Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

How To Read A Book in Five Minutes PDF

Загружено:

Brian TranИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

How To Read A Book in Five Minutes PDF

Загружено:

Brian TranАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

How to read a book in five minutes Prof.

Margaret OMara

Its midterm season! Youve got papers due, exams to take, and you seem to be falling behind on

everything. And your history professor expects you to have that 250-page book with the really small

print finished by the end of the week! What the heck are you going to do?

a) Stay up until 3 a.m. reading every last word of that book, and fall asleep in class the next day

because youre so exhausted.

b) Read the first 35 pages, figuring youll read the whole thing someday when you have time. If

asked a question, figure out something really general to say.

c) Dont even bother to open the book. If you cant read the whole thing, whats the point?

Maybe the professor wont call on you.

The answer is, as you might guess, NONE OF THE ABOVE. Instead, learn some smart strategies about

how to read scholarly historical monographs and nonfiction books generally so that you can take

away the most important parts of the argument. Doing this properly will take MORE than five minutes

(but that title got your attention, didnt it?), but it still will save you time. And you might just learn

something.

STEP ONE - THE FIRST FIVE MINUTES

1. Judge a book by its cover

- What is the title?

- What is the subtitle? (the stuff that comes after the colon)

- What photos/illustrations are on the cover?

- What do these three pieces of data tell you about the WHO WHAT WHEN WHERE of

the book?

2. Turn the book over

- Who wrote the blurbs? (the advance praise in quotation marks on the back) Are they

professors? Are they history professors? Do their quotes give you any more clues?

o Remember: the content of the blurbs may not tell you the content of the book, but

they tell you who is willing to attest to the authors skills and insights

- Read the summary on the back. What does it tell you about the major THEMES of the book?

What does it say about how this book is DIFFERENT from other books on the same topic?

3. Read the publication information

- When was it first published? Was it published during or shortly after the period it discusses?

- Who is its author and does s/he have other publications? If so, about what?

4. Read the table of contents

- Looking at the title of each chapter, what can you tell about the historical ground covered by

the book? Who are its main characters? Where does it take place?

- Which of the chapters sound the most interesting to you?

5. Re-read your course syllabus

- How do the major themes of the class (that you glean from lecture titles, instructors

summary of the course, major themes of lectures, etc.) relate to the major themes of this

book? What clue does the syllabus give about why the professor assigned this book?

STEP TWO THE NEXT FIVE MINUTES

1. Scan the books footnotes/endnotes.

- What kinds of sources does the author use?

- Are these mainly primary or secondary sources? (Hint: in the introduction and conclusion,

there often tend to be more secondary sources. Concentrate on the notes for the middle

chapters of the book.)

2. Flip through the book and look at the photo illustrations, tables, charts, maps, etc. Authors have

to be choosy in selecting illustrations (partly because its expensive to include a lot of them).

This means that they tend to be closely related to the books main argument(s).

- Who are in the photos? What are they doing?

- If there are maps, what are they illustrating? What point is the author trying to make with

maps?

- How many charts and graphs and tables are in the book? Do these reflect quantitative

analysis by the author (like in an economics book, for example), or do they summarize other

data in a tabular form? Do you think the author is a number-cruncher?

3. Look at the index.

- Who and what have lots of page numbers by their entries?

- Note the five most important and frequently-mentioned characters and events. Make sure

you generally know who these are before you come to class. (For example, if you are

assigned a book on the New Deal and cant identify Frances Perkins, or tell the professor

why she is important, youve fallen short.

1

)

STEP THREE THE NEXT THIRTY MINUTES

1. Read the introduction. In works of history, the introduction is typically where the author tells

you WHO (individuals, groups) the book is about, WHAT happened to these people, WHEN it

happened, WHERE it happened, and WHY you should care. Often the author will give a brief

summary of the chapters to come and how they support the main argument.

- As you read, write up a page of brief notes to yourself answering the WHO-WHAT-WHEN-

WHERE-WHY.

- Note the main topic of each chapter, and remind yourself of the ones that sound the most

interesting to you.

- Figure out where the author stands vis-a-vis other books. How is the author engaging and

debating other historians? Does the author say s/he is agreeing with other historians?

Disagreeing? What is different about this book than others on the subject?

1

Frances Perkins served as Secretary of Labor from 1933 to 1945 and was the first woman to serve in the United

States Cabinet, as well as a key implementer of President Franklin D. Roosevelts economic and public welfare

programs.

STEP FOUR THE THIRTY MINUTES AFTER THAT

1. Read a chapter. Ideally, make it Chapter One. If time doesnt permit that, go to one of the

chapters you flagged earlier as an interesting topic.

