Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Urban Stud 2013 Kovбcs 22 38

Загружено:

Rossi DelchevАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Urban Stud 2013 Kovбcs 22 38

Загружено:

Rossi DelchevАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

http://usj.sagepub.

com/

Urban Studies

http://usj.sagepub.com/content/50/1/22

The online version of this article can be found at:

DOI: 10.1177/0042098012453856

2013 50: 22 originally published online 13 August 2012 Urban Stud

Zoltn Kovcs, Reinhard Wiessner and Romy Zischner

Perspective

Urban Renewal in the Inner City of Budapest: Gentrification from a Post-socialist

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

Urban Studies Journal Foundation

can be found at: Urban Studies Additional services and information for

http://usj.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Email Alerts:

http://usj.sagepub.com/subscriptions Subscriptions:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Reprints:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Permissions:

What is This?

- Aug 13, 2012 OnlineFirst Version of Record

- Dec 17, 2012 Version of Record >>

by guest on October 30, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from by guest on October 30, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Urban Renewal in the Inner City of

Budapest: Gentrification from a Post-

socialist Perspective

Zoltan Kovacs, Reinhard Wiessner and Romy Zischner

[Paper first received, August 2011; in final form, April 2012]

Abstract

After the political and economic changes of 198990, the concept of gentrification

inspired many urban researchers in central and eastern Europe (CEE). Despite the

growing number of papers, there is still a substantial empirical gap concerning the

transformation of inner-city neighbourhoods in the CEE. This paper is based on

empirical data regarding the physical and social upgrading of neighbourhoods in

inner Budapest. The paper argues that gentrification in its traditional sense affects

only smaller areas of the inner city, mostly those where demolition and new housing

construction took place as an outcome of regeneration programmes. At the same

time, the old housing stock has been less affected by gentrification. This is mainly

due to the high share of owner-occupation and the social responsibility of local gov-

ernments. Thanks to renovation and new housing construction, a healthy social mix

will probably persist in the inner city of Budapest in the future.

1. Introduction

The concept of gentrification has domi-

nated the literature dealing with inner-city

transformations over the past four decades

(Clark, 1991; Lees, 2008; Lees et al., 2008;

Ley, 1981; Smith, 1979, 1996). After the

political and economic changes of 198990,

the concept has also gained more attention

in urban research in central and eastern

Europe (CEE) (Kova cs, 1998, 2009; Standl

and Krupickaite, 2004; Sy kora, 1999, 2005;

Foldi, 2006). This is mainly because the

cities of CEE were affected by rapid eco-

nomic restructuring and social change as an

outcome of the post-communist transition

Zoltan Kovacs is in the Institute of Geography, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budao rsi ut 45,

Budapest, H-1112, Hungary. E-mail: zkovacs@mail.iif.hu.

Reinhard Wiessner and Romy Zischner are in the Institute of Geography, University of Leipzig,

Johannisallee 19a, 04103 Leipzig, Germany. E-mail: wiessner@rz.uni-leipzig.de and zischner@

rz.uni-leipzig.de.

Urban Studies at 50

50(1) 2238, January 2013

0042-0980 Print/1360-063X Online

2012 Urban Studies Journal Limited

DOI: 10.1177/0042098012453856

by guest on October 30, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

and their internal socioeconomic patterns

tended to resemble the west European cities

(Boren and Gentile, 2007; Sy kora, 2009).

The massive inflow of global capital resulted

in new shopping, office and leisure centres

in inner-city and suburban locations. New

residential quarters for the better off in the

form of single-family housing and gated

communities were developed at the edge of

the compact city and more often in the sub-

urbs (Andrusz et al., 1996; Enyedi, 1998;

Leetmaa and Tammaru, 2007; Ourednicek,

2007; Ruoppila and Kahrik, 2003).

Nevertheless, the development of inner-

city neighbourhoods did not initially follow

the West European pattern. The social and

physical upgrading of these neighbourhoods

(i.e. gentrification) remained limited and

brought about only small and sporadic

developments during the 1990s (Haase

et al., 2012; Kova cs, 1998; Sy kora, 2005). In

most parts of the inner cities, a relative

decline remained prevalent after 1990 due

to worsening housing and environmental

conditions, the continuing concentration of

people with lower income and the lack of

legal and planning frameworks supporting

regeneration. In some cases, inner-city

neighbourhoods even became hotbeds of

social exclusion and segregation in the

first decade of transition (Lada nyi, 2002;

Wec1awowicz, 2002). Perhaps the only

exception within the wider region was

Eastern Germany where large-area regenera-

tion programmes with massive central-state

support resulted in spectacular upgrading

processes in the inner cities as early as the

mid 1990s (Brade et al., 2009).

However, a growing body of literature

has indicated a turnaround in the develop-

ment of post-socialist inner cities recently.

Signs of physical upgrading coupled with

gentrification have been reported from sev-

eral CEE cities even though most of these

studies focused on capital cities where

systemic transformations and globalisation

processes have been most advanced,

like Prague (Cook, 2010; Sy kora, 2005;

Temelova , 2007), Moscow (Badyina and

Golubchikov, 2005; Gritsai, 1997), Vilnius

(Standl and Krupickaite, 2004) or Budapest

(Foldi, 2006; Kova cs, 2009). Most of the

literature to date, however, lacks a convin-

cing empirical underpinning as far as the

mechanisms of gentrification, its actors and

outcomes are concerned. Therefore, it is

difficult to assess to what extent neighbour-

hood upgrading processes in post-socialist

cities fit the wider concept of gentrification

elaborated in western Europe and North

America. To narrow the gap, this paper

focuses on the socio-spatial change that has

taken place in the inner city of Budapest

from an empirical perspective. Based on

empirical research findings we try to

answer the following questions

What are the main factors of neighbour-

hood change and what is the role of local

policy in the regeneration of inner-city

neighbourhoods in Budapest?

How does residential change (displace-

ment) take place as a result of regenera-

tion and how has the socio-demographic

profile of upgraded neighbourhoods

changed?

Can we call this process gentrification in

a Western sense? What are the similari-

ties and differences between the Budapest

findings and processes described in the

Western literature?

Before introducing the empirical results and

answering these questions, we briefly reflect

on the theoretical background and intro-

duce the local framework conditions. After

the empirical analysis, we would like to turn

back to the original concept of gentrification

and fit the observed processes into a wider

conceptual framework.

