Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

The Byzantine Tribunals: Problems in The Application of Justice and State Policy (9th-12th C.)

Загружено:

Ivanovici DanielaОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The Byzantine Tribunals: Problems in The Application of Justice and State Policy (9th-12th C.)

Загружено:

Ivanovici DanielaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Helen Saradi

The Byzantine Tribunals: Problems in the Application of Justice

and State Policy (9th-12th c.)

In: Revue des tudes byzantines, tome 53, 1995. pp. 165-204.

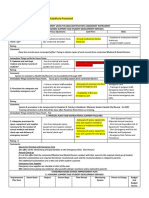

Abstract

REB 53 1995 France p. 165-204

Helen Saradi, The Byzantine Tribunals : Problems in the Application of Justice and State Policy (9th-12th c). In the Byzantine

sources judicial corruption is clearly distinguished from the judges' right to bend the law and adapt it to each particular case

according to the principle of oikonornia, recognized already by the imperial legislation. According to Justinian's Novels judicial

corruption was the result of the judges' insuffi cient training. Justinian treated the problem as an administrative one, since the

functionaries were also assuming judicial responsibilities. A definition of judicial corruption in social terms is found only in the

Ecloga of Leo III the Isaurian : bribery ; favour to friends ; protection from hostile acts ; fear of the dynatoi. But the legislator

placed the problem at the level of Christian morality. Later Leo VI tried to secure the good function of the Byzantine judicial

system by imposing temporal and even spiritual punishment. The measures of the emperors of the following centuries were

inspired either by Justinian's approach or by that of Leo III. In the Novels of the emperors of the Macedonian dynasty on the

preemption right of the poor, judicial corruption is denounced again as a cause of social injustice. Finally, Constantine

Monomachos tried to create an incorruptible judicial system by offering the judges high education with the establishment of the

school of Law. Influence of the Justinianic Novels has been discerned in this approach.

Citer ce document / Cite this document :

Saradi Helen. The Byzantine Tribunals: Problems in the Application of Justice and State Policy (9th-12th c.). In: Revue des

tudes byzantines, tome 53, 1995. pp. 165-204.

doi : 10.3406/rebyz.1995.1904

http://www.persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/rebyz_0766-5598_1995_num_53_1_1904

THE BYZANTINE TRIBUNALS:

PROBLEMS IN THE APPLICATION

OF JUSTICE AND STATE POLICY

(9th- 12th c.)

Helen SARADI

(Basil. 2, 1, 10; Syn. Bas. , 32, 1).

The purpose of this paper is to draw attention to some of the problems of

the Byzantine judicial system regarding the application of justice, the views

of the Byzantines about these problems, and the solutions with which the

State tried to solve them. The subject is complex and it is intimately related

to the structure of the administrative machine of the empire, the concept of

the office of the judges and their legal training. The various approaches of the

State to the problems of the Byzantine judiciary which we will discern from

the 9th to the 12th c. will be evaluated in the context of the historical tradi

tionof the Byzantine judicial system.

I. The earlier tradition

It is known that in Byzantium judicial power was not separated from the

state administration. A slow development of the judicial system in the early

Byzantine period determined the future form of the Byzantine courts and the

nature of the office of the judge. The most remarkable change was that the

provincial governors and their judges were gradually assuming the judicial

power which was originally in the hands of the municipal magistrates. Accor

dingto an ancient Roman tradition the magistrates were granted judicial

power in cases of their administrative competence as well as in cases of a

disciplinary nature over their subordinates. From the 4th c. the tendency has

been discerned for administrative functionaries to successfully compete with

Revue des tudes Byzantines 53, 1995, p. 165-204.

166

HELEN SARADI

the ordinary courts and to handle an increasingly greater number of cases1.

Thus since the judicial system was not based on professionals independent

from the civil and military administration, most of the judges did not possess

legal training. On the other hand, since justice was part of the duties of the

high officers, in particular the provincial governors, men with knowledge of

law were usually hired for such positions2. In order to secure acceptable

standards of justice, the office of the assessor was introduced early on in

various administrative offices. The assessors were judicial advisors. They

were also called .

The Justinianic legislation illustrates in a unique way the problems of the

early Byzantine judicial system and of the emperor's approach to them. The

new measures introduced by the Novel 82 on the judges (

' ), issued in the year 539, are justified by the confu

sionwhich existed in the judicial profession, and the emperor's intention was

to establish an order in this matter. The first issue that is raised is the legal

training of the judges. In the future, no one can be promoted to the office of

judge without knowledge of laws ( ) or some practical expe

rience in legal matters ( : pr.). Of course asses

sors were traditionally assigned by the magistrates to handle the legal ques

tions and replace the magistrates in their judicial duties when the latter were

busy with other administrative business3. But the assessors did not hold an

office () nor did they belong to the imperial administration (

). The legislator declares that it was not appropriate that the

judges transfer judicial matters to others (the assessors) and he intends to

correct this situation for the benefit of the citizens. Therefore he offers the

office of the high judge to men of the bar () and to other high officers

who already had significant experience in public administration and in legal

matters {cap. I). Magistrates could bring their lawsuits before these high jud

ges or delegate to their assessors only parts of the cases for examination,

while the magistrates themselves would be responsible for the final decision

{cap. II). The judges were also to be responsible for the integrity of their

assistants; if the latter were suspected of corruption, they should be replaced

{cap. VII). The cap. IX regulates the salary of the judges drawn on the

imperial treasury, as well as the payment of the litigants. The cap. XI of the

same Novel stipulates on appeals: some citizens promised with a solemn oath

that they would respect the decision of the judge they had chosen for their

case. The legislator admits that a judge could be entirely incompetent in both

1. Cf. A. H. M. Jonfs, The Later Roman Empire. 284-602, Oxford 1964, p. 484 ff.;

Idem, Studies in Roman Government and Law, Oxford 1960, p. 59-63; M. Kasfr, Das

rmische Zivilprozessrecht, Munich 1966, p. 434 ff.

2. Cf. the examples in: Jones, The Later Roman Empire, n. 97.

3. Prooimion'.

,

'

. Cf. CTh 1, 34, 1 and 2 (de adsessoribus, domesticis et cancellariis); CJ 1, 51 (de

adsessoribus et domesticis et cancellariis judicum); 27, 2, 22, 25, 28, 31, 34 {a. 534);

Nov. 24, 6; 25, 1 and 6; 26, 5; 27, 2; 28, 3; 29, 2 (; a. 535); 30, 6 {a. 536); 31 ,

1; 102, 2.

THE BYZANTINE TRIBUNALS (9th- 12th C.)

167

training and experience, in which case the litigants had the right to appeal to

another tribunal, but they would pay a penalty for perjury. In this Novel the

ignorance of the judges is particularly stressed ( (pr.),

...

(cap. XI and 1). It is important to note that the Novel 82 is included in the

Basilica 7, 1, 4-13.

