Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Tax Increment Financing and Education Expenditures: The Case of Iowa

Загружено:

nguyenhphuongОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Tax Increment Financing and Education Expenditures: The Case of Iowa

Загружено:

nguyenhphuongАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Tax Increment Financing and Education Expenditures:

The Case of Iowa

Author: Phuong Nguyen-Hoang, Assistant Professor at the School of Urban and Regional

Planning, and Public Policy Center, University of Iowa

Postal address: 344 Jessup Hall, Iowa City, IA 52242

Email: phuong-nguyen@uiowa.edu

Phone: 319-335-0034

Abstract: This is the first study to directly examine the relationship between tax increment

financing (TIF) and education expenditures, using the state of Iowa as a case study. I find that

greater use of TIF is associated with reduced education expenditures. I also find little evidence to

support the commonly held proposition that school spending increases when TIF districts expire.

Finally, the negative price effect of TIF on education spending is increasingly larger for school

districts in lower wealth or income groups compared to their peers in higher wealth or income

groups. The negative, though small, effect of TIF on education spending, coupled with no gain

from the often-claimed long-run benefits of TIF, justifies policy measures to protect school

districts from TIF.

This paper is a pre-print version and it has been accepted for publication in Education

Finance and Policy, vol. 39, issue 4.

1

<A>Introduction

Tax increment financing (TIF) has become an increasingly popular economic

development tool in the United States since its first use in California in 1952.

1

As of 2013, only

Arizona has not enacted TIF legislation.

2

In recent years, TIF has been a hot-button issue in

Iowathe state of focus in this paper. In 2011, there were more than 2,200 TIF districts in Iowa.

Nearly 86 percent (or 297) of the school districts in the state contained one or more TIF districts

in at least one year during the sample period between 2001 and 2011. These 297 school districts

with TIF districts accounted for 96 percent of state total enrollment in 2011.

Two major reports (Fisher 2011; Fisher and Lipsman 2012) detail how TIF in Johnson

and Polk counties in Iowa has been abused, with consequences for overlapping jurisdictions

including school districts. For one, the merged Iowa River Landing/Coral Ridge Mall Urban

Renewal Area in Johnson County diverted $4.99 million in property taxes from the Clear Creek

Amana and Iowa City Community school districts, leading them to increase property tax rates by

$2.83 and $0.56 per $1,000 of taxable value, respectively.

To use TIF, municipal and county governments establish a TIF district and are then

allowed to divert the additional property taxes (associated with increased property values in the

district) as TIF funds to defray development-related costs. In the absence of TIF, the additional

property taxes would have been accessible to other overlapping jurisdictions, such as school

districts and counties. Indeed, one of the key issues in using TIF is how it may affect overlapping

jurisdictions, especially school districts and their spending. However, as reviewed later in this

paper, most studies on TIF focus on issues other than education finance. A few of them, such as

Lehnen and Johnson (2001) and Weber (2003), examine the impact of TIF on school district

1

TIF is also less commonly known as a Tax Allocation District (TAD) as in Georgia, Revenue Allocation

District (RAD) as in New Jersey, or Tax Increment Reinvestment Zone (TIRZ) as in Texas.

2

Californiaas noted, the first state to enact TIF legislationrepealed its TIF law in February 2012.

2

finances, particularly school district property tax revenues. No study has directly examined the

relationship between TIF and education expenditures. This paper aims to fill this gap in the

literature. Given the widespread use of TIF in Iowa and potentially sizeable fiscal impacts on

school districts, the empirical findings from this paper have implications for TIF policy in Iowa

and other states.

How might TIF affect education expenditures? In many cases, TIF freezes the property

tax base at a level below what it would be without TIF, and lower property wealth is likely to

reduce the amount of money local taxpayers are willing to pay for education. This mechanism

can be explained using a demand, or tax price, mechanism (tax price is defined as the share of a

voters house value to the districts tax base measured by total per pupil taxable property value).

TIF proponents often claim that voters in a school district with a TIF project have lower tax

prices of, and thus higher demand for, education expenditures than in the absence of TIF. Tax

prices may be lower from a larger property tax base after the TIF project comes to an end, and/or

when the TIF project is designated to a blighted area with properties that would have depreciated

in value without TIF. The voters would enjoy a larger tax base and demand more education

services when the TIF project produces positive spillover effects on neighboring properties.

Opponents, however, argue that TIF may increase voters tax prices of education spending and

thus lower their demand for it. Higher tax prices occur when cities adopt TIF for areas rich in

properties that would have trended upward in value, even without TIF, and/or when TIF

negatively affects the value of neighboring non-TIF properties within the school district.

I use panel data on Iowa school districts between 2001 and 2011 to answer four

interrelated research questions: (1) How are education expenditures generally affected by TIF

use? (2) Are there differential effects from different types of TIF properties on education

3

spending? (3) Does education spending increase when TIF districts expire? and (4) Does TIF

affect the spending of school districts in different wealth or income groups differently? To

preview, I find that heavier use of TIF is associated with decreased school district spending,

holding all other factors constant. Also, residential and industrial TIF properties (but not

commercial TIF properties) have significant negative effects on school district spending. I find

little evidence of increased education expenditures once TIF districts expire. Finally, the lower a

school districts wealth, the more TIF negatively affects education spending.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. The next section presents background on

TIF use in Iowa, a review of TIF-related literature, and basic information on school finance in

the state. I then present a theoretical framework on how TIF might affect school expenditures,

followed by a section that elaborates on my empirical strategy. I then discuss empirical results,

and conclude with policy implications and suggestions for future research.

<A>Background

<B>How TIF Works and TIF in Iowa

TIF is a financing tool used by local governments, mostly cities and counties, to fund a

project to address blight or promote economic development. Although some TIF programs are

based on sales and income taxes (Smith 2009), property tax increment financing is used in most

states with TIF-enabling legislation, including Iowa.

3

A TIF project in Iowa begins when a

municipality designates an urban renewal area with clearly defined boundaries as a TIF district

3

The only example of a sales taxbased TIF district in the state is the Iowa Speedway Project in Newton

(approved in 2005).

4

or area.

4

The TIF district is governed by an authority empowered to enter into contractual

agreements and sell debt backed by TIF revenue.

Once established, the city freezes the assessed value of all taxable property within the

TIF district at the base yearthe year immediately prior to when the TIF district becomes

effective. During the subsequent life span of the TIF project, the increase in assessed value above

the base value is the incremental value. Tax increment thus refers to tax revenues generated on

this incremental value by all overlapping taxing jurisdictions, namely, the city, school districts,

counties, and other special-purpose districts. The TIF governing authority uses this tax increment

to finance development (via bond issuance or on a pay-as-you-go basis), while property tax

receipts from the frozen tax base continue to be channeled to the corresponding overlapping

jurisdictions. All of the incremental value that may have built up over the years becomes

accessible to these overlapping jurisdictions upon expiration of the TIF project.

TIF in Iowa is authorized by the Urban Renewal Law (Iowa Code, Chapter 403). This

law, enacted in 1957, allowed municipalities to use TIF only in slum or blighted areas.

5

(Whether

a TIF district is blighted and whether it cannot be redeveloped through regular private enterprise

but for the TIF incentive, also known as the but for test, are two common considerations for

TIF approval.) A legal amendment in the 1985 Iowa Acts (Chapter 66) puts Iowa among a few

states that do not currently require the presence of slum or blight conditions for TIF adoption.