URBAN RENEWAL IN BUDAPEST 23

by guest on October 30, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

2. The Concept of Gentrification

and its Post-socialist Interpretations

The term gentrification has been used in the

literature in many different ways and the cri-

tique of a chaotic concept is more than ever

timely (Beauregard, 1986). If we take the tra-

ditional concept of gentrification put for-

ward by Ruth Glass (1964), it refers to the

process of transformation of old residential

neighbourhoods in which working-class and

poor residents are displaced by an influx of

gentrifiers, a new class consisting of well-

educated and better-off people. This change

results in improvements in the areas hous-

ing stock and public infrastructure with a

concomitant increase in dwelling prices and

rents (Hammel, 2009).

Over the past four decades, there has

been a shift in meaning and, in contrast to

the traditional definition, recent concepts of

gentrification apply a much broader view.

Terms like rural gentrification (Phillips,

1993), new-build gentrification (Davidson

and Lees, 2010; Rerat and Lees, 2011) super

gentrification (Hammel, 2009) broadened

the view of gentrification and covered a

huge variety of social transformation pro-

cesses in and outside the inner cities (Lees

et al., 2008).Writing about gentrification,

some authors put the emphasis on physical

upgrading which is not necessarily followed

(or just to a limited extent) by an influx of

better-off people and an increase in real

estate prices. As a contrast, others use the

term of gentrification exclusively for social

upgrading processes and, according to their

view, a physical upgrading in the gentrifica-

tion is not necessary (Friedrichs, 1996;

Glatter, 2007).

As we can see, very different processes are

interpreted in the literature as gentrification

that do not correspond to the traditional

recipe of the phenomenon. This reflects the

gradual change that has evolved in gentrifi-

cation research as far as the forms, actors

and geographical locations of the process

are concerned. As a consequence, gentrifica-

tion has gradually become a catch-all term

used to describe a great variety of social and

physical urban transformation processes

(Atkinson and Bridge, 2005; Lees et al.,

2008; Rerat et al., 2010). This is not least

because our cities are affected by many dif-

ferent types of physical and social upgrad-

ings, resulting from commercialisation,

globalisation and the growing differentia-

tion of lifestyle and housing preferences of

residents, underpinned by specific frame-

work conditions at the national and local

levels. The classical notion of gentrification

is therefore only one of the variants of the

term today. However, the use of the broad

concept of gentrification can result in the

original content of the process referring to

qualitative changes in an urban neighbour-

hood getting lost. In our empirical analysis,

we use the more focused term of regenera-

tion when selecting and analysing the case

study areas. By this term, we mean in general

the physical renewal and social upgrading of

old run-down residential neighbourhoods.

The physical and social upgrading of

inner-city neighbourhoods show great var-

iations in the post-socialist countries as

well. Cities of early reforming countries (the

Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland) and East

Germany, where inner-city restructuring

had already started in the early 1990s pro-

vide showcases for gentrification, whereas

reports on gentrification from latecomer

countries in the CEE are very rare (for

example, Chelcea, 2006). Physical upgrad-

ing of inner-city neighbourhoods first

became evident in the East German cities

where the regeneration of old residential

buildings has been significantly supported

by the central state (Bernt and Holm, 2005;

Glatter, 2007; Weiske, 1996). In these cities,

rents remained on a rather low level; conse-

quently, lower-income groups (for example,

students) continued to have access to the

24 ZOLTA

N KOVA

CS ET AL.

by guest on October 30, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

renovated dwellings and a radical displace-

ment of local population could not evolve.

Therefore, this process was labelled in the

literature as soft gentrification or con-

trolled gentrification (Wiest and Zischner,

2006).

Analysing the urban restructuring of

Hungarian cities, several studies had already

revealed by the 1990s that the basic precon-

dition for the gentrification process was the

mass privatisation of housing and the sky-

rocketing value gap in the old inner-city

neighbourhoods (Beluszky and Tima r,

1992; Kova cs, 1994). In these neighbour-

hoods, displacement of the sitting residents

took place with the active participation of

the local governments initiating local regen-

eration programmes; thus, the process was

labelled as organised gentrification (Boros

et al., 2010; Foldi, 2006; Janko , 2012;

Kova cs, 2009; Nagy and Tima r, 2012). The

role of neo-liberal urban policy was also

emphasised by Standl and Krupickaite

(2004) in Vilnius, where the Old Town

Revitalisation Programme launched in 1998

created favourable conditions in the inner-

city quarter of Uzupis for physical upgrad-

ing and a subsequent population change.

Gentrification in Uzupis was initiated by

artists at the end of 1990s (pioneer phase),

followed by the influx of better-off middle-

class families in the early 2000s.

Haase et al. (2012) found during their

on-site-research in two second-order post-

socialist cities, qo dz (Poland) and Brno

(Czech Republic), that displacement of

sitting residents did not occur in the inves-

tigated inner cities; however, they also

pointed out that the in-migration of

younger households, professionals and

students in these neighbourhoods intensi-

fied recently what could be the indication

of a forthcoming gentrification. They

called the group of new residents transi-

tory urbanites (Haase et al., 2012). In the

same vein, Marcinczak and Sagan (2011)

confirm that revitalisation and socio-

demographic change remained limited in

the inner city of qo dz (Poland) and con-

centrated only on buildings with clarified

property rights, good locations adjacent

to the main street and attractive architec-

ture. The authors labelled the sporadic

signs of upgrading in the inner city as

fac xade gentrification. Gentrification is

even more ambiguous in the capital city

of Romania. Chelcea (2006) argued that

informal and in many cases illegal transfer

of property rights is a key factor of gentri-

fication in downtown Bucharest, leading

to eviction and primitive accumulation.

Given the Janus face of gentrification

with strong local characteristics, some

scholars in the CEE are not even inclined

to apply the concept of gentrification to

post-socialist inner-city transformations

(for example, Haase et al., 2012; Sy kora,

2005). At the end of this paper, we turn

back to the issue of whether or not neigh-

bourhood change that has taken place in

downtown Budapest fits in with the tradi-

tional concept of gentrification.

3. The Framework Conditions of

Urban Renewal in the Inner City of

Budapest

The development of inner-city neighbour-

hoods in Budapest was substantially influ-

enced by the specific conditions that were

created by the post-communist transforma-

tion after 1990. Perhaps the two most

important factors with regards to urban

renewal were the reshuffle of the public

administration system and the transforma-

tion of the housing market.

In 1990, the return to self-governance in

Budapest also meant the introduction of a

two-tier administrative system and the sub-

sequent shift of power from city to district

level. The competence of districts was

URBAN RENEWAL IN BUDAPEST 25

by guest on October 30, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

significantly strengthened. They enjoy a high

level of autonomy in implementing housing

and social policies, launching regeneration

programmes, drawing regulations plans, etc.