The assessors, legal experts {juris studiosi) known already in classical

Roman law, were gradually institutionalized in the bureaucratic system from

the 4th c. onwards4. By the time of Justinian they had become important

officers of the imperial administration. In the C.J 1,5, 1 they are placed

before the other officers of the judges (de assessoribus et domesticis et cancellariis judicium). Their training in law and rhetoric made them indispensable as

legal advisers of the judges5. In the Novel 60, cap. II it is stipulated that the

assessors should not hear any case without the arehons being present, but it is

the latter who should hear the depositions of the litigants and pronounce the

judgement6. From the same text we learn that the assessors were either

lawyers or other professionals or even state officers (cap. II, 1). At the time of

Justinian John Lydus (De magistratibus III, 11) offers a description of the

judicial procedure at the court of the Prefect: after the assessment was made

( ) the decision was produced ( ), the assessors (

)7 who wrere men very learned in law ( ), read the decision and gave the document to the Prefect to sign it

( )8.

In these early centuries, the most serious problem of the judicial system

was the corruption of the judges. This is attested in various sources: legisla

tive,historiographical and literary9. In theory of course the judges were

expected to be impartial, disinterested and to apply the law. There were,

however, several constitutions which recognized a certain degree of freedom

in the interpretation of the law by the judges. This principle is expressed in a

4. On the Roman assessors cf. . Behrends. Der Assessor zur Zeit der klassischen

Rechtswissenschaft, ZSSHFt 99, 1969, p. 192-226.

5. Ibidem, p. 226; Kser, op. cit., p. 404 ff.

6. Cf. V. Zii.LETTi, Stadi sut processo civile giuslinianeo, Milan 1965, p. 195 ff.;

D. Simon, Untersuchungen zum justinianischen Zivilprozess, Munich 1969, p. 13.

7. In other sources the assessor is called : Behrends, Assessor,

op. cil., p. 221 n. 154.

8. Ioannis Lydi de Magistratibus populi romani libri 1res, ed. R. Wuensch, Stuttgart

1967, p. 97-98 (= A.C. Bandy, Joannes Lydus, On Powers or the Magistracies of the

Roman State, Philadelphia 1983, p. 148-150). On this text and on the Justinianic reform

of the Prefecture cf. R.D. Scott, John Lydus on Some Procedural Changes,

4, 1972, p. 441-451.

9. On various forms of corruption in Antiquity cf. W. Schuller (ed.), Korruption

im Altertum, Munich, Vienna 1982. On judicial corruption according to the ecclesiasti

cal

sources cf. Von Ignazio Prez de Heredia y Valle, Die Sorge um die Unparteil

ichkeitdes Richters im Allgemeinen in der Lehre der Synoden und der Vter vom iv.

Jahrhundert his zum Ende der Vterzeit. Archiv fr Kathotische Kirchenrecht 1 48. 1979.

i). 380-408.

168

HELEN SARADI

constitution of Septimius Severus of the year 224 which has been included in

the Justinianic Code 9, 8, 1: "You are not only not permitted to accuse a

judge of the crime of treason, because you allege that he has rendered a

decision against Our Constitution, but I do not wish accusations of this crime

to be made during My reign on any other grounds whatever" 10. Thus judicial

decisions against the imperial constitutions would not incur capital punish

ment. Practical considerations may have dictated this regulation, such as

allowing the judges a certain degree of freedom in making their decisions in

the context of each case. The text, however, does not mention any such

concern. Similar is the spirit of a Justinianic law of the year 527 (?):

(CJ 3, 1, 11). A constitution of the emperors Constantine and Licinius of the year 314 is even more explicit and as it appears, it introduced a

new principle in the application of justice: that justice or aequilas is more

important than the letter of the law: "It has been decided that, in all things,

the principles of justice and equity, rather than the strict rules of law, should

be observed" {CJ 3, 1, 8).

Underlying this interpretation, we may discern the principle of

11, the origin of which can be traced back to the ancient Greek

tradition as well as to Christian literature; if applied, it could lead the judges

to pronounce decisions ' by adjusting the laws to each particular

case. The CJ 3, 1, 8 is included in the Basilica 7, 6, 8:

. The Basilica 2, 1, 28 reproduce the Dig. 1,

3, 18 that . Thus the application of the

principle of aequitas or in judicial practice was strongly recommend

ed

by the legislators and certainly it was not considered as opening the way

to judgements distorted by the personal motivations of the judges. In prac

tice of course it could be used to serve the judges' personal interests.

It is particularly the Justinianic legislation that dealt with judicial corrupt

ion.Justinian looked at the problem from two angles: a) as resulting from

the lack of legal training of the judges, and thus in his Novel 82 of the year

539, as we have seen, he appointed to the high offices of judges men with legal

training; b) as an administrative problem which he tried to solve with admin

istrative

measures. He believed that the root of the problem was to be found

in the system of suffragium, which was originally an appointment on the basis

of the recommendation of an influential man, and developed into the tradi

tionof selling offices. By the 6th c. in most instances, the money paid for the

suffragium was cashed by the imperial treasury. In the year 535 Justinian

issued the Novel 8 with which he imposed an oath on the provincial governors

denouncing the suffragium. By abolishing the venality of offices the emperor

hoped he would cleanse the administration and he particularly refers to jus10. Transi. S. P. Scott (Etiam ex aliis causis inaiestatis crimina cessant meo saeculo,

nedum etiam admittam te paratiim accusare judicem propterea crinrine inaiestatis,

quod contra constitutionem eum dicis pronuntiasse).

11. On the principle of philanlhropia cf. H. Hunger, . Eine griechische

Wortprgung auf ihrem Wege von Aischylos bis Theodoros Metochiles, Vienna 1963.

THE BYZANTINE TRIBUNALS (9th-12th C.)

169

tice: the citizens would be equal in the trials ( : cap. VIII).

In the oath which the high officers swore, honesty in justice is further elabo

rated: "I also swear to be impartial in deciding the cases of private indivi

duals, as well as those which concern the maintenance of public order, and

only to compel my subordinates to do what is equitable; to prosecute crimes;

and in all my actions to practice the justice which may seem to me proper;

and to preserve the innocence of virtuous men, as well as inflict punishment

upon the guilty in conformity to the provisions of the laws. I also swear (as I

have already done) to observe the rules of equity in all public and private

transactions" 12. In an earlier decree on the judicial oath of the year 529 (CJ

4, 1, 12) Justinian stresses that the measures introduced were not new or

unusual, but that they had been established by previous legislators: "For who

is ignorant of the fact that judges in former times could not accept the judi

cial office unless they had previously made oath that they would on all occa

sions decide according to the truth, and in compliance with the law?" To

secure correct judicial decisions, the emperor orders that in the future the

judges judge cases and pronounce their judgements only after the Holy Scrip

tures have previously been placed in front of the judiciary. For they "intro

ducecases to be weighed and determined with the assistance of God". Thus

the Christian form of the oath was introduced in judicial practice to guarant

ee

judicial integrity.

But it seems that these measures did not produce the expected results. A

Novel of Tiberius on the archons of the year 574 deals with the same pro

blem 13. The high public offices should be given to those who are honest and

for whom justice is of great importance (

); they should receive their office without any donation (

). The suffragium given to the emper

or's treasury ( ) is, however, permitted,

for the State benefits from this. This is justified by the concerns of the State

which are listed in order of priority: a) that the provinces be governed with

order and security and that they enjoy the justice of the archons; b) that the

taxes, which support the army, indispensable for the security of the State, be

thoroughly collected.

Another cause of the corruption of the judicial system was the pressure by

the powerful (potentiores ) exerted on both assessors and judges. It is

already attested in the sources of the early centuries 14. The Novel of Tiberius

on the "divine houses" reveals another kind of abuse. There were instances in

which the of these oikoi had started a judicial procedure against

12. ,

, '

. ,

" , ,

,

.

