Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

How Florida State Used Science On Football Player Workouts

Загружено:

FballGuru0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

148 просмотров5 страницTalking about Catapult heart monitors for football.

Оригинальное название

How Florida State Used Science on Football Player Workouts

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

DOCX, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документTalking about Catapult heart monitors for football.

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате DOCX, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

148 просмотров5 страницHow Florida State Used Science On Football Player Workouts

Загружено:

FballGuruTalking about Catapult heart monitors for football.

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате DOCX, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 5

How Florida State Used Science on

Football Player Workouts

Posted by cmorris on Sep 1, 2014 in Muscle and Fitness, Training | 0 comments

BY NOAH DAVIS Mens Fitness

Rashad Greene, a 6-foot, 180-pound speedster from Albany, GA, may very well end his collegiate career as

the greatest wide receiver in the history of Florida State University football. No humble feat, of course. FSU is a

perennial powerhouse and gridiron talent factory that in recent years has churned out top NFL receivers like

Kelvin Benjamina first-round draft pick this yearas well as big names like Peter Warrick, Laveranues

Coles, and three-time Pro Bowler Anquan Boldin.

In 2013, Greene caught 76 balls, the second-highest total ever in a single Seminoles season, and snagged

nine receptions for 147 yards in the 2014 national championship game against Auburn. The Seminoles won.

This season, Greene is primed to break FSUs all-time records for total receiving yards, career receptions, and

receiving touchdownsthe first two are records that have stood since 1968.

But, for all his accolades, promise, and well-earned swagger around FSUs practice field, today the 21-year-old

nursing major with the quiet temperament is just another player whos slacking his way through a workout.

And theres no way he can hide it.

Greene, along with the rest of the Seminoles skill guysspeedy wide receivers and defensive backsis

going through a series of grueling conditioning sprints on the turf at FSUs new $15 million indoor facility, near

the end of the teams spring practices in Tallahassee. Vic Viloria, a stout former linebacker whos now the

teams head strength and conditioning coach, oversees the drill. Instead of focusing solely on the players,

however, his staffers are glued to an array of computer monitors that display a constantly updating stream of

colorful numbers, bar graphs, and pie charts. Some of the numbers indicate that Greene might be dogging it a

little.

The information comes from a sensor about half the size of an iPhone 4, which Greenealong with every

other playerwears on his back under the uniform, held in place by a triangle-shape sports bow secured at

the neck and under the armpits.

Developed by an Australian sports science company, Catapult, the sensor tracks more than 100 metrics,

including distance, speed, acceleration, deceleration, and heart rate. It also monitors change in direction using

3-D accelerometers, 3-D magnetometers (essentially digital compasses), 3-D gyroscopes, a GNSS antenna for

GPS, and a processor with a memory unit. As it collects data, the sensor transmits numbers wirelessly to the

coaches sideline command center. There the computers use algorithms that factor in the players vitals and

other biographical info, then elegantly format the information into readableand actionablegraphs and

charts.

At Florida State, the data is sacred. This is a football program that finished in the top 5 of the Associated Press

poll every year from 1987 to 2000, routinely steamrolling its opposition in the Atlantic Coast Conference. But it

struggled through a slump in the 2000s, in the twilight of the tenure of long-running head coach Bobby

Bowden. Recently, though, the team has surged back to prominence under new head coach Jimbo Fisher, a

longtime Bowden acolyte who took over the top job in 2010. The data never lies, argues Fisher, who credits it

for helping guide the Seminoles back to their rightful place atop the world of college football. Its helping me

manage the team in terms of where we want to peak during the year, he says, speaking at the pace of a

hyperactive child.

On the practice field, Viloria notices that Greene is slowing up a few yards before the end of each sprint. In the

past, Viloria wouldve had only his eyes and intuition for such a split-second observation, but now the sensors

offer figures to back it up.

Greene, like the rest of his teammates, knows not to question the data; so when Viloria shakes his head and

tells him the last sprint didnt counthe slacked off in the final stretchGreene doesnt argue or hang his head

in complaint. He merely lines up and does another 100-yard gasser, running full-bore to the very end.

He looks over at Viloria, whose readout confirms the effort. Greene hits the showers as the coach smiles,

another training session altered slightly but significantly, another national championship a fraction closer.

Welcome to the new age of football, where real-time information influences a head coachs practice decisions

on a daily basis, and every athlete gets an individualized training program intended to maximize potential and

reduce injury. And the Seminoles, headed by the irrepressible Fisher, are leading the way.

