Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Emperor Vs Ismail Hirji On 4 September, 1929

Загружено:

sreevarsha0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

15 просмотров8 страницjudgement

Оригинальное название

Emperor vs Ismail Hirji on 4 September, 1929

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документjudgement

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

15 просмотров8 страницEmperor Vs Ismail Hirji On 4 September, 1929

Загружено:

sreevarshajudgement

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 8

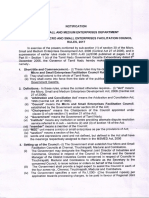

Bombay High Court

Emperor vs Ismail Hirji on 4 September, 1929

Equivalent citations: (1929) 31 BOMLR 1349

Author: Patkar

Bench: Patkar, Wild

JUDGMENT Patkar, J.

1. In this case the Presidency Magistrate, Second Court, Bombay, has made a reference, under

Section 432 of the Criminal Procedure Code, submitting for decision certain points of law arising in

a case pending before him.

2. One Ibrahim Ismail made a complaint on Oath on September 27, 1928, before the Commissioner

of Police, Bombay. Instead of issuing a special warrant under Section 6 of the Bombay Prevention of

Gambling Act, 1887, he personally raided the premises in company with other police-officers. The

Commissioner entered the main entrance and Sub-Inspector Salaskar. entered the side gate and

arrested accused Nos. 2 and 3, Police Constable No. 714 C.T. arrested accused No. 4. R.B. Sabaji

arrested 1929 accused No. 1 and Inspector Achrekar and Havaldar 932-K arrested accused Nos. 5, 6

and 8. Accused No. 7 was arrested by another policeman, Panchnamas were made of the articles

found in the passage and on the person of the accused. Twenty-seven slips were found in the passage

bearing the names of the horses, the amount of bet, win or place, and single or double. The punters

got receipts for the payments made to the bookmakers in the form of printed curt chits with

numbers thereon which were inserted in the slips for identification. Three cart chits were found in

the passage, and four cart chit books were also found in the passages. Currency notes of the value of

Rs. 145 and a moneybag dropped by accused No. 3 were found in the passage.

3. The learned Magistrate instead of making a reference- to this Court ought to have decided the

points involved in this case leaving the parties aggrieved to approach this Court in case they were

dissatisfied with his decision.

4. The first question referred by the learned Magistrate is, whether offences punishable under

Section 4 of the Bombay Prevention of Gambling Act IV of 1887 as modified up to date are

cognizable offences in all cases. In Emperor v. Fernad (1907) 1. L.B. 31 Bom. 438, a. o. 9 Bom L.R.

696. it was held that as a First Class Magistrate has under Section 6 of the Gambling Act IV of 1887

power to give authority, under a special warrant to certain police-officers, to make arrest and search,

the Legislature must be presumed to have intended that the First Class Magistrate should have

authority to make the arrest and the search himself, if necessary, according to the principle of the

legal maxim that "whatever a man sui juris may do of himself, he may do by another," and its

correlative that "what is done by another is to be deemed done by the party himself." In Emperor v.

Jaffur Mahomed (1912) I.L.R. 37 Bom. 402, s.c. 15 Bom. L.R. 106 the learned Judges were not

prepared to base their judgment upon a view of Section 6 contrary to the view taken in Fernad's

case. In Emperor v. Abasbhai (1925) I.L.R. 50 Bom. 344, s.c. 28 Bom. L.R. 272. it was held by

Marten and Madgavkar JJ, following the decision in Queen-Empress v. Deodhar Singh (1899) I.L.R.

27 Cal. 144, that the offences under Sections 4 and 5 were cognisable offences within the meaning of

Emperor vs Ismail Hirji on 4 September, 1929

Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/10988/ 1

Section 4(f) of the Criminal Procedure Code, rather than non-cognizable offences under

Sub-clause(n) of that section. In Emperor v. Chandri (1924) I.L.R. 49 Bom. 212, 221, s.c. 26 Bom.

