Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Henthorn V Fraser (1892) - 2-Ch.-27

Загружено:

nabila14Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Henthorn V Fraser (1892) - 2-Ch.-27

Загружено:

nabila14Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

2 Oh.

CHANCEEY DIVISION.

HENTHOEN v. FEASEE.

[1891 H. 226.]

Contract by LettersAcceptance of Offer by PostTime of AcceptanceWith

drawal of Offer.

H., who lived at Birkenhead, called at the office of a land society in

Liverpool, to negotiate for the purchase of some houses helonging to them.

The secretary signed and handed to him a note giving him the option of

purchase for fourteen days at 750. On the next day the secretary posted

to H. a withdrawal of the offer. This withdrawal was posted between 12

and 1 o'clock, and did not reach Birkenhead till after 5 P.M. In the mean

time H. had, at 3.50 P.M., posted to the secretary an unconditional accept

ance of the offer, which was delivered in Liverpool after the society's office

had closed, and was opened hy the secretary on the following morning:

Held, that where the circumstances under which an offer is made are

such that it must have been within the contemplation of the parties that,

according to the ordinary usages of mankind, the post might be used as a

means of communicating the acceptance of it, the acceptance is complete

as soon as it is posted.

Held, that in the present case, as the parties lived in different towns, an

acceptance by post must have been within their contemplation, although

the offer was not made by post.

Held, that a revocation of an offer is of no effect until brought to the

mind of the person to whom the offer was made, and that therefore a

revocation sent by post does not operate from the time of posting it.

Held, therefore (reversing the decision of the Vice-Chancellor of the

County Palatine), that a binding contract was made on the posting of H.'sacceptance, that the revocation of the offer was too late, and that H. was

entitled to specific performance.

IN 1891 the Plaintiff was desirous of purchasing from the

Huslcisson Benefit Building Society certain houses in Flamank

Street, Birkenhead. In May he, at the office of the society in

Chanel Street, Liverpool, signed a memorandum drawn up by the

secretary, offering 600 for the property, which offer was declined

by the directors; and on the 1st of July he made in the same

way an offer of 700, which was also declined. On the 7th of

July he again called at the office, and the secretary verbally

offered to sell to him for 750. This offer was reduced intowriting, and was as follows :

" I hereby give you the refusal of the Flamank Street property

at 750 for fourteen days."

28

CHANCERY DIVISION.

t.A.

J^

HENTHORN

FRASER.

[1892]

The secretary, after signing this, handed it to the Plaintiff,

who took it away with him for consideration.

On the morning of the 8th another person called at the office,

and offered 760 for the property, which was accepted, and a

contract for purchase signed, subject to a condition for avoiding

it if the society found that they could not withdraw from the

offer to the Plaintiff.

Between 12 and 1 o'clock on that day the secretary posted to

the Plaintiff, who resided in Birkenhead, the following l e t t e r :

i " Please take notice that my letter to you of the 7th instant,

giving you the option of purchasing the property, Flamank Street,

Birkenhead, for 750, in fourteen days, is withdrawn, and the

offer cancelled."

This letter, it appeared, was delivered at the Plaintiff's address

between 5 and 6 in the evening, but, as he was out, did not

reach his hands till about 8 o'clock.

On the same 8th of July the Plaintiff's solicitor, by the Plain

tiff's direction, wrote to the secretary as follows:

" I am instructed by Mr. James Henthorn to write you, and

accept your offer to sell the property, 1 to 17, Flamank Street,

Birkenhead, at the price of 750. Kindly have contract pre

pared and forwarded to me."

This letter was addressed to the society's office, and was posted

in Birkenhead at 3.50 P.M., was delivered at 8.30 P.M. after the

closing of the office, and was received by the secretary on the fol

lowing morning. The secretary replied, stating that the society's

offer had been withdrawn.

The Plaintiff brought this actiori in the Court of the County

Palatine for specific performance. The Vice-Chancellor dis

missed the action, and the Plaintiff appealed.

Farwell, Q.C., and T. B. Hughes, for the a p p e a l :

We say that a binding contract was made when the Plaintiff's

letter of acceptance was posted: Dunlop v. Higgins (1); Harris's

Case (2); Adams v. Lindsell (3). We do not dispute that, though

(1) 1 H. L. C. 381.

(2) Law Eep. 7 Ch. 587.

(3) 1 B. & Al. 681.

2Ch.