This amendment suggests that cities in Iowa are allowed, and would probably prefer, to adopt

TIF for non-blighted areas, enabling them to capture a portion of the incremental value that

would have been available to overlapping jurisdictions.

4

A TIF district in Iowa can encompass an entire urban renewal area. Alternatively, multiple TIF districts

can be contained in a single urban renewal area (Cory and Martin 2012). For simplicity, I interchangeably

use TIF districts or areas in this paper.

5

Under Chapter 403, blight was defined as an economic and social liability imposing onerous municipal

burdens which decrease the tax base and reduce tax revenues.

5

The Urban Renewal Law has had additional important amendments over the years. For

one, counties in Iowa were authorized to use TIF only for industrial purposes (1991 Iowa Acts,

Chapter 214).

6

TIF can also be used for development of affordable housing for low- and

moderate-income people (1996 Iowa Acts, Chapter 1204). Since 1996, public hearings have been

legally required for the initial approval of an urban renewal plan, although not for each TIF

district that is established under the plan (1996 Iowa Acts, Chapter 1047). However, overlapping

jurisdictions are still unable to opt out of the establishment of a renewal area or TIF district.

These legal amendments led to a soaring increase in the number of TIF districts in Iowa.

In 1989, there were approximately 185 TIF districts in Iowa, most of which were based on the

blight requirement in the pre-1985 law (Talanker and Davis 2003). By 1999, the number of TIF

districts statewide had increased to 2,496 (Swenson and Eathington 2002), before decreasing to

2,125 in 2011 (Robinson 2011). Iowa cities and counties use TIF at rates comparable with other

Rust Belt states such as Wisconsin and Illinois (Briffault 2010).

Iowa school districts subject to TIF vary significantly in terms of the number of TIF

districts within their jurisdictions. The Davenport School District had the greatest number, with

fifty-nine TIF districts in 2011. As shown in the first panel of Table 1, it has become more

common for school districts to contain a large number of TIF districts. For example, from 2001

to 2011, there was a six-fold increase in the number of school districts each containing at least 30

TIF districts. The second panel of Table 1 shows that school districts are now less likely to have

TIF districts in their jurisdictions expire. For example, 128 school districts had TIF districts

expire from 2001 to 2003, compared to the period 2009 to 2011 when only 29 school districts

had TIFs expire. The third panel of Table 1 shows fewer school districts experiencing new TIF

6

Among local governments in Iowa, municipalities are still the primary recipients of TIF revenues. In

fiscal year 2011, 40 out of 99 counties and 349 out of 947 incorporated cities received TIF revenues

(Robinson 2011).

6

districts over time. School districts with new TIF districts still outnumbered those with expired

TIF districts in all the years during the sample period.

<B>Related Literature

Studies on TIF appeared in academic journals as early as the late 1970s (Davidson 1978).

This now substantial body of literature has revolved around key issues. For one, scholars have

sought to identify the factors that drive municipalities to adopt TIF. Population size,

intergovernmental aid, industrial composition, fiscal pressure, and tax competitionbut not

blightare associated with the likelihood of municipal TIF adoption (Anderson 1990; Dye and

Sundberg 1998; Man and Rosentraub 1998; Man 1999; Byrne 2005). Another key issue is how

TIF adoption can affect the values of property within TIF districts and have spillover effects on

property outside TIF districts. While Byrne (2006) examines factors influencing property value

growth within TIF districts, Smith (2006) finds that properties in TIF districts exhibit higher

rates of appreciation than those outside TIF districts, and higher rates than prior to TIF

designation. Weber, Bhatta, and Merriman (2003) find that improved industrial TIF parcels

appreciate at the same rate as otherwise identical industrial non-TIF parcels.

Several studies explicitly examine TIF spillover effects on property in non-TIF areas.

Bossard (2011) finds evidence of nonlinear TIF spillover effects on the growth of non-TIF

property values in school districts. Several studies find negative spillovers from TIF use. Dye

and Merriman (2000) show that the non-TIF portions of Illinois municipalities with TIF districts

have slower real value growth than communities without TIF. Dye and Merrimans (2003)

subsequent finding that TIF adoption has no impact on the growth of citywide property values

suggests that value growth in TIF districts is offset by declines in non-TIF areas in the adopting

city. Specifically, commercial and industrial TIF districts hinder the growth of commercial non-

7

TIF property values. Weber, Bhatta, and Merriman (2007) also find that residential houses

adjacent to commercial and industrial TIF districts see decreases in appreciation rates, and they

argue that industrial TIF districts produce negative spillovers through development that is noisy,

polluting, aesthetically unappealing, and, like commercial development, conflicts with residential

land uses (p. 279). These authors also posit that negative spillover to residential neighborhoods

from commercial TIF districts might result from traffic congestion and the lack of pedestrian

access around the big-box retail stores typically found in commercial TIF districts. By contrast,

Merriman, Skidmore, and Kashian (2011) find positive, though not precisely estimated,

stimulatory effects of commercial TIF on commercial activity in non-TIF areas.

Three studies examine the effects of TIF on school revenues. Lehnen and Johnson (2001)

find that TIF is not a revenue drain for school districts in Indiana because TIF was not intensely

adopted in 1995the only year with data available. Weber (2003) finds an inverse relationship

between TIF intensity and property tax revenues across school districts in Cook County, Illinois.

However, Weber, Hendrick, and Thompson (2008) find little effect of TIF on school revenues

when they extend the sample to include all districts in Illinois.

A few studies focus on TIF in Iowa, in addition to the two Fisher reports cited earlier.

Nydle (2009) and Perri (2001) examine legal aspects of TIF in Iowa. Lawrence and Stephenson

(1995) develop a model to determine which Iowa taxpayers under which taxing authorities fund

TIF expenditures and receive subsidies from TIF programs. Pacewicz (2013) looks at the role of

TIF in the financialization of urban politics in two cities in Iowa. Swenson and Eathington (2002,

2006) examine the growth of TIF in Iowa and how it might impact economic development in

Iowa cities. This study is the first to examine directly how TIF affects education expenditures.

8

<B>School Finance in Iowa

School districts in Iowa, as in other states, are financed primarily by property taxes and

state aid. Iowa adopts a foundation aid formula. The foundation level is equal to 87.5 percent of

state cost per pupil, as determined by the previous years state cost per pupil plus the regular

allowable growth (usually 1 to 4 percent) set annually by the states General Assembly. All

districts contribute to the foundation level with property taxes at a uniform (statewide) rate of

$5.40 per $1,000 of assessed valuation available to school districts (that is, the incremental value

of TIF areas is excluded). The state provides aid for the difference between the foundation level

and this uniform levy (or, the required local contribution). Under this formula, state aid per pupil

is smaller for property-rich than for property-poor districts. Beyond this foundation level,

districts can use an additional levy to meet district costs per pupil, as derived by their previous

year district cost per pupil plus the state-determined regular allowable growth. Since the

maximum district cost per pupil can be no more than 105 percent of the state cost per pupil,

district costs per pupil vary minimally across districts.

Little variation in district costs per pupil does not necessarily mean little variation in

actual expenditures. As indicated in Table 2, after adjusting for inflation, total operating

expenditures per pupil vary substantially, with a standard deviation of nearly $3,000. The

maximum spending was nearly eight times as much as the minimum spending. This substantial

variation results from different expenditure ceilings that are determined by districts total

spending authority. Spending authority for any given year comprises the total district cost,

miscellaneous income, and unspent spending authority, which is the difference between the

districts total spending authority and actual expenditures in the previous year.