L.R. 1225, it was held by Fawcett J. that there were serious limitations on the power of arrest under

Section 10 of the Bombay Prevention of Prostitution Act XI of 1923, and that any case where those

conditions are not complied with cannot be described as a cognizable case. Under Section 6 of the

Gambling Act and on the authority of the decision in the case of Emperor v. Fernad the

Commissioner of Police could arrest without a warrant, and the words "a police-officer may arrest"

in Section 4(1)(f) do not mean every or any police-officer, and provided that a superior police-officer

has power to arrest without a warrant, the offence is a cognizable offence. It was further held by

Madgavkar J. in Emperor v. Abasbhai that the report of the police-officer could have been treated in

that case as a complaint. Both the learned Judges came to the conclusion that the Magistrate had

jurisdiction as the offences were cognizable, and that the case fell under Section 190(b) of the

Criminal Procedure Code. The learned Magistrate ought to have followed the clear ruling of this

Court in Emperor v. Abasbhai.

5. It is urged, however, on behalf of the accused that the remarks of Chandavarkar J. in Fernad's

case were obiter, and that, according to the definition of a cognizable offence in Section 4(1)(f) of the

Criminal Procedure Code, the offences under Sections 4 and 5 of the Gambling Act would not be

cognizable offences as a police-officer could not arrest in accordance with the second schedule of the

Criminal Procedure Code or under any law for the time being in force, without a warrant. It is

further urged that in Schedule II, relating to offences under other laws, an offence punishable with

imprisonment for less than one year or with fine only is a non-cognizable offence, and under Section

6 of the Gambling Act no express power is given to the Commissioner of Police to arrest or to make

the search himself as is conferred by Section 6 of the Bengal Public Gambling Act II of 1867, and

that the case of Queen-Empress v. Deodhar Singh, followed in Emperor Abasbhai, is based on

Section 5 of the Bengal Act. Section 6 of the Gambling Act is correctly interpreted by the decisions

referred to above which are no less binding on us than on the Magistrate. The words "under any law

for the time being in force" in Section 4(f), Criminal Procedure Code, are, however, in my opinion,

wide enough to include an express or implied provision of any law or enactment and would cover

the application of the maxims qui facit per alium facit per se (whatever a man may do of himself, he

may do by another) and qui per alium facit per seipsum facere videtur (he who does an act through

another is deemed in law to do it himself) to any provision of any enactment, in order to arrive at the

true intention of the enactment. Though the Act was amended several times' since the decision in

Fernad's case, the Legislature has not expressed its true intention to be otherwise than that

determined by judicial decisions. It is to be presumed that there is no intention to prevent the

application of such maxims unless there is something in the language or in the object of the statute

to the contrary. See Maxwell on the Interpretation of Statutes, 6th Edition, page 134.

6. The second question is, whether the arrests are illegal. It is contended that the arrests are illegal

on the following grounds: (1) that there was no complaint on oath, (2) that the passage is not "a

place" within the meaning of Section 6 of the Gambling Act, (8) that the Commissioner did not

satisfy himself that there were good grounds for the suspicion, and (4) that the Commissioner could

not authorise the constables to arrest, and the arrests by Sub-Inspector Salaskar were not in the

actual presence of the Commissioner.

Emperor vs Ismail Hirji on 4 September, 1929

Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/10988/ 2

7. The first point arising for decision is, whether Exhibit A is a legal complaint on oath before the

Commissioner of Police. According to the decision in Emperor v. Tribhovan Motiram (1928) 31

Bom. L.R. 53, 56, 60, the Commissioner of Police was competent to administer an oath to Ibrahim

Ismail under Section 6 of the Gambling Act. It is urged, however, that though the word "complaint"

in Section 6 is not to be understood in a technical sense, Ibrahim who made the complaint to secure

a reward cannot be considered to be a person who had any grievance, and therefore was not

competent to make a complaint Section 6 does not impose any limitation on the power of any

person to make a complaint on oath to the Commissioner of Police. In In re Ganesh Narayan Sathe

(1889) I.L.R. 13 Bom. 600 it was held that as a general rule any person, having knowledge of the

commission of an offence, may set the law in motion by a complaint, even though he is not

personally interested or affected by the offence. The objection, therefore, raised on this point on

behalf of the accused is, in my opinion, without substance.

