Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Chapter 13 Pharynx

Загружено:

SMEY204Исходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Chapter 13 Pharynx

Загружено:

SMEY204Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13.

Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 1/40

Print | Close Window

Note: Large images and tables on this page may necessitate printing in landscape mode.

Skandalakis' Surgical Anatomy > Chapter 13. Pharynx >

HISTORY

The anatomic and surgical history of the pharynx is shown in Table 13-1.

Table 13-1. Anatomic and Surgical History of the Pharynx

Morgagni 1717 Described the pharyngeal sinus of Morgagni, a space in the nasopharynx between the upper border of the superior constrictor muscle and the

base of the skull

Rosenmller 1808 Described the lateral pharyngeal recess (fossa of Rosenmller)

Zukerkandl 1882 Described the pharyngeal tonsil

Mikulicz 1886 Reconstructed esophageal and pharyngeal stomas with inverted skin flaps

Beck 1905 Used reversed gastric tube

Jianu 1912

Gavriliu &

Georgescu

1951

Roux 1907 Used jejunum as pedicle graft

Herzen 1908

Vulliet 1911 Used transverse colon for reconstruction

Kelling 1911

Trotter 1913 Reconstructed the posterior and anterior hypopharyngeal wall with horizontal skin flaps

Kirschner 1920 Pioneered gastric transplantation, bringing the stomach to the neck

Wookey 1942 Developed a two-staged repair: doubled a long, full-thickness cervical pedicle flap and sutured it to the pharynx and esophagus, closing the

raw surface; repaired the fistula later by undercutting and suturing the skin margins

Hynes 1950 Performed pharyngoplasty by muscle transplantation, producing a sphincterlike mechanism

Goligher &

Robin

1954 Used left colon for reconstruction via presternal route

Asherson 1954 Performed partial excision of the posterior wall of the pharynx for carcinoma and used the proximal laryngotracheal tube for reconstruction

Seidenberg

et al.

1959 Developed microvascular technique using jejunum and anastomosing the mesenteric vessels to the superior thyroid artery and anterior facial

vein

Ong & Lee 1960 Performed pharyngogastric anastomosis after esophagopharyngectomy for correction of the laryngopharynx and cervical esophagus

Iskeceli 1962 Experimented with jejunal transplant to the pharynx in experimental animals

Bakamjian 1965 Used deltopectoral flap for pharyngoesophageal reconstruction

Ogura &

Dedo

1965 Used thoracoacromial flap to repair a pharyngostoma

Yamagishi et

al.

1970 Replaced esophagus up to the pharynx with a totally detached isoperistaltic gastric tube

Ariyan 1979 Used pectoralis major muscle flap for pharyngoesophageal reconstruction

McLear et al. 1991 Used jejunal free flap for reconstruction of hypopharyngeal stricture

Anthony et

al.

1994 Performed pharyngoesophageal reconstruction with radial forearm free flap

Wax et al. 1996 Reconstructed the oropharynx with lateral arm free flap

History table compiled by David A. McClusky III and John E. Skandalakis.

References

Missotten FEM. Historical review of pharyngo-oesophageal reconstruction after resection for carcinoma of pharynx and cervical oesophagus. Clin Otolaryngol

1983;8:345-362.

Pigott RW. The results of pharyngoplasty by muscle transplantation by Wilfred Hynes. Br J Plast Surg 1993;46:440-442.

Schmidt JE. Medical Discoveries: Who and When. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, 1959.

EMBRYOGENESIS

Normal Development

To understand the anatomy of the pharynx and its associated arteries and nerves and to avoid possible complications related to surgical treatment of

congenital lesions in this relatively inaccessible area, a thorough knowledge of the basic embryologic development of the pharynx is imperative. The pharynx

is a product of differentiation of the embryonic foregut. It occupies a major portion of the foregut in the first few weeks of embryonic development and

precedes the appearance of the more caudal regions. The cranial portion of the foregut transforms from a flat tube into a complicated collection of

structures between the fourth and sixth weeks of embryogenesis.

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 2/40

Structures derived from the pharynx can be divided into the lateral branchial apparatus and the unpaired ventral endodermal floor. [Note from the authors:

The term "branchial" is used in many chapters of this book. Nomina Anatomica, 6th edition, page E28, lists "branchial" as its second choice, and

"pharyngeal" as its first choice. Many current authors strongly prefer "pharyngeal" unless one is referring to lower vertebrates with gills, etc.]

The branchial apparatus contains paired endodermal pharyngeal pouches with ectodermal clefts. Mesodermal arches occur between the consecutive pairs.

The ventral structure gives rise to the tongue, thyroid, larynx, and trachea.

Externally, the branchial apparatus is marked by four ectodermal branchial clefts on each side of the pharynx of the embryo. On the inner surface, the

pharynx, which arises from the stomodeal plate, evaginates into five pouches. The first four of these correspond to the external branchial clefts.

Mesodermal arches (Fig. 13-1) are found between the corresponding cleft-pouch sets. Each arch contains a skeletal element, an artery, and the primordia

of nerves and muscles. The derivatives of the branchial arches are listed in Table 13-2. (Readers will notice that Table 13-2 indicates the existence of 6

arches. However, for all practical purposes, there are only 4, because the fifth disappears early, and the sixth unites with the fourth.)

Table 13-2. Summary of Adult Structures Derived from Pharyngeal Arches

Arch Derivatives

Pharyngeal

Arch

Muscles Skeletal Structures Ligaments Pouch Derivatives Groove

Derivatives

Nerve Supply

First

(mandibular)

Mastication

muscles

(Meckel's cartilage) Anterior ligament

of malleus

Tubotympanic recess (tympanic

membrane, tympanic cavity, mastoid

antrum, auditory tube)

External

auditory

canal

V (trigeminal)

Mylohyoid Malleus Sphenomandibular

ligament

Anterior belly of

digastric

Incus

Tensor tympani Ventral end of mandible

Tensor veli

palatini

Second

(hyoid)

Facial

expression

muscles

(Reichert's cartilage) Stylohyoid

ligament

Tonsillar fossa None VII (facial)

Stapedius Stapes

Stylohyoid Styloid process

Posterior belly of

digastric

Hyoid bone (lesser horn and

upper body)

Third Stylopharyngeus Hyoid bone (greater horn and

lower body)

None Inferior parathyroid None IX

(glossopharyngeal)

Thymus

Fourth and

sixth

combined

Cricothyroid Laryngeal cartilages (cricoid,

thyroid, arytenoid, corniculate,

cuneiform)

None Superior parathyroids None X (vagus)

Levator veli

palatini

Ultimobranchial bodies

Constrictors of

pharynx

Intrinsic muscles

of larynx

Source: Johnson KE, Slaby FJ, Bohn RC. Anatomy: Review for USMLE, Step 1, 2nd Ed. Alexandria, Va.: J & S Publishing, 1998, p. 83; with permission.

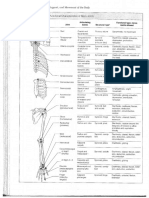

Fig. 13-1.

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 3/40

The branchial arch system. The arch system appears in the fourth and fifth gestational weeks as four prominent arches, each consisting of muscular and

cartilaginous components, a nerve, and an artery. (From Sadler TW. Langman's Medical Embryology, 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2000; with

permission.)

In the adult pharynx, the eustachian tube and the tonsillar fossa represent derivatives of the first and second branchial pouches respectively. The third

pouch is near the entry of the piriform recess, and the fourth is near the apex. Laryngeal ventricles may be related to the fifth and sixth pouches.

Congenital Anomalies of the Pharynx

Anomalies of the Lateral Branchial Apparatus

Epithelium-lined cysts, sinuses, and fistulas may occur as a result of malfunction in the normal differentiation process of the branchial apparatus.

Understanding the anomalies of the branchial apparatus helps the surgeon predict the location and course of these lesions and surrounding important normal

structures, and thus to avoid their injury at surgery.

First Cleft and Pouch Defects

The fistulas, sinuses, and cysts of the first branchial cleft are intimately related to the external auditory canal and the facial nerve; they are presented in

the chapter on the neck. First pouch defects are rare, but may present as nasopharyngeal cysts (Fig. 13-2). The opening of the sinuses can be near the

eustachian cushion.

Fig. 13-2.