On the one hand, this political fragmenta-

tion of the city set up serious barriers as far

as the elaboration and implementation of

comprehensive urban development pro-

grammes are concerned, but on the other

hand, it also provided the districts with the

opportunity to try out and implement small,

area-based interventions. Indeed, the inner

city of Budapest became an urban laboratory

where numerous small, neighbourhood

initiatives have been experimented with

since the change of political system, resulting

in various forms of physical upgrading and

social change.

As Sy kora (2005) pointed out, with

regard to gentrification in post-socialist

cities, the most influential factors were

housing privatisation and rent deregulation.

In the case of Budapest, rent deregulation

did not have too much influence because of

the negligible role of the private rental

sector. However, the privatisation of the

public housing sector was pivotal in the

restructuring of inner-city neighbourhoods

(Hegedus and Tosics, 1994). In Budapest,

the privatisation of public housing meant a

give-away privatisation to sitting tenants at

a very low price. This practice, in addition

to no restrictions on resale of the dwelling,

made the privatisation of public dwellings

very attractive, especially those of better

quality and with more desirable locations

(Kova cs, 2009). However, there were at least

two negative effects of this practice of priva-

tisation. On the one hand, dwellings of sub-

standard quality often remained in public

ownership and the public housing sector

became gradually residualised. On the other

hand, since individual housing units were

sold to the tenants on a right-to-buy basis,

the outcome was very often mixed owner-

ship within the tenement buildings. This

made any kind of renovation in the build-

ings extremely difficult.

We can also say that in the first half of the

1990s both the legal and the planning frame-

works of urban regeneration were missing in

Budapest (Egedy, 2010). In addition, the

new local governments lacked the necessary

resourcesjust like the new owners of the

privatised dwelling stockto undertake

renovations, whereas the private sector had

hardly any interest in the renewal of residen-

tial buildings. From the mid 1990s, the legal,

planning and financial framework of urban

regeneration was gradually elaborated. In

1994, the Act on Condominiums solved the

problem of blocks of flats with mixed tenure,

giving them a firm legal status. In 1996, the

official urban regeneration programme of

Budapest was elaborated by the Budapest

municipality. From the late 1990s, financial

resources from other national programmes

(such as the social housing development pro-

gramme) could be used in urban regenera-

tion and, finally, after 2000 the private sector

also started to show growing interest in the

redevelopment of certain centrally located

inner-city neighbourhoods. These develop-

ments together led to the proliferation of

regeneration activities in the inner city of

Budapest after the turn of millennium.

4. Physical and Social Upgrading

in the Inner City of Budapest

after 1990

4.1 Research design

The following analysis is based on empirical

data collected in an international research

project focusing on the physical and social

transformation of the inner city of Budapest.

The main objective of the project was to

record the architectural and social aspects of

neighbourhood change in a comprehensive

manner and with regard to the existing

26 ZOLTA

N KOVA

CS ET AL.

by guest on October 30, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

concepts of gentrification. In addition to

empirical surveys, interviews with experts

were carried out to collect information

about the strategies and interests of different

actors (local government, investors, resi-

dents) in the process of neighbourhood

regeneration.

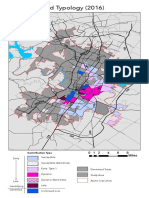

In July 2005, a mapping survey in inner

Budapest was performed (see Figure 1),

where the most important physical and

functional parameters of the building stock

were recorded. The survey covered 10 534

buildings of various types. This survey

enabled us to identify the intensity of dilap-

idation or renovation at the level of build-

ings, blocks and neighbourhoods.

Based on the results of our mapping

survey, seven smaller neighbourhoods were

Figure 1. The areas of investigation in the inner city of Budapest.

URBAN RENEWAL IN BUDAPEST 27

by guest on October 30, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

identified where either signs of intense phys-

ical upgrading or functional changes hinting

at the presence of gentrification could be

observed. In these neighbourhoods, what we

may call core areas of regeneration, a

detailed questionnaire survey was carried

out among residents in 2006, focusing on

the renewal activities of households, their

residential mobility and housing prefer-

ences. In the seven neighbourhoods, 1234

households were randomly selected for the

survey out of which 503 were successfully

completed (41 per cent). To fine tune the

results of the questionnaire survey, in-depth

interviews with selected households were

also carried out to gather information about

the mobility and lifestyle of different house-

hold types.

4.2 Patterns of Physical Upgrading

Renewal of buildings. In the mapping

survey, visible signs of renovation and new

developments were recorded (the quality of

the fac xade, new window frames, etc.) for

each building. Table 1 summarises the

extent of renewal of residential buildings in

the survey area. For the sake of analysis, we

refer here only to data for buildings which

have a predominantly (over 50 per cent)

residential use. According to our survey, 6

per cent of the buildings were built and a

further 28 per cent have been fully reno-

vated in inner Budapest after 1990. This

means that about one-third of the building

stock was affected by some kind of physical

renewal in the post-communist era. If we

also add those cases where the fac xade was

completely renovated (major renewal),

the intensity of renewal activity is over 40

per cent in the entire inner city.

Analysing the spatial pattern of regenera-

tion, concentrations of high- and low-level

renovations can be identified (Figure 2).

Upgraded areas indicated on the map can

be classified into two groups.

On the one hand, there are traditional

high-status areas of the city centre (CBD)

where the value gap is highest. These neigh-

bourhoods were affected mostly by sponta-

neous (market-led) renewal, where the main

actors have been local residents, as well as

foreigners. According to real estate experts,

the emergence of a considerable demand

from foreign citizens in the local housing

market dates back to Hungarys accession to

the European Union (2004). As a result of

the unlimited right of EU citizens to obtain

property, the Spanish, British and Irish were

the first to invest massively in housing in the

inner-city quarters of Budapest. To this

group of foreigners, we should also add

Table 1. The intensity of revitalisation of residential buildings in the survey area, 2005

Physical renewal of residential buildings (fac xade and windows) Valid cases Percentage

New construction Built after 1990 482 6

Full renewal Fac xade and windows completely renovated 2393 28

Major renewal Fac xade completely, windows partly renovated 568 7

Partial renewal Fac xade not, but windows are renovated 2882 33

or

Windows not, but fac xades are renovated

Limited renewal No renovation on fac xade, windows partly renovated 961 11

No renewal No signs of renovation of fac xade or windows 1429 16

Total 8715 100

Source: mapping survey, 2005.

28 ZOLTA

N KOVA

CS ET AL.

by guest on October 30, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

expats and well-paid professionals of trans-

national firms working in the city centre

who prefer to live close to their workplace

(Foldi and Van Weesep, 2007).