8. The second question arising for decision is, whether the passage is a "place" within the meaning

of Section 6 of the Gambling Act. In Emperor v. Jusub Allyi (1905) I.L.R. 29 Bom. 386, 391, s.c. 7

Bom. L.R. 333 it was held by Batty J. that the machwa must be considered to have been a place

within the meaning of Section 4 rather than of Section 12, being more of the nature of a house or

room than of a place ejusdem generis with a street or thoroughfare. In Emperor v. Fattoo Mahomed

(1913) I.L.R. 37 Bom. 651, s.c. 15 Bom. L.R. 689, a small open space surrounded by houses on all

sides and accessible only by a narrow lane was held to be a place within the meaning of Section 4 of

the Gambling Act as being appropriated for the business of betting. There appears to be no conflict

in the decisions in Jusub Ally's case and Faitoo Mahomed's case to justify a reference on this point.

In Powell v. Kempton Park Racecourse Company (1899) A.C. 143 Lord James of Hereford held (p.

194) :

Speaking in general terms, whilst the place mentioned in the Act must be to some extent ejusdem

generis with house, room, or office, I do not thick that it need possess the same characteristics; for

instance, it need not be covered in or roofed. It may be, to some extent, an open space. But certain

conditions must exist in order to bring such space within the word 'place'. There must be a defined

area so marked out that it can be found and recognised as 'the place' where the business is carried

on and wherein the bettor can be found.

9. In Eastwood v. Miller (1874) L.R. 9 Q.B. 440. it was held that an enclosed area, though uncovered,

might as well be "a place" within the Act as a place either covered with canvas as a tent or a light

structure as a building. It is a question of fact in each case whether the business of betting is

localized so that people may fairly resort to the place where it is carried on. I may also refer in this

connection to the case of Brown v. Patch (1899) 1 Q.B. 892. It would be for the Magistrate to

consider on the evidence whether the passages are "a place" within the meaning of the Act. Having

regard to the decision in Emperor v. Fattoo Mahomed (1913) I.L.R. 37 Bom. 651, s.c. 15 Bom. L.R.

689, there appears to be no ground for any doubt justifying a reference on this point by the

Magistrate.

10. The third point is, whether the Commissioner satisfied himself that there were good grounds for

the suspicion that any place is used as a common gaming house. It is a question of fact which the

Emperor vs Ismail Hirji on 4 September, 1929

Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/10988/ 3

Magistrate has to decide on the evidence in the case and is not a question of law which should have

been referred by him to this Court.

11. The fourth point is, whether the arrests by the constables or by Sub-Inspector Salaskar are illegal.

Under Section 6 of the Gambling Act, the Commissioner of Police has the power to give authority, by

special warrant under his hand, to any Inspector, or other superior officer of Police, of not lees rank

than a Sub-Inspector.

12. (a) to enter, "with the assistance of such persons as may be 1920 found necessary, by night or by

day, and by force, if necessary, any such house, room or place, and

13. (b) to take into custody and bring before a Magistrate all persons whom he finds therein,

whether they are then actually gaming or not.

14. According to the authorities to which I have already referred the Commissioner of Police had the

power to enter with the assistance of such persona as may be found necessary and to arrest the

persons whom he found therein. It is not possible for the Commissioner of Police alone, if he

intended to raid the premises, to arrest a multitude of persons. It is, therefore, provided by the

Legislature that he may enter with the assistance of such persons as may be found necessary. Mr.

Salaskar in his evidence says that he was instructed to raid the premises with his men by the rear

gate simultaneously with the raid from the main gate by the Commissioner of Police. The arrests,

therefore, by Salaskar were under the express authority of the Commissioner of Police and in the

presence of the Commissioner though not within his view. I think that the arrests by Mr. Salaskar

were not illegal It is not contended before us that arrests by any other police-officer were illegal. The

point loses any importance in this case as the offences are cognizable and the Magistrate has

jurisdiction to investigate the case under Section 190, Clause (b). It is not, therefore, necessary to go

into the question urged by the learned Government Pleader that even on the assumption that the

offences were not cognizable the Magistrate had jurisdiction to treat the report by the police-officer

as a complaint under Section 190, Clause (a), according to the view of Madgavkar J, in Emperor v.

Abasbhai (1915) I.L.R. 80 Bom. 344, s.c. 28 Bom. L.R. 272. and the decision in Emperor v.

Shivaswami (1927) 29 Bom. L.B. 742.