CHANCEEY DIVISION.

the option was given for fourteen days, it could be withdrawn

within that time: Dickinson v. Dodds (1); but if a binding con

tract is entered into, there cannot be a withdrawal. Where an

acceptance is to be signified by doing some particular thing, as

soon as that particular thing is done there is a contract: Brogden

v. Metropolitan'RailwayCompany (2). Where it must be in the

contemplation of the parties that an answer will be sent by post,

the posting an acceptance makes a contract. In the case of

Household Fire and Carriage Accident Insurance Company v.

Grant (3) it was considered that, according to the usages of

mankind, an acceptance would be sent by post; and it was

held that posting an acceptance made a contract, though the

acceptance was never received. Here, as the parties lived in

different towns, it was to be expected that the Plaintiff would

post his answer. In Byrne v. Van Tienhoven (4) a withdrawal

was held too late which was not received till after the offer had

been accepted, though it was posted before the acceptance ; and

so in Stevenson v. McLean (5) it was held that a withdrawal of an

offer was of no effect until it reached the other party.

Neville, Q.C., and P. 0. Lawrence, for the Defendant:

We submit that the Vice-Chancellor has drawn a correct

inferencethat there was no authority to accept by post; and

if that be so, the acceptance will not date from the posting.

Dunlop v. Higgins (6) went on the ground that it was the under

standing of both parties that an answer should be sent by post.

In Brogden v. Metropolitan Railway Company, Lord Blackburn

puts it on the ground " that where it is expressly or impliedly

stated in the offer that you may accept the offer by posting a

letter, the moment you post the letter the offer is accepted." It

would be very inconvenient to hold the post admissible in all

cases. Here, Liverpool and Birltenliead are at such a short distance

from each other, that it cannot be considered that the Plaintiff

had an authority to reply by post. If the offer had been sent by

post, that would, no doubt, be held to give an authority to reply

(1) 2 Ch. D. 463.

(2) 2 App. Cas. 666, 691.

(3) 4 Ex. D. 216.

(4) 5 C. P. D. 314.

(5) 5 Q. B. D. 346.

(6) 1 H. L. C. 381.

30

CHANCERY DIVISION.

[1892]

C.A.

1892

by post; but the offer was delivered by hand to the Plaintiff,

who was in the habit of calling at the Defendants' office, and

HENTHOBN lived only at a short distance, so that authority to reply by post

FBASEE

cannot be inferred. The post is not prohibited; the acceptance

may be sent in any way; but, unless sending it by post was

authorized, it is inoperative till it is received. Suppose, imme

diately after posting the acceptance, the Plaintiff had gone to

the office and retracted it, surely he would have been free.

is not clear that he would, after

sending an acceptance in such a way that he could not prevent

its reaching the other party. Possibly a case where the question

is as to the date from which an acceptance which has been re

ceived is operative may not stand on precisely the same footing

as one where the question is whether the person making the

offer is bound, though the acceptance has never been received

a t all. More evidence of authority to accept by post may be

required in the latter case than in the former.]

[LORD H E K S C H E L L : I t

Dickinson v. Dodds (1) shews that a binding contract to sell to

another person may be made while an offer is pending, and that

it will be a withdrawal of the offer.

[LORD HEKSCHELL : I n that case the person to whom the

offer was made knew of the sale before he sent his acceptance.]

Farwell, in reply.

1892. March 26.

LOED HEKSCHELL

This is an action for the specific performance of a contract to

sell to the Plaintiff certain house property situate in FlamanJc

Street, Birkenhead. The action was tried before the Vice-Chan

cellor of the County Palatine of Lancashire, who gave judgment

for the Defendants. On the 7th of July, 1891, the secretary of

the building society whom the Defendants represent handed to

the Plaintiff, in the office of the society at Liverpool, a letter in

these t e r m s : " I hereby give you the refusal of the FlamanJc

Street property at 750 for fourteen days." I t appears that the

Plaintiff had been for some time in negotiation for the property,

(1) 2 Ch. D. 463.

2 Ch.

CHANCEBY DIVISION.

31

and had on two previous occasions made offers for the purchase

0. A.

of it, which were not accepted by the society. These offers were

1892

made by means of letters, written by the secretary in the office HESTHORN

of the society, and signed by the Plaintiff there. The Plaintiff ^RISER

resided in Birkenhead, and he took away with him to that town T ,

'

Lord Herschell.

the letter of the 7th of July containing the offer of the society.

