Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Smith, Part 2, 2009, Pipeline Programs in The Health Professions

Загружено:

Jesse M. MassieИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Smith, Part 2, 2009, Pipeline Programs in The Health Professions

Загружено:

Jesse M. MassieАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

852 JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION VOL. 101, NO.

9, SEPTEMBER 2009

O R I G I N A L C O M M U N I C A T I O N

BACKGROUND

T

he laws of the United States and corresponding

legislative action, such as affirmative action,

have always played an integral role in expanding

equal opportunity and access in education, health care,

housing, and in opening doors within the democratic

institutions of American society.

1

However, in the last

2 decades, the need for the continuation of affirmative

action programs, particularly in education, has been

under intense scrutiny in the courts and the topic of state

voter initiatives or legislative action in Florida, Texas,

California, Michigan, and Washington.

2

In conjunction

with the November 2008 elections, efforts to outlaw the

use of race, ethnicity, sex, and national origin in pub-

lic education programs have been the subject of intense

debate and antiaffirmative action campaigns targeted

at Arizona, Oklahoma, Missouri, Nebraska, and Colo-

rado.

3

Referred to as the Super Tuesday of equality by

state voter-sponsored initiative proponents lobbying to

remove affirmative action in public education program-

ming, including student pipeline programs, these ballot

initiatives managed to only make their way onto the bal-

lots in Colorado and Nebraska.

4,5

On November 4, 2008, Colorado became the rst

state to defeat the state-sponsored antiafrmative

action voter initiative known as Amendment 46. How-

ever, with passage of Initiative 424 in Nebraska, the

ability to ensure diversity in the public workforce and

educational sectors faces new challenges.

6,7

In particular,

the University of Nebraska Medical Center, other cam-

puses in the University of Nebraska System, heavily

Author Affiliations: Health Services Research & Administration (Dr Smith,

associate vice chancellor for academic affairs, chief student affairs officer,

associate professor), Internal Medicine-Pediatrics (Dr Nsiah-Kumi, assistant

Background: Despite recent challenges to educational

pipeline programs, these academic enrichment programs

are still an integral component in diversifying the health pro-

fessions and reducing health disparities. This is part 2 of a 2-

part series on the role of pipeline programs in increasing the

number of racial and ethnic minorities in the health profes-

sions and addressing related health disparities. Part 1 of this

series looked at the role of pipeline programs in achieving a

diverse health professional workforce and provided strate-

gies to expand pipeline programs.

Methods: This paper presents an historical overview of affir-

mative action case law, antiaffirmative action legislation,

and race-conscious and race-neutral admission programs in

education. Additionally, part 2 reviews current legal theory

and related law that impact the diversity and cultural com-

petence pipeline programming at higher-education institu-

tions. Finally, based on recommendations from a review of

legal and other literature, the authors offer recommenda-

tions for reviewing and preserving diverse pipeline programs

for health professional schools.

Conclusion: Affirmative action is an essential legal means

to ensure the diversity-related educational programs in the

health profession educational programs. Antiaffirmative

action legislation and state-sponsored antiaffirmative voter

initiatives have the potential to limit the number of under-

represented minorities in the health professions and create

even greater opportunity gaps and educational disparities.

Therefore, we must shift the paradigm and reframe the dia-

logue involving affirmative action and move from debate to

a collaborative discussion in order to address the historical

and contemporary disparities that make affirmative action

necessary today.

Keywords: health disparities n children/adolescents n

minorities n education

J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101:852-863

Pipeline Programs in the Health Professions,

Part 2: The Impact of Recent Legal Challenges

to Affirmative Action

Sonya G. Smith, EdD, JD; Phyllis A. Nsiah-Kumi, MD, MPH; Pamela R. Jones, PhD, MPH, RN;

Rubens J. Pamies, MD, FACP

professor), Community-Based HealthCollege of Nursing, Health Promo-

tion, Social and Behavioral HealthCollege of Public Health (Dr Jones,

assistant professor), University of Nebraska Medical Center (Dr Pamies, vice

chancellor for academic affairs, dean of graduate studies, professor of

medicine), Omaha, Nebraska.

Corresponding Author: Sonya G. Smith, EdD, JD, Associate Vice Chancel-

lor for Academic Affairs, Chief Student Affairs Officer, Associate Profes-

sor, Health Services Research & Administration, University of Nebraska

Medical Center, 984250 Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE 68198-4250

(sonyagsmith@unmc.edu).

JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION VOL. 101, NO. 9, SEPTEMBER 2009 853

PIPELINE PROGRAMS AND RECENT LEGAL CHALLENGES

populated underrepresented minority (URM) communi-

ties, and concerned citizens, eager to address the dispro-

portionate number of students of color entering medical

schools and the health care professions, are looking to

other states where similar antiafrmative action legis-

lation has passed in order to discern the possible impact

and develop lawful diversity initiatives.

8

In light of such current political action and ongoing

assaults on equal-access P-16 pipeline programs, it is

imperative to review the history of afrmative action

law in America and discuss the impact of recent chal-

lenges aimed at diversity programs to increase URMs in

the health professions. As asserted in part 1, pipeline

programs are an effective strategy for increasing the rep-

resentation of racial and ethnic minorities in the health

professions and reducing health disparities. A discus-

sion of pipeline programs, particularly those dedicated

to improving the number of URMs in medicine, is pro-

vided in greater detail in the rst part of this series.

To fully appreciate the impact of this type of legisla-

tion on P-16 pipeline programs and other projects

designed to increase diversity in the health professions,

we begin with a review of afrmative action legislation

and subsequent antiafrmative action laws in America.

These laws are discussed in the context of equal oppor-

tunity legislation, US Supreme Court education, and

afrmative action case law, state postsecondary percent-

age plans, and state-sponsored voter initiatives affecting

public education. Additionally, because data are readily

available in California, a review of the impact of the

antiafrmative action ballot initiative on Californias

college and universities higher-education admissions is

provided. Finally, despite the dissension surrounding

antiafrmative programming, recommendations related

to furthering diversity pipeline programs in the health

professions are also included. However, these recom-

mendations should not be construed as legal advice on

behalf of any of the authors. Additionally, as stated in

part 1, afrmative action, for purposes of this article, is

dened as programs, policies, laws, and strategic plans

designed to increase the number of historically under-

represented and disadvantaged groups who have con-

fronted unlawful societal discrimination in education,

employment, government, and other areas.

AN OVERVIEW OF

AFFIRMATIVE ACTION AND

EQUAL-OPPORTUNITY LAW

Many of the issues of educational access and increas-

ing the health professional pipeline have evolved from

antidiscrimination and afrmative action case law

and legislation in the employment context, federal con-

tracting, and educational arena. Antidiscrimination laws

stressed the importance of nondiscrimination employ-

ment and federal government contracting, particularly in

relation to race, color, and national origin.

9

Closely tied

to antidiscrimination laws is afrmative action legisla-

tion, which requires employers and businesses to take

afrmative steps with the regard to race, sex, national

origin, and color in federal contracting and the fair hir-

ing and creation of equal employment opportunity.

9

However, the rst use of the term afrmative action

was in the 1960s by President John F. Kennedy in sev-

eral executive orders focusing on antidiscrimination

laws and calling for equality

10

in reference to an equal

opportunity policy designed to improve integration in

federally nanced work projects.

11

Although in 1941

President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued the rst execu-

tive order8802

12

outlawing antidiscrimination mea-

sures in employment by private employers contracting

with the federal government above a specic monetary

amount, almost every US president has reissued or

revised these orders.

In 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson issued Execu-

tive Order 11246,

13

forbidding discrimination on the

basis of race, color, national origin, and religion. It was

later amended in 1967 to outlaw sex discrimination.

