Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

HetersoxualMasculinity PDF

Загружено:

Marina FrançaИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

HetersoxualMasculinity PDF

Загружено:

Marina FrançaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Hegemonic

Heterosexual

Masculinity

BLYE FRANK

S

ome of us who think about issues of gender and sex-

uality know that they are not simply individual issues,

but rather are fundamental social processes affecting

every member of society. Gender and sexuality are not sepa-

rated from other aspects of our lives.

Millionsof women knowthat their sexlivesarelimitedor dictated

by financial dependence upon men. Millionsof women have ex-

perienced the inadequacy of abortion facilitiesand knowthat this

is the result of political choices. Millionsof young people know

that their sexualityhas been restricted bylivingwiththeir parents.

And many people knowthat their sex liveshave invulved power

-

StudiesinPoliticalEconomy 24,Autumn 1987

159

Studies in Political Economy

relationships and that these power relationships are in some way

wrong and unnecessary. The link between sex and politics, the way

in which sex is political, is not just a concern of left political

activists; it is already an important question of the majority.'

These issues need investigation, analysis, and theorization.

They must be moved from the often conceptualized base of

individuality where they are marginalized or "evaluated", to

the political economic arena where they can be connected to

other political struggles within a framework of political econ-

omy. Within a political economy framework, gender and sex-

uality will be moved outside of the "official" ideology of gender

roles and relocated in the material and social conditions of

their existence.

Political economy, with its quite recent "discovery" of gen-

der, and its almost total omission of sexuality, is still seriously

flawed. A male stream political economy, which continues to

maintain a sexism that marginalizes women and renders sex-

uality invisible, does not live up to its claim to a study of

society as an integrated whole. For example, Heather J on

Maroney and Meg Luxton comment with reference to women

on the deficit theorizing found even in recent work in political

economy.

As for the rising sons (and occasionally daughters) of the political

economy revival, while they realized that "women" exist as asocial

category and political force, and supported on principle work on

"women", they have not yet for the most part, incorporated this

understanding into their work. While they increasingly include a

discussion of women, they have yet to move beyond the stage of

"adding women" to make a genuine attempt to theorize gender ...

the new generation of thinkers associated with the new Canadian

political economy revival, has followed all too closely in the foot-

steps of the founding fathers.s

If political economy is to begin to expand theoretically to

provide an analysis of society as a whole, then it must not only

continue to shift its theoretical advances to include gender; it

must also include sexuality and, in particular, heterosexuality

and masculinity. Heterosexuality and masculinity are not neu-

tral nor are they biological. They are social accomplishments

of a political nature located within a larger set of political,

160

Frank/Masculinity

economic, and social relations. Gender obedience to hetero-

sexuality and masculinityisahuman activity,asocial product

embodied by individual men intheir everyday, routine set of

social relations. As acollectiveprocess, gender obedience by

men expresses themes of competition with other men, the

exploitation and subordination of women and other men,

violence toward women and other men, and homophobia.

Hegemonicheterosexual masculinityissociallyconstructed and

sociallyimposed. Becauseitcanbesociallyresisted, thereexists

thepossibilityof change.

In the context of this argument, this review focuses on

fragments of the existing literature on gender and sexuality,

and argues for the recognition of the social constitution of

hegemonic heterosexual masculinity and its location in the

larger set of social relations as a problematic for socialist

thought and practice. In this sense, it is a radical reviewof

radical lacunae in the literature, whichuses these fragments

toconstruct anargument against hegemonicheterosexual mas-

culinity. If weaccept this problematic as connected to other

social processes of oppression suchas militarism, racismand

sexism, then this work has an agenda of major change. Insti-

tutionalized forms of racism, militarism, sexismandheterosex-

ismare sociallyregulated acts of violence. Men's violenceis

often symbolizedand embodied inthe individual man. How-

ever, it is important to emphasize that patriarchal structures

of heterosexist masculine authority, domination and control

arediffused throughout societyinitssocial,political,economic

and ideological activities.