On the 8th of July a letter was posted in Birkenhead at 3.50 P.M.,

written by his solicitor, accepting on his behalf the offer to sell

the property at 750. This letter was not received at the De

fendants' office until 8.30 P.M., after office hours, the office being

closed at 6 o'clock. On the same day a letter was addressed to

the Plaintiff by the secretary of the building society in these

terms :" Please take notice that my letter to you of the 7th

inst. giving you the option of purchasing the property, Flamanh

Street, Birkenhead, for 750, in fourteen days, is withdrawn and

the offer cancelled." This letter was posted in Liverpool between

12 and 1 P.M., and was received in Birkenhead at 5.30 P.M. It

will thus be seen that it was received before the Plaintiffs letter

of acceptance had reached Liverpool, but after it had been posted.

One other fact only need be stated. On the 8th of July the

secretary of the building society sold the same premises to

Mr. Miller for the sum of 760, but the receipt for the deposit

paid in respect of the purchase stated that it was subject to

being able to withdraw the letter to Mr. Henthom giving him

fourteen days' option of purchase.

If the acceptance by the Plaintiff of the Defendants' offer is

to be treated as complete at the time the letter containing it was

posted, I can entertain no doubt that the society's attempted

revocation of the offer was wholly ineffectual. I think that a

person who has made an offer must be considered as continuously

making it until he has brought to the knowledge of the person

to whom it was made that it is withdrawn. This seems to me to

be in accordance with the reasoning of the Court of King's

Bench in the case of Adams v. Lindsell (1), which was approved

by the Lord Chancellor in Bunlop v. Biggins (2), and also with

the opinion of Lord Justice Mellish in Harris's Case (3). The

(1) 1 B. & Al. 681.

(2) 1 H. L. C. 381, 399.

(3) Law Eep. 7 Ch. 587.

32

CHANCERY DIVISION.

C. A.

1892

[1892]

very point was decided in the case of Byrne v. Van Tienhoven (1)

by Lord Justice Lindley, and his decision was subsequently folHEXTHOKS lowed by Mr. Justice Lush. The grounds upon which it has

FBASEH

keen k e ^ that the acceptance of an offer is complete when it is

c h ; ] posted have, I think, no application to the revocation or modiflcation of an offer. These can be no more effectual than the offer

itself, unless brought to the mind of the person to whom the

offer is made. But it is contended on behalf of the. Defendants

that the acceptance was complete only when received by them

and not on the letter being posted. It cannot, of course, be denied,

after the decision in Dunlop v. Higgins (2) in the House of

Lords, that, where an offer has been made through the medium

of the post, the contract is complete as soon as the acceptance of

the offer is posted, but that decision is said to be inapplicable

here, inasmuch as the letter containing the offer was not sent by

post to Birkenhead, but handed to the Plaintiff in the Defen

dants' office at Liverpool. The question therefore arises in what

circumstances the acceptance of an offer is to be regarded as

complete as soon as it is posted. In the case of the Household

Fire and Carriage Accident Insurance Company v. Grant (8), Lord

Justice Baggallay said (4): " I think that the principle established

in Dunlop v. Biggins is limited in its application to cases in

which by reason of general usage, or of the relations between

the parties to any particular transactions, or of the terms in

which the offer is made, the acceptance of such offer by a letter

through the post is expressly or impliedly authorized." And in

the same case Lord Justice Tliesiger based his judgment (5) on the

defendant having made an application for shares under circum

stances "from which it must be implied that he authorized the com

pany, in the event of their allotting to him the shares applied for,

to send the notice of allotment by post." The facts of that case

were that the defendant had, in Swansea, where he resided, handed

a letter of application to an agent of the company, their place of

business being situate in London. It was from these circumstances

that the Lords Justices implied an authority to the company to

(1) 5 C. P. D. 344.

(2) 1 H. L. C. 381.

[ (3) 4 Ex. D. 216.

(4) Ibid. 227.

(5) 4 Ex. D. 218.