14

Additionally, President Richard Nixon issued Executive

Order 11478, prohibiting discrimination in federal

employment on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or

national origin.

15

Other amending executive orders were

issued by Presidents Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton.

President Carter added handicap and age as protected

classes in terms of employment discrimination and, in

1998, President Clinton, under Executive Order 13087,

made sexual orientation discrimination unlawful in fed-

eral employment.

16,17

During the 1970s, antidiscrimina-

tion laws and afrmative action policy were expanded to

include postsecondary admission programs.

11

Equally,

afrmative action plans were put in place as race- and/or

sex-specic plans designed to provide a remedy for pres-

ent and persistent effects of historical discrimination

against African Americans and women, along with any

effects of discrimination motivated by unconscious

biases and stereotypes

18

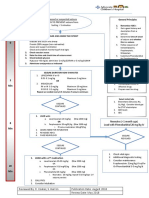

(Figure 1).

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which for-

bids public and private employers, labor organizations,

and employment agencies from discriminating in the

workplace on the basis of race, color, sex, religion, and

national origin, is among the most signicant civil rights

and antidiscrimination legislation. However, it does not

use the phrase afrmative action.

10,18,19

The most impor-

tant amendments to Title VII came in 1972, extending

coverage to not only federal and state governments, but

also to local governments.

18

The Fourteenth Amendment

20

of the US Constitution also provides protection under the

due process and equal protection clauses, which makes it

unlawful for states and municipalities to discriminate.

18

In the same way, Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of

1964 makes it unlawful to discriminate on the basis of

race, color, or national origin in any program or activity

which receives federal nancial assistance.

21

This

854 JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION VOL. 101, NO. 9, SEPTEMBER 2009

PIPELINE PROGRAMS AND RECENT LEGAL CHALLENGES

includes K-12 and postsecondary institutions receiving

federal grants, participating in federal student loan pro-

grams, and obtaining federal contracts.

18

Additionally,

states receiving federal Medicaid and Medicare dollars

are covered by antidiscrimination legislation such as

Title VI.

22

Likewise, Title IX of the Educational Amend-

ments of 1972 prohibits sex discrimination in any edu-

cational program or activity receiving federal nancial

assistance.

18,23

Therefore, if any student or faculty mem-

ber receives federal grants or loans, public and private

postsecondary institutions must comply with Titles VI,

VII, and IX civil rights legislation (Figure 1).

Both antidiscrimination laws and afrmative action

legislation have major implications for the implementa-

tion, design, and maintenance of academic readiness,

outreach, and medical school pipeline programs. Most

afrmative action litigation and policy development has

been specically directed at the legality of race-specic

college admissions criteria.

24-26

Nevertheless, an out-

growth of antidiscrimination and afrmative action laws

has been the use of afrmative action in the context of

college admissions and higher-education diversity. As

time progressed, more colleges and universities started

to apply afrmative action in new ways in order to not

only diversify faculty and staff but the student body.

Nevertheless, afrmative action continued to be contro-

versial and criticized as watering down the application

pool, and opponents of afrmative action charged that

less-qualied minorities and women were admitted in

place of more-qualied white students.

27-29

In response to this criticism, higher-education insti-

tutions devised new pipeline and preprofessional pro-

grams as a further outgrowth of afrmative action prin-

ciples to increase the success of racial and ethnic

minorities and women in the admissions process, and

improve academic readiness for graduate and medical

schools. Traditionally, due to lack of social capital, seg-

regation and discrimination, and inequality in nancial

resources, these groups were denied access to educa-

tional opportunities and equal protection under the

law.

1,30

These new pipeline and preprofessional programs

provide minorities and women with improved academic

preparation and skill sets required for success.

THE US SUPREME COURT

EQUAL OPPORTUNITY EDUCATION

CASE LAW

The quest for educational equality began with the

landmark ruling, Brown v Board of Education in 1954,

declaring that separate but equal was no longer the

law of the land in terms of segregated black and white

public schools.

30

Following this landmark case was

Regents of the University of California v Bakke (Bakke),

striking down the University of California medical

schools 2-tiered admissions policies, including setting

aside admission spots for African Americans and

enabling the white applicant who brought the case to be

admitted.

31

Because the medical school had 16 set-asides

for minority students in the entering class, Bakke, a

white candidate for admission, claimed that the univer-

sitys medical school had unlawfully denied him admis-

sion under the Equal Protection Clause and Title VI of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

31

Most notably, Bakke stands for the proposition that

achieving a diverse student body in academia is a suf-

ciently compelling state interest; thus, the consider-

ation of race and ethnicity, among many other factors, is

a constitutionally legitimate means of achieving this

goal.

31

Other possible diverse admission factors asserted

by the Court were talents, economic background, inter-

est, and geographical region.

31

Bakke further outlawed specic set-asides, quotas,

and separate admission tracks for racial and ethnic groups

in admissions but permitted universities under the Four-

teenth Amendment to voluntarily establish admissions

programs based on racial preferences to remedy past dis-

crimination.

31,32

Under the Courts ruling, all race-con-

scious admissions programs were subject to the most rig-

orous legal test, strict scrutiny.

31

The strict scrutiny test

requires that the state show (1) it has a compelling inter-

est in its race/ethnicity-based program or policy deci-

sion in order to achieve a mission such as the educational

benets of diversity; (2) the race/ethnicity-conscious

program and/or policy decision is necessary to address

issues of equal opportunity consistent with the university

mission and education focus, after having evaluated race

neutral alternatives; (3) the race-conscious program or

policy is reasonably limited in time and scope; and (4) a

narrowly tailored means is used to achieve the states

compelling interest.

2,31,33,34

The compelling state interest portion of the strict

scrutiny legal standard has 2 prongs. The government

must be able to show that its reason for considering race

as a factor is not based on prejudice or racial animosity

but is intended to serve a legitimate and highly substan-

tial government interest. Finally, the race-based policy

and/or decision must also be necessary to either achieve

or protect the compelling interest such as the educa-

tional benets of diversity

32,34

(Figure 2).

In looking at whether a race/ethnic-based admissions

program is narrowly tailored, the Court will look at a

public universitys diversity program, which is the means

it is using to achieve a compelling state interest, such as

the educational benets of a diverse student body, to see

(1) if there is a precise t in which race and ethnicity are

considered in a limited manner; (2) the necessity of using

race/ethnicity to achieve an end goal, such as the educa-

tional benet of a diverse student body; (3) the exibility

of the race-based program; (4) the burden placed on the

racial/ethnic nonbeneciaries of the program; and (5) if

there is an end point to the race/ethnic-based program.

2,33-

35

Although Bakke remains one of the major cases by

JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION VOL. 101, NO. 9, SEPTEMBER 2009 855

PIPELINE PROGRAMS AND RECENT LEGAL CHALLENGES

Figure 1. Key Affirmative Action Events and Antidiscrimination Laws

856 JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION VOL. 101, NO. 9, SEPTEMBER 2009

PIPELINE PROGRAMS AND RECENT LEGAL CHALLENGES

which the constitutionality of race-conscious admissions

programs is judged, even after 1978, the lower federal and

state courts continued to be divided regarding the consti-

tutional viability and the meaning of the legal standard for

the use of race set forth in Bakke.

31,36-39

In 2003, the US Supreme Court joined 2 cases and

handed down a set of historical rulings that would also

forever shape the landscape of diversity in higher educa-

tion. Factually, in the 2 cases, Grutter v Bollinger et al

(Grutter) and Gratz et al v Bollinger et al (Gratz), 2 white

students alleged that they, respectively, had been denied

admission to the University of MichiganAnn Arbor law

school and undergraduate program in violation of the

equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of

the US Constitution, Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, and 42 USC 1981.