This essayreviewsan approach that grounds heterosexual

masculinity in the social practices of institutions and their

agents whereagender regimeisimposed, encouraging partic-

ular forms of masculinity whilediscouraging others. Political

economy seldomhas taken seriouslythequestion of just how

it isthat heterosexuality and masculinityareconnected to the

production and maintenance of the present systemof power.

The literature of the men's movement seldomhas taken seri-

ouslythedifferences inpower betweenmen. It hastended to

produce an image of men that is white, middle class and

heterosexual. As Ned Lyttleton has pointed out: "ananalysis

of masculinity that does not deal with the contradictions of

power imbalances that exist between men themselves will be

161

Studies in Political Economy

limited and biased, and itslimitsand biaseswill beconcealed

under the blanket of shared male privilege." Gary Kinsman

suggests that "a series of masculinities becomes sublimated

under one formof masculinity that becomes'masculinity'. As

aresult, sociallyorganized power relationsamongandbetween

men based on sexuality, race, class, or age have been ne-

glected."4Political economists and the men's movement have

not explored thewaysinwhichheterosexuality andmasculinity

are connected to work, leisure, our everyday social relations,

and our most intimateexperiences and communication. Carol

Vance's reviewof the literature on female sexuality can still

statethat for mostanalystsandother people: "sexual behaviour

is seen as an isolated private event, not connected to the

distribution of resources and power, the gender system, the

organization of production, or raceand class","

The political economyof hegemonic heterosexual masculin-

ity isan approach containing avision: avisionthat aqualita-

tively better society is possible without the restrictive and

oppressive gender and sexuality that issooften enforced by

our social institutions, aswell asbyeveryday social terrorism.

The vision, then, should not be merely to change people's

consciousness in regard to masculinity and the sex/gender

system, or simply to reconstruct institutions along different

ideologies and practices. Rather, at the core of the visionis

the aim of changing a set of historically structured power

relations-a changeinthesocial,political, andeconomicstruc-

tures that constitutetheground of domination andoppression

insomany ways. Gery Kinsmancomments onthenecessityof

changing hegemonic heterosexuality masculinity.

This redefining of masculinityand sexualitywill alsohelp destroy

the anxieties and insecurities of many straight men who try so

hard to be 'real' men. But the successof this understanding de-

pends ontheabilitytodevelopalternativevisionsand experiences

that will help all people understand how their lives could be

organized without heterosexuality as the institutionalized social

norm. Suchagoal isaradical transformation of societyin which

everyone will be able to gain control over his or her own body,

desires, and life.e

Bert Youngsuggests IIIhis introduction to Who's On ToP?

The Politics of Heterosexuality, that the political dimensions of

162

Frank/Masculinity

sexualityareoften completelyignored, "includingthedivision

of labour along gender linesand asocial classsystemthat is

predominately capitalist and patriarchal. Mendo have more

freedomtoexpress their sexualitythanwomenandheterosex-

ualshavemorefreedomthangays; theseprivilegesdoprovide

apower base, interms of social control,"? Heterosexual privi-

legeisoftennot understood. Lesbian-feminist,CharlotteBunch,

once explained to heterosexual women that the best wayto

findout what heterosexual privilegeisall about istogoabout

for afewdaysasalesbian.

What makesheterosexuality workisheterosexual privilege-and if

youdon't haveasenseof what heterosexual privilegeis, I suggest

that you go home and announce to everyone that you know-a

roommate, your family,thepeopleyouworkwith, everywherethat

yougo-that you're aqueer. Trybeingaqueer for aweek.s

Thesilencearound heterosexismandheterosexual privilege

must be broken. Feminismhas begun to explore sexuality

beyond simple theories of repression to showhow gender/

sexualityare relations of power in amale-dominated society.

This, of course, allowsus to see that issuesof gender and

sexualityarechangeableandanintergral part of personal and

social struggle. The human activitythat produces sexrelations

as categorical and hierachical can be calledinto question in

the making of a new social terrain around sexuality and

gender. GayleRubin callsthis the "Charmed Circle" of sex-

uality, which has heterosexual procreative masculinityat the

topof thepyramid.

