Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Temperamental Differences Between Bipolar Disorder, Borderline Personality Disorder, and Attention Deficit/hyperactivity Disorder: Some Implications For Their Diagnostic Validity.

Загружено:

eduardobar2000Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Temperamental Differences Between Bipolar Disorder, Borderline Personality Disorder, and Attention Deficit/hyperactivity Disorder: Some Implications For Their Diagnostic Validity.

Загружено:

eduardobar2000Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

Journal of Affective Disorders ()

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

Q1

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Affective Disorders

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jad

Brief report

Temperamental differences between bipolar disorder, borderline

personality disorder, and attention decit/hyperactivity disorder:

Some implications for their diagnostic validity

Dominique Eich n, Alex Gamma, Tina Malti, Marianne Vogt Wehrli, Michael Liebrenz,

Erich Seifritz, Jiri Modestin

Psychiatric University Hospital, Research Department, Lenggstrasse 31, 8032 Zurich, Switzerland

art ic l e i nf o

a b s t r a c t

Article history:

Received 25 October 2013

Received in revised form

20 May 2014

Accepted 21 May 2014

Background: The relationship between borderline personality disorder (BPD), bipolar disorder (BD), and

attention decit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) requires further elucidation.

Methods: Seventy-four adult psychiatric in- and out-patients, each of them having received one of these

diagnoses on clinical assessment, were interviewed and compared in terms of diagnostic overlap, age

and sex distribution, comorbid substance, anxiety and eating disorders, and affective temperament.

Results: Diagnostic overlap within the three disorders was 54%. Comorbidity patterns and gender ratio

did not differ. The disorders showed very similar levels of cyclothymia.

Limitations: Sample size was small and only a limited number of validators were tested.

Conclusions: The similar extent of cyclothymic temperament suggests mood lability as a common

denominator of BPD, BD, and ADHD.

& 2014 Published by Elsevier B.V.

Keywords:

Borderline

bipolar

ADHD

Diagnostic validity

Temperament

1. Introduction

2. Materials and methods

An important part of establishing diagnostic validity for a disorder

is to delineate it from similar diagnoses in nosological space (Robins

and Guze, 1970), i.e. to establish discriminant validity. This is possible

by comparing the candidate disorders by a number of external

validators such as family history, sex distribution, onset and course,

treatment response, and comorbidity.

Here we are concerned with the discrimination between a triplet

of disorders that are frequently diagnosed and show considerable

empirical overlap: borderline personality disorder (BPD), bipolar

disorder (BD) and attention decit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

This overlap consists of several aspects: rst, these disorders are

frequently co-morbid (Ferrer et al., 2010; Kessler et al., 2006; Perugi

et al., 2013); second, they show a moderate overlap in diagnostic

criteria (Milberger et al., 1995); third, in clinical practice, it is

sometimes difcult to know which of the three disorders a patient's

symptoms belong to (Nilsson et al., 2010; Skirrow et al., 2012). We

report results from a patient study comparing these diagnoses in

terms of diagnostic overlap, sex distribution, comorbidity, and

affective temperaments.

2.1. Patients

n

Correspondence to: Psychiatric University Hospital Zurich, Division of ADHD

research, Lenggstrasse 31, 8032 Zurich, Switzerland. Tel.: 41 443842615

E-mail address: Dominique.Eich@puk.ch (D. Eich).

Consecutive referrals to the Psychiatric University Hospital

(PUK) whose principal clinical ICD-10 diagnoses at admission were

either BD, BPD, or ADHD were recruited for thorough diagnostic

re-evaluation. As the number of adult patients with ADHD referred

for a psychiatric hospitalization is limited, out-patients treated at

the consultation service for ADHD were additionally recruited. Of

104 subjects initially asked for participation, 25 declined. Of the

remaining 79 subjects, 5 did not meet the diagnostic criteria. The

nal sample consisted of 74 patients: 27 with BPD, 24 with BD (17

bipolar-I and 7 bipolar-II), and 23 with ADHD. Before participation

in the study, all subjects received written study information and

gave their written informed consent. The study was approved by

the local ethics committee.

2.2. Psychometric and diagnostic re-evaluation

The levels of ve temperaments (depressive, hyperthymic,

cyclothymic, anxious, and irritable) during the lifespan were

assessed using the TEMPS-A (Akiskal et al., 2002) self-rating scale.

The TEMPS-A asks for a patient's state during most of their life.

DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria for ADHD, which are nearly identical,

are geared towards children. They are limited to symptoms of

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.05.028

0165-0327/& 2014 Published by Elsevier B.V.

Please cite this article as: Eich, D., et al., Temperamental differences between bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, and

attention.... Journal of Affective Disorders (2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.05.028i

D. Eich et al. / Journal of Affective Disorders ()

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity. Additional criteria

allowing for diagnosis of ADHD in adults have been established

by Wender (1995) in the so-called Utah-criteria. They include

additional subscales for affective lability, temperament, emotional

excitability, and disorganization, and are operationalized in the

clinician-administered WenderReimherr Interview (Ro

sler et al.,

2008), which was the diagnostic tool used in the present study.