:?. JGH. . . -;.

14. (If. Jones, Later Homan Empire, op. cit., p. 50"2-4.

170

HELEN SARADI

others about peasants-coloni or other matters, and they were acting as judges

of their own cases. The legislator declares this inappropriate and illegal 15.

II. The middle byzantine period (7th-12th c.)

The ancient principle that governed justice in the earlier centuries, was

maintained in the evolving administrative system of the middle Byzantine

period. The judiciary was part of the imperial administration and thus highranking officers were assigned judicial responsibilities in the area of their

administrative competence. This is clearly attested in various sources. A

scholion in the Basilica 7, 1, 1 explains that judges were those who

hold the office of the judge, such as the droungarios, the epi ton kriseon, the

koiaistor, the eparch 16. According to the Peira each department of the imper

ialadministration was exercising judicial duties in the area of its compet

ence17. The documents of the archives of Athos offer specific examples. In a

judicial decision (eggraphon hypomnema) of the judge Nicholas of the thema of

Strymon and Thessalonica, in 995, there is reference to a judgement (krisis) of

Constantine Karamalos, protospatharios and megas chartoularios of the office

of the genikon in Constantinople, who was in charge of the fiscal register of

the empire. Although Karamalos did not hold the office of the krites, the text

alludes to his judgement as one of the politikoi dikaslai 18. In another decision

of the same judge of the year 996 we learn that by order of the emperor, the

krites of Strymon, Thessalonica and Drougouvitsia should compose a tribunal

with other officers of the imperial administration in order to judge a dispute

between the monastery of Polygvros and the tourmarches of the Bulgarians:

the tribunal is composed by a krites, tourmarchai, protospatharioi, two bis

hops,

spatharokandidatoi , one asekretes, droungarioi and one local archon 19.

These officers had knowledge of the case deriving from their competence in

the offices of the administration. Thus according to our text, the synedroi, the

witnesses and the two litigants formed a tribunal of great size ( ) 20. The defendant had to accept their decision on account of

the evidence of the eggrapha dikaiomata, the trustworthiness () of

the witnesses and the authority of the synedroi ( )21.

15. . Kaplan, Novelle de Tibre II sur les "maisons divines", TM 8, 1981, p. 239

(par. ): ' ( ).

16. " , ,

, .

17. Peira 51, 29: .

.

)

.

18. Actes d' lviron. . Des origines au milieu du xre sicle, d. J. Lefort, N. Oikonomids, D. Papachryssanthou, avec la collaboration d'H. Mtrkvu, Paris 1985,

no 9 1. 17: .

19. Ibidem, no 10 11. 11 ff.; 11. 28 ff .

20. Ibidem, 1. 17.

21. Ibidem, 1. 39.

THE BYZANTINE TRIBUNALS (9th- 12th C.)

171

As in earlier centuries, however, very often these officers did not have

sufficient experience in law. A practical solution to guarantee a functional

judicial system was to attach a professional judge () to the officers who

needed some support: Constantine Porphyrogenitos mentions the case of the

protospatharios Podaron who had shown remarkable bravery in the wars and

was very loyal to the emperor Leo VI, who promoted him to the office of

protospatharios of the . "But because he was illiterate ( v), by

order of the emperor a judge from the hippodrome used to go down and take

his seat with him in the and judge the oarsmen" 22. From the archives of

monasteries of Athos we know several cases in which professional judges were

attached to the tribunals of the offices of the administration"23. This practice

dictated by realism resulted a very flexible composition of the Byzantine

tribunals. Some sources draw a different picture of the appointment of judges

by revealing the personal motivations and the competition between officers

for the office of the judge. Thus, for example, a letter of Psellos addressed to

the judge of Thrace and Macedonia illustrates the competition of two officers

for the right to judge: Constantine Monomachos had offered Psellos the basilikaton of M adyta and the right to transfer it to whomever he wanted. The

beneficiary, who according to Psellos was a very honest man, was in competit

ion

with the tourmarches of Haplokonesos, because he had the right to judge

some of the lawsuits, while the tourmarches was trying to appropriate this

benefice24.

Particularly interesting is a scholion of Balsamon on the 15th canon of the

council of Carthage. Balsamon distinguishes three different types of judicial

officers: 1) the archons ( ) who

were not expected to possess legal training since they had other administrat

ive

duties; 2) the synedroi who assisted them with their legal expertise; 3) the

kritai whose office was to pronounce judgements (

) 2).

22. Constantine Porphyrogenitus. De Administrando Imperio. Greek Text, edited by

Gy. Moravcstk, Engl. transi, by R.J.II. Jenkins. Washington 1967, sect. 51 11. 100102. Cf. also Aik. Christophti.opoui.ou. -,

4, 1986-7, . 163 ff. and 168 on the evidence from the Byzantine seals.

23. Cf.. for example, Actes de Lavra. Premire partie des origines 1204, d. P. Lemerle, A. Guillou, N. Svoronos, avec la collaboration de D. Papachryssanthou,

Paris 1970, no 67 (1196): to the tribunal of the logothetes ton sekreton are attached three

kritai of the velum (11. 2-3, 93-94), and a notnophylax (11. 3, 94); no 68 (1 196): to the same

tribunal are attached five and four kritai of the velum (11. 2-3, 34-35), one dikaiophylajc

(1. 4) and one nomophylax (1. 35); Actes d'lviron II. Du milieu du XIe sicle 1204, ed.

,1. Lefort, . Oikonomids, D. Papachryssanthou, avec la collaboration de

V. Kravari et d'H. Mtrvij, Paris 1990, no 40 (1071): tribunal of the office of the

megas oikonomos of the Patriarch composed by ecclesiastics and the ostiarios and krites

Constantine Sideriot.es (1. 10 and p. 121).

24. C. Sathas, MR. vol. 5. p. 487.

25. G. Rhaii.es -M. Poti.es, . 3, Athens 1853,

. 339.

172

HELEN SARADI

In the 9th and 10th c. in the high tribunals of Constantinople (those of the

Prefect of the City, of the quaestor, of the epi ton deeseon) are attached the

symponoi as assessors, men with legal training who assisted the judges in

delivering their decisions. is attested in the treatise of Philotheos

as subordinate of the Prefect of the City26. Judges () of the ordinary

courts are also mentioned in each one of the fourteen regions of Constanti

nople.

In the office of the quaestor the antigrapheis probably had judicial

jurisdiction in minor cases27. Judges (kritai) were the judicial assistants to the

tribunals of the Prefect and of the quaestor28. The two major tribunals of the

capital, those of the velum and of the hippodrome are already mentioned in

the 10th c.29.

The importance of the synedroi in the judicial procedure is stressed in

several sources. According to a scholion of the Basilica 7, 1 the term paredria

itself suggests that the symponoi and the paredroi should only assist the jud

ges in their judicial work (...

' '

). Thus according to the Peira 51, 21 depositions of witnesses are

accepted and considered valid even after the death of the judge, if they were

written in the presence of the synedroi and signed by them. If they had not

been signed and sealed by a judge who had died in the meantime, they were

considered null. In an imperial semeiosis of Alexios Komnenos of the year

1082 the role of the assessors in the judicial procedure is once again specified.

