits, the participants from Georgia and

Moldova in particular spoke of direct government funding for national NGOs, through grants or

tenders for contracts. Georgias government had already begun to outsource services to NGOs.

Moldova, and to a lesser extent Azerbaijan, had begun the process of developing laws and

regulations to enable accreditation and contracting of non-state service providers. Despite her

criticism of some lack of transparency and favouritism, the Russian participant did identify

mechanisms for state funding at three different administrative levels, as well as increasing access

to grants from large state corporations.

9

Clear regulation and monitoring, enabling trust and fairness in government

NGO cooperation

In contrast to international criticism of restrictive legislation, in particular the new Ethiopian and

Russian laws, it was the view of many of participants, including from these countries, that a

benefit of well organised regulation and monitoring is that public trust in NGOs increases, and

government-NGO relations are experienced as fair and transparent. The participant from Ghana

was highly critical of his government for not having acted on NGO calls for the 1961 law still

used to regulate NGOs to be updated. The participant from Azerbaijan, rather than criticising the

government for harsh measures applied in particular against human rights groups, expressed

support for the governments reasons for seeking to apply restrictions on NGOs.

10

Positive consultation with NGOs

The participants from Azerbaijan, Moldova and Nepal spoke positively of bodies set up to enable

consultation with NGOs producing results. The Moldovan participant gave an example of NGOs

working together to apply for a draft law, on accreditation of service providers, to be amended.

The Ghanaian participants experience, however, was that the government was willing to invite

national NGOs to consultation meetings but not to contract them to provide services or

technical assistance.

Technical cooperation with NGOs to pilot new services that governments can

9

They [state-owned corporations] are investing huge resources in social areas in the regions where they have presencethe fact

that there is more money available from the corporate sector is a positive thing because in a way they are affecting the changes to

the social policies. Russian participant, in focus group.

10

there was just recently a law that any grant or donation needs to be registered with the Ministry of Justice. Now the NGO

community are up in arms about it but I understand: of course they want to see whos getting what money from where for what,

its understandable. And if youre doing a proper job its nothing to worry about. Azerbaijan participant, in interview.

then scale up

In such cases, NGOs felt their efforts were leading to positive change on a nationwide scale and a

sustainable basis. The successful demonstration, testing and refinement of new service models,

later scaled up by the government, was a particular theme of the Moldovan participants account

of the impact achieved by her NGO over an extended period, but also referred to in Georgia and

Ethiopia.

Type D: Permitting and promoting, but inconsistently

Cooperation, but only by certain ministers or departments, or with a select

number of NGOs

The Guyanese participant mentioned that cooperation often depends on the attitude or political

motives of the minister in charge at the time, though at lower levels of government there may be

greater and more consistent willingness to cooperate with the mutual aim of improving services.

In Zimbabwe and Nepal changes of government and of ministers were experienced as a major

cause of inconsistency and uncertainty in relations with government. In Moldova and Russia,

concerns were mentioned that the opportunities for consultation, and to apply for contracts,

were often restricted only to a few NGOs.

Governments are opportunistic or self-interested

The Georgian participant said that positive cooperation occurs when a government partner sees

their political interests as aligned with that of the NGO. In such cases a minister may even permit

NGOs to advocate publicly on the issue. A common experience was of governments main

interest in working with NGOs being to gain access to funding, particularly for governments in

lower income countries reliant on donor funding. For example, accessing donor funds through

cooperation with NGOs was a greater preoccupation for the government of Guyana than for

that of Azerbaijan, which can support its work through oil and gas revenues. Participants from

Ethiopia, Guyana, Russia and Zimbabwe complained that their governments motivation to

cooperate with NGOs is often simply to take the credit for NGOs successes. Even if this meant,

as described in Guyana, distorting reality to give the impression that a successful project was were

their initiative.

Governments make but fail to keep promises to support or fund NGOs

In Moldova examples of policy commitments not being fulfilled were seen to result from poor

organisation, while in Nepal the failures were blamed on a lack of will and persistent mistrust of

NGOs. Direct budget support for governments by donors was experienced by some participants,

in particular in Guyana and Moldova. This was promoted following the Paris Declaration on Aid

Effectiveness (2005) though in some cases has been reversed or suspended owing to donor

concerns that governments are not meeting commitments to human rights or democratisation.