- Who are the main characters in this chapter?

- What happened to them?

- Why did that happen?

- How does this part of the story support the authors thesis?

- What questions does the chapter raise for you? How does this story relate to the broader

themes of the course in which it is assigned?

- What does the author say in the concluding paragraph of the chapter? (Hint: This is often

where a summary of the chapter appears.)

2. IF, AND ONLY IF, YOU HAVE RUN OUT OF TIME TO DO ANYTHING ELSE: Skim the conclusion.

- What new conclusions does the author add that werent in the introduction?

- What conclusions does the author derive from the chapters that you didnt get a chance to

read?

- How do the conclusions relate to the other things you have read, discussed, and heard in

class lectures and discussion?

STEP FIVE REALLY READ THE BOOK

If you manage your time well, you CAN have time to read the entire book. Your professor assigned it

because he or she thought it was a good book that would be informative and enjoyable for students.

You may choose to disagree on the enjoyable part, but that doesnt mean that the author doesnt

have something worthwhile to say - - or that the professor wont hesitate to put something about the

book on the final exam. Professors understand that college students have big workloads, and we try our

best not to give you an unmanageable amount of reading. We assign the pages-per-week that we

believe you reasonably can finish.

As you read, TAKE NOTES and/or FLAG THE PASSAGES THAT YOU FIND IMPORTANT OR MEMORABLE.

This can be done by scribbling in the endpapers, tapping down notes on your laptop as you go, writing

on a separate piece of paper, sticking Post-its on the edges of papers, or just folding over the corners of

pages. Do whatever works best for you. Historical monographs and serious nonfiction books tend to be

densely packed with information; note-taking as you go will save time and effort at the end.

Starting off every history-reading experience with 70 minutes of smart, strategic reading will help you

get through whole books faster. It makes you better prepared to talk and write about their content and

arguments. Reading quickly for comprehension is an essential skill, in college and in real life. Go forth

and conquer.

Вам также может понравиться

- Andres Caracoles Drax Eletropaulo Gener Dom - Rep. Argentina U.K Brazil Chile CG CS CS LU CGДокумент13 страницAndres Caracoles Drax Eletropaulo Gener Dom - Rep. Argentina U.K Brazil Chile CG CS CS LU CGBrian Tran100% (1)

- Reset Model - 3 Factor ModelДокумент2 страницыReset Model - 3 Factor ModelBrian TranОценок пока нет

- Model 1 - CAPMДокумент2 страницыModel 1 - CAPMBrian TranОценок пока нет

- Exercise 1. Open GRETL and Capm - GDT Data File.: Coefficient Std. Error T-Ratio P-ValueДокумент3 страницыExercise 1. Open GRETL and Capm - GDT Data File.: Coefficient Std. Error T-Ratio P-ValueBrian TranОценок пока нет

- Chapter 2 - Exercise 1Документ2 страницыChapter 2 - Exercise 1Brian TranОценок пока нет

- Chapter2 SolutionsДокумент6 страницChapter2 SolutionsBrian TranОценок пока нет

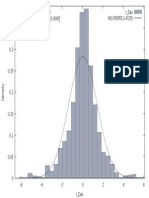

- Histogram of Daily Dax ReturnДокумент1 страницаHistogram of Daily Dax ReturnBrian TranОценок пока нет

- Bus 418 - Team 53Документ88 страницBus 418 - Team 53Brian TranОценок пока нет

- Exercise 1 - Chapter 4Документ4 страницыExercise 1 - Chapter 4Brian TranОценок пока нет

- Exercise 1 - Chapter 4Документ4 страницыExercise 1 - Chapter 4Brian TranОценок пока нет

- LOR Vicky For Reference 1 PDFДокумент1 страницаLOR Vicky For Reference 1 PDFBrian TranОценок пока нет

- Bill Clinton''s Great SpeechДокумент3 страницыBill Clinton''s Great SpeechBrian TranОценок пока нет

- IFRS Vs German GAAP Similarities and Differences - Final2 PDFДокумент87 страницIFRS Vs German GAAP Similarities and Differences - Final2 PDFBrian TranОценок пока нет

- (Harvard) Tesco Supply Chain Latest Version PDFДокумент30 страниц(Harvard) Tesco Supply Chain Latest Version PDFBrian TranОценок пока нет

- GMAT 4 Full Tests PDFДокумент174 страницыGMAT 4 Full Tests PDFBrian TranОценок пока нет

- Ex2 System PDFДокумент0 страницEx2 System PDFdejaytop19820% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (120)

- Group Discussion TopicsДокумент7 страницGroup Discussion TopicsRahul KotagiriОценок пока нет