The semeiosis deals with a trial regarding the nature of the document of a

deed of sale: should a document of private transaction be considered

according to the 44th Novel of Justinian, if it had only the signature of the

tabellio but not his komblcf The lawyer of the one of the litigants asked for a

comparison of the signatures which were on the document; when this was

presented, he argued that the semeioma with the comparison of the signatures

was not valid for it was not ratified by the synedroi'30.

Synedroi are also attested in two judicial decisions of the tribunal of

Constantinople in May and June 119631. President of the tribunal was the

megas logariastes and logothetes of the sekreta. It may be that this was an

extraordinary tribunal or that it was a tribunal of the logothetes of the sekreta,

similar to the tribunals of the different offices of the administration. These

26. On the symponos cf. . Oikonomids, Les listes de prsance byzantines des ixe et

x* sicles, Paris 1972, p. 179 1. 10, 320 and n. 189.

27. Ibidem, p. 322.

28. Ibidem, and n. 203, 204.

29. Ibidem, p. 323 with references to the first mention of these tribunals and to the

earlier bibliography.

30. JGR, 1, p. 298-302, esp. p. 299 ( ...

). For an analysis of

this document cf. D. Simon, Untersuchungen zum justinianischen Zivilprozess, Munich

1969, p. 354-9.

31. Ades de Lavra, I, no 67, 68. On these documents cf. P. Limerle, Notes sur

l'administration byzantine la veille de la IVe croisade d'aprs deux documents indits

des archives de Lavra, REB 19, Mlanges R. Janin, 1961, p. 258-268, esp. p. 261-5;

Actes de Lavra, I, p. 345 ff.

THE BYZANTINE TRIBUNALS (9th-12th C.)

173

documents are particularly interesting because they reveal the composition of

the Byzantine tribunals of the administration. In each one of the sessions the

number of the assessors was five, while that of the judges varies from seven in

the first session, to eleven in the second, thirteen in the third and nine in the

fourth. Although the four sessions took place within two months (May and

June) neither the judges nor the assessors were the same. The tribunal was

remarkably flexible in its composition. Among the assessors are important

officers such as the megas droungarios Antiochos, the primikerios Manikates,

the epi ton oikeiakon Theodoros Dalasenos and the pansebastos sebastos

Michael Belissariotes, known also from other sources; other lower officers

such as kouropalatai and basilikoi grammatikoi also participated. We do not

know whether they had been appointed assessors because some of them were

competent in legal matters or because of their familiarity with the system of

the imperial administration32. It is certain, however, that according to judi

cial decisions, in particular the Peira, various officers of the imperial adminis

tration often participated in tribunals as judges probably because they had

legal training33.

The flexibility of the Byzantine judicial system may also be seen in the

tradition that the emperor had the right to decide as he often did about

the composition of special courts to judge specific cases34.

In the provinces the judicial system had a slightly different structure. In

the provincial reorganization of the empire in themata, the judiciary was an

important consideration. It was clearly distinguished from the military admin

istration.

Thus according to a scholion of the Basilica in old times there were

two archons in each thema, the krites to judge the cases of civil law and the

doux for the military cases35. The strategos was, however, assuming greater

power in the administration of the themata. In the 10th c. the kritai of the

themata received new larger administrative charges, especially those of the

fisc, originally assumed by the protonotarios, while the power of the strategos

was reduced; he became the real governor of the provinces36. As Skylitzes

and Attaleiates note, the krites became 37.

Appeals could be made to the tribunals of Constantinople. In other sources

the krites of the themata is also called 38. In the 11th c. the power of

the sekreta was strengthened. These were independent administrative offices

32. Cf. the remarks of Lf.merle, Administration byzantine, op. cit., p. 264.

33. Oikonomids, Listes de prsance, op. cit., p. 323 ff.

34. Cf., for example, Actes de Laura, I, no 46 11. 43-44:

(1084); Actes d'Iviron, I, no 9 1. 4:

; no 10 (996); 33 (1061); 34 11. 14, 15; 35 1. 11 (1062).

35. ,

, ,

' . Cf. H. Ahrweiler, Recherches sur l'administration de l'empire byzantin

aux ixe-xie sicles, BCH 84 and Athens-Paris 1960, p. 69 ff.

36. Ibidem; Idem, Byzance et ta mer. La marine de guerre, la politique et les institutions

maritimes de Byzance aux vne-xV sicles, Paris 1966, p. 141. Cf. also Christophilopon.ou. , op. cit.. p. 172-4.

37. Attaleiates. Bonn. p. 183: Skylitzes, Bonn. p. 706.

38. Cf. Ahrweii.fr, Hecherohes, op. cit., p. 70.

174

HELEN SARADI

with judicial jurisdiction (, ) assuming also other administ

rative functions. The civil administration was reinforced not only in the

central government but also in the themata, where the kritai assumed the

economic and judicial power. Constantine Monomachos created a new sekreton of justice ( ) which had jurisdiction

and control over the judges of the themata39. In the 11th c. there were four

high tribunals in the capital: that of the Eparch whose jurisdiction had been

reduced to cases of the professionals, of the quaestor, of the droungarios of the

velum, and of the epi ton kriseon40. In the reorganization of the imperial

administration under the Komnenoi, the praitor-kriles of the themata received

the judicial power in the provinces, while the doux-anagrapheus assumed the

civil and military41.

With reference to the application of law by the judges, we have seen that

the imperial constitutions of the earlier centuries had recognized a certain

degree of freedom of the judges in their interpretation of the laws. Based on

the existing Byzantine judicial decisions, contemporary legal historians have

discerned a major problem in the application of justice, namely the "flexible"

use of the laws by the Byzantine judges and they have concluded that the

Byzantine judges did not always justify their decisions by the existing imper

iallegislation, but that they interpreted the laws according to the tradition

or to concepts such as , , 42; or that they used

constitutions which had already been abolished to justify their judicial deci

sions. It has been suggested that the gap between judicial practice and the

laws was not the result of practical reasons, such as the poor training of the

39. Attaleiates, 21-22:

, '. Cf. Ahrweii.er, Recherches, op. cit.,

p. 70-1; Idem, Byzance et la mer, op. cit., p. 141; N. Oikonomids, L'volution de l'o

rganisation

administrative de l'empire byzantin au xi'" sicle (1025-1118), TM 6, 1976,

p. 134, and the different view of Christophilopoui.ou, , op. cit.,

p. 174-7. In a hypomnema of the protos of Mount Athos (1057) the judicial decision of

this sekreton is called : Actes de

Saint-Pantlmn, ed. P. Lemerle, G. Dagron, S. Cirkovic, Paris 1982, no 5 1. 9.

40. Oikonomids, L'volution de l'organisation administrative au xic s., op. cit.,

p. 133-5.

41. On the praitor-krites cf. Ahrweiler, Recherches, op. cil., p. 77. On the doux cf.

J.-C. Cheynet, Du stratge de thme au duc: chronologie de l'volution au cours du

xie sicle, TM 9, 1985, p. 181-194. On the provincial tribunals and the provincial judi

cial procedure in the decisions of Demetrios Chomatianos cf. D. Simon, Byzantinische

Provinzialjustiz, BZ 79, 1986, p. 310-343, with particular attention on the bishop's

jurisdiction; on the praitor, p. 338-9.