2 Ch.

CHANCERY DIVISION.

accept the defendant's offer to take shares through the medium

of the post. Applying the law thus laid down by the Court of

Appeal, I think in the present case an authority to accept by

post must be implied. Although the Plaintiff received the offer

at the Defendants' office in Liverpool, he resided in another town,

*

and it must have been in contemplation that he would take the

offer, which by its terms was to remain open for some days, with

him to his place of residence, and those who made the offer must

have known that it would be according to the ordinary usages of

mankind that if he accepted it he should communicate his

acceptance by means of the post. I am not sure that I should

myself have regarded the doctrine that an acceptance is complete

as soon as the letter containing it is posted as resting upon an

implied authority by the person making the offer to the person

receiving it to accept by those means. I t strikes me as some

what artificial to speak of the person to whom the offer is made

as having the implied authority of the other party to send his

acceptance by post. He needs no authority to transmit the

acceptance through any particular channel; he may select what

means he pleases, the Post Office no less than any other. The

only effect of the supposed authority is to make the acceptance

complete so soon as it is posted, and authority will obviously be

implied only when the tribunal considers that it is a case in

which this result ought to be reached. I should prefer to state

the rule t h u s : Where the circumstances are such that it must

have been within the contemplation of the parties that, accord

ing to the ordinary usages of mankind, the post might be used

as a means of communicating the acceptance of an offer, the

acceptance is complete as soon as it is posted. I t matters not

in which way the proposition be stated, the present case is in

either view within it. The learned Vice-Chancellor appears to

have based his decision to some extent on the fact that before

the acceptance was posted the Defendants had sold the property

to another person. The case of Dickinson v. Bodds (1) was

relied upon in support of that defence. I n that case, however,

1 he plaintiff knew of the subsequent sale before he accepted the

offer, which, in my judgment, distinguishes it entirely from the

(1) 2 Ch. D. 463.

VOL. II. 1892.

B

1

33

0. A.

1892

HENTHORN

_ *

Lord Herschell.

CHANCERY DIVISION.

[1892]

present case. JFor the reasons I have given, I think the judg

ment must be reversed and the usual decree for specific performance made. The. Eespondents must pay the costs of the

appeal and of the action.

LINDLET,

L.J.:

I quite concur. I am not prepared to accede to the argument

that because the offer was not made by post there was no autho

rity to send an acceptance by post, and the Vice-Chancellor, in

my opinion, fell into a mistake by acceding to it.

KAY,

L.J. :

On the 7th of July, 1891, the Defendants gave to the Plaintiff,

who was then in their office in Liverpool, an offer in writing to

sell him certain real property at Birkenhead, where the Plaintiff

resided. The Plaintiff had been on several previous occasions

at their office on this or like business. He was not able to

write beyond signing his name. On the 8th of July his solicitor

wrote by his direction accepting the offer. This letter was

posted at 3.50 P.M., and arrived at 8.30 the same evening.

This was after office hours, and it was not opened till 10 o'clock

next morning. In the meantime the Defendants wrote with

drawing their offer on the same 8th of July, and posted their

letter between 12 and 1 P.M. This was received at 5.30 the

same evening. On the same 8th of July the Defendants entered

into a contract to sell the same property to another person

with an express condition if they were able to withdraw their

offer to the Plaintiff.

The question is, was the withdrawal in time or too late.

Dunlop v. Biggins (1) has decided that, where a letter sent by

post was a proper mode of acceptance, the contract was complete

from the time that the letter was posted. In that case the

letter was actually received, though, by fault of the Post Office,

there was some delay in its transmission. Upon receipt of it,

the offer was withdrawn. The question was the same as in the

present case, except that the withdrawal was after the actual

(I) 1 H. L. C. 381.

2Ch:'

CHANCERY DIVISION.

35

receipt? of the acceptance which was treated as being too late. It

O. A.

was held that, by posting the letter in due time, the party by

1892

the usage of trade had done all that he was bound to do. He HESTHORN

couldnot be responsible for the delay of the Post Office in deliver- F R * g E R

ing the letter, and therefore there was from the time of the

\

}

\

,

I

'

Kay, L.J.

posting a valid acceptance. It might have still been doubtful

whether posting a letter of acceptance in time, would amount to

an acceptance if the letter was never received. The ordinary

rule is, that to constitute a contract there must be an offer, an

acceptance, and a communication of that acceptance to the

person making the offer: per Lord Blackburn, in Brogden v.

Metropolitan Railway Company (1); and see per Lord Bramwell (2).