FSU football was the first major college football program to really adopt the Catapult technology, says Ethan

Owens, a sports scientist for the company. We created it, but they had to figure out how to take it and use it to

benefit FSU football.

The Seminoles became Catapults first U.S. client in 2011, a year after Fisher took over the team. Viloria and

his then assistants, Erik Korem and Joe Danos, pitched him on the Catapult devices after seeing them in

action at a practice of an Australian rules football team, the Greater Western Sydney Giants.

Catapult was founded in 2001 by engineers Shaun Holthouse (now the companys CEO) and Igor van de

Griendt. The duo developed a unique athlete-tracking microtechnology, and eventually found themselves

working with several Aussie pro football teams.

Viloria and Korem, fascinated by what they learned from watching the Catapult system in action, brought the

idea back to their head coach. Fisher, always searching for an edge in the hypercompetitive world of elite

college football, approved the program.

The first year, FSU used 30 GPS sensors for the entire team. Initially, Viloria says, the data was little more

than noise, what with the small sample size and the fact that the Australian sports scientists who designed

Catapult didnt know what stats to cull for an American football team. Each sport, they argue, comes with sport-

specific movements and conditioning drills that produce wear and tear on the body in different ways. But as

FSU gathered more dataadding additional sensors each year, topping out at 80 this season (at the cost of

more than $100,000 a year)they began to develop profiles for different types of players. Previously, Viloria

could only theorize that a series of sprints or route-running drills would have a different effect on Greene (6,

178 pounds) than on Benjamin (65, 234 pounds). If I take two guys with different body types out on the field,

well, ****the same workload is going to be a lot more stress on one than on the other, Viloria says. We

knew it before, we just couldnt prove it.

So last year, the much heavier Benjamin ran shorter conditioning sprints (90 yards) than the lithe Greene (a full

100 yards). Big offensive linemen, meanwhile, went 60 yards. Each individual player can only sprint for so

long, Viloria says. Beyond that, its no longer speed. Its not cardio or endurance either, because theyre

exceeding the heart-rate zone you want them to be in. At the end of the day, if you get rid of that, you get rid of

a lot of potential injury.

Viloria now establishes benchmarks at the beginning of the season for each playersimilar to a weight room

max-out figurethat can be followed all year. Its been a total culture change, he says. Everyone used to run

the same distance. But in the weight room, we wouldnt ask a 190-pound guy to lift what a 300-pound guy lifts.

That would just be stupid. The only reason we know that is because we get baseline numbers. We do the

same with the sensors on the field.

The data also provides a way to cut through the obstacles of player personality and stubbornness. For

example, if Greene can sprint at 20 miles per hour for 100 yards without slowing down, the coaching staff can

tell him to run at 80% for a training session and observe if hes following through or not. It takes all the

guesswork out of it, Fisher says. Some guys dont show how tired they are. Others do. This lets me have

correct data so I can make direct decisions. We know over a period of time where each guy performs his best

at the end of the week, so we can adjust each practice specifically for him. Players arent cattle. You cant train

them all the same. They all have different parts.

The Catapult sensors arent your average Garmins or Jawbones, either, delivering only basic information like

heart rate and speed. The system relies on proprietary algorithms that vacuum up several metrics in real time

and assemble them in easily digestible ways. The most important metric for FSU, for instance, is the all-

encompassing PlayerLoad variable, which takes into account sagittal, frontal, and transverse planes of

motionbasically, movement in every directionas well as other factors like age, weight, high-intensity

running, time spent walking versus running versus sprinting, and the number of accelerations and

decelerations.

PlayerLoad crunches the numbers to provide a single figure that represents how hard a players working.

Call it the Holy Grail number, the figure that turns all this fancy verbiage into football talk, says Viloria.

Based on those PlayerLoad numbers, Fisher, Viloria, and the rest of the staff may keep a practice going, end it

a couple minutes early if the entire group is overworked, or instruct individual players to take a rest if their

workload gets too far over their benchmark.

When practice ends, Fisher studies a printout detailing the workload of every single FSU player who was

micd upteam lingo for wearing a sensor. If the team was supposed to go 80% but went 85%, hell dial back

the next day to give his troops some rest by increasing repetitions but lowering the intensity, or reducing the

amount of physical contact between players. This, he says, keeps players in football condition while

simultaneously giving their bodies and muscles a bit of a rest so they can peak in time for the games. For all

the data programs success, Fisher was initially skeptical about the role of data in monitoring and maximizing

cardiovascular fitness.