Congenital cervicoaural fistula or cyst. This is a persistent remnant of the ventral portion of the first branchial cleft. The tract may or may not open into the external

auditory canal. (Modified from Skandalakis JE, Skandalakis PN, Skandalakis LJ. Surgical Anatomy and Technique: A Pocket Manual, 2nd Ed. New York: Springer,

2000; with permission.)

Second Cleft and Pouch Defects

Second cleft and pouch defects may involve the pharynx. Therefore these lesions and their courses are pertinent to understanding the pharynx.

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 4/40

COMPLETE FISTULAS

Almost all complete branchial fistulas are derived from the ventral portion of the second cleft and pouch. The external opening is in the lower third of the

neck, anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The fistula passes through the deep fascia to reach the carotid sheath. Above the hyoid, the tract turns

medially. It passes over and in front of the hypoglossal nerve and between the carotid bifurcation. It enters the pharynx on the anterior face of the

superior half of the posterior tonsillar pillar. Alternatively, the opening can be into the tonsil itself. Figure 13-3 depicts the course of the fistula of the

second branchial cleft and pouch.

Fig. 13-3.

Anomalies of the pharyngeal clefts and pouches. 2, fistulas of the second pharyngeal cleft and pouch. 3, fistula of the third pharyngeal cleft and pouch. 9,

glossopharyngeal nerve. 12, hypoglossal nerve. IC, internal carotid artery; EC, external carotid artery. (Modified from O'Rahilly R, Mller F. Human Embryology &

Teratology, 2nd ed. New York: Wiley-Liss, 1996; with permission.)

SINUSES OPENING INTO THE PHARYNX

Sinuses opening into the pharynx are rarely seen. They usually open into the upper half of the posterior tonsillar pillar or into the tonsil itself.

CYSTS

The cysts of the second pouch may present clinically as a bulging in the posterior tonsillar pillar. Most are encountered in the neck and may extend

between external and internal carotid arteries (Fig. 13-4).

Fig. 13-4.

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 5/40

Incomplete closure of the second branchial cleft or pouch may leave cysts. Type I, superficial, at the border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Type II, between

the muscle and the jugular vein. Type III, in the bifurcation of the carotid artery. Type IV, in the pharyngeal wall. Types I, II, and III are of second-cleft origin. Type

IV is from the second pouch. M, sternocleidomastoid muscle; V, jugular vein; A, carotid artery. (Modified from Skandalakis JE, Gray SW, Rowe JS Jr. Anatomical

Complications in General Surgery. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1983; with permission.)

Third Cleft and Pouch Defects

A complete fistula of the third cleft and pouch has never been reported. Such a fistula, theoretically, would pass below the eleventh cranial nerve, over the

superior laryngeal nerve and hypoglossal nerve, and posteromedial to the internal carotid artery. It would then open into the pharynx in the upper part of

the piriform recess (Fig. 13-3).

Internal sinus tracts derived from the third pouch have been reported. They originated from the apex of the left piriform recess in all cases.

Fourth Cleft and Pouch Defects

A complete fistula of the fourth cleft and pouch has not been reported. Theoretically, the route of this fistula (Fig. 13-5) would be from the apex of the

piriform recess, through the cricothyroid membrane (inferior to the cricothyroid muscle), descending into the tracheoesophageal groove and looping around

the artery of the fourth arch, passing cephalodorsal to the carotid, looping over the hypoglossal nerve, descending in the neck, passing through the strap

muscles and platysma, and exiting low in the neck, anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

Fig. 13-5.

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 6/40

The pathway of a fourth branchial pouch abnormality. (Modified from Donegan JO. Congenital neck masses. In: Cummings CW (ed). Otolaryngology - Head and

Neck Surgery, 2nd Ed. St Louis: Mosby Year Book, 1993; with permission.)

Surgical Considerations

A thorough understanding of the embryology of the branchial structures is essential for the head and neck surgeon. To aid in the complete surgical excision

of these structures and to avoid complications, it is important to understand their normal course.

First branchial cleft anomalies may come in close proximity to the facial nerve. Therefore, facial nerve identification and dissection is essential to avoid

facial paralysis.

Second branchial cleft anomalies, which are the most common, start in the mid-neck (anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle) and course up to the

tonsillar fossa. It is important to remove the entire tract up to the tonsil.

Third branchial cleft anomalies start lower in the neck and pass posteromedial to the internal carotid artery and travel caudally to end in the piriform recess.

Fourth branchial cleft anomalies are extremely rare and may present as recurrent thyroiditis. There are no clinical reports of tracts that follow the entire

theoretical course (see section above). Instead most start in the piriform apex, usually the left side, and end after only a short distance in the paratracheal

region.

Direct laryngoscopy is useful for finding the opening of the tract in the apex of the piriform recess (Fig. 13-6). Cannulation of the tract with a Fogarty

catheter is helpful for localization of the tract during neck dissection in the left paratracheal region. Identification of the recurrent laryngeal nerve is

important to avoid nerve injury, but may be difficult with previous infection.

Fig. 13-6.

Piriform apex fistula (marked by arrow). (From Jacobs IN, Gray R, Wyly B. Approach to branchial pouch anomalies that cause airway obstruction during infancy.

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1998;118(5):682-685; with permission.)

Ventral Defects

The embryogenesis and abnormalities of development of the thyroid, parathyroids, and thymus are beyond the scope of this chapter. Information about the

thyroid and parathyroids is included in the chapter on the neck; the thymus is considered in the chapter on the mediastinum. However, the anomalies of the

descent of the medial anlage, the thyroid, are important in the discussion of the pharynx as it pertains to the lingual thyroid because the entire thyroid may

locate in the oropharynx and cause an obstruction of the airway.

Lingual thyroid refers to the failure of the thyroid to descend to its normal location. This gland may be within the tongue, at the normal location of the

foramen cecum (Figs. 13-7A, B). It is usually the only thyroid tissue present in the patient. Inadvertent excision of the gland may result in permanent

hypothyroidism. Hormonal suppression is usually effective in decreasing the size of the lingual thyroid. Surgery may be selectively used in cases of airway

obstruction or swallowing difficulties refractory to hormonal suppression.

Fig. 13-7.

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 7/40

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 8/40

Ectopic thyroid gland. A, Sites along the path of descent of the thyroid from the foramen cecum (lingual thyroid) to the normal location. Hyperdescent to a site

beneath the sternum is also indicated. B, The method of exposure of a lingual thyroid gland and the scheme for control of hemorrhage. (Modified from Lemmon WT,

Paschal GW Jr. Lingual thyroid. Am J Surg 1941:52;82-85; with permission.)

SURGICAL CONSIDERATIONS

During the normal descent of the thyroid gland portions of the tract may remain (may fail to obliterate). These remnants are known as thyroglossal duct

cysts. The tract starts in the midline neck and extends to the foramen cecum. It is essential to excise the complete tract and incorporate the central body

of the hyoid bone. This is known as a Sistrunk procedure. Failure to excise the central body of the hyoid bone and follow the tract up the foramen cecum

increases the recurrence rate.

Regions of the Nasopharynx

The nasopharynx, oropharynx, and laryngopharynx together form the common aerodigestive tract known as the pharynx (Fig. 13-8). These three separate

regions are, from the surgeon's perspective, quite different and individually complex. Each region is unique with respect to the lesions that arise there, and

each has specific structural and functional considerations. The following pages discuss these three structures.

Fig. 13-8.

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 9/40

Alimentary and respiratory system in the head and neck. Medial aspect; sagittal section slightly to the right of the median plane. (Modified from Frick HF, Kummer B,

Putz RV (eds). Wolf-Heidegger's Atlas of Human Anatomy. Basel, Switzerland: Karger, 1990; with permission.)

Development of Nasopharynx

The nasopharynx is full of developmental and morphologic complexity. It contains:

Pouch of Luschka (pharyngeal bursa) (Fig. 13-9)

Fossa (pharyngeal recess) of Rosenmuller (Fig. 13-8)

Waldeyer's tonsillar ring (Fig. 13-10)

Eustachian (tubal) tonsil (Fig. 13-10)

Luschka's "gland" (the pharyngeal or third tonsil) (Fig. 13-10)

Eustachian cushion (torus tubarius) (Fig. 13-8)

Pharyngeal (extrasellar) hypophysis (Fig. 13-8)

Fig. 13-9.