Modern Western societiesappraise sexactsaccording to ahierar-

chial systemof sexual value. Marital, reproductive heterosexuals

are alone at the top of the erotic pyramid. .. Individuals whose

behavior stands high inthis hierarchy arerewarded withcertified

mental health, respectability, legality, social and physical mobility,

institutional support, and material benefits. Assexual behavior or

occupations fall lower on the scale, the individuals who practice

themare subjectedto apresumption of mental illness, disrespect-

ability, criminality, restricted physical and social mobility, loss of

institutional support, and economicsanctions."

Theselivedpatterns of hegemonicheterosexual masculinity

are patterns of power, and are a significant underpining uf

163

Studies in Political Economy

patriarchal culture. Yettheserelations of power havereceived

marginal, rather than central treatment.

In our society heterosexuality as an institutionalized norm has

becomeanimportant means of social regulation, enforced bylaws,

police practices, family and social policies, school. and the mass

media. In its historical development, heterosexuality is tied with

theinstitution of masculinity,whichgivessocial and cultural mean-

ing to biological male anatomy, associating it with masculinity,

agressiveness, and an "active" sexuality.!?

Michael Kaufman suggests that:

radical socioeconomicand political changeisarequirement for the

end of men's violence... the process of achievingtheselong-term

goals contains many elements of economic, social, political, and

psychological change, eachof whichrequires afundamental trans-

formation of society.Suchtransformation will not becreated byan

amalgam of changed individuals; but there isarelationship be-

tween personal change and our abilitytoconstruct organizational,

political and economic alternatives that will be able to mount a

successful change to the status quo.II

Varda Burstyn moves issues of gender and sexuality into

the political and economic area of analysisin"Political Prece-

dents and Moral Crusades: Women, Sexand the State," citing

numerous connections between sex and the statesuchas: the

crosscountry travelsof theSpecial CommitteeonPornography

and Prostitution (the Fraser Committee); the firebombing of

Red Hot Video, a Vancouver porn outlet; the censoring of

progressive artists' work in Toronto and Vancouver; the trial

of Doctors Henry Morgentaler, Leslie Smoling and Robert

Scott, physicians at a Toronto abortion clinic, for conspiring

toprocure anabortion; theinjunction against Vancouver pros-

titutes forbidding themtoworkintheWestEndof Vancouver;

the mass arrests of gay men in Montreal bars and baths; the

extraordinary entrapment of gaymen inOrillia, Ontario; the

Alberta government's attempt toeliminate sexeducation; and

the list goes on.

12

It is, partially, the "seeing" of gender and

sexuality as individual and separate that has allowedthe gen-

der and sexual oppression of somany to continue within the

social, political, and economic structure that constitutes the

sourceof domination insomany ways.

164

Frank/Masculinity

Ian Lumsden, in "Sexuality and the State: The Politics of

'Normal' Sexuality," says:

The major institutions that affect collectivesexual behaviour inour

societyare subordinate to the interests of the dominant economic

class, which in turn is largely comprised of men imbued with

heterosexual and patriarchal values. The institutions that I havein

mind include the large corporations, which control not only the

content of advertising and hence of consumption, as well as the

mass media, which depend upon advertising revenue, and the

entertainment industry. Schools, universities, and most non-profit

foundations also fit into this category. These institutions promote

and disseminate economic and political beliefsconsistent withthe

interests of the dominant economicclass. Moreover, they alsofur-

ther the heterosexist values, which legitimizethe prerogatives of

heterosexual males, encourage the sexual and emotional depend-

enceof women upon men, and invalidatehomosexuality. For nei-

ther radical feminists nor openly gay men are to befound at the

pinnacle of power inour society.In addition to theseinstitutions,

which support the hegemony of heterosexual patriarchal values,

there arestateagenciesthat arespecificallyempowered tointervene

and regulate our sexual lives, suchaslawcourts, the policeforce,

censor boards and welfareagencies.

l3

Hegemonic heterosexual masculinity, then, is "hooked" to more

than sexual satisfaction in a society where male dominance is

part of a rigidly structured hierarchy. Certainly by now, with

the strength of the feminist movement, masculinity can no

longer be assumed to be socially and historically unproble-

matic. The hegemonic pattern is dominant; however, because

it is socially sustained, it can be resisted. This change will not

be brought about by boys playing with dolls or by women

having access tojobs that are traditionally men's employment.

