Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

NC165 05 Lorber PDF

Загружено:

مجدى محمود طلبهИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

NC165 05 Lorber PDF

Загружено:

مجدى محمود طلبهАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

A Revised Chronology for the

Coinage of Ptolemy I

1

CATHARINE C. LORBER

PTOLEMY, son of Lagus, employed a variety of coin types and several different

weight standards over the course of his long career as satrap and then as king.

The first great student of his coinage, J.N. Svoronos, believed that the Attic

standard remained in use until 305 BC, when the weights of both gold staters

and silver tetradrachms were reduced to provide a new coinage for Ptolemys

reign as king. Between 1960 and 1980 scholars examined the precious metal

coinage of Ptolemys satrapy and early kingship, and reached a consensus that

rejected Svoronos view. The main outlines of this consensus have scarcely been

questioned in the last quarter century. But when the present author attempted to

situate Ptolemys early bronze coinage within the existing chronological

framework, she encountered a contradiction that could be resolved only by

lowering the accepted date for Ptolemys first reduction of his weight standard.

That discovery triggered a review of the entire consensus chronology.

I. THE CONSENSUS CHRONOLOGY

In a study published in 1967, O.H. Zervos arranged Ptolemys early, Attic-

weight tetradrachms into annual issues dated from c.326 to c.310 BC.

2

Zervos

concluded that from Issue V through Issue XI, tetradrachms with standard

Alexander types were accompanied by a second series of tetradrachms featuring

a new obverse type, the head of the deified Alexander in an elephant headdress.

Issue XII (c.315) was transitional, retaining the Zeus reverse of the earlier

coinage, but introducing a redesigned Alexander head with a scaly aegis. In

addition, Ptolemys personal emblem, an eagle perched on a thunderbolt,

appeared as an adjunct symbol on the reverse. (Both of these would remain

regular features of the tetradrachm until the Alexander head was replaced by

Ptolemys portrait on his final royal currency.) Issues XIIIXVII bear a new

reverse type, a figure of Athena Alkidemos advancing right. Zervos ending date

of c.310 coincided with the date previously proposed for Ptolemys first

reduction of his weight standard.

1

The author is grateful to Wolfgang Fischer-Bossert for reading and commenting on an earlier

version of the manuscript. The conclusions offered here (and any errors) are her own.

2

O.H. Zervos, The early tetradrachms of Ptolemy I, ANSMN 13 (1967), pp. 116.

CATHARINE C. LORBER 46

Ptolemys second coinage of Alexander/Athena tetradrachms was struck at a

weight of about 15.70 g. In 1954 B. Emmons demonstrated that this weight

reduction was effected by trimming about 1.5 g of silver from tetradrachms of

Attic weight and then overstriking them, a process that allowed the Crown to

mint nine tetradrachms from the silver formerly required for eight.

3

Emmons

followed Svoronos in dating this reform c.305, but other scholars, notably A.B.

Brett and G.K. Jenkins, advocated a date of c.312 or 310.

4

Jenkins analysis was

especially influential. He divided the reduced-weight tetradrachms into seven

groups, groups af without corresponding gold and group g with control-linked

gold staters of the Ptolemy/elephant quadriga type. Jenkins pointed out the

chronological significance of the Chiliomodi hoard (IGCH 85), which contained

21 examples of groups ad.

5

This hoard was deposited at the end of the

Ptolemaic occupation of Corinth, in 306 according to O.E. Ravel (followed by

Jenkins and the editors of IGCH).

6

Jenkins thus reasoned that groups ad must

have been produced before 306, excluding Svoronos date of c.305 for the

reduction of the weight standard. The reintroduction of gold coinage provided

another chronological fixed point. Jenkins regarded 305 as the only possible

starting date for the staters issued in the name of King Ptolemy and bearing his

diademed portrait on the obverse.

7

Jenkins allowed half a decade (c.310305)

for production of the reduced-weight tetradrachms without corresponding gold,

while demurring that they may have begun as early as 312, and another half

decade (c.305300) for the gold staters and their accompanying tetradrachms.

8

O. Mrkholm later challenged the date of the Chiliomodi hoard, pointing out

that the ancient authors do not describe the end of the Ptolemaic occupation of

Corinth.

9

The Ptolemaic garrison at Sicyon surrendered to Demetrius

Poliorcetes in 303, after which Demetrius proceeded to Corinth, which was held

at the time by Prepelaus, a general of Cassander.

10

Mrkholm suggested that the

Ptolemaic occupation of Corinth could have lasted until 305 or even 304 and

3

B. Emmons, Overstruck coinage of Ptolemy I, ANSMN 6 (1954), pp. 6984.

4

Emmons, Overstruck coinage, pp. 6970; A.B. Brett, The aphlaston, symbol of naval victory

or supremacy on Greek and Roman coins, Transactions of the International Numismatic Congress,

London, 1936 (London, 1938), pp. 2332, especially p. 26; G.K. Jenkins, An early Ptolemaic hoard

from Phacous, ANSMN 9 (1960), pp. 1737, see especially pp. 325.

5

Jenkins, Phacous, pp. 323.

6

O.E. Ravel, Corinthian hoard from Chiliomodi, Transactions of the International Numismatic

Congress. London, 1936 (London, 1938), pp. 98108; Jenkins, Phacous, pp. 323. Zervos, The

Delta hoard of Ptolemaic Alexanders, 1986, ANSMN 21 (1976), p. 58, proposed a different

interpretation of the Chiliomodi hoard, namely that it was formed after a ban on Attic-weight silver

promulgated in Egypt in 305. It is unclear why a Ptolemaic policy designed to create a closed

currency market in Egypt should have affected hoard formation in the Peloponnesus. Jenkins view

of the hoard is the more persuasive.

7

Jenkins, Phacous, p. 33.

8

Jenkins, Phacous, pp. 345.

9

O. Mrkholm, Cyrene and Ptolemy I: Some numismatic comments, Chiron 10 (1980), p. 156.

10

Diod. 20.102.13, 20.103.1.

A REVISED CHRONOLOGY OF THE COINS OF PTOLEMY I 47

proposed redating the Chiliomodi hoard to c.304.

11

He submitted that Jenkins

groups e and f (reduced-weight tetradrachms without corresponding gold, not

represented in Chiliomodi) might be dated c.305303, while the tetradrachms

with corresponding gold (group g) should be dated c.303298/7.

12

His new

terminal date for group g was based on the production of a few

Ptolemy/elephant quadriga gold staters at Cyrene, which was in revolt against

Ptolemy c.305c.300.

13

When it comes to the introduction of Ptolemys standardized royal coinage,

the consensus breaks down. Jenkins assumed that his group g was immediately

followed (c.300) by a major overhaul of the currency, which introduced royal

portrait/eagle types for both gold and silver, reduced the weight of the

tetradrachm to c.14.2 g, and replaced the gold stater with a heavier

denomination, the trichryson or triple stater.

14

Adhering to the theory of E.S.G.

Robinson that the process of weight reduction occurred in a series of successive

small steps, Mrkholm proposed an intervening period (c.298295/0) when

only Ptolemy/eagle tetradrachms of c.14.9 g were minted; after this phase the

weight of the tetradrachm was finally reduced to c.14.2 g and new

denominations were introduced in gold, silver, and bronze.

15

A. Davesne cited

control links between the tetradrachms of c.14.9 and c.14.2 g and argued that

they were too numerous and systematic to recur in succeeding periods, so that

tetradrachms on these two different weight standards must have been

contemporary.

16

Based on a theory of annual emissions exhibiting regular

weight loss through circulation, he arrived at a date of c.295/4 for the beginning

of the reformed coinage with Ptolemy/eagle types.

17

II. REVISED CHRONOLOGY OF THE ATTIC-WEIGHT COINAGE

There are several reasons to suspect that the consensus chronology for

Ptolemys Attic-weight tetradrachms may be too high.

11

Mrkholm, Cyrene and Ptolemy I, p. 156; id., Early Hellenistic Coinage from the Accession of

Alexander to the Peace of Apamea (336188 B.C.) (Cambridge, 1991), p. 65.

12

Mrkholm, Cyrene and Ptolemy I, p. 156.

13

Mrkholm, Cyrene and Ptolemy I, pp. 154 and 155f.

14

G.K. Jenkins, The monetary systems in the early Hellenistic time with special regard to the

economic policy of the Ptolemaic kings, in A. Kindler (ed.), The Patterns of Monetary Development

in Phoenicia and Palestine in Antiquity, Proceedings, International Numismatic convention,

Jerusalem, 2731 December 1963 (Tel Aviv/Jerusalem, 1967), p. 62. The term trichryson is attested

by P. Zen. Cair. 59022, ll. 1617.

15

E.S.G. Robinson, The coin standards of Ptolemy I, in M. Rostovtzeff, The Social and

Economic History of the Hellenistic World (Oxford, 1941), vol. 3, pp. 16359; Mrkholm, Cyrene

and Ptolemy I, p. 158 (where the dates are c.298290); id., Early Hellenistic Coinage, p. 66 (where

the dates c.298295 are implied).

16

A. Davesne and G. Le Rider, Le Trsor de Meydancikkale (Cilicie Trache, 1980), Glnar II

(Paris, 1989), pp. 2712.

17

Davesne, Meydancikkale, pp. 2734.

