Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Journal of Sustainable Tourism

Загружено:

Gerson Godoy RiquelmeОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Journal of Sustainable Tourism

Загружено:

Gerson Godoy RiquelmeАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

This article was downloaded by: [146.83.207.

4]

On: 21 March 2013, At: 14:22

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered

office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Journal of Sustainable Tourism

Publication details, including instructions for authors and

subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsus20

Littering in protected areas: a

conservation and management

challenge a case study from the

Autonomous Region of Madrid, Spain

David Rodrguez-Rodrguez

a

a

Institute of Economics, Geography and Demography, Spanish

National Research Council (IEGD-CSIC), Albasanz, 26-28, Madrid,

28037, Spain

Version of record first published: 24 Jan 2012.

To cite this article: David Rodrguez-Rodrguez (2012): Littering in protected areas: a conservation

and management challenge a case study from the Autonomous Region of Madrid, Spain, Journal of

Sustainable Tourism, 20:7, 1011-1024

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2011.651221

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-

conditions

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any

substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,

systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation

that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any

instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary

sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings,

demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or

indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Journal of Sustainable Tourism

Vol. 20, No. 7, September 2012, 10111024

Littering in protected areas: a conservation and management challenge

a case study from the Autonomous Region of Madrid, Spain

David Rodrguez-Rodrguez

Institute of Economics, Geography and Demography, Spanish National Research Council

(IEGD-CSIC), Albasanz, 26-28, Madrid 28037, Spain

(Received 31 July 2011; nal version received 9 December 2011)

This paper examines issues surrounding littering in protected areas (PAs), one of the most

ubiquitous and conspicuous impacts of tourism activity. In addition to obvious visual,

landscape-affecting impacts, litter may have hazardous consequences for biodiversity

and humans. In order to precisely assess littering in a densely populated region with high

levels of visitation to natural and protected areas, we counted, measured and classied

all types of non-organic litter covering an area of 1 cm

2

or more found on the ground

in zones intensively used by visitors (picnic areas and paths) within the 10 PAs of the

Autonomous Region of Madrid. On average, 11.65 m

2

/ha of litter were recorded in

those zones. Strict visitor management measures greatly reduced that gure. Over 75%

of all litter was paper and cardboard, and plastic; 88% of litter coverage was by large

pieces over 25 cm

2

in size. We tested the hypothesis that the amount of waste found on

paths is correlated with the distance to the entrance to a PA, but no general model tted

actual litter distribution patterns, although empirical results backed the hypothesis for

most cases. Arange of waste management strategies are explored and litter management

measures suggested for problematic PAs.

Keywords: visitor impact; littering; protected areas; management; Autonomous Region

of Madrid; zones intensively used by visitors

Introduction

Tourism in protected areas: a management challenge

Tourism in natural and protected areas (PAs) has been increasing rapidly across the world

(Buckley, Weaver, & Pickering, 2003; Farrell & Marion, 2001; Mulero, 2002). This fast-

growing public use has overwhelmed the carrying capacities and tourism infrastructures of

some PAs (Corraliza, Garca-Navarro, & Valero, 2002; Tisdell, 2001). Numerous manage-

ment and conservation problems have arisen, especially in the most popular areas (Farrell,

2002; Hunter & Green, 1995; Kaseva & Moirana, 2010; Leung & Marion, 1999)

Visitor impacts on natural and protected areas are diverse and serious (Tisdell, 2001). Di-

rect impacts include: increasing use of resources; soil trampling and compacting; vegetation

removal; animal disturbance; soil erosion; littering; water pollution; noise making; introduc-

tion of alien species and varieties; damage to geological features, cultural sites, vegetation

or public use infrastructure; increased re risk; air pollution from transportation; animal

road kills; and changes in wildlife behavioural patterns due to human habituation (Chape,

Spalding, & Jenkins, 2008; Farrell, 2002; Hunter & Green, 1995; Kaseva & Moirana, 2010;

Email: david.rodriguez@csic.es

ISSN 0966-9582 print / ISSN 1747-7646 online

C

2012 Taylor & Francis

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2011.651221

http://www.tandfonline.com

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

4

6

.

8

3

.

2

0

7

.

4

]

a

t

1

4

:

2

2

2

1

M

a

r

c

h

2

0

1

3

1012 D. Rodrguez-Rodrguez

Liddle, 1997). Due to the potential cumulative effects of these impacts and the sensitivity

of many natural areas, it is vital for the conservation of natural resources that these impacts

are assessed and anticipated (Newsome, Moore & Dowling, 2002). Nevertheless, many

of them have received relatively little research attention, despite their ecological signi-

cance and the needs of PA managers for visitor impact monitoring and prediction (Buckley

et al., 2003; Farrell & Marion, 2001). Most research has focused on the most conspicuous

impacts, such as vegetation damage, soil trampling, waste disposal or disturbance to avian

fauna (Buckley et al., 2003, Hunter & Green, 1995). New quick, low-cost methodologies

for complete visitor impact assessment and mapping remain a management need (Liddle,

1997).

Heavily visited PAs can be deemed contested sites where a diversity of visitors has

different ideas and needs about the use of the place (Mc Kercher & Weber, 2008). In those

places, visitor impacts may also result in a reduced quality of recreational experiences and

in conicts among visitors (Brown, Ham, & Hughes, 2010; Farrell, 2002; Leung & Marion,

1999).

Littering: an undesirable and ever-present impact of tourism in PAs

Littering is one of the most ubiquitous and conspicuous impacts of tourism in PAs. The

impacts of littering in the most visited zones are many and serious (Brown et al., 2010;

Kaseva & Moirana, 2010). In addition to detracting from the visual quality of an area, litter

may also act as a hazardous source of pollution to wildlife (often endangered), soil, water

and humans, depending on the toxicity and the environment of the disposed litter (Brown

et al., 2010; Buckley et al., 2003). Despite the importance of littering for management,

for the social perception of PAs and for the conservation of PAs (Diego & Garca-Codron,

2006), little specic research on the topic has been developed.

Conservation and management problems posed by visitor impacts to PAs, such as those

arising from littering, tend to concentrate in the most visited places, such as picnic areas

or paths (Farrell & Marion, 2001), as the amount of litter found is related to the number

of visitors (Kaseva & Moirana, 2010). Due to the fact that many visitors to PAs are quite

sedentary (G omez-Lim on, 2002; G omez-Lim on, M ugica, Medina, & De Lucio, 1994), it

may be thought that litter density along paths inside PAs would decrease with distance from

the entrances to PAs.