40,41

The Court upheld the law-

fulness of the University of Michigan law schools admis-

sions policy, but because the undergraduate policy was

not sufciently narrowly tailored, 6 of the justices

found the undergraduate admissions policy unlawful.

40,41

Writing for the majority in Grutter, Justice OConnor,

relying on the strict scrutiny test triggered by race/eth-

nicity-based programs, reafrmed that public educational

institutions seeking diversity must do so in a narrowly

tailored form but also agreed with Bakke that the rele-

vant context mattered and not every decision inuenced

Figure 2. Strict Scrutiny Legal Standard and Race-Conscious Policies and Programs

JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION VOL. 101, NO. 9, SEPTEMBER 2009 857

PIPELINE PROGRAMS AND RECENT LEGAL CHALLENGES

by race was equally objectionable.

37,41

Importantly, the

US Supreme Court deferred to the University of Michi-

gans assessment that diversity was essential to its mission

and that, as Justice Powell had written in the Bakke opin-

ion, student body diversity is a compelling state interest

that could justify the use of race in university admis-

sions.

37,41

The Court also held that the law school did not

violate the law by seeking to enroll a critical mass of

minority students and that some attention to numbers

could be paid without constituting a quota system.

37,41

Specically, the Court in Grutter not only agreed that

higher-education diversity could serve as a compelling

state interest but agreed that the University of Michigan

law schools admissions policy, which included race as a

plus in its holistic and individualized review of appli-

cants based on many factors, was narrowly tailored under

strict scrutiny, as Justice Powell had laid out in Bakke.

40,41

In contrast, the Court, in Gratz, struck down the Univer-

sity of Michigans undergraduate admissions point-based

afrmative action policy selection index due to its

inability to provide an individualized evaluation of the

applicants les, which violated narrowly tailoring and

operated very similar to the quota system in Bakke.

40,41

The major implication for the Gratz and Grutter cases

is that whether a race/ethnicity-based public education

policy or program will be held lawful depends upon how

it is applied (Figure 1). Therefore, some confusion still

exists about the application of race/ethnicity-based poli-

cies and programs in public education and how to suc-

cessfully implement them in a lawful context.

37

Two new cases focusing on race-based admissions

programs came before the US Supreme Court in 2007.

These cases were Parents Involved in Community Schools

v Seattle School District No. 1 (Seattle) and Meredith v

Jefferson County Board of Education (Louisville)

42,43

(Figure 1). The Seattle and Louisville cases were decided

in June 2007 and were not cases involving remedies of

dejure or past desegregation. The Louisville case involved

a white plaintiff in Louisville, Kentucky, whose son had

been denied a transfer to attend kindergarten in the Jef-

ferson County Public Schools, which had adopted a race-

conscious school assignment plan. Under this plan,

schools were to seek black student enrollments between

15% and 50%, a target based on the demographics of the

public schools in the county.

42-44

In the Seattle case, the Seattle school district embraced

an open choice plan for 10 high schools, and 5 of the 10

high schools were usually overly requested. Students

wishing to attend overly requested high schools were

assigned to these schools based on 4 tiebreakers: (1) a

preference for keeping siblings in the same school, (2) an

integration tiebreaker, (3) distance from home to school,

and (4) a lottery system.

42-44

If 1 of the 5 oversubscribed

high schools had a racial imbalance, dened as white and

nonwhite enrollments, not within 10 percentage points of

the school districts demographics, the integration tie-

breaker was utilized.

42-44

Specically, African American

students were classied as blacks and all other non-

white students were placed together in a category called

other. Comparing racial variances within the schools

student body composition and percentages of all students

in the district as part of their decision making process, the

Seattle school district focused on racial imbalances in

order to attempt to bring high schools closer to a 60%

nonwhite and a 40% white balance.

42-44

Because both the school districts in the Louisville

and the Seattle cases employed race-conscious policies,

this triggered evaluation under the strict scrutiny stan-

dard, thereby requiring each district to demonstrate that

the policies were narrowly tailored to promote a compel-

ling governmental interest.

44

Specically, race-conscious

policies: 1) explicitly use racial classications as a fac-

tor in evaluating a candidates admission to an educa-

tional program, and 2) may be policies that appear to be

racially neutral on their face, but the motive for utilizing

the policy is indeed discriminatory.

45

Importantly, it must be noted that the two school dis-

tricts in the Louisville and Seattle cases were not pursuing

these race-based or race-conscious plans to further the edu-

cational benets of diversity, nor did the plans involve a

holistic review of factors for admission such as students

talents or socio-economic background. In other words,

diversity was dened solely by race and ethnicity.

42-44

Because the districts did not prove that the use of

race was necessary to achieve their prescribed goals and

that each had not considered race-neutral alternatives,

the Court ruled that neither of the districts had satised

the strict scrutiny legal standard. However, based on

these cases, race and ethnicity can still be used as 1 of

multiple factors in admissions.

42

Nevertheless, the Louisville and Seattle cases demon-

strate that despite Grutter, in public educational institu-

tions and related pipeline programming, caution must be

exercised in attempts to establish a critical mass of

minority students.

46

It is important to note that most legal

scholars agree the achievement of a critical mass is

still somewhat illusive terminology and needs further

clarication from the Court.

32,33

For example, a critical

mass of URM can include a clearly stated objective but

not operate as a rigid quota system. The Grutter Courts

reference to critical mass theory incorporated students

of color in terms of (1) meaningful numbers, (2)

meaningful representation, (3) a number that encour-

ages underrepresented minority students to participate in

the classroom and not feel isolated, (4) students from

groups which have been historically discriminated

against, (5) individuals who are likely to have experi-

ences and perspectives of special importance to the [edu-

cational institutions] mission, and (6) minority students

who do not feel like they must be spokespersons for their

race or ethnic group nor feel uncomfortable discussing

experiences that may differ from the majority.

2,33,34,41

858 JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION VOL. 101, NO. 9, SEPTEMBER 2009

PIPELINE PROGRAMS AND RECENT LEGAL CHALLENGES

Furthermore, critical mass must be linked directly

to the educational benets of diversity that the educa-

tional institution or medical school has as its mission.

2,41

Additionally, race-neutral alternatives must be consid-

ered, and educational institutions must solidly dene

their missions and educational objectives in relationship

to the role that diversity and/or cultural competence

plays in achieving their goals and missions.

44

Race can-

not be a deciding factor in admission to public educa-

tional programs. A holistic review of all applications

that incorporates other factors must occur.

41,46

It should be noted that there is not a specic body of

equal opportunity or afrmative action case law that

addresses the admission/selection of racial and ethnic

minorities to precollege, outreach, pipeline, or preprofes-

sional admissions programs. The US Department of Edu-

cation refers to these Bakke-like programs as develop-

mental approaches or approaches designed to diversify

student enrollments by enriching the pipeline of appli-

cants equipped to meet entry requirements and achieve

academic success.

47

However, higher-education ofcials

and attorneys have long assumed that Gratz and Grutter

apply to many different kinds of race-based admission

policies and programs, such as pipeline and precollege,

that consider Bakke-like race and ethnicity factors.

48,49

For example, as Calleros notes

Race-neutral developmental approaches could

encompass any race-neutral measures designed

to increase the number and quality of diverse

applicants who make their way into the applica-

tion pipeline. These might include governmental

measures to improve K-12 education, especially

in schools or districts that have fallen behind in

academic success, as well as private or govern-

mental outreach measures to encourage a broad

spectrum of students to aspire to higher educa-

tion and to apply for admission.

49

Calleros further states that

Even if schools more consciously target minority

groups with their outreach efforts, race-conscious

efforts to enhance diversity in the applicant pool

likely will be subject to less searching review than

race-conscious decisions that result in actual

admission. Moreover, developmental programs

are an important supplement to race-conscious

admissions programs as well as a means of fur-

thering race-neutral admissions.