Pharyngeal bursa and pharyngeal hypophysis as seen in a sagittal section of the head of an infant. (Modified from Hollinshead WH. Anatomy for Surgeons. New

York: Harper & Row, 1968; with permission.)

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 10/40

Fig. 13-10.

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 11/40

Waldeyer's tonsillar ring. A, sagittal view. B, axial view. (A, Modified from Hollinshead WH. Anatomy for Surgeons. New York: Harper & Row, 1968; B, Modified from

Skandalakis JE, Gray SW, Rowe JS Jr. Anatomical Complications in General Surgery. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1983; with permission.)

Developmental considerations (Fig. 13-11) include:

Rostral tip of the notochord

Hypophysial pouch (Rathke's pouch)

Craniopharyngeal canal

Presphenoid-basisphenoid synchondrosis

Spheno-occipital synchondrosis

Tubotympanic recess

Pneumatization of the superadjacent sphenoid sinus (age 7-8)

Development of the first two pharyngeal pouches on each side

Fig. 13-11.

A, Sagittal section through the cephalic part of a 6-week embryo showing Rathke's pouch as a dorsal outpocketing of the oral cavity and the infundibulum as a

thickening in the floor of the diencephalon. B and C, Sagittal sections through the developing hypophysis (a remnant of Rathke's pouch) in the 11th and 16th

weeks of development, respectively. Note formation of the pars tuberalis, encircling the stalk of the pars nervosa. (Modified from Sadler TW. Langman's Medical

Embryology, 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2000.)

The nasopharynx may also include the adenoids, Rathke's cleft cysts, chordomas, or craniopharyngioma.

Nomina Anatomica refers to the nasopharynx as the pars nasalis pharyngis, the nasal part of the pharynx. Although the nasopharynx is a part of the

pharynx, remember that it is a purely respiratory passage. Under normal circumstances, it is not a part of the digestive tract, as is the pharynx.

The pharynx arises as the expanded cephalic end of the embryonic foregut (Fig. 13-12). The nasal cavities develop separately from the foregut, arising

from the nasal pits which deepen into nasal sacs. Since the early 1900s, controversies have existed as to whether the nasopharynx should be considered

strictly a part of the nasal cavity, or if it should be regarded as part of the pharynx. From embryogenesis, it is known that some of the original cavity is

taken up into the lower part of the nasal cavities. A portion of the original pharyngeal cavity comes to lie above the level of the definitive palate. It is this

portion of the pharynx that contributes to at least a portion of the nasopharynx and unites with the deepest part of the nasal sacs.

Fig. 13-12.

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 12/40

A, Sagittal section through the nasal pit and lower rim of the medial nasal prominence of a 6-week embryo. The primitive nasal cavity is separated from the oral

cavity by the oronasal membrane. B, Similar section as in A, showing the oronasal membrane breaking down. C, A 7-week embryo with a primitive nasal cavity in

open connection with the oral cavity. D, Sagittal section through the face of a 9-week embryo, showing separation of the definitive nasal and oral cavities by the

primary and secondary palate. Definitive choanae are at the junction of the oral cavity and the pharynx. (Modified from Sadler TW. Langman's Medical Embryology,

8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2000; with permission.)

The caudal extent of the nasopharynx is above the plane of the soft palate (Fig. 13-8) at the level of the opening of the eustachian tube (derived from the

first pharyngeal pouch). Therefore, the nasopharynx is derived from the embryonic pharynx below the level of the eustachian tube orifice.

Rostral to the eustachian tube orifice, the nasopharynx develops from the deep extension of the nasal cavities. The preceding conclusions are based on the

histology and innervation of the two components of the nasopharynx. The nasal (anterior) nasopharynx possesses the highly vascular respiratory mucosa

that is rich in lymphatics and resembles the nasal cavity. Transition occurs at the level of the eustachian tube, where the posterior nasopharynx has

stratified squamous epithelium resembling that of the oropharynx.

Congenital Anomalies of the Nasopharynx

Anomalous nasopharyngeal development may be associated with abnormalities of the posterior nasal apertures, including choanal atresia, unilateral or

bilateral (Fig. 13-13), and malformation of the posterior aspect of the skull base. Gross abnormalities such as iniencephaly or anencephaly can also be

associated with nasopharyngeal wall malformations.

Fig. 13-13.

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 13/40

Axial CT (computed tomography) showing bilateral choanal atresia. White arrows indicate atretic plates. V, vomer. (Courtesy Ian N. Jacobs.)

SURGICAL ANATOMY

Surface Anatomy of the Nasopharynx

The nasopharynx extends from the choanae (posterior nasal apertures) (Fig. 13-14) and slopes upward and backward. Its shape follows the slope of medial

and lateral boundaries formed by the posterior edges of the vomer and the medial pterygoid plates, respectively (Figs. 13-14, 13-15).

Fig. 13-14.

Base of the skull. (Modified from Frick HF, Kummer B, Putz RV (eds). Wolf-Heidegger's Atlas of Human Anatomy, Basel, Switzerland: Karger, 1990; with permission.)

Fig. 13-15.

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 14/40

Skull, medial aspect; sagittal section slightly to the left of the median plane. (Modified from Frick HF, Kummer B, Putz RV (eds). Wolf-Heidegger's Atlas of Human

Anatomy. Basel, Switzerland: Karger, 1990; with permission.)

The anterior plane of the soft palate (Fig. 13-8) produces the lower extent of the nasopharynx. This plane intersects the anterior arch of the atlas in its

posterior extent. This is the narrowest part of the nasopharynx. It is called the isthmus, and it leads to the oropharynx below.

The nasopharynx is just inferior to the sphenoid bone (Fig. 13-15) and the posterior part of the sphenoid sinus. The hypophysial fossa (Fig. 13-15) and

pituitary gland are more cephalad to the sphenoid. The basilar portion of the occipital bone (Fig. 13-15) slopes downward, forming the anterior margin of

the foramen magnum (Figs. 13-14, 13-15), which is located posterosuperiorly to the nasopharynx.

Anterosuperiorly, the vomer articulates with the undersurface of the sphenoid bone (Fig. 13-15). Posterior to this articulation lies the pharyngeal sphenoidal

fossa. In this fossa lies the pharyngeal hypophysis (Fig. 13-8). Posterior to it, in the same tissue plane, one finds a collection of lymphoid tissue known as

the pharyngeal tonsil (Fig. 13-8).

Move inferiorly on the posterior wall of the nasopharynx to find the isthmus. Located below the basiocciput (Fig. 13-14) is the anterior arch of the atlas

(Fig. 13-8), and immediately behind it, the dens.

Numerous ligaments are located in this region. The anterior longitudinal ligament is the ligamentous structure most closely related to the posterior wall of

the nasopharynx.

The side walls of the nasopharynx are also extremely important. The most prominent structure is the opening of the auditory (eustachian) tube (Fig. 13-

14). This is located just behind the inferior nasal turbinate (concha) (Fig. 13-15). The overhang above and behind the orifice is known as the torus tubarius

(Figs. 13-8, 13-16). This is formed by the bulge of the fibrocartilage of the auditory tube itself. Gerlach's tonsil (eustatchian or tubal tonsil) (Figs. 13-8, 13-

10) is a collection of lymphoid tissue located in the mucous membrane over the pharyngeal orifice of the eustachian tube. The fossa of Rosenmuller

(pharyngeal recess) (Fig. 13-8, Fig. 13-17) is located behind the tubal orifice. This is a fairly deep and laterally directed structure. The superior pharyngeal

constrictor (Fig. 13-18) lies in the side wall of the nasopharynx. Dense pharyngobasilar fascia, which is attached to the skull base above and to the

pterygoid plate laterally (Fig. 13-14), is located on the inner aspect of the superior constrictor. The gap in the fascia allows the eustachian tube to pass.

On the outer aspect of the superior constrictor muscle is the weaker buccopharyngeal fascia. It provides a flimsy covering for the wall of the nasopharynx.

Fig. 13-16.

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 15/40

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 16/40

Pharyngeal cavity, dorsal aspect. The wall of the pharynx has been cut along the mid-dorsal line and opened. (Modified from Frick HF, Kummer B, Putz RV (eds).

Wolf-Heidegger's Atlas of Human Anatomy. Basel, Switzerland: Karger, 1990; with permission.)

Fig. 13-17.