CATHARINE C. LORBER 48

First, Zervos followed E.T. Newell in dating the earliest Alexander-type

coinage of Egypt c.326.

18

Newell suggested this date because he believed that

the depiction of Zeus with his legs crossed was an innovation of Alexandria,

promptly imitated at Sidon where the new type first appeared on tetradrachms

dated 325/4. But G. Le Rider recently argued that the influence was more likely

to have flowed in the opposite direction, because tetradrachms from Phoenicia,

and especially from Sidon, entered Egypt in large numbers, whereas relatively

few Egyptian tetradrachms appear to have circulated outside the country. If

Sidonian tetradrachms were the prototypes, the first Egyptian Alexanders were

struck no earlier than 325/4.

19

Second, the Demanhur hoard (IGCH 1664) contained examples of Zervos

Issues II through VI, but no later issues. It is clear that Zervos Issue VI must

have been placed in circulation very shortly before the hoards closure. Yet

Zervos dated his Issue VI to 321, though Newell estimated the closure of

Demanhur at 318 or 317 on the very sound basis that the latest dated coins of

Sidon and Ake were of 319/18 and 318/17 respectively.

20

If we accept Zervos

hypothesis of annual emissions in Egypt, the evidence of the Demanhur hoard

suggests that all of his dates should be lowered by three or four years. (The

Appendix, examining the consequences for specific Ptolemaic issues, shows

that the correct figure is three years.) This downdating extends the assumed

annual issues of Attic-weight Palladion tetradrachms to c.307.

21

Finally, Zervos omitted two issues of Attic-weight Palladion tetradrachms,

Svoronos 39 and 40. Based on the number of surviving examples, these appear

to have been small and insignificant emissions.

22

But the same is true of Zervos

two final issues, Issues XVI and XVII.

23

The apparently small size of all four

emissions probably reflects a low survival rate, due to the fact that these

emissions were disproportionately affected by the recoining effort described by

Emmons. If Svoronos 39 and 40 are assumed to be annual issues, the Attic

standard could have remained in use as late as c.305, just as proposed by

Svoronos and Emmons. Of course, the hypothesis of annual emissions, though

plausible, still remains an unproved supposition, but we shall see below that

there is independent evidence supporting a date around 305 for the introduction

of the reduced weight standard.

18

E.T. Newell, Alexander Hoards II: Demanhur, 1905 (New York, 1923), p. 64.

19

G. Le Rider, Clomne de Naucratis, BCH 121 (1997), pp. 878.

20

Newell, Demanhur, 3768 and 39725.

21

The term Palladion tetradrachms was employed by Zervos in Delta hoard, pp. 40 and passim.

It is gratefully adopted here to avoid the more specific but unwieldy terms Attic-weight

Alexander/Athena tetradrachms and reduced-weight Alexander/Athena tetradrachms.

22

Svoronos 39 lists 2 specimens, to which can be added Leu 22, 89 May 1979, lot 173; Svoronos

40 lists 1 specimen.

23

Zervos cited 3 specimens of his Issue XVI; Zervos Issue XVII is Svoronos 37, where 3

specimens are listed.

A REVISED CHRONOLOGY OF THE COINS OF PTOLEMY I 49

III. EARLY BRONZE COINAGE IN THE NAME OF PTOLEMY

None of the modern scholarship treating the chronology of Ptolemys precious

metal coinage took note of his early bronze issues. As a result we have

overlooked connections, already published by Svoronos, that provide critical

evidence for dating the reduced-weight Palladion tetradrachms.

The earliest bronze coins to bear Ptolemys name are about 15 mm in

diameter, with the obverse type horned head of Alexander with long hair,

wearing a mitre, and the reverse type eagle with spread wings standing left on

thunderbolt. These coins were issued in three series, two of which bear military

symbols as series markers. The Helmet Series features a Corinthian helmet

symbol in left field with a second control above, and a legend naming King

Ptolemy.

24

The beginning of the Helmet Series bronzes can thus be dated with

certainty after Ptolemys assumption of the diadem in late 305 or early 304.

25

The Aphlaston Series is marked by an aphlaston symbol, sometimes with a

second symbol or control letters below. The Plain Series has no identifying

symbol but bears letter or monogram controls that link it convincingly to the

Ptolemy/elephant quadriga gold staters, issued in the name of King Ptolemy,

and/or to their associated Palladion tetradrachms, still issued in the name of

Alexander (see Table 1). Both the Aphlaston Series and the Plain Series bronzes

bear legends naming Ptolemy, but without his royal title.

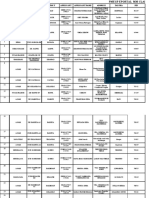

TABLE 1.

Bronze coinage after 305/4, with control links

Helmet Series

tetradrachms

Helmet Series Aphlaston Series

Plain Series Gold staters

AAEEANAPOY HTOAEMAIOY

BAZIAEOZ

HTOAEMAIOY HTOAEMAIOY HTOAEMAIOY

BAZIAEOZ

k//Helmet Aphlaston/Helmet

Helmet/t t/Helmet

Aphlaston

Helmet// //Helmet

Aphlaston/z z

Helmet/! !/Helmet / /

|/Helmet

./

Grapes/Helmet

J/

24

Svoronos 163, 167, 170A, 171, and 173.

25

The ancient historiographers place Ptolemys elevation in the aftermath of the battle of Salamis,

thus in 306: see App. Syr. 54, Diod. 20.53.3, and Plut. Demetr. 18.2. But the date 305/4 is attested by

the Marmor Parium (FGrHist 239 F B 23), and various Egyptian documents place the beginning of

Ptolemys reign in late 305 or early 304, e.g., P. dem. Louvre 2427, 2440 (6 January 304); Canon.

Ptol. at Ptolemaou Lgou (7 November 3056 November 304). A.E. Samuel, Ptolemaic

Chronology (Munich, 1965) pp. 411, narrowed the range to 7 November 3051 February 304 but

argued that the actual date was 7 November 305, equivalent to 1 Thoth, New Years Day of the

Egyptian calendar. For an updated list of references treating the evidence for the date when Ptolemy

assumed the royal title, see W. Hu, gypten in hellenistischer Zeit 33230 v.Chr. (Munich, 2001), p.

191 n. 747.

CATHARINE C. LORBER 50

Helmet Series

tetradrachms

Helmet Series Aphlaston Series

Plain Series Gold staters

/

7

!/

/

(tetradrachm)

/

! !P

!

/

Aphlaston/

!

+ 7

*

*

Occurs both without royal title (Svoronos 136) and with it (Malter II, 2324

February 1978, lot 5; ANS 1944.100.75794)

The three bronze series were not strictly contemporary. While the Plain Series

bronzes are control linked to the Ptolemy/elephant quadriga gold staters and

thus to Jenkins group g, three of six known varieties of Helmet Series bronzes

share their controls with reduced-weight Palladion tetradrachms without

corresponding gold.

Tetradrachms Jenkins group Bronzes

Helmet above t (Sv. 170)

Group d

t above helmet (Sv. 170A)

Helmet above / (Sv. 162)

Group e

/ above helmet (Sv. 163)

Helmet above !

Group e

! above helmet (Sv. 167)

The last of these silver issues is not well attested. Jenkins listed it among the

varieties of his group e, but he cited Svoronos 167, the corresponding bronze.

26

Nevertheless, the other two links establish an absolute date after Ptolemys

assumption of the kingship (late 305/early 304) for the tetradrachms involved

and, by extension, for other tetradrachms of Jenkins groups d and e. These links

confirm the low chronology proposed by Mrkholm for groups e and f.

Arguably, they also exert downward pressure on groups ad.

26

Jenkins, Phacous, p. 34.

A REVISED CHRONOLOGY OF THE COINS OF PTOLEMY I 51

IV. REDUCED-WEIGHT PALLADION TETRADRACHMS WITHOUT

CORRESPONDING GOLD: THE PLAIN AND HELMET SERIES

The Delta hoard of 1896 (IGCH 1671) consisted exclusively of reduced-

weight Palladion tetradrachms without corresponding gold (Jenkins groups af).

In his reconstruction and penetrating study of the Delta hoard, Zervos divided

these tetradrachms into five series, identified the hands of three artists (A, B,

and C), and further identified three styles for each artist (1, 2, and 3).

27

He

concluded that the five series were minted concurrently rather than sequentially,

an important finding that collapses the time frame necessary for production of

Jenkins groups af. Zervos wrote that the correlation of the five series cannot

be known very precisely.

28

Despite his warning we shall try to develop a more

nuanced picture of this coinage, drawing in part on varieties that were not

represented in Zervos material.

Table 2 lists the known emissions of reduced-weight Palladion tetradrachms

without corresponding gold. The relative size of the various emissions is

approximately indicated by figures in brackets, the first giving the number of

specimens listed by Svoronos and the second the number in Zervos Delta hoard

reconstruction. To the extent possible, Jenkins group is cited, followed by

Zervos artist and style designations. Artists and/or styles not assigned by

Zervos, but evidenced by specimens published elsewhere, are noted

parenthetically. The sequence of issues within each series reflects the successive

styles of Zervos three artists, with one exception, explained below. The table is

transected by a bar representing the closure of the Chiliomodi hoard. The

distribution of issues above and below this bar is to some slight degree

conjectural. It depends on the assumption that issues of moderate size, with a

dozen or more examples recorded by Svoronos, should have been represented in

Chiliomodi if struck before its closure. Smaller issues have been placed

according to control linkage and/or artist and style.