The context of the PAs of the Autonomous Region of Madrid

A total of 6.5 million people live in the ARM, within an area of 8021 km

2

(Instituto

Nacional de Estadstica [INE], 2011). While containing Spains capital city and nine other

cities over 100,000 inhabitants, it also has large tracts of unspoilt countryside and a rich

cultural and biological heritage (Aramburu, Escribano, Ramos, & Rubio, 2003; De Miguel

& Daz-Pineda, 2003; Vacas, 2006).

The process of progressive overcrowding by visitors is not new to the 10 PAs of the

Autonomous Region of Madrid (ARM) in Spain, especially to the best-known ones such

as Pe nalara Natural Park, Pinar de Abantos y Zona de la Herrera Picturesque Landscape

and Cuenca Alta del Manzanares Regional Park (Barrado, 1999; G omez-Lim on, M ugica,

Mu noz, & De Lucio, 1996; Rodrguez-Rodrguez, 2009).

Even in 1993, an estimated 2,800,000 people visited picnic areas inside the regions PAs

(G omez-Lim on et al., 1996). This number continues to grow. Pressures from mass tourism

and visitation have become so important in this densely populated region that tourism

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

4

6

.

8

3

.

2

0

7

.

4

]

a

t

1

4

:

2

2

2

1

M

a

r

c

h

2

0

1

3

Journal of Sustainable Tourism 1013

has been identied as the main current threat to the conservation of its PAs (Rodrguez-

Rodrguez, 2008). The inux of visitors to the PAs in the region is seasonal. The PAs located

in the dry south-east receive the bulk of visitors in spring time (May), whereas those in the

mountainous north-west are most visited in summer time (July) (G omez-Lim on et al., 1996).

Despite the serious environmental problems caused by high visitor numbers (Barrado, 1999;

G omez-Lim on & Garca-Avil es, 1992; G omez-Lim on et al., 1996; Rodrguez-Rodrguez,

2008), public use is neither assessed nor regulated sufciently. Only one of the 10 regions

PAs has an accurate register of visitor gures due to the existence of a daily visitor quota:

the National Site of Natural Interest of Hayedo de Montejo de la Sierra. There is also no

clear policy on litter management inside the PAs. In some, notably in the parks, some public

use infrastructure, such as litter bins or interpretive panels informing visitors about the PA,

is in place, although such bins/panels are not present in every picnic area or PA entrance

and very few panels address littering specically. In these PAs, cleaning patrols operate

on an alternating basis (not daily), cleaning and tidying up the picnic areas (including

vegetation pruning). Cuenca Alta del Manzanares Regional Park operates a trash-in/trash-

out policy in the most popular area of the Park (access to Canto Cochino), whereby the

parks staff located at the main entrance inform visitors of the need to take out their litter

and offer visitors a rubbish bag to put it in, as in some popular PAs elsewhere in the world

(Kaseva & Moirana, 2010). PAs other than parks generally lack any sort of public use

infrastructure or regular staff to collect litter or to inform visitors to take out their own

rubbish.

Most visitors to the regions PAs come from urban centres where litter-collecting fa-

cilities are usually in place and they are, therefore, less aware of the impacts of littering

in natural areas, to which they often are outsiders (Brown et al., 2010; Mc Kercher &

Weber, 2008). However, education, which is seen as an effective means to raise visitors

awareness of their own impacts on visited places and to modify their behaviour (Brown et

al., 2010), is not regularly used as a management tool to prevent littering in the PAs of the

ARM.

The last studies of the impacts of public use in the PAs of the ARM that included some

assessment of littering were conducted over 15 years ago (G omez-Lim on & Garca-Avil es,

1992; G omez-Lim on et al., 1996). The huge urban and demographic changes experienced

by the region since then (De Miguel & Daz-Pineda, 2003; Naredo & Fras, 2005) have

posed additional pressures for its PAs (Rodrguez-Rodrguez, 2008). There is an urgent

need for more effective management and conservation and to make that process work,

knowledge of the amount, distribution and types of litter found on the ground in the most

visited zones inside the PAs will signicantly enhance the managers capacity to deal with

this challenge.

Aims of the study

This study had three main aims. The rst was measuring, classifying and comparing the

amount and types of litter found in zones with intensive visitor use in the PAs of the

ARM to assess the current impact of this variable closely linked to tourism. The sec-

ond aim was testing the hypothesis that the density of litter found on paths was nega-

tively correlated with the distance to the entry points to PAs. The last aim was to explore

some litter management strategies and measures to enhance the conservation state of the

regions PAs.

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

4

6

.

8

3

.

2

0

7

.

4

]

a

t

1

4

:

2

2

2

1

M

a

r

c

h

2

0

1

3

1014 D. Rodrguez-Rodrguez

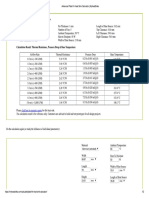

Table 1. Protected areas of the Autonomous Region of Madrid where the survey was conducted,

category, area, type of surveyed zone, number of surveyed zones, and number of times each zone

was surveyed.

Protected area Location Category

Hectares

(ha)

Type of

surveyed

zone

Number of

surveyed

zones

Times

surveyed

Cuenca Alta NW Regional park 52,796 Picnic area 8 1

Sureste SE Regional park 31,550 Picnic area 9 (1

non-valid)

1

Guadarrama SE Regional park 22,116 Picnic area 4 1

Pe nalara NW Natural park 11,530 Picnic area 2 1

Abantos y Herrera NW Picturesque

landscape

1538 Picnic area 5 (1

non-valid)

1

Regajal-Ontgola SE Nature reserve 629 Path 1 2

Hayedo Montejo NW Natural site of

national

interest

250 Path 1 1

Pe na del Arcipreste NW Natural

monument of

national

interest

3 Path 1 2

Laguna de San Juan SE Fauna refuge 47 Path 1 2

Soto Henares SE Preventive

protection

regime

332 Path 1 2

Materials and methods

We selected paths and picnic areas within the 10 PAs of the ARM as the zones most

intensively used by visitors to those PAs (see Table 1) (Farrell & Marion, 2001; G omez-

Lim on et al., 1996; Kaseva & Moirana, 2010). We made a census of the litter found on the

ground in these zones. We divided the 10 PAs into two geographical groups (SE, NW) and

temporally distributed the census during two non-consecutive months in 2009 according to

the annual maximum inux of visitors reported to each group of PAs (G omez-Lim on et al.,

1994) (Figure 1):

May for the SE PAs: Sureste Regional Park, Laguna de San Juan Fauna Refuge, El

Regajal-Mar de Ontgola Nature Reserve, Preventive Protection Regime of Soto del

Henares and Guadarrama Regional Park (17 zones); and

July for the NW PAs: Pe nalara Natural Park, Cuenca Alta del Manzanares Regional

Park, Natural Site of National Interest of Hayedo de Montejo, Natural Monument of

National Interest of Pe na del Arcipreste de Hita and Pinar de Abantos y Zona de La

Herrera Picturesque Landscape (17 zones).

