Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Batanes

Загружено:

Mark Anthony FauneАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Batanes

Загружено:

Mark Anthony FauneАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The Batanes group of islands is the northernmost province of the Philippines.

It is

located between 121 45' to 122 15' east longitudes, and at 2015' north latitudes.

Batanes is closer to Taiwan than to the northern tip of Luzon. Of the 10 volcanic islands

composing the province, only three are inhabited. They are Batan (where the

provincial capital of Vasay (Basco) is located), Sabtang, and Itbayat. A fourth, Ivuhos,

lying about a kilometer and a half cast of Sabtang, has a handful of families tending

cattle. The other uninhabited islands are Yami, North, Mavudis, Siayan, Di-nem and

Dequey. The province has a total land area of 230 km, the country's smallest (Alonzo,

1965).

Batanes is classified as having Type A climate, a pleasant semi-temperate

climate. The Ivatan (people of Batanes) recognize two seasons: rayun (summer),

which lasts from March to May, amian (winter) from November to February.

Kachachimuyen are the rainy months for the rest of the year, except for a brief spell of

warm weather (dekey a rayun) in the two weeks between September and October.

The province has six towns: Ivana, Uyugan, Mahatao, Basco (all in Batan island),

and the island-municipalities of Sablang and Itbayat.

The People

One of the earliest eyewitness accounts on the Ivatan is that of the British buccaneer

William Dampier in 1687. He described the people as "short, squat people: generally

round visaged, hazel eyes, small yet bigger than Chinese (hazel eyes are light reddish

brown, usually flecked with green or gray); low foreheads; thick eyebrows; short low

noses; white teeth; black thick hair, lank that is worn short, just covering the ears, cut

round, very even; and very dark, copper-colored skin."

The 1990 census of the National Statistics Office reported a total population of

15,026, an increase of 24% over the 1980 population of 12, 091. These were

distributed on the six municipalities with 38% residing in Basco, 23% in Itbayat, 12% in

Sabtang, 11% in Mahatao, and 8% both for Uyugan and Ivana.

Origins

Where did the people of Batanes come from? Available documents, legends, and other

folk materials do not tell us much about their origin. Scholars are still debating whether

the prehistoric Ivatan came from the northern part of Luzon or from the southern part of

mainland China or Taiwan. However, their racial affinities to the Malays and the

structure of their language make it almost certain that they proceeded from some other

part of the Philippines. Genetic studies of Omoto (1996), a Japanese anthropologist, of

the Yami of Orchid Island (Lanyu) show closer genetic affinity of the Yami to the

Tagalog and Visayan and linguistically to the Basiic sub-branch of the Malayo-

Polynesian branch. The Yami traces their roots through their folklore from the Batanes

Islands.

Language

The language is also called Ivatan. It is a distinct Austronesian language different

from the northern Luzon languages. It has two dialects, namely, Ivatan spoken in the

islands of Batan and Sabtang and Itbayat spoken in the islands of Itbayat. English

and Tagalog are widely spoken and understood by the Ivatan (Hidalgo, 1996). The

Ivatan language in spite of its obvious difference from all other Filipino languages,

reveals on a closer analysis, an identity of structure in the composition of particles in its

root (Hidalgo, 1996).

Education

Batanes have a literacy rate of 95% higher than the national average of 93%.

There are 19 elementary schools in the province, 11 of which offer complete courses

from grades one to six. All of the six municipalities have secondary schools and a

comprehensive national high school is located in the capital Basco with branches in

Mahatao and Ivana. There is also a School of Fisheries in Sabtang, the Batanes

Polytechnic College in Basco, while an agricultural high school has been put up in

Itbayat. St. Dominic College is the only school that offers vocational courses,

baccalaureate courses in arts, commerce and education, and recently, graduate

courses in education.

History

The Batanes group of islands came in late into the folds of Spanish colonial power.