27

Zervos, Delta hoard, pp. 467.

28

Zervos, Delta hoard, p. 47.

CATHARINE C. LORBER 52

TABLE 2.

Alexander/Athena tetradrachms of reduced weight

Plain series Helmet series

( +

?

Svor. 110 [18]

Delta hoard [3

*

]

Jenkins: a

Zervos: A1, A2

*

in Chiliomodi

+

Svor. 109 [1]

Jenkins: b

? Aphlaston

Svor. 154 [8]

Delta hoard [1

*

]

Jenkins: a

Zervos A1

*

+/Bee

Svor. 153 [14]

Delta hoard [2]

Jenkins: b

Zervos: C1

in Chiliomodi

7?

Svor.

Kuft hoard, Nash, NC

1974, p. 25 [1]

(?z

Svor. 145 [9]

Delta hoad [3

*

]

Jenkins: a

Zervos: B1

(also Artist/style B2)

in Chiliomodi

+/Helmet<

Svor. 161 [4]

Delta hoard [1]

Jenkins: b

Zervos: C1

7 / ?

Svor. 146 [41]

Delta hoard [12]

Jenkins: a

Zervos: A1

in Chiliomodi

Helmet?

Svor. 168 [57]

Delta hoard [15

*

]

Jenkins: a

Zervos: A2

(second artist

**

)

in Chiliomodi

overstruck

(/2

Svor. 140 [1]

Jenkins: a

+/Cornucopia<

Svor. 159 [2]

Delta hoard [1]

Jenkins: b

Zervos: C1

*Helmet/?

Svor. 175 [1]

Commerce

Jenkins: e?

(Artist/style B2)

(!

Svor. 144 [1]

+/Bee<

Svor. 158 [2]

(Artist/style C1)

Helmet/t

Svor. 170 [41]

Delta hoard [10]

Jenkins: d

Zervos: A2

in Chiliomodi

overstruck

Svor. 107 [26]

Delta hoard [9

*

]

Jenkins: c

Zervos: A2/B, B2,

B3

in Chiliomodi

z(

Svor. 143 [7]

Delta hoard [2]

Jenkins: a

Zervos: B3

+/Dolphin<

Svor.

Delta hoard [1]

Jenkins: b

*Helmet/t

Svor. 174 [17]

Delta hoard [4]

Jenkins: d

Zervos: A2

overstruck

Helmet/

Svor. 166 [7]

Delta hoard [2]

Jenkins: c

Zervos: A2/A,

B2/A

(z

Svor. 141 [3]

Delta hoard [8]

(Artist/style B2,

with z

***

)

Svor. 142 [24]

Delta hoard [9

*

]

Jenkins: a

Zervos: B2, B3

in Chiliomodi

+<

Svor. 139 [64]

Delta hoard [13]

Jenkins: b

Zervos: C1, C2, C3

(also Artist/style B2)

in Chiliomodi

Chiliomodi hoard closes 304 or early 303 B.C.

A REVISED CHRONOLOGY OF THE COINS OF PTOLEMY I 53

Plain series Helmet series

( +

Helmet/!

Svor. 165 [12]

Delta hoard [4]

Jenkins: e

Zervos: A2

overstruck

Helmet/!

Svor.

Jenkins: e

!

Svor. 108 [14]

Delta hoard [8

*

]

Jenkins: e

Zervos: A2

overstruck

Helmet//

Svor. 162 [62]

Delta hoard [27]

Jenkins: e

Zervos: A2, A3

overstruck

z!

Svor. 137 [3]

Delta hoard [1]

Jenkins: e

Zervos: A3

Helmet/t

Svor. 164 [37]

Delta hoard [13]

Jenkins: e

Zervos: A2, A3

overstruck

zHelmet

Svor. 180 [1]

(Artist/style A3)

zHelmet/

Svor. 179 [6]

Delta hoard [1]

Jenkins: f

Zervos: A3

Helmet/z

Svor. 169 [26]

Delta hoard [11]

Jenkins: f

Zervos: A3

overstruck

UHelmet/z

Svor. 177 [10]

Delta hoad [3

*

]

Jenkins: f

Zervos: A3

overstruck

Pellet

Helmet/z

Svor. 176 [5]

(Artist/style A3)

<Helmet/z

Svor. 178 [1]

Delta hoard [1

*

]

Zervos A3

*

Obverse dies link.

*

Includes specimens cited by Zervos, ANSMN 23, p. 50 note a.

**

See Svoronos pl. vi, 7.

Obverse die link.

***

See Svoronos pl. A,21.

CATHARINE C. LORBER 54

Zervos considered the Plain Series and the Helmet Series to comprise the

large regular issue of Alexandria.

29

He attributed all of their dies to the

mints principal engraver, A, on the assumption that the tiny z concealed among

the scales of the aegis was his signature. An artist attribution made solely on the

basis of this signature should be treated with scepticism. The reverse dies of A

show great consistency throughout both the Plain Series and the Helmet Series,

but there is a sharp contrast between obverse dies of style 1 and style 2. Zervos

reported both styles in the Plain Series issue bearing the monogram ?.

30

This

monogram was identified by Brett as the point of transition from the Attic to the

reduced standard; Jenkins concurred, noting the stylistic similarity between

Attic- and reduced-weight tetradrachms marked with ? (Svoronos 37 and

110); and Zervos associated both in his annual Issue XVII.

31

But the notion of

artistic evolution within a single year is scarcely tenable.

32

The obverse dies

designated A1 and A2 must instead represent the work of two different

engravers.

The Helmet Series also begins with issues bearing the monogram ?. The

control link to the early issues of the Plain Series suggests that the two series

commenced around the same time. A nearly simultaneous inauguration of both

series is supported by the fact that artist A2, after cutting dies for the first issue

of the Plain Series, became the principal obverse die engraver of the Helmet

Series, while A1 cut the obverse dies for the other early issues of the Plain

Series.

33

The Plain Series shrinks in importance next to the Helmet Series, which

comprised many more emissions, a number of them quite large. Yet only two

issues of the Helmet Series were represented in the Chiliomodi hoard. The

second of these (Svoronos 170) bears the controls helmet and t which, as we

have seen, also appear together on Helmet Series bronzes with a legend naming

Ptolemy as king (Svoronos 170A). This control link dates the helmet /t

tetradrachms after Ptolemys coronation in late 305/early 304. This in turn fixes

the deposit of Chiliomodi in 304 (or perhaps even early 303, to allow time for

the coins to travel to Greece). Some very large issues of the Helmet Series

(Svoronos 162 and 164) were not represented in the Chiliomodi hoard, making

it a virtual certainty that they were minted after its closure. Both Jenkins and

Zervos stylistic classifications place many emissions after Svoronos 162 and

29

Zervos, Delta hoard, p. 46.

30

O.H. Zervos, A Ptolemaic hoard of Athena tetradrachms at ANS, ANSMN 23 (1978), p. 50

note a.

31

Brett, Aphlaston, TINC, p. 26; Jenkins, Phacous, p. 33; Zervos, Early tetradrachms of

Ptolemy I, pp. 7 and 15; id., Delta hoard, p. 48.

32

I owe this observation to Wolfgang Fischer-Bossert.

33

A third artist appears to have cut at least one obverse die for the first issue of the Helmet Series,

see Svoronos, pl. vi, 7.

A REVISED CHRONOLOGY OF THE COINS OF PTOLEMY I 55

164, meaning that the greater portion of the Helmet Series was struck after

c.304.

The late date for the helmet/t tetradrachms also exerts downward pressure

on the only large issue that preceded it, marked helmet/? (Svoronos 168). It is

hard to see how this emission could be dated earlier than 305. If, as seems

likely, the Plain Series commenced simultaneously, the four early issues bearing

the monogram ? must also be dated c.305.

V. REDUCED-WEIGHT PALLADION TETRADRACHMS WITHOUT

CORRESPONDING GOLD: THE (, , AND + SERIES

Zervos characterized the ( Series as part of a smaller special issue of

Alexandria, because all of the examples in the Delta hoard were the work of a

new engraver, B. The hallmarks of his obverse style are a peculiar arching fold

in the elephant headdress, in a position occupied by the lions ear on coins of

Alexander type; a scalloped arc outlining the ear of the deified Alexander, a

form that represents the lions lip on coins of Alexander type; and two snakes

rising prominently from the aegis, approximating the outline of a lyre, as on the

early type of Alexander head employed with the Zeus reverse in Zervos Issues

VXI; in addition, the outline of the aegis is often dotted. The first two of these

distinctive details derive from silver coinage of Alexander type, from which we

can deduce that artist B was unacquainted with the current iconography of

Ptolemaic coins. Probably he had been cutting dies for Alexander-type

tetradrachms somewhere outside Egypt before being recruited for the (

Series.

The control ? links the first issue of the ( Series with early issues of the

Plain and Helmet Series, presumably indicating that the ( Series began around

the same time. Svoronos 142, with dies by artist B in his latest style, was

represented in the Chiliomodi hoard. Evidently the ( Series terminated shortly

before the Ptolemaic evacuation of Corinth (or shortly after, if Svoronos 143

was post-Chiliomodi).