49

STATE-SPONSORED ANTIAFFIRMATIVE

ACTION VOTER INITIATIVES

Since 1996, state-sponsored voter initiatives have

sought to ban afrmative action in public education, pub-

lic contracting, and public employment in California,

Washington, Michigan, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Missouri,

Colorado, and Arizona.

3

Freedom from unlawful racial

and sexual discrimination requires measurable progress

goals and monitoring to alleviate historical unfair and

discriminatory treatment and opportunity gaps experi-

enced by women and minorities.

50

Therefore, state-spon-

sored voter initiatives seeking to displace afrmative

action programs and pipeline programs for URM stu-

dents have been placed in jeopardy by such measures.

Prior to 2008, antiafrmative action and/or anti

equal opportunity state voter initiatives had passed in 3

states: California (Proposition 209), Washington (Initia-

tive 200), and Michigan (Proposal 2).

51

The language of

these state-sponsored ballot initiatives is basically uni-

form in nature and very similar in that they seek to

remove what their proponents view as racial, ethnic,

national origin, and gender preferences from any pro-

grams associated with public education, public employ-

ment, or public contracting.

51

Sample language from

these state-sponsored ballot initiatives typically propose

a constitutional amendment or enactment of a statute

virtually banning most forms of afrmative action. An

example of the language is:

The state shall not discriminate against, or grant

preferential treatment to, any individual or group

on the basis of race, sex, color, ethnicity, or

national origin in the operation of public employ-

ment, public education, or public contracting.

51

Leading the charge for these state-sponsored ballot

initiatives is Ward Connerly, a businessman and former

regent of the University of California system and head of

the American Civil Rights Institute (ACRI).

52

The ACRI

sponsored November 2008 antiafrmative action ballot

initiatives in Arizona, Oklahoma, Missouri, Colorado,

and Nebraska.

3,7,51

Ballot initiatives only successfully

appeared on the Colorado and Nebraska 2008 ballots.

The ballot initiative failed in Colorado, thus ending its

political course, but passed in Nebraska.

7

The state with the longest history and most available

published data related to the poststate ballot initiative

impact is California. Due to the recent passage of the

antiafrmative action ballot initiatives in Michigan and

Nebraska, more time is needed in order to discern the

possible ramications in these 2 states. Additionally,

there are limited published and longitudinal data on the

impact of the antiafrmative action ballot on the health

professional schools for the state of Washington.

53

In California, substantial decreases in the number of

URM students in higher education have been devastat-

ing and have required innovative approaches to diversi-

fying the student body and maintaining educational

pipeline and enrichment programs. For example, after

the passage of Prop 209, the University of California

Berkeley saw a decline of 65% in minority student

JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION VOL. 101, NO. 9, SEPTEMBER 2009 859

PIPELINE PROGRAMS AND RECENT LEGAL CHALLENGES

enrollment, and the University of CaliforniaLos Ange-

les experienced a 45% decline in the matriculation of

students of color.

7

Additionally, data from the Association of American

Medical Colleges on minority admissions and matricu-

lation at California medical schools before and after

Prop 209 show decreases in the number of URMs who

are California in-state residents enrolling in MD pro-

grams.

54

California residents approved Prop 209 in 1996,

banning the use of race/ethnicity as factors in admis-

sions. Pre-Prop 209 medical school acceptance reveals

an acceptance of 233 minority residents to California

medical schools in 1993, compared to 157 in 1997, and

only 156 in 2001.

54

Likewise, the percentage of minority medical school

California residents studying in the state dropped from

23.1% in 1993 to 14.3% in 1997.

54

Consequently, the

percentage of Californias in-state minority residents

studying at state medical schools has averaged between

16.4%, a decrease of 6.7% as of the last decade.

54

Most

notably, since 1995, more than half of Californias

minority residents accepted to medical schools outside

the state have chosen to matriculate at non-California

medical schools.

54

One year after the passage of Washingtons I-200 in

1998, the University of Washington reported a one-third

drop in minority enrollment with African Americans con-

stituting 1.84%; American Indians, 0.91%; and Hispan-

ics/Latinos, only 2.9% of the entering class.

55

However, in

2004, minority enrollment at the University of Washing-

ton rose again to preI-200 levels, with African Ameri-

cans making up 3.04% of the freshmen class; American

Indians, 1.27%; and Hispanics/Latinos, 4.64%.

55

During

the passage of Proposal 2 in 2006, the University of Mich-

igan was in the middle of its admissions cycle; therefore,

the longitudinal impact of Prop 2 in Michigan is still

unclear. However, after its rst full admissions cycle since

approval of the ban, the University of Michigan has only

seen a 2% drop in minority enrollment.

7

STATE-SPONSORED PERCENTAGE PLANS

Although voter ballot initiative antiafrmative plans

have not been enacted in these states, both Florida and

Texas have implemented controversial percentage plans

as part of their efforts to move toward admissions race-

neutral. In November 1999, Jeb Bush, Floridas gover-

nor, issued Executive Order Number 99-281, eliminat-

ing the use of race, national origin, or sex in university

admissions, employment, and contracting, thereby abol-

ishing afrmative action in higher education and other

state agencies.

51,56

Former Governor Bushs executive

order was in response to Ward Connerlys attempt in

Florida at a state voter referendum that would end afr-

mative action policies, similar to Proposition 209 in Cal-

ifornia.

56

The Florida executive order was an extenuation

of the One Florida plan or the Talented 20, which guar-

anteed admission of the top 20% of all Florida high

school graduating students to 1 of Floridas 11 public

universities

57

(Figure 1).

As part of the Talented 20 plan, need-based nancial

aid was increased by 43%, or $20 million, in hopes of

increasing access for underrepresented students and

expanding diversity in the State University System

(SUS).

56

However, Florida high school graduates who

qualied received no guarantee of admission to the SUS

institution of choice.

Taking into consideration the entire Talented 20

applicant pool in 2001, fewer than half enrolled at a SUS

institution. Specically, 3 years after the implementation

of the Talented 20 plan, only 43.1% of eligible Hispanics

and 49.4% of eligible African American students

enrolled in the system in 2001.

56

Nevertheless, at the

University of Florida in 2000, the number of rst-time

college African Americans did increase from 9.8% in

1998 to 12.9%.

56

However, the number of rst-time Afri-

can Americans dropped signicantly to 9.4% at the Uni-

versity of Florida in 2001, while the proportion of His-

panics rose from 10.9% in 1998 to 12.1 in 2000 and held

steady in 2003.

56

Data from 2000 demonstrated that of the eligible Tal-

ented 20 students applying to SUS institutions, 95.5%

were accepted, but in 2001 only 81.9% were admitted. In

looking at African American Talented 20 applicants in

2000, 92.5% were accepted to SUS campuses but

accounted for only 72.1% in 2001.

After the 1996 Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals ruling

in Hopwood v Texas,

39

ending the use of race-conscious

admissions, Texas adopted a Top 10 plan. The Top 10

plan automatically admitted the top 10% of graduating

seniors in Texas, regardless of standardized test scores, to

any public college or university in the state. This plan

was signed into law by then Governor George W. Bush.

58

The Hopwood case involved 4 white students who

alleged that they were not admitted to the University of

Texas law school in violation of the Fourteenth Amend-

ments Equal Protection Clause. At the time, the Univer-

sity of Texas law school used an admissions process that

placed students into relative categories such as presump-

tive admit, discretionary, or presumptive denial. These

categories were based on a weighted index score consist-

ing of the candidates undergraduate grade point average

and Law School Admission Test (LSAT) score.