Centuries-old patriarchal orders are not easily eradicated.

Domination by men of other men and women is based on,

and perpetuated by, a wide range of social structures, from

our intimate sexual relationships to the organization of eco-

nomic and political life.i-

Dorothy Smith suggests that the resurgence of the women's

movement of the 1960s began to raise questions about the

extent of men's control of the ideological apparatus of the

state; and especially those processes highly controlled by men

to produce and distribute knowledge-images, ideas, symbols,

language, information, etc.-through which women and men

165

Studies in Political Economy

cometo understand themselves, eachother, and the worldin

which they live.

15

The approach that wetake to this analysis

of theabsenceof research onmen's influence, and specifically

on masculinity, needs to bearather unusual one. Manysocial

scientists, including those on the left, have not often given

much timeor thought to the influenceof the "maleperspec-

tive" and its neglect in research and analysis. This lack of

investigation isbecause of the enormous influence of hege-

monic masculinityonevery person whohaslivedinapatriar-

chal culture. Whiledeeply immersed in "maleness", wehave

developed styles of thought, knowledge, and waysof doing

centred around the values, concerns, and emphasis of hege-

monic heterosexual masculinity. Masculinity, according to

Madeline Arnot in her work on the political economy of

gender relations, needs to beseennot simplyaswhat it isto

the male (asidentity), but rather asactivity(asaset of social

relations) aswhat malesdo, aspractice.is

Oppression, exploitation, power and social control offer a

more powerful account of the constraints that operate in

personality and insocial organization, andof thewayinwhich

the twolevelsare linked in the process of being reproduced.

VardaBurstynargues: "masculinedominanceisnot something

that can be neatly removed, like a decrepit porch off an

otherwisestrong house. It ismoreliketheframeof abuilding,

shaping family life, the paid workforce, political institutions,

education, art and science. Women and men working for

equality are in effect asking for changes throughout every

level of society."l7

Most males consciously or unconsciously consent to this

dominant version of masculinity. Most males can be seen to

undergo a process of transforming various meanings and

messagesto produce aconstellationof behavior, whichwecan

call hegemonic heterosexual masculinity.Menbecometheem-

bodiment of that sociallycreated classification.They external-

ize this masculinity through their speech, their dress, their

physical appearance and presence, and their relations with

others.

What istheconnection to thelarger set of social relations?

Vance says that "'scientific' knowledge suggesting that the

dominant cultural arrangements are the result of biology-

166

Frank/Masculinity

and, therefore, intrinsic, external, and unchanging-are usu-

ally ideologies supporting prevailing power relations. Deeply

felt personal identities-for example masculinity/feminityor

heterosexual/homosexual-are not privateor solelythe prod-

uct of biology, but are created through the intersection of

political, social, and economicforces, whichvaryover time.is

It is the relations within institutions assistingin the main-

tenance of heterosexual masculinitythat need to be situated

within the larger nexus of relations, of which they are a

constitutive part. The knowledge that is produced and the

social relations that dominate theseinstitutions act asamech-

anismof cultural and economicpreservation and distribution.

These things need to be looked at with specificattention to

masculinity, and to the way in which they help maintain a

"gender regime" which benefits those in power. Marianna

Valverdesuggeststhat:

Sexuality is not something we'have', our personal property that

wemight choose to 'share' with others, but rather isa process in

whichthe powers of thestate, of thescientificand moral establish-

ments, and the sexist ideology of maledefined pleasure, are con-

stantly meeting resistance from individuals and groups. The ex-

perience of individuals givethemastarting point tochallenge the

ideas and power of thosewhocreate oppression.t?