It really was hard for me to adapt, because its against everything Ive ever been taught in sports, he says. In

football, he points out, players are supposed to go 100% all the time. Anything else runs counter to the sports

religionthat melodramatic, Rudy-esque belief that players should always be pushing themselves, painfully,

to some metaphysical limit in hopes of improvement. But, according to Fisher and Catapult scientists, that

mindset is not only rapidly becoming obsolete, but has possibly been dangerous all along.

You wouldnt drive a car in a race without a dashboard, so why do we do that with our athletes? says Gary

McCoy, Catapults senior applied sports scientist in the U.S. He argues that we all have different-size engines

that can operate at full speed for only so longand no two are the same.

Fishers opinions on the benefits of data changed as he saw its effects. In 2013, when the teams data-

monitoring program was in full swing, the Seminoles began the season ranked 12th in the USA Today poll

and never stopped winning. They won nine straight games by at least 27 points, including four against ranked

opponents. FSU finished a perfect 140, defeating Auburn 3431 in the national championship game on a

dominating drive during which they looked as fresh as they had in the first quarter.

We were able to peak damn near every week because we had all the data coming back, Viloria says.

The team also dramatically reduced injuries. Soft-tissue injuriesmuscle, ligament, and tendon issues that

arise from overstretching, lack of strength, and, most important, fatigueare down 88% over the past two

seasons, primarily because FSU is limiting overtraining.

Most soft-tissue injuries are preventable, says sports scientist Michael Regan. Were giving them a tool to

measure the movement of their athletes, and, therefore, their fatigue and load. By building up benchmark data,

youre understanding the risk of soft-tissue injuries and can be proactive in reducing them. Not a single player

missed a game in 2013 due to one. Thats a remarkable statistic for such a high-level NCAA football program.

(The University of Florida, meanwhile, suffered 10 season-ending injuries during the same stretch.)

Conditioning drills are safer as well. Weve been able to stop five or six heatstroke situations by monitoring

players heart rates during practice, Fisher says. Wed go grab a guy, get him cooled down, then get him back

out there. Viloria, the man overseeing the cardio training, put it even more simply. I dont have to wait until the

guy passes out to sit him down, he says.

Its an about-face for Viloria. The first year, when the data didnt really make sense, I was the typical

bonehead. I began to think that I didnt need the ****ing computer to tell me how to do my job. The second

year, I thought it was OK. Now, I really feel bad for the teams that dont have it. Its gonna extend careersand

save kids lives.

Catapult has also been a boon for recruiting. Fisher uses the data-monitoring program not only as a selling

point for the university, but also as a means of better preparing players for a pro career. He argues that the

data will help deliver them to the sports highest level in the best possible shape.

In 2011, Kelvin Benjamin arrived at FSU as the eighth-best high school wide receiver in the country, according

to *****s.com. And though he caught 30 passes in 2012, the coaching staff felt he was relying on his physical

gifts during games, content to glide through training sessions. Given his massive size and quickness, he

should have dominated. Viloria believes that providing real-time feedback to Benjamin helped convince him

that he needed to work harder on the practice field.

Theres no more arguing, says Viloria. I dont have to be the typical strength coach. I give them a number

and show them where they should be. It gives them some ownership. Its their body.

Other teams are catching on. Oregon and LSU use Catapults trackers for their programs, though they have

nowhere near FSUs 80 sensors. The University of Kentuckys football team hired away former Viloria assistant

Erik Korem to run its GPS program, while Viloria disciples Joe Danos and Alex Hampton now work as strength

and conditioning coaches with the NFLs New York Giants and Jacksonville Jaguars, respectively. In total,

Catapult has contracts with 19 college programs and 14 NFL teams.

Catapult doesnt offer a consumer product yet. Thats coming in the future, according to CEO Shaun

Holthouse. He believes that it will lead a new wave of wearable, high-performance devices that not only

measure your outputs but also run them through algorithms and help do your thinking for you. For example, if

youre a long-distance runner, youll have your own version of the PlayerLoad variable, which will incorporate

your heart rate, weight, and age, and be able to tell you if youre slacking or going too hard. The same will

apply to all kinds of endurance activities.

You could compare it to Formula 1, where great high-end technology is developed and proven at the elite

level, then over time makes it down to production cars, Holthouse says. The great thing about our technology

is its strong scientific pedigree and the fact that it has such a demonstrable performance benefit for the worlds

most elite athletes. Its very different from bottom-up devices like Fitbit and the Nike+ FuelBand, which are

focused more on sedentary lifestyles and obesity problems.