42. On cf. C. Cupane, Appunti per uno studio dell'oikonomia ecclesiastics

a Bisanzio, JOB 38, 1988, p. 53-73; N. Oikonomids, The "Peira" of Eustathios Rhomaios: an Abortive Attempt to innovate in Byzantine Law, FM VII, Frankfurt am

Main 1986, p. 185; H.G. Beck, Nomos, Kanon und Staatsraison in Byzanz, SB Vienna,

384, 1981, p. 40 and n. 97; G. Weiss, Hohe Richter in Konstantinopel. Eustathios

Rhomaios und seine Kollegen, JOB 22, 1973, p. 138; D. Simon, Bechlsfindung am byzan

tinischen

Beichsgericht, Frankfurt am Main 1973, p. 22 ff.

THE BYZANTINE TRIBUNALS (9th-12th C.)

175

judges, their corruption, or problems of the administrative system, but rather

the particular concept of the function of the legal texts in Byzantium. Thus

according to this view the Byzantine judges regarded their work as a political

act; their power derived from their appointment by the emperor and by his

moral character43. Therefore what actually mattered was not legal training,

but rather talent, intelligence, knowledge of rhetoric and experience in legal

cases. On the other hand, there is no doubt that most of the surviving judicial

decisions were based on the existing legislation. This of course provided pro

tection

to the judges in case they were reproached for unfair judgements.

Thus it has been suggested that the legal texts were actually considered as a

collection of lopoi from which the judges were taking their arguments44. A

historical interpretation offers another explanation of the phenomenon: prac

tical problems in the application of the legislation which in many cases had

become obsolete in the middle Byzantine period, obliged the judges to adapt

their decisions to the new historical reality 4).

While the Byzantine judges were permitted to bend the laws, to be selec

tive in choosing the decrees from the existing vast imperial legislation and to

apply them to individual cases according to the principles of or

, corruption of the judicial system, namely the venality, the disho

nesty and the incompetence of the judges, directly related to the social and

administrative structure of the empire, was unacceptable. This study will

focus on how sensitive the State was to these problems and how it tried to

solve them.

In the middle Byzantine period the office of the judge is defined in various

juridical texts; his obligations and the standards of the profession are also

described. Statements about judicial corruption are to be found in all juridi

cal

texts, but it is in the Ecloga of Leo III that it is defined with precision as

the intentional distortion of the law to serve the personal aims of the judge.

Furthermore it is placed in a social context, as the exploitation of the poor

() by the powerful (). Both the definition of and the approach to

judicial corruption are entirely new. According to our text the judges should

stay away from all human passions and pronounce their judgements after

sound reflection; they should not fail to care for the penetes nor allow that the

dynatoi remain unpunished46; nor should they pretend that they admire jus

tice and equality, while in practice they prefer injustice and covetousness for

this is beneficial to them; if they judge cases in which the one of the litigants

43. Ibidem, p. 16ff.

44. Ibidem, p. 23 ff.; Sp. N. Troianos, 8, Athens 1986,

p. 36.

45. Oikonomides, The "Peira" of Eustathios Rornaios, op. cit., p. 183-190.

46. Ecloga. Das Gesetzbuch Leons III. und Konstantinos' V., ed. L. Burgmann,

Frankfurt am Main 1983, p. 164:

,

... On the oppression of the penetes by the dynatoi cf.

II. Saradi, On the "Archontike" and "Ekklesiastike Dynasteia" and "Prostasia'" in

Byzantium with Particular Attention to the Legal Sources. A Study in Social History

of Byzantium, By-. 64. 1994, p. 69-117, 314-351.

176

HELEN SARADI

is a privileged man and the other a poor one, they should regard the two

litigants as equal, by taking away from the one who has more the amount

that the victim of injustice had lost47. In the following passage the text

defines judicial corruption as: 1) bribery; 2) favour toward a friend48;

3) defense against someone else's hostility; 4) fear of the power of a dynatos (

, '

). Two quotations from the Bible justify why judges must endorse the

principle of justice. In this passage judicial corruption is defined in social

terms (bribery, personal motivations, pressure by the powerful). Further,

however, the application of justice is interpreted as a problem of comprehend

ing

law: judges who understand what is just ( ) apply

justice, while others on account of their intellectual limitations (

) are unable to pronounce justice ( ).

Thus according to the Ecloga judicial corruption was a social problem, a

problem of social relations; although personal and social forces are recognized

as operating behind the incompetence of judges (desire for money, personal

relations, influence of the powerful), the legislator did not try to solve the

problem with social measures; personal motivations and social factors could

operate in the application of justice because the judges were not able to

comprehend justice. The question of the legal training of the judges is not

raised; nor is the need felt for a judicial body, separate from the imperial

administration. According to our text the judges who were thoughtful had

correct judgement ( ) and possessed clear knowl

edge of real justice ( ); they should

demonstrate correct judgement and apply justice. It is to those judges that

Christ, the power and wisdom of God, donates the knowledge of justice and

reveals the things which are hard to find out (

, ,

). It is God who gave the

knowledge of justice to Solomon when he pronounced his judgement in the

famous case of the two women and the child: since no one of them could

support her claim with evidence or witnesses, he made his decision by provo

kinga reaction of maternal feelings.

The judges appointed by the emperor should think of all these. The emper

orsin order to correct judicial corruption as described in the above terms,

47. ,

, ' ,

,

, . For a

comparison of the Ecloga's prooimion with earlier ecclesiastical texts cf. II. Saradi, op.

cit., p. 85.

48. Favour to friends is defined as a form of judicial corruption in earlier centuries.

Cf., for example, I. Hahn, Immunitt und Korruption der Curialen in der Sptantike,

W. Schuller (ed.), Korruption im Altertum, p. 179-199, esp. p. 187 ff. From the eccle

siastical

literature cf., for example, John Chrysostom, PG 51, col. 23: ... ,

,

, .

THE BYZANTINE TRIBUNALS (9th- 12th C.)

177

decide to impede the give-and-take () of the judges. They order that

the judges receive their salary from the imperial sakelle, so that they are not

paid by the litigants49. This measure is along the lines of Justinian's

approach to the same problem; it is, however, justified with a quotation from

the Scriptures ( "

,

).

The theme of justice is also central in the prooimion of the Procheiros

Nomos. Many quotations from the Scriptures justify the significance of jus

tice in the context of religious tradition as well as in terms of social relations.

God is worshipped first and foremost with justice50. The divine origin of

justice is stressed ( ,

...); law has been given to men by God for assistance (

)01.

The prooimion of the Epanagoge is written in a more elaborate style, while

reference to the religious concept of justice is minimal52. Some sections of the

Epanagoge deal with the judges. The 6, 4 stipulates that the archon cannot

appoint someone as courator or special judge (

). The 7, 1 stipulates that the judges should not receive money

for their judicial decisions, not even by claiming a customary tradition (

)03. They had the permission of the emperor to examine the

unjust actions of magistrates and punish them by depriving them of their

office, for more or less they represented the emperor in the provinces. And as

they were not allowed to make any illegal profit ( ), the

emperor orders that they be honoured and respected. The sections 11, 4-9

deal with appeals against judicial judgements which are defined as a litigant's

allegation against a judge that he had not been judged properly (

: 1 1 , 4). The

decisions of lower courts were subject to appeals to the higher courts, those of

the emperor, the patriarch, the eparch and the quaestor. The lower the court,

the more it needed assistance, and most of the judgements of the lower courts

had to be corrected ( ,

).