Hegemonic heterosexual masculinity, in this sense, should

be seen for what it is-a political issue-a form of social

control, a central organizing principle that supports present

power arrangements. Hegemonic heterosexual masculinity is

articulated at many points within the economic, social and

political structures of the material world. Hegemonic hetero-

sexual masculinity isan obstacleto atruly socialistsociety; it

supports thepresent systemof capitalism.

Unraveling howpresent-day relations hold hegemonic het-

erosexual masculinity in place, begins the process of under-

standing howthat dominant formof masculinityassistsinthe

production of anunjust andunequal societywheremalepower

hasbeen harnessed toworkfor political ends. The struggleto

dispossessheterosexual malesof their power whilereconstruct-

ingthemeaning of masculinitywill,indeed, bealengthy and

difficult task.

167

Studies in Political Economy

Placing the concept of hegemony, rather than that of re-

production, at the core of an analysis of sex/gender and

masculinity makes it easier to render visibletheactiveprocess

of "doing" gender and sexuality, theexistenceof power strug-

gles and points of conflict, and the range of alternatives that

do exist. Hegemony further allowsus to remember that the

power of the dominant interests is never total, nor entirely

secure. Hegemony is a weapon which must be continuously

struggled for, won, and maintained. In this analysisthen, we

can begin to seethat heterosexual hegemonic masculinity-as

well asother issuesaround gender and sexuality-is not simply

amatter of reproduction.

Tim Carrigan, Pat Connell, and J ohn Lee in, "Hard and

Heavy: Toward aNewSociologyof Masculinity;' suggest that:

this 'hegemony', then, alwaysrefers to ahistorical situation, aset

of circumstancesinwhichpower isheldandwon. Theconstruction

of hegemonyisnot amatter of pushingandpullingbetweenready-

formed groups, but is partly a matter of the formation of these

groupings. To understand the different kinds of masculinity,de-

mands aboveall, an examination of the practices inwhichhege-

mony is constituted and contested-in short, the political tech-

niques of the patriarchal social order. There isno easypath to a

major reconstruction of masculinity.w

The British historian J effrey Weekssays:

Nowwehave the opportunity to construct an alternative VISIOn

based on a realistic hope for the end of sexual domination and

subordination, for new sexual and social relations, for newand

genuineopportunities for pleasureandchoice.Wehavethechance

toregain control of our bodies, torecognizetheir potentialitiesto

the full, to take ourselves beyond the boundaries of sexualityas

weknowit. All weneed isthe political commitment, imagination,

and vision. The future, nowasever, isinour hands.

Contemporary theorists in political economy need to take

the essential step forward to include an analysis of the sex/

gender regimesothat afull understanding of thecomplexities

of societywill berendered visible.Then wecanbuildasociety

where everyday social relations are constructed so that all

human activityis given value, asocietyin whichthe material

conditions for freedom and equality are availabletoeveryone

168

Frank/Masculinity

on equal terms. Andrew Tolson states, "the challenge to so-

cialist men is to understand masculinity as a social problem

and thus to work together for anon-sexist socialistsociety."22

It is, then, not enough for malestreampolitical economists

to offer support to women's struggles. Wemust alsobuild a

theoretical base which speaks to men in particular. But the

very structure of hegemonic heterosexual masculinity stands

in the way. This structure needs to be addressed by male

political economistsandothers withinthecontext of apolitical

movement. And, asHoward Buchbinder, in"MaleHeterosex-

uality: The SocializedPenisRevisited" suggests: "itisclear that

the struggle must beboth personal and political, or it will be

neither. Aslongasthereisthepossibilityof acollectivestrategy

for men, it must be linked to our daily lives with women,

lovers, companions, friends, and comrades. Therein lies our

hope.

23

A political economy that claimsto study societyasan

integrated whole, without an investigationand analysisof he-

gemonic heterosexual masculinityand itsplaceinahierarchi-

cal gender/sexuality set of relations, isfailingtorespond toits

claim.

Notes

I would liketo thank my colleagueJ im Sacouman for his many helpful com-

ments during the writing of this reviewessay.