For the purpose of this study, we used consistently the word litter to refer to all kinds

of waste disposed by visitors into PAs. The term includes wastes commonly found in these

PAs such as hunting ammunition, old tyres, rubble, etc. Organic waste was not considered

as litter in this study because of its restricted amount, biodegradable nature and limited

polluting effects.

We made the censuses early on weekday mornings, thus nding the zones as they were

left by visitors from the previous days and usually before cleaning patrols reached them.

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

4

6

.

8

3

.

2

0

7

.

4

]

a

t

1

4

:

2

2

2

1

M

a

r

c

h

2

0

1

3

Journal of Sustainable Tourism 1015

Figure 1. Location of the surveyed zones within the protected areas of the Autonomous Region of

Madrid.

Source: The author.

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

4

6

.

8

3

.

2

0

7

.

4

]

a

t

1

4

:

2

2

2

1

M

a

r

c

h

2

0

1

3

1016 D. Rodrguez-Rodrguez

As cleaning patrols do not operate on a daily basis or during the weekends, we hoped to

reect the worst possible litter situation in each PA (Farrell & Marion, 2001). The censuses

were not performed on weekends because the high number of visitors in the biggest and

most popular zones would have severely hampered data collection. Censuses performed

on Mondays therefore usually reect the worst possible situation. Thus, the census dates

were distributed so that at least one randomly chosen zone from each PA was surveyed on

a Monday morning (except for Hayedo de Montejo).

We selected all the zones intensively used by visitors (picnic areas and paths) within the

10 PAs as the target manageable zones where the largest quantity of litter was likely to be

found. Big PAs (over 1000 ha) are the only ones with picnic areas inside their boundaries,

where most visitors tend to concentrate (Barrado, 1999). In addition, big PAs have several

entrance points and a huge number of paths inside them, not all of them clearly identied,

which makes it impossible to perform a census on all paths or even appropriately count

and sample them. In contrast, small PAs (under 1000 ha) have few but identiable entrance

points and paths where most visitors concentrate, as no picnic areas are available. In both

cases, for picnic areas and paths, we noted down the total surveyed area (of each picnic

area or path), the type of litter found on the ground and its estimated area, and performed

the census according to the physical characteristics of both types of zones:

(1) In big PAs (over 1000 ha, ve PAs): we visually estimated the area (cm

2

) covered

by different types of litter found inside picnic areas (n = 28; the census could not

be performed in two picnic areas due to the presence of free cattle). We surveyed

the total area covered by each picnic area through regular 3-m parallel transects and

noted down every litter item equal to or over 1 cm

2

found. We annotated the GPS

coordinates of the picnic areas corners to calculate their area using GIS software

(Arc-GIS). Picnic areas inside each PA were surveyed consecutively on different

weekdays.

(2) In small PAs (under 1000 ha, ve PAs): we visually estimated litter equal to or over

1 cm

2

found along paths starting from the main entrance(s) to the PA and nishing

1000 m inside the PA (or before, if the path was shorter). We noted the type of litter,

its quantity, its estimated area (cm

2

) and the distance from the starting point of the

path where each item was found using a 10-m recording pedometer. We surveyed

the area comprised by the paths width and a 1-m band along each side of the path

as the most likely zone to nd litter due to public use. To calculate the surveyed

area, we considered the average width of the paths, together with the total 2-m

side band, and their length. Paths lengths ranged from 480 to 1160 m. One path

per small PA was surveyed. Average litter quantity from two transects per PA was

taken. Both censuses were made on different non-consecutive weekdays, differing

over 15 days for the same path to reect a different range of situations within the

time frame of the study. For Hayedo de Montejo, it was assumed that the quantity

of litter found would be equal in any day, as the entrance is controlled and visit is

guided at all times, so only one transect was done. We excluded Hayedo de Montejo

(n =1) from most statistical analyses due to the fact that litter dynamics are totally

different in this PA as a result of this strict access control.

In the small PAs, we tested the initial hypothesis that states that the amount of litter,

measured by its covered area on the ground, should be higher in places with easy accessibil-

ity, such as the entrances to PAs and their surroundings, than in other places far away from

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

4

6

.

8

3

.

2

0

7

.

4

]

a

t

1

4

:

2

2

2

1

M

a

r

c

h

2

0

1

3

Journal of Sustainable Tourism 1017

Table 2. Standard area of most common litter completely extended (cm

2

).

Common waste Measures Area (cm

2

)

Plastic bag 28 cm 38 cm 1064

Plastic bottle 5 L 30 cm 15 cm 450

Plastic bottle 2 L 34 cm 9 cm 306

Plastic bottle 1.5 L 32 cm 8 cm 256

Plastic bottle 1 L 25 cm 7.5 cm 187.5

Plastic bottle 0.5 L 22 cm 6 cm 132

Glass bottle 0.25 L 18 cm 5 cm 90

Refreshment can 0.33 L 11 cm 6 cm 66

Cigarette packet 9 cm 5.5 cm 49.5

Brick 0.2 L 12 cm 4.5 cm 54

Brick 1 L 18 cm 10 cm 180

Food can 6.5 cm 6.5 cm 42.25

Paper tissue 20.5 cm 20.5 cm 420.25

Cigarette butt 2.5 cm 1 cm 2.5

Hunting ammunition 6 cm 2 cm 12

Cork 4 cm 2 cm 8

them. We expected that the amount of litter would decrease from the entrance to the PA and

the rst meters of the paths onwards inside the PA. We calculated the average accumulated

percentage of litter per path length using 10-m intervals in order to visually and statisti-

cally analyze litter spatial distribution and to consider the appropriateness of developing

a litter distribution model. All surveys were done by the author, which reduced variation

related to procedure and litter area estimation. The area covered by litter on the ground was

calculated assuming each item covered the maximum possible area (i.e. intact, completely

extended litter). To do so, one model item per type of litter considered was selected from

home rubbish and measured under controlled conditions. We used the standard area values

provided in Table 2 for each of the most common types of litter found on the ground. The

classication of litter was made according to categories shown in Table 3. We performed

one-way ANOVAs (analyses of variance) and linear regression analyses at 1 = 0.95

using SPSS software for data processing and analysis.