On the other hand, an extensive upgrad-

ing process has taken place beyond the arc

of the Grand Boulevard, in certain parts of

Ferencva ros (district IX) and to a lesser

extent in Jo zsefva ros (district VIII). In

these originally working-class neighbour-

hoods, the main reason for the upgrade

was the implementation of state-led regen-

eration programmes in the 1990s. The ear-

liest and perhaps most successful urban

regeneration programme in Budapest was

launched in Middle Ferencva ros in 1992.

It was designed according to the French

SEM model (Societe dE

conomie Mixte) as

a publicprivate partnership (PPP) set up

by local government (with 51 per cent of

the shares) and a HungarianFrench con-

sortium of investors. In a similar vein,

Jo zsefva ros (district VIII) started to imple-

ment its regeneration policy in 1998 and

set up a share-holding company called

Rev8 to organise urban renewal in a spe-

cially designated area of the district.

However, there are also distinct areas in

the inner city of Budapest where no or

hardly any sign of renovation could be

identified over the past two decades. These

are typically old working-class neighbour-

hoods with multistorey tenement blocks in

the eastern periphery of the inner cityfor

example, Erzsebetva ros (district VII).

The level of renovation also shows

marked variations among our case study

areas. The ratio of newly built, or since

1989 completely or largely renovated, resi-

dential buildings was clearly the highest in

the SEM IX area (77.8 per cent), whereas in

the Theatre Quarter only one-fifth of the

building stock fell into this category. We

assume that higher levels of regeneration

would also entail higher levels of popula-

tion displacement (i.e. gentrification) in the

case study areas.

Housing tenure and renewal of

dwellings. Our questionnaire survey shed

Figure 2. The spatial pattern of residential renewal in the inner city of Budapest.

URBAN RENEWAL IN BUDAPEST 29

by guest on October 30, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

light on the age, tenure and quality of

housing in the case study areas. The over-

whelming majority (83 per cent) of the

housing stock was built before the political

changes, and even before World War I.

However, the 17 per cent share of new

housing constructed after the change of

regime is also considerable. We can also

add that a disproportionately large number

of newly constructed dwellings were com-

pleted after 2000.

Our survey showed that owner-

occupation is the dominant tenure type

both in the old and new housing stock.

Altogether, 80 per cent of the dwelling

stock is owned and inhabited by private

persons in the case study areas. A typical

post-socialist phenomenon is the high

share (43 per cent) of households who

acquired their apartment in the process of

privatisation. With regard to the rental

sector, we can observe a balance between

the private and public rental sectors (10 per

cent each), which is the logical outcome of

privatisation, on the one hand, and the

development of a market-based rental

sector since the political changes.

The dynamics of the local housing market

are reconstructed in Figure 3. As shown, two

peaks of housing transactions can be distin-

guished in the post-communist period. The

first boom can be linked with the privatisa-

tion of the public housing sector at the begin-

ning of the 1990s; while the second boom

evolved in the early 2000s and was generated

by the secondary transactions of old dwell-

ings and the sales of newly built ones.

In two case study areas, the regeneration

process could be attributed predominantly

to new construction: in the Rev8 area in dis-

trict VIII and in the SEM IX area in district

IX. Both areas belonged to the most dilapi-

dated inner-city slums of Budapest before the

political changes, that became targets of state-

led regeneration programmes in the 1990s.

The newly built dwellings in these neighbour-

hoods are in general 4080 square metres in

floor area, with high levels of comfort, attrac-

tive typically for younger households but not

so much for the wealthiest sections of society

(Berenyi and Szabo , 2009).

Since 1989, the renewal of the old dwell-

ing stock has also intensified in the surveyed

areas. Our results demonstrate that a

Figure 3. Housing transactions in the core areas of revitalisation.

30 ZOLTA

N KOVA

CS ET AL.

by guest on October 30, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

significant part of the old housing stock has

been largely (30 per cent) or partially (59

per cent) renovated since 1989. This also

hints at the strong presence of incumbent

upgrading. Only 11 per cent of the old hous-

ing stock has not been affected by any kind

of renovation or just to a very limited

extent. The level of renovation is generally

the highest in that segment of the owner-

occupied housing stock that was obtained

by purchase in the free market. At the same

time, the level of renovation is significantly

lower in the residual public housing sector.

The role of local policies in urban

regeneration. The chances of regenera-

tion as well as its actual level depend very

much on the local policies of districts in

the inner city of Budapest (Foldi, 2006). In

this respect, the size of local public housing

stock, the quantity of available vacant plots

and brownfield sites where the local govern-

ment could initiate new housing projects,

just like the geographical location of the

quarter and its architectural quality, have

played an important role. On the basis of

interviews with local experts, we could iden-

tify three distinct groups among the districts

according to the local regeneration strategies.

An active strategy for urban regenera-

tion. We can find active urban regeneration

strategies in two districtsFerencva ros

(district IX) and Jo zsefva ros (district VIII).

These two districts were among the first to

formulate clear strategies for the regenera-

tion of their run-down neighbourhoods and

set into motion large area-based regenera-

tion programmes during the 1990s, provid-

ing a laboratory and also best practices for

Budapest and beyond. In both districts, a

large part of the public housing stock

remained in state (district) ownership pro-

viding local government with more room

for intervention. In addition, both districts

were rich in vacant plots which made large-

scale regeneration easier. These two districts

established special regeneration companies

on a PPP basis in the 1990s that took

responsibility for and co-ordinated the pro-

cess of urban renewal.

A limited support for urban regenera-

tion strategy. In other districts, the

regeneration/renewal process was less sys-

tematically organised; nevertheless, it has

been in one way or another supported by

the local government. A good example is

the Theatre Quarter (district VI) where

the upgrading was enhanced by local infra-

structure development (reconstruction of

street surfaces and the development of

pedestrian zones) and the promotion of

local cultural institutions in order to

increase the attractiveness of the neigh-

bourhood. In Middle Terezva ros (district

VI) a public programme was launched for

the renovation and conversion of lofts.

Through the sale of unused attic areas in

blocks of flats for private investors, housing

condominiums could acquire a good income

that was used for the renovation of the rest

of the building. In the Bar Quarter in dis-

trict IX, the development of a bar and restau-

rant quarter was enhanced by the increasing

flow of tourists to Budapest and the growing

demand for catering facilities. The develop-

ment of the catering and tourism industry in

the neighbourhood brought about additional

investments in housing, whereas the local

government supported the upgrading of

public spaces, such as the renovation of road

surfaces, pedestrianisation. The aforemen-

tioned examples are located typically in

neighbourhoods with better-quality housing

and the renewal of buildings is performed by

individual condominiums.

A hands off approach. The attitude of

other districts with regards to regeneration

URBAN RENEWAL IN BUDAPEST 31

by guest on October 30, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

is rather passive and relies very much on

the market. This fits well with the

Southern City Area in district V, where

retail and business development leading to

commercial gentrification is the main

priority of local government as opposed

to the renewal of residential buildings.