"Freedom had been the Ivatan experience for as long as they existed. That ended on

June 26, 1783, with the annexation of Batanes by the Spanish Colonial State in the

Philippines. Not that the Ivatans were conquered on the day but June 26 marked the

beginning of the process of eventual conquest. The Ivatans would be under Spain for

115 years and would not be free again until September 18, 1898." (Hidalgo

1996:113). Ironically, June 26 is being celebrated by the entire province as Batanes

Day (Foundation Day).

Culture and Traditions

No other cultures in the Philippines have mastered the rages of the seasonal typhoons

as the Ivatan. Their culture is a product of long history of struggle and adaptation to

typhoons, the rough seas, and meager resources. It exemplifies the harmonious

relationship of people with their environment.

The Houses

Before the coming of the Spaniards, the Ivatan lived in very small and low cogon

houses well situated to maximize the protection against strong winds. The Spaniards

introduced large-scale production of lime for the construction of the now famous

"traditional" Ivatan stone-houses, with exceptionally thick cogon roofs, that could

withstand the strongest typhoon.

Food and Production

Small islands usually have limited carrying capacities. The seas are hospitable only for

a few months (March, April, May) every year. Flying fish (dibang) and dolphinfish

(arayu) fishing are the highlights of the fishing season. The meager resources taught

the Ivatan to scrimp on every resource that they have. They do not waste food or

anything. Food security of the household is a continous concern of every household.

The scarcity of resources produced food patterns unique to this culture. They

have uvud (banana stalk pith), vunes (dried taro stalk), kudit (dried cow, carabao,

or pig skin), lunyis (pork cooked in its own fat) as insurance against unexpected

food shortages. They are also masters of recycling; few things go to the garbage dump.

They are also excellent farmers producing most of the food that they need, especially

rootcrops like yam (uvi, dukay), sweet potato (wakay), and taro (sudi). Each

household is oftentimes self-sufficient enjoying a considerable degree of independence.

Chickens, goats, and pigs are occassional protein sources. Cattle are raised mainly for

cash but also slaughtered during festivities. Garlic is the other cash crop. Most recently,

the Ivatan started to depend on rice, supplied by the National Food Authority from

Luzon, as their staple instead of the usual rootcrops.

Religion

Today, the Ivatan are basically Catholic. Their religious devoutness can be attributed

to the persistent and dedicated works of the early Dominican priests. However, there

are a growing number of other Christian denominations especially in the capital town.

Regardless of this, the Ivatan still believe in the influence of the world of the anyitus

(ghosts or soul of dead ancestors. Although they do not worship them, they conduct

rituals and offerings to appease or placate an anyitu.

Kinship

The family is still the strongest social unit among the Ivatan. Extended families are

still widely accepted among many Ivatan households. Because of the constant threat

from the elements, the Ivatan has to rely on its close family ties or kinsmen (kalipusan)

and friends for support. "The family concept developed a networking system based on

blood relations, kinship, so that marriages across subtribes and those from other

territories expanded this network. These relations, by tradition, were constantly

cultivated through visits , sharing whatever produce, catch, animals were available;

attendance and participation in family celebrations and gatherings. It was bad manners

not to pay a call to a kin, if one were in the neighborhood. Strengthening these ties was

so important." (Hidalgo 1996.97).

Other cultural markers of the Ivatan

Like most lowland Philippine communities, the Ivatan were totally Christianized by the

Dominican friars. But unlike most of these communities, the Ivatan retained quite a

number of its distinct cultures. Payuhwan and yaru are work groups that until now are

the mainstays of community and farm work. The vakul is also distinctly Ivatan. It is a

woman's headgear that covers the head and back keeping the wearer cool during

the long hours of work in the field. The Ivatan's tataya is another cultural marker.

Unlike any other boats all over southeast Asia and Oceania, the tataya is closer to the

European boat-making tradition. The uvud and vunes (mentioned earlier) are the

greatest food extenders that challenge any discriminating palate. The ritual and

festivities associated with uvu planting cannot be found anywhere else in the

Philippines. The mayvanuvanua ritual to open the fishing season of dibang (flying

fish) and arayu (dolphin fish) is only found among the Yami of Orchid Island in

Taiwan. They have the palu-palu (traditional dance),ururan (grinding

stone), chayi and natu (fruits), kalusan (work songs), laji (ancient lyrical songs)

and their passion for alcohol is proverbial. The list will be endless the longer we

learn and understand the Ivatan culture.