Zervos characterized the very brief Series (Jenkins group c) as another

part of Alexandrias special issue because it combines the hands of two artists,

the main engraver of the reduced-weight coinage, A, and the engraver of the (

Series, B. The collaborative character of the Series is further underlined by

the appearance of the helmet symbol on one of its issues (Svoronos 166). The

styles of artist B represented in the Series suggest it was roughly

contemporary with the end of the ( Series; it is even possible that the

Series was a continuation of the ( Series, though its separate control seems to

suggest otherwise.

Zervos regarded the + Series (Jenkins group b) as the third part of

Alexandrias special issue. He attributed all of its dies to yet another engraver,

C. The + Series is further distinguished from other series of reduced-weight

CATHARINE C. LORBER 56

Palladion tetradrachms by the use of variable symbols as secondary controls.

34

Zervos sequence of styles establishes that the + Series was complete, or

essentially so, by the deposit of the Chiliomodi hoard. The present author

disagrees, however, with Zervos attribution of the entire + Series to artist C.

The obverse die illustrated in ANSMN 21, pl. viii, 6 appears to be the work of

artist B. It displays three of his hallmarks, the faux ear, the lions lip

transplanted to the elephants mouth, and the dotted edge of the aegis. Many

other published examples of this largest emission of the + Series (Svoronos

139) were struck from obverse dies of artist B.

35

In fact, it appears that the

majority of the obverse dies for this emission were cut by artist B, with artist C

contributing only a minority. Yet more remarkable, two dies of artist B show a

tiny z concealed in the scales of the aegis.

36

This letter has been supposed to be

an artists signature, but its presence on dies of artist B refutes that belief and

indicates that the letter must have had a control function of some sort.

37

Our

analysis of Zervos special issues yields a group of striking coincidences. Each

of the three series came to an end around the time Ptolemy was forced to

surrender Corinth, in 304 or early 303. Each either concluded with an

exceptionally large issue, or involved an exceptionally large issue near its end;

and two of the three required the services of a second die engraver for their final

issues.

VI. CHRONOLOGY AND PROCESS OF PTOLEMYS

FIRST METROLOGICAL REFORM

Our review of the chronology of Ptolemys Attic-weight coinage found that it

probably ended c.305. Control links between early reduced-weight Palladion

tetradrachms and bronzes issued in the name of King Ptolemy imply a date

c.305 for introduction of the reduced weight standard. Almost certainly, then,

the reduction of the standard occurred c.305. The many issues of Helmet Series

tetradrachms produced after the closure of the Chiliomodi hoard imply that the

34

It is true that several symbolsaphlaston, helmet, and starappear on certain issues of other

series, but their function is not clear. The first two may be military symbols rather than controls.

35

Mrkholm, Early Hellenistic Coinage, pl. iv, 93; H.-C. Noeske, Die Mnzen der Ptolemer:

Historisches Museum Frankfurt am Main (Frankfurt, 2000), no. 3 (with z); Naville 1 (1921, Pozzi),

3188-90 (last with z); SNG Manchester 1410. The authors photo file yielded three additional

obverse dies of artist B.

36

Svoronos 141, an issue of the ( Series, is described as having z on the aegis. The illustrated

example, Svoronos pl. A, 21, features an obverse die by artist B but the z is not clearly visible.

Svoronos description is now vindicated by these other dies of artist B with z on the aegis.

37

See also R.H.J. Ashton, Classical Review 47 (1997), p. 226 (review of Blanche Brown, Royal

Portraits): On pp. 28-9 B. follows current orthodoxy in regarding the tiny letter delta found on

some early obverse dies of Ptolemy I as the signature of an engraver of rare versatility. However, in

the latest arrangement of the coinages of Ptolemy I and II (A. Davesne/G. Le Rider, Le trsor de

Meydancikkale, Paris 1989, esp. p. 178) the letter also appears on dies used in the 250s; the spread

of 60 or so years which this entails seems too long for the professional life of a single artist.

A REVISED CHRONOLOGY OF THE COINS OF PTOLEMY I 57

reintroduction of gold coinage was delayed until some time after 303. The

consensus chronology estimated a period of five to seven years for the

production of reduced-weight tetradrachms without corresponding gold.

38

It

may now be possible to establish the terminal date of this phase with more

precision.

The metrological reform was accompanied by administrative changes that

tend to obscure the chronology. The old pattern, in which most coins bore only

one monogrammatic or letter control, fit neatly with Zervos hypothesis of

annual magistracies for the Attic-weight coinage. The reduced-weight

tetradrachms, in contrast, often bear two or even three such controls.

Nevertheless, the Helmet Series, the main series of the Alexandria mint, seems

to retain the old pattern of a single signature on its early issues. On the

assumption of continuing annual magistracies at Alexandria, the issues can be

dated as follows:

? c.305 (Macedonian year 306/5)

t c.304 (Macedonian year 305/4)

! c.303 (Macedonian year 304/3)

/ c.302 or 301 (Macedonian year 303/2 or 302/1)

t c.302 or 301 (Macedonian year 303/2 or 302/1)

z c.300 (Macedonian year 301/300)

z c.299 (Macedonian year 300/299)

The control ! is omitted here because the issue is highly doubtful. The two

late issues of the Plain Series (Svoronos 108 and 137), marked with the control

!, may also represent an annual emission. Zervos stylistic designations

suggest that they were contemporary with middle issues of the Helmet Series;

possibly they were produced concurrently c.302 or 301, but if they interrupted

the Helmet Series (or even followed it?), they could extend this phase of mint

activity to c.298. The additional signatures associated with the letters z

anticipate the control system of the next phase of the coinage, comprising gold

staters and control-linked Palladion tetradrachms, which normally bear two or

three monograms and do not seem remotely amenable to an arrangement into

annual emissions.

A date around 305 for the introduction of the reduced weight standard accords

with the long-discarded chronology of Svoronos and Emmons. Emmons drew

attention to the near-destruction of the Ptolemaic fleet in the battle of Salamis in

306, to Ptolemys loss of his overseas revenues, to his offer of handsome bribes

to soldiers willing to defect from Antigonus in the winter of 306/5 (a talent for

38

Jenkins, Phacous, p. 35 (310305 or 312305); Zervos, Early tetradrachms of Ptolemy I, p. 7

(310305); id., Delta hoard, pp. 537 (312/10305/4); Mrkholm, Cyrene and Ptolemy I, pp.

1568 (310303).

CATHARINE C. LORBER 58

officers, two minae for common soldiers

39

), and to his aid to Rhodes during

Demetrius thirteen-month siege (305/4).

40

She concluded that the conjunction

of high expenses and low revenues caused a financial strain, indeed an

emergency, to which Ptolemy responded by reducing the weight of his

tetradrachms.

41

In the consensus chronology, the weight reduction was viewed as a first step

in creating Egypts famed closed economy. Other steps included a later ban on

the entry of foreign silver coinage and perhaps an official ban on the use of

Ptolemys old Attic-weight silver within Egypt. Jenkins pointed out that

Egyptian hoards contain no Attic-weight silver datable later than 305, but

subsequently suggested that the influx of foreign coin stopped c.300.

42

Given

that Ptolemys first weight reduction involved the recoining of Attic-weight

tetradrachms, and given that it was apparently motivated by a fiscal crisis, it

makes sense that he would have acted earlier rather than later to establish

mechanisms at the ports of entry to enforce the exchange of Attic-weight

tetradrachms for his new reduced-weight tetradrachms so as to capture the

former for recoining. It thus seems quite likely that import controls were

implemented c.305, just as the hoards imply, and that the weight reduction and

the ban on importing foreign currently were conceived together as parts of a

single policy.

43

Emmons believed that the reform of c.305 involved the recall of

all Attic-weight tetradrachms and their immediate reduction, restriking, and

reissue.

44

The evidence developed here, however, indicates that the recoining

process required several years to complete, suggesting that the Attic-weight

coinage may have been withdrawn gradually by bankers and money changers,

avoiding the trauma of a sudden recall. Jenkins and Zervos, though wrong on

the chronology, were probably right to suggest that Attic- and reduced-weight

tetradrachms circulated side-by-side for half a decade before the heavier

coinage was banned entirely.

45

It seems logical that the proliferation of series of reduced-weight tetradrachms

should reflect intense mint activity arising from the practical needs of currency

reform. Indeed, Zervos documented a surge in the output of tetradrachms and

cited the hiring of two extra die engravers as evidence of the work overload

during this period, though he attributed the heightened mint activity to a need

39

Diod. 20.75.1.

40

Emmons, Overstruck coinage, p. 80.

41

Emmons, Overstruck coinage, pp. 81, 83.

42

Jenkins, Phacous, pp. 312; id., Monetary systems, p. 59.

43

Simultaneous introduction of both measures risked creating an imbalance between the supply of

reduced-weight tetradrachms and the demand for the new currency by foreign merchants, but, as is

indicated by P. Cairo Zen. 59021, such problems of currency reform had still not been ironed out by

the twenty-eighth regnal year of Ptolemy II.

44

Emmons, Overstruck coinage, pp. 71, 778, 81, 83.

45

Jenkins, Phacous, pp. 367; Zervos, Delta hoard, pp. 525.

A REVISED CHRONOLOGY OF THE COINS OF PTOLEMY I 59

to compensate for the gold staters that were no longer being minted.

46

Close

examination of the five series of reduced-weight tetradrachms reveals surprising

nuances.