9

The catchall term of miscellaneous income includes any income a school district

receives other than the uniform and additional levies and state foundation aid. Examples include

investment interest, fees for student services, income surtaxes, federal aid, state grants, and funds

raised for educational programs such as instructional support programs (ISP) and educational

improvement programs (EIP).

7

Specifically, funds for the ISP and EIP can be increased up to 10

and 5 percent of the district cost, respectively. These additional funds for ISP or EIP can come

from property taxes exclusively, or from a combination of property taxes and revenues from an

income surtax that is charged as a percent of an individuals state income tax liability.

8

Notably,

some property tax levies are not subject to TIF funds captured by cities or counties. Property tax

levies in this category are those for debt service and for physical plant and equipment (PPEL).

Therefore, my empirical work focuses only on the effects of TIF on operating expenditures.

<A>Theoretical Framework

How TIF might affect education expenditures can be examined in terms of how TIF

might affect demand for education services. Demand for publicly provided education services

depends on factors such as local residents income, demographic characteristics representing

differential preferences for education, and the price of education services. Of these factors, TIF

most plausibly affects the demand for education services through the price that voters have to

pay for additional education spending. As education is a publicly provided normal good, the

higher the price, the lower the demand for education spending, and vice versa. This section

presents a theoretical framework for potential effects of TIF on education spending by

7

The property tax levy for instructional support programs is not available for TIF use if TIF debt incurs

after April 24, 2012, which post-dates the last year of my sample period. Also, funds for both of these

programs are included in a school districts operating funds.

8

Iowa is among a few states (including Kentucky, Ohio, and Pennsylvania) that authorize school districts

to levy local income taxes for specific education programs (Ross and Nguyen-Hoang 2013).

10

comparing a voters tax liability or price (and thus his/her demand for education spending) in the

presence and absence of TIF.

The tax liability, , of a voter in a school district is determined by school district tax rate,

, and this voters taxable property value, , or

(1)

This district has a budget constraint represented by equation (2)

, (2)

where E is total operating expenditures per pupil;

is total taxable property value per pupil; is

total state aid per pupil; and is other revenues per pupil such as income surtaxes and federal

aid. As discussed above, state education aid per pupil (A) is distributed to make up the difference

between the foundation level () equal to 87.5 percent of state district cost per pupil, and local

contributions equal to the product of the uniform property tax rate (

) of 0.0054 and total

taxable property value per pupil (

). Equation (2) can be rewritten as equation (3):

(

(3)

In a typical school districts annual budget process, the district calculates per pupil

property tax revenues that need to be raised () by subtracting F and O from E. As the final step

to establish how much the district will spend (Mikesell 2014, p. 495), the property tax rate, , is

set by equation (4):

(4)

The first term of (4),

, gives an additional tax rate that the district needs to levy on

local residents in addition to the uniform rate,

.

9

Substituting (4) into (1) yields

9

Total school district property tax rates were always higher than the uniform rate during the sample

period, ranging between $8.168 and $24.426 per $1,000 assessed valuation.

11

(

(5)

I now incorporate the potential effects of TIF into equation (5). Of the factors in this

equation, TIF is mostly likely to affect

, which is negatively correlated with the voters tax

liability, . Let us take a closer look at how this might happen.

10

I can divide the school district

into two areas: the TIF and non-TIF (N) areas. While the non-TIF area has its own taxable

property values per pupil (

), the TIF area has two separate taxable property values per pupil:

frozen value (

) and incremental value (

). The frozen value,

, is set by freezing the previous

years values of the properties within the TIF district, called the base value (

). While

produces additional revenue that, rather than being channeled to the school district, is captured

by the initiating city or county to finance TIF activities, the school district is still entitled to

and

, or

.

11

Assuming that there is no spillover effect of TIF on non-TIF areas (or on

), I focus first

on how

and thus

might be smaller or larger with TIF than without TIF. One of two common

10

Potential effects of TIF on education expenditures can be explained through a budgeting mechanism.

This mechanism also examines how TIF might affect

. Unlike the demand mechanism, the effects of

TIF on education spending E are captured in the first term on the right-hand side in equation (2),

. The

budgeting mechanism is less appropriate for this study. While TIF might change

, the final link between

TIF and E depends crucially on whether school districts can set the tax rate, , at will. If they can do so,

the effects of TIF on E are then confounded and harder to untangle. The budgeting mechanism would be

more appropriate in a state with limits on property tax rates levied by school districts (as in California

with Proposition 13). This is not the case for Iowa, where school districts are not subject to state-imposed

cap limits on property tax rates.

11

While a districts assessed value that is used to compute its required contribution in Iowas state

education aid formula is based only on non-TIF areas, or

), other states may calculate the local

contributions based on the total local property tax base, regardless of whether it is available to the school

district; that is,

). Working this contribution formula through equations (2)(4), a voters

tax liability in those states equals ((

). All else being equal, a marginal increase in

, a

key measure of TIF use, raises the tax liability of a voter (via

) more in those states than in Iowa,

which suggests that the marginal effect on education expenditures of TIF, especially in cases of higher tax

price and thus lower spending demand, is highly likely to be larger in those states than in Iowa.

12

scenarios may occur, depending on the underlying trend (or growth rate) of the base value,

.

12

The first scenario illustrated by Figure 1 occurs when

has a positive (upward) underlying

trend (i.e., the property tax base of the TIF district is poised to increase even without TIF). The

frozen value,

, is lower than what

would have been in the absence of TIF. Put differently,

the voter has higher annual tax liabilities and lower annual demand for education spending

during the TIF period than he or she would have had without TIF. A portion of

captures the

difference between

and

that would otherwise have been accessible to the school district.

TIF adoptions for areas rich in appreciating property benefit cities but fiscally constrain

overlapping jurisdictions including school districts. Opponents often cite this scenario in their

criticisms of TIF. The second scenario happens when a TIF district is established for an area with

declining (or negative-trending) property values. This is usually the case for blighted areas. A

voters tax liability is lower with TIF than in the absence of TIF because

would have been

lower than the frozen value,

. This is the best scenario in which local residents, all else being

equal, benefit from lower tax liabilities, thereby probably increasing their demand for education

spending.

13

Three points are worth mentioning. First, either scenario 1 or 2 may occur when

as in Figure 1, that is, when the values of properties within TIF districts have a higher rate of

appreciation than those of similar properties outside TIF districts (as in the case of Smiths

[2006] finding). Second, scenario 1 may even occur when the values of TIF properties trend

12

The term underlying indicates that the growth trend of

that is observed prior to TIF adoption would

have continued in later years in the absence of TIF.

during a TIF period is a counterfactual as

illustrated in Figure 1.

13

The third and less likely scenario occurs when

has a zero growth rate (i.e.,

during the TIF period

would have been equal to

). Any increase in

can be attributed completely to TIF. The voters tax

liability with TIF is equal to that without TIF; TIF thus has no effect.

13

upward at the same rate as those of comparable non-TIF properties (as found in Weber, Bhatta,

and Merriman [2003] for improved industrial TIF parcels in Chicago).

I now relax the assumption of no spillover. As evidenced in the literature discussed

earlier, the adoption of TIF may generate spillover effects on property near TIF districts. In other

words,

can be a function of

. The value of

is larger or smaller with TIF than it would

have been without TIF, when

has positive or negative spillover effects, respectively. Together

with the discussions in the preceding paragraph, this observation suggests that a voters demand

for education spending is lower (higher) as a result of his higher (lower) tax liability with TIF

than without TIF when

has negative (positive) spillover effects, and/or when

has a positive

(negative) underlying growth rate.