39

Under this procedure, Mexican American and Afri-

can American applicants could have lower index scores

and be presumptively admitted. The US Fifth Circuit

Court of Appeals ruled the law schools policy violated

the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amend-

ment and could not withstand strict scrutiny.

39

Signi-

cantly, this lower court, the Fifth Circuit Court of

Appeals, went even further and outlawed all race-con-

scious admissions policies, thus, rejecting the US

Supreme Courts ruling in Bakke.

39,58

860 JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION VOL. 101, NO. 9, SEPTEMBER 2009

PIPELINE PROGRAMS AND RECENT LEGAL CHALLENGES

In an attempt to offset Hopwood, the Texas Top 10

plan was implemented. Prior to Hopwood, whites made

up 64% of the total enrollment at the University of

TexasAustin (UT-Austin). Minorities represented 36%

of the universitys enrolment; African Americans, 5%;

and Hispanics, a little less than 15%.

59

However, in 1997,

minority enrollment at UT-Austin reached its lowest

decline since 1994, with African Americans accounting

for only 3% and Hispanics 13%.

59

Although the undergraduate minority enrollment con-

tinues to increase at UT-Austin, the percent of African

American admits and matriculants still needs much

improvement. In 2001, the number of African Americans

applying to UT-Austin increased by 24%, but the percent

admitted decreased by 19%.

59

In 2003 Grutter would over-

rule Hopwood and, as a result, allow the voluntary use of

race as a factor in a holistic admissions procedure.

41

It should be noted that in 1960 California adopted a

percentage plan for its colleges and universities.

60

The

plan, A Master Plan for Higher Education in California,

recommended that California State Colleges (currently

California State University) select rst-time freshmen

from the top one-third (33.3%) and the University of

California from the top one-eighth (12.5%) of all gradu-

ating California public high school students.

60

Additionally, as part of the University of California

policy on undergraduate admissions, California would

reafrm the importance of enrolling a culturally, racially,

geographically, and socioeconomically diverse student

body in May 1988.

60

Furthermore, during the 1980s,

University of California admission guidelines estab-

lished a 2-tier process in admissions, allowing campuses

to admit the top 40% to 60% of their rst-year freshmen

class solely on academic criteria and the remainder of

the class based upon a combination of academic and

supplemental criteria (nonacademic) such as commu-

nity service or special talents.

60

However, in 1995, and 1 year prior to the passage of

Prop 209 in California, the University of California

Board of Regents passed Special Regental Action Num-

ber 1 (SP-1) prohibiting the use of race, ethnicity, and

gender in admissions

61

(Figure 1). Additionally, SP-1

included a percentage plan allegedly aimed at ensuring

equal treatment by requiring that not less than 50% and

not more than 75% of any entering class on any campus

be admitted solely on the basis of academic achieve-

ment. In this case, academic achievement referred to

grades and standardized tests only.

61

After the passage of SP-1 in 1995, the number of

minority applicants applying to University of California

declined.

60

Specically, 22.1% of freshmen applicants

were minority students in 1995; however, these numbers

fell to 18.8% in 1998. SP-1 would be overturned by the

passage of Prop 209 in 1996, with the proposition taking

legal effect in 1998.

60

In February of 2009 the University of California

adopted another major change to its undergraduate

admissions policy.

62

The policy is likely to decrease the

percentage of California high school graduates who are

guaranteed places on at least 1 of the University of Cali-

fornia campuses, from approximately the top 12.5% to

the top 10%.

62

The policy also eliminates the 2 SAT sub-

ject tests. The goal of the University of California is to

move toward a more comprehensive admissions review

and enlarge its applicant pool.

62

University projection,

based on 2007 data, indicates that the new policy may

potentially decrease the number of admitted Asian Amer-

ican students while increasing the number of whites.

Nevertheless, university ofcials state that the new pol-

icy will improve the educational access of minority and

students from low socioeconomic backgrounds.

62

MAINTAINING THE PIPELINE:

STRATEGIES FOR OVERCOMING

CHALLENGES TO AFFIRMATIVE ACTION

As public colleges and universities struggle with liti-

gation and legislative initiatives challenging afrmative

action, it is essential that institutions do not abandon

their missions and goals related to diversifying the stu-

dent body and their commitment to developing pipeline

programs that will provide opportunities for URMs in

postsecondary education. As indicated in part 1 of this

series, medical professionals of color will be instrumen-

tal in resolving many of the economic and healthcare

disparities which challenge America.

Below are recommendations that K-16 educational

institutions, graduate and professional schools, health

care organizations, and policy makers should consider

in developing diversity pipeline programs to increase

URM students in the health professions as they undergo

afrmative action scrutiny.

Clearly affirm or reaffirm the institutional mission

and objectives to insure that diversity and cultural

competence are incorporated as core institutional

values.

2,35

Ensure there is a strong connection between the

benefits of educational diversity as a part of the

institutional core mission and universitywide

strategic plan objectives.

2

Incorporate strategic enrollment management,

which includes recruitment, retention, outreach,

marketing, alumni/advancement, as an integral part

of any diversity plan and align all strategies and

goals across departments and colleges.

If race-conscious or race-based admissions

procedures are utilized, make sure they are part of a

holistic plan which considers other factors such as

talents, interests, socioeconomic background, and

overcoming adversity.

Whether a diversity pipeline program is considered

race neutral has to do with the actual intent or

JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION VOL. 101, NO. 9, SEPTEMBER 2009 861

PIPELINE PROGRAMS AND RECENT LEGAL CHALLENGES

motive behind the program and/or admissions

policy. Therefore, consider inclusive outreach

marketing and race-neutral recruitment programs

which focus on:

academic qualificationsgrade point average,

test scores, evaluations, and rigor of course

work and academic major for candidates to

postsecondary institutions.

45

talents, interests, abilitiesgeographical

background, socioeconomic status, parental

education, first-generation college students

and/or professional students, cultural

competence/awareness, commitment to

working in underserved communities or

reducing health disparities, high school/

community demographics (both rural and

urban), participation in study abroad programs,

athletics, artistic ability or other talents, and

volunteer and employment experiences in

underserved communities and/or countries.

45

Align definitions of underrepresented minorities

with federal government language such as the US

Department of Health and Human Services in

describing shortages in medicine, biomedical field,

nursing, etc.

In designing P-16 pipeline programs to increase

URM students in the health professions, link

program and policy goals/mission to federal

objective programs such as those in the federal

Office of Minority Health objective.

Review race-based programs regularly and in doing

so, consider viable nonrace-based or race-neutral

alternatives.

2,34

Make sure that documentation

of ongoing reviews is kept on file and consult

with academic affairs, enrollment management,

legal counsel, and student services as part of a

collaborative process.

Ensure that the definition of diversity as it relates to

pipeline programs is inclusive and represents more

than race and ethnicity.

2

In stating objectives and institutional mission, tie

the goal of the educational benefits of diversity to

measurable strategies that promote access and equal

opportunity.

2

Consider adopting precise goals of racial literacy,

multicultural literacy, and cultural competence that

can be measured and monitored in connection with

the educational benefits of diversity.

63

In conducting regular reviews of diversity-related

programs and policies, incorporate specific

institutional evidence and outside sources that

support the connection between the university

mission and the educational benefits of a diverse

student body.

35

GUIDELINES FOR ANTIAFFIRMATIVE

ACTION BALLOT INITIATIVE STATES

In an effort to further diversity, the University of

Nebraska Board of Regents Ofce of the General Coun-

sel issued guidelines for its campuses to assist them in

complying with the I-424 ballot initiative in January

2009.

64

These guidelines serve as a resource in promot-

ing the compelling interest of diversity in higher edu-

cation within the legal parameters allowable by state and

federal law. The University of Nebraska guidelines draw

upon the experience and guidelines published by the

University of California in their efforts to ensure diver-

sity and comply with the Prop-209 ballot intiative.