Pharyngeal cavity, dorsal aspect. The wall of the pharynx has been cut along the middorsal line and opened; the mucous membrane and the superior pharyngeal

constrictor muscle have been partially removed in order to expose the different muscles. (Modified from Frick HF, Kummer B, Putz RV (eds). Wolf-Heidegger's Atlas

of Human Anatomy. Basel, Switzerland: Karger, 1990; with permission.)

Fig. 13-18.

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 17/40

Muscular wall of the pharynx, dorsal aspect. (Modified from Frick HF, Kummer B, Putz RV (eds). Wolf-Heidegger's Atlas of Human Anatomy. Basel, Switzerland:

Karger, 1990; with permission.)

An important feature of the nasopharynx is the development of the first two pharyngeal pouches on either side of this cavity (Fig. 13-8, Fig. 13-9). This

relationship is important with respect to the development of Waldeyer's ring (Figs. 13-10A & 13-10B). This is an incomplete ring of lymphoid tissue

composed of the pharyngeal tonsil, eustachian tonsil, palatine tonsil, and lingual tonsil.

Lying close to the nasopharynx are two noteworthy embryologic structures: the rostral segment of the notochord and the craniopharyngeal canal (Fig. 13-

11). Tumors (chordoma and craniopharyngioma, respectively) may arise from these. Both may involve the nasopharynx.

Examination of the Nasopharynx

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 18/40

Examination of the Nasopharynx

When the nasopharynx is examined indirectly with a mirror or endoscopically, several significant features become apparent. The perichoana with the

posterior tips of the inferior, middle, and superior turbinates (conchae) (Figs. 13-8, 13-16) are readily seen. The posterior vomer sharply divides the

posterior choanae (Fig. 13-14). Enlargement of the turbinates (conchae), adenoids, or polyps, or a mucopurulent nasal discharge can be readily apparent in

this region. Adenoids usually begin to atrophy after thirteen years of age, and if present in an adult, neoplasia should be considered. Enlarged adenoids in

an adult may also raise suspicion for lymphoepithelial hyperplasia associated with an HIV infection. On the exam, juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas can

be seen as smooth pulsatile masses, which should never be biopsied because the vascularity of the tumor and the brisk bleeding that accompanies biopsy

creates the potential for severe hemorrhage.

Several important landmarks in addition to the torus tubarius (Fig. 13-16) can be seen when the nasopharynx is examined during nasopharyngoscopy. The

salpingopharyngeus muscle (Fig. 13-17) is seen to sweep posteriorly and inferiorly from the posterior part of the torus, forming a raised mucosal fold (Fig.

13-16). The pharyngeal recess previously mentioned is actually formed between the pharyngeal wall and the elevation produced by this fold. Gerlach's tonsil

underlies this fold. Slight elevation of mucosa in the center of the eustachian tube opening is produced by the underlying levator veli palatini muscle (Figs.

13-8, 13-17). Looking at the roof of the nasopharynx, depression in the midline is frequently seen. This concavity is known as the pharyngeal bursa (Fig.

13-8). The mucosa of this bursa is infiltrated by lymphatic nodules at its periphery, which if sufficiently hyperplastic, forms the adenoids. A persistent

remnant of the embryonic notochord in this area may occasionally be seen as a cystic midline nasopharyngeal mass. This is known as the Thornwaldt's cyst

and is usually seen later in life.

Residual epithelial elements of Rathke's pouch (Fig. 13-11), an evagination of the stomodeal roof that contributes to the anterior pituitary gland, can give

rise to a craniopharyngioma. These usually occur just superior to the pharyngeal bursa in the midline of the nasopharynx, and may also be present as

nasopharyngeal masses (Fig. 13-9).

Surgical Considerations

Nasopharyngoscopy, whether with direct flexible or rigid telescopes, allows visualization of the structures and landmarks described above. An indirect mirror

exam will also allow excellent visualization of the nasopharynx. However, the latter is limited by the experience of the examiner, the inverted nature of the

mirror image, and the cooperation of the patient if the exam is done outside the operating room.

The best way to examine the nasopharynx in detail is under general anesthesia with the patient in a supine position. The soft palate (Figs. 13-8, 13-16)

can be retracted by passing catheters through the nares into the oral cavity and out through the mouth. The ends of such catheters are clamped and a

mirror is used by the examiner located at the head of the patient to survey the nasopharynx, denote the structural features, and to perform a variety of

procedures. These procedures include adenoidectomy, biopsies of any areas suspicious for malignancy, removal or marsupialization of polyps and cysts,

cannulation of eustachian tubes, and surgery for nasopharyngeal stenosis (Fig. 13-19). A thorough examination of the three dimensional structure of the

nasopharynx under general anesthesia is essential in planning a surgical repair, such as with laterally-based pharyngeal flaps.

Fig. 13-19.

Severe nasopharyngeal stenosis; complete cicatrix of the nasopharynx. (Modified from McLaughlin KE, Jacobs IN, Todd NW, Gussack GS, Carlson G. Management of

nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal stenosis in children. Laryngoscope. 107:1322-1331, 1997; with permission.)

Nasopharyngeal examination under general anesthesia is also useful for choanal atresia surgery, although in these cases the catheters cannot always be

passed through the nose; different maneuvers to retract the palate may be necessary.

With respect to malignancies confined to the nasopharynx, it is imperative that a complete nasopharyngeal exam is performed and that the examiner is fully

aware of the normal anatomy and variations of the nasopharynx. In the case of patients who present with neck masses suggestive of malignancy, a

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 19/40

aware of the normal anatomy and variations of the nasopharynx. In the case of patients who present with neck masses suggestive of malignancy, a

nasopharyngeal exam must always be a part of their head and neck examination. It is also extremely important to examine the nasopharynx of the patients

who present with nasal obstruction, epistaxis, or serous otitis media. All of these may result from benign or malignant processes in this region. For example,

angiofibromas may cause intermittent epistaxis as well as nasal obstruction. A process near the eustachian tube orifice, such as nasopharyngeal carcinoma

or lymphoma, may have unilateral serous otitis media as its only symptom.

Important Anatomic Relationships

Nasopharyngeal walls are composed of four layers from inside to outside:

Mucosa

Submucosa or fibrous layer (pharyngobasilar fascia)

Muscular layer

Buccopharyngeal fascia covering the constrictor muscles

The mucous membrane containing ciliated respiratory and nonciliated columnar epithelium is the inner lining. Submucosal connective tissue made of

pharyngobasilar fascia is well defined in its attachment to the skull base (Fig. 13-18). External to the superior constrictor muscle is the buccopharyngeal

fascia (Fig. 13-16). Attachment of the nasopharynx to the skull base is extremely important. Significant relationships to the middle cranial fossa, to the

dehiscence between the petrous temporal bone and foramen lacerum (Fig. 13-14), and to the carotid canal are apparent (Fig. 13-14).

The nasopharynx is attached in the midline to the pharyngeal tubercle on the basal surface on the body of the occipital bone (Fig. 13-18). This attachment

extends bilaterally to the petrous temporal bone (Fig. 13-15), and turning forward, continues to the posterior margin of the medial pterygoid plate (Fig. 13-

14) and the pterygoid hamulus (Fig. 13-15). The fossa of Rosenmuller (Figs. 13-8, 13-17) lies in the roof of the nasopharynx. Because the internal carotid

artery (Fig. 13-20) passes through the foramen lacerum it is close to the nasopharyngeal wall. Expanding masses in the nasopharynx, therefore, can involve

and jeopardize the carotid.

Fig. 13-20.

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 20/40

Arteries of the skull, medial aspect. Median section. (Modified from Frick HF, Kummer B, Putz RV (eds). Wolf-Heidegger's Atlas of Human Anatomy. Basel,

Switzerland: Karger, 1990; with permission.)

The roof of the nasopharynx is the floor of the middle cranial fossa. The sphenoidal sinus (Fig. 13-21), sella turcica, and cavernous sinus in the parasellar

region are in close proximity to each other. The middle cranial fossa can be invaded by the tumors of the nasopharynx. Natural routes are via the foramen

ovale. Direct extension into the middle cranial fossa can also occur from the roof of the nasopharynx via the foramen lacerum (Fig. 13-14). Growth patterns

of nasopharyngeal tumors are not well defined. However, some theories have been proposed based on surgical anatomy of the specimens. Tumors can

spread into the orbit, pterygopalatine fossa, infratemporal fossa, and sphenoid sinus or penetrate intracranially. They can thus cause blindness or

destruction of the pituitary, as well as extension into the anterior cranial fossa.