While the Paris agenda principle of national ownership and coordination of funding was

welcomed by some participants, and did enable some governments to fund non-state service

provision, their actual experience of direct budget support was that it reduced national NGOs

access to funds considerably. In Moldova the European Union had made commitments to direct

budget support, but the NGO representative noted that this was experienced as a mixed

blessing, in particular as government disbursed funds to NGOs for service delivery but not for

advocacy or monitoring.

11

NGO strategy and tactics in response to government

policy and practice

Seven main strategic approaches were identified from participants responses:

1. Building bridges and relationships with those in power

There were frequent references to the importance of the NGO being in a positive, trusting

relationship with government counterparts. This meant being, variously: humble, flexible,

opportunistic and well prepared. Suggested tactics included allowing politicians to take the credit

for successes and, as detailed by the participant from Azerbaijan

12

, careful timing, targeting and

planning in submission of proposals.

2. Working closely with donors can facilitate cooperation with government, if

NGO independence is also maintained

In most countries in this study, apart from Russia, the key donor is UNICEF

13

. The need to take

into account UNICEFs plans and priorities, when working with government, was noted by the

participant from Guyana. Others, including a participant from Nepal, criticised the tendency of

some NGOs to become dependent on donor opportunities as they run the risk of losing local

credibility and authority, and being seen as more influenced by the agenda of foreign donors

than the needs of their local stakeholders.

3. Advocacy is better received by governments when framed in terms of

upholding social and economic rights, rather than civil or political rights

The experience of participants from Ethiopia, Russia and Zimbabwe was that NGOs that speak

up on issues that a government finds politically sensitive face restrictions, reprisals and threats of

closure. Such governments tend to regard NGOs as legitimate only in so far as they are able to

11

I started to speak to the Minister by saying that I can see that youre very happy that much of the money now comes directly to

you but I think that you cant have a democratic society... without having good conditions for the NGOs to be credible partners for

you to monitor what the government and the local authorities do. Moldovan participant, in interview.

12

This is the kind of government you just have to get everything done for them, present them with a ready package rather than

trying to talk them round and waiting for them to do something. if you want something done you have to bring it to the table

yourself I think with advocacy its about catching the right person at the right time. Azerbaijan participant, in interview.

13

UNICEF is the UN childrens agency. Strictly speaking it is a multi-lateral implementing partner rather than a donor as it also

relies on donor funds for its work, some of which it then sub-grants or contracts to NGOs. In Russia UNICEF was asked to close

its country programme in 2012, even though, as the participant noted, they had been playing a key role as an intermediary

between NGOs and government.

deliver needed services. The participant from Azerbaijan emphasised that highlighting the rights

of families to access certain services is better received than broader rights-based appeals. The

participant from Moldova emphasised the vital role for childrens NGOs of ensuring childrens

views can influence policy development. She described how her NGOs recent focus on enabling

child participation in improving services had led government and local authorities to accept the

benefits of a more inclusive approach to policy making.

4. Taking a long-term, patient approach

Determination and persistence were the other ingredients of success described by the participant

from Moldova, with breakthroughs often following long periods with little government

cooperation. Four other participants gave examples of the benefits of a long-term, carefully

planned and targeted approach. The Guyanese participant, in particular, spoke of the benefits of

the NGO remaining focused on a clear agenda over a period of time, in working with

government, even if there are frequent changes of minister.

5. Forming an alliance can strengthen NGOs voice and influence

Several participants described how their influence was amplified when they formed a coalition,

which, as was the case in Nepal, can sometimes elect a representative to join national consultative

bodies. Participants from both Ethiopia and Moldova stressed the need for partnership and

consultation between NGOs also to involve local community groups and enable direct

participation by children, to strengthen their representativeness and relevance.

6. Focusing on technical assistance rather than advocacy can be a more

effective way to influence policy and improve services

In some countries where advocacy is prohibited, such as Ethiopia, the government was found still

to be open to expert, solution-focused advice and practical demonstration. In such cases NGOs

help officials see the problem and possible solutions for themselves rather than making public

statements. In Russia, the participant said the authorities are receptive if presented with clear

evidence of what works. The participant from Moldova recommended balance of well-timed,

targeted advocacy and technical assistance. In short, the approach to influencing government

policy recommended by many participants was one of discrete, targeted, planned, evidence-

based and measured technical advice, with government seeing the NGO as a constructive

partner not a public critic. Participants from Azerbaijan, Ethiopia and Nepal added that it helps

first to demonstrate the effectiveness of new service models before offering technical advice,

which alone might not be accepted.