65

Both the University of Nebraska and University of

California guidelines state that outreach programs tar-

geted exclusively for 1 gender, race, or ethnicity are not

allowed. However, as part of their comprehensive out-

reach programs, universities may sponsor programs that,

because of their content, are of particular interest to

members of a particular racial groups or 1 gender, if

they are open to all persons.

64,65

The University of

Nebraska guidelines use a conference on womens

issues in higher education that may attract more women,

as an example.

64

Furthermore, the University of California Regents

guidelines state:

Outreach. Proposition 209 prohibits outreach

programs that are targeted exclusively to or avail-

able exclusively for one gender or one or more

particular racial group, when such efforts pro-

vide informational or other advantages to can-

didates who have access to them. Nevertheless,

the University may, as part of a comprehensive

program of outreach, target or increase specific

efforts within that program to reach particular

groups where the programs benefits are available

broadly to other groups, and the special efforts

are necessary to reach the targeted groups mem-

bers effectively and therefore to level the infor-

mational playing field. Such activities might

include, for example, workshops or materials ori-

ented toward specific communities or groups. The

benefits of the program must be available on a

non-selective basis such that interested individu-

als from all racial groups and both genders have

access to the same benefits.

65

In terms of admissions criteria, the University of

Nebraska guidelines specically state:

Use of Neutral Selection Criteria. The Universi-

ty may choose to advance its educational goals,

including diversity, by considering gender/race/

ethnicity neutral selection criteria in both admis-

sions and employment decisions. Economic dis-

862 JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION VOL. 101, NO. 9, SEPTEMBER 2009

PIPELINE PROGRAMS AND RECENT LEGAL CHALLENGES

advantages, first generation college attenders,

neighborhood or community circumstances, low-

performing secondary schools, and the impact of

an applicants experiences are permissible crite-

ria, which may promote greater diversity. (Note:

the Universitys long tradition of admitting any

Nebraska undergraduate student who meets cam-

pus academic requirements generally eliminates

questions of preferential admission.)

64

The guidelines also allow campuses to continue tak-

ing steps to comply with their federal afrmative action

programs and plans. States with similar antiafrmative

action laws may wish to further consult the University of

California and University of Nebraska guidelines in

terms of assessing neutral selection criteria and review-

ing race- and gender-specic admissions, outreach, and

hiring programs.

64,65

CONCLUSION

While pipeline programs are designed to prepare dis-

advantaged students for health professions education,

starting as early as kindergarten, the dismantling of afr-

mative action has the potential to end these programs

and signicantly reduce the number of URM students

who enter the pipeline early and are prepared for careers

in the health professions. It is essential that the diverse

pipeline programs are preserved through creative

approaches designed to close opportunity gaps and

improve academic readiness.

To preserve these diversity pipeline programs in light

of continuous afrmative action challenges, there must

be a paradigm shift and a reframing of the issues sur-

rounding afrmative action. As Frank Wu, law professor

and former dean of the Wayne State University School

of Law, observed at a Michigan Journal of Race and

Law symposium in 2008, we must move from debate

to dialogue among individuals and communities and

ask a different question.

63

According to Wu, the question

should be, What will we do to make good on the ideals

we claim to sharewhat will we do as a diverse democ-

racy so that all of us are able to write the scripts of our

own lives?

63

As Wu points out, such questions force us to move

from a debate of the pros and cons of afrmative action

to the historical reasons and the contemporary dispari-

ties that make afrmative action still necessary.

63

They

implore us as a collective to tackle the difcult and lin-

gering inequalities in socioeconomic status, educational

nance reform, postsecondary access, and true admis-

sions indicators as predictors of actual degree comple-

tion. In doing so, we collaborate in our dialogue and

explore new and novel ways to improve enrichment pro-

grams that act as a bridge for URM students in the health

profession.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks to Mary Jo Price Esq, Carmen Maurer

Esq, and Lois Colburn for their feedback and comments

related to this manuscript. Thanks also to Teresa Hart-

man, K. Diane Ullrich, Carly R. Crim, Margaret T. Rob-

inson, Dr Mary McNamee, Stacie Ortmeier, Anne Con-

stantino, and Jo Giles Galbreath for their assistance with

the preparation of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

1. Katznelson I. When affirmative action was white: an untold history of

racial inequality in twentieth-century America. 1st ed. New York: W.W. Nor-

ton; 2005.

2. Coleman AL, Palmer Scott R. From theory to action: policy development

stategies for meeting access and diversity goals in lawful ways. The Col-

lege Boards collaborative on access & diversity in higher education. Den-

ver, CO: The College Board; May 2008.

3. Schmidt P. 5 more states may curtail affirmative action. Chron High Educ.

October 19, 2007.

4. Wiedeman R. Voters in 13 states will cast ballots in referenda related to

higher education. Chron High Educ. October 10, 2008. http://chronicle.

com/weekly/v55/i07/07a02201.htm. Accessed October 31, 2008.

5. Fulbright L. Connerly gearing up for wider crusade: affirmative action foe

considers launching campaigns in 9 states. The San Francisco Chronicle.

December 14, 2006. http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=c/

a/2006/12/14/MNGR2MV3I51.DTL. Accessed October 31, 2008.

6. Wiedeman R. Analysis: how Colorado became the first state to reject a

ban on affirmative action. Chron High Educ. November 10, 2008. http://

chronicle.com/daily/2008/11/7031n.htm. Accessed November 11, 2008.

7. Wiedeman R. Ban on preferences Succeeds in Nebraska; Colorado

measure remains undecided. Chron of High Educ. November 5, 2008.

http://chronicle.com/free/2008/11/6652n.htm. Accessed November 5,

2008.

8. Hansen M. City, NU to look for legal ways to aid minorities. The Omaha

World-Herald. November 6, 2008. http://www.omaha.com/index.php?u_

page=2835&u_sid=10479833. Accessed November 6, 2008.

9. The US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Federal laws pro-

hibiting job discrimination questions and answers. 2002. http://www.eeoc.

gov/facts/qanda.html. Accessed March 13, 2009.

10. Welch S, Gruhl J. Affirmative action and minority enrollments in medical

and law schools. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press; 2001.

11. US Commission on Civil Rights, The commission, affirmative action, and

current challenges facing equal opportunity in education. 2003. http://

www.usccr.gov/aaction/ccraa.htm. Accessed October 31, 2008.

12. Executive Order 8802, 3 C.F.R. 234 (1941).

13. Executive Order 11246, 3 C.F.R. 339 (1965).

14. Executive Order 11375, 3 C.F.R. 684 (1967).

15. Executive Order 11478, 34 Fed. Reg. 12985 (1969).

16. Executive Order 12106, 44 Fed. Reg. 1053 (1978).

17. Executive Order 13087, 42 USC 2000e (2000).

18. Belton R., Labor Law Group (US). Employment discrimination law : cases

and materials on equality in the workplace. 7th ed. Eagen, MN: Thomson/

West; 2004.

19. Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. 42 USC 2000e et seq.

20. USCA. Const. Amend. 14.

21. Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 USC 2000d et seq.

22. Fact Sheet: Your rights under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. June

9, 2008. http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/civilrights/resources/factsheets/yourright-

sundertitleviofthecivilrightsact.pdf. Accessed October 30, 2008.

23. Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, 20 USC 1681 et. seq

24. Nickens HW, Smedley BD, Institute of Medicine (US). The right thing to

do, the smart thing to do: enhancing diversity in the health professions:

summary of the Symposium on Diversity in Health Professions in honor of

Herbert W. Nickens, M.D. Washington, DC: National Academy Press: Insti-

JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION VOL. 101, NO. 9, SEPTEMBER 2009 863

PIPELINE PROGRAMS AND RECENT LEGAL CHALLENGES

tute of Medicine; 2001.