15. The last question is, whether there was any gaming at all when the meeting was postponed. It

appears from Exhibit T that the race which was to be run on September 9 was postponed to October

6. It is urged on behalf of the accused that in a wager both the parties must contemplate the

determination of the future uncertain event as the sole condition of their contract, and as in the

present case the future uncertain event did not happen, there was no wager, and reliance is placed

on Anson on Contract;, pages 230 and 231, and the case of Ellesmere (Earl) v. Wallace (1929) 2 Ch.

1, 26. In the present case, the charge against the accused was under Clause 4 (a) and 4 (c) and not

under Section 5 of the Gambling Act. The question, therefore, does not really arise in the present

case. In Halsbury's Laws of England, Vol. XV, page 267, para. 649, it is stated as follows :

A wagering contract has been described as one by which two persons, professing to hold opposite

views touching the issue of a future uncertain event, mutually agree that, dependent upon the

Emperor vs Ismail Hirji on 4 September, 1929

Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/10988/ 4

determination of such event, one shall win from the other, and that other shall pay or hand over to

him, a sum of money or other stake; neither of the contracting parties having any other interest in

that contract than the sum or stake which he will so win or lose, there being no other real

consideration for the making of such contract by either of the parties.

16. A bet is defined in Thacker v. Hardy (1878) 4 Q.B.D. 685. and Carlill v. Carbolic Smoke Ball

Company (1892) 2 Q.B. 484, 490. A bet need not be as regards the issue of a future uncertain event

and may be upon a past event, e. g., whether a particular horse won a race in a certain year. In such

a case the bet is upon the accuracy of the information, belief or memory of the parties and the event

is the proof that one or the other was accurate, A person may bet against what he believes the issue

will be, e. g., a man may bet against a horse which he believes will win in order to secure himself

against loss in either event. In Ellesmere (Earl) v. Wallace (1928) 2 Ch. 1 the jockey club was not

interested in the result of the races and the provision relating to the prizes was in no way dependent

upon the result of the races as they were to be given in any event, and the only event outstanding

between the parties, viz., whether the defendant's horse would run in the race depended solely on

the volition of the defendant and not upon the determination of any future event.

17. The evidence in the present case shows that the race which was to be run on September 29 was

adjourned to October 6 early in the morning, and still in the afternoon of that day bets were entered

into with regard to the meeting which had already been adjourned, and the bets were to remain

good for the race that was to be run on October 6. The parties did not intend either that the race

should run on September 29 or that a particular horse should run that day, as the condition of the

agreement, I think that even though the race was postponed the agreement to bet would be a wager

and would amount to an offence under Section 5 of the Gambling Act. A question in the present case

is, whether on the evidence accused No. 1 having the use of a room or place in the premises of the

Akbar Manufacturing and Press Company did use the same for the purpose of a common gaming

house, and accused Nos. 2 to 8 did assist accused No. 1 in conducting the business of the said

common gaming house, and thereby accused No. 1 committed an offence punishable under Section

4(a) and accused Nos. 2 to 8 committed an offence punishable under Section 4(c) of Act IV of 1887,

and the learned Magistrate has to find on the evidence whether the room or the place in question is

a, common gaming house, That question would depend on the evidence in the case and the fact that

a particular race was adjourned on September 29 to October 6 does not affect the question.

18. I would, therefore, answer the reference, on the points referred to, as stated above.

Wild, J.

19. This is a reference under Section 452 of the Criminal Procedure Code by the Presidency

Magistrate, 2nd Court, in which he refers live questions for the opinion of this Court.

20. The prosecution out of which this reference arises was one under Section 4 of the Bombay

Prevention of Gambling Act of 1887 and the facts are shortly these. On September 27, 1928, one

Ibrahim Ismail's sworn statement was taken by the Commissioner of Police, Bombay, and he

complained that the premises of the Akbar Manufacturing Co. were being used as a bucket shop or

Emperor vs Ismail Hirji on 4 September, 1929

Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/10988/ 5

office for receiving bets on horses. On September 29, the Commissioner of Police, without issuing a

warrant under Section 6 of the Bombay Prevention of Gambling Act to any other police-officer to

search the premises, himself raided the premises. He entered by the front door and Sub-Inspector

Salaskar entered by the rear or side door. The premises consist of buildings with two open passages

at right angles one to the other. It was found that the passages were being used for the purpose of

betting on horse races that were to take place that day at Poona, Arrests were made; some of the

accused were arrested by Sub-Inspector Salaskar and by one of the Police Constables of his party out

of sight of the Commissioner of Police and others were arrested in his presence. It subsequently

transpired that at the time of the raid the race meeting had been postponed.