Вам также может понравиться

- History of BatanesДокумент5 страницHistory of BatanesELSA ARBREОценок пока нет

- LEYTEДокумент23 страницыLEYTEkessemehye tiwangОценок пока нет

- The History of Cagayan de Oro CityДокумент4 страницыThe History of Cagayan de Oro CityNiña Miles TabañagОценок пока нет

- Spanish Colonial Policies Written ReportДокумент12 страницSpanish Colonial Policies Written ReportReymart James Purio MorinОценок пока нет

- From Deen BenguetДокумент17 страницFrom Deen BenguetInnah Agito-RamosОценок пока нет

- The Obu Manuvo TribeДокумент2 страницыThe Obu Manuvo TribeDE ORO TRAVELSОценок пока нет

- I. Profile: Calaoan Ancestral DomainДокумент29 страницI. Profile: Calaoan Ancestral DomainIndomitable RakoОценок пока нет

- Group 6 - Katipunan PamphletДокумент2 страницыGroup 6 - Katipunan PamphletKirstelle SarabilloОценок пока нет

- REGION 12 Seph TuveraДокумент10 страницREGION 12 Seph TuveraJoseph Gadiano Tuvera IОценок пока нет

- MANSAKA, TERURAY, TBOLI, HIGAONON AND SUBANON TRIBESДокумент6 страницMANSAKA, TERURAY, TBOLI, HIGAONON AND SUBANON TRIBESjs cyberzoneОценок пока нет

- The Game of Naming: A Case of The Butuanon Language and Its Speakers in The PhilippinesДокумент21 страницаThe Game of Naming: A Case of The Butuanon Language and Its Speakers in The PhilippinesAbby GailОценок пока нет

- BatanesДокумент16 страницBatanesJohn Carlo AdranedaОценок пока нет

- Applai - Western Mountain Province Which Is Composed ofДокумент29 страницApplai - Western Mountain Province Which Is Composed ofErika mae DPОценок пока нет

- Analysis On The Proclamation of The Philippine IndependenceДокумент3 страницыAnalysis On The Proclamation of The Philippine IndependenceMikaela Joy PerezОценок пока нет

- Philippine History Reviewer: Henry Otley Beyer DawnmenДокумент74 страницыPhilippine History Reviewer: Henry Otley Beyer DawnmenFrans Caroline SalvadorОценок пока нет

- LIT ReportДокумент60 страницLIT ReportDanmar Arteta100% (1)

- IFUGAOДокумент16 страницIFUGAOHachiima McreishiОценок пока нет

- How Cagayan De Oro Got Its Name - The Origin of the City's NameДокумент2 страницыHow Cagayan De Oro Got Its Name - The Origin of the City's NameShiloh MarceloОценок пока нет

- Francisco FrondaДокумент2 страницыFrancisco FrondaAva BarramedaОценок пока нет

- Marikina's History and EvolutionДокумент27 страницMarikina's History and EvolutionRuen LomoОценок пока нет

- Jimenez, Shemeber O. Villanueva, Jaymarose B. 2bam BДокумент4 страницыJimenez, Shemeber O. Villanueva, Jaymarose B. 2bam BJaymarose VillanuevaОценок пока нет

- History ProkДокумент28 страницHistory ProkSome SpecieОценок пока нет

- Siquijor Province: An OverviewДокумент31 страницаSiquijor Province: An OverviewEli S. Eo67% (3)

- Issues and Events During Rizal's Time in The PhilippinesДокумент25 страницIssues and Events During Rizal's Time in The PhilippinesMa. Jean Rose DegamonОценок пока нет

- Moncada, Tarlac: A Brief HistoryДокумент5 страницMoncada, Tarlac: A Brief HistoryLisa MarshОценок пока нет

- PHILHIS Executive Summary - EditedДокумент7 страницPHILHIS Executive Summary - EditedMaxy Bariacto100% (1)