7. Maximum impact and sustainability results from a balance of service

delivery, technical assistance and advocacy

The participants from Georgia, Moldova and Azerbaijan stressed that the optimal approach is to

plan and coordinate use of all three strategic approaches in a balanced way, each enhancing the

effectiveness of the others. The participant from Azerbaijan was emphatic that one approach

would not work in isolation from the others

14

.

14

We do all three because in my opinion thats the only way to get anywhere. We have to do the service delivery to build up the

understanding and the awareness and the demand for that service. We have to be expert in that service, to then provide the technical

assistance, which the government needs to be able to in turn take on the service. And then of course you also have to have a long-running

advocacy campaign to build up everyones understanding and awareness and move them to action. Azerbaijan participant, in interview.

Conclusions

How governments differ in their policy and practice

towards NGOs

Some of the patterns in NGO government relationships that this research detected could be

linked to socio-economic context. The most consistent difference was between the governments

of the four former Soviet countries

15

and the others. Despite socio-economic differences

between them

16

, these four governments demonstrated clear intentions to fund NGOs to

deliver services. In the case of Moldova, and to some extent Azerbaijan, this was accompanied by

a willingness to receive technical assistance from specialist NGOs. For those with lower income,

Georgia and Moldova, the commitment to promote cooperation with NGOs could be partly

attributed to donor influence, in particular where a condition of direct budget support was

enabling NGO participation in delivery of services. In Azerbaijan and Russia where donor

influence was much less, governments willingness to work with certain NGOs appeared to

derive more from a recognition of their technical expertise, though participants found this

willingness to be inconsistent and often tempered by indifference or detachment.

In the countries with the lowest levels of GDP per capita, Ghana, Nepal and Zimbabwe but not

Ethiopia, participants experienced government interest in cooperation with NGOs as linked to

opportunities access to donor funds. However, their limited budgets meant these governments

also had weaker capacity to fund or contract NGOs, and to monitor and regulate relations with

NGOs.

How NGOs make strategic choices and plans in response

to government policy and practice

The NGOs studied had adopted a wide variety of strategic approaches and tactics, with different

combinations of service delivery, advocacy and technical assistance. However, when asked about

the future strategic direction of their NGO, in response to the legal and policy environment, all

except the participant from Zimbabwe

17

showed some interest in a greater focus on technical

assistance.

A second finding was that all the NGOs, with the exception of Ethiopia, could still see some role,

or an increasing role for advocacy in their strategic approach as a means to influence government

15

Azerbaijan, Georgia, Moldova, and Russia.

16

Within the former Soviet states, there are considerable differences in GDP and UN measures of human development which divide

them into two groups Russia and Azerbaijan, with higher levels of income and development but lower scores on measures of civil society,

perceptions of corruption (an indicator of strength of governance and rule of law) and accountability and public voice (as measured by

the Freedom House index); as compared with Georgia and Moldova, with weaker socio-economic indicators but stronger in terms of the

measures of civil society, control of corruption and accountability.

17

Zimbabwes case could be explained by its high level of political uncertainty, with the participant foreseeing the next few months, with a

scheduled constitutional referendum and presidential elections, as crucial for determining the future environment for government NGO

cooperation.

policy, legislation and practice so as to achieve wider more sustainable benefits for stakeholders

than could be achieved through NGOs simply providing services. Even those NGOs that

described their main focus as technical assistance or service delivery still saw these activities as

means to an end rather than an end in itself, the end being achieving positive change at national

level. However, for those with governments sensitive to public criticism, these long term goals

were seen as more likely to be achieved through quiet partnership than public advocacy.

A third set of findings relate to common practices adopted by NGOs to ensure they were taken

seriously by government, and trusted by the public, including: promoting and complying with

strong regulation and monitoring of NGOs; joining together to form alliances to enhance their

voice and credibility, and presenting clear evidence for policy and practice recommendations

from participatory research or evaluations of new services.

A fourth set of findings was the most common criteria for successful NGO government

cooperation, which included: building strong, trusting relationships with individuals and certain

departments in government; developing cooperation based on shared interests with key

government counterparts, and effectively coordinating with donor spending plans. However,

participants also warned that conspicuous alignment with donors, especially when government

are suspicious of the agenda of donor governments, can undermine NGOs perceived credibility

and independence and their claims primarily to speak and act for on and behalf of local

communities and vulnerable groups. This reinforces the need for NGOs to maintain high levels

of transparency, accountability and representativeness in order to retain the public trust and

credibility they need for their work to be valued and effective.