The relation of the Plain Series and the Helmet Series, both signed by the

magistrate ? in the first year of the reform, is unclear. Possibly the Helmet

Series succeeded the four early issues of the Plain Series in the course of that

year, in which case the helmet symbol may have been added simply to

distinguish the reduced-weight tetradrachms from the visually similar

tetradrachms of Attic weight. But none of the special series carries any such

obvious marker. Thus it may be that the Helmet Series commenced at the very

outset of the reform and was issued alongside the Plain Series, its helmet

symbol perhaps designating it as a specifically military coinage.

47

If this was the

case, the suspension of the Plain Series means that the Alexandria mint actually

reduced its output in 304, by eliminating one series from production.

In the first year of the reform the official ? also supervised the inception of a

third series of reduced-weight tetradrachms, the ( Series. Table 2 shows that

the ( Series and the + Series, each associated with one of the extra die

engravers, initially produced issues ranging in size from modest to exiguous.

Their meagre output is inconsistent with the supposition that extra anvils were

added at the Alexandria mint to process a high volume of coinage. Instead, the

three special series must represent the output of workshops operating apart

from the central mint, yet under its close supervision, and in reasonable

propinquity to one another. The supervision of the Alexandria mint is revealed

by the signatures of Alexandrian officials on coins of the minor workshops:

had already signed Attic-weight tetradrachms (Svonoros 40); z, whose

signature appears on many issues of the ( Series, was arguably the same

individual who signed Zervos Issues II, VI, XIII, and perhaps also Issue XII;

and + had supervised Zervos Issue IX before being given authority over the +

Series of reduced-weight tetradrachms. The propinquity of the minor workshops

to Alexandria and to one another is proved by the collaboration of artists from

different workshops when the activity of the minor workshops peaked.

The minor workshops were probably located outside Alexandria so as to

capture more efficiently the Attic-weight coinage dispersed throughout Egypt.

An obvious site for such a workshop would be the old Greek emporium of

46

Zervos, Delta hoard, pp. 567, with n. 33.

47

Emmons, Overstruck coinage, p. 71 n. 4 reported that visible overstrikes were concentrated in

the Helmet Series; indeed, her list of examples came almost exclusively from the Helmet Series, with

one from the Plain Series, and included almost every issue of the Helmet Series except the very

smallest, as is apparent in Table 2. This evidence of especially careless manufacture initially

suggested the idea of a mobile military mint, but the hypothesis hardly seems tenable in light of the

distribution of Helmet Series tetradrachms, which like other reduced-weight tetradrachms are found

almost exclusively in Egypt. The absence of reported overstrikes in the three minor series may

indicate that their workshops operated under less pressure and had the luxury of preparing their flans

more carefully.

CATHARINE C. LORBER 60

Naucratis. Other candidates include Memphis, Pelusium, or perhaps the Fayum;

but Upper Egypt is excluded by the fact that tetradrachms from all the minor

workshops found their way to Corinth within a very short time of their minting.

The activity of these workshops climaxed in 304, perhaps in connection with

Ptolemys extraordinary measures in support of Rhodes. All the minor

workshops closed very shortly thereafter, perhaps when Demetrius lifted his

siege of Rhodes.

The chronology proposed above for the Helmet Series implies that the revival

of gold coinage should be dated c.298, or perhaps even c.297. So late a date

undercuts the longstanding assumption that Ptolemy introduced his elephant

quadriga gold staters shortly after assuming the diadem, and it would seem to

deny a specific celebratory significance to the coinage itself or to its evocative

types. The inauguration of Ptolemys portrait tetradrachms probably cannot be

dated much later than 294, because Tyre produced a unique tetradrachm of this

type, control linked to the preceding coinage of Demetrius.

48

Newell proposed a

date of 287 for Tyres surrender to Ptolemy and for this tetradrachm issue, but

historians now generally accept that the surrender of Tyre followed Ptolemys

seizure of Cyprus in 295/4.

49

Between the termini 298/7 and 295/4, all Attic-

weight gold staters within Egypt must have been converted into Ptolemaic

elephant quadriga staters. The introduction of an entirely new currency system

c.294 meant that all coinage in silver and gold had to be recoined yet again. By

this time the process was well practiced: F. de Callata has recorded multiple

die links among the first ten emissions of the eagle tetradrachms and estimates

that their production may have required as little as two years.

50

48

E.T. Newell, Tyrus Rediviva (New York, 1923), pl. iii, 9.

49

Newells date was retained in the most recent study of the Tyrian coinage of this period, a

posthumous article by C.A. Hersh, Tyrus Rediviva reconsidered, AJN 10 (1998), pp. 4159. The

chronology seems to be supported by a hoard published in a companion article, C.A. Hersh, The

Phoenicia 1997 hoard of Alexander-type tetradrachms, AJN 10 (1998), pp. 3740. The hoard

contains a long run of Tyrian tetradrachms through the last issue in the name of Alexander and

includes the penultimate die of the series. But the Seleucid issues that close the hoard, which

reportedly showed little or no wear, were SC 42.4, of Carrhae, a mint whose chronology is quite

uncertain; SC 117.1c and 117.1d of Seleucia on the Tigris, now dated c.300; and SC 202.3, 202.5d,

202.8, and 204.1 of Ecbatana, the latest dated c.295. These coins do not justify Hershs burial date of

285280 and seem instead to place the hoards closure c.295, which would be consistent with a date

of 294 for the surrender of Tyre.

50

F. de Callata, Instauration par Ptolme Ster dune conomie montaire ferme, in O. Picard

and J.-Y. Empereur (eds), Lexception gyptienne: production et changes montaires en gypte

hellnistique et romaine, Colloque dAlexandrie, 1315 avril 2002. tudes Alexandrines

(Alexandria, forthcoming).

A REVISED CHRONOLOGY OF THE COINS OF PTOLEMY I 61

APPENDIX

Implications of the New Chronology for Selected Attic-Weight Emissions

If we accept Zervos hypothesis of annual issues, the chronological adjustment

implied by the Demanhur hoard yields new dates for the important milestones

of the Attic-weight coinage. The significance of these milestones may be altered

by their lower dates, but the historical context, regrettably, is not always clear.

The basic chronological framework of the Diadochic period is a matter of

scholarly dispute, owing to the imprecision of Diodorus dating system.

51

Zervos Issue I. The production of precious metal coinage in Egypt apparently

began c.323 rather than c.326. It is tempting to credit the initiative to Ptolemy,

who took up his satrapy in the latter half of 323. The small output recorded by

Zervos (seven tetradrachms from one obverse die)

52

may be consistent with

production commencing near the end of the Macedonian year. In any case, little

or no precious metal coinage can be attributed to Cleomenes of Naucratis, the

acting governor (or perhaps satrap) of Egypt under Alexander.

53

The date at which the Egyptian mint opened is relevant to the question of its

site. M.J. Price submitted that it was originally located at Memphis, which had

earlier served as the mint of Egypts imitative owls, and that minting

operations were later moved to Alexandria.

54

Le Rider defended the traditional

attibution to Alexandria, arguing that construction of the city was essentially

completed during the tenure of Cleomenes, that he probably had more to do in

Alexandria than in Memphis, and that it would have been unnecessary and

inconvenient to locate the mint away from Alexandria.

55

But if the coinage was

inaugurated by Ptolemy, his initial residence in Memphis would make it highly

likely that the mint was located there as well. According to the Satrap Stele, a

hieroglyphic monument dated 311, Ptolemy transferred the seat of his

government from Memphis to Alexandria before the Syrian campaign.

56

This

information is unfortunately ambiguous. Ptolemy annexed the Syro-Phoenician

province for the first time after the conference at Triparadeisus (dated 321 on

51

The traditional high chronology is still advocated, most notably, by A.B. Bosworth, Philip III

Arrhidaeus and the chronology of the Successors, Chiron 22 (1992), pp. 5581; and id., The Legacy

of Alexander (Oxford, 2002). Perhaps the most influential advocate of a lower chronology has been

R.M. Errington, From Babylon to Triparadeisos, JHS 90 (1970), pp. 4977, and Diodorus Siculus

and the chronology of the early Diadochi, 320311 B.C., Hermes 105 (1977), pp. 478504.

52

Zervos, Early tetradrachms of Ptolemy I, p. 11.

53

Arr. 3.5.4; Just. 13.4.11; Arist. Econ. 2.33a; Paus. 1.6.3; Dexippos FGrHist 100 F 8 2. Le Rider,

Clomne, pp. 725, discussed the contradictory evidence of the ancient sources and concluded

that Cleomenes, though the most powerful figure in Egypt from 331 to 323, was probably not

officially its satrap.

54

Price, Alexander, p. 496.

55

Le Rider, Clomne, pp. 889.

56

Satrap Stele l. 4 (K. Sethe, Hieroglyphische Urkunden der griechisch-rmischen Zeit (Leipzig,

19041916), 14, 1216).

CATHARINE C. LORBER 62

the so-called high chronology and to 320 on the low); the invasion itself is dated

either to 320 (mid-summer to the end of September) or to 319.

57

Ptolemy lost

the province to Antigonus in 315 and reoccupied it in 312/11.

58

Accordingly,

there are two possible occasions for the transfer of the capital from Memphis to

Alexandria, preceding either the first or the second Syrian campaign.