21. The first question referred is, whether offences punishable under Section 4 of the Bombay

Prevention of Gambling Act IV of 1887 as modified up to date are cognizable offences in all cases.

The learned Magistrate appears to doubt the correctness of the ruling in Emperor v. Abasbhai (1925)

I.L.R. 50 Bom. 344, s.c. 28 Bom. L.R. 272, though he admits that he is bound to follow it. I am of

opinion that it is not open to the Presidency Magistrate under Section 432 of the Criminal Procedure

Code to refer a point of law which is covered by an authority binding on him nor is it clear on what

ground the learned Presidency Magistrate doubts the correctness of the ruling in Emperor v.

Abasbhai. He refers to the case of Emperor v. Chandri (1924) I.L.R. 49 Bom. 212, S.C. 26 Bom. L.R.

1225. But the facts there were completely different. In that case the arrest for an offence under the

Bombay Prevention of Prostitution Act was not on a complaint or by an authorized police-officer

and the arrest was, therefore, held to be illegal. Here the arrest for an offence under the Bombay

Prevention of Gambling Act was by an officer (the Commissioner of Police, Bombay) who could have

issued a warrant of arrest. The question really is not whether the offence in this cage is a cognizable

one but whether the Commissioner of Police was empowered to arrest. In Emperor v. Fernad (1907)

I.L.R. 31 Bom. 438, s. c. 9 Bom. L.R. 695. it was held that a person who is authorized to issue a

warrant under Section 6 of the Bombay Prevention of Gambling Act could himself arrest without a

warrant and this case was followed in Emperor v. Jaffur Mahomed (1912) I.L. R 37 Bom. 1402, S.C.

15 Bom. L.R. 106, and Emperor v. Abasbhai (1825) I.L.R. 50 Bom. 344, s. c. 28 Bom. L.R. 278. The

principle enunciated in the case of Emperor v. Fernad is a common-sense one. In the case of

Magistrates it has been enacted in Section 65 of the Criminal Procedure Code that they have this

power. As under the Criminal Procedure Cede warrants of arrest are not issued by police-officers, it

was unnecessary for the Code to make a similar provision in the case of police-officers. There would

appear, therefore, to be no reason to suppose that the principle enunciated in the case of Emperor v.

Fernad is incorrect. My answer, therefore, to the first question would be that the Commissioner of

Police of Bombay was in the circumstances of this case authorized to arrest the accused.

22. The second question is, whether the arrests are illegal as there was no complaint on oath and the

passage is not a "place" within the meaning of Section 6 of the Bombay Prevention of Gambling Act.

With regard to the first branch of this question it is not contended by the learned Counsel for the

accused that there is no statement on oath by the informer. It is, however, contended that the word

"complaint" in Article 6 should bear its ordinary meaning of "information given by a person

aggrieved". That, however, is not the meaning of the word "complaint" as defined in the Criminal

Procedure Code, Section 4(1)(g), and as ruled in the case of In re Ganesh Narayan Sathe (1889)

I.L.R. 13 Bom. 600 "any person having knowledge of the commission of an offence, may set the law

Emperor vs Ismail Hirji on 4 September, 1929

Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/10988/ 6

in motion by a complaint, even though he is not personally interested or affected by the offence."

The informant in this case was not interested but it is not necessary to suppose that the word

"complaint" in Section 6 is to be given any other meaning than that which it bears in the Criminal

Procedure Code, I hold then that there was a complaint on oath as required by Section 6.

23. As regards the second branch of the question whether these passages constitute a "place" within

the meaning of Section 6 of the Bombay Prevention of Gambling Act, the facts of the present case

are very similar to those of the case of Emperor v. Fattoo Mahomed (1913) 1. L.K. 37 Bom., 651, s. c.