In addition, the WURS-k (Retz-Junginger et al., 2003) and ADHS-SB

(Ro

sler et al., 2004) self-rating scales, which incorporate both

ICD-10 and DSM-IV criteria, were used for the retrospective

assessment in adulthood of childhood ADHD and the current

assessment of adult ADHD, respectively. BPD, BD and comorbid

substance use, anxiety, and eating disorders were assessed by the

respective sections of SCID-I/II (First et al., 1997, 2002). BD patients

were interviewed during a euthymic state. Both initial and

re-evaluated diagnoses were made by experienced clinicians.

2.3. Statistics

Between-group comparisons of frequencies were carried

out using 2-tests; comparisons on continuous data used Mann

Whitney and KruskalWallis tests. Temperaments were not only

compared among groups dened by their primary diagnoses, but

also among groups of pure cases without diagnostic overlap.

There were 12 pure bipolar, 12 pure borderline, and 10 pure ADHD

patients. Analyses were performed in SPSS 20 (IBM SPSS Statistics

for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.).

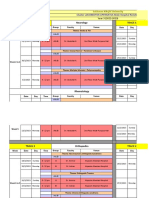

Table 2

Affective temperament.

Primary diagnosis

BPD

BD

ADHD

N

TEMPS-A

Depressive

Cyclothymic

Hyperthymic

Irritable

Anxious

27

Mean (SD)

12.2 (3.6)

13.0 (3.6)

8.5 (4.1)

10.5 (4.3)a

14.9 (4.5)

24

Mean (SD)

9.8 (3.6)

11.9 (4.7)

10.8 (4.8)

7.5 (5.1)

11.3 (5.9)b

23

Mean (SD)

10.9 (4.4)

12.7 (4.9)

10.2 (4.7)

10.0 (4.7)

15.2 (5.1)

.12

.72

.13

.017

.016

Pure diagnosis

BPD

BD

ADHD

N

TEMPS-A

Depressive

Cyclothymic

Hyperthymic

Irritable

Anxious

12

Mean (SD)

12.4 (3.7)c,d

10.7 (3.0)

6.6 (3.7)e

9.1 (3.0)f

14.2 (4.1)g

12

Mean (SD)

8.7 (2.8)

9.7 (4.9)

10.0 (4.7)

5.0 (3.6)

8.6 (5.4)h

10

Mean (SD)

7.7 (3.6)

9.6 (5.0)

10.9 (4.1)

7.9 (3.2)

12.3 (5.1)

.007

.66

.031

.035

.006

BPD Borderline personality disorder, BD Bipolar disorder, ADHD Attention

decit/hyperactivity disorder.

a

p o.02 vs. BD, MannWhitney U test.

p o .02 vs. ADHD, MannWhitney U test.

p o .02 vs. BD, MannWhitney U test.

d

p o .003 vs. ADHD, MannWhitney U test.

e

p o.007 vs. ADHD, MannWhitney U test.

f

p o .02 vs. BD, MannWhitney U test.

g

po .001 vs. BD, MannWhitney U test.

h

p o .05 vs. ADHD, MannWhitney U test.

b

c

3. Results

Sociodemographic data are shown in Table 1. Bipolar patients

were statistically signicantly older than borderline and ADHD

patients. No other differences were found.

For both groups dened by primary and by pure diagnoses,

irritable and anxious temperaments were the lowest in bipolar

patients. Hyperthymic temperament showed a trend towards lower

values in borderline patients in the primary groups, which became

signicant in the pure groups. Similarly, depressive temperament

showed a trend to be the highest in borderline patients in the

primary groups, which became signicant in the pure groups. Results

are summarized in Table 2.

The pattern of comorbidities among the three diagnoses BPD,

BD, and ADHD is shown in Table 3. All in all, 54% (40/74)

of patients were co-morbid with at least one other disorder

within the triplet of target diagnoses. No statistically signicant

differences in comorbidity with substance use, anxiety, or eating

disorders emerged.

4. Discussion

In a mixed sample of 74 in- and out-patients with primary

diagnoses of BPD, BD, and ADHD, there was considerable diagnostic overlap. At least half of the members of each disorder met

Table 1

Sociodemographic data.

Primary diagnosis

BPD

BD

ADHD

N (%)

Women

Age [mean (SD) years]

Living alone

Employed

27

20 (74)

32.8 (8.8)

20 (74)

13 (52)

24

16 (67)

41.8 (12.9)

17 (71)

11 (46)

23

15 (65)

31.3 (10.3)

17 (74)

15 (68)

.76

.01

.96

.35

Table 3

Comorbidity.