59

Zervos Issue V saw the introduction of a series of tetradrachms with a new

obverse type, the head of the deified Alexander in an elephant headdress. These

tetradrachms shared the Zeus reverse of the regular Alexandrine tetradrachms,

were initially issued alongside them, and probably ultimately replaced them. It

is tempting to connect the new iconography with Ptolemys coup in taking

possession of Alexanders remains.

60

Zervos date of issue (322) was perhaps

barely consistent with this interpretation, but only on the high chronology for

the Diadochic period. A reduction in the date of Issue V from 322 to c.319

(Macedonian year 320/19) is implied by the Demanhur hoard, even if Zervos

issues were not actually annual. This makes the introduction of the new coin

type clearly later than Ptolemys diversion of Alexanders funeral cortge, even

on the low chronology, which dates the pious kidnapping to summer or autumn

of 321.

61

The revised date for Issue V also allows other possible interpretations,

though they are not particularly persuasive or satisfying. Emmons advanced the

idea that the portrait of the deified Alexander might be associated with

Ptolemys first annexation of Syria and Phoenicia.

62

The new iconography

might also commemorate the transfer of the capital from Memphis to

Alexandria, assuming it had occurred before the first Syrian campaign.

Zervos Issue XIII introduced the Athena Alkidemos reverse type for

tetradrachms. These tetradrachms were accompanied by drachms and by other

silver fractions never previously struck by Ptolemy, specifically hemidrachms

and diobols, all with the Athena Alkidemos reverse type.

63

If Zervos issues

were truly annual, the new chronology would reduce the date of Issue XIII from

57

Diod. 18.43; App. Syr. 52; Marmor Parium FGrHist 239 B 12. On the Julian date, see P.V.

Wheatley, Ptolemy Soters annexation of Syria, 320 B.C., CQ 45 (1995), pp. 43340.

58

Conquest by Antigonus: Diod. 19.58. Second occupation: Diod. 19.8085. Ptolemys loss of the

province now appears to be securely dated to 315 by Aramaic ostraka: see P.V. Wheatley, The year

22 tetradrachms of Sidon and the date of the battle of Gaza, ZPE 144 (2003), p. 274 with n. 29.

59

Before the first Syrian campaign (320/19): P.M. Fraser, Ptolemaic Alexandria (Oxford, 1972),

vol. 1, p. 7, vol. 2, p. 12 n.28; W. Swinnen, Sur la politique religieuse de Ptolme Ier, in Les

syncrtismes dans les religions grecque et romaine (Paris, 1973), p. 116 n. 2 and p. 120. Before the

second Syrian campaign (313): CAH, vol. 7, part 1, p. 127 [Turner].

60

Among those suggesting a connection: Mrkholm, Early Hellenistic Coinage, p. 63; R.A.

Hazzard, Ptolemaic Coins: An Introduction for Collectors (Toronto, 1995), p. 72.

61

Errington, From Babylon to Triparadeisos, pp. 6465 (321); P. Green, Alexander to Actium:

the Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age (Berkeley/Los Angeles, 1993), p. 13 (late summer

321); G. Hlbl, A History of the Ptolemaic Empire, English trans. by T. Saavedra (London/New

York, 2001), p. 15; Hu, gypten in hellenistischer Zeit, p. 109 (summer or autumn 321).

62

Emmons, Overstruck coinage of Ptolemy I, pp. 734.

63

Hemidrachm: Svoronos 35, pl. ii, 15. Diobol: H. Gitler and C. Lorber, Small silver coins of

Ptolemy I, Studies in Memory of Leo Mildenberg, INJ 14 (200002), no. 1, pl. 6.

A REVISED CHRONOLOGY OF THE COINS OF PTOLEMY I 63

314 to c.311 (Macedonian year 312/11), making this the first emission that

could be attributed to Alexandria with complete confidence. The previous years

coinage had also seen changes, including the redesign of Alexanders head and,

probably, the introduction of the first Alexander/eagle bronzes.

64

A thorough

overhaul of the coinage over the two years 313/12 and 312/11 may have been

undertaken in connection with the relocation of the capital and the mint; the

result, in any case, was a new national coinage that paid explicit tribute to

Alexander and to the Macedonian origin of Ptolemy and many of his Friends

(courtiers) and troops.

Zervos Issue XIII is also noteworthy for the exceptional coin legend

AAEEANAPEION HTOAEMAIOY which appears on some of its

tetradrachms.

65

Mrkholm argued that the word AAEEANAPEION probably

designated the mint city, and Price concurred, reasoning that the legend might

mark the opening of a mint at Alexandria.

66

This reading of the coin legend has

been rejected by many scholars.

67

The nearly parallel formulation

KYPANION HTOAEMAIO (Cyrenian coin of Ptolemy), which appears

on gold staters and hemistaters of Cyrene, suggests that

AAEEANAPEION HTOAEMAIOY should be translated as Ptolemys

Alexander-coin, with the adjective perhaps referring to the image of Alexander

on the obverse.

The appearance of Ptolemys name on coins struck during his satrapy is

consistent with the practice of Persian satraps, including some who served

under Alexander. However it is a form of self-promotion not attempted by the

other Successors. Ptolemy may (or may not) have been signaling aspirations to

kingship, but the swift disappearance of such legends suggests they were

perceived by their intended audience as unacceptably ambitious. In either case

this sort of propaganda would have been strangely maladroit in 314, after

Antigonus had deprived Ptolemy of his Syro-Phoenician province and meddled

in Ptolemaic Cyprus. The proposed new date of 312/11 puts the exploratory

coin legend in a more plausible historical context, following a string of recent

achievements in the field of foreign policy: the suppression of the Cyrenian

revolt,

68

the annexation of Cyprus,

69

and the victory at Gaza in autumn 312,

64

Svoronos 30A, Svoronos 31, and SNG Copenhagen 32.

65

Svoronos 32.

66

Mrkholm, Cyrene and Ptolemy I, p. 149; Price, Alexander, p. 496.

67

D. Knoepfler, Ttradrachmes attiques et argent alexandrin chez Diogne Laerce, Mus.

Helveticum 46 (1989), pp. 20510; O. Masson, RN 1991, pp. 6971; G. Le Rider, review of Price,

Alexander in SNR 71 (1992), p. 225; Hazzard, Ptolemaic Coins, pp. 723; Le Rider, Clomne, p.

88.

68

Diod. 19.79.1. Ptolemys suppression of the Cyrenean revolt was dated to summer 313 by P.V.

Wheatley, The chronology of the Third Diadoch War, 315311 B.C., Phoenix 52 (1998), pp. 2678

with n. 58, and to summer 312 by Errington, Diodorus Siculus and the chronology of the early

Diadochoi, p. 499.

CATHARINE C. LORBER 64

which permitted Ptolemy to reoccupy Coele Syria and Phoenicia.

70

In this

context, the legend not only labelled the redesigned coinage as Ptolemys own

but set up the Athena Alkidemos reverse type as a symbol for his martial spirit

and his success at arms.

A lower date for the Alexandrian issue has implications for the numismatic

chronology of Cyrene. Basing himself on parallels with Ptolemys Egyptian

coinage, Mrkholm proposed a date of c.315 for an unusual Cyrenian silver

didrachm with the Athena Alkidemos reverse, and a date of c.314 for the series

of gold staters and hemistaters with the legend KYPANION HTOAEMAIO.

71

Mrkholm could offer no explanation for Ptolemys symbolic intrusions on the

coinage of Cyrene at this period, but his numismatic chronology led G. Hlbl to

deduce that an assertion of political supremacy by Ptolemy may have instigated

the Cyrenian revolt in 313.

72

With the Athena Alkidemos reverse type and the

legend AAEEANAPEION HTOAEMAIOY both downdated to c.311, the

Cyrenian coins naming Ptolemy or employing his new reverse type can now be

placed after the suppression of the revolt, in which context they make sense.

The new Alexandrian coin types of c.311 were also promptly employed on a

celebrated emission of tetradrachms minted at Sidon in 312/11 and dated

according to the local era, and on an emission of obols from an uncertain mint

in Palestine, which must belong to the same year.

73

The Sidonian tetradrachms

in fact serve as a check on our revised chronology for Ptolemys Egyptian

coinage. They show that Issue XIII cannot be dated later than 312/11, so the

reduction of Zervos dates implied by the Demanhur hoard must therefore be by

three years, not four.

69

Diod. 19.79.46. The annexation of Cyprus was dated to 313 or 312 by Wheatley, Chronology

of the Third Diadoch War, pp. 2678 with n.58, and to 312 by Errington, Diodorus Siculus and the

chronology of the early Diadochoi, p. 499.

70

The date of the battle seems firmly fixed by the numismatic evidence: see Wheatley, The year

22 tetradrachms of Sidon, pp. 2725.

71

Mrkholm, Cyrene and Ptolemy I, pp. 1489.

72

Hlbl, History of the Ptolemaic Empire, p. 18. A date of 313 for the Cyrenean revolt is also

accepted by an advocate of the high chronology: see Wheatley, Chronology of the Third Diadoch

War, pp. 2678 (with n.58) and 279.

73

The first such tetradrachm was published by Brett, Aphlaston, TINC, p. 23; for an illustration,

see Mrkholm, Early Hellenistic Coinage, pl. vi, 94; for corpus and die information, see Wheatley,

The year 22 tetradrachms of Sidon, pp. 26872. Obols: Gitler and Lorber, Small silver coins of

Ptolemy I, no. 3.