15 Bom. L.R. 689. There it was held that a small area limited by metes and bounds, surrounded on

all sides by buildings, and appropriated for the business of betting by the accused as a lessee was a

place within the meaning of Section 4. Here the passages are surrounded by buildings and are closed

at night by doors. It is true that the accused have not leased the passages for their business but they

have appropriated them for the business by using them. In this way the business of betting has been

localised and it would seem that this localisation converts the passages into a place as held in the

case just cited. In the Bombay Prevention of Gambling Act, Section 3, "common gaming" house is

defined as a house, room or place in which instruments of gaming are kept, etc., and it is clear from

the ruling just cited that the common factor in the expressions "house, room or place" is not that

they are roofed over but that they are sufficiently definite. In this case as the passages are limited by

the buildings and doors, it would appear that they are a place within the meaning of Sections 3, 4,

and 6 of the Bombay Prevention of Gambling Act.

24. The third question is, whether the Commissioner satisfied himself that there were good grounds

for the suspicion of the complainant. As this is altogether a question of fact, I would leave it to the

learned Presidency Magistrate to decide.

25. The fourth question is, whether the arrests by constables or by Sub-Inspector Salaskar are

illegal. As to this it may be presumed that, before the raid, orders were given by the Commissioner of

Police to Sub-Inspector Salaskar to arrest those who might be found in the passages, It may be that

the arrests were not made within sight of the Commissioner of Police but they can be considered in

the circumstances to have been made in his presence. It can hardly be urged that in a case like this

where a number of persons are to be dealt with, the person authorized to arrest must personally

make the arrest in each case. If the, arrest is made in his presence and on his order it is certainly

sufficient in accordance with the maxim qui facit per alium, facit per sc. I would, therefore, hold that

the arrests by the constables and by Sub-Inspector Salaskar are not illegal.

26. The last question is, whether there is any gaming at all when the meeting was postponed. It is

argued that as it was understood by the bettors on the horses and the accused that the bets were

with respect to races which were to take place that afternoon at Poona and at the time when the bets

were made the races had been postponed there was no gaming in this case, that is to Bay, there was

no wagering or betting. No authority has been cited for the proposition that if one or both parties are

under a misapprehension as to the subject of the wager or bet there is no wager or bet made. All that

the wagerers in a case like this demand is that they should be paid an amount of money if the horse

selected by them wins or is placed at the race in which the horse is to run. When they have made

their bet and it has been accepted by the taker the transaction is a complete wager or bet. It may be

Emperor vs Ismail Hirji on 4 September, 1929

Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/10988/ 7

that "in a case like the present where the race meeting is postponed or cancelled the person who has

paid his money would be entitled to get the money back, but, in my opinion, it cannot be said that

the bet has not been made. Similarly, the abetment of an offence is under the Indian Penal Code

punishable whether the offence abetted is or is not committed. I am, therefore, of opinion that the

fact that the race meeting was in this case postponed does not mean that there was no gaming.

Emperor vs Ismail Hirji on 4 September, 1929

Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/10988/ 8

Вам также может понравиться

- Nadigar Sangam JudgmentДокумент62 страницыNadigar Sangam JudgmentsreevarshaОценок пока нет

- Arudha PadaДокумент16 страницArudha PadaVaraha Mihira100% (11)

- Supreme Court Rules, 2013Документ106 страницSupreme Court Rules, 2013Latest Laws TeamОценок пока нет

- Puducherry RulesДокумент3 страницыPuducherry RulessreevarshaОценок пока нет

- Tamil Nadu Rules and FormДокумент6 страницTamil Nadu Rules and FormsreevarshaОценок пока нет

- VARGA D/10 or DASAMA "MAHAT PHALAM" DASAMSA OR KARMAMSA OR SWARGAMSAДокумент11 страницVARGA D/10 or DASAMA "MAHAT PHALAM" DASAMSA OR KARMAMSA OR SWARGAMSAANTHONY WRITER100% (3)

- Arudha PadaДокумент16 страницArudha PadaVaraha Mihira100% (11)

- Rajendran Vs State Rep. by Inspector of Police On 9 July, 2012Документ6 страницRajendran Vs State Rep. by Inspector of Police On 9 July, 2012sreevarshaОценок пока нет

- 482 After CRL Revision Dismissed MaintainableДокумент10 страниц482 After CRL Revision Dismissed MaintainablesreevarshaОценок пока нет

- Iqbal Vs State of Kerala On 24 October, 2007Документ4 страницыIqbal Vs State of Kerala On 24 October, 2007sreevarshaОценок пока нет