Primary diagnosis

BPD

BD

ADHD

N (%)

BPD

BD

ADHD

Botha

Total

27

6 (22)

7 (26)

2 (7)

15 (56)

24

6 (25)

4 (17)

2 (8)

12 (50)

23

7 (30)

8 (35)

2 (9)

13 (57)

Substance use

Anxiety disorders

Eating disorders

20 (74)

25 (93)

12 (44)

12 (50)

21 (87)

8 (33)

12 (52)

20( 87)

8 (35)

.15

.77

.67

BPD Borderline personality disorder, BD Bipolar disorder, ADHD Attention

decit/hyperactivity disorder.

a

Both comorbid diagnoses present: for BPD this means BD and ADHD were

also present; for BD it means that BPD and ADHD were also present; for ADHD it

means both BPD and BD were also present.

criteria for at least one of the other disorders. Consistent with this,

comorbidity rates for substance use, anxiety disorders and eating

disorder were very similar and not statistically signicantly

different among the groups. Levels of affective temperament were

partly similar among groups, with some notable differences: BPD

patients stood out by low levels of hyperthymia and by high

depressiveness, and BD patients stood out by low levels of anxious

and irritable-explosive temperament. These differences were all

statistically signicant in the pure groups. A cyclothymic temperament, however, was expressed on a similar and high level by BP,

BPD, and ADHD.

Due to the limited number of validators, this study could not

demonstrate with certainty that the three disorders are different,

let alone denitely the same. However, the ndings point to areas

of overlap and difference that should be investigated further in

larger studies.

Please cite this article as: Eich, D., et al., Temperamental differences between bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, and

attention.... Journal of Affective Disorders (2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.05.028i

D. Eich et al. / Journal of Affective Disorders ()

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

The most striking commonality is the over 50% diagnostic overlap

between these disorders, accompanied by indistinguishable patterns

of comorbidity. While this nding matches frequent comments in the

literature on the difculty of differentiating among these disorders

(Akiskal et al., 1985a, 1985b, 1995; Akiskal, 1981; Nilsson et al., 2010;

Perugi and Akiskal, 2002; Skirrow et al., 2012), the overlap may seem

unusually strong. For example, Philipsen et al. (2008) found only 16%

comorbidity of BPD with ADHD. On the other hand, a more recent

study (Ferrer et al., 2010) reported a number as high as 38%.

Another commonality is the similar degree of cyclothymia in all

three diagnoses. Cyclothymia in the TEMPS-A is very broadly

dened as a chronic, but short-cycling instability of cognition

(sharp vs. dull), behavior (lively vs. sluggish), mood (euphoric vs.

dysphoric), energy (high vs. low), sociability (outgoing vs. withdrawn), self-condence (overcondent vs. unsure), and sleep (high

vs. low need). As such, this scale is likely to be sensitive to different

or overlapping manifestations of instability as encountered in BD,

BPD, and ADHD. High levels on the scale could therefore be

achieved without necessarily indicating a congruence of item

content among the disorders. This might make the scale rather

unspecic, unless the instability of mentation and behavior itself is

considered as a specic symptom. The concept of mood/emotional

lability might be a candidate for such a specic symptom that is

common to these disorders (MacKinnon and Pies, 2006; Perugi et

al., 2003; Skirrow and Asherson, 2012; Skirrow et al., 2009, but see

Benazzi (2008)), but plays itself out over somewhat different time

scales in ADHD, BPD, and BD. Mood lability, however, was not

examined in the present study.

Given the clinical knowledge that BPD and ADHD features are

chronic, interpretation of the temperament results for BD (e.g. lower

ratings for irritability and anxiousness) is difcult because lower

levels of these temperaments in BD could mean two things: BD

patients have a given temperament, but to a lesser extent than BPD

and ADHD; or, BD patients have a given temperament to the same

extent, but less often. Since the TEMPS-A asks for a patient's state

during most of their life, it is possible that bipolar respondents

form a temporal average of their temperament levels, resulting in a

lower value compared to the other, trait-like disorders.

This possibility may, for example, apply to the nding of a

tendency towards higher levels of depressiveness in BPD. BD

patients may episodically be as depressed as BPD patients, but

when evaluating most of their lives, they might rate their level of

depression lower than BPD patients. On the other hand, it is

possible that the intense dysphoria and chronic feelings of emptiness characteristic of BPD affect the depressive dimension of the

TEMPS-A more strongly than even the episodic depressiveness of

bipolar patients. They may also lead to a mitigating effect on

hyperthymia levels. This interpretation is consistent with previous

reports of weaker depressive temperament in BD compared to BPD

(Nilsson et al., 2010) and compared to patient controls (Kesebir et

al., 2005), as well as with a study in young adults showing a lack of

correlation of depressive temperament with either DSM- or broad

bipolar disorder, but a positive correlation with borderline symptoms (Walsh et al., 2012).