Finally, the research highlighted that national NGOs face unique and often unexpected

challenges as they engage with governments in varied and changing political and legal

environments. Often the reported experiences of NGO staff contradicted what would be

predicted from published reports and indicators from their country. The largely positive accounts

of the participant from Azerbaijan were not what would have been predicted from the countrys

low ranking on measures of civil society and freedom of association

18

, while the participants from

Ghana and Georgia only voiced negative perceptions of recent change, in contrast to reports

showing a generally positive government approach towards civil society in these countries.

19

The

way NGOs approach relations with government, how they experience the overall direction of

change in their country, and the way this in turn influences their strategic planning, therefore

appears to be as much the result of individual perception and expectations, and personal

relationships and connections, as the broader social, economic or political factors described in

published data and reports.

18

Sattarov et al, 2007, and Freedom House, 2012, Nations in Transit report http://www.freedomhouse.org/report/nations-

transit/2012/azerbaijan

19

Darkwa et al (2006) and Losaberidze (2010).

References

Darkwa, A., Amponsah, N. and Gyampoh, E (2006): Civil Society in a Changing Ghana: An Assessment of the Current State of Civil Society

in Ghana. CIVICUS Civil Society Index Report for Ghana, with Support from the World Bank. Coordinated in Ghana by GAPVOD.

Economist (1999): Non-governmental Order: Will NGOs Democratise, or Merely Disrupt, Global Governance? 1117 December.

http://www.economist.com/node/266250

Fioramonti, L. and Heinrich, V. F. (2007): How Civil Society Influences Policy: A Comparative Analysis of the CIVICUS Civil Society Index in

Post-Communist Europe. CIVICUS Research Report commissioned by: Research and Policy in Development (RAPID), Overseas

Development Institute (ODI).

Heinrich, V.F. (ed.) 2007, Civicus Global Survey of the State of Civil Society, Volume 1 Country Profiles, vol. 1, Kumarian Press, Bloomfield

Conn.

ICNL (2009): Global Trends in NGO Law Volume 1, Issue 1. International Center for Not-for-Profit Law.

http://www.icnl.org/research/trends/trends1-1.html

ICNL (2012): International Centre for Not for Profit Law http://www.icnl.org/research/monitor/russia.pdf

Losaberidze, D (2010): An Assessment of Georgian Civil Society - Report of the CIVICUS Civil Society Index, Caucasus Institute for Peace,

Democracy and Development (CIPDD), Tbilisi.

Lyons, M (2009): Measuring and Comparing Civil Societies. Cosmopolitan Civil Societies Journal, Vol.1, No.1.

Najam, A (2000): The Four-Cs of Third Sector Government Relations: Cooperation, Confrontation, Complementarity and Co-optation.

Nonprofit Management and Leadership 10(4): pp 375-97.

Salamon, L.M. & Sokolowski, S.W. (2004), Measuring Civil Society: the Johns Hopkins Global Civil Society Index, in L.M. Salamon, S.W.

Sokolowski & Associates (eds), Global Civil Society: Dimensions of the Nonprofit Sector, Volume 2, Kumarian Press, Bloomfield Conn.

Salamon, L.M., Sokolowski, S.W. and List, R (2003): GLOBAL CIVIL SOCIETY: An Overview. The Johns Hopkins Comparative Nonprofit

Sector Project. The Johns Hopkins University Center for Civil Society Studies. Baltimore, MD

Sattarov, R., Faradov, T., and Mamed-zade, I: (2007) Civil Society in Azerbaijan: Challenges And Opportunities in Transition. CIVICUS Civil

Society Index Report for Azerbaijan. International Center for Social Research.