Fig. 13-21.

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 21/40

Coronal, slightly oblique section through the middle cranial fossa, showing the cavernous and cerebral portions of the internal carotid artery and cavernous sinus.

Nasopharyngeal lesions may also involve the retropharyngeal or parapharyngeal spaces (Figs. 13-22, 13-23). This can occur since the buccopharyngeal

fascia covering the external surface of the nasopharynx is connected to the prevertebral fascia of the deep layer of the deep cervical fascia. This creates

a space between the two fascial layers, known as the retropharyngeal space. Another space located laterally occurs between the buccopharyngeal fascia

and the fascia of the pterygoid muscles. Near the nasopharynx, that space is called the parapharyngeal space. Tumors or infections can invade this space

readily.

Fig. 13-22.

Fascial spaces of the head and neck region. (Modified from Hollinshead WH. Anatomy for Surgeons. New York: Harper & Row, 1968; with permission.)

Fig. 13-23.

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 22/40

Sagittal view of fascial spaces of head and neck region. (Based on Hollinshead WH. Anatomy for Surgeons, Vol. 1, 2nd ed. New York: Harper & Row, 1968.)

Important structures that pass between the skull base and the superior constrictor muscles can usually be seen on anatomic specimens. Removing the

mucosa from the medial aspect will reveal the tensor veli palatini (Fig. 13-17) and levator veli palatini muscles, ascending palatine artery, and ascending

pharyngeal artery (Fig. 13-24). The salpingopharyngeus muscle (Fig. 13-17) can also be revealed.

Fig. 13-24.

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 23/40

Blood vessels and nerves on the dorsolateral wall of the pharynx, dorsal aspect. The right side especially emphasizes the blood vessels, the left side the nerves.

(Modified from Frick HF, Kummer B, Putz RV (eds). Wolf-Heidegger's Atlas of Human Anatomy. Basel, Switzerland: Karger, 1990; with permission.)

The main muscles of the nasopharynx are the tensor and levator veli palatini muscles (Fig. 13-17). These are located in the space between the skull base

and the superior constrictor muscle, which will be described under "Myofascial Framework." This space is sealed by the pharyngobasilar fascia (Fig. 13-18).

These muscles originate from the pterygoid fossa between the lateral and medial pterygoid plates (Fig. 13-14). They insert into the soft palate (Figs. 13-8,

13-16).

The head and neck surgeon must be familiar with several important considerations. The anterior soft palate is tensed by the action of the tensor veli

palatini muscle. This muscle is thought to have an important role in eustachian tube opening and thereby in pressure equalization between the middle ear

and the nasopharynx. Other authors implicate the levator veli palatini in this function.

The levator veli palatini crosses the superior border of the superior constrictor muscle and enters the nasopharyngeal mucosa and the lateral border of the

soft palate. Contraction of the levator veli palatini muscles elevates the soft palate and seals the oral cavity from the oropharynx. This principle is

important when treating patients with velopharyngeal insufficiency and its associated deglutition and speech problems.

Two arteries travel the space below the skull base. These are the ascending pharyngeal, arising from the bifurcation of the internal and external carotid

arteries, and the ascending palatine artery, a branch of the facial artery (Fig. 13-24). These vessels are the main contributors of blood supply to the

nasopharynx.

Although the anatomy of the skull base is beyond the scope of this chapter, familiarity with the location of two structures is important. The foramen

spinosum (Fig. 13-14) is a conduit for the middle meningeal artery (Fig. 13-20). The foramen ovale (Fig. 13-14) provides passage to the mandibular branch

of the trigeminal nerve (Fig. 13-21). These foramina may allow spread of malignancies with origins in the intracranial nasopharynx.

The nasopharynx is relatively insensitive, with the main sensory innervation provided by the branches of maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve (Fig. 13-

25): the greater and lesser palatine nerves. Cranial nerve IX, the glossopharyngeal nerve (Fig. 13-24), supplies sensory innervation to the mucosal wall as

far superiorly as the eustachian tube. Procedures on the nasopharynx, such as mucosal biopsies and adenoidectomies, however, are relatively painless and

postoperative requirements for analgesics are minimal.

Fig. 13-25.

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 24/40

Arteries and nerves in the lateral wall of the nasal cavity, palate, and infratemporal fossa, medial aspect. (Modified from Frick HF, Kummer B, Putz RV (eds). Wolf-

Heidegger's Atlas of Human Anatomy. Basel, Switzerland: Karger, 1990; with permission.)

Surgical Considerations

A very important point in a nasopharyngeal surgical procedure, such as adenoidectomy, is the proximity of the atlanto-axial joint (Fig. 13-8). Muscle spasm

or infection after surgery may result in atlanto-axial dislocation, known as Grisel's syndrome. Patients with trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) are at higher risk for

this unusual complication.

A variety of benign and malignant neoplasms may occur in the nasopharynx (Tables 13-3 and 13-4). Congenital lesions such as chordomas and

craniopharyngiomas may also be present. Malignancies of the salivary glands as well as melanomas and esthesioneuroblastomas (olfactory neuroblastomas)

may also be found in the nasopharynx.

Table 13-3. Benign Non-Epithelial Tumors, Involving the Nasal Cavity, Paranasal Sinuses, and Nasopharynx 156 Cases

Vascular tumors 81

Capillary hemangioma 30

Cavernous hemangioma 5

Venous hemangioma 3

Benign hemangioendothelioma 3

Angiomatosis 1

Glomus tumor 1

Angiofibroma 38

Osseous and fibro-osseous tumors 52

Osteoma 31

Fibrous dysplasia 9

Ossifying fibroma 7

Osteoblastoma 1

Giant cell tumor 4

Chondroma 7

Myxoma 7

Fibroma 5

Leiomyoma 2

Lipoma 1

Rhabdomyoma 1

Source: Fu YS, Perzin KH. Non-epithelial tumors of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses, and nasopharynx: a clinicopathologic study. I. General features and vascular

tumors. Cancer 33:1275-1288, 1974; with permission.

Table 13-4. Malignant Tumors of Nasopharynx from the Mayo Tissue Registry, 1972 to 1981

Tumor Type Number (%)

Squamous cell carcinoma* 120 (71)

Lymphoma 31 (18)

Miscellaneous 18 (11)

Adenocarcinoma 6

Plasma cell myeloma 3

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 25/40

Cylindroma 2

Rhabdomyosarcoma 2

Melanoma 2

Fibrosarcoma 1

Carcinosarcoma 1

Unclassified, spindling malignant 1

neoplasm

Total 169 (100)

*Combined World Health Organization types 1, 2, and 3.

Source: Neel HB III. Benign and malignant neoplasms of the nasopharynx. In: Cummings CW. OtolaryngologyHead and Neck Surgery (2nd ed). St. Louis: Mosby,

1993; with permission.

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma deserves special attention. The complaints of patients with nasopharyngeal carcinomas are related to the location of the primary

tumor and the degree of spread. This is also reflected in the staging of these lesions (Table 13-5). Hearing loss and neck masses are the most common

complaints. A tumor in the lateral nasopharynx near or directly involving the mucosa of the eustachian tube orifice leads to tubal compromise. Symptoms of

ear blockage, serous otitis media and hearing loss can be present. The nasopharynx is richly supplied by lymphatics. These communicate across the midline

and allow for the bilateral metastases to the lymph nodes of the neck by way of the retropharyngeal lymph nodes. High cervical nodes in the posterior

triangle (Fig. 13-26) are often affected first.

Table 13-5. Current Pharynx Cancer Staging

Pharynx (including base of tongue, soft palate, and uvula)

Primary tumor (T)

Tx Primary tumor cannot be assessed

T

0

No evidence of primary tumor

T

is

Carcinoma in situ

Oropharynx

T

1

Tumor 2 cm or less in greatest dimension

T

2

Tumor more than 2 cm but not more than 4 cm in greatest dimension

T

3

Tumor more than 4 cm in greatest dimension

T

4

Tumor invades adjacent structures, e.g., through cortical bone, soft tissue of neck, deep (extrinsic) muscle of tongue

Nasopharynx

T

1

Tumor limited to one subsite of nasopharynx

T

2

Tumor invades more than one subsite of nasopharynx

T

3

Tumor invades nasal cavity or oropharynx

T

4

Tumor invades skull or cranial nerve(s)

Hypopharynx

T

1

Tumor limited to one subsite of hypopharynx

T

2

Tumor invades more than one subsite of hypopharynx or an adjacent site, without fixation of hemilarynx

T

3

Tumor invades more than one subsite of hypopharynx or an adjacent site, with fixation of hemilarynx

T

4

Tumor invades adjacent structures., e.g., cartilage or soft tissues of neck

Source: Beahrs OH, Henson DE, Hutter RVP, Kennedy BJ. AJCC Manual for Staging of Cancer, 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1992; with permission of the

American Joint Committee on Cancer, Chicago, Illinois.