14

It is thus difficult to accurately predict whether the

relationship between TIF and Iowa school districts education expenditures is neutral, positive,

or negative. Instead, the data can inform us about this relationship.

The earlier review of the TIF literature also suggests that the spillover effects from TIF

may vary depending on the type of TIF district (i.e., commercial, industrial, residential). Put

differently, the size of the spillover effects and thus of the demand for education spending

(holding everything else constant) may vary depending on type of TIF property. The second

research question is intended to explore these potentially differential effects of different TIF

property types.

The above discussions apply to TIF districts during their life spans. When a TIF district

expires, its incremental value (

) in the immediately preceding year (or year

t1

) becomes

accessible to the school district in the current year, making its

with TIF larger than what it

14

For cases in which

has positive (negative) spillover effects, and

has a positive (negative)

underlying growth rate, whether is higher or lower with TIF than without TIF depends on the size of the

spillover effects relative to the size of the absolute difference between

and what

would have been

without TIF.

14

would have been without TIF.

15

At the expiration of the TIF district, decreases, resulting in a

lower price of education services and thus in higher demand for education spending. This is one

of the major arguments for TIF. The third research question is motivated by this argument for the

potential effects of expired TIF districts.

TIF cities would prefer areas with appreciating properties (scenario 1) to blighted areas

with depreciating properties (scenario 2). Only with these TIF areas would they be able to

capture the portion of property tax increases that otherwise would have been available to

overlapping jurisdictions. In other words, cities tend to adopt TIF for purposes other than

addressing blight. Man (1999) finds that Indiana cities under fiscal pressures are more likely to

adopt TIF. Fiscally strained cities are likely to have lower property tax bases, be located in

lower-wealth school districts, and adopt non-blighted TIF areas. Controlling for total numbers of

TIF districts and

, lower-wealth school districts are to have more non-blighted TIF districts,

and thus have a lower demand for education spending, than their higher-wealth peers.

16

I test this

likelihood in the fourth research question.

<A>Empirical Strategy

In keeping with TIF literature, I employ a reduced-form constant-elasticity expenditure

model to estimate the effects of TIF on school district spending.

17

Under this reduced form, I

15

An example of a school districts receiving a sizeable increase in its tax base following an expired TIF

district is Lewis Central School District (LCSD) in Council Bluffs. This school district benefited from

three expired TIF districts in 2003. These three districts had a combined incremental value of over $40.3

million in 2002. This amount became available to LCSD in 2003, dramatically increasing its tax base by

13 percent to about $535.4 million. The 13 percent jump was much higher than the year-on-year increase

of between 5 and 7 percent in the previous three years when none of the TIF districts expired.

16

This likelihood assumes away differences in spillover effects across school district groups. This

assumption is innocuous because there is little reason for such differences.

17

The constant elasticity demand model is dominant in the applied literature on public and education

spending (Duncombe 1996).

15

specify operating expenditures per pupil (E) to be a function of measures related to TIF use (Y),

and a vector of control variables (X) as in equation (6):

, (6)

where i and t index school districts and years. In equation (6), represents district fixed effects

to control for time-invariant district-specific unobserved factors. As adopted in Downes and

Pogue (1994), these district fixed effects also account for time-invariant unobserved efficiency

factors, thereby addressing most of the relative efficiency differences across districts.

18

Year

dummies, , control for common factors affecting all school districts in Iowa in a given year.

Vector X includes all other control variables (unless otherwise specified, all financial

measures are in 2010 dollars and per pupil terms). The first group of control variables includes

characteristics of the student body, such as enrollment, percent of African-American students,

and shares of disadvantaged students, including those receiving free or reduced-price lunch, and

those with Limited English Proficiency (LEP). A higher concentration of disadvantaged students

is expected to induce greater expenditures. Studies reviewed in Fox (1981) and Andrews,

Duncombe, and Yinger (2002) provide empirical evidence that economies of size in education

may help larger districts incur lower costs per pupil. Following this literature, I specify the log of

per pupil expenditures as a quadratic function of the log of enrollment. The second group of

control variables represents voter income (measured by median household income following the

median voter framework of public choice to be discussed), income surtaxes, and

intergovernmental aid (namely, state and federal aid) that school districts receive.

19

Higher voter

18

Studies such as Duncombe and Yinger (2011) may specify efficiency factors that do change over time

as a function of voter income and tax price. However, I use different measures of tax price for vector Y,

and variables indicating voter income are included in vector X of equation (6). For ease of interpretation,

these efficiency effects are disregarded.

19

I do not have data on investment income or student fees. However, they are expected to play a

negligible role in counteracting the use of TIF. Both investment income and student fees traditionally

16

income and additional revenues from income surtaxes or intergovernmental aid are expected to

increase education expenditures.

The third group of variables includes variables representing district-level differences in

demographic characteristics, namely, the share of the population that graduated from four-year

college and the share of owner-occupied housing units. These populations, compared to non-

college graduates and renters, respectively, may have different preferences for school

expenditures. Specifically, college-educated people may desire greater school spending

(Bergstrom, Rubinfeld, and Shapiro 1982; Hilber and Mayer 2009). Since school quality is found

to be capitalized into property values (Nguyen-Hoang and Yinger 2011), homeowners are also

expected to prefer higher education expenditures.

20

<B>Variables of TIF Use

I have two sets of TIF-related measures (Y). I show in the theoretical framework that the

potential effects of TIF on education expenditures revolve mostly around the property tax base,

, and the ratio of

. The first measure in my empirical estimations that captures this ratio is

based on the median voter framework.

21

In this public-choice framework, a school districts level

of spending is the one desired by the majority of its local residents, that is, as chosen by the

median voter. The median voter is decisive; so is his tax price indicating his preference, or

demand, for education. Using Bergstrom and Goodmans (1973) definition, the median voter is

the citizen with a median income who is assumed to own a house of median value. The standard

account for a very small proportion of a school districts operating budget. Also, school districts have

little control over investment receipts primarily determined by market forces.

20

While I log percentage variables indicating student characteristics, I do not log demographic variables

(also in percentage terms). The decision of whether to log percentage variables is to maximize

explanatory power. The main results change little whether all of the percentage variables are logged or

not logged.

21

The median voter framework is just one of the formal public choice voting models. As reviewed in Gill

and Gainous (2002), none of the voting models perfectly describes reality.

17

measure of the price for public services is, therefore, the ratio of median house value to total per

pupil taxable property value accessible to the school district. In this standard measure of tax price

(

), the numerator, , is the median voters. Although

may capture a portion of the effect of

TIF on education spending, it is not a direct indicator of TIF use, and does not allow us to

quantify how much of this effect can be attributed to TIF.

The second set of TIF measures is related more closely to TIF use. The first and key

measure in this set is the incremental taxable property value per pupil in all TIF areas of a school

district in the current year, or

in the theoretical framework.

22

(I naturally log-transform

and

replace undefined logged values (when

) with 0.)

reflects the potential effects of TIF on

. Higher

captures greater absolute differences between

and what

would have been

without TIF (as in the earlier two

-related scenarios), and/or greater spillover effects on

. As

previously discussed, the coefficient of

can be neutral, positive, or negative. A negative

coefficient of

suggests undesirable consequences of TIF on education spending: TIF captures

a portion of the property tax base of the TIF areas that would have increased and been available

to school districts without TIF, and/or makes the property tax base of the non-TIF area smaller

(as a result of negative TIF spillovers) than with no TIF.