The problem of judicial corruption was addressed directly by the emperors

of the Macedonian dynasty. According to the historiographical sources Basil 1

appointed incorruptible judges paid by the State aiming to guarantee equa-

49. Ecloga, p. 166.

50. JGFt, 2, p. 114: ,

.

51 Ibidem, p. 115.

52. Cf. J. Scharf, Photios und die Epanagoge, BZ 49, 1956, p. 385-400; Idem. Quel

lenstudien

zum Prooimion der Epanagoge, BZ 52, 1959, p. 68-81.

53. On cf. Oikonomids, Listes de prsance, op. cit.. p. 88 n. 28; St. Perentides, ; "",

. , 2, . 476-485. For the earlier legal tradition cf. . Schmiedel, Consuetudo im klassischen und nachklassischen rmischen Becht. Graz-Kln 1966.

esp. p. 122-7 for the Basilica.

178

HELEN SARADI

lity everywhere in the empire and to prevent the abuses of the penetes by the

wealthy54.

The next text that deals directly with judicial corruption is a decree of

Leo VI. The title reveals the aims of this decree: it is a condemnation of the

judges ( '

). The legislator believes that no judge would ever go so

astray that he would pronounce a judgement against the laws. If he slips to

such a degree of vanity, and he is caught, he will be punished according to the

laws. If he escapes the attention of the State, he will receive divine punish

ment. To make the stipulation more secure, the legislator ratifies it with

maledictions. Thus corrupt judges will find themselves fighting against God,

and the celestial and incorporai powers will fight against him; his life will

terminate early, and he will be punished in the future life; fire will destroy the

foundations of his house, and shame and disgrace will be brought on his

descendants and they will be in need of the bare essentials (literally, bread)

for having rendered the flexibility (literally, ) of the law subservient

to twisted judgements55. This text is extremely important for our study for

two reasons. First it clearly distinguishes the right of the judges to interpret

the laws freely, namely the of the laws (probably implying the prin

ciples of and sanctioned by the earlier legislation), from

illegal judicial decisions dictated by personal interest. Second, it does not

repeat the earlier laws applying to corruption of judges. These are referred to

indirectly. The legislator was not concerned to secure the enforcement of

these laws, but rather to invent new and more secure means to guarantee an

incorruptible judicial system, that of divine punishment, a warranty of rel

igious

origin consolidated with maledictions, particularly for corrupt judge

ments which remained undetected. We should note that maledictions are

very rare in the imperial constitutions56. Obviously this approach failed to

uproot the causes of judicial corruption.

54. Theophanes Continuatus, p. 258-261 = Skylitzes, ed. J. Thurn, p. 132-133:

.

55. JGR, 1, . 188-9 = . Noaiij.es and A. Dain, Les Novelles de Lon VI le Sage,

Paris 1944, p. 377:

.

,

. "

.

'

' .

56. Cf., for example, the oath of the archons cited in the Novel 8 of Justinian (a.

535): ,

'

. Cf. also Procopius, need. XXI,

17; Novel 54, 2 (a. 537):

THE BYZANTINE TRIBUNALS (9th-12th C.)

179

In the Novel 97 magistrates when receiving their office, and judges when

appointed to judge a case, should give an oath that they would honour the

truth;>7. With another Novel of Leo VI other irregularities of the judicial

system are corrected. In order to avoid suspicion and confusion (

) in the trials, the judges should sign the documents of their deci

sions with their own signature08.

These texts refer to judicial corruption in a more or less general way. The

imperial constitution which deals with a specific problem in the application of

justice, is a Novel of Constantine Porphyrogenitos of the year 947 on the

pre-emption right of the penetesrM. The emperor reveals that the previous

legislation on the pre-emption right had not been enforced because the judges

pronounced their judgements under pressure by the dynatoi rather than

according to their own will; their decisions were offering various accommodat

ions

in various situations ( , , ' )60.

Later in another Novel of Romanos this situation is described with an even

stronger vocabulary: "We must beware lest we send upon the unfortunate

poor the calamity of law-officers, more merciless than famine itself"61. Based

. On the maledictions in the Novels of Justinian of.

S. Puliatti, Bicerche sulla legislazione "regionale" di Giustiniano, Milan 1980, p. 49

n. 98. On the maledictions in the early Christian sources cf. S. P. Ntantes, '

. '

, Athens 1983. Cf. also Ph. Koukoui.es.

, 3, Athens 1949, . 326-346. For the later Byzantine legal

sources cf. H. Saradi, Cursing in the Byzantine Notarial Acts. A New Form of Warr

anty, (forthcoming).

57. Noaili.es- Dain, Leu Novellen de Lon VI. op. cil., p. 317-9.

58. Ibidem, p. 181. It is particularly in judicial decisions of the 10th century, in

accordance with this regulation of Leo VI, that judges state that they had signed with

their own signature and they had sealed their decision: Actes d'Iviron, I, no 1 11. 20-21,

22 (927); no 9 11. 54, 55 (995); no 10 11. 60-62 (996).

59. On the pre-emption right of the penetes cf. Zachari von Lingenthal, Ges

chichte

des griechisch-rmischen Rechts, Berlin 1892, p. 236-248; G. Ostrogorsky, The

Peasant's pre-Emption Right. An Abortive Reform of the Macedonian Emperors, JBS

37, 1947, p. 117-126; Idem, Agrarian Conditions in the Byzantine Empire in the Middle

Ages, The Cambridge Economic History of Europe, 1966, p. 205-234, 774-9; Idem, Quel

ques problmes de la paysannerie byzantine, Brussels 1956; P. Lemerle, Esquisse pour

une histoire agraire de Byzance: les sources et les problmes, Bvue historique 219, 1958,

p. 32-74, 254-84; 220, 1958, p. 43-94; A. Kazhdan, Social' nyj sostav gospodstvujuscego

klassa Vizantii xi-xu , Moscow 1974; R. Morris, The Powerful and the Poor in the

Tenth-Century Byzantium: Law and Reality, Past and Present 73, 1976. p. 3-27;

H. Saradi. On the "Archontike" and "Ekklesiastike Dynasteia" and "Prostasia" in

Byzantium, op. cit.. p. 90 ff.

60. JGR. I. p. 215.

61. Ibidem, p. 242: transi. Ostrogorsky. The Peasants Pre-emption Right, op. cit..

p. 122.

180

HELEN SARADI

on a judicial decision from the archives of Lavra, Ostrogorsky tried to show

the legal ways the judges had devised to circumvent the law62.

It should be stressed that the judges belonged to the class of dynatoi; these

are defined in one of the Novels of Romanos Lecapenos of the year 934 as

those who, if not by themselves, then by using the dynasleia of others with

whom they were acquainted, were able to inspire fear in those who were

selling properties or to promise a certain benefit in return for the transac

tion63. Other Novels of the same series defined the dynatoi in terms of rank in

the imperial administration or of wealth: by using political and economic

power the members of the upper class could exercise pressure on the penetes

for their own benefit. Although there is no explicit reference to the judges as

dynatoi in the Novels of the emperors of the Macedonian dynasty, there is no

doubt that they were part of that class64. In fact the Peira supports this

conclusion. In 7, 12 is discussed a case of a kriles who made an arrangement of

dialysis (settlement of a dispute) with a peasant, who later contested it. The

peasant is described as one of the penetes, while the judge as one holding an

office ( )65. The 42, 18 deals with the abuses of the protospatharios Romanos Skieros against some peasants. Later they reached an agree

ment of dialysis which the peasants contested on account of pressure exerci

sed

on them by the judge (krites). Eustathios Romaios ordered that, if the

peasants were able to prove that they had been forced to the agreement of

dialysis by the krites, the agreement should be declared null66. The sources

attest that particularly in the 11th c. the power of the provincial judges was

increasing. In a hypomnema of the judge Constantine Kamateros of the year

1037 from the archives of Docheiariou, unique in our sources, the judge threa62. Ibidem, p. 119-122. Cf. also the opposing view of Lemeri.e, Esquisse pour une

histoire agraire, op. cit., p. 71-4; Idem, The Agrarian History of Byzantium from the

Origins to the Twelfth Century. The Sources and Problems, Galway 1979, p. 157-160.