25. Smedley BD, Butler AS, Bristow LR, et al. In the nations compelling

interest: ensuring diversity in the health-care workforce. Washington, DC:

National Academies Press; 2004.

26. Coleman AL, Palmer SR. Diversity in higher education: a strategic plan-

ning and policy manual regarding federal law in admissions, financial aid,

and outreach. 2nd ed. New York: College Board; 2004.

27. Alexander L, Schwarzschild M. Grutter or otherwise: racial preferences

and higher education. Const Comment. 2004;21.

28. Herrnstein R, Murray C. The bell curve: intelligence and class structure in

American life. New York: Simon and Schuster; 1994.

29. Jencks C, Meredith P, eds. The black-white test gap. Washington DC:

Brookings Institute; 1998.

30. Brown v. Board of EducationTopeka, Kansas, 347 US 482 (1954).

31. Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 483 US 265 (1978).

32. Perry BA. The Michigan affirmative action cases. Lawrence, KS: Univer-

sity Press of Kansas; 2007.

33. Coleman AL, Palmer SR. Admissions and diversity after Michigan: the

next generation of legal and policy issues. Washington, DC: The College

Board; 2006.

34. Malcom SM, Chubin DE, Jesse JK. Standing our ground: a guidebook

for STEM educators in the post-Michigan era. Washington, DC: American

Association for the Advancement of Science; October 2004.

35. Coleman AL, Palmer SR., Winnick, SY. Roadmap to diversity: key legal

and educational policy foundations for medical schools. Washington, DC:

Association of American Medical Colleges; 2008.

36. US Commission on Civil Rights. Toward an understanding of percent-

age plans in higher education: are they effective substitutes for affirmative

action. 2000. http://www.usccr.gov/pubs/percent/main.htm. Accessed

October 31, 2008.

37. American Council on Education. Affirmative action in higher education

after Grutter v. Bollinger and Gratz v. Bollinger. 2003. http://www.acenet.

edu/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Search§ion=Legal_Issues_and_

Policy_Briefs1&template=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentFileID=716.

Accessed 11/10/08.

38. Smith v. University of Washington Law School, 233 F.3d 1188 (9th Cir.

2000).

39. Hopwood v. Texas, 78 F. 3d 932 (5th Cir. 1996).

40. Gratz et al v. Bollinger et al, 539 US 244 (2003).

41. Grutter v. Bollinger et al, 539 US 306 (2003).

42. Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1 et

al., 127 S.Ct. 2738 (2007).

43. Meredith v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 127 S.Ct. 2738 (2007).

44. Coleman AL, Palmer SR., Winnick, SY. Echoes of Bakke: A fractured

Supreme Court invalidates two-race conscious k-12 student assignment

plans but affirms the compelling interest in the educational benefits of

diversity. Washington, DC: The College Board; July 2007.

45. Coleman AL, Palmer SR., Winnick, SY. Race-neutral policies in higher

education: from theory to action. Washington, DC: The College Board;

June 2008.

46. Przypyszny J, Tromble, K. Impact of Parents Involved in Community

Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1 and Meredith v. Jefferson County

Board of Education on Affirmative Action in Higher Education. 2007. http://

www.acenet.edu/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Legal_Issues_and_Policy_B

riefs2&CONTENTID=23636&TEMPLATE=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm. Accessed

November 11, 2008.

47. Office of Civil Rights. Achieving diversity: race-neutral alternatives in

American education. Washington DC: Department of Education; March

2004. http://www.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/edlite-raceneutralreport2.

html. Accessed March 16, 2009.

48. Farmer J. The No Child Left Behind Act: will it produce a new breed of

school financing litigation. Colum J Law Soc Probl. 2005;38:443.

49. Calleros CR. Law, policy, and strategies for affirmative action admis-

sions in higher education. In Selected Essays from the Western Law Profes-

sors of Color conference 2006. Calif West Law Rev. 2006;23.

50. Curtis JL. Affirmative action in medicine: improving health care for

everyone. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press; 2003.

51. Coleman AL, Palmer SR., Sanghavi, E, Winnick, SY. From federal law to

state voter intiatives: preserving higher educations authority to achieve

educational, economic, civic, and security benefits associated with a

diverse student body. Washington, DC; 2007. http://www.collegeboard.

com/prod_downloads/diversitycollaborative/preserving-higher-educa-

tion-authority.pdf. Accessed November 4, 2008.

52. Schmidt P. 3 States poised to vote on affirmative action. Chron High

Educ. July 18, 2008. http://chronicle.com/weekly/v54/i45/45a01702.htm.

Accessed October 31, 2008.

53. Cohen J. The consequences of premature abandonment of affirmative

action in medical school admissions. JAMA. 2003.

54. Steinecke A, Terrell, C. After affirmative action: diversity at California

medical schools. Analysis: In Brief. September 2008;8(6). http://www.aamc.

org/data/aib/aibissues/aibvol8_no6.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2008.

55. Baker M. Outreach offsets I-200 decline. The U.W. Daily. December

9, 2004. http://dailyuw.com/2004/12/9/outreach-offsets-i-200-decline/.

Accessed October 31, 2008.

56. Marin P, Lee, EK. Appearance and reality in the sunshine state: the Tal-

ented 20 Program in Florida. Cambridge, MA: The Civil Rights Project at

Harvard University; 2003: http://www.civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/

affirmativeaction/florida.pdf. Accessed November 12, 2008.

57. Yardley W. One Florida rules hit campuses. St. Petersburg Times. Febru-

ary 23, 2000. http://www.sptimes.com/News/022300/State/One_Florida_

rules_hit.shtml. Accessed November 1, 2008.

58. Horn CL, Flores, SM. Percent plans in college admissions: a compara-

tive analysis of three states experiences. Cambridge, MA; 2003: http://

www.civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/affirmativeaction/tristate.pdf.

Accessed November 12, 2008.

59. US Commission on Civil Rights. Beyond percentage plans: the chal-

lenge of equal opportunity in higher education. Washington, DC: US Com-

mission on Civil Rights - Office of Civil Rights Evaluation; November 2002:

http://permanent.access.gpo.gov/www.usccr.gov/pubs/percent2/main.

htm. Accessed November 11, 2008.

60. Geiser S, Ferri C, Kowarsky J. Admissions briefing paper - underrepre-

sented minority admissions at UC after SP-1 and Proposition 209: trends,

issues, and options. 2000. http://www.ucop.edu/sas/researchandplan-

ning/admbriefpaper.pdf. Accessed November 14, 2008.

61. Chacon J. Race as a diagnostic tool: Latinas/os and higher education

in California post-209. Paper presented at: Symposium: Taking Initiative on

Initiatives: Examining Proposition 209 and Beyond, 2008; Berkeley, CA. In

Calif Law Rev. 2008;96:1215.

62. Keller J, Hoover E. University of California adopts sweeping changes in

admissions policy. Chron High Educ. February 13, 2009. http://chronicle.

com/weekly/v55/i23/23a.03301.htm. Accessed March 19, 2009.

63. From Proposition 209 To Proposal 2: Examining the effects of anti-affir-

mative action voter initiatives. Paper presented at: Michigan Journal of

Race and Law Symposium, February 9, 2008; University of Michigan Law

School, Ann Arbor, MI. In Mich J Race Law. 2008;13:461.

64. Milliken, JB. Board of Regents Resolution and General Counsels Guid-

ance on Enhancing Diversity Following Amendment of the State Constitu-

tion, January 29, 2009: Lincoln, NE. http://www.nebraska.edu/docs/legal/

GCGuidanceArt1Sec30.pdf. Accessed March 3, 2009.