Following Merriman, Skidmore, and Kashians (2011) finding that the number of

existing TIF districts within a municipality affects property values, I use a subordinate TIF-

related measure, namely, the number of new TIF districts within a school district (

) in the

current year. This measure might also capture the same potential effects of TIF on

as

. The

coefficients of

and

are thus expected to have the same sign. When both

and

are both

22

For school districts with multiple TIF areas, the estimated coefficient indicates the average effect of all

TIF areas.

18

estimated, the coefficient of

indicates whether an increased concentration of TIF districts has

any effect on educational spending, in addition to the effect from

.

In equation (6),

represents the total incremental value from property of all types. As

discussed earlier, the spillover effects from TIF may vary depending on the type of TIF district,

namely, commercial, industrial, or residential. To investigate potential differential effects from

different types of TIF property on education spending (the second research question), I

disaggregate

into three major types of TIF propertyresidential, commercial, and

industrial

23

and estimate them together with other variables described in equation (6).

A major argument for TIF use is that overlapping jurisdictions, including school districts,

may benefit financially when TIF districts expire, releasing

that has potentially built up over

the years to the overlapping jurisdictions, and thus lowering local voters tax price. To capture

this potential price effect of expired TIF districts (the third research question), I employ the ratio

of the incremental taxable property value to the total taxable property value, both in year

t1

(

),

24

and the number of expired TIF districts within a school district (

).

25

These two

variables are expected to be positively correlated with education expenditures.

To investigate the fourth question as to whether TIF affects the education expenditures

of lower-wealth school districts more than those of higher-wealth districts, I include in equation

(6) an interaction between the main measure of TIF (

), and a variable indicating a school

23

Other property types include agricultural land and buildings, railroads, and utilities with or without gas

and electric property. These properties represented only 2.7 to 4.3 percent of the total incremental value in

TIF districts during the sample period. Also, the data do not have an indicator of TIF type for individual

TIF districts; I am thus unable to disaggregate

or

.

24

This ratio captures the intensity of the TIF use in year

t1

. I use this measure instead of the incremental

taxable property value per pupil in the preceding year because I do not have enrollment data for the

academic year 19992000. The estimation results reported in Table 5 are still insignificant when I divide

the incremental property value in year

t1

by the enrollment in the current year, or when I log this ratio.

25

New TIF districts are in the current year but not in the immediately preceding year, while expired TIF

districts exist in the immediately preceding year but not in the current year.

19

districts relative level of wealth or income (W).

26

This variable, W, is coded 0, 1, and 2 for

districts in which the median housing value in Census 2010 was below the 33rd percentile,

between the 33rd and 67th percentiles, and above the 67th percentile, respectively. If the

coefficient of

is significantly negative, a positive significant coefficient of the interaction term

then means that TIF has milder price effects on higher-wealth school districts. To test the

robustness of the results, I interact

with a variant of W, which is based on school districts

median household income in Census 2010.

27

<B>Potential Endogeneity

One might be concerned over potential endogeneity as a result of reverse causality

between education expenditures and TIF use. In a school district that expects education spending

to grow rapidly, its officials might be more resistant to TIF establishment than in school districts

with more stable spending. Put differently, school districts with low education spending are

prone to TIF adoption. If such a link between spending and TIF existed, estimated results would

be biased downward.

This concern for potential bias is not warranted for several reasons. First, although

previous studies recognize TIF to be potentially endogenous, none of them provides significant

evidence of endogeneity. Dye and Merriman (2000) reject endogenous TIF adoption; Man and

Rosentraub (1998) and Anderson (1990) find insignificant relationships between school district

related variables and TIF adoption; and Weber (2003) does not find evidence of endogenous TIF

in the estimations of school district revenues, state aid, and effective tax rates. Second, unlike

26

As shown and discussed in the results section,

does not show significant impacts on education

spending. Its interaction with W is not significant either and thus is not reported. The interaction between

W and T

P

is also insignificant and not reported.

27

W cannot be estimated separately. It is dropped in fixed effects models because it is constant for each

district.

20

their peers in other states, school districts in Iowa cannot choose to opt out of the TIF process.

28

Third, as argued in Weber, Hendrick, and Thompson (2008), the endogeneity is generally not an

issue for estimating the effects of TIF at the school district level because local governments

(mostly municipalities) that make TIF adoption decisions in Iowa are distinct from school

districts. The boundaries of school districts do not coincide with those of municipalities and

counties (the two jurisdictions with the authority to establish TIF districts). The designation of

TIF districts is, thus, unlikely to be correlated with school districts fiscal conditions. All in all,

potential downward bias is not a major cause for concern; one can, however, treat my estimates

as conservative.

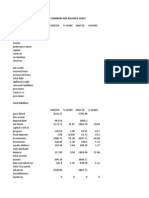

Table 2 provides summary statistics of all the variables used to estimate different variants

of equation (6), and their sources. The data included 347 school districts in Iowa between 2001

and 2011.

29

Of these, fifty districts did not have any TIF district during the sample period. Nearly

84 percent of the total observations had positive TIF values. Incremental taxable property values

per pupil within TIF districts represented by

showed marked growth and variation with the

standard deviation of $17,266.

30

Of the three major property types subject to TIF, commercial

properties provided school districts with the most incremental per pupil value, followed by

residential and industrial properties.

28

Overlapping jurisdictions may legally opt out of participation in the TIF process in eleven states

(Weber 2003).

29

There were 359 school districts as of the 20102011 academic year. However, given that district

consolidations have substantial expenditure implications (Duncombe and Yinger 2007), districts that were

reorganized or consolidated during the sample period were deleted from the dataset.

30

The summary statistics without the fifty non-TIF school districts are quite similar.

21

<A>Results

Table 3 presents the regression results on the general effects of TIF on education

expenditures (the first research question) with the specification of both

and

. (The results

are almost identical when they are estimated separately.) The coefficient of

is negative but

insignificant, showing ambiguous evidence of this variable on education spending. The other two

TIF measures, namely, tax price (

) and total incremental taxable property value per pupil (

),

show negative price effects on school expenditures, indicating lower demand for spending in

response to higher prices. A 1 percent increase in

and

is associated with a reduction of 0.12

and 0.0018 percent, respectively, in school district operating expenditures. I am unable to

directly quantify the impact of TIF with the coefficient of

. The price effect of TIF measured

by

on education expenditures is relatively small. Suppose that an average-spending district

that has the average

of $10,750 and enrollment of 1,344 increases its

by approximately one

standard deviation to slightly over $28,000. This 160 percent increase in

would induce a

reduction of only 0.29 percent (160 0.0018 percent) in this districts operating spending per

pupil ($31), thus, a reduction of $41,664 in total spending.

Many of the other variables are highly significant with expected signs. I find a quadratic

relationship between enrollment and education spending. While more students decrease

education expenditures per pupil, diseconomies of size start to set in at an enrollment of about

24,300. (In Iowa, only the enrollment of the Des Moines School District exceeds this threshold.)

A 1 percent increase in the share of low-income students is associated with an increase of nearly

0.02 percent in operating expenditures. Voters higher income also increases their demand for

education expenditures. The demand also becomes higher with increased income surtaxes and

state and federal aid. The effect of state aid is more than nine times larger than that of federal aid.