63. JGR, 1, p. 203.

64. Ibidem, p. 209, 213, 216, 217, 223, 265. Cf. also N. Svoronos, Remarques sur la

tradition du texte de la Novelle de Basile II concernant les puissants, Recueil des Travaux

de l'Institut d'Etudes byzantines, VIII, Mlanges G. Ostrogorsky, II, Belgrade 1964, p. 427434

Dynasteia"

(= Var. and

Repr."Prostasia"

no VIII), in

andByzantium,

H. Saradi,op.Oncit.,

thep."Archontike"

90 ff., 100, 108

andand"Ekklesiastike

n. 173.

65. JGR, 4, p. 29: ,

.

66. Ibidem, . 177: ,

. Another case of abuse of a krites toward a penes is attested in Fr. Trinchera,

Syllabus graecarum membranarum..., Naples 1865, no 184 (p. 24). Cf. also S. Vryonis,

The Peira as a Source for the History of Byzantine Aristocratic Society in the First

Half of the Eleventh Century, Near Eastern Numismatics, Iconography, Epigraphy and

History. Studies in Honor of George C. Miles, Beirut 1974, p. 279-284, and D. Simon's

remarks on the "social character" of the tribunal of Eustathios Romaios: Rechts findung

am byzantinischen Reichsgericht, 10 (Das Hippodrom prsentiert, sich demnach als Klas

sengericht.

Klassengericht, das muss vielleicht hervorgehoben werden, ist nicht im

Sinne der politischen Propagandistik formuliert, etwa: Justiz als Unterdrckungsins

trument

via korrupter Rechtsanwendung, sondern aus soziologischer Sicht, d.h. be

stimmte

Faktoren haben die Chance der verschiedenen sozialen Schichten, vor diesem

Gericht ihre Interessen durchzusetzen, ungleich gestaltet).

THE BYZANTINE TRIBUNALS (9th-12th C.)

181

tens with his wrath whomever would not respect his decision (

) b7. In the 12th c. Balsanion in his commentary

on the 3rd canon of the council of Saint Sophia uses terms disclosing the

political power of the judges: and 68.

Private collections of laws are of particular interest since they were compil

ed

to be used by legal professionals; thus the criterion of selection expresses

the established practice. In the Epitome69 the regulations on judges are

included in the section on archons (titl. 14:

). This underlines the administ

rativenature of the office of the Byzantine judge. Constitutions from various

legislative texts, particularly the Justinianie legislation, are contained in this

title of the Epitome. The 14, 10 derives from the titl. 4. cap. 3 of Athanasius

which stipulates that those who hold an office should avoid any profit, they

should be satisfied with the public allowances of rations (), for they

had received the office freely. Influence of powerful persons on judicial deci

sions is clearly suggested in the cap. 21 which repeats the CJ 2, 13: whoever is

represented by a dynaton prosopon in a trial or hands over to him his

complaint should lose his case in the lawsuit. The cap. 34 repeats the CJ 1, 45,

1 that those who, while holding an office are engaged in a lawsuit, should not

sit with the judge nor should they have the possibility of doing this. The cap.

35 repeats the CTh 17, 4 that the archon must pronounce his judgement on all

cases in a brief period of time and with fairness ( ). The

cap. 37 stipulates that the litigant who has entrusted a lawsuit to a judge is

not allowed to transfer the case to another judge on the grounds that the

former was not appropriate. Only after his condemnation, if he wanted, could

he appeal to another tribunal. The cap. 43 forbids that a person who had

acted as someone's lawyer to act as judge in another case of the same person

{Dig. 2, 1, 17) and as in the CJ 2, 6, 6 no one could act as a lawyer and judge

for the same case. If he does so he will have to pay 10 pounds of gold (CJ 1,

51, 14). The cap. 49 repeats the CJ 3, 1, 11 (a. 527?) that the judges should

pronounce their judgements according to what appears to them to be right on

the basis of the existing laws ( ), and they should not fear imperial deci

sions commending an illegal action, for such an order would be invalid. Thus,

67. Actes de Docheiariou, ed. N. Oikonomids, Paris 1984, no 1 1. 22 and p. 50. Such

a menace, however, was clearly against the law. A scholion of the Epitome 14, 33

specifies according to CJ 7, 57, 1 , 2 that the judge's threat does not count for a decision:

.

/ (J(Fi, 4, . 360 . 70).

68. Rhalles-Potles, op. cit., 2, p. 71: ,

. Cf. . Saradi, The 12th Century Canon Law

Commentaries on the : Ecclesiastical Theory vs. Juridical Practice,

Byzantium in the 12th Century. Canon Law, Slate and Society, ed. N. Oikonomides,

Athens 1991, p. 375-404.

69. On the Epitome cf. A. Schminck, Studien zu mittelbyzantinischen Rechtsbcher,

Frankfurt am Main 1986, p. 109-131: ,1. Maruhn, Der Titel 50 der Epitome, FM 111,

Frankfurt am Main 1979, p. 194-210.

182

HELEN SARADI

while the existing laws offer the guidelines, the application of justice is left

entirely to the judges, and it is certainly placed above any illegal imperial

decree. The cap. 51 reproduces the Dig. 1, 3, 24: the judge should not pay

attention only to a detail of the law, but he should examine the law as a

whole ( ). Bribery is forbidden and the judge who

was bribed should return the amount he had received ( ).

The cap. 54 refers to invalid ownership sanctioned by unjust judicial decisions

( ). The lack of experience and injus

ticeof a judge is also mentioned in the 2, 10 ( ).

The cap. 14, 55 reproduces the CJ 7, 45, 15 allowing the judge freedom in

selecting the cases he wanted to judge. He could deal only with the cases he

wanted, while he should refer the others to superior judges. The cap. 63 (= CJ

3, 4) recognizes different areas of jurisdiction of judges ().

In the Basilica are included various ancient constitutions on judges and

the judicial procedure. The 7, 1, 1 reproduces a constitution of Zeno in the CJ

1, 51, 13 that the symponoi should never make judgements without the

archons by signing on their behalf. A scholion in the Basilica 7, 1, 3 explains

that and were for the judges (those who

had the office to judge, such as the droungarios, the epi ton kriseon, the

quaestor, the eparch). The duty of the symponoi was not to judge, but to

work with the archons ( ,

). Another form of judicial irregularity was to act at the same time as

lawyer and synedros by more than one archon (Basilica 7, 1,2 = CJ 1, 51, 14).