Table 3. Categories of litter considered.

Type of litter Categories

Paper and cardboard 1

Plastic (including aluminium paper) 2

Cartons 3

Metal 4

Glass 5

Diverse non-hazardous (rubble, fabric, pottery, footwear, cork and others) 6

Toxic and hazardous (hunting ammunition, oil and detergent containers, batteries,

cigarette butts and others)

7

Sand, dead leaves, dead wood, organic waste Not

included

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

4

6

.

8

3

.

2

0

7

.

4

]

a

t

1

4

:

2

2

2

1

M

a

r

c

h

2

0

1

3

1018 D. Rodrguez-Rodrguez

Table 4. Surveyed area and absolute and relative litter area found in large and small protected areas

of the Autonomous Region of Madrid.

Large protected areas Cuenca Alta Sureste Guadarrama Pe nalara

Abantos y

Herrera

Surveyed area (m

2

) 104,621.08 103,043.22 70,390.60 24,255.47 32,497.01

Absolute average litter

area (m

2

)

31.22 132.66 33.62 4.22 8.31

Relative average litter

area (m

2

waste/ha

surveyed area)

2.98 12.87 4.78 1.74 2.56

Number of picnic areas

surveyed (valid)

8 8 4 2 4

Regajal- Hayedo Pe na Laguna Soto

Small protected areas Ontgola Montejo Arcipreste San Juan Henares

Average surveyed area

(m

2

)

2831.50 4000.00 5265.00 2575.00 5500.00

Litter area (m

2

):

Transect 1

3.16 0.01 1.26 Non-valid 60.41

Litter area (m

2

):

Transect 2

6.30 1.45 0.52 31.61

Absolute average litter

area (m

2

)

4.73 0.01 1.35 0.52 46.01

Relative average litter

area (m

2

litter/ha

surveyed area)

16.71 0.01 2.57 2.02 83.66

Results

In total, 11.65 m

2

/ha of litter were recorded on average in zones intensively used by visitors

inside the PAs of the ARM(95%condence interval, CI

95%

=4.1719.12, n =33, excluding

Hayedo Montejo, Table 4). For picnic areas inside the ve large PAs, the value was 6.78

m

2

/ha (CI

95%

= 3.679.89, Table 5). However, no signicant differences were found in

the relative amount of litter found (Ln) between paths (n = 8) and picnic areas (n = 26)

(p = 0.058, for all PAs, and p = 0.703 without Soto Henares).

There were signicant differences in the relative litter area found among PAs

(p = 0.001) (Ln cm

2

litter/m

2

surveyed area). Inter-pairs contrasts showed an increasing

gradient of the amount of litter found for three groups of PAs:

(1) Laguna San Juan, Pe nalara, Cuenca Alta, Pe na Arcipreste, Abantos y Herrera and

Guadarrama

(2) Sureste and Regajal-Ontgola

(3) Soto Henares

The proportion of the different types of litter found on each PA is shown in Table 6.

The distribution of litter by size is shown in Table 7.

Not considering Hayedo de Montejo, average small-sized litter area (under or equal

to 25 cm

2

) in all the remaining free-access PAs accounted for 11.70% of the total litter

area (CI

95%

= 7.3416.07) and average big-sized litter area (over 25 cm

2

) was 88.30%

of the total litter area (CI

95%

= 83.9392.66). The area covered by small litter is lineally

independent from the area covered by big litter in the zones intensively used by visitors

inside PAs (p = 0.705; R

2

= 0.005).

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

4

6

.

8

3

.

2

0

7

.

4

]

a

t

1

4

:

2

2

2

1

M

a

r

c

h

2

0

1

3

Journal of Sustainable Tourism 1019

Table 5. Absolute and relative litter area per surveyed picnic area.

Absolute litter Picnic area Relative litter

Protected area Picnic area area (cm

2

) (m

2

) area (cm

2

/m

2

)

Cuenca Alta Arroyo Mediano 12,688.75 6704.96 1.89

Las Vueltas 34,292.25 5786.13 5.93

Puente de Madrid 2450.25 6171.19 0.40

Las Dehesas 30,929.25 26,784.07 1.15

La Cabilda 19,767.75 14,023.53 1.41

Canto Cochino 64,703.00 14,750.28 4.39

El Berzalejo 107,541.50 18,196.63 5.91

Chopera del Samburiel 39,819.25 12,204.31 3.26

Sureste Las Islillas 71,341.75 12,539.43 5.69

Laguna del Campillo 34,824.00 2112.44 16.49

Soto Bayona 52,062.25 15,358.85 3.39

El Puente 802,989.25 36,577.72 21.95

Arroyo Palomero 104,696.75 11,861.65 8.83

Pinar Lagunas 121,550.00 18,676.46 6.51

Fuente del Valle 120,878.75 3430.92 35.23

Paseo Abujeta 18,256.50 2485.75 7.34

El Carrascal Census not Census not Census not

possible possible possible

Guadarrama Puente del Retamar 28,380.50 11,437.61 2.48

Parque de San Isidro 51,514.50 9482.93 5.43

El Sotillo 111,825.25 27,138.55 4.12

Picnic de Batres 144,526.25 22,331.51 6.47

Pe nalara Las Presillas 39,908.50 23,396.52 1.71

La Isla 2245.50 858.95 2.61

Abantos y Herrera Silla de Felipe II 21,602.25 2817.23 7.67

Fuente Arenitas 31,258.00 2254.84 13.86

La Penosilla 9150.50 9361.82 0.98

El Tomillar 21,089.25 18,063.13 1.17

Los Llanillos Census not Census not Census not

possible possible possible

Table 6. Absolute proportion of different types of litter found in different protected areas of the

Autonomous Region of Madrid, according to the litter categories shown in Table 3: 1 = paper &

cardboard, 2 = plastic, 3 = cartons, 4 = metal, 5 = glass, 6 = diverse non-hazardous and 7 = toxic

and hazardous.