22

As with Nguyen-Hoang (2013), an increase in the shares of college graduates and homeowners

within a district is associated with higher school spending.

Table 4 reports the estimation results for the second research question regarding the

potential differential effects of different TIF types on education expenditures. This table shows

that incremental property values of residential and industrial properties in TIF districts are

negatively related with school district spending. An increase in the incremental values of

residential and industrial properties is associated with a reduction of 0.0012 percent,

respectively, in educational spending. This price effect of residential TIF on demand for

education spending can be explained by, as reviewed in Nguyen (2005), the negative, though

small, spillover effects of affordable housing on the values of nearby properties. (The primary

purpose of residential TIF in Iowa is to create affordable housing.) In keeping with the

theoretical framework, the negative price effect of industrial TIF on education expenditures may

be explained by negative spillover effects on nearby properties (Dye and Merriman 2003; Weber,

Bhatta, and Merriman 2007) and/or a positive growth trend of industrial TIF properties (Weber,

Bhatta, and Merriman 2003). The coefficient of commercial TIF is insignificant probably

because of mixed spillover effects of all commercial TIF districts within a school district on

nearby properties: some commercial TIF districts have positive spillovers (Merriman, Skidmore,

and Kashian 2011), others negative (Weber, Bhatta, and Merriman 2007).

Table 5 reports the results for the third and fourth research questions. In columns 1 and 2,

I find little empirical evidence for effects of expired TIF districts measured by either the ratio of

incremental taxable property value to total taxable value in year

t1

(

), or the number of expired

TIF districts within a school district (

). Although the signs of these two variables are positive

as expected (i.e., higher demand for education spending in response to lower prices), their

23

coefficients are not precisely estimated. This seemingly puzzling finding provides little support

for the argument that overlapping jurisdictions would benefit when TIF projects expire. This

finding can be plausibly explained by insufficient statistical power,

31

or by an unfavorable

attitude toward growth government spending among the large majority of voters. This attitude

may come from the voters fear of a ratchet effect in school district spending (i.e., once

increased, the spending will not be lowered).

Columns 3 and 4 of Table 5 provide evidence on the differential effects of TIF on the

education expenditures of school districts with different levels of wealth or income. A 1 percent

increase in

for the lowest wealth or income school districts (W = 0) is associated with a

reduction of 0.0034 or 0.0038 percent in education spending, respectively. This price effect for

the lowest income district group is approximately twice as large as the average effect reported in

Table 3. The positive significant interaction terms of logged

W in columns 3 and 4 suggest

that the negative price effect of TIF on educational expenditures becomes smaller for higher-

income school districts. While the spending of school districts in the middle group (between the

33rd and 67th wealth or income percentiles) is expected to decline by only 0.0015 or 0.0017

percent in response to a one-percent increase in

, changes in

have no significant effect on the

educational expenditures of school districts in the highest wealth or income group.

32

These

findings suggest that, all else being equal, cities in the lowest wealth or income group were more

likely to designate non-blighted areas as TIF districts even though property values would have

increased without TIF.

31

Compared to nearly 84 percent of the observations with positive TIF values, only 270 (or 7 percent of)

observations have at least one expired TIF district during the sample period.

32

Using column 3, the statistical test of a linear combination of (0.0034 + 2 0.0019) (with the lincom

Stata command) provides an insignificant result.

24

<A>Conclusion

Tax increment financing (TIF) has been a popular tool for economic (re)development in

many states. Of these, Iowa is a top user of TIF with more than 2,200 TIF districts. TIF has been

a hot-button policy issue in the state following recent reports on the (ab)use of TIF in Polk and

Johnson counties. Integral to the controversy is how TIF may affect overlapping taxing

jurisdictions, particularly school districts. On the one hand, proponents of TIF hold that voters in

a school district may demand greater education expenditures from lower tax prices associated

with a larger property tax base when one of these scenarios occur: cities in the district adopt TIF

for blighted areas that would have otherwise depreciated, TIF exerts positive spillover effects on

neighboring property, or TIF districts expire. On the other hand, opponents of TIF argue that

voters in a school district may face higher tax prices of education spending and thus demand less

of it when TIF district property values frozen during the TIF period would have increased

without TIF (and been available to the school district), or when TIF induces negative spillover

effects on property near TIF districts.

This is the first study to directly examine the relationship between TIF and education

expenditures. I find that greater use of TIF is associated with reduced education expenditures. I

also find little evidence to support the commonly held proposition that school spending increases

from TIF when TIF districts expire. This finding might reflect voters fear of the ratchet effect

(i.e., school spending, once increased, keeps going up). Finally, the negative price effect of TIF

on education spending is increasingly larger for school districts in lower wealth or income

groups compared to their peers in higher wealth or income groups. The effect of TIF on the

spending of school districts in the lowest income group is approximately twice as large as the

25

average effect. These school districts might have more non-blighted TIF districts that would not

have passed the but for test.

These findings have policy implications for Iowa and elsewhere. The negative, though

small, effect of TIF on education spending, coupled with no gain from the often-claimed long-

run benefits of TIF, justifies policy measures to protect school districts from TIF. For one, school

districts, as in Ohio, Georgia, Texas, and Pennsylvania, should be allowed to opt in, or out of,

TIF plans initiated by cities. In addition, the but-for test should be reinstated as a major

condition for TIF approval. Reinstating the test would particularly help the lowest-income school

districts most affected by TIF.

Finally, state education aid formulas could buffer the effects of TIF on education

expenditures. In Iowa, the aid is designed to make up the difference between the foundation level

and a school districts required contribution based only on its non-TIF tax base. Practically, the

state partially offsets the districts potential tax base losses from TIF. As noted earlier, the

negative price effect of TIF on education expenditures, which I find to be relatively small for

Iowa, is likely to be higher for states that employ a school districts total tax base (i.e., including

the TIF incremental value) to compute required local contributions in their state aid formulas.

Identifying and studying U.S. states that include TIF incremental value in the calculation of local

contributions would help reveal the full extent of TIF effects on education expenditures.

26

<A>References

Anderson, John E. 1990. Tax increment financing: Municipal adoption and growth. National Tax

Journal 43(2): 155163.

Andrews, Matthew, William D. Duncombe, and John Yinger. 2002. Revisiting economies of size

in American education: Are we any closer to a consensus? Economics of Education Review

21(3): 245262.

Bergstrom, Theodore C., and Robert P. Goodman. 1973. Private demands for public goods.

American Economic Review 63(3): 280296.

Bergstrom, Theodore C., Daniel L. Rubinfeld, and Perry Shapiro. 1982. Micro-based estimates

of demand functions for local school expenditures. Econometrica 50(5): 11831205.

Bossard, Jennifer A. 2011. The effect of tax increment financing on spillovers and school district

revenue. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Nebraska at Lincoln, Lincoln, NE.

Briffault, Richard. 2010. The most popular tool: Tax increment financing and the political

economy of local government. University of Chicago Law Review 77(1): 6595.

Byrne, Paul F. 2005. Strategic interaction and the adoption of tax increment financing. Regional

Science and Urban Economics 35(3): 279303.

Byrne, Paul F. 2006. Determinants of property value growth for tax increment financing districts.

Economic Development Quarterly 20(4): 317329.

Cory, Mark, and Patricia J. Martin. 2012. ABCs of Iowa urban renewal: A practical guide for

cities and counties. Des Moines, IA: Ahlers and Cooney, P.C.