- DarangenДокумент1 страницаDarangenNatsya zaira100% (1)

- Davao Region Travel Guide: Top Attractions, Activities & Things to DoДокумент25 страницDavao Region Travel Guide: Top Attractions, Activities & Things to DoRonnie VillarminoОценок пока нет

- Manunggul Jar Written Report To Be SubmitДокумент3 страницыManunggul Jar Written Report To Be SubmitShaneОценок пока нет

- Tourism Stakeholders in Coron, PalawanДокумент11 страницTourism Stakeholders in Coron, PalawanDevie Filasol100% (1)

- Ibaloi ConversationДокумент92 страницыIbaloi ConversationPeter Pitas DalocdocОценок пока нет

- Lumad Cultures of MindanaoДокумент2 страницыLumad Cultures of Mindanaojxnnx sakuraОценок пока нет

- CUSTOMS OF THE TAGALOGS: A HISTORICAL ACCOUNTДокумент14 страницCUSTOMS OF THE TAGALOGS: A HISTORICAL ACCOUNTJan Arlyn Juanico100% (1)

- History of Laoag City as the Capital of Ilocos NorteДокумент3 страницыHistory of Laoag City as the Capital of Ilocos NorteFleur LynaeОценок пока нет

- Philippine HistoryДокумент13 страницPhilippine HistoryHanna Relator DolorОценок пока нет

- Delayed Development of Filipino NationalismДокумент6 страницDelayed Development of Filipino NationalismRUSSEL MAE CATIMBANGОценок пока нет

- Kapampangan people: Philippines' 7th largest ethnolinguistic groupДокумент3 страницыKapampangan people: Philippines' 7th largest ethnolinguistic groupmarlynОценок пока нет

- Philippine Folk Dance History PDFДокумент2 страницыPhilippine Folk Dance History PDFJohn Paul Ta Pham80% (5)

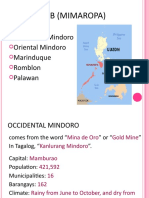

- Region Iv-B (Mimaropa) : Occidental Mindoro Oriental Mindoro Marinduque Romblon PalawanДокумент21 страницаRegion Iv-B (Mimaropa) : Occidental Mindoro Oriental Mindoro Marinduque Romblon Palawankbunnyy100% (1)

- Talaandig's Way of LivingДокумент19 страницTalaandig's Way of LivingKarl Lois CharlonОценок пока нет

- Indigenous Science and Technology in The PhilippinesДокумент15 страницIndigenous Science and Technology in The Philippinesjohn alexander olvidoОценок пока нет

- DirectionsДокумент20 страницDirectionsVhince PiscoОценок пока нет

- The Kurgan Civilization Hypothesis: CASS-DELL History of English Langauge (EL 111)Документ1 страницаThe Kurgan Civilization Hypothesis: CASS-DELL History of English Langauge (EL 111)Hannahclaire DelacruzОценок пока нет

- Heritage of CaviteДокумент61 страницаHeritage of CaviteAdrian GonzaloОценок пока нет

- Research Article: Old Sagay, Sagay City, Negros Old Sagay, Sagay City, Negros Occidental, PhilippinesДокумент31 страницаResearch Article: Old Sagay, Sagay City, Negros Old Sagay, Sagay City, Negros Occidental, PhilippinesLuhenОценок пока нет

- Ancestors Life and The Way of Living ReportДокумент26 страницAncestors Life and The Way of Living ReportAndrealyn Gevero IsiderioОценок пока нет

- Explore Cagayan Valley's ProvincesДокумент33 страницыExplore Cagayan Valley's ProvincesSenile L. Entropy67% (6)

- First Mass in the Philippines DebateДокумент14 страницFirst Mass in the Philippines Debatewhen jimin stares at your soulОценок пока нет

- Mamanwa-WPS OfficeДокумент5 страницMamanwa-WPS OfficeScaireОценок пока нет

- Term Paper Intro-RefДокумент10 страницTerm Paper Intro-RefShiela Mae AparecioОценок пока нет