Fig. 13-26.

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 26/40

Superficial cervical and facial lymph nodes. (Modified from Genden EM, Thawley SE, O'Leary MJ. Malignant neoplasms of the oropharynx. In: Cummings CW,

Fredrickson JM, Harker LA, Krause CJ, Richardson MA, Schuller DE (eds). Otolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery, 3rd ed. St Louis: Mosby, 1998; with permission.)

Large primary tumors of the nasopharynx obstruct the choanae and nasal airway and can lead to nasal obstruction as well as to epistaxis. Superior

extension via the foramen lacerum into the cranium can lead to cranial nerve involvement. Most commonly, cranial nerve VI is the first to be involved with

resulting lateral rectus muscle palsy and diplopia. Ophthalmoplegia can occur from involvement of cranial nerves III and IV. High neck and facial pain

signifies involvement of cranial nerve V. As the tumor enlarges, cranial nerves VII, IX, X, and XI can be affected (Figs. 13-24, 13-25, 13-27).

Fig. 13-27.

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 27/40

A, Sagittal view showing parapharyngeal and retropharyngeal spaces and associated anatomic structures. B, Axial view of the parotid gland and the carotid artery,

and of the peritonsillar, retropharyngeal (space 3), danger (space 4), prevertebral (space 5), and parapharyngeal (lateral pharyngeal) spaces. BPF,

buccopharyngeal fascia; RPS, Retropharyngeal space; DS, Danger space; PVS, Prevertebral space; CN, cranial nerve.

The nasopharynx is an extremely complex three dimensional structure with close proximity to the brain, carotid artery, sphenoid sinus, and a variety of

other important structures and nerves (Fig. 13-21). It is involved in breathing, deglutition, and phonation. Hence, it is imperative that a surgeon operating

in this area be thoroughly familiar with the embryologic, anatomic, and physiologic aspects of the nasopharyx. This avoids potentially disastrous

complications.

Oropharynx-Laryngopharynx

The next two regions of the pharynx to be discussed are the oropharynx, continuous with the oral cavity above, and the laryngopharynx, continuous with

the esophagus below. The pharynx is a myofascial framework enclosing the pharyngeal lumen and its contents. The external surfaces of the pharynx make

up the portions of the borders of important deep neck spaces which are involved in various disease processes. Understanding the anatomy and relationships

of the pharynx is important in making sound judgments regarding surgical approaches to the pharynx and adjacent structures.

The following section discusses the anatomy of the pharynx, first describing the myofascial framework. Then we describe the important structures

traversing this framework en route to the pharynx, the structures constituting the oropharynx and laryngopharynx, and the important structures bordering

the pharynx.

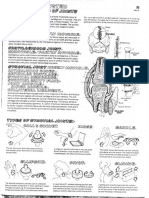

Myofascial Framework

The pharyngeal wall is composed of stratified squamous epithelium, which covers the internal surface of the myofascial layer. This layer extends from the

skull base superiorly to the level of the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage inferiorly (Fig. 13-8). This myofascial layer is composed of three paired U-

shaped muscles that open anteriorly: the superior, middle, and inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscles (Figs. 13-18, 13-28). These muscles form a

telescoping structure with the lower muscles overlapping the upper muscles at the inferior border. All three sets of muscles insert posteriorly on a midline

posterior pharyngeal raphe, suspending superiorly from the pharyngeal tubercle of the basiocciput.

Fig. 13-28.

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 28/40

Muscles of the tongue, pharynx, and larynx, lateral aspect. (Modified from Frick HF, Kummer B, Putz RV (eds). Wolf-Heidegger's Atlas of Human Anatomy. Basel,

Switzerland: Karger, 1990; with permission.)

These paired pharyngeal constrictor muscles are covered internally and externally by fascial layers. Internally, the constrictor muscles are covered by the

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 29/40

These paired pharyngeal constrictor muscles are covered internally and externally by fascial layers. Internally, the constrictor muscles are covered by the

pharyngobasilar fascia, which is thick superiorly and thin inferiorly and covers the muscles the length of the pharynx. Superiorly, the pharyngobasilar fascia

attaches to the pharyngeal tubercle of the occiput (Fig. 13-28), extends along the petrous portion of the temporal bone, and attaches anteriorly to the

medial pterygoid plate (Fig. 13-14) and the pterygomandibular raphe. The upper, thick portion of this fascia suspends the superior constrictor muscle from

the skull base. The external surface of the muscle is covered by the buccopharyngeal fascia. This fascia covers the pharynx at the level of the superior

constrictor muscle and fuses below this level with the middle layer of deep cervical fascia. This third fascia forms the remainder of the external fascial

covering of the pharynx.

The superior pharyngeal constrictor muscles originate from the medial pterygoid plate and pterygomandibular raphe anteriorly. Their fibers extend posteriorly

in a horizontal and slightly superior and inferior direction to insert on the posterior midline pharyngeal raphe (Fig. 13-18). These muscles surround the

oropharynx.

The middle pharyngeal constrictor muscles originate anteriorly from the greater and lesser cornua of the hyoid bone (Fig. 13-28). Their fibers extend

posteriorly in three separate groups (superior, middle, and inferior) to attach on the posterior midline raphe (Fig. 13-18). The middle constrictors are at the

level bridging the junction between the lower oropharynx and upper laryngopharynx.

The inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscles are the thickest of the pharyngeal constrictors and the best developed. These arise anteriorly from the oblique

line of the thyroid and cricoid cartilages (Fig. 13-28). They then extend posteriorly in a horizontal, superior, and inferior direction to insert on the posterior

midline raphe. The cephalic portion of the inferior constrictor muscle is termed the cricopharyngeus muscle. The cricopharyngeus muscle forms the upper

esophageal sphincter. It extends from the cricoid cartilage in a horizontal direction and interdigitates with the transverse esophageal muscle layer.

Intervals between the overlapping layers of pharyngeal constrictor muscles are traversed by structures entering the pharynx. The interval between the

superior and middle constrictor muscles is traversed by the stylopharyngeus muscle (Fig. 13-18). This muscle originates from the styloid process and

extends inferiorly and anteriorly in an oblique fashion to attach to the medial aspect of the middle constrictor muscle. The glossopharyngeal nerve supplies

sensory innervation to the base of the tongue and pharynx and also traverses this interspace (Fig. 13-24). The glossopharyngeal nerve and the lingual

artery course together, running deep to the hyoglossus muscle (Fig. 13-28). The stylohyoid ligament, which attaches to the lesser cornu of the hyoid bone,

also traverses this interval between the superior and middle pharyngeal constrictor muscles. Lying at the inferior pole of the palatine tonsil, the interval

provides a pathway of extension for an infectious process from the peritonsillar area to the parapharyngeal space, lateral to the superior constrictor muscle.

The interval between the middle and inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscles is occupied by the thyrohyoid membrane (Fig. 13-28). The structures traversing

this membrane include the internal laryngeal nerve and superior laryngeal artery and vein (Fig. 13-24). The internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve

enters the thyrohyoid membrane and supplies sensory innervation to the supraglottic larynx and the piriform recess mucosa. The external branch of the

superior laryngeal nerve continues inferiorly, lateral to the constrictor muscles, and accompanies the superior thyroid vessels (Fig. 13-24) to innervate the

cricothyroid muscle (Fig. 13-28). The internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve penetrates the thyrohyoid membrane approximately 1 cm inferior and

medial to the greater cornu of the hyoid bone. Infiltration of local anesthetic in this area will create a superior laryngeal nerve block and anesthetize the

laryngopharynx and supraglottic larynx. This is also the area of the thyrohyoid membrane where an external laryngocele will extend from the endolaryngeal

cavity to the extralaryngeal space.