Litter type

Protected area 1 (%) 2 (%) 3 (%) 4 (%) 5 (%) 6 (%) 7 (%) Total (%)

Cuenca Alta 51.32 30.38 0.28 1.12 0.53 14.31 2.05 100

Sureste 42.91 28.54 0.32 0.49 0.62 26.20 0.91 100

Guadarrama 31.24 42.24 0.17 0.26 0.75 24.64 0.69 100

Pe nalara 43.06 51.42 0.51 1.10 0.00 0.23 3.68

100

Abantos y Herrera 63.05 33.07 0.06 0.40 0.62 1.23 1.57 100

Regajal- Ontgola 26.25 17.66 0.13 0.54 0.26 55.11 0.05 100

Hayedo Montejo 25.86 74.14 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 100

Pe na Arcipreste 56.67 35.16 1.48 5.36 1.33 0.00 0.01 100

Laguna San Juan 81.99 5.18 0.00 1.27 0.00 11.52 0.05 100

Soto Henares 7.24 24.45 0.29 0.59 0.00 66.40 1.03 100

Total average 44.48 31.16 0.47 1.16 0.69 20,58 1.27 100

All were cigarette butts.

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

4

6

.

8

3

.

2

0

7

.

4

]

a

t

1

4

:

2

2

2

1

M

a

r

c

h

2

0

1

3

1020 D. Rodrguez-Rodrguez

Table 7. Proportion of small and large litter in different protected areas of the Autonomous Region

of Madrid.

Litter size (%)

Protected area Small (25 cm

2

) Large (>25 cm

2

)

Cuenca Alta 19.53 80.47

Sureste 6.77 93.23

Guadarrama 9.46 90.54

Pe nalara 19.82 80.18

Abantos 19.92 80.08

Regajal-Mar de Ontgola 2.08 97.92

Hayedo de Montejo

100 0

Pe na del Arcipreste 2.27 97.73

Laguna de San Juan 2.10 97.90

Soto del Henares 0.18 99.82

Average 11.70 88.30

Strict visitor control in place.

A model could not be tted to explain the spatial distribution of litter along the paths

due to the different distribution patterns of litter on each path (Figure 2). Thus, the initial

hypothesis that the amount of litter diminishes with the distance to the entrances to PAs

could not be statistically conrmed. However, for the paths examined and regardless of

their length, empirical results seemed to back the hypothesis: the absolute area covered

by litter found in the rst third of each paths length ranged between 46.70% and 89.96%

of the total litter area on the paths, with an average of 70.47%, clearly over the 33.33%

expected from regular disposal. For the second third of each path, the area covered by litter

ranged between 4.85% and 45.21%, with an average of 17.09%, notably under the expected

33.33%. Finally, the area covered by litter on the last third ranged between 27.00% and

1.38% of the total, with an average of 12.44%, remarkably under the 33.33% expected from

regular disposal.

Figure 2. Spatial distribution of the area covered by litter along paths inside small protected areas

of the Autonomous Region of Madrid. (Color gure available online.)

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

4

6

.

8

3

.

2

0

7

.

4

]

a

t

1

4

:

2

2

2

1

M

a

r

c

h

2

0

1

3

Journal of Sustainable Tourism 1021

Discussion

The amount of litter found on zones intensively used by visitors to the PAs was high,

taking into account that this litter was found in the wildest and most important areas

for nature conservation of the region. Littering in these PAs is an even more serious issue,

taking into account that organic waste was not considered in this study, and that further

litter is likely to be located outside the surveyed area or remained unnoticed due to visitors

hiding their litter (Kaseva & Moirana, 2010). The urban origin of most visitors, their

decient environmental consciousness and the lack of specic facilities in place regarding

littering may explain the large amount of litter found (Brown et al., 2010; Chang, 2010;

Mc Kercher & Weber, 2008). Nevertheless, some uncertainty should be considered when

interpreting the results, mainly regarding the period when the survey was conducted and

the census procedure (visual counting and average paths area measurement and litter size

estimation).

By comparing the area covered by litter on the ground related to the total surveyed area,

and taking into account the assumptions of this study, it cannot be said that picnic areas were

cleaner than paths, the exception being Soto del Henares. The fact that the inux of visitors

to picnic areas may be higher than to paths and that the activities performed in picnic areas

are usually more sedentary than on paths (G omez-Lim on, 2002; G omez-Lim on et al., 1994;

G omez-Lim on et al., 1996; M ugica, 1994) may result in picnic areas being more prone to

the accumulation of litter. However, cleaning patrols operate more frequently in picnic areas

than along paths, and picnic areas often have some facilities for environmental information

and/or litter collection in place, which is almost completely lacking on paths. Therefore,

current litter management measures in picnic areas seem not to be efcient enough to

make a difference compared to the current no-management policy that occurs on the

paths.

The biggest amount of litter by far was found in Soto del Henares. This may be a

consequence of its lack of management (it also lacks all kinds of visitors infrastructure) as

well as of its peri-urban nature (Rodrguez-Rodrguez, 2008). Litter management measures

are urgently needed in this PA, as there we found both the highest quantity of litter per

surveyed area and the highest amount of toxic and hazardous litter per surveyed area,

with a big difference from the other PAs. The bad state of Sureste Regional Park and

of El Regajal-Mar de Ontgola Nature Reserve (a small PA of the highest conservation

value in the region) is also remarkable. Both suffer from lack of effective visitor and litter

management, in spite of the fact that both of them had a director when the study was

done. They appear both dirty and neglected. In addition to the high quantity of litter in

El Regajal-Mar de Ontgola, all visitor infrastructures (information panels and a fauna

observation tower) are useless for their public use duties: they are either vandalised or

destroyed. It is likely that proper installation and maintenance of preventive infrastructure

such as litter bins or explanatory panels at sensible points in these PAs (entrance, public use

zones, etc.) would improve visitors environmental awareness and performance inside them

and thus help reduce the amount of litter disposed (Brown et al., 2010; Hunter & Green,

1995).

There is an inverse relationship between measures controlling visitor access to a PA

and the amount of litter found inside it (G omez-Lim on et al., 1996; Kaseva & Moirana,

2010). The fact that Hayedo de Montejo, where the entrance is controlled and visits are

guided and restricted to small groups at all times, was the cleanest PA by far conrms

that direct approaches to visitor management such as visitor quotas, guided visits, entrance

fees or access restriction to sensitive zones (Rodrguez-Rodrguez, 2009) are effective in

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

4

6

.

8

3

.

2

0

7

.

4

]

a

t

1

4

:

2

2

2

1

M

a

r

c

h

2

0

1

3

1022 D. Rodrguez-Rodrguez

addressing inappropriate visitor behaviour (Chang, 2010). However, the fact that most

visitors are unaware of their own impacts when visiting natural areas (Hillery, Nancarrow,

Grifn, & Syme 2001) reveals a key gap related to environmental education.