- Special Fee Advocate EnrolmentДокумент21 страницаSpecial Fee Advocate EnrolmentsreevarshaОценок пока нет

- Drugs&Cosmetic ActДокумент284 страницыDrugs&Cosmetic ActsreevarshaОценок пока нет

- Alamelu & Anr Vs State Rep - by Inspector of Police On 18 January, 2011Документ12 страницAlamelu & Anr Vs State Rep - by Inspector of Police On 18 January, 2011sreevarshaОценок пока нет

- P.danapal Vs State Rep. by On 23 March, 2015Документ6 страницP.danapal Vs State Rep. by On 23 March, 2015sreevarshaОценок пока нет

- Supreme Court examines school certificate in juvenile caseДокумент8 страницSupreme Court examines school certificate in juvenile casesreevarshaОценок пока нет

- Sodexo SVC India Pvt. LTD Vs State of Maharashtra and Ors On 9 December, 2015Документ9 страницSodexo SVC India Pvt. LTD Vs State of Maharashtra and Ors On 9 December, 2015sreevarshaОценок пока нет

- 8140 Decisive Battles TextДокумент18 страниц8140 Decisive Battles TextsreevarshaОценок пока нет

- PDFДокумент356 страницPDFsreevarshaОценок пока нет

- Pratap Kishore Panda & Ors Vs Agni Charan Das & Ors On 16 October, 2015Документ8 страницPratap Kishore Panda & Ors Vs Agni Charan Das & Ors On 16 October, 2015sreevarshaОценок пока нет

- 750 Famous Motivational and Inspirational QuotesДокумент53 страницы750 Famous Motivational and Inspirational QuotesSaanchi AgarwalОценок пока нет

- Unlawful AssemblyДокумент3 страницыUnlawful AssemblysreevarshaОценок пока нет

- Shailesh Dhairyawan Vs Mohan Balkrishna Lulla On 16 October, 2015Документ15 страницShailesh Dhairyawan Vs Mohan Balkrishna Lulla On 16 October, 2015sreevarshaОценок пока нет

- Arumugha Pillai Vs Vadivel Pillai On 29 September, 1993Документ5 страницArumugha Pillai Vs Vadivel Pillai On 29 September, 1993sreevarshaОценок пока нет

- Sri CH - Narasimha Rao & Ors Vs Land Acquisition Officer Eluru & ... On 9 December, 2015Документ4 страницыSri CH - Narasimha Rao & Ors Vs Land Acquisition Officer Eluru & ... On 9 December, 2015sreevarshaОценок пока нет

- Indian Oil Corporation LTD Vs A.p.industrial Infractrcture ... On 9 December, 2015Документ8 страницIndian Oil Corporation LTD Vs A.p.industrial Infractrcture ... On 9 December, 2015sreevarshaОценок пока нет

- Balu at Bal Subramaniam & Anr Vs State (U.T. of Pondicherry) On 16 October, 2015Документ6 страницBalu at Bal Subramaniam & Anr Vs State (U.T. of Pondicherry) On 16 October, 2015sreevarshaОценок пока нет

- Rajvinder Singh Vs State of Haryana On 16 October, 2015Документ7 страницRajvinder Singh Vs State of Haryana On 16 October, 2015sreevarshaОценок пока нет

- Veerenndra Kumar Dubey Vs Chief of Army Staff & Ors On 16 October, 2015Документ10 страницVeerenndra Kumar Dubey Vs Chief of Army Staff & Ors On 16 October, 2015sreevarshaОценок пока нет

- Kamal at Poorikamal & Anr Vs State of Tamil Nadu On 16 October, 2015Документ7 страницKamal at Poorikamal & Anr Vs State of Tamil Nadu On 16 October, 2015sreevarshaОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Loans Appraisal GuidelinesДокумент15 страницLoans Appraisal GuidelinesMichael KattaОценок пока нет

- Obligation and Contracts Finals ReviewДокумент12 страницObligation and Contracts Finals ReviewelineОценок пока нет

- ICJ Advisory Opinion - Reparation of Injuries CaseДокумент2 страницыICJ Advisory Opinion - Reparation of Injuries CaseJeniffer Clarrisa AudreyОценок пока нет

- STD Storybooksong NDAДокумент5 страницSTD Storybooksong NDArajeshОценок пока нет