The interval between the inferior constrictor muscles and the transverse fibers of the esophageal muscle transmits a neurovascular bundle. This bundle

includes the recurrent laryngeal nerve (Fig. 13-29). This nerve supplies sensory innervation to the glottis and subglottis and motor innervation to the

intrinsic laryngeal muscles except the cricothyroid muscle. Also in this bundle are the inferior laryngeal artery and vein, branches of the thyrocervical trunk

of the subclavian vessels.

Fig. 13-29.

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 30/40

Pharyngoesophageal segment showing potential areas of herniation. (Based on Hollinshead WH. Anatomy for Surgeons, Vol. 1, 2nd ed. New York: Harper & Row,

1968.)

The innervation of the pharyngeal muscles is from the pharyngeal plexus (Fig. 13-24). This is composed of the pharyngeal branches of the glossopharyngeal

and vagus nerves. The glossopharyngeal nerve supplies only the stylopharyngeus muscle. The vagal contribution supplies all the other muscles, including

the muscles of the soft palate (Fig. 13-30), with the exception of the tensor palatini muscle, which is supplied by the mandibular branch of the trigeminal

nerve (Fig. 13-25). The inferior constrictor muscle also receives innervation from the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve (Fig. 13-24). The

cricopharyngeus muscle may receive some innervation from the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Sensory innervation of the pharynx is supplied by the

glossopharyngeal nerve through the pharyngeal plexus. This supplies the mucosa of the oropharynx and laryngopharynx with the exception of the piriform

recess mucosa. The piriform recess mucosa receives its innervation from the internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve, which traverses the submucosa

in the anterior wall of the piriform recess (Fig. 13-16).

Fig. 13-30.

Muscles of the soft palate (cut away to show the levator veli palatini). (Modified from Hollinshead WH. Anatomy for Surgeons. New York: Harper & Row, 1968; with

permission.)

The vascular supply of the pharyngeal walls is from the ascending pharyngeal artery and the superior thyroid artery, branches of the external carotid artery

(Fig. 13-24). The inferior thyroid artery, a branch of the thyrocervical trunk, also provides arterial supply to the laryngopharynx. The venous drainage of the

pharynx is through the pharyngeal plexus on the posterior surface of the pharynx. This drains into the pterygoid plexus, the superior and inferior thyroid

veins, the facial vein, and directly into the internal jugular vein (Fig. 13-31).

Fig. 13-31.

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 31/40

Blood vessels and nerves of the neck, ventrolateral aspect. Parotid gland, sternocleidomastoid muscle, supra- and infrahyoid muscles have been partially removed.

(Modified from Frick HF, Kummer B, Putz RV (eds). Wolf-Heidegger's Atlas of Human Anatomy. Basel, Switzerland: Karger, 1990; with permission.)

The lymphatic drainage of the pharynx varies depending on the anatomic level. The posterior drainage is through the retropharyngeal lymph nodes (nodes of

Rouvier), located behind the pharynx at the level of the carotid bifurcation. Drainage of the lateral pharyngeal structures is to the jugulodigastric and

midjugular lymph nodes in the deep jugular chain (Fig. 13-26).

SURGICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Zenker's diverticulum (Fig. 13-32) may form in the area of Killian's dehiscence (Fig. 13-29), an area of weakness between the inferior constrictor muscle and

the fibers of the cricopharyngeus muscle. It is usually on the left side. This is a pulsion diverticulum. It results from increased intraluminal pharyngeal

pressures above the level of the cricopharyngeus and increased cricopharyngeal muscle pressures. This causes a gradual weakening of this area and

herniation of mucosa and submucosa through the weakened area to form a diverticulum. This problem is usually remedied by performing a cricopharyngeal

myotomy with or without resection or suspension of the herniated mucosa.

Fig. 13-32.

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 32/40

Zenker's diverticulum.

Oropharynx

The oropharynx is a continuation of the oral cavity anteriorly, the nasopharynx superiorly, and the laryngopharynx inferiorly (Fig. 13-8). It is located at

approximately the level of the 2nd and 3rd cervical vertebrae. Its boundaries extend superiorly from the junction of the hard and soft palate (Fig. 13-8, 13-

16) to the inferior margin at the level of the plane of the hyoid bone. Anteriorly, it extends to the junction of anterior and posterior regions of the tongue at

the level of the circumvallate papillae (Fig. 13-16).

The oropharynx contains the:

Soft palate and uvula

Palatine tonsils and tonsillar fossae

Base of tongue

Valleculae

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 33/40

Lateral and posterior oropharyngeal walls

SOFT PALATE

The soft palate (Figs. 13-8, 13-16, 13-30) is an essential muscular structure which extends from the level of the hard palate (Fig. 13-8) anteriorly to a

midline protuberance, the uvula, posteriorly. Laterally, the soft palate blends with the tonsillar area. The soft palate prevents nasopharyngeal reflux of air

and food by closing off the oropharynx from the nasopharynx during speech and swallowing.

The soft palate is composed of stratified squamous mucosa which covers a muscular framework of the following five muscles:

Levator veli palatini

Tensor veli palatini

Musculi uvulae

Palatoglossus

Palatopharyngeus

Except for the tensor veli palatini, these muscles are innervated by the vagus nerve to the pharyngeal plexus.

The levator veli palatini muscle (Figs. 13-17, 13-30) forms most of the bulk of the soft palate. It arises from the floor of the petrous portion of the temporal

bone and medial portion of the cartilaginous eustachian tube, medial to the pharyngobasilar fascia. It travels inferomedially in an oblique fashion to fuse with

the contralateral muscle in the posterior portion of the soft palate.

The tensor veli palatini muscle (Fig. 13-17) is the only soft palate muscle innervated by the mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve rather than the vagus

nerve. It arises from the medial pterygoid plate (Fig. 13-14), spine of the sphenoid bone, and lateral portion of the cartilaginous eustachian tube, lateral to

the pharyngobasilar fascia. It descends inferiorly to hook around the hamulus of the pterygoid bone (Fig. 13-30) and extends medially as a narrow tendon

to insert on the posterior hard palate as the palatine aponeurosis. This muscle functions to laterally tense the palate and also to open the eustachian tube

orifice. Children with cleft palates have poor function of the tensor veli palatini muscle, due to the muscle's midline dehiscence. This results in poor

eustachian tube opening and chronic middle ear effusions. The eustachian tube dysfunction improves after palatal surgical repair.

The musculi uvulae (Figs. 13-17, 13-30) arise from the posterior hard palate and palatine aponeurosis on each side of the midline, extend posteriorly, and

fuse as they form the uvula (Fig. 13-17). These function to draw the uvula upward and forward. Bifidity or notching of the uvula due to failure of these

muscles to fuse indicates a submucous cleft of the palate. Care should be taken when performing adenoidectomy to avoid postoperative velopharyngeal

insufficiency. Palpation of the palate is necessary to insure absence of submucous clefting even in the absence of a notching of the uvula.

The palatoglossus muscle (Figs. 13-30, 13-33) forms the anterior tonsillar pillar, creating the anterior border of the tonsillar fossa and demarcating the

anterior margin of the lateral oropharynx. It is a thin muscle arising from the inferior portion of the soft palate where it fuses to the contralateral

palatoglossus muscle, and projects inferiorly to attach to the lateral and dorsal tongue. It functions to draw the palate down and to narrow the pharynx.

Fig. 13-33.

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 34/40

Bed of the palatine tonsil. (Modified from Hollinshead WH. Anatomy for Surgeons. New York: Harper & Row, 1968; with permission.)

The palatopharyngeus muscle (Figs. 13-17, 13-30, 13-33) forms the posterior tonsillar pillar and part of the posterior portion of the tonsillar fossa. It arises

as two heads from the hard palate and palatine aponeurosis and more posteriorly from the contralateral palatopharyngeus muscle. The muscle inserts on

the fascia of the lower constrictor muscles. In addition to elevating the pharynx, the palatopharyngeus muscles function to draw the palate down and to

narrow the pharynx.

Blood supply of the soft palate is from the lesser palatine arteries (Fig. 13-25) and branches of the maxillary artery, which travel with the nerve though the

lesser palatine foramen. Sensory innervation is through the lesser palatine branches of the maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve.