It may be that where the communication is in fact received, the

contract may date back to the time of posting the acceptance,

but there is considerable reason for holding that if never received

the posting might be treated as a nullity. The point was so

decided in British and American Telegraph Company v. Colson (3);

and see the judgment of Lord Bramwell in Household Fire and

Carriage Accident Insurance Company v. Grant. However, in

the last-mentioned case, which is a decision binding upon this

Court, the Court of Appeal, Bramwell, L.J., dissenting, held,

that the posting of a letter of allotment in answer to an ap

plication for shares constituted a binding contract to take the

shares though the letter of allotment was not received. In his

judgment, Thesiger, L.J., refers to the cases in which the deci

sion in Dunlop v. Higgins (4) has -been explained by saying that

the Post Office was treated as the common agent of both con

tracting parties. That reason is not satisfactory. The Post

Office are only carriers between them. They are agents to

convey the communication, not to receive it. The communica

tion is not made to the Post Office, but by their agency as

carriers. The difference is between saying "Tell my agent A.,

if you accept," and " Send your answer to me by A." In the

former case A. is to be the intelligent recipient of the accept

ance, in the latter- he is only to convey the communication to the

person making the offer which he may do by a letter, knowing

(1) 2 App. Cas. 692.

' (2) 4 Ex. D. 233.

(3) Law Eep. 6 Ex. 108.

(4) 1 H. L. C. 381.

D2

36

CHANCEBY DIVISION.

C- A.

1892

HENTHOBN

FBASEB.

i~^ J #

[1892]

nothiDg of its contents. The Post Office are only agents in the

latter sense. All that Dunlop v. Biggins (1) decided was, that

the acceptor of the offer haying properly posted his acceptance,

was n

t responsible for the delay of the Post Office in delivering

i t ; so that after receipt the said party could not rescind on the

ground of that delay. I cannot help thinking that the decision

has been treated as going much further than the House of Lords

intended. Baggallay, L.J., in his judgment in Household Fire

and Carriage Accident Insurance Company v. Grant (2), treatsit as applicable " t o cases in which by reason of general usage,

or of the relations between the parties to any particular trans

actions, or of the terms in which the offer is made, the acceptance

of such offer by a letter through the post is expressly or im

pliedly authorized." If for authorized the word "contemplated"

is substituted, I should be disposed to agree with this dictum.

But I would rather express it t h u s : " Posting an acceptance of

an offer may be sufficient where it can fairly be inferred from

the circumstances of the case that the acceptance might be sent

by post."

Is that a proper inference in the present case ? I think it is.

One party resided in Liverpool, the other in Birkenhead. Theacceptance would be expected to be in writing, the subject of

purchase being real estate. These and the other circumstances

to which I have alluded, in my opinion, warrant the inference

that both parties contemplated that a letter sent by post was a

mode by which the acceptance might be communicated. I think,

therefore, that we are bound by authority to hold, that the contract.

was complete at 3.50 P.M. on the 8th of July, when the letter of

acceptance was posted, and before the letter of withdrawal wasreceived.

Then what was the effect of the withdrawal by the letter posted

between 12 and 1 the same day, and received in the evening ?

Did that take effect from the time of posting ? I t has never

been held that this doctrine applies to a letter withdrawing the

offer. Take the cases alluded to by Lord Bramwell in the

Household Fire and Carriage Accident Insurance Company v.

Grant (3). A notice by a tenant to quit can have no operation

(1) 1 H. L. C. 381.

(2) 4 Ex. D. 227.

(3) 4 Ex. D. 234.

2Ch.

CHANCERY DIVISION.

till it comes to the actual knowledge of the person to whom it

is addressed. An offer to sell is nothing until it is actually

received. No doubt there is the seeming anomaly pointed out

by Lord Bramwell that the same letter might contain an accept

ance, and also such a notice or offer as to other property, and

that when posted it would be effectual as to the acceptance, and

not as to the notice or offer. But the anomaly, if it be one,

arises from the different nature of the two communications. As

to the acceptance, if it was contemplated that it might be sent

by post, the acceptor, in Lord Cottenham's language, has done all

that he was bound to do by posting the letter, but this cannot be

said as to the notice of withdrawal. That was not a contem

plated proceeding. The person withdrawing was bound to bring

his change of purpose to the knowledge of the said party, and as

this was not done in this case till after the letter of acceptance

was posted, I am of opinion that it was too late.

The point has been so decided in two cases: Byrne v. Van

Tienhoven (1), and Stevenson v. McLean (2), and I agree with

those decisions.

Solicitors : G. Balby, Birkenhead; Miller & Williamson, Liver

pool.

(1) 5 C. P. D. 344.

(2) 5 Q. B. D. 346.