Davidson, Jonathan M. 1978. Tax increment financing as a tool for community redevelopment.

University of Detroit Journal of Urban Law 56: 405444.

27

Downes, Thomas A., and Thomas Pogue. 1994. Adjusting school aid formulas for the higher

cost of educating disadvantaged students. National Tax Journal 47(1): 89110.

Duncombe, William D. 1996. Public expenditure research: What have we learned? Public

Budgeting and Finance 16(2): 2658.

Duncombe, William D., and John Yinger. 2007. Does school district consolidation cut costs?

Education Finance and Policy 2(4): 341375.

Duncombe, William D., and John Yinger. 2011. Making do: State constraints and local responses

in Californias education finance system. International Tax and Public Finance 18(3): 337368.

Dye, Richard F., and David F. Merriman. 2000. The effects of tax increment financing on

economic development. Journal of Urban Economics 47(2): 306328.

Dye, Richard F., and David F. Merriman. 2003. The effect of tax increment financing on land

use. In The property tax, land use, and land use regulation, edited by Dick Netzer, pp. 3761.

Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Dye, Richard F., and Jeffrey O. Sundberg. 1998. A model of tax increment financing adoption

incentives. Growth and Change 29(1): 90110.

Evans, William N., and Ioannis N. Kessides. 1993. Localized market power in the US airline

industry. Review of Economics and Statistics 75(1): 6675.

Fisher, Peter. 2011. Tax increment financing: A case study of Johnson County. Iowa City, IA:

Iowa Fiscal Partnership. Available www.iowafiscal.org/2011docs/111121-TIF-JC.pdf.

Fisher, Peter, and Michael Lipsman. 2012. Tax increment financing in Polk County. Iowa City,

IA: Iowa Fiscal Partnership. Available www.iowafiscal.org/2012docs/120315-TIF-polk.pdf.

Fox, William F. 1981. Reviewing economies of size in education. Journal of Education Finance

6(3): 273296.

28

Gill, Jeff, and Jason Gainous. 2002. Why does voting get so complicated? A review of theories

for analyzing democratic participation. Statistical Science 17(4): 383404.

Globerman, Steve, and Daniel Shapiro. 2008. The international mobility of highly educated

workers among OECD countries. Transnational Corporations 17(1): 235.

Hilber, Christian A. L., and Christopher J. Mayer. 2009. Why do households without children

support local public schools? Linking house price capitalization to school spending. Journal of

Urban Economics 65(1): 7490.

Lawrence, David B., and Susan C. Stephenson. 1995. The economics and politics of tax

increment financing. Growth and Change 26(1): 105137.

Lehnen, Robert G., and Carlyn E. Johnson. 2001. The impact of tax increment financing on

school districts: An Indiana case study. In Tax increment financing and economic development:

Uses, structures and impact, edited by Craig Johnson and Joyce Man, pp. 137154. Albany, NY:

State University of New York Press.

Man, Joyce Y. 1999. Fiscal pressure, tax competition and the adoption of tax increment

financing. Urban Studies 36(7): 11511167.

Man, Joyce Y., and Mark S. Rosentraub. 1998. Tax increment financing: Municipal adoption and

effects on property value growth. Public Finance Review 26(6): 523547.

Merriman, David F., Mark L. Skidmore, and Russ D. Kashian. 2011. Do tax increment finance

districts stimulate growth in real estate values? Real Estate Economics 39(2): 221250.

Mikesell, John. 2014. Fiscal Administration. 9th edition. Boston, MA: Wadsworth Publishing.

Nguyen, Mai Thi. 2005. Does affordable housing detrimentally affect property values? A review

of the literature. Journal of Planning Literature 20(1): 1526.

29

Nguyen-Hoang, Phuong. 2012. Cost function and its use for intergovernmental educational

transfers in Vietnam. Education Economics 20(1): 6991.

Nguyen-Hoang, Phuong. 2013. Tax limit repeal and school spending. National Tax Journal

66(1): 117148.

Nguyen-Hoang, Phuong, and John Yinger. 2011. The capitalization of school quality into house

values: A review. Journal of Housing Economics 20(1): 3048.

Nydle, Christopher M. 2009. Iowas agribusiness in a TIF. Drake Journal of Agricultural Law

14(3): 485450.

Pacewicz, Josh. 2013. Tax increment financing, economic development professionals and the

financialization of urban politics. Socio-Economic Review 11(3): 413440.

Perri, Brad. 2001. Financing the future: Interpreting the economic development area provision

of the Iowa TIF statute. Drake Law Review 50(1): 159179.

Robinson, Jeff. 2011. Tax increment financing. Presentation given to Iowa Senate Ways and

Means Committee, Des Moines.

Ross, Justin, and Phuong Nguyen-Hoang. 2013. School district income taxes: New revenue or a

property tax substitute? Public Budgeting and Finance 32(2): 1940.

Smith, Brent C. 2006. The impact of tax increment finance districts on localized real estate:

Evidence from Chicagos multifamily markets. Journal of Housing Economics 15(1): 2137.

Smith, Lauren Ashley. 2009. Alternatives to property tax increment finance programs: Sales,

income, and nonproperty tax increment financing. Urban Lawyer 41(4): 705724.

Swenson, David, and Liesl Eathington. 2002. Do tax increment finance districts in Iowa spur

growth or squander public resources? Unpublished paper, Iowa State University.

30

Swenson, David, and Liesl Eathington. 2006. Tax increment financing growth in Iowa.

Unpublished paper, Iowa State University.

Talanker, Alyssa, and Kate Davis. 2003. Straying from good intentions: How states are

weakening enterprise zone and tax increment financing programs. Washington, DC: Good Jobs

First.

Weber, Rachel. 2003. Equity and entrepreneurialism: The impact of tax increment financing on

school finance. Urban Affairs Review 38(5): 619644.

Weber, Rachel, Saurav Dev Bhatta, and David Merriman. 2003. Does tax increment financing

raise urban industrial property values? Urban Studies 40(10): 20012021.

Weber, Rachel, Saurav Dev Bhatta, and David Merriman. 2007. Spillovers from tax increment

financing districts: Implications for housing price appreciation. Regional Science and Urban

Economics 37(2): 259281.

Weber, Rachel, Rebecca Hendrick, and Jeremy Thompson. 2008. The effect of tax increment

financing on school district revenues: Regional variation and interjurisdictional competition.

State and Local Government Review 40(1): 2741.

31

Table 1 Numbers of School Districts Comprising TIF Districts

Year

2001

2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011

(1)

48 59 66 71 73 76 87 94 99 103 111

(2)

10 14 21 20 22 25 27 31 33 34 38

(3)

3 4 5 5 9 9 10 12 14 17 19

(4)

0 1 1 1 3 5 4 6 5 5 7

(5)

52 46 30 18 33 19 25 18 13 8 8

(6)

6 11 5 1 0 2 1 0 1 0 1

(7)

4 1 2 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0

(8)

87 97 86 88 70 62 74 77 79 60 76

(9)

20 28 26 22 15 17 21 23 20 11 22

(10)

11 12 14 7 7 5 6 5 5 4 6

(1), (2), (3), and (4) are the numbers of school districts that had 10, 20, 30, and 40 TIF districts,

respectively.

(5), (6), and (7) are the numbers of school districts that had 1, 3, and 5 expired TIF districts, respectively.

(8), (9), and (10) are the numbers of school districts that had 1, 3, and 5 new TIF districts, respectively.