The main types of litter found were paper and cardboard and plastic, accounting for

over 75% of the total waste area. Similar proportions were obtained by Kaseva & Moirana

(2010) in Mount Kilimanjaro National Park.

It is likely that littering on paths distributes randomly or according to a set of variables

difcult to identify, measure and model, such as the existence of hidden places for littering,

such as bends or places with dense vegetation (Kaseva &Moirana, 2010). It was empirically

noticed that places below or around public use infrastructure (benches, swings, tables, etc.)

had a bigger area covered by litter than places further away from them, although specic

studies conrming that hypothesis should be done. Even though a model explaining the

spatial distribution of litter on paths could not be found, an interesting empirical nding

was made: in all the paths considered and despite their limited length, the biggest area

covered by litter was found on the rst third of each path. This nding may have interesting

applications for the management of litter in the PAs in the region, for instance, regarding

the installation of litter infrastructure such as litter bins, containers or informative panels.

These would be more useful when located within the rst few meters of the paths and

mainly at the entrances to the paths, as an average of 38.89% (48.61% not considering

Hayedo de Montejo) of the total litter area found in the surveyed paths was found within

the rst 10 m of the entrance to the PA.

Conclusions

Littering is a serious and widespread impact of visitation to the PAs of the ARM, affecting

their visual attraction and conservation status.

All the regions PAs, except one, are notably affected by littering and three of them

(all located in the south-east) are heavily affected. The variables explaining the causes of

littering and the distribution of litter in natural areas could not be clearly identied and,

as a result, this topic remains a scientic and management issue. In spite of this lack of

knowledge, some public use management measures could be taken in the most problematic

PAs. These measures need not necessarily include the prohibition or regulation of access (as

happens in the cleanest PA, Hayedo de Montejo), but may comprise some other indirect

measures instead such as educational briengs or chats prior to the entrance to the PAs

and/or the installation and proper maintenance of preventive infrastructure such as litter

bins or explanatory panels at sensible points (entrances, viewpoints, picnic areas, other

recreation areas, etc.) (Chang, 2010). The trash-in/trash-out scheme seems a promising

system to manage littering, provided that an extensive educational programme explaining

it to visitors is implemented previously (Kaseva & Moirana, 2010).

The preventive approach to managing littering in PAs requires substantial resources

in the form of interpretive panels and educational staff. It may, however, become protable

in the long term against the current reactive approach relying on regular cleaning patrols.

Whereas indirect approaches may be effective, cheaper and less controversial than direct

ones to solve visitor impacts on PAs (Brown et al., 2010; Chang, 2010), direct visitor

management measures may be the only effective means to prevent inappropriate visitor

behaviour in the absence of adequate educational or interpretive facilities (Chang, 2010).

Whatever strategy or measures are chosen to address visitors impacts on PAs, they should

always consider the specicities and the context of each PA to be effective.

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

4

6

.

8

3

.

2

0

7

.

4

]

a

t

1

4

:

2

2

2

1

M

a

r

c

h

2

0

1

3

Journal of Sustainable Tourism 1023

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Javier Martnez Vega for his useful comments on the early drafts of

this paper, and Jos e Manuel Rojo, and Jorge Morales, of the Spanish National Research Council, for

their assistance with data analyses and gure composition.

Note on contributor

David Rodrguez-Rodrguez graduated in Biology from the Complutense University of Madrid and

in Environmental Science from the Autonomous University of Madrid. He was awarded his post-

graduate degree in Conservation Biology by the same university. He also graduated in Environmental

Sciences fromthe Autonomous University of Madrid. He holds an MSc degree in Ecological Restora-

tion from the University of Alcal a de Henares. Currently, he is concluding his PhD thesis on the

integrated assessment of the protected areas of the Region of Madrid at the Institute of Economics,

Geography and Demography of the Spanish National Research Council (IEGD-CSIC).

References

Aramburu, M.P., Escribano, R., Ramos, S., & Rubio, R. (2003). Cartografa del paisaje de la

Comunidad de Madrid [Landscape cartography of the ARM]. Madrid: Consejera de Medio

Ambiente, Comunidad de Madrid.

Barrado, D.A. (1999). Actividades de ocio y recreativas en el medio natural de la Comunidad de

Madrid. La ciudad a la b usqueda de la naturaleza [Leisure activities in the natural environment

of the ARM. The city in search of nature]. Madrid: Consejera de Medio Ambiente, Comunidad

de Madrid.

Brown, T.J., Ham, S.H., & Hughes, M. (2010). Picking up litter: An application of theory-based

communication to inuence tourist behaviour in protected areas. Journal of Sustainable Tourism,

18(7), 879900.

Buckley, R., Weaver, D.B., & Pickering, C. (Eds). (2003). Nature-based tourism, environment and

land management. Wallingford: CABI Publishing.

Chang, L.C. (2010). The effects of moral emotions and justications on visitors intention to pick

owers in a forest recreation area in Taiwan. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(1), 137150.

Chape, S., Spalding, M., & Jenkins, M.D. (Eds). (2008). The worlds protected areas. Prepared by the

UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Corraliza, J.A., Garca-Navarro, J., & Valero, E. (2002). Los Parques Naturales en Espa na: Conser-

vaci on y disfrute [Natural parks in Spain: Their conservation and enjoyment]. Madrid: Mundi-

Prensa.

De Miguel, J.M., & Daz-Pineda, F. (2003). Medio ambiente. Problemas y posibilidades [Envi-

ronment. Problems and possibilities]. In Garca-Delgado, J.L. (Dir.). Estructura econ omica de

Madrid [Economic structure of Madrid] (2nd ed., pp. 181222). Madrid: Consejera de Justicia

e Innovaci on Tecnol ogica. Comunidad de Madrid.

Diego, C., &Garca-Codron, J.C. (2006). Los espacios naturales protegidos [Protected areas]. Matar o:

Davinci.

Farrell, T.A. (2002). The Protected Area Visitor Impact Management (PAVIM) Framework: A sim-

plied process for making management decisions. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 10, 3151.

Farrell, T.A. & Marion, J.L. (2001). Identifying and assessing ecotourism visitor impacts at eight

protected areas in Costa Rica and Belize. Environmental Conservation, 28(3), 215225.

G omez-Lim on, J. (Coord). 2002. Los visitantes de la Comarca de Do nana [The visitors to the Do nana

Region]. Huelva: Fundaci on Do nana 21.