H. C. J.

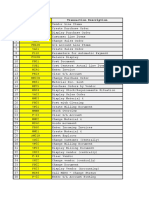

Вам также может понравиться

- Storer V Manchester City Council - (1974) 3 PDFДокумент8 страницStorer V Manchester City Council - (1974) 3 PDFYee Sook YingОценок пока нет

- HYDE V WRENCH (1840) 3 Beav-1Документ2 страницыHYDE V WRENCH (1840) 3 Beav-1Karen MalsОценок пока нет

- Amalgamated Investment and Property Co LTD V John Walker & Sons LTDДокумент12 страницAmalgamated Investment and Property Co LTD V John Walker & Sons LTDthinkkim100% (1)

- Letang v. Cooper, (1965) 1 QB 232Документ10 страницLetang v. Cooper, (1965) 1 QB 232VISHAL PATELОценок пока нет

- Dick Bentley Productions Ltd. and Another V Harold Smith (Motors) Ltd.Документ7 страницDick Bentley Productions Ltd. and Another V Harold Smith (Motors) Ltd.Squall LeonhartОценок пока нет

- Lambton V MellishДокумент3 страницыLambton V Mellishmirmuiz2993Оценок пока нет

- Labour Law ContinuationДокумент15 страницLabour Law Continuationيونوس إبرحيم100% (1)

- Doctrine of Conversion PDFДокумент42 страницыDoctrine of Conversion PDFAnjola AlakabaОценок пока нет

- Intention To Create Legal Relations Cases UWIДокумент16 страницIntention To Create Legal Relations Cases UWIJoyann Goodridge100% (2)

- Midland Bank Trust Co LTD and Another V Green (1981) AC 513Документ20 страницMidland Bank Trust Co LTD and Another V Green (1981) AC 513Saleh Al Tamami100% (1)

- Sierra Leone Oxygen Factory LTD V PB Pyne Bailey 10 May 1974Документ12 страницSierra Leone Oxygen Factory LTD V PB Pyne Bailey 10 May 1974Komba JohnОценок пока нет

- The University of Zambia School of Law: Name:Tanaka MaukaДокумент12 страницThe University of Zambia School of Law: Name:Tanaka MaukaTanaka MaukaОценок пока нет

- Cutter V PowellДокумент11 страницCutter V PowellEbby FirdaosОценок пока нет

- The - Cape - Brandy - Syndicate - V - The - Commissioner Inland RevenueДокумент19 страницThe - Cape - Brandy - Syndicate - V - The - Commissioner Inland RevenueNoel100% (1)

- Immovable Property I: Pledgeof Land Under Customary LawДокумент9 страницImmovable Property I: Pledgeof Land Under Customary LawMaame BaidooОценок пока нет

- Criminal LiabilityДокумент66 страницCriminal LiabilityMaka T Foroma100% (2)

- Intention To Create A Legal RelationshipДокумент1 страницаIntention To Create A Legal RelationshipShalim JacobОценок пока нет

- Appiah V Mensah & Others 1 GLR 342-351Документ9 страницAppiah V Mensah & Others 1 GLR 342-351Solomon BoatengОценок пока нет

- British Airways V. Attorney-General CaseДокумент1 страницаBritish Airways V. Attorney-General CaseMaameОценок пока нет

- Court Jurisdiction Case StudyДокумент2 страницыCourt Jurisdiction Case StudyNahmyОценок пока нет

- Deconstructing Rylands V FletcherДокумент20 страницDeconstructing Rylands V FletcherChristopherDowson0% (1)

- GRP 5 Family LawДокумент9 страницGRP 5 Family LawNaomi VimbaiОценок пока нет

- 073 NLR NLR V 72 C. KODEESWARAN Appellant and THE ATTORNEY GENERAL RespondentДокумент11 страниц073 NLR NLR V 72 C. KODEESWARAN Appellant and THE ATTORNEY GENERAL RespondentEdgar SenevirathnaОценок пока нет

- Waqf Under Muslim LawДокумент9 страницWaqf Under Muslim LawVaishnavi Soni100% (1)

- Hughes v. Metropolitan Railway CoДокумент10 страницHughes v. Metropolitan Railway Cogullupats50% (2)

- KSL ATP 105 PE TOPIC 6 Part 1the Advocate-Client RelationshipДокумент51 страницаKSL ATP 105 PE TOPIC 6 Part 1the Advocate-Client RelationshipCharles B G Ouma100% (1)

- Bank of Nova Scotia Vs Hellenic Mutual War Risks AUKHL910043COM137144Документ18 страницBank of Nova Scotia Vs Hellenic Mutual War Risks AUKHL910043COM137144Samaksh KhannaОценок пока нет