Despite its relatively good opportunity for

intervention, the attitude of district VII

(Erzsebetvaros) has also been characterised

by a hands-off approach. Our case study area

in this district was the Jewish Quarter. Local

government here followed a very liberal lais-

sez-faire urban policy and provided great

opportunities for investors. During the

1990s, the vacant sites gradually disappeared

in the neighbourhood; first they were built

up with office, and later with residential

buildings. By the early 2000s, hardly any

empty plots remained for new construction;

therefore, demolition of existing buildings

started. In this process, several buildings with

great architectural value were torn down and

subsequently the architectural milieu, just

like the social profile of the whole neighbour-

hood, changed dramatically.

4.3 Social Change and Population

Displacement

The results of our survey showed that long-

term residents in the meantime became

only a minority in the selected neighbour-

hoods, 42 per cent being in situ before

1989. New constructions, secondary trans-

actions and rented dwellings provided the

basis for population change in the inner

city of Budapest. This process clearly inten-

sified over time, as only 20 per cent of the

households moved to their present dwelling

between 1990 and 2000, and another 38 per

cent in the short period of 200006. The

increasing number of new arrivals and the

extremely low vacancy rates indicate the

growing speed of population change in the

investigated neighbourhoods.

However, the massive displacement of

long-term residents, so much criticised in

the Western gentrification literature, has

been limited in the inner city of Budapest.

More displacement occurred in the offi-

cially designated areas of urban regenera-

tion where exensive demolitions also took

place. In the SEMIX area, some 70 per cent

of residentsand in the Rev8 area, 44 per

centmoved to their current dwelling

between 2000 and 2006. Tenants of public

dwellings could be displaced in two differ-

ent ways: either the district government

offered the tenants three possible rental

choices (not always in the same district or

even in Budapest) and they had to choose

one of them; or, they were offered a cer-

tain amount of compensation money and

upon acceptance they had to resign their

tenants rights. The overall level of forced

displacement has been relatively low and it

was concentrated mainly in the areas of

state-led regeneration programmes (orga-

nised gentrification). In other areas, the

predominance of the owner-occupied

sector, the subordinated role of new con-

struction and the levelling-out policies of

local governments were able to prevent

massive displacement.

Like most of the authors on post-socialist

gentrification (Standl and Krupickaite,

2004; Kabisch et al., 2010; Marcinczak and

Sagan, 2011), we use socioeconomic indica-

tors to detect the directions of social trans-

formation in our neighbourhoods. First, we

concentrate on those households (38 per

cent) who moved to the area between 2000

and 2006. These households comprise

mainly young people, predominantly under

40 years of age. They are often single-person

households, young couples with or without

children, and flat-sharing communities,

which is otherwise uncommon in Budapest.

Many of them resemble, thus, the transi-

tory urbanites class described by Haase

et al. (2012).

32 ZOLTA

N KOVA

CS ET AL.

by guest on October 30, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

The income level of newcomers is defi-

nitely higher than the long-term residents.

The share of households with above-average

income is only 7 per cent among long-term

residents, whereas it is 24 per cent among

the newcomers. Similarly, the share of

households with below-average income is

much higher among the long-term resi-

dents (Figure 4).

Taking into account the level of educa-

tion, we found that the ratio of graduates is

significantly higher amongst recent arrivals;

the ratio of households with at least one

member holding a university or college

diploma is 51 per cent in the group of new-

comers and only 33 per cent among the

long-term households. Our data thus reflect

the process of rejuvenation and social

upgrading in the selected neighbourhoods.

However, we can also note that many of

the newcomersi.e. first-time buyers, who

have moved to the core areas of regenera-

tion recentlyhave relatively moderate

incomes. It means that access to the

Figure 4. Household composition according to the year of arrival and income level.

URBAN RENEWAL IN BUDAPEST 33

by guest on October 30, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

renovated neighbourhoods has been possi-

ble not only for higher-income groups, but

also for less affluent households. Since the

quality and size of the housing stock became

more heterogeneous in these neighbour-

hoods, partly because of renovations and

partly due to new construction, the socioeco-

nomic profile of local residents has also

become more mixed over the past two

decades.

The idea of creating more socially mixed

neighbourhoods has been high on govern-

mental agendas in the West (van Kempen

and Bolt, 2009); however, there has been

no sign of deliberate mixing policy in CEE

cities, yet. One of the unintended results of

the mushrooming of regeneration activities

in inner Budapest waswithout any delib-

erate policy backgroundsocially more

mixed communities. Recent critiques ques-

tion the positive effects of gentrification on

social mix, emphasising that gentrification

normally leads to social segregation, social

polarisation and displacement (Lees, 2008).

This is certainly true if gentrification takes

place in socially homogeneous low-income

areas. Yet the neighbourhoods we studied

were rather heterogeneous even before the

renewal activities, a path-dependent feature

of inner Budapest rooted in the communist

and even pre-communist periods. Critiques

are also made that, instead of the develop-

ment of social cohesion, gentrification can

create social tensionsespecially when

there are marked economic, social and cul-

tural differences between residents (Lees,

2008, p. 2456). This is not the case in

Budapest; at least, we could not find any

hard empirical evidence for local tensions

in our neighbourhoods.

Recent studies have also discussed the

connection between social mix and social

cohesion at the neighbourhood level (van

Kempen and Bolt, 2009; Musterd and

Andersson, 2005). The concept that better

social mix increases social cohesion has

been heavily criticised (Lees, 2008). Our

findingseven though measuring social

cohesion was not an explicit goal of our

surveyalso show that social interactions

were more intense and social networks

were more developed in neighbourhoods

where population change and social mixing

took place more slowly.

Taking into account the traditional class

categories in the gentrification literature,

we can confirm the presence of gentrifiers

in Budapest, especially in those neighbour-

hoods where the reconstruction of old and

the construction of new housing com-

menced hand-in-hand (new-build gentrifi-

cation). These are especially the SEMIX

and Rev8 areas among our neighbour-

hoods. Nevertheless, the group of pioneers

is much more dominant among the newco-

mers in the whole survey area. Whether

they constitute a transitory population

(transitory urbanites) who would be later

replaced by gentrifiers is more than doubt-

ful. The functioning of the local housing

market and the size of the owner-occupied

sector suggest that, despite intensifying

regeneration and subsequent population

change, the inner-city areas in Budapest

will retain a relatively heterogeneous popu-

lation in the future.