Irritable and anxious temperaments were stronger in the BPD

and ADHD groups compared to bipolar patients. This matches the

results found by Nilsson et al. (2010) for female BPD vs. BD

patients. While temporal averaging in BD patients could again be

an explanation, the strong association of irritability with borderline symptoms has been noted before (Walsh et al., 2012),

especially among patients with pronounced cyclothymia (Akiskal

et al., 1979). They display a tendency to overreact to aversive

stimuli with negative affect and to rapid shifts in mood with

erratic behaviors (Walsh et al., 2012).

Regarding high levels of anxious temperament in BPD and ADHD,

indirect support comes from ndings of high harm avoidance in

borderline (Barnow et al., 2006) and ADHD patients (Anckarster

et al., 2006; Mller et al., 2010; Salgado et al., 2009), since harm

avoidance refers to a general propensity for being pessimistic and

anxious. In both adult BPD (Ferrer et al., 2010; Philipsen et al., 2008)

and ADHD (Nigg et al., 2002; Skirrow and Asherson, 2012), high

comorbidity rates with anxiety symptoms and disorders have been

reported. However, the effect of having both disorders is not clear

yet. While in BPD women specic phobias and panic disorder were

related to comorbid ADHD (Philipsen et al., 2008); Ferrer et al. (2010)

reported less comorbidity with anxiety disorders in male and female

BPD patients with concomitant ADHD than those without ADHD

(Ferrer et al., 2010).

It is possible that the weaker anxious temperament in our BD

patients is due to their being mostly of the BP-I type. In BP-II

disorder, comorbid anxiety and panic disorders seem to be the rule

(Perugi et al., 2006; Perugi and Akiskal, 2002) and anxious

temperament is more frequent than in BP-I disorder (Fletcher

et al., 2012), in which it has been found not to differ from patientand relative-controls (Kesebir et al., 2005).

This study has signicant limitations. The sample size was

small. Only a limited number of diagnostic validators were used,

while many classical validators such as family history, age of onset,

course, treatment, consequences and outcomes were not available.

Participants were self-selected and may not be representative of

patients with these disorders in general. There is a possibility that

spurious diagnostic overlap could have been generated by inaccurate clinical assessment. We believe this to be unlikely since

our patients have been diagnosed twice (initial and re-evaluated

diagnosis) according to standardized criteria, and due attention

was paid to the fundamental differences of these disorders, such as

the episodic vs. chronic nature of BD and BPD/ADHD, respectively.

However, when comparing episodic with chronic disorders as in

the present study, psychometric ndings are ambiguous between

two alternative interpretations, one of which assumes temporal

averaging of rating levels over episodes, while the other assumes

that rating levels of one or several maximally severe episodes are

reported. Disambiguating between these possibilities requires

further studies addressed to this particular aspect of psychometric

evaluation.

In conclusion, weaker anxious and irritable temperament in BD

and stronger depressive and weaker hyperthymic temperament in

BPD separated the three diagnoses BPD, BD, and ADHD. These

temperamental differences were accentuated in the pure groups,

which might suggest the presence of distinct core disorders; thus

adding discriminant validity to the diagnostic separation of the

three disorders. This issue should be further investigated in more

highly powered studies. However, in the primary groups there was

considerable diagnostic overlap, indistinguishable comorbidity

rates for substance use, anxiety and eating disorders, and very

similar levels of cyclothymia, which may point to mood lability as

a common denominator of these disorders (Perugi et al., 2012).

Clinicians should be aware of the frequent co-occurrence of these

conditions and, when one of them is present, routinely check for

the presence of the other two.

Role of funding source

This study required no sponsoring or external funding, with the exception of

ML, who was nancially supported by the Prof. Dr. Max Clotta foundation, Zurich,

Switzerland, and the Uniscientia foundation, Vaduz, Principality of Liechtenstein.

These foundations played no role in any part of this study, viz. neither in the study

design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the

report, and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Conict of interest

DE, AG, TM, MVW, ML, ES, and JM declare that they have no conicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Eich, D., et al., Temperamental differences between bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, and

attention.... Journal of Affective Disorders (2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.05.028i

D. Eich et al. / Journal of Affective Disorders ()

1

Acknowledgments

Michael Liebrenz was nancially supported by the Prof. Dr. Max Clotta

2 Q2

foundation, Zurich, Switzerland, and the Uniscientia foundation, Vaduz, Principality

3

of Liechtenstein.

4

5

References

6

7

Akiskal, H.S., Brieger, P., Mundt, C., Angst, J., Marneros, A., 2002. Temperament und

8

affektive Sto

rungen. Der Nervenarzt 73, 262271.

9

Akiskal, H.S., Chen, S.E., Davis, G.C., Puzantian, V.R., Kasper, J., Bolinger, J.M., 1985a.

Borderline: an adjective in search of a noun. J. Clin. Psychiatr..

10 Q3

Akiskal, H.S., Khani, M.K., Scott-Strauss, A., 1979. Cyclothymic temperamental

11

disorders. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2, 527557.