Fisher agrees. Winning isnt about going 100% all the time, he says; its about peaking at the right time.

The last two years are when weve really been able to use it, he says, and were 26 and 2. Injuries are down.

Weve had two ACC championships and a national championship.

And, hell tell, FSU is just getting started.

See more at: http://www.mensfitness.com/life/spor.SAud8tOG.dpuf

Вам также может понравиться

- History of Pro Football PlaylistДокумент1 страницаHistory of Pro Football PlaylistFballGuruОценок пока нет

- Super Sunday PlaylistДокумент1 страницаSuper Sunday PlaylistFballGuruОценок пока нет

- Complete Offensive LineДокумент201 страницаComplete Offensive Linedline99100% (9)

- Catapult ArticlesДокумент15 страницCatapult ArticlesFballGuruОценок пока нет

- Defensive Football BasicsДокумент20 страницDefensive Football BasicsFballGuru100% (1)

- Cornell Special Teams: "Dominate Your Assignment"Документ22 страницыCornell Special Teams: "Dominate Your Assignment"delgadog125607Оценок пока нет

- Butch Jones 2015 ClinicДокумент1 страницаButch Jones 2015 ClinicFballGuruОценок пока нет

- New NCAA Academic Standards 2016Документ5 страницNew NCAA Academic Standards 2016FballGuru100% (1)

- John Robinson - The USC Running GameДокумент8 страницJohn Robinson - The USC Running GameFballGuru100% (1)

- Lane Kiffin Playbook - USC Trojans 2010Документ53 страницыLane Kiffin Playbook - USC Trojans 2010jeaves1492% (13)

- 2014 Ohio State Clinic NotesДокумент22 страницы2014 Ohio State Clinic NotesFballGuru100% (7)

- 2007 UCLA Special TeamsДокумент100 страниц2007 UCLA Special TeamsFballGuru100% (7)

- Dennis Erickson - One Back OffenseДокумент12 страницDennis Erickson - One Back OffenseFballGuru0% (1)

- FSU Rides Catapult GPS Technology To TitleДокумент4 страницыFSU Rides Catapult GPS Technology To TitleFballGuruОценок пока нет

- UCLA Offensive Game Plan Vs BYU 2007Документ91 страницаUCLA Offensive Game Plan Vs BYU 2007FballGuru100% (5)

- Bill Walsh - A Method For Game-PlanningДокумент10 страницBill Walsh - A Method For Game-PlanningFballGuru100% (7)

- 2009 Character Themes - Lambuth UДокумент19 страниц2009 Character Themes - Lambuth UFballGuru100% (1)

- 2010 U. of Tulsa Offensive PhilosophyДокумент2 страницы2010 U. of Tulsa Offensive PhilosophyFballGuruОценок пока нет

- Al Davis StoriesДокумент17 страницAl Davis StoriesFballGuru100% (1)

- Lou Holtz - The PlanДокумент12 страницLou Holtz - The PlanFballGuru100% (2)

- UW-Platteville Installing The Spread With No-Huddle Capability Part-2Документ13 страницUW-Platteville Installing The Spread With No-Huddle Capability Part-2FballGuruОценок пока нет

- Counting System For O-LineДокумент6 страницCounting System For O-LineFballGuru100% (2)

- Clinic Notes Costa MesaДокумент8 страницClinic Notes Costa MesaFballGuruОценок пока нет

- Alex Gibbs On The Outside ZoneДокумент12 страницAlex Gibbs On The Outside ZoneGBO98Оценок пока нет

- Ithaca Unbalanced Spread Offense - Terry H...Документ13 страницIthaca Unbalanced Spread Offense - Terry H...FballGuru83% (6)

- 2013 MN Football Coaches Association ClinicДокумент10 страниц2013 MN Football Coaches Association ClinicFballGuru0% (1)

- UW-Platteville Installing The Spread With No-Huddle Capability Part-3Документ9 страницUW-Platteville Installing The Spread With No-Huddle Capability Part-3FballGuruОценок пока нет

- UW-Platteville Installing The Spread With No-Huddle Capability Part-4Документ11 страницUW-Platteville Installing The Spread With No-Huddle Capability Part-4FballGuruОценок пока нет