- 24 DialectsДокумент7 страниц24 DialectsHannah Dorothy MalabananОценок пока нет

- Shrines in The PhilippinesДокумент41 страницаShrines in The PhilippinesAngelo RoqueОценок пока нет

- Ti Bajssít Ajkáyo NaljjajjegénjДокумент8 страницTi Bajssít Ajkáyo NaljjajjegénjDennis ValdezОценок пока нет

- IccДокумент10 страницIccAndrew Von SoteroОценок пока нет

- REMEMBERING THE HISTORIC TRIANGULAR WORLD OF SOUTHEAST ASIAДокумент10 страницREMEMBERING THE HISTORIC TRIANGULAR WORLD OF SOUTHEAST ASIAWilvyn TantongcoОценок пока нет

- MMW NotesДокумент3 страницыMMW NotesAngeli Kyle KaabayОценок пока нет

- List of English Words of Philippine Origin WikipediaДокумент2 страницыList of English Words of Philippine Origin WikipediaPaulAnthonyОценок пока нет

- 1.4.3 Roof Systems: Reinforced Concrete Roof SlabsДокумент4 страницы1.4.3 Roof Systems: Reinforced Concrete Roof SlabsMark Anthony FauneОценок пока нет

- AR33 Stair SystemsДокумент15 страницAR33 Stair SystemsMark Anthony FauneОценок пока нет

- Population Growth and Economic Development The Case of China (Balde, Faune, Manaog)Документ13 страницPopulation Growth and Economic Development The Case of China (Balde, Faune, Manaog)Mark Anthony FauneОценок пока нет

- Polyprotic AcidsДокумент3 страницыPolyprotic AcidsMark Anthony FauneОценок пока нет

- Notes On Arkiyoloji 1Документ2 страницыNotes On Arkiyoloji 1Mark Anthony FauneОценок пока нет

- Petroleum ProcessingДокумент22 страницыPetroleum ProcessingMark Anthony FauneОценок пока нет

- 2 Long Test, Computer Science 4: Task 1: Subnet The Address SpaceДокумент4 страницы2 Long Test, Computer Science 4: Task 1: Subnet The Address SpaceMark Anthony FauneОценок пока нет

- Experimental AutoethnographyДокумент18 страницExperimental AutoethnographyMark Anthony FauneОценок пока нет

- Benefits of Federalism and Parliamentary Government for the PhilippinesДокумент19 страницBenefits of Federalism and Parliamentary Government for the PhilippinesfranzgabrielimperialОценок пока нет

- As Yet An Asian Flavor Does Not ExistДокумент3 страницыAs Yet An Asian Flavor Does Not ExistMark Anthony FauneОценок пока нет

- Bark Cloth Beater of Arku CaveДокумент5 страницBark Cloth Beater of Arku CaveMark Anthony FauneОценок пока нет

- Archaeological Investigation of Sagel Cave at Maitum, Sarangani Province, Southern Mindanao, PhilippinesДокумент24 страницыArchaeological Investigation of Sagel Cave at Maitum, Sarangani Province, Southern Mindanao, PhilippinesMark Anthony FauneОценок пока нет

- Edgar Allan Poe - Cask of Amontillado, TheДокумент9 страницEdgar Allan Poe - Cask of Amontillado, TheMaria MafteiuОценок пока нет

- Commodities and Culture - FISKEДокумент15 страницCommodities and Culture - FISKEDaniel Orizaga DoguimОценок пока нет

- Experiment No. 2Документ3 страницыExperiment No. 2Mark Anthony FauneОценок пока нет

- Presents World of Warcraft Gold Strategy Guide Learn How To Make Gold Like A ProДокумент49 страницPresents World of Warcraft Gold Strategy Guide Learn How To Make Gold Like A Proapi-3814950Оценок пока нет

- Brochure Aquaculture ID Plug en Play Hatchery SystemsДокумент20 страницBrochure Aquaculture ID Plug en Play Hatchery SystemsAl SantosОценок пока нет