12

Akiskal, H.S., Yerevanian, B.I., Davis, G.C., King, D., Lemmi, H., 1985b. The nosologic

status of borderline personalityclinical and polysomnographic study. Am. J.

13

Psychiatr. 142, 192198.

14

Akiskal, H.S.H., 1981. Subaffective disorders: dysthymic, cyclothymic and bipolar II

15

disorders in the borderline realm. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 4, 2546.

Akiskal, H.S.H., Maser, J.D.J., Zeller, P.J.P., Endicott, J.J., Coryell, W.W., Keller, M.M.,

16

Warshaw, M.M., Clayton, P.P., Goodwin, F.F., 1995. Switching from unipolar to

17

bipolar II. An 11-year prospective study of clinical and temperamental pre18

dictors in 559 patients. Arch. Gen. Psychiatr. 52, 114123.

19

Anckarster, H., Stahlberg, O., Larson, T., Hakansson, C., Jutblad, S.-B., Niklasson, L.,

Nydn, A., Wentz, E., Westergren, S., Cloninger, C., Gillberg, C., Rastam, M.,

20

2006. The impact of ADHD and autism spectrum disorders on temperament,

21

character, and personality development. Am. J. Psychiatr. 163, 12391244.

22

Barnow, S., Herpertz, S.C., Spitzer, C., Stopsack, M., Preuss, U.W., Grabe, H.J., Kessler,

C., Freyberger, H.J., 2006. Temperament and character in patients with border23

line personality disorder taking gender and comorbidity into account. PsychoQ4

24

pathology 40, 369378.

25

Benazzi, F., 2008. A relationship between bipolar II disorder and borderline personality disorder? Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatr. 32, 10221029.

26

Ferrer, M., Andin, O., Matal, J., Valero, S., Navarro, J.A., Ramos-Quiroga, J.A.,

27

Torrubia, R., Casas, M., 2010. Comorbid attention-decit/hyperactivity disorder

28

in borderline patients denes an impulsive subtype of borderline personality

disorder. J. Personal. Disord. 24, 812822.

29

First, M.B., Gibbon, M., Williams, J.B.W., Spitzer, R.L., Benjamin, L.S., 1997. Structured

30

Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II). American

31

Psychiatric Press, Inc., Washington, D.C..

First, M.B., Spitzer, R.L., Gibbon, M., Williams, J.B.W., 2002. Structured Clinical

32

Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-Patient

33

Edition (SCID-I/NP). Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute,

34

New York.

35

Fletcher, K., Parker, G., Barrett, M., Synnott, H., McCraw, S., 2012. Temperament and

personality in bipolar II disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 136, 304309.

36

Kesebir, S., Vahip, S., Akdeniz, F., Ync, Z., Alkan, M., Akiskal, H., 2005. Affective

37

temperaments as measured by TEMPS-A in patients with bipolar I disorder and

38

their rst-degree relatives: a controlled study. J. Affect. Disord. 85, 127133.

Kessler, R.C.R., Adler, L.L., Barkley, R.R., Biederman, J., Conners, C.K.C., Demler, O.O.,

39

Faraone, S.V., Greenhill, L.L.L., Howes, M.J.M., Secnik, K.K., Spencer, T.T., Ustun, T.B.T.,

40

Walters, E.E.E., Zaslavsky, A.M.A., 2006. The prevalence and correlates of adult

41

ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey

Replication. Am. J. Psychiatr. 163, 716723.

42

MacKinnon, D.F., Pies, R., 2006. Affective instability as rapid cycling: theoretical and

43

clinical implications for borderline personality and bipolar spectrum disorders.

44

Bipolar Disord. 8, 114.

Milberger, S., Biederman, J., Faraone, S.V., Murphy, J., Tsuang, M.T., 1995. Attention45

decit hyperactivity disorder and comorbid disordersissues of overlapping

46

symptoms. Am. J. Psychiatr. 152, 17931799.

47

48

Mller, D.J.D., Chiesa, A.A., Mandelli, L.L., De Luca, V.V., De Ronchi, D.D., Jain, U.U.,

Serretti, A.A., Kennedy, J.L.J., 2010. Correlation of a set of gene variants, life

events and personality features on adult ADHD severity. J. Psychiatr. Res. Q5

44598604

Nigg, J.T., John, O.P., Blaskey, L.G., Huang-Pollock, C.L., Willcutt, E.G., Hinshaw, S.P.,

Pennington, B., 2002. Big ve dimensions and ADHD symptoms: links between

personality traits and clinical symptoms. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 83, 451469.

Nilsson, A.K.K., Jrgensen, C.R., Straarup, K.N., Licht, R.W., 2010. Severity of affective

temperament and maladaptive self-schemas differentiate borderline patients,

bipolar patients, and controls. Compr. Psychiatr. 51, 486491.