Source: Authors calculations are based on data from the Iowa Department of Management.

32

Table 2 Summary Statistics for the Full Sample (20012011)

Variable Mean

Standard

Deviation

Min. Max. Source

Total operating expenditures per pupil 10,283 2,962 7,042 54,447 (1)

Tax price (T

P

) 0.42 0.21 0.03 1.30

(1), (2),

(4)

Total incremental property value per pupil (

) 10,750 17,266 0 218,647 (2)

Incremental per pupil value of residential property 3,674 7,766 0 149,040 (2)

Incremental per pupil value of commercial property 4,792 10,604 0 155,713 (2)

Incremental per pupil value of industrial property 1,908 4,567 0 49,636 (2)

Ratio of incremental taxable property value to total

taxable value in year

t1

0.0005 0.0044 0 0.0932 (2)

Enrollment 1,344 2,520 21 31,369 (1)

Percent of free and reduced-price lunch students 31.03 12.39 3.26 90.91 (1)

Percent of LEP students 1.72 4.83 0 58.66 (1)

Percent of African American students 1.44 2.68 0 30.22 (1)

Total state aid per pupil 4,341 1,023 93 16,548 (1)

Total federal aid per pupil 722 603 119 9,783 (3)

Median household income 52,523 10,162 30,314 103,353 (4)

Percent of college graduates 19.43 8.33 5.43 63.33 (4)

Percent of owner-occupied housing units 84.63 5.79 50.51 97.05 (4)

Notes: There are 3,817 observations (347 districts for eleven years from 2001 to 2011). Monetary measures are

adjusted for inflation (using government price indexes published by the Bureau of Economic Analysis) and in

2010 dollars. Sources are (1) Iowa Department of Education; (2) Iowa Department of Management; (3) Public

Elementary-Secondary Education Finance Data (www.census.gov/govs/school/); and (4) U.S. Census in 2000

and 2010 (the annual values for inter-census years and 2011 were interpolated and extrapolated by using the

linear growth rate between 2000 and 2010).

33

Table 3 General Effects of TIF on Education Expenditures

(dependent variable: logged total operating expenditures per pupil)

Variables Coefficients

Log of tax price (

) 0.12

(5.67)***

Log of incremental taxable property value

per pupil (

)

0.0018

(2.86)***

Number of new TIF districts within

school districts (

)

0.00033

(0.54)

Log of enrollment 1.01

(10.49)***

Squared log of enrollment 0.050

(7.40)***

Logged percent of free and reduced-price

lunch students

0.018

(2.12)**

Logged percent of LEP students

0.00036

(0.23)

Logged percent of African American

students

0.0017

(0.91)

Log of median household income

0.061

(1.74)*

Log of state aid per pupil 0.14

(4.28)***

Log of federal aid per pupil 0.015

(3.14)***

Log of income surtaxes per pupil 0.0028

(2.78)***

Percent of college graduates 0.0016

(1.74)*

Percent of owner-housing units 0.00077

(1.66)*

R

2

0.621

Notes: There are 3,817 observations between 2001 and 2011.

Regressions are estimated with district fixed effects and year

dummies. Hypothesis testing is done with the robust

heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation (HAC) Newey-West standard

errors. Numbers in parentheses are t-statistics.

* p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01

34

Table 4 Effects of Different Property TIF Types

Key Variables Coefficients

Log of tax price (T

P

) 0.12

(5.66)***

Log of incremental per pupil taxable property value of residential property 0.0012

(1.85)*

Log of incremental per pupil taxable property value of commercial property 0.00036

(0.60)

Log of incremental per pupil taxable property value of industrial property 0.0012

(2.07)**

Number of new TIF districts within school districts (

) 0.00034

(0.55)

Notes: All of the unreported variables and the other notes are the same as in Table 3.

* p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01

35

Table 5 TIF Effects of Expired TIF Districts and for Low-Income School Districts

Key Variables

Key Distinguishing Specification

Expired TIF

ratio (

and # of

expired TIF

districts (

)

School district

types based on

median housing

value

School district

types based on

median household

income

(1) (2) (3) (4)

Log of tax price (

) 0.12 0.12 0.12 0.12

(5.67)*** (6.20)*** (5.68)*** (5.73)***

Log of total incremental taxable

property value per pupil (

)

0.0018 0.0018 0.0034 0.0038

(2.86)*** (3.21)*** (3.46)*** (3.79)***

Number of new TIF districts

within a school district (

)

0.00034 0.00034 0.00035 0.00041

(0.54) (0.54) (0.55) (0.64)

Ratio of incremental taxable

property value to total taxable

value in year

t1

(

)

0.020 0.019 0.023 0.022

(0.11) (0.09) (0.11) (0.10)

Number of expired TIF districts

within a school district (

)

0.000022 0.000038 0.000058

(0.01) (0.02) (0.03)

Logged

W 0.0019 0.0021

(2.49)** (2.81)***

Notes: All of the unreported variables and the other notes are the same as in Table 3. W in column 3 is

coded 0, 1, and 2 for school districts whose median housing values in Census 2010 were below the 33rd

percentile, between the 33rd and 67th percentiles, and above the 67th percentile, respectively. W follows

the same coding procedure, except that the Census 2010 median household income is used.

* p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01

Вам также может понравиться

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Alabama-Slander-Of-title-etc-Amended Complaint - (Marcia Morgan, Richard E. Price - Argent Mortgage)Документ27 страницAlabama-Slander-Of-title-etc-Amended Complaint - (Marcia Morgan, Richard E. Price - Argent Mortgage)Kourtney TuckerОценок пока нет

- Tally Group Lists for Accounts, Expenses, Assets & LiabilitiesДокумент7 страницTally Group Lists for Accounts, Expenses, Assets & Liabilitieskrishna7852100% (2)

- 2019 07 Technical Guide CreditScoreДокумент52 страницы2019 07 Technical Guide CreditScoreAlexandru ToloacaОценок пока нет

- Kpds 2004 Kasım SonbaharДокумент20 страницKpds 2004 Kasım SonbaharDr. Hikmet ŞahinerОценок пока нет

- Condominium ActДокумент8 страницCondominium ActCMLОценок пока нет

- (1964) East Africa Law ReportsДокумент990 страниц(1964) East Africa Law ReportsRobert Walusimbi67% (9)

- Kroll Project Tenor Candu 02.04.15Документ6 страницKroll Project Tenor Candu 02.04.15Eugen BesliuОценок пока нет

- Architect Agreement Contract 2 PDFДокумент5 страницArchitect Agreement Contract 2 PDFS Lakhte Haider ZaidiОценок пока нет

- Chapter 6 - The Theory of CostДокумент11 страницChapter 6 - The Theory of Costjcguru2013Оценок пока нет

- Kyc Aml PDFДокумент25 страницKyc Aml PDFshruti tyagiОценок пока нет

- Land Lease Dispute Over First Priority to PurchaseДокумент2 страницыLand Lease Dispute Over First Priority to PurchaseSor Elle100% (1)

- Credit Transactions DefinedДокумент48 страницCredit Transactions DefinedDesiree Sogo-an PolicarpioОценок пока нет

- Analysis of Investment DecisionsДокумент88 страницAnalysis of Investment DecisionsManjulanbu Senthil KumarОценок пока нет

- 2012 Itr1 Pr21Документ5 страниц2012 Itr1 Pr21MRLogan123Оценок пока нет

- ValuationДокумент126 страницValuationAnonymous fjgmbzTОценок пока нет