5. Conclusions

Regeneration of old inner-city neighbour-

hoods has been a spectacular phenomenon

in Budapest over the past two decades, with

regard to both its social and physical

dimensions. It is remarkable how neigh-

bourhoods that were affected by a dramatic

disinvestment and social decline during

communism have been undergoing gradual

social and physical upgrading due to

intense reinvestment. In this process, in

addition to the renovation of old buildings,

the construction of new residential enclaves

34 ZOLTA

N KOVA

CS ET AL.

by guest on October 30, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

has played an important role. As Neil

Smith (1996, p. 173) noted, Budapest pro-

vides a laboratory for examining the inter-

connected parries of supply and demand,

the impetus of production-side and

consumption-side forces in the genesis of

gentrification.

Research questions formulated in the

introductory section of this paper can be

answered in the following way. As our case

study neighbourhoods have shown, gentrifi-

cation is present in downtown Budapest in

many different ways ranging from commer-

cial gentrification and fac xade gentrification

to more traditional (Western) variants of

gentrification. Our results thus contradict

Sy koras previous findings, based on the lit-

erature of the 1990s, denying the presence

of true gentrification in inner Budapest

(Sy kora, 2005, p. 103).

The most relevant factors of neighbour-

hood change in the inner city of Budapest

can be summarised as follows

the capitalisation of the land and hous-

ing markets, a radical shift from public

to private ownership and a concomitant

rise in land and housing prices;

the growing presence of international

corporate investors and property develo-

pers integrating the city into global

capitalism;

the diverse and relatively ambitious

urban regeneration policies of the inner-

city districts, with some EU and national

government support;

the growing size of the new middle

classes with inner-city-orientated resi-

dential preferences and lifestyles, as an

outcome of post-communist social

restructuring and class formation;

the readiness of long-term residents to

invest in the renovation of their dwell-

ings acquired during the privatisation

process, as a kind of incumbent

upgrading.

Considering the social aspects of renewal,

we can conclude that urban regeneration

and upgrading in the formerly run-down

neighbourhoods of Budapest are taking

place in a smooth manner. Massive displace-

ment, evictions or social tensions among

residents could not be demonstrated (Lees,

2008). This is mainly due to the large size of

the owner-occupied sector and the social

responsibility of local governments. External

private investors have had only a limited

access to the housing stock in our research

area. If we understand gentrification as a

process of upgrading, where up-market

housing with high-status residents becomes

dominant in a formerly lower-class neigh-

bourhood, it is typical in downtown

Budapest only in those areas where new

housing construction took place due to

demolition or the regeneration of brown-

field sites. The old housing stock was less

affected by the process of gentrification.

Therefore, gentrification in the traditional

sense can be pointed out in the inner city of

Budapest geographically only in smaller

areas (such as the SEMIX and Rev8 areas).

More typical is the development of inner-

city quarters towards a more heterogeneous

pattern both in terms of the quality of the

housing stock and the social status of resi-

dents. There are not only elite gentrifiers and

alternative pioneers who contribute to the

upgrading process, but also ordinary house-

holds who prefer inner-city residential loca-

tions and follow an inner-city-orientated

lifestyle. The renovation of the building

stock is carried out not only by newcomers,

but also by those who have been living in the

area for a long time. All these can be related

to the specific pathways of post-socialist

cities retaining socially relatively mixed

inner-city communities.

There is a clear similarity between the

development of inner-city quarters in

Budapest and the upgrading processes of

East German cities where the drastic

URBAN RENEWAL IN BUDAPEST 35

by guest on October 30, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

displacement of sitting residents could not

evolve; therefore it was labelled as soft

gentrification (Wiest and Zischner, 2006).

However, the gentrification process taking

place in Budapest is soft not because of

the high vacancy rate in the rental market

and extensive public investments, like in

East Germany, but mainly due to the

extreme weight of owner-occupation and

certain control of the districts local gov-

ernment. Our examples also demonstrate

that the regeneration of neighbourhoods is

dependent very much on local conditions.

The regeneration of downtown Budapest

will undoubtedly continue in the future and

the islands of gentrification will most proba-

bly expand further, pushing the gentrifica-

tion frontier outward. However, despite the

growing pressure of gentrification, it can be

assumed that under the given circumstances

the building stock will remain heteroge-

neous in inner Budapest and a healthy social

mix will persist in the years ahead; thus, no

aggressive gentrification can be expected.

We also envisage that the regeneration of

inner-city neighbourhoods in Budapest will

result in a pattern that we may call localised

gentrification, which means that, due to the

intervention of local governments, the pro-

cess will be kept under public control. The

geographical results of all this remain to be

seen.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by a grant from the

Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG).

References

Andrusz, G., Harloe, M. and Szelenyi, I. (Eds)

(1996) Cities after Socialism: Urban and

Regional Change and Conflict in Post-socialist

Societies. Oxford: Blackwell.

Atkinson, R. and Bridge, G. (Eds) (2005) Gentri-

fication in a Global Context: The New Urban

Colonialism. London: Routledge.

Badyina, A. and Golubchikov, O. (2005) Gentri-

fication in central Moscow: a market process

or a deliberate policy? Money, power and

people in housing regeneration in Ostoz-

henka, Geografiska Annaler B, 87(2), pp.

113129.

Beauregard, R. A. (1986) The chaos and com-

plexity of gentrification, in: N. Smith and P.

Williams (Eds) Gentrification of the City, pp.

3555. Boston, MA: Allen & Unwin.

Beluszky, P. and Tima r, J. (1992) The changing

political system and urban restructuring in

Hungary, Tijdschrift voor Economische en

Sociale Geografie, 83(5), pp. 380390.

Berenyi, B. E. and Szabo , B. (2009) Housing pre-

ferences and the image of inner city neighbor-

hoods in Budapest, Hungarian Geographical

Bulletin, 58(39) pp. 201214.

Bernt, M. and Holm, A. (2005) Exploring the

substance and style of gentrification: Berlins

Prenzlberg, in: R. Atkinson and G. Bridge

(Eds) Gentrification in a Global Context: The

New Urban Colonialism, pp. 106120.

London: Routledge.

Boren, T. and Gentile, M. (2007) Metropolitan

processes in post-communist states: an intro-

duction, Geografiska Annaler B, 89(2), pp.

95110.

Boros, L., Hegedus, G. and Pa l, V. (2010) Con-

flicts and dilemmas related to the neoliberal

urban policy in some Hungarian cities, Studia

Universitatis, Babes-Bolyai, Politica, 1, pp.

3552.

Brade, I., Herfert, G. and Wiest, K. (2009) Recent

trends and future prospects of socio-spatial

differentiation in urban regions of central and

eastern Europe: a lull before the storm?, Cities,

26(5), pp. 233244.

Chelcea, L. (2006) Marginal groups in central

places: gentrification, property rights and

post-socialist primitive accumulation

(Bucharest, Romania), in: G. Enyedi and Z.