\. J amie Gough and Mike MacNair, Gay Liberation In the Eighties (London,

1985), p.3

2. Heather J on Maroney and Meg Luxton, "From Feminismand Political

Economy to Feminist Political Economy," in Feminism and Political Economy:

Women's Work. Women's Struggles (Toronto, 1987), pp. 9, II.

3. Ned Lyttleton, "Men's Liberation, MenAgainst Sexismand Major Dividing

Lines," Resources For Feminist Research 12:4 (December/J anuary 1983/84), p.

33.

4. Gary Kinsman, "Men Loving Men: The Challenge of Gay Liberation," in

Beyond Patriarchy: Essays By Men On Pleasure, Power, and Change, ed., Michael

Kaufman (Toronto, 1987), p. 104.

5. Carol Vance, "Pleasure and Danger: Toward a Politics of Sexuality," in

Pleasure and Danger: Exploring Female Sexuality (London, 1984), p.8.

6. Kinsman, "Men's Liberation," p. 116. (Seen. 4, above.)

7. Bert Young, Who's on ToP? The Politics of Heterosexuality, eds. Howard Buch-

binder et al. (Toronto, 1987), p.7.

8. Asquoted in Kinsman's article, p. 105. Kinsman goeson to suggest that the

same is true of "straight" men. That is. for heterosexual men to understand

the oppression and violence displayed toward men who do not produce

169

Studies in Political Economy

themselves as heterosexual men, "straight" men should tell people that they

are gay and, thus, seethe treatment they get. For further reading on this

notion of institutionalized heterosexuality, see Charlotte Bunch, "Not for

LesbiansOnly:' Ouest 11: 2(Fall 1975).AlsoseeAdrienne Rich, "Compulsory

Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence:' in Powers of Desire: The Politics of

Sexuality, eds., Snitow.Stansell and Thompson, (NewYork, 1983), pp. 127-

205.

9. Gayle Rubin, "Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politicsof

Sexuality:' inPleasure and Danger: Exploring Female Sexuality, ed., Carol Vance

(Boston, 1984), p. 278.

10. Kinsman, "Men's Liberation:' p. 104

II. Michael Kaufman, pp. 24, 25.

12. SeeWomen Against Censorship, (Toronto 1985), pp. 22, 23.

13. Unpublished article.

14. For a fuller discussion, see"Construction of Masculinityand The Triad of

Men'sViolence" inBeyond Patriarchy, ed., Michael Kaufman, (Toronto, 1987).

15. See"Women's Classand Family:' in D. Smithand V. Burstyn, Women, Class,

Family and State (Toronto, 1985) for amoreextensivediscussionof patriarchy

and classinthe capitalist mode of production.

16.See"School and the Reproduction of Classand Gender Relations" inSchool-

ing, Ideology and the Curriculum, eds., L. Barton et at. (Brighton, 1980).

17. Seethe"Introduction" in Women Against Censorship, (Toronto, 1985), p. I.

18. Vance, Pleasure and Danger, p.8(Seen.5above.)

19. Marianna Valverde, Sex, Power and Pleasure (Toronto, 1985), p. 17.

20. In Beyond Patriarchy p. 181. (Seen, 4, above.)

21.J effrey Weeks, Sexuality and Its Discontents (Boston, 1985), p. 260.

22. Andrew Tolson, The Limits of Masculinity (London, 1977), p. 146.

23. Buchbinder et ai, eds., Who's On TOP?, p. 82. (Seen. 7, above.)

170

Вам также может понравиться

- A Place of Sense: A Kinaesthetic Ethnography of Cyclists On Mont VentouxДокумент25 страницA Place of Sense: A Kinaesthetic Ethnography of Cyclists On Mont VentouxMarina FrançaОценок пока нет

- The Shaping of National AnthropologiesДокумент32 страницыThe Shaping of National AnthropologiesMarina FrançaОценок пока нет

- Social AnthropologyДокумент253 страницыSocial AnthropologyMarina FrançaОценок пока нет

- Prostitutes in History: From Parables of Pornography To Metaphors of ModernityДокумент25 страницProstitutes in History: From Parables of Pornography To Metaphors of ModernityMarina FrançaОценок пока нет