- 2010 U. of Tulsa Spring OffenseДокумент98 страниц2010 U. of Tulsa Spring OffenseFballGuru0% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Makiwara Training Carl CestariДокумент7 страницMakiwara Training Carl Cestaritharaka1226Оценок пока нет

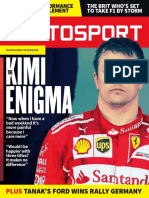

- The Kimi Enigma - Autosport 24th August 2017Документ16 страницThe Kimi Enigma - Autosport 24th August 2017Anonymous AyGXao100% (2)

- Andreatta Article James LeBeauДокумент8 страницAndreatta Article James LeBeauxjaxОценок пока нет

- Fightopia RulesДокумент1 страницаFightopia RulesAaron TudykОценок пока нет

- Magura HS 11/33Документ16 страницMagura HS 11/33Nebojša TepićОценок пока нет

- Teen Habits Online and OfflineДокумент1 страницаTeen Habits Online and OfflinebohucОценок пока нет

- Umpiring Techniques Hand SignalsДокумент2 страницыUmpiring Techniques Hand Signalsapi-431813813Оценок пока нет

- 2018 Fnia Notes Week 6Документ7 страниц2018 Fnia Notes Week 6api-445010354Оценок пока нет

- Ba FrostjokeДокумент3 страницыBa FrostjokeCakradenta Yudha PoeteraОценок пока нет

- Winter Workouts - Complete Track and FieldДокумент8 страницWinter Workouts - Complete Track and FieldCALF67% (3)

- Promotion Exams: Requirements For Rank Novice To Black SashДокумент21 страницаPromotion Exams: Requirements For Rank Novice To Black SashSamuel LamОценок пока нет

- Dinosaur Arm TrainingДокумент34 страницыDinosaur Arm TrainingMarkk211100% (4)

- The Ultimate Push Pull Legs System - 4xДокумент180 страницThe Ultimate Push Pull Legs System - 4xGilel Drucker50% (2)

- Metro Cash Carry IndiaДокумент23 страницыMetro Cash Carry IndiaRocky GreenОценок пока нет

- Olthof Et Al. - 2019 - A Match-Derived Relative Pitch Area Facilitates THДокумент8 страницOlthof Et Al. - 2019 - A Match-Derived Relative Pitch Area Facilitates THAlvaro Muela SantosОценок пока нет

- NO Nama Nopol Type No - TLP Srvs Sblmnya: Daftar Reminder Bulan April 2013Документ10 страницNO Nama Nopol Type No - TLP Srvs Sblmnya: Daftar Reminder Bulan April 2013Anton YuliОценок пока нет

- Document19 2nd14rdДокумент2 069 страницDocument19 2nd14rdPcnhs SalОценок пока нет

- Woman workout-plan-PPLS-extra-GlutesДокумент9 страницWoman workout-plan-PPLS-extra-Glutesbomcon123456Оценок пока нет

- Attire Equipm WPS Office FinalДокумент24 страницыAttire Equipm WPS Office FinalJames RamosОценок пока нет

- If You Are Not Nuno Alves Please Destroy This Copy and Contact WORLD CLASS COACHINGДокумент52 страницыIf You Are Not Nuno Alves Please Destroy This Copy and Contact WORLD CLASS COACHINGNuno Alves100% (1)

- 2015 Men'S Dets (Updated 25mar15)Документ2 страницы2015 Men'S Dets (Updated 25mar15)joshjonesОценок пока нет

- HIIT Review Gibala PDFДокумент6 страницHIIT Review Gibala PDFThiago LealОценок пока нет

- DATABASE Update Februari 2015Документ111 страницDATABASE Update Februari 2015Pakdhe RoedhyОценок пока нет

- Survival at Sea 1950Документ156 страницSurvival at Sea 1950CAP History Library100% (1)

- Volume 1Документ8 страницVolume 1jkd01Оценок пока нет

- Motion 8 This House Would Ban BoxingДокумент4 страницыMotion 8 This House Would Ban BoxingSanti Sri HartiniОценок пока нет

- Newtrasdata Ecu ListДокумент7 страницNewtrasdata Ecu ListdoktorskiОценок пока нет

- Beginner Marathon - NewДокумент6 страницBeginner Marathon - Newramcruise29232Оценок пока нет

- Misliti Design PDFДокумент182 страницыMisliti Design PDFkophОценок пока нет

- PASSAGE PLANNING. Rastannurah To Jabal AliДокумент4 страницыPASSAGE PLANNING. Rastannurah To Jabal AliKunal Singh100% (2)