- Cause and Effect, EnglishДокумент18 страницCause and Effect, EnglishCristita M. ComtiagОценок пока нет

- Comparatives Superlatives Worksheet PDFДокумент1 страницаComparatives Superlatives Worksheet PDFÁngela MarcelaОценок пока нет

- Agency Shop and Closed Shop AgreementsДокумент2 страницыAgency Shop and Closed Shop AgreementsOlek Dela Cruz100% (1)

- Fiscal Federalism and Fiscal DecentralizationДокумент6 страницFiscal Federalism and Fiscal DecentralizationSantosh ChhetriОценок пока нет

- Ghenesis Lit Analysis Brownies FinalДокумент6 страницGhenesis Lit Analysis Brownies Finalapi-242939687Оценок пока нет

- Global Migration ReferenceДокумент28 страницGlobal Migration ReferenceBabee HaneОценок пока нет

- Course Outline ACCO 400 - Fall 2023Документ8 страницCourse Outline ACCO 400 - Fall 2023bushrasaleem5699Оценок пока нет

- Supreme Student Governemnt Election Guidelines For S.Y. 2021 2022-2-1 1 REVISEDДокумент18 страницSupreme Student Governemnt Election Guidelines For S.Y. 2021 2022-2-1 1 REVISEDTesda SfistОценок пока нет

- Maxwell MTD Perjury ChargesДокумент19 страницMaxwell MTD Perjury ChargesLaw&CrimeОценок пока нет

- Graph of Vertical and Horizontal Measurements Over TimeДокумент2 страницыGraph of Vertical and Horizontal Measurements Over TimeWan Wan SetyawanОценок пока нет

- Statutory Declaration-Ask PDFДокумент1 страницаStatutory Declaration-Ask PDFAset-Sopdet Kyra ElОценок пока нет

- Competent Mentally Retarded Witness Testifies in Rape CaseДокумент2 страницыCompetent Mentally Retarded Witness Testifies in Rape CaseNOLLIE CALISINGОценок пока нет

- Financial Service CooperativesДокумент11 страницFinancial Service CooperativesJ-zeil Oliamot PelayoОценок пока нет

- FIRST-SEM UCSP1112HBSIf13 Neo Sir-FerdДокумент26 страницFIRST-SEM UCSP1112HBSIf13 Neo Sir-FerdJanice Dano OnaОценок пока нет

- Documento 7Документ2 страницыDocumento 7avillanuevaОценок пока нет

- ENGINEERINGAddlspecialconditionsfor Civil WorksДокумент2 страницыENGINEERINGAddlspecialconditionsfor Civil WorksLAMOS TECHNOLOGY SOLUTIONS PRIVATE LIMITEDОценок пока нет

- Sample Mitchell Scholarship Recommendation: Janet TeacherДокумент3 страницыSample Mitchell Scholarship Recommendation: Janet TeacherDaniel GomesОценок пока нет

- Fees Rscoe 27 Oct 2022Документ1 страницаFees Rscoe 27 Oct 2022Pranav PatiLОценок пока нет

- The History of Today's Slavery v2Документ36 страницThe History of Today's Slavery v2skunkyghostОценок пока нет

- PPSD 1693837801Документ7 страницPPSD 1693837801Tanu RathiОценок пока нет

- Mr. Moore's Motion To Dismiss/Summary JudgmentДокумент9 страницMr. Moore's Motion To Dismiss/Summary JudgmentWXYZ-TV Channel 7 Detroit100% (1)

- Section 100 CPCДокумент12 страницSection 100 CPCAarif Mohammad BilgramiОценок пока нет

- English 2-09-Structure Transisiton QuestionsДокумент8 страницEnglish 2-09-Structure Transisiton QuestionsDing DongОценок пока нет

- ETHICS6375Документ54 страницыETHICS6375nathalieОценок пока нет

- Course Outline For Civil Law Review 2 SPECIAL CONTRACTДокумент4 страницыCourse Outline For Civil Law Review 2 SPECIAL CONTRACTsinodingjr nuskaОценок пока нет

- Remission or Cancellation of Indebtedness: UnclassifiedДокумент22 страницыRemission or Cancellation of Indebtedness: UnclassifiedJacen BondsОценок пока нет