- Ollouz Loveanditscontents PDFДокумент15 страницOllouz Loveanditscontents PDFMarina FrançaОценок пока нет

- The Folk Society PDFДокумент17 страницThe Folk Society PDFRaon Borges100% (1)

- Porn and Sex Education, Porn As Sex EducationДокумент11 страницPorn and Sex Education, Porn As Sex EducationMarina FrançaОценок пока нет

- Total Immersion or Paddling?: Different Models of Fieldwork in Victorian (British) Anthropology, 1874 1914Документ8 страницTotal Immersion or Paddling?: Different Models of Fieldwork in Victorian (British) Anthropology, 1874 1914Marina FrançaОценок пока нет

- A Life Course Approach To Patterns and Trends in Modern Latin American Sexual BehaviorДокумент9 страницA Life Course Approach To Patterns and Trends in Modern Latin American Sexual BehaviorMarina FrançaОценок пока нет

- The Time of MoneyДокумент10 страницThe Time of MoneyMarina FrançaОценок пока нет

- Men Who Buy SexДокумент32 страницыMen Who Buy SexRed Fox100% (1)

- Addressing Health and Safety Concerns of Sex WorkersДокумент19 страницAddressing Health and Safety Concerns of Sex WorkersMarina FrançaОценок пока нет

- Crisis, Value, and Hope: Rethinking The Economy An Introduction To Supplement 9Документ13 страницCrisis, Value, and Hope: Rethinking The Economy An Introduction To Supplement 9Marina FrançaОценок пока нет

- GEORGE W. STOCKING Rousseau Redux or His PDFДокумент12 страницGEORGE W. STOCKING Rousseau Redux or His PDFMarina FrançaОценок пока нет

- BerdacheДокумент9 страницBerdacheMarina FrançaОценок пока нет

- Hugh-Jones Food For ThoughtДокумент17 страницHugh-Jones Food For ThoughtMarina FrançaОценок пока нет

- Moving Bodies, Acting SelvesДокумент33 страницыMoving Bodies, Acting SelvesMarina FrançaОценок пока нет

- Everyday Feminist Research Praxis: Doing Gender in The NetherlandsДокумент30 страницEveryday Feminist Research Praxis: Doing Gender in The NetherlandsMarina FrançaОценок пока нет

- Illouz LoДокумент15 страницIllouz LoKatarzyna SłobodaОценок пока нет

- IStengers PDFДокумент16 страницIStengers PDFMarina FrançaОценок пока нет

- Barthes, The Great Family of ManДокумент3 страницыBarthes, The Great Family of ManJorge de La BarreОценок пока нет

- Margaret Lock - Cultivating The BodyДокумент25 страницMargaret Lock - Cultivating The BodyLuiz DuarteОценок пока нет

- DREIER, Ole Subjectivity and Social PracticesДокумент141 страницаDREIER, Ole Subjectivity and Social PracticesMarina FrançaОценок пока нет

- Ingold 2001 Beyond Art and TechnologyДокумент15 страницIngold 2001 Beyond Art and TechnologyMauricio Del RealОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Holy Cross Academy Quarterly Cookery ExamДокумент4 страницыHoly Cross Academy Quarterly Cookery ExamAlle Eiram Padillo95% (21)

- Recombinant DNA TechnologyДокумент14 страницRecombinant DNA TechnologyAnshika SinghОценок пока нет

- Khatr Khola ISP District RatesДокумент56 страницKhatr Khola ISP District RatesCivil EngineeringОценок пока нет

- Customer Advisory For Fire Suppression Systems - V4 - ENДокумент18 страницCustomer Advisory For Fire Suppression Systems - V4 - ENsak100% (1)

- Kuan Yin 100 Divine Lots InterpretationДокумент30 страницKuan Yin 100 Divine Lots InterpretationEsperanza Theiss100% (2)

- HBSE-Mock ExamДокумент3 страницыHBSE-Mock ExamAnneОценок пока нет

- Bespoke Fabrication Systems for Unique Site SolutionsДокумент13 страницBespoke Fabrication Systems for Unique Site Solutionswish uОценок пока нет