Вам также может понравиться

- A Winning Team? The Impacts of Volunteers in SportДокумент70 страницA Winning Team? The Impacts of Volunteers in SportNCVO100% (2)

- Health Check: A Practical Guide To Assessing The Impact of Volunteering in The NHSДокумент36 страницHealth Check: A Practical Guide To Assessing The Impact of Volunteering in The NHSNCVOОценок пока нет

- LSF Project Case Study: WENДокумент1 страницаLSF Project Case Study: WENNCVOОценок пока нет

- LSF Project Case Study: Organisation GДокумент12 страницLSF Project Case Study: Organisation GNCVOОценок пока нет

- LSF Project Case Study: Organisation EДокумент17 страницLSF Project Case Study: Organisation ENCVOОценок пока нет

- LSF Project Case Study: Organisation FДокумент10 страницLSF Project Case Study: Organisation FNCVOОценок пока нет

- LSF Project Case Study: LGTДокумент1 страницаLSF Project Case Study: LGTNCVOОценок пока нет

- LSF Project: Final ReportДокумент98 страницLSF Project: Final ReportNCVO100% (2)

- LSF Project: NCVO CES Evaluation of Learning StrandДокумент17 страницLSF Project: NCVO CES Evaluation of Learning StrandNCVOОценок пока нет

- LSF Project Case Study: Organisation BДокумент12 страницLSF Project Case Study: Organisation BNCVOОценок пока нет

- LSF Project Case Study: Organisation DДокумент12 страницLSF Project Case Study: Organisation DNCVOОценок пока нет

- LSF Project Case Study: Organisation CДокумент17 страницLSF Project Case Study: Organisation CNCVOОценок пока нет

- LSF Project Case Study: Hoot Creative ArtsДокумент1 страницаLSF Project Case Study: Hoot Creative ArtsNCVOОценок пока нет

- LSF Project Case Study: Organisation HДокумент10 страницLSF Project Case Study: Organisation HNCVOОценок пока нет

- LSF Project Case Study: Access2BusinessДокумент1 страницаLSF Project Case Study: Access2BusinessNCVOОценок пока нет

- LSF Project Case Study: Age UK DacorumДокумент1 страницаLSF Project Case Study: Age UK DacorumNCVOОценок пока нет

- LSF Project Case Study: CAST North WestДокумент1 страницаLSF Project Case Study: CAST North WestNCVOОценок пока нет

- LSF Project Case Study: Four Corners FilmДокумент1 страницаLSF Project Case Study: Four Corners FilmNCVOОценок пока нет

- LSF Project Case Study: Action East DevonДокумент1 страницаLSF Project Case Study: Action East DevonNCVOОценок пока нет

- LSF Project Bulletin: Peer-To-peer Visits (August 2017)Документ7 страницLSF Project Bulletin: Peer-To-peer Visits (August 2017)NCVOОценок пока нет

- LSF Project Bulletin: Needs Analysis and Thematic Mapping Report (November 2016)Документ27 страницLSF Project Bulletin: Needs Analysis and Thematic Mapping Report (November 2016)NCVOОценок пока нет

- LSF Project Bulletin: Analysis of Pre and Post ODT Scores (October 2017)Документ22 страницыLSF Project Bulletin: Analysis of Pre and Post ODT Scores (October 2017)NCVOОценок пока нет

- LSF Project Bulletin: Understanding Grant Holders and Their LSF Projects (June 2017)Документ4 страницыLSF Project Bulletin: Understanding Grant Holders and Their LSF Projects (June 2017)NCVOОценок пока нет

- LSF Project Bulletin: Journeys Start-Up (November 2016)Документ3 страницыLSF Project Bulletin: Journeys Start-Up (November 2016)NCVOОценок пока нет

- LSF Project Bulletin: Analysis of End of Year Monitoring Reports (September 2017)Документ12 страницLSF Project Bulletin: Analysis of End of Year Monitoring Reports (September 2017)NCVOОценок пока нет

- LSF Project Bulletin: Six Monthly Monitoring Reports (March 2017)Документ6 страницLSF Project Bulletin: Six Monthly Monitoring Reports (March 2017)NCVOОценок пока нет

- LSF Project Bulletin: Learn and Share Events (March 2017)Документ6 страницLSF Project Bulletin: Learn and Share Events (March 2017)NCVOОценок пока нет

- LSF Project Bulletin: Results of Snapshot Survey 3 (July 2017)Документ8 страницLSF Project Bulletin: Results of Snapshot Survey 3 (July 2017)NCVOОценок пока нет

- LSF Project Bulletin: Results of Snapshot Survey 2 (February 2017)Документ4 страницыLSF Project Bulletin: Results of Snapshot Survey 2 (February 2017)NCVOОценок пока нет

- LSF Project Bulletin: Results of Snapshot Survey 1 (October 2016)Документ5 страницLSF Project Bulletin: Results of Snapshot Survey 1 (October 2016)NCVOОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- MS Development Studies Fall 2022Документ1 страницаMS Development Studies Fall 2022Kabeer QureshiОценок пока нет