G omez-Lim on, J., & Garca-Avil es, J. (1992). Estudio del impacto de las actividades recreativas en

dos cauces uviales del Parque Regional de la Cuenca Alta del Manzanares (

Area de La Pedriza)

[Study on the impact of recreational activities in two rivers of the Cuenca Alta del Manzanares

Regional Park (La Pedriza)], Series document no. 5. Soto del Real: Centro de Investigaci on

Fernando Gonz alez Bern aldez.

G omez-Lim on, J., M ugica, M., Medina, L., & De Lucio, J.V. (1994).

Areas recreativas en la Comu-

nidad de Madrid. Auencia de visitantes y actividades desarrolladas [Picnic areas in the ARM.

Inux of visitors and performed activities], Series document no. 14. Soto del Real: Centro de

Investigaci on Fernando Gonz alez Bern aldez.

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

4

6

.

8

3

.

2

0

7

.

4

]

a

t

1

4

:

2

2

2

1

M

a

r

c

h

2

0

1

3

1024 D. Rodrguez-Rodrguez

G omez-Lim on, J., M ugica, M., Mu noz, C., & De Lucio, J.V. (1996). Uso recreativo de los espa-

cios naturales en Madrid. Frecuentaci on, caracterizaci on de visitantes e impactos ambientales

[Recreational use of protected areas in Madrid. Attendance, visitors characterization and envi-

ronmental impacts], Series document no. 19. Soto del Real: Centro de Investigaci on Fernando

Gonz alez Bern aldez.

Hillery, M., Nancarrow, B., Grifn, G., & Syme, G. (2001). Tourist perception of environmental

impact. Annals of Tourism Research, 28, 853867.

Hunter, C., & Green, H. (1995). Tourism and the environment. A sustainable relationship? London:

Routledge.

Instituto Nacional de Estadstica (INE). 2011. Demografa y poblaci on. Cifras de poblaci on y censos

demogr acos. Retrieved from http://www.ine.es/inebmenu/mnu_cifraspob.htm

Kaseva, M.E., & Moirana, J.L. (2010). Problems of solid waste management on Mount Kilimanjaro:

A challenge to tourism. Waste Management & Research, 28, 695704.

Leung, Y.F., & Marion, J.L. (1999). Assessing trail conditions in protected areas: Application of

a problem-assessment method in Great Smoky Mountains National Park, USA. Environmental

Conservation, 26, 270279.

Liddle, M. (1997). Recreation ecology. London: Chapman & Hall.

Mc Kercher, B., &Weber, K. (2008). Rationalising inappropriate behaviour at contested sites. Journal

of Sustainable Tourism, 16(4), 369385.

M ugica, M. (1994). Modelo de demanda paisajstica y uso recreativo de los espacios naturales [A

model for landscape demand and recreational use of protected areas], Series document no. 16.

Soto del Real: Centro de Investigaci on Fernando Gonz alez Bern aldez.

Mulero, A. (2002). La protecci on de espacios naturales en Espa na. Antecedentes, contrastes territo-

riales, conictos y perspectivas [The protection of natural areas in Spain. Background, territorial

biases, conicts and prospects]. Madrid: Mundi-Prensa.

Naredo, J.M., & Fras, J. (2005). Desarrollo: La sntesis del desarrollo sostenible con especial

referencia a la Comunidad de Madrid. [Development: The synthesis of sustainable development

referred to the ARM]. In F. S anchez-Herrera (Ed.), Cuartas Jornadas Cientcas del Parque

Natural de Pe nalara y del Valle de El Paular. Conservaci on y desarrollo socioecon omico en

Espacios Naturales Protegidos [Fourth Scientic Meeting of the Pe nalara Natural Park and El

Paular Valley. Conservation and socioeconomic development in protected areas] (pp. 738).

Madrid: Consejera de Medio Ambiente y Ordenaci on del Territorio, Comunidad de Madrid.

Newsome, D., Moore, S. & Dowling, R. (2002). Natural area tourism. Ecology, impacts and man-

agement. Clevedon: Channel View Publications.

Rodrguez-Rodrguez, D. (2008). Los espacios naturales protegidos de la Comunidad de Madrid.

Principales amenazas para su conservaci on [The protected areas of the ARM. Main threats to

their conservation]. Madrid: Editorial Complutense.

Rodrguez-Rodrguez, D. (2009). Mitigaci on de los impactos del turismo en espacios naturales pro-

tegidos y mejora de su nanciaci on a trav es de medidas econ omicas. El caso de la Comunidad de

Madrid [Mitigation of the impacts fromtourismin protected areas and their nancial enhancement

by economic measures. The case of the ARM]. Boletn de la A.G.E., 50, 217238.

Tisdell, C. (2001). Tourism economics, the environment and development. Analysis and policy. Chel-

tenham: Edward Elgar.

Vacas, A.M. (2006). Sensibilizaci on para la conservaci on del paisaje (I): Recursos culturales y

equipamientos de uso p ublico en la Sierra de Guadarrama (Madrid) [Public awareness for land-

scape conservation (I): cultural resources and public use infrastructure in the Guadarrama moun-

tains (Madrid)], Series document no. 46. Soto del Real: Centro de Investigaci on Fernando

Gonz alez Bern aldez.

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

1

4

6

.

8

3

.

2

0

7

.

4

]

a

t

1

4

:

2

2

2

1

M

a

r

c

h

2

0

1

3

Вам также может понравиться

- Pike, Bianchi, Kerr & Patti - Consumers-Based Brand Equity For Australia As A Long Haul Tourism Destination in An Emerging MarketДокумент27 страницPike, Bianchi, Kerr & Patti - Consumers-Based Brand Equity For Australia As A Long Haul Tourism Destination in An Emerging MarketGerson Godoy RiquelmeОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Pomering, Noble & Johnson - Coceptualising A Contemporary Marketing Mix For Sustainable TourismДокумент18 страницPomering, Noble & Johnson - Coceptualising A Contemporary Marketing Mix For Sustainable TourismGerson Godoy RiquelmeОценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Pike & Mason - Destination Competitiveness Through The Lens of Brand Positioning - The Case of Australia's Sunshine CoastДокумент26 страницPike & Mason - Destination Competitiveness Through The Lens of Brand Positioning - The Case of Australia's Sunshine CoastGerson Godoy RiquelmeОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Robertson Roland - Globalisatio or GlocalisationДокумент22 страницыRobertson Roland - Globalisatio or GlocalisationGerson Godoy RiquelmeОценок пока нет

- Anatolia: An International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality ResearchДокумент23 страницыAnatolia: An International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality ResearchGerson Godoy RiquelmeОценок пока нет