Вам также может понравиться

- Power Systems Analysis 2/E Arthur R. Bergen, Vijay Vittal Solutions ManualДокумент5 страницPower Systems Analysis 2/E Arthur R. Bergen, Vijay Vittal Solutions ManualAsuna0% (4)

- Baldwin LampsakosДокумент92 страницыBaldwin LampsakosJon GressОценок пока нет

- 2015 Olbrycht DiademДокумент13 страниц2015 Olbrycht DiademMarkus OlОценок пока нет

- The Dated Alexander Coinage of Sidon and Ake (1916)Документ124 страницыThe Dated Alexander Coinage of Sidon and Ake (1916)Georgian IonОценок пока нет

- ACT 1, SCENE 7: Macbeth's CastleДокумент3 страницыACT 1, SCENE 7: Macbeth's CastleViranthi CoorayОценок пока нет

- The Origins and Evolution of Coinage in Belgic Gaul / Simone ScheersДокумент5 страницThe Origins and Evolution of Coinage in Belgic Gaul / Simone ScheersDigital Library Numis (DLN)Оценок пока нет

- Greek Coins Acquired by The British Museum in 1890 / by Warwick WrothДокумент21 страницаGreek Coins Acquired by The British Museum in 1890 / by Warwick WrothDigital Library Numis (DLN)Оценок пока нет

- Some Hoards and Stray Finds From The Latin East / D.M. MetcalfДокумент27 страницSome Hoards and Stray Finds From The Latin East / D.M. MetcalfDigital Library Numis (DLN)100% (1)

- A New Cleopatra Tetradrachm of Ascalon / Agnes Baldwin BrettДокумент13 страницA New Cleopatra Tetradrachm of Ascalon / Agnes Baldwin BrettDigital Library Numis (DLN)100% (1)

- Catalogue of Greek Coins - The Ptolemies, Kings of EgyptОт EverandCatalogue of Greek Coins - The Ptolemies, Kings of EgyptОценок пока нет

- The ST Nicholas or 'Boy Bishop' Tokens / by S.E. RigoldДокумент25 страницThe ST Nicholas or 'Boy Bishop' Tokens / by S.E. RigoldDigital Library Numis (DLN)Оценок пока нет

- Greek Coins Acquired by The British Museum in 1921 / (G.F. Hill)Документ33 страницыGreek Coins Acquired by The British Museum in 1921 / (G.F. Hill)Digital Library Numis (DLN)Оценок пока нет

- Mattingly, Roman CoinsДокумент4 страницыMattingly, Roman CoinsIonutz IonutzОценок пока нет

- Gulbenkian Greek Coins. Gift by Mr. C. S. GulbenkianДокумент4 страницыGulbenkian Greek Coins. Gift by Mr. C. S. GulbenkianHesham ElshazlyОценок пока нет

- A Seleucid Coin From KarurДокумент5 страницA Seleucid Coin From KarurJee Francis TherattilОценок пока нет

- Greek Coins Acquired by The British Museum in 1922 / (G.F. Hill)Документ37 страницGreek Coins Acquired by The British Museum in 1922 / (G.F. Hill)Digital Library Numis (DLN)Оценок пока нет

- Two - Medallions Valerian Holmes 2005Документ4 страницыTwo - Medallions Valerian Holmes 2005Davor MargeticОценок пока нет

- Henry I Type 14 / Martin AllenДокумент114 страницHenry I Type 14 / Martin AllenDigital Library Numis (DLN)Оценок пока нет

- The Medals Concerning John Law and The Mississippi System / John W. AdamsДокумент96 страницThe Medals Concerning John Law and The Mississippi System / John W. AdamsDigital Library Numis (DLN)Оценок пока нет

- Ptolemaic Coinage Reference by Svoronos Translated to EnglishДокумент397 страницPtolemaic Coinage Reference by Svoronos Translated to EnglishCassivelanОценок пока нет

- The Date of The Sutton Hoo Coins / Alan M. Stahl and W.A. OddyДокумент19 страницThe Date of The Sutton Hoo Coins / Alan M. Stahl and W.A. OddyDigital Library Numis (DLN)Оценок пока нет

- Barclay Vincent HeadДокумент9 страницBarclay Vincent HeadDigital Library Numis (DLN)Оценок пока нет

- A Revised Survey of The Seventeenth-Century Tokens of Buckinghamshire / George Berry and Peter MorleyДокумент33 страницыA Revised Survey of The Seventeenth-Century Tokens of Buckinghamshire / George Berry and Peter MorleyDigital Library Numis (DLN)Оценок пока нет

- The-Celator-Vol.26-No.05-May-Jun 2012 PDFДокумент60 страницThe-Celator-Vol.26-No.05-May-Jun 2012 PDF12chainsОценок пока нет

- The Two Primary Series of Sceattas / by S.E. RigoldДокумент53 страницыThe Two Primary Series of Sceattas / by S.E. RigoldDigital Library Numis (DLN)Оценок пока нет

- Newnumismatic 19 RoyauoftДокумент370 страницNewnumismatic 19 RoyauoftChristopher Dixon100% (1)

- 09 BALDWINS 2016 Summer FIXED PRICE LIST - 07 - IRISH COINS PDFДокумент22 страницы09 BALDWINS 2016 Summer FIXED PRICE LIST - 07 - IRISH COINS PDFDer AdlerОценок пока нет

- Rare and Unedited Sicilian Coins / (L. de Hirsch de Gerenth)Документ9 страницRare and Unedited Sicilian Coins / (L. de Hirsch de Gerenth)Digital Library Numis (DLN)Оценок пока нет

- Anglo-Saxon Acquisitions of The British Museum. II: Kent Archbishops of Canterbury East Anglia / (G. C. Brooke)Документ21 страницаAnglo-Saxon Acquisitions of The British Museum. II: Kent Archbishops of Canterbury East Anglia / (G. C. Brooke)Digital Library Numis (DLN)Оценок пока нет

- A New Sceat of The Dorestat/Madelinus-type / by Arent PolДокумент4 страницыA New Sceat of The Dorestat/Madelinus-type / by Arent PolDigital Library Numis (DLN)Оценок пока нет

- Metrological Notes On The Ancient Electrum Coins Struck Between The Lelantian Wars and The Accession of Darius / (Barclay V. Head)Документ65 страницMetrological Notes On The Ancient Electrum Coins Struck Between The Lelantian Wars and The Accession of Darius / (Barclay V. Head)Digital Library Numis (DLN)Оценок пока нет

- A Provisional List of Dutch Lion-Dollars / (H. Enno Van Gelder)Документ25 страницA Provisional List of Dutch Lion-Dollars / (H. Enno Van Gelder)Digital Library Numis (DLN)100% (2)

- The Coinage of Offa Revisited / Rory NaismithДокумент37 страницThe Coinage of Offa Revisited / Rory NaismithDigital Library Numis (DLN)Оценок пока нет

- Review of Histoire de Bérytos et d’Hélipolis d’après leurs monnaiesДокумент8 страницReview of Histoire de Bérytos et d’Hélipolis d’après leurs monnaiesZiad SawayaОценок пока нет

- The British Numismatic Society: A History / Hugh PaganДокумент73 страницыThe British Numismatic Society: A History / Hugh PaganDigital Library Numis (DLN)Оценок пока нет

- The Coinage of Roman AlexandriaДокумент2 страницыThe Coinage of Roman AlexandriaResackОценок пока нет

- Byzantine Miliaresion and Arab Dirhem: Some Notes On Their Relationship / (George C. Miles)Документ37 страницByzantine Miliaresion and Arab Dirhem: Some Notes On Their Relationship / (George C. Miles)Digital Library Numis (DLN)100% (1)

- ERIC Section7 Diocletian - Constantius II 497Документ112 страницERIC Section7 Diocletian - Constantius II 497Darko SekulicОценок пока нет

- Greek Coinages of Palestine: Oren TalДокумент23 страницыGreek Coinages of Palestine: Oren TalDelvon Taylor100% (1)

- Coin-Types of Some Kilikian Cities / (F. Imhoof-Blumer)Документ27 страницCoin-Types of Some Kilikian Cities / (F. Imhoof-Blumer)Digital Library Numis (DLN)Оценок пока нет

- The Pattern Halfpennies and Farthings of Anne / by C. Wilson PeckДокумент23 страницыThe Pattern Halfpennies and Farthings of Anne / by C. Wilson PeckDigital Library Numis (DLN)100% (1)

- 'Barbarous Radiates': Imitations of Third-Century Roman Coins / by Philip V. HillДокумент64 страницы'Barbarous Radiates': Imitations of Third-Century Roman Coins / by Philip V. HillDigital Library Numis (DLN)100% (1)

- Greek Coins Acquired by The British Museum in 1892Документ23 страницыGreek Coins Acquired by The British Museum in 1892Digital Library Numis (DLN)Оценок пока нет

- The Coinage of Amorgos: Aigiale, Arkesine, Minoa and The Koinon of The Amorgians / Katerini LiampiДокумент61 страницаThe Coinage of Amorgos: Aigiale, Arkesine, Minoa and The Koinon of The Amorgians / Katerini LiampiDigital Library Numis (DLN)Оценок пока нет

- The 'Standard' and 'London' Series of Anglo-Saxon Sceattas / by Philip V. HillДокумент37 страницThe 'Standard' and 'London' Series of Anglo-Saxon Sceattas / by Philip V. HillDigital Library Numis (DLN)Оценок пока нет