Perugi, G., Angst, J., Azorin, J.-M., Bowden, C., Vieta, E., Young, A.H., The BRIDGE

Study Group, 2013. The bipolar-borderline personality disorders connection in

Q6

major depressive patients. Acta Psychiatr. Scand.128376383

Perugi, G., Toni, C., Maremmani, I., Tusini, G., Ramacciotti, S., Madia, A., Fornaro, M.,

Akiskal, H.S., 2012. The inuence of affective temperaments and psychopathological traits on the denition of bipolar disorder subtypes: a study on bipolar I

Italian national sample. J. Affect. Disord. 136, e41e49.

Perugi, G., Toni, C., Passino, M.C.S., Akiskal, K.K., Kaprinis, S., Akiskal, H.S., 2006.

Bulimia nervosa in atypical depression: the mediating role of cyclothymic

temperament. J. Affect. Disord. 929197

Perugi, G., Toni, C., Travierso, M.C., Akiskal, H.S., 2003. The role of cyclothymia in

atypical depression: toward a data-based reconceptualization of the

borderline-bipolar II connection. J. Affect. Disord. 73, 8798.

Perugi, G.G., Akiskal, H.S., 2002. The soft bipolar spectrum redened: focus on the

cyclothymic, anxious-sensitive, impulse-dyscontrol, and binge-eating connection in bipolar II and related conditions. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 25, 713737.

Philipsen, A., Limberger, M.F., Lieb, K., Feige, B., Kleindienst, N., Ebner-Priemer, U.,

Barth, J., Schmahl, C., Bohus, M., 2008. Attention-decit hyperactivity disorder

as a potentially aggravating factor in borderline personality disorder. Br. J.

Psychiatr. 192, 118123.

Retz-Junginger, P., Retz, W., Blocher, D., Stieglitz, R.-D., Georg, T., Supprian, T.,

Wender, P.H., Ro

sler, M., 2003. Reliability and validity of the German short

version of the WenderUtah rating scale for the retrospective assessment of

attention decit/hyperactivity disorder. Nervenarzt 74, 987993.

Robins, E., Guze, S.B., 1970. Establishment of diagnostic validity in psychiatric

illness: its application to schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatr. 126, 983987.

Ro

sler, M., Retz, W., Retz-Junginger, P., Thome, J., Supprian, T., Nissen, T., Stieglitz,

R.-D., Blocher, D., Hengesch, G., Trott, G.E., 2004. Tools for the diagnosis of

attention-decit/hyperactivity disorder in adults. Self-rating behaviour questionnaire and diagnostic checklist. Nervenarzt 75, 888895.

Ro

sler, M., Retz-Junginger, P., Retz, W., Stieglitz, R.-D., 2008. HASEHomburgerADHS-Skalen fr Erwachsene. Hogrefe, Go

ttingen.

Salgado, C.A.I., Bau, C.H.D., Grevet, E.H., Fischer, A.G., Victor, M.M., Kalil, K.L.S.,

Sousa, N.O., Garcia, C.R., Belmonte-de-Abreu, P., 2009. Inattention and hyperactivity dimensions of ADHD are associated with different personality proles.

Psychopathology 42, 108112.

Skirrow, C., Asherson, P., 2012. Emotional lability, comorbidity and impairment in Q7

adults with attention-decit hyperactivity disorder. J. Affect. Disord., 18.

Skirrow, C., Hosang, G.M., Farmer, A.E., Asherson, P., 2012. An update on the

debated association between ADHD and bipolar disorder across the lifespan. J.

Affect. Disord. 141, 143159.

Skirrow, C., McLoughlin, G., Kuntsi, J., Asherson, P., 2009. Behavioral, neurocognitive

and treatment overlap between attention-decit/hyperactivity disorder and

mood instability. Expert Rev. Neurother. 9, 489503.

Walsh, M.A., Royal, A.M., Barrantes-Vidal, N., Kwapil, T.R., 2012. The association of

affective temperaments with impairment and psychopathology in a young

adult sample. J. Affect. Disord. 141, 373381.

Wender, P.H., 1995. Attention-decit hyperactivity disorder in adults. University

Press, Oxford.

Please cite this article as: Eich, D., et al., Temperamental differences between bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, and

attention.... Journal of Affective Disorders (2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.05.028i

Вам также может понравиться

- Bruch 1958 PDFДокумент6 страницBruch 1958 PDFeduardobar2000Оценок пока нет

- Borderline - An Adjective in Search of A NoumДокумент8 страницBorderline - An Adjective in Search of A Noumeduardobar2000Оценок пока нет

- Moskowitz.2004 Catatonia - Evolutionary PDFДокумент19 страницMoskowitz.2004 Catatonia - Evolutionary PDFeduardobar2000Оценок пока нет

- Obesity, The Jews and Psychoanalisis (Sander L. Gilman, 2006)Документ13 страницObesity, The Jews and Psychoanalisis (Sander L. Gilman, 2006)eduardobar2000Оценок пока нет