- MENSAH v. PENIANAДокумент11 страницMENSAH v. PENIANASolomon BoatengОценок пока нет

- Adams V LindsellДокумент1 страницаAdams V LindsellR JonОценок пока нет

- Cresswell v. Sirl (1948)Документ8 страницCresswell v. Sirl (1948)Falguni SharmaОценок пока нет

- Lecture Notes - Inchoate CrimesДокумент21 страницаLecture Notes - Inchoate CrimesAsha YadavОценок пока нет

- Lect. 3 Mens ReaДокумент15 страницLect. 3 Mens ReaNicole BoyceОценок пока нет

- Essilfie and Another v. QuarcooДокумент12 страницEssilfie and Another v. QuarcooISAAC ADUSI-POKUОценок пока нет

- Land Law - LeaseДокумент26 страницLand Law - Leasepokandi.fbОценок пока нет

- Agyentoa V OwusuДокумент3 страницыAgyentoa V OwusuMaameОценок пока нет

- Mode of Originating Process - Amendment of PleadingsДокумент35 страницMode of Originating Process - Amendment of PleadingsAmira IzzatiОценок пока нет

- Tort Law Ca 1Документ6 страницTort Law Ca 1JESSICA NAMUKONDAОценок пока нет

- Evidence CaseДокумент10 страницEvidence CasetsetenОценок пока нет

- Duty of CounselДокумент14 страницDuty of CounselKhairul Iman100% (1)

- Topic 4 Modes of Originating ProcessДокумент9 страницTopic 4 Modes of Originating ProcessJasintraswni RavichandranОценок пока нет

- .Au-Causation in Murder Cases Thabo Meli V The QueenДокумент2 страницы.Au-Causation in Murder Cases Thabo Meli V The QueenDileep ChowdaryОценок пока нет

- Topic 2 Civil Courts & Their JurisdictionДокумент7 страницTopic 2 Civil Courts & Their JurisdictionJasintraswni RavichandranОценок пока нет

- ANNIN v. THE REPUBLIC GHANAДокумент10 страницANNIN v. THE REPUBLIC GHANAdurtoОценок пока нет

- CASELAWДокумент2 страницыCASELAWValentine NgalandeОценок пока нет

- National Provincial Bank V AinsworthДокумент33 страницыNational Provincial Bank V AinsworthpeterОценок пока нет

- Assignment On ADRДокумент7 страницAssignment On ADRMozammel Hoque RajeevОценок пока нет

- Central London Property Trust LTD V High Trees House LTDДокумент7 страницCentral London Property Trust LTD V High Trees House LTDTheFeryОценок пока нет

- RYLANDS V FLETCHERДокумент5 страницRYLANDS V FLETCHERShaniel T HunterОценок пока нет

- Land Rights Versus Mineral RightsДокумент7 страницLand Rights Versus Mineral RightsMordecaiОценок пока нет

- Lecture 9 14Документ39 страницLecture 9 14marieОценок пока нет

- Punishment Case BriefsДокумент9 страницPunishment Case Briefsfauzia tahiruОценок пока нет

- Chapter 14 - AnimalsДокумент34 страницыChapter 14 - AnimalsMarkОценок пока нет

- Administrative Law CasesДокумент14 страницAdministrative Law CasesDoreen Aaron100% (1)

- The People V Chitambala (1969) ZR 142 (HC) : Zulu, Director of Public Prosecutions, For The People. Care, For The DefenceДокумент4 страницыThe People V Chitambala (1969) ZR 142 (HC) : Zulu, Director of Public Prosecutions, For The People. Care, For The DefenceGriffin chikusi100% (1)

- The Queen v. Flattery (1877) 2 Q.B.D. 410Документ4 страницыThe Queen v. Flattery (1877) 2 Q.B.D. 410Bond_James_Bond_007100% (1)

- Byrne and Co V Leon Van Tien Hoven and CoДокумент4 страницыByrne and Co V Leon Van Tien Hoven and CoShalОценок пока нет

- Hyde V Wrench (1840) 49 ER 132Документ2 страницыHyde V Wrench (1840) 49 ER 132Nerissa Zahir100% (4)

- Adams and Others V Lindsell and AnotherДокумент2 страницыAdams and Others V Lindsell and AnothersoumyaОценок пока нет

- Dickinson V Assign 2Документ13 страницDickinson V Assign 2LAVANYA SОценок пока нет