- Batson Et All - 2007 - Anger and Unfairness - Is It Moral Outrage?Документ15 страницBatson Et All - 2007 - Anger and Unfairness - Is It Moral Outrage?Julia GonzalezОценок пока нет

- Jamec Air FittingsДокумент18 страницJamec Air Fittingsgoeez1Оценок пока нет

- Rachael-Lyn Anderson CHCPRT001 - Assessment 4 Report of Suspected Child AbuseДокумент3 страницыRachael-Lyn Anderson CHCPRT001 - Assessment 4 Report of Suspected Child AbuseAndrea AndersonОценок пока нет

- MSE 2103 - Lec 12 (7 Files Merged)Документ118 страницMSE 2103 - Lec 12 (7 Files Merged)md akibhossainОценок пока нет

- Sugar Reseach in AustraliaДокумент16 страницSugar Reseach in AustraliaJhonattanIsaacОценок пока нет

- Overhead Set (OBC)Документ19 страницOverhead Set (OBC)MohamedОценок пока нет

- SafewayДокумент70 страницSafewayhampshireiiiОценок пока нет

- Milovanovic 2017Документ47 страницMilovanovic 2017Ali AloОценок пока нет

- Multiple Sentences and Service of PenaltyДокумент5 страницMultiple Sentences and Service of PenaltyAngelОценок пока нет

- Hospital & Clinical Pharmacy Q&AДокумент22 страницыHospital & Clinical Pharmacy Q&AKrishan KumarОценок пока нет

- Microbiology of Ocular InfectionsДокумент71 страницаMicrobiology of Ocular InfectionsryanradifanОценок пока нет

- Nursing Care of ElderlyДокумент26 страницNursing Care of ElderlyIndra KumarОценок пока нет

- Mole Concept: Chemfile Mini-Guide To Problem SolvingДокумент18 страницMole Concept: Chemfile Mini-Guide To Problem SolvingNaren ParasharОценок пока нет

- 9 Oet Reading Summary 2.0-195-213Документ19 страниц9 Oet Reading Summary 2.0-195-213Vijayalakshmi Narayanaswami0% (1)

- Assessing Inclusive Ed-PhilДокумент18 страницAssessing Inclusive Ed-PhilElla MaglunobОценок пока нет

- Preferensi Konsumen &strategi Pemasaran Produk Bayem Organik Di CVДокумент8 страницPreferensi Konsumen &strategi Pemasaran Produk Bayem Organik Di CVsendang mОценок пока нет

- Requirement & Other Requirement: 2.311 Procedure For Accessing Applicable LegalДокумент2 страницыRequirement & Other Requirement: 2.311 Procedure For Accessing Applicable Legalkirandevi1981Оценок пока нет

- Abdul Khaliq - Good Governance (GG)Документ15 страницAbdul Khaliq - Good Governance (GG)Toorialai AminОценок пока нет

- Partial Defoliation of Vitis Vinifera L. Cv. Cabernet SauvignonДокумент9 страницPartial Defoliation of Vitis Vinifera L. Cv. Cabernet Sauvignon1ab4cОценок пока нет

- Personal Chiller 6-Can Mini Refrigerator, Pink K4Документ1 страницаPersonal Chiller 6-Can Mini Refrigerator, Pink K4Keyla SierraОценок пока нет

- Ficha Tecnica StyrofoamДокумент2 страницыFicha Tecnica StyrofoamAceroMart - Tu Mejor Opcion en AceroОценок пока нет

- Training and Supervision of Health Care WorkersДокумент12 страницTraining and Supervision of Health Care WorkerspriyankaОценок пока нет

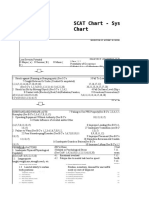

- SCAT Chart - Systematic Cause Analysis Technique - SCAT ChartДокумент6 страницSCAT Chart - Systematic Cause Analysis Technique - SCAT ChartSalman Alfarisi100% (1)