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Tosun Cevat - Towards A Typology of Community Participation in The Tourism Development Process PDFДокумент24 страницыTosun Cevat - Towards A Typology of Community Participation in The Tourism Development Process PDFGerson Godoy RiquelmeОценок пока нет

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Tosun Cevat - Expected Nature of Community Participation in Tourism Development PDFДокумент12 страницTosun Cevat - Expected Nature of Community Participation in Tourism Development PDFGerson Godoy Riquelme0% (1)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Bramwell & Lane - Sustainable Tourism - An Evolving Global ApproachДокумент6 страницBramwell & Lane - Sustainable Tourism - An Evolving Global ApproachGerson Godoy Riquelme100% (1)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Von Der Weppen & Cochrane - Social Enterprises in Tourism - An Exploratory Study of Operational Models SND Success Factors PDFДокумент16 страницVon Der Weppen & Cochrane - Social Enterprises in Tourism - An Exploratory Study of Operational Models SND Success Factors PDFGerson Godoy RiquelmeОценок пока нет

- Weaver David - Indigenous Tourism Stages and Their Implications For Sustainability PDFДокумент18 страницWeaver David - Indigenous Tourism Stages and Their Implications For Sustainability PDFGerson Godoy RiquelmeОценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Oliveira & Telhado - Who Values What in A Tourism Destination - The Case of Madeira Island PDFДокумент14 страницOliveira & Telhado - Who Values What in A Tourism Destination - The Case of Madeira Island PDFGerson Godoy RiquelmeОценок пока нет

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Bourdeau Philippe - Mountain Tourism in A Climate of ChangeДокумент14 страницBourdeau Philippe - Mountain Tourism in A Climate of ChangeGerson Godoy RiquelmeОценок пока нет

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Almeida, Silva, Mendes & Oom - The Effects of Marketing Communication On The Tourist's Hotel Reservation ProcessДокумент18 страницAlmeida, Silva, Mendes & Oom - The Effects of Marketing Communication On The Tourist's Hotel Reservation ProcessGerson Godoy RiquelmeОценок пока нет

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- RДокумент17 страницRduongpndngОценок пока нет

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- Solid Desiccant DehydrationДокумент5 страницSolid Desiccant Dehydrationca_minoОценок пока нет

- Suzuki G13ba EnginДокумент4 страницыSuzuki G13ba EnginYoga A. Wicaksono0% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Antony Kungu - Final Project AssignmentДокумент11 страницAntony Kungu - Final Project Assignmentapi-420816837Оценок пока нет

- CadДокумент20 страницCadVivek DesaleОценок пока нет

- 563000-1 Web Chapter 4Документ22 страницы563000-1 Web Chapter 4Engr Ahmad MarwatОценок пока нет

- STP Tender Document For 08.05.2018Документ32 страницыSTP Tender Document For 08.05.2018Arunprasad DurairajОценок пока нет

- Procedimiento de Test & Pruebas Hidrostaticas M40339-Ppu-R10 HCL / Dosing Pumps Rev.0Документ13 страницProcedimiento de Test & Pruebas Hidrostaticas M40339-Ppu-R10 HCL / Dosing Pumps Rev.0José Angel TorrealbaОценок пока нет

- BDM DriverДокумент16 страницBDM DrivervolvodiagОценок пока нет

- Ultrasonic Levndsgjalshfgkdjakel Endress Hauser Fmu 40 Manual BookДокумент84 страницыUltrasonic Levndsgjalshfgkdjakel Endress Hauser Fmu 40 Manual BookrancidОценок пока нет

- ASW Connection PDFДокумент7 страницASW Connection PDFWawan SatiawanОценок пока нет

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- 2006 AcrotechДокумент32 страницы2006 Acrotechkaniappan sakthivelОценок пока нет

- R10 On XPДокумент182 страницыR10 On XPadenihun Adegbite100% (1)

- ACC Flow Chart (Whole Plan) - Rev00Документ20 страницACC Flow Chart (Whole Plan) - Rev00amandeep12345Оценок пока нет

- Wyche Bridge 2000Документ12 страницWyche Bridge 2000BhushanRajОценок пока нет

- Plastiment BV 40: Water-Reducing Plasticiser For High Mechanical StrengthДокумент3 страницыPlastiment BV 40: Water-Reducing Plasticiser For High Mechanical StrengthacarisimovicОценок пока нет

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- J416V06 enДокумент4 страницыJ416V06 enMartin KratkyОценок пока нет

- ACCY225 Tri 1 2017 Tutorial 3 Business Processes-2Документ3 страницыACCY225 Tri 1 2017 Tutorial 3 Business Processes-2henryОценок пока нет

- DCTN Lsqmdocu63774Документ21 страницаDCTN Lsqmdocu63774Bharani KumarОценок пока нет

- UD05674B Baseline Access Control Terminal DS-KIT802 User Manual V2.0 20180228Документ121 страницаUD05674B Baseline Access Control Terminal DS-KIT802 User Manual V2.0 20180228iresh jayasingheОценок пока нет

- RRLДокумент3 страницыRRLNeil RosalesОценок пока нет

- Sell Sheet Full - Size-FinalДокумент2 страницыSell Sheet Full - Size-FinalTito BustamanteОценок пока нет

- Advanced Plate Fin Heat Sink Calculator - MyHeatSinksДокумент2 страницыAdvanced Plate Fin Heat Sink Calculator - MyHeatSinksHarsh BhardwajОценок пока нет

- Manual Redutores SEWДокумент154 страницыManual Redutores SEWLucas Issamu Nakasone PauloОценок пока нет

- 5th Kannada EvsДокумент256 страниц5th Kannada EvsnalinagcОценок пока нет

- Man Ssa Ug en 0698Документ43 страницыMan Ssa Ug en 0698Andy LОценок пока нет

- Ooad Question BankДокумент5 страницOoad Question Bankkhusboo_bhattОценок пока нет

- Econ Ball Valves Stainless Steel 3 Way Port: Blow-Out Proof StemДокумент1 страницаEcon Ball Valves Stainless Steel 3 Way Port: Blow-Out Proof StemChristianGuerreroОценок пока нет

- MSC BMT Excel Spreadsheet For Salmon FisheriesДокумент10 страницMSC BMT Excel Spreadsheet For Salmon FisheriesYamith.8210hotmail.com PedrozaОценок пока нет

- Fw102 User ManuleДокумент12 страницFw102 User ManulerobОценок пока нет