- Cape Law: Texts and Cases - Contract Law, Tort Law, and Real PropertyОт EverandCape Law: Texts and Cases - Contract Law, Tort Law, and Real PropertyОценок пока нет

- Senate Bill No. 982Документ3 страницыSenate Bill No. 982Rappler100% (1)

- Problem Set 1Документ2 страницыProblem Set 1edhuguetОценок пока нет

- Social Engineering FundamentalsДокумент13 страницSocial Engineering FundamentalsPonmanian100% (1)

- Shailendra Education Society's Arts, Commerce & Science College Shailendra Nagar, Dahisar (E), Mumbai-68Документ3 страницыShailendra Education Society's Arts, Commerce & Science College Shailendra Nagar, Dahisar (E), Mumbai-68rupalОценок пока нет

- Invoice 141Документ1 страницаInvoice 141United KingdomОценок пока нет

- M Fitra Rezeqi - 30418007 - D3TgДокумент6 страницM Fitra Rezeqi - 30418007 - D3TgNugi AshterОценок пока нет

- Fleeting Moments ZineДокумент21 страницаFleeting Moments Zineangelo knappettОценок пока нет

- Belly Dance Orientalism Transnationalism and Harem FantasyДокумент4 страницыBelly Dance Orientalism Transnationalism and Harem FantasyCinaraОценок пока нет

- Mitigate DoS Attack Using TCP Intercept On Cisco RouterДокумент4 страницыMitigate DoS Attack Using TCP Intercept On Cisco RouterAKUEОценок пока нет

- HIE GLPsДокумент6 страницHIE GLPsWilson VerardiОценок пока нет

- Strategic Management CompleteДокумент20 страницStrategic Management Completeأبو ليلىОценок пока нет

- FIRST YEAR B.TECH - 2020 Student List (MGT and CET) PDFДокумент128 страницFIRST YEAR B.TECH - 2020 Student List (MGT and CET) PDFakashОценок пока нет

- Statutory Construction NotesДокумент8 страницStatutory Construction NotesBryan Carlo D. LicudanОценок пока нет

- Bernini, and The Urban SettingДокумент21 страницаBernini, and The Urban Settingweareyoung5833Оценок пока нет

- Launch Your Organization With WebGISДокумент17 страницLaunch Your Organization With WebGISkelembagaan telitiОценок пока нет

- # Transaction Code Transaction DescriptionДокумент6 страниц# Transaction Code Transaction DescriptionVivek Shashikant SonawaneОценок пока нет

- Rubberworld (Phils.), Inc. v. NLRCДокумент2 страницыRubberworld (Phils.), Inc. v. NLRCAnjОценок пока нет

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Free HealthcareДокумент1 страницаAdvantages and Disadvantages of Free HealthcareJames DayritОценок пока нет

- The Role of Black Consciousness in The Experience of Being Black in South-Mphikeleni Mattew MnguniДокумент136 страницThe Role of Black Consciousness in The Experience of Being Black in South-Mphikeleni Mattew MngunimylesОценок пока нет

- Open Book Contract Management GuidanceДокумент56 страницOpen Book Contract Management GuidanceRoberto AlvarezОценок пока нет

- Resort Operations ManagementДокумент15 страницResort Operations Managementasif2022coursesОценок пока нет

- Construction Safety ChetanДокумент13 страницConstruction Safety ChetantuОценок пока нет

- Koalatext 4Документ8 страницKoalatext 4YolandaOrduñaОценок пока нет

- Libanan, Et Al. v. GordonДокумент33 страницыLibanan, Et Al. v. GordonAlvin ComilaОценок пока нет

- Congressional Record - House H104: January 6, 2011Документ1 страницаCongressional Record - House H104: January 6, 2011olboy92Оценок пока нет

- Social Institutions and OrganisationsДокумент1 страницаSocial Institutions and OrganisationsKristof StuvenОценок пока нет

- BHMCT 5TH Semester Industrial TrainingДокумент30 страницBHMCT 5TH Semester Industrial Trainingmahesh kumarОценок пока нет

- Negros Oriental State University Bayawan - Sta. Catalina CampusДокумент6 страницNegros Oriental State University Bayawan - Sta. Catalina CampusKit EdrialОценок пока нет

- Toll BridgesДокумент9 страницToll Bridgesapi-255693024Оценок пока нет

- REINZ Useful Clauses and AuthoritiesДокумент43 страницыREINZ Useful Clauses and AuthoritiesAriel LevinОценок пока нет