Kova cs (Eds) Social Changes and Social Sus-

tainability in Historical Urban Centres: The

Case of Central Europe, pp. 127146. Pecs:

Centre for Regional Studies of the Hungarian

Academy of Sciences.

Clark, E. (1991) Rent gaps and value gaps: com-

plementary or contradictory, in: J. van

Weesep and S. Musterd (Eds) Urban Housing

for the Better-off: Gentrification in Europe, pp.

1730. Utrecht: Stedelijke Netwerken.

36 ZOLTA

N KOVA

CS ET AL.

by guest on October 30, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Cook, A. (2010) The expatriate real estate com-

plex: creative destruction and the production

of luxury in post-socialist Prague, Interna-

tional Journal of Urban and Regional Research,

34(3), pp. 611628.

Davidson, M. and Lees, L. (2010) New-build gen-

trification: its histories, trajectories, and criti-

cal geographies, Population, Space and Place,

16(5), pp. 395411.

Egedy, T. (2010) Current strategies and socio-

economic implications of urban regeneration

in Hungary, Open House International, 35(4),

pp. 2938.

Enyedi, G. (1998) Transformation in central

European post-socialist cities, in: G. Enyedi

(Ed.) Social Change and Urban Restructuring

in Central Europe, pp. 934. Budapest: Aka-

demiai Kiado .

Foldi, Z. (2006) Neighbourhood dynamics in

inner-Budapest: a realist approach. Nether-

lands Geographical Studies No. 350, Faculty

of Geosciences, University of Utrecht.

Foldi, Z. and Weesep, J. van (2007) Impacts of

globalisation at the neighbourhood level in

Budapest, Journal of Housing and the Built

Environment, 22(1), pp. 3350.

Friedrichs, J. (1996) Gentrification: forschungs-

stand und methodologische probleme, in: J.

Friedrichs and R. Kecskes (Eds) Gentrification:

Theorie und Forschungsergebnisse, pp. 1340.

Opladen: Leskey & Budrich.

Glass, R. (1964) London: aspects of change. Report

No. 3, Centre for Urban Studies, University

College, London.

Glatter, J. (2007) Gentrification in Ostdeutsch-

land: untersucht am Beispiel der Dresdner

A

ueren Neustadt. Dresdner Geographische

Beitrage No. 11, Dresden.

Gritsai, O. (1997) Business services and restruc-

turing of urban space in Moscow, GeoJournal,

42(4), pp. 365376.

Haase, A., Grossmann, K. and Steinfuhrer, A.

(2012) Transitory urbanites: new actors of

residential change in Polish and Czech inner

cities, Cities. DOI:10.1016/j.cities.2011.11.006.

Hammel, D. J. (2009) Gentrification, in: R.

Kitchin and N. Thrift (Eds) International

Encyclopedia of Human Geography, Vol. 4,

pp. 360367. Oxford: Elsevier.

Hegedus, J. and Tosics, I. (1994) Privatisation

and rehabilitation in the Budapest inner dis-

tricts, Housing Studies, 9(1), pp. 3954.

Janko , F. (2012) Urban renewal of historic towns

in Hungary: results and prospects for future

in European context, in: T. Csapo and A.

Balogh (Eds) Development of the Settlement

Network in the Central European Countries:

Past, Present and Future, pp. 161175. Heidel-

berg: Springer.

Kabisch, N., Haase, D. and Haase, A. (2010)

Evolving reurbanisation? Spatio-temporal

dynamics as exemplified by the East German

city of Leipzig, Urban Studies, 47(5), pp.

967990.

Kempen, R. van and Bolt, G. (2009) Social cohe-

sion, social mix, and urban policies in the

Netherlands, Journal of Housing and the Built

Environment, 24(4), pp. 457475.

Kova cs, Z. (1994) A city at the crossroads: social

and economic transformation in Budapest,

Urban Studies, 31(7), pp. 10811096.

Kova cs, Z. (1998) Ghettoization or gentrifica-

tion? Post-socialist scenarios for Budapest,

Netherlands Journal of Housing and the Built

Environment, 13(1), pp. 6381.

Kova cs, Z. (2009) Social and economic transfor-

mation of historical neighbourhoods in Buda-

pest, Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale

Geografie, 100(4), pp. 399416.

Kova cs, Z. and Wiessner, R. (1999) Stadt- und

Wohnungsmarktentwicklung in Budapest. Zur

Entwicklung der innerstadtischen Wohnquar-

tiere im Transformationsprozess. Beitrage zur

Regionalen Geographie No. 48, Institut fur

Landerkunde, Leipzig.

Lada nyi, J. (2002) Residential segregation among

social and ethnic groups in Budapest during

the post-communist transition, in: P. Mar-

cuse and R. van Kempen (Eds) Of States and

Cities: The Partitioning of Urban Space, pp.

170182. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lees, L. (2008) Gentrification and social mixing:

towards an inclusive urban renaissance?,

Urban Studies, 45(12), pp. 24492470.

Lees, L., Slater, T. and Wyly, E. (2008) Gentrifica-

tion. New York: Routledge.

Leetmaa, K. and Tammaru, T. (2007) Suburbani-

zation in countries in transition: destination

of suburbanizers in the Tallinn metropolitan

area, Geografiska Annaler B, 89(2), pp.

127146.

Ley, D. (1981) Inner-city revitalization in

Canada: a Vancouver case study, Canadian

Geographer, 25(2), pp. 124148.

URBAN RENEWAL IN BUDAPEST 37

by guest on October 30, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Marcinczak, S. and Sagan, I. (2011) The socio-

spatial restructuring of Lo dz, Poland, Urban

Studies, 48(9), pp. 17891809.

Musterd, S. and Andersson, R. (2005) Housing

mix, social, mix and social opportunities,

Urban Affairs Review, 40(6), pp. 761790.

Nagy, E. and Tima r, J. (2012) Urban restructur-

ing in the grip of capital and politics: gentrifi-

cation in east central Europe, in: T. Csapo and

A. Balogh (Eds) Development of the Settlement

Network in the Central European Countries:

Past, Present and Future, pp. 121135. Heidel-

berg: Springer.

Ourednicek, M. (2007) Differential suburban

development in the Prague urban region, Geo-

grafiska Annaler B, 89(2), pp. 111126.

Phillips, M. (1993) Rural gentrification and the

process of class colonisation, Journal of Rural

Studies, 9, pp. 123140.

Rerat, P. and Lees, L. (2011) Spatial capital, gen-

trification and mobility: evidence from Swiss

core cities, Transactions of the Institute of Brit-

ish Geographers, 36(1), pp. 126142.