- YPR models optimize fishery yieldДокумент39 страницYPR models optimize fishery yieldJingle FanОценок пока нет

- Philippine National Standard For Dried Sea CucumberДокумент15 страницPhilippine National Standard For Dried Sea CucumberKevin YaptencoОценок пока нет

- Philippine Commercial Fishing Industry Business PlanДокумент38 страницPhilippine Commercial Fishing Industry Business Plandanah75% (8)

- Accomplishment ReportДокумент6 страницAccomplishment ReportTumanguil Quilang RubenОценок пока нет

- Report on Gold Mining and ExtractionДокумент4 страницыReport on Gold Mining and Extractioninnocence_whiteОценок пока нет

- Authentic Rogan JoshДокумент6 страницAuthentic Rogan JoshPedro ZackoОценок пока нет

- Fish Farming PresentationДокумент11 страницFish Farming PresentationRahid KhanОценок пока нет

- Coach's Pizza & Ribs MenuДокумент6 страницCoach's Pizza & Ribs MenuwhiskeydiqkОценок пока нет

- The Effects of Environmental Stress On Outbreaks of Infectious Diseases of FishesДокумент12 страницThe Effects of Environmental Stress On Outbreaks of Infectious Diseases of FishesRodolfo Angulo OlaisОценок пока нет

- Caulerpa VC Report 2011 - FinalДокумент20 страницCaulerpa VC Report 2011 - FinalGuarino Ken JustinОценок пока нет

- 1.1 14-26 Willow Beach NFH - FY 2014 ReportДокумент2 страницы1.1 14-26 Willow Beach NFH - FY 2014 ReportHeather SmathersОценок пока нет

- Vertebrate Worksheet AnswersДокумент5 страницVertebrate Worksheet AnswersPak RisОценок пока нет

- Sea Stats - Blue CrabДокумент4 страницыSea Stats - Blue CrabFlorida Fish and Wildlife Conservation CommissionОценок пока нет

- Diving GT Barrier Reef 2 Swain Pompey v1 m56577569830512321Документ5 страницDiving GT Barrier Reef 2 Swain Pompey v1 m56577569830512321Kathan GandhiОценок пока нет

- Float Rig Guide - TraditionalFishingFloats - Co.ukДокумент19 страницFloat Rig Guide - TraditionalFishingFloats - Co.ukPaul Duffield100% (1)

- Fish Landing Project BrieferДокумент2 страницыFish Landing Project Brieferapi-306064982100% (1)

- Healthy Mass 3000Документ99 страницHealthy Mass 3000Alex Hladun0% (1)

- Meal HacksДокумент12 страницMeal HacksJuvhyl Ann Gingco100% (1)

- Scoring Rubrics: Curing, Salting & Smoking Fermentation and PicklingДокумент2 страницыScoring Rubrics: Curing, Salting & Smoking Fermentation and PicklingNoah R. Lobitana100% (8)

- Rainwater Harvesting and Artificial Recharge - UnescoДокумент22 страницыRainwater Harvesting and Artificial Recharge - UnescoGreen Action Sustainable Technology GroupОценок пока нет

- KalinagosДокумент14 страницKalinagosJoshua LawrenceОценок пока нет

- Delicious Black Bean BurritosДокумент2 страницыDelicious Black Bean BurritosNga WangОценок пока нет

- Ruzba Class 2Документ6 страницRuzba Class 2negalamadnОценок пока нет

- Founding of New France Settlement and Colonization PowerpointДокумент17 страницFounding of New France Settlement and Colonization Powerpointapi-295328704Оценок пока нет

- The American Journey: Activity WorkbookДокумент80 страницThe American Journey: Activity WorkbookCaroline Brown0% (3)

- 35 - Better Freshwater Fish-Farming PDFДокумент72 страницы35 - Better Freshwater Fish-Farming PDFSeyha L. AgriFoodОценок пока нет

- Polyamines in Foods - Development of A Food DatabaseДокумент15 страницPolyamines in Foods - Development of A Food Databaseoffice8187Оценок пока нет

- Report TextДокумент10 страницReport Textduz thaОценок пока нет