- Effect of Combined Naltrexone and Bupropion Therapy On The Brain's Reactivity To Food CuesДокумент7 страницEffect of Combined Naltrexone and Bupropion Therapy On The Brain's Reactivity To Food Cueseduardobar2000Оценок пока нет

- Developmental Obesity and SchizophreniaДокумент6 страницDevelopmental Obesity and Schizophreniaeduardobar2000100% (1)

- Moving Towards Causality in Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Overview of Neural and Genetic MechanismsДокумент13 страницMoving Towards Causality in Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Overview of Neural and Genetic Mechanismseduardobar2000100% (1)

- Aspectos Psicologicos de La ObesidadДокумент14 страницAspectos Psicologicos de La ObesidadNicolás CanalesОценок пока нет

- Child Murder by Parents and Evolutionary PsychologyДокумент15 страницChild Murder by Parents and Evolutionary Psychologyeduardobar2000Оценок пока нет

- Aspectos Psicologicos de La ObesidadДокумент14 страницAspectos Psicologicos de La ObesidadNicolás CanalesОценок пока нет

- Schizophrenia and Suicide: Systematic Review of Risk FactorsДокумент13 страницSchizophrenia and Suicide: Systematic Review of Risk Factorseduardobar2000Оценок пока нет

- The Association of Restrained Eating With Weight Change Over Time in A Community-Based Sample of TwinsДокумент13 страницThe Association of Restrained Eating With Weight Change Over Time in A Community-Based Sample of Twinseduardobar2000Оценок пока нет

- The Relationship Between Dissociation and Voices: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-AnalysisДокумент52 страницыThe Relationship Between Dissociation and Voices: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysiseduardobar2000100% (1)

- BMJ f185 Full PDFДокумент13 страницBMJ f185 Full PDFeduardobar2000Оценок пока нет

- Kretschmer. Heredity and Constitution.Документ4 страницыKretschmer. Heredity and Constitution.eduardobar2000Оценок пока нет

- "Scared Stiff": Catatonia As An Evolutionary-Based Fear ResponseДокумент19 страниц"Scared Stiff": Catatonia As An Evolutionary-Based Fear Responseeduardobar2000Оценок пока нет

- Homology, Homoplasy, Novelty, and BehaviorДокумент9 страницHomology, Homoplasy, Novelty, and Behavioreduardobar2000Оценок пока нет

- (CANMAT) GuideliCanadian Network For Mood and Anxiety Treatmentsnes For The Management of Patients WithbipolarДокумент65 страниц(CANMAT) GuideliCanadian Network For Mood and Anxiety Treatmentsnes For The Management of Patients WithbipolarDahij1014Оценок пока нет

- Towards A Bottom-Up Perspective On Animal and Human CognitionДокумент8 страницTowards A Bottom-Up Perspective On Animal and Human Cognitioneduardobar2000Оценок пока нет

- Systems Genetics of Obesity in An F2 Pig Model by Genome-Wide Association, Genetic Network, and Pathway AnalysesДокумент15 страницSystems Genetics of Obesity in An F2 Pig Model by Genome-Wide Association, Genetic Network, and Pathway Analyseseduardobar2000Оценок пока нет

- Animal Models of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Exploring Pharmacology and Neural SubstratesДокумент17 страницAnimal Models of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Exploring Pharmacology and Neural Substrateseduardobar2000Оценок пока нет

- Changes in Body Composition Over 8 Years in A Randomized Trial of A Lifestyle Intervention: The Look AHEAD StudyДокумент8 страницChanges in Body Composition Over 8 Years in A Randomized Trial of A Lifestyle Intervention: The Look AHEAD Studyeduardobar2000Оценок пока нет

- Constraints and Flexibility in Mammalian Social Behaviour: Introduction and SynthesisДокумент10 страницConstraints and Flexibility in Mammalian Social Behaviour: Introduction and Synthesiseduardobar2000Оценок пока нет

- Psychobiological Traits in The Risk Profile For Overeating and Weight GainДокумент5 страницPsychobiological Traits in The Risk Profile For Overeating and Weight Gaineduardobar2000Оценок пока нет

- The Hunger Genes: Pathways to Obesity and Individual SusceptibilityДокумент14 страницThe Hunger Genes: Pathways to Obesity and Individual Susceptibilityeduardobar2000Оценок пока нет

- The Nocturnal Bottleneck and The Evolution of Activity Patterns in MammalsДокумент11 страницThe Nocturnal Bottleneck and The Evolution of Activity Patterns in Mammalseduardobar2000Оценок пока нет

- The Thrifty Psychiatric PhenotypeДокумент3 страницыThe Thrifty Psychiatric Phenotypeeduardobar2000Оценок пока нет

- Neural Control of Energy Balance: Translating Circuits To TherapiesДокумент13 страницNeural Control of Energy Balance: Translating Circuits To Therapieseduardobar2000Оценок пока нет

- Nutrition: Applied Nutritional InvestigationДокумент6 страницNutrition: Applied Nutritional Investigationeduardobar2000Оценок пока нет