- Asia Minor in The Archaic and Classical Periods / Koray KonukДокумент24 страницыAsia Minor in The Archaic and Classical Periods / Koray KonukDigital Library Numis (DLN)Оценок пока нет

- 03 BALDWINS 2016 Summer FIXED PRICE LIST - 01 - ANCIENT COINS PDFДокумент48 страниц03 BALDWINS 2016 Summer FIXED PRICE LIST - 01 - ANCIENT COINS PDFDer AdlerОценок пока нет

- Greek Coins Acquired by The British Museum in 1889 / (Warwick Wroth)Документ23 страницыGreek Coins Acquired by The British Museum in 1889 / (Warwick Wroth)Digital Library Numis (DLN)Оценок пока нет

- White Gold Revealing The World's Earliest CoinsДокумент6 страницWhite Gold Revealing The World's Earliest CoinsАлександар ТомићОценок пока нет

- Two Roman Hoards of Coins From Egypt / by J.G. MilneДокумент16 страницTwo Roman Hoards of Coins From Egypt / by J.G. MilneDigital Library Numis (DLN)Оценок пока нет

- Greek Coins Acquired by The British Museum, 1914-1916 / (G.F. Hill)Документ37 страницGreek Coins Acquired by The British Museum, 1914-1916 / (G.F. Hill)Digital Library Numis (DLN)Оценок пока нет

- With Particular Reference To The Mints of Chichester, London, Dover, and Northampton and The Moneyer(s) Cynsige or KinseyДокумент45 страницWith Particular Reference To The Mints of Chichester, London, Dover, and Northampton and The Moneyer(s) Cynsige or KinseyDigital Library Numis (DLN)Оценок пока нет

- A Hoard of Byzantine Folles From Beirut / Paul BeliënДокумент9 страницA Hoard of Byzantine Folles From Beirut / Paul BeliënDigital Library Numis (DLN)Оценок пока нет

- The-Celator-Vol. 01-No. 01-Feb-Mar 1987 PDFДокумент12 страницThe-Celator-Vol. 01-No. 01-Feb-Mar 1987 PDF12chainsОценок пока нет

- Osservazioni Sui Rinvenimenti Monetari Dagli Scavi Archeologici Dell'antica Caulonia / Giorgia GarganoДокумент32 страницыOsservazioni Sui Rinvenimenti Monetari Dagli Scavi Archeologici Dell'antica Caulonia / Giorgia GarganoDigital Library Numis (DLN)Оценок пока нет

- Greek Coins Acquired by The British Museum in 1920 / (G.F. Hill)Документ23 страницыGreek Coins Acquired by The British Museum in 1920 / (G.F. Hill)Digital Library Numis (DLN)Оценок пока нет

- Touratsoglou, Coin Production and Circulation in Roman Peloponesus PDFДокумент23 страницыTouratsoglou, Coin Production and Circulation in Roman Peloponesus PDFCromwellОценок пока нет

- Pausaniaa NumismaticДокумент242 страницыPausaniaa NumismaticvastamОценок пока нет

- Baldwin39s Islamic Coin Auction 22pdfДокумент64 страницыBaldwin39s Islamic Coin Auction 22pdfbelfkihОценок пока нет

- Geografic Coin FindsДокумент12 страницGeografic Coin Findsemocy91Оценок пока нет

- A Hoard of Coins From Eastern Parthia / by Heidemarie KochДокумент99 страницA Hoard of Coins From Eastern Parthia / by Heidemarie KochDigital Library Numis (DLN)Оценок пока нет

- Butrint 6: Excavations on the Vrina Plain: Volume 2 - The FindsОт EverandButrint 6: Excavations on the Vrina Plain: Volume 2 - The FindsОценок пока нет

- Greek Mouldings of Kos and RhodesДокумент34 страницыGreek Mouldings of Kos and Rhodesمجدى محمود طلبهОценок пока нет

- Petra PDFДокумент11 страницPetra PDFمجدى محمود طلبهОценок пока нет

- The Egyptian Egyptologists Publications of Dendera Temple Texts Ayman Wahby TaherДокумент1 страницаThe Egyptian Egyptologists Publications of Dendera Temple Texts Ayman Wahby Taherمجدى محمود طلبهОценок пока нет

- Forms and Decoration of Graeco-Roman HouДокумент35 страницForms and Decoration of Graeco-Roman Houمجدى محمود طلبهОценок пока нет

- Petra PDFДокумент11 страницPetra PDFمجدى محمود طلبهОценок пока нет

- Forms and Decoration of Graeco-Roman HouДокумент35 страницForms and Decoration of Graeco-Roman Houمجدى محمود طلبهОценок пока нет

- Forms and Decoration of Graeco-Roman HouДокумент35 страницForms and Decoration of Graeco-Roman Houمجدى محمود طلبهОценок пока нет

- 08 Hellenistic PDFДокумент121 страница08 Hellenistic PDFمجدى محمود طلبه100% (1)

- Roman ArchitectureДокумент28 страницRoman Architectureمجدى محمود طلبهОценок пока нет

- 6449 8874 1 PB PDFДокумент7 страниц6449 8874 1 PB PDFمجدى محمود طلبهОценок пока нет

- Presentacion .1: Additional Career ..4Документ10 страницPresentacion .1: Additional Career ..4Leydi Patricia CuevaОценок пока нет

- 848 Goniothalamus Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical ReviewДокумент15 страниц848 Goniothalamus Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical ReviewYuniar Ayu SuweleОценок пока нет

- Crre Wise SRKRДокумент20 страницCrre Wise SRKRKrishna MurthyОценок пока нет

- Date de NastereДокумент17 страницDate de NastereElla JebeleanОценок пока нет

- Shakespeare Lifetimes Introduction Powerpoint PresentationДокумент46 страницShakespeare Lifetimes Introduction Powerpoint PresentationMichiko Del GiudiceОценок пока нет

- Paul Henri de Leeuw (Born 26 March 1962) Is A Dutch TelevisionДокумент4 страницыPaul Henri de Leeuw (Born 26 March 1962) Is A Dutch TelevisionlimentuОценок пока нет

- Women WarriorsДокумент16 страницWomen WarriorsMonika TodorovaОценок пока нет

- Event 14420 01-03-2023 PDFДокумент19 страницEvent 14420 01-03-2023 PDFSunita VimalОценок пока нет

- History GK Special Vidroh - : Most Expected Ques + PyqsДокумент20 страницHistory GK Special Vidroh - : Most Expected Ques + PyqsSaurabh MehtaОценок пока нет

- The Search For Knowledge Among SDA, MadagascarДокумент321 страницаThe Search For Knowledge Among SDA, MadagascartomОценок пока нет

- Bung Karno and The Fossilization of Soekarno's ThoughtДокумент20 страницBung Karno and The Fossilization of Soekarno's ThoughtRaihan JustinОценок пока нет

- DeterminationДокумент17 страницDeterminationUCHOOSE2861Оценок пока нет

- Iron Man All ComicsДокумент3 страницыIron Man All ComicsVicky StarkОценок пока нет

- Mughals Vijayanagara Kings Bahamani Kings Marathas Rule in IndiaДокумент3 страницыMughals Vijayanagara Kings Bahamani Kings Marathas Rule in IndiaNilesh KhadseОценок пока нет

- Jazz Assignment 3Документ3 страницыJazz Assignment 3Diana FoxОценок пока нет

- Wilkinson (2012) Aurelius Gaius (AE 1981.777) and Imperial Journeys, 293-299Документ7 страницWilkinson (2012) Aurelius Gaius (AE 1981.777) and Imperial Journeys, 293-299Juan Pablo Prieto IommiОценок пока нет

- Animal Welfare Board of IndiaДокумент10 страницAnimal Welfare Board of IndiaPranayShirwadkarОценок пока нет

- 63 Edp Training CompletedДокумент294 страницы63 Edp Training CompletedAtul GhodakadeОценок пока нет

- Sindh E-Centralized College Admission Policy 2016: Computer Science Placements at Two CollegesДокумент34 страницыSindh E-Centralized College Admission Policy 2016: Computer Science Placements at Two CollegeslubnaОценок пока нет

- 420 618 GoDownMoses PDFДокумент4 страницы420 618 GoDownMoses PDFJenrryGiovanyVenturaDiasОценок пока нет

- Bunkers Hill MAP WREXHAM AREAДокумент1 страницаBunkers Hill MAP WREXHAM AREAAnnette EdwardsОценок пока нет

- Introduction AP History For All Appsc Exam OnlyДокумент8 страницIntroduction AP History For All Appsc Exam OnlyChintha SreenivasuluОценок пока нет

- Saxophonists' SetsДокумент4 страницыSaxophonists' Setsmalanghino100% (1)

- Lista e VepraveДокумент36 страницLista e VepraveMariglenaОценок пока нет

- WHScott Cracks in The Parchment CurtainДокумент217 страницWHScott Cracks in The Parchment CurtainTrisha Mae Marcel CatedralОценок пока нет

- Brief History of BasketballДокумент16 страницBrief History of BasketballPhương LinhОценок пока нет

- Lascano, RizalДокумент3 страницыLascano, Rizal23Lopez, JoanaMarieSTEM AОценок пока нет

- Coe, Michael D. La Victoria PDFДокумент272 страницыCoe, Michael D. La Victoria PDFmiguelОценок пока нет