- 04-22-14 EditionДокумент28 страниц04-22-14 EditionSan Mateo Daily JournalОценок пока нет

- Benefit Incidence AnalysisДокумент1 страницаBenefit Incidence Analysischocoholickronis6380Оценок пока нет

- LJGWCMFall 23Документ22 страницыLJGWCMFall 23diwakarОценок пока нет

- Motions Cheat Sheet Senior MUNДокумент2 страницыMotions Cheat Sheet Senior MUNEfeGündönerОценок пока нет

- Personal Laws IIДокумент12 страницPersonal Laws IIAtulОценок пока нет

- Site Selection: Pond ConstructionДокумент12 страницSite Selection: Pond Constructionshuvatheduva123123123Оценок пока нет

- Buscayno v. Military Commission PDFДокумент18 страницBuscayno v. Military Commission PDFTori PeigeОценок пока нет

- LARR 45-3 Final-1Документ296 страницLARR 45-3 Final-1tracylynnedОценок пока нет

- Letter To Erie County Executive Kathy Dahlkemper From Erie County Councilman Kyle FoustДокумент2 страницыLetter To Erie County Executive Kathy Dahlkemper From Erie County Councilman Kyle FoustMattMartinОценок пока нет

- Urban Stormwater Bmps - Preliminary Study - 1999 PDFДокумент214 страницUrban Stormwater Bmps - Preliminary Study - 1999 PDFAnonymous lVbhvJfОценок пока нет

- Comparison Between Formal Constraints and Informal ConstraintsДокумент4 страницыComparison Between Formal Constraints and Informal ConstraintsUmairОценок пока нет

- Sexual HarrassmentДокумент6 страницSexual HarrassmentKristine GozumОценок пока нет

- 123 Agreement W RussiaДокумент7 страниц123 Agreement W Russiafremen12Оценок пока нет

- Inter Protection of Human RightsДокумент103 страницыInter Protection of Human RightsMERCY LAWОценок пока нет

- CW3 - 3Документ2 страницыCW3 - 3Rigel Zabate54% (13)

- AP District Office Manual in TeluguДокумент3 страницыAP District Office Manual in Teluguykr81.official100% (1)

- Council of Red Men Vs Veteran ArmyДокумент2 страницыCouncil of Red Men Vs Veteran ArmyCarmel LouiseОценок пока нет

- Elective Local Official'S Personal Data Sheet: PictureДокумент2 страницыElective Local Official'S Personal Data Sheet: PictureMarie Alejo100% (1)

- Intro For Atty. Jubil S Surmieda, Comelec - NCRДокумент2 страницыIntro For Atty. Jubil S Surmieda, Comelec - NCRChery Lyn CalumpitaОценок пока нет

- Get your voter's certification onlineДокумент1 страницаGet your voter's certification onlineBarie ArnorolОценок пока нет

- Resolved: Unilateral Military Force by The United States Is Not Justified To Prevent Nuclear Proliferation (PRO - Tritium)Документ2 страницыResolved: Unilateral Military Force by The United States Is Not Justified To Prevent Nuclear Proliferation (PRO - Tritium)Ann GnaОценок пока нет

- The Presidency of John AdamsДокумент6 страницThe Presidency of John Adamsbabyu1Оценок пока нет

- Section 15 - Versailles To Berlin - Diplomacy in Europe PPДокумент2 страницыSection 15 - Versailles To Berlin - Diplomacy in Europe PPNour HamdanОценок пока нет

- Everywhere But Always Somewhere: Critical Geographies of The Global SouthereДокумент15 страницEverywhere But Always Somewhere: Critical Geographies of The Global SouthereKevin FunkОценок пока нет

- Program On 1staugustДокумент3 страницыProgram On 1staugustDebaditya SanyalОценок пока нет

- Command History 1968 Volume IIДокумент560 страницCommand History 1968 Volume IIRobert ValeОценок пока нет

- The #MeToo Movement's Global ImpactДокумент2 страницыThe #MeToo Movement's Global ImpactvaleriaОценок пока нет

- Unit 1 (1.5)Документ5 страницUnit 1 (1.5)Niraj PandeyОценок пока нет

- ISBN9871271221125 'English VersionДокумент109 страницISBN9871271221125 'English VersionSocial PhenomenaОценок пока нет