Rerat, P., Soderstrom, O. and Piguet, E. (2010)

New forms of gentrification: issues and

debates, Population, Space and Place, 16(5),

pp. 335343.

Ruoppila, S. and Kahrik, A. (2003) Socio-

economic residential differentiation in post-

socialist Tallinn, Journal of Housing and the

Built Environment, 18(1), pp. 4973.

Smith, N. (1979) Toward a theory of gentrifica-

tion: a back to the city movement by capital,

not people, Journal of the American Planning

Association, 45(4), pp. 538548.

Smith, N. (1996) The New Urban Frontier: Gen-

trification and the Revanchist City. London:

Routledge.

Standl, H. and Krupickaite, D. (2004) Gentrifi-

cation in Vilnius (Lithuania): the example of

Uzupis, Europa Regional, 12(1), pp. 4251.

Sy kora, L. (1999) Processes of socio-spatial dif-

ferentiation in post-communist Prague,

Housing Studies, 14(5), pp. 677699.

Sy kora, L. (2005) Gentrification in post-

communist cities, in: R. Atkinson and G.

Bridge (Eds) Gentrification in a Global Con-

text: The New Urban Colonialism, pp. 90

105. London: Routledge.

Sy kora, L. (2009) Post-socialist cities, in: R.

Kitchin and N. Thrift (Eds) International

Encyclopedia of Human Geography, Vol. 8,

pp. 387395. Oxford: Elsevier.

Temelova , J. (2007) Flagship developments and

physical upgrading of the post-socialist inner-

city: the Golden Angel project in Prague, Geo-

grafiska Annaler B, 89(2), pp. 169181.

Wec1awowicz, G. (2002) From egalitarian cities

in theory to non-egalitarian cities in practice:

the changing social and spatial patterns in

Polish cities, in: P. Marcuse and R. van

Kempen (Eds) Of States and Cities: The Parti-

tioning of Urban Space, pp. 183199. Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

Weiske, C. (1996) Gentrification and incumbent

upgrading in Erfurt, in: J. Friedrichs and R.

Kecskes (Eds) Gentrification: Theorie und

Forschungsergebnisse, pp. 193226. Opladen:

Leske & Budrich.

Wiest, K. and Zischner, R. (2006) Aufwertung

innerstadtischer Altbaugebiete in den neuen

Bundeslandern: Prozesse und Entwicklungsp-

fade in Leipzig, Deutsche Zeitschrift fur Kom-

munalwissenschaften, 45(1), pp. 99121.

38 ZOLTA

N KOVA

CS ET AL.

by guest on October 30, 2014 usj.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Вам также может понравиться

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5795)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1091)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Medcs Problems and Solutions Ib SLДокумент9 страницMedcs Problems and Solutions Ib SLapi-253104811Оценок пока нет

- Le Corbusier Forays Into Urbanism: CT - LAKSHMANAN B.Arch.,M.C.P. SRM School of ArchitectureДокумент22 страницыLe Corbusier Forays Into Urbanism: CT - LAKSHMANAN B.Arch.,M.C.P. SRM School of ArchitectureRohanABОценок пока нет

- Article For Gentrification Reseach Paper (Essay 4)Документ4 страницыArticle For Gentrification Reseach Paper (Essay 4)msdrawbondОценок пока нет

- WWW Learnit3dДокумент2 страницыWWW Learnit3dDanielОценок пока нет

- Zoning of NairobiДокумент10 страницZoning of NairobiTitus K. Biwott100% (1)

- Elements of Urban DesignДокумент14 страницElements of Urban DesignMd Rashid Waseem0% (1)

- Glavni Gradovi PDFДокумент1 страницаGlavni Gradovi PDFjacCulyОценок пока нет

- 3.3 The Changing Structure of Urban SettlementsДокумент17 страниц3.3 The Changing Structure of Urban SettlementsLinda Strydom100% (1)

- Types of HousesДокумент12 страницTypes of HousesClaris CaintoОценок пока нет

- Contemporary Nigerian Residential ArchitectureДокумент46 страницContemporary Nigerian Residential ArchitectureSamuel Hugos100% (1)

- The Importance of Dealth and Life FinalДокумент25 страницThe Importance of Dealth and Life Finaloanama232Оценок пока нет

- Property List - Emaar PortДокумент54 страницыProperty List - Emaar PortAnonymous 2rYmgRОценок пока нет

- DharaviДокумент2 страницыDharaviGeoBlogsОценок пока нет

- Definitions of Town PlanningДокумент5 страницDefinitions of Town PlanningShane RodriguezОценок пока нет

- Growth Pattern in UdaipurДокумент7 страницGrowth Pattern in UdaipurDeepesh KothariОценок пока нет

- Shorooq MirdifДокумент11 страницShorooq MirdifmetsfujОценок пока нет

- Housing TypesДокумент12 страницHousing TypesSheree Nichole GuillerganОценок пока нет

- Mudon Views Apartments by Dubai Properties +97145538725Документ27 страницMudon Views Apartments by Dubai Properties +97145538725SandeepОценок пока нет

- Urban Growth and Decline - EssayДокумент2 страницыUrban Growth and Decline - EssayShubham ShahОценок пока нет

- 12.winnipeg Centre Village Final Documentation BoardДокумент2 страницы12.winnipeg Centre Village Final Documentation Boardpravesh_bansal87Оценок пока нет

- Municipality of Murrysville Comprehensive Plan 2002Документ160 страницMunicipality of Murrysville Comprehensive Plan 2002Fred WilderОценок пока нет

- Residential Projects Update To Forney City Council On Aug. 15Документ30 страницResidential Projects Update To Forney City Council On Aug. 15inForney.comОценок пока нет

- CPM Listing-20160106Документ9 страницCPM Listing-20160106SenyumSajerОценок пока нет

- Residential Building's Setbacks, Facades, Entries - Urban DesignДокумент15 страницResidential Building's Setbacks, Facades, Entries - Urban DesignAhmad ReshadОценок пока нет

- Case StudyДокумент159 страницCase StudyChania BhatiaОценок пока нет

- 83 Elmsdale DR, Kitchener - Official Plan Amendment & Zone Change ProposalДокумент71 страница83 Elmsdale DR, Kitchener - Official Plan Amendment & Zone Change ProposalWR_Record100% (1)

- Typology GISДокумент1 страницаTypology GISSpectrum News TexasОценок пока нет

- HKDSE Geography M4Документ7 страницHKDSE Geography M4Jonathan NgОценок пока нет

- Act 172 Development Control SystemДокумент14 страницAct 172 Development Control SystemDm Wivinny JesonОценок пока нет

- MallsДокумент3 страницыMallsMandeep SinghОценок пока нет