- Odyssey of The West II - From Athens To Rome and The Gospels (Booklet)Документ69 страницOdyssey of The West II - From Athens To Rome and The Gospels (Booklet)Torcivia Leonardo67% (3)

- School Calendar 2010 - 11Документ11 страницSchool Calendar 2010 - 11Neil BradfordОценок пока нет

- Aspergers and Classroom AccommodationsДокумент14 страницAspergers and Classroom AccommodationssnsclarkОценок пока нет

- Powerpoint 2Документ14 страницPowerpoint 2api-406983345Оценок пока нет

- Table of Specifications and Test Questions ConstructionДокумент30 страницTable of Specifications and Test Questions ConstructionKathleen Grace MagnoОценок пока нет

- Kray-Leading Through Negotiation - CMR 2007Документ16 страницKray-Leading Through Negotiation - CMR 2007Rishita Rai0% (2)

- ICEP CSS - PMS Institute, Lahore (MCQ'S Gender Studies)Документ22 страницыICEP CSS - PMS Institute, Lahore (MCQ'S Gender Studies)Majid Ameer AttariОценок пока нет

- Young People, Ethics, and The New Digital MediaДокумент127 страницYoung People, Ethics, and The New Digital MediaThe MIT Press100% (28)

- Calculus Modules - Scope and SequenceДокумент13 страницCalculus Modules - Scope and SequenceKhushali Gala NarechaniaОценок пока нет

- The Folklore of Language Teaching. Thomas F. Magner (1965)Документ6 страницThe Folklore of Language Teaching. Thomas F. Magner (1965)Turcology TiranaОценок пока нет

- Division of Davao Del Norte Ooo Carmen National High SchoolДокумент2 страницыDivision of Davao Del Norte Ooo Carmen National High SchoolQueenie Marie Obial Alas100% (1)

- Orthodontics Principles and PracticeДокумент1 страницаOrthodontics Principles and PracticeAimee WooОценок пока нет

- GMF Project and RubricДокумент2 страницыGMF Project and RubriccaitilnpetersОценок пока нет

- Lesson PlanДокумент4 страницыLesson PlanCarlo MaderaОценок пока нет

- Post Colonialism Assignment 1Документ4 страницыPost Colonialism Assignment 1Ahsan RazaОценок пока нет

- Cambridge International AS Level: English General Paper 8021/12 February/March 2022Документ17 страницCambridge International AS Level: English General Paper 8021/12 February/March 2022shwetarameshiyer7Оценок пока нет

- Prof R Krishna Report On Credit Related Issues Under SGSYДокумент135 страницProf R Krishna Report On Credit Related Issues Under SGSYRakesh ChutiaОценок пока нет

- Untitledchaostheory PDFДокумент10 страницUntitledchaostheory PDFBob MarleyОценок пока нет

- Magna Carta For StudentsДокумент3 страницыMagna Carta For StudentsSarah Hernani DespuesОценок пока нет

- What Are The Major Distinction Between Storage and MemoryДокумент5 страницWhat Are The Major Distinction Between Storage and MemoryBimboy CuenoОценок пока нет

- Draft To Student Mse Oct 2014 - (Updated)Документ4 страницыDraft To Student Mse Oct 2014 - (Updated)Kavithrra WasudavenОценок пока нет

- Cot English 8 Composing Effective ParagraphДокумент5 страницCot English 8 Composing Effective ParagraphJerwin Mojico100% (9)

- Phenomenology Vs Structuralism DebateДокумент1 страницаPhenomenology Vs Structuralism DebateCristina OPОценок пока нет

- KS1 Crazy Character Algorithms Activity Barefoot ComputingДокумент8 страницKS1 Crazy Character Algorithms Activity Barefoot ComputingabisheffordОценок пока нет

- Annex 3 - Gap Analysis Template With Division Targets Based On DEDPДокумент15 страницAnnex 3 - Gap Analysis Template With Division Targets Based On DEDPJanine Gorday Tumampil BorniasОценок пока нет

- Editable Test Unit 4. Challenge LevelДокумент4 страницыEditable Test Unit 4. Challenge LevelNatalia RihawiiОценок пока нет

- Course Outline Pagtuturo NG Filipino Sa Elementarya IДокумент5 страницCourse Outline Pagtuturo NG Filipino Sa Elementarya IElma CapilloОценок пока нет

- Edcn 103 Micro StudyДокумент17 страницEdcn 103 Micro StudyYlesar Rood BebitОценок пока нет

- 3248 s12 Ms 1Документ5 страниц3248 s12 Ms 1mstudy123456Оценок пока нет