65. Regents of the University of California Office of the General Counsel.

Enhancing Diversity at the University of California. http://www.ucop.edu/

ogc/enhance_diversity.html. Accessed March 13, 2009. n

Вам также может понравиться

- Ongoing Pediatric Health Care For The Child Who Has Been MaltreatedДокумент18 страницOngoing Pediatric Health Care For The Child Who Has Been MaltreatedJesse M. MassieОценок пока нет

- Effective Discipline To Raise Healthy Children: Policy StatementДокумент12 страницEffective Discipline To Raise Healthy Children: Policy StatementJesse M. MassieОценок пока нет

- IJMEДокумент7 страницIJMEJesse M. MassieОценок пока нет

- Oral and Dental Aspects of Child Abuse and Neglect: Clinical ReportДокумент10 страницOral and Dental Aspects of Child Abuse and Neglect: Clinical ReportJesse M. MassieОценок пока нет

- What Is Child Abuse and Neglect? Recognizing The Signs and SymptomsДокумент8 страницWhat Is Child Abuse and Neglect? Recognizing The Signs and SymptomsJesse M. MassieОценок пока нет

- Status EpileticusДокумент2 страницыStatus EpileticusJesse M. MassieОценок пока нет

- dBA PROTECT YOUR HEARINGДокумент4 страницыdBA PROTECT YOUR HEARINGJesse M. MassieОценок пока нет

- Making The Most of Mentors: A Guide For MenteesДокумент5 страницMaking The Most of Mentors: A Guide For MenteesJesse M. MassieОценок пока нет

- Suidi Oklahoma ProviderДокумент28 страницSuidi Oklahoma ProviderJesse M. MassieОценок пока нет

- Identifying Child Abuse Fatalities During Infancy: Clinical ReportДокумент11 страницIdentifying Child Abuse Fatalities During Infancy: Clinical ReportJesse M. MassieОценок пока нет

- i-PASS OBSERVATION TOOLДокумент1 страницаi-PASS OBSERVATION TOOLJesse M. MassieОценок пока нет

- Cbig Cross-ReportingДокумент25 страницCbig Cross-ReportingJesse M. MassieОценок пока нет

- Jpeds Aom 208Документ3 страницыJpeds Aom 208Jesse M. MassieОценок пока нет

- COVID Positive/PUI: PAPR Prioritization MatrixДокумент1 страницаCOVID Positive/PUI: PAPR Prioritization MatrixJesse M. MassieОценок пока нет

- Minority YouthДокумент28 страницMinority YouthJesse M. MassieОценок пока нет

- Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences (Aces) :: Leveraging The Best Available EvidenceДокумент40 страницPreventing Adverse Childhood Experiences (Aces) :: Leveraging The Best Available EvidenceJesse M. MassieОценок пока нет

- Intimate Partner Violence, Sexual Violence, Stalking: Before The Age of 18Документ1 страницаIntimate Partner Violence, Sexual Violence, Stalking: Before The Age of 18Jesse M. MassieОценок пока нет

- Fireworks ShowДокумент2 страницыFireworks ShowJesse M. MassieОценок пока нет

- Male Victims of Intimate Partner Violence: Did You Know?Документ3 страницыMale Victims of Intimate Partner Violence: Did You Know?Jesse M. MassieОценок пока нет

- Domestic Violence Oklahoma 2017Документ44 страницыDomestic Violence Oklahoma 2017Jesse M. MassieОценок пока нет

- Noisey PlanetДокумент1 страницаNoisey PlanetJesse M. MassieОценок пока нет

- Kinshipguardianship PDFДокумент139 страницKinshipguardianship PDFJesse M. MassieОценок пока нет

- How Loud Is Too LoudДокумент2 страницыHow Loud Is Too LoudJesse M. MassieОценок пока нет

- Advancing Health Equity: A Practitioner'S Guide ForДокумент132 страницыAdvancing Health Equity: A Practitioner'S Guide ForJesse M. MassieОценок пока нет

- How Does Noise Damage Your Hearing?Документ2 страницыHow Does Noise Damage Your Hearing?Jesse M. MassieОценок пока нет

- Cbig Child Abuse and Neglect Fatalities 2017Документ8 страницCbig Child Abuse and Neglect Fatalities 2017Jesse M. MassieОценок пока нет

- In Drinking Water: Sources of LEADДокумент1 страницаIn Drinking Water: Sources of LEADJesse M. MassieОценок пока нет

- CDC Capacity BuildingДокумент16 страницCDC Capacity BuildingJesse M. MassieОценок пока нет

- Aap Food Insecurity Toolkit For ProvidersДокумент39 страницAap Food Insecurity Toolkit For ProvidersJesse M. MassieОценок пока нет

- Essentials For Childhood:: Steps To Create Safe, Stable, Nurturing Relationships and EnvironmentsДокумент1 страницаEssentials For Childhood:: Steps To Create Safe, Stable, Nurturing Relationships and EnvironmentsJesse M. MassieОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5795)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1091)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Paper LSM 2Документ2 страницыPaper LSM 2Abdul Rahman ZAHOORОценок пока нет

- 06 Galman v. Sandiganbayan (De Mesa, A.)Документ3 страницы06 Galman v. Sandiganbayan (De Mesa, A.)Ton RiveraОценок пока нет

- Nyaung Yan PeriodДокумент9 страницNyaung Yan Periodaungmyowin.aronОценок пока нет

- Navy All Hands 201001Документ52 страницыNavy All Hands 201001adereje7Оценок пока нет

- No - Match N: Voter DocumentsДокумент2 страницыNo - Match N: Voter DocumentsMD Bayezid Ahasaan Shaheen100% (1)

- Defensor-Santiago vs. SandiganbayanДокумент2 страницыDefensor-Santiago vs. SandiganbayanKayelyn LatОценок пока нет

- Consti2Digest - PN-012 Tolentino Vs Secretary, 235 SCRA 632 (1994)Документ2 страницыConsti2Digest - PN-012 Tolentino Vs Secretary, 235 SCRA 632 (1994)Lu CasОценок пока нет

- Candidate Julio GuzmanДокумент10 страницCandidate Julio GuzmanwilsonОценок пока нет

- 02a - Rdg-1796 Treaty of TripoliДокумент4 страницы02a - Rdg-1796 Treaty of TripoliAnthony ValentinОценок пока нет

- SPG NarrativeДокумент1 страницаSPG NarrativeLota Lagahit96% (26)

- HB2482Документ3 страницыHB2482Sinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneОценок пока нет

- MR Arif Khan Sahaab 1Документ2 страницыMR Arif Khan Sahaab 1Muhammad Arif KhanОценок пока нет

- DodatakДокумент122 страницыDodatakmilos_vuckovic_4Оценок пока нет

- China Southern African and Extractive IndustriesДокумент250 страницChina Southern African and Extractive IndustriesChola MukangaОценок пока нет

- March Edition - She Glorifying Businesses - The Global HuesДокумент69 страницMarch Edition - She Glorifying Businesses - The Global HuestheglobalhueОценок пока нет

- Administrative Law Course OutlineДокумент21 страницаAdministrative Law Course Outlineidko2wОценок пока нет

- Culture and Customs of The Sioux Indians (2011) BBS PDFДокумент215 страницCulture and Customs of The Sioux Indians (2011) BBS PDFGeorge Kwamina AnamanОценок пока нет

- Samvidhaan Episode 3 Documentary ReviewДокумент3 страницыSamvidhaan Episode 3 Documentary Reviewdildhar80% (10)

- 3) Municipality of Sogod vs. Hon. RosalДокумент3 страницы3) Municipality of Sogod vs. Hon. RosalBreth1979Оценок пока нет

- SBGR SampleДокумент54 страницыSBGR SampleGeen Abrasado0% (1)