TONSILS (PALATINE TONSILS)

The palatine tonsils (Figs. 13-8, 13-10, 13-16, 13-17), commonly referred to as the tonsils, are lymphatic structures containing indentations called crypts.

The tonsils reside in the tonsillar fossa, which is bounded anteriorly by the palatoglossal arch (Fig. 13-16) and posteriorly by the palatopharyngeal arch. The

arches contain the muscles of their corresponding names and are also referred to as the anterior and posterior tonsillar pillars, respectively (Fig. 13-33).

The tonsillar fossa is bounded superiorly by the soft palate, and inferiorly by the base of tongue mucosa. Tonsillar tissue frequently extends superiorly and

inferiorly into these structures.

Laterally, the tonsil has a capsule that is formed by the pharyngobasilar fascia. A layer of loose connective tissue separates the capsule from the superior

constrictor muscle. This potential space is the peritonsillar space. Spread of infection from the tonsils into this area results in a peritonsillar abscess,

requiring transoral aspiration or incision and drainage. Due to the proximity of the medial pterygoid muscle to the peritonsillar space (the medial pterygoid

muscle is located lateral to the superior constrictor muscle) (Fig. 13-18), peritonsillar abscesses present with trismus and bulging of the tonsil and soft

palate medially and inferiorly.

The inferior pole of the tonsil lies at the level of the interspace between the superior and middle constrictor muscles (Figs. 13-16, 13-18). Extension of a

peritonsillar abscess laterally in this interspace through the buccopharyngeal fascia results in a parapharyngeal space abscess (Fig. 13-34). This results in

more intense trismus because of the direct irritation of the medial pterygoid muscle. This also places the great vessels of the neck at risk due to their

location in the parapharyngeal space. Inferior dissection of infection through the carotid sheath may result in mediastinitis. The glossopharyngeal nerve

(Figs. 13-33, 13-34) also traverses this interspace between the superior and middle constrictor muscles at the inferior pole of the tonsil and is at risk in

deep dissection during a tonsillectomy.

Fig. 13-34.

The vascular supply of the palatine tonsil. (Modified from Hollinshead WH. Anatomy for Surgeons. New York: Harper & Row, 1968; with permission.)

Five branches of the external carotid artery system supply blood to the tonsils. The main supply is inferiorly from the tonsillar branch of the facial artery

(Fig. 13-34). The ascending pharyngeal, dorsal lingual, ascending palatine branch of the facial artery, and descending palatine artery also supply the

tonsils. Lymphatic drainage of the tonsils is primarily to the jugulodigastric lymph nodes (Fig. 13-26).

Sensory innervation of the tonsil is through the glossopharyngeal nerve and from the greater and lesser palatine branches of the maxillary branch of the

trigeminal nerve (Fig. 13-25). The phenomenon of referred otalgia (Fig. 13-35) in cases of tonsillitis, tumors of the tonsil, and after tonsillectomy is

mediated through common projections of the oropharyngeal fibers of the glossopharyngeal nerve and Jacobsen's nerve. Jacobsen's nerve (Figs. 13-24, 13-

35) is the tympanic branch of the glossopharyngeal nerve that innervates the middle ear mucosa.

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 35/40

Fig. 13-35.

Pathway of referred otalgia from the oropharynx. (Modified from DeSanto LW, Thawley SE, Genden EM. Treatment of tumors of the oropharynx: Surgical Therapy.

In: Thawley SE, Panje WR, Batsakis JG, Lindberg RD, eds. Comprehensive Management of Head and Neck Tumors, 2nd Ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1999; with

permission.)

BASE OF TONGUE

The base of tongue (Fig. 13-17) is the posterior one-third of the tongue which lies posterior to the circumvallate papillae (Fig. 13-16) and foramen cecum,

the area of origination of the thyroid gland. It extends posteriorly to the level of the valleculae, and laterally continues with the floor of mouth mucosa at

the inferior pole of the tonsils (Fig. 13-8). The base of tongue contains submucosal lymphatic collections referred to as lingual tonsils, which, together with

the palatine tonsils and adenoids (pharyngeal and tubal tonsils), form the previously described Waldeyer's ring (Fig. 13-10), a first line of immunologic

defense. This is also an uncommon area of primary lymphoma presentation.

The sensory innervation of the base of tongue is through the glossopharyngeal nerve, which supplies general visceral afferent fibers and special visceral

afferent fibers for taste. Base of tongue musculature is innervated by the hypoglossal nerve (Fig. 13-24). Arterial supply of the base of tongue is through

the lingual arteries. The base of tongue has a rich lymphatic drainage system primarily to the jugulodigastric lymph nodes (Fig. 13-26). Lymphatic drainage

to both sides of the neck is the rule. This necessitates addressing both the ipsilateral and contralateral neck when treating tumors of the base of tongue,

due to the likelihood of bilateral metastases.

The base of tongue extends posteriorly into paired concavities (valleculae) along the base of the lingual surface of the epiglottis (Figs. 13-8, 13-16). The

valleculae are separated in the midline by a median glossoepiglottic fold and bounded laterally by lateral glossoepiglottic folds (pharyngoepiglottic folds) (Fig.

13-16), which attach the epiglottis to the base of tongue.

The remainder of the oropharynx consists of the posterior pharyngeal wall and lateral pharyngeal wall posterior to the posterior tonsillar pillar.

Laryngopharynx (Hypopharynx)

The laryngopharynx is the longest section of the pharynx, extending from the level of the hyoid bone (Fig. 13-8) superiorly to the inferior border of the

cricoid cartilage at the level of the sixth cervical vertebra. It is wider superiorly and narrows inferiorly. The upper part of the laryngopharynx is the most

caudal portion of the common aerodigestive tract. The lower part, including the piriform recessses and postcricoid area, is the beginning of the separated

digestive tract that leads to the esophagus. The laryngopharynx is divided into the following three separate areas (Fig. 13-16):

Posterior pharyngeal wall

Piriform recesses

Postcricoid area

The posterior pharyngeal wall extends from the level of the hyoid bone to the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage and is continuous laterally with the

lateral wall of the piriform recesses.

The piriform recessses are funnel-shaped structures that are open posteriorly to the remainder of the pharynx. They are bounded anteriorly and laterally by

the lamina of the thyroid cartilage, and medially by the aryepiglottic fold, arytenoid cartilage, and cricoid cartilage (Fig. 13-8). The superior extent is at the

level of the pharyngoepiglottic fold (Figs. 13-16, 13-17), and the inferior apex is at the level of the cricopharyngeus muscle (Figs. 13-29, 13-32). This apex

approximates the level of the laryngeal ventricle.

The postcricoid area includes the mucosa covering the area from the posterior cricoarytenoid joint superiorly to the inferior border at the cricoid cartilage

(Fig. 13-8). It is continuous laterally with the medial wall of the piriform recessses and inferiorly with the esophagus.

Sensory innervation of the laryngopharynx is from the glossopharyngeal (Fig. 13-24) and vagus nerves. The posterior pharyngeal wall is innervated by the

fibers of the glossopharyngeal nerve through the pharyngeal plexus. The piriform recessses and postcricoid mucosa are innervated by the internal branch of

the superior laryngeal nerve, which runs beneath the mucosa of the anterior piriform recess. Anesthesia of the piriform recesses and larynx can be obtained

by topically anesthetizing the piriform recess mucosa or by percutaneous superior laryngeal nerve block at the thyrohyoid membrane (Fig. 13-28). The

laryngopharynx is surrounded by the inferior constrictor muscle (Figs. 13-18, 13-28). Motor innervation to this muscle is supplied by the external branch of

5/24/2014 Print: Chapter 13. Pharynx

http://web.uni-plovdiv.bg/stu1104541018/docs/res/skandalakis' %20surgical%20anatomy%20-%202004/Chapter%2013_%20Pharynx.htm 36/40

laryngopharynx is surrounded by the inferior constrictor muscle (Figs. 13-18, 13-28). Motor innervation to this muscle is supplied by the external branch of

the superior laryngeal nerve, which runs along the lateral border of the inferior constrictor muscle (Fig. 13-24) with the superior thyroid vascular pedicle.

Previously described, the vascular supply to the laryngopharynx is through the superior and inferior thyroid arteries and their branches (Fig. 13-24). The

lymphatic drainage is through the thyrohyoid membrane to jugulodigastric and midjugular lymph nodes (Fig. 13-26), but also involves the