- Obese-Type Gut Microbiota Induce Neurobehavioral Changes in The Absence of ObesityДокумент9 страницObese-Type Gut Microbiota Induce Neurobehavioral Changes in The Absence of Obesityeduardobar2000Оценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Nervous System and Endocrine SystemДокумент90 страницNervous System and Endocrine SystemCeres LucenteОценок пока нет

- Neuro Motor Readiness Pl2011Документ94 страницыNeuro Motor Readiness Pl2011mohitnet1327100% (3)

- Kessler 2005Документ11 страницKessler 2005mccg1478Оценок пока нет

- Psychedelic IntegrationДокумент91 страницаPsychedelic IntegrationWhomever me100% (3)

- Axonal degeneration: causes, effects and regenerationДокумент1 страницаAxonal degeneration: causes, effects and regenerationYogi drОценок пока нет

- Pinocchio SyndromeДокумент1 страницаPinocchio SyndromeTakeshi ClairОценок пока нет

- Five Senses Lesson PlanДокумент6 страницFive Senses Lesson PlanJolie rose CapanОценок пока нет

- Ana Phisio Lab Report.Документ4 страницыAna Phisio Lab Report.Diana Amor100% (1)

- What Is The Nervous SystemДокумент3 страницыWhat Is The Nervous SystemSittie Asleah SandiganОценок пока нет

- Principles of Hearing Aid AudiologyДокумент9 страницPrinciples of Hearing Aid AudiologyANURAG PANDEYОценок пока нет

- SMK MAMBAU SCIENCE CURRICULUM SPECIFICATIONSДокумент26 страницSMK MAMBAU SCIENCE CURRICULUM SPECIFICATIONSNurul AzniОценок пока нет

- Perceptual Pleasure and The Brain by Irving Biederman & Edward VesselДокумент8 страницPerceptual Pleasure and The Brain by Irving Biederman & Edward VesselAmiraОценок пока нет

- Otvori Glave PDFДокумент1 страницаOtvori Glave PDFAnnieОценок пока нет

- Brainstem Bravo AnnotatedДокумент13 страницBrainstem Bravo AnnotatedMia CadizОценок пока нет

- Febrile SeizureДокумент6 страницFebrile SeizurepipimseptianaОценок пока нет

- The Rare and The Unexpected Miller Fisher SyndromeДокумент4 страницыThe Rare and The Unexpected Miller Fisher SyndromedoctorebrahimОценок пока нет

- Trace Decay Theory of ForgettingДокумент3 страницыTrace Decay Theory of ForgettingJecel Biagan100% (2)

- Perception Chapter 2Документ37 страницPerception Chapter 2Hajra ArifОценок пока нет

- Abnormal Psychology 7th Edition by Susan Nolen Hoeksema-Test BankДокумент60 страницAbnormal Psychology 7th Edition by Susan Nolen Hoeksema-Test BankakasagillОценок пока нет

- Neurologic NCLEX Practice Test Part 1Документ10 страницNeurologic NCLEX Practice Test Part 1mpasague100% (2)

- Lesions of Upper Motor Neurons and Lower Motor NeuronsДокумент9 страницLesions of Upper Motor Neurons and Lower Motor NeuronsAdhitya Rama Jr.Оценок пока нет

- Responses in Animals-OCR Biology A2Документ17 страницResponses in Animals-OCR Biology A2Alan TaylorОценок пока нет

- ILAE classification of seizures and epilepsyДокумент13 страницILAE classification of seizures and epilepsyKrissia SalvadorОценок пока нет

- Understanding Kundalini Energy and its Role in Spiritual EvolutionДокумент190 страницUnderstanding Kundalini Energy and its Role in Spiritual Evolutionnityanandroy100% (1)

- Sulaiman AlRajhi University Neurology & Orthopedics Hospital Rotation ScheduleДокумент10 страницSulaiman AlRajhi University Neurology & Orthopedics Hospital Rotation ScheduleAbdullah MelhimОценок пока нет

- Neuroplasticity: Presented By: Advincula, Arnina Fortus, Jacyrone Pitpit, MarcusДокумент17 страницNeuroplasticity: Presented By: Advincula, Arnina Fortus, Jacyrone Pitpit, MarcusCLAIRE DENISSE DEVISОценок пока нет

- Surgical Treatment of Traumatic Bifrontal Contusion When and HowДокумент37 страницSurgical Treatment of Traumatic Bifrontal Contusion When and HowNGUYỄN HOÀNG LINHОценок пока нет

- Brain Booster WorkbookДокумент10 страницBrain Booster WorkbookPete Singh50% (2)

- Brain Parts and Functions Chart KeyДокумент2 страницыBrain Parts and Functions Chart Keybhihi jkgug;u75% (4)

- WBBSE Class IX English SyllabusДокумент47 страницWBBSE Class IX English SyllabusSoumadip MukherjeeОценок пока нет