The Novel 60 of Justinian restricting the judicial initiatives of the paredroi is

included in the Basilica 7, 1, 3 (= Syn. Bas. , 33, 28). Of interest to this

study is the 7, 9 forbidding the dynaloi to offer their protection to the lit

igants

or to make agreements on their behalf (= CJ 2, 13, 1-2), and the 7, 10

forbidding the defendants to use the names of dynaloi in expectation that

they would influence the judicial decision, and to attach titles of ownership in

their name (= CJ 2, 14, 1).

The Novels of the 10th c. rule on other kinds of disfunctions of the judicial

system. A first Novel of Constantine Porphyrogenitos (945-959) regulates the

salaries of the judges and their subordinates70. Covetous revenues even if

were received according to an ancient custom, are forbidden. The judges of

the themata should not receive more than 3 nomismata for each pound of gold

of the value of the disputed property. The legislator explains that this fee

applies obviously to the wealthy litigants. According to the Justinianic legis

lation the judges received two nomismata from each one of the litigants at

the beginning of the lawsuits and two at the end (a total of eight nomismata)

only for the cases of over 100 nomismata, plus a salary from the imperial

treasury. Justinian was hoping that the salary would eliminate judicial bri70. JGR, 1, p. 218-221. On the fees of the judges according to the Justinianic legisla

tioncf. Novel 82, cap. IX (= Basilica 7, 1, 12; Syn. Basil. , 35; cf. also Epanagoge 17,

1). Another attempt to regulate the salaries of the judges from the imperial treasury is

attested in the Ecloga, pr.\

,

.

THE BYZANTINE TRIBUNALS (9th-12th C.)

183

bery ( .

, '

...:

Novel 82, cap. IX). Constantine Porphyrogenitos specifies that the judges

should spend this money for themselves and for their subordinates. Any addi

tional request was unacceptable. In any case they should never demand more

than 100 nomismata as (the fee paid by the litigants), except for a

travel allowance of the executor of the judicial decision (). The pea

sants and the other peneles should pay only one nomisma per each pound of

gold of the value of the disputed property. Favourably are treated those who

had been victims of clear aggressive injustice, namely if there was not a case

of . The judges and their subordinates should administer jus

tice "with their hands clean" ( ,

)'1. The Novel also specif

iesthe fee of the secretaries who produced the written records of the jud

gements

in the provinces ( ) and in Constantinople. The sec

tion 2 regulates the payments for the registration of wills at the office of the

quaestor. The section 3 is a regulation of the payment of the scribe. His

functions are defined: he was not a judge with full powers (

), he was placed lower than the judges of the themata and even the

antigrapheis and he handled the cases of minors72. The 4th section of the

Novel stipulates that the judges of Constantinople (polilikoi) should not

receive anything for any reason whatsoever (

,

') '^.

A second Novel of Constantine Porphyrogenitos on the same subject was

issued later. It appears that the first Novel had caused confusion regarding

fees paid by the litigants, the so-called eklagialika1A. Covetous and illegal

profit was the reason for the abnormal situation described in the prooimion of

the Novel. The text speaks of the successive transfer of lawsuits to other

judges with the obvious result of a dramatic increase in the fees of the lit

igants.

Thus the emperor ratifies the earlier Novel: the judges should not

make any profit from the above mentioned situations either for themselves,

or on behalf of their secretaries with the exception of their soldiers ()75. Particularly the notarioi (secretaries) should be paid by the litigant

who won the case: thus the judges would be incited to deliver their decisions

in time.

71. JOB, 1, p. 219.

72. Ibidem, p. 220.

73. Ibidem.

74. Ibidem, p. 227-9.

75. On the cf. Oikonomids, Listes de prsance, op. cit., p. 86 n. 25.

In the 11th c. the of the kriiai were responsible for abuses (illegal exac

tions) over the peasants: Michaelis Pselli scripta minora, ed. G. Kurtz, F. Drexl,

Milan 1936, 1941, vol. 2, p. 144:

.

, .

184

HELEN SARADI

It is particularly in the 1 lth c. that various sources manifest a great aware

nessof the complex problems of the Byzantine judicial system. They are

addressed directly and with frankness. Even in documents of the administrat

ion

which follow standard clichs, there now appear expressions either stres

sing the qualities of the judges or indicating their failings. For example, in a

graphe with which the empress Theodora ordered a judge of the velum, Voleron and Strymon to judge a dispute between Iviron and a monk, she

addresses him as 76.

Other sources, such as the Strategikon of Kekaumenos, offer several specif

ic

examples of judicial corruption and they draw a more complex picture:

they underline the divine origin of justice, they define justice as a religious

obligation of the judges to protect the poor; they place justice in the context

of aristocratic ethics. One of the obligations of the strategos was to keep an

eye on the judge, in case his judgements were not just. The strategos was

advised to intervene in any lawsuit in which injustice was committed77. By

interfering he was acting according to divine orders. Thus God would support

him. Examples from the New Testament justify such initiatives of the strate

gos.The duty of the judge to take the initiative and apply justice where it

was needed, was not an obligation toward the State or the society; rather it

was a duty toward God78. His decision should be in accordance with the

principle of philanthropia 79. Bribery of the judges of the themata is stressed as

very common. The judge who received gifts put himself in the darkness of

ignorance ( )80, even if he was very wise and knowl

edgeable.

Bribery would lead to unjust judgements. Judges should be satis

fiedwith what they were entitled to get. For they had not been appointed to

the office in order to accumulate wealth, but rather in order to give justice to

those who had been victims of injustice ( ). The judge

should not pronounce a judgement on account of friendship. If a charge was

brought against one of his friends, he should resign from the case, for it is

expected that he wouldn't be impartial. The pride and dignity of the judge in

the context of social ethics are presented as the first reason why he should

reject such cases ( ); on the other hand it should be expected that

his friend would be sentenced by the politikoi judges. Here it is rather the

honour of the aristocrat instead of the high value of justice and his legal

obligation to meet the standards of the profession that matter. If the judge's

motivation was to benefit from presents, this would incite him to make a

dishonest judicial decision, for the judge would consider those willing to offer

76. Actes d'Iviron, II, no 31 I. 10 (1056). Cf. also no 34 11. 1-3:

, , , ,

,

, .

77. G.G. LiTAVRiN, Soveti i rasskazi Kekavmena: socinenie vizantijskogo polkovodlsa

XI veka, Moscow 1972, p. 118: , ,

,

, .

78. Ibidem, p. 118-120.

79. Ibidem, p. 120 11. 17-18: .

80. Ibidem, p. 126.

THE BYZANTINE TRIBUNALS (9th-12th C.)

185

presents as just, while those refusing to bribe him would be regarded by him

as unjust81. This statement is supported by a quotation from the Old Testa

ment. Further Kekaumenos advises the strategoi and the krilai not to receive

their office by paying xenia (friendly gifts). For whoever acts in this way, will

later try to make up the money he had paid. Thus he would be hated by

everyone and he would become a burden (

) 8'2.

It was common knowledge that promotions to the positions of judges were

not made on the basis of merit. Kekaumenos describes how incompetent

judges who could be subjects of laughter ( ) were prosper

ing,while others wise and honest ( ) were neglected by

the emperors83. Kekaumenos advises the future strategos that he secure that

the judges pronounce their judgement fearing God and according to justice

( )84. For it was a common practice

that they ask from the litigants a fee larger than the amount of the value of

the lawsuit and not only in cases of debts but also in other kinds of charges85.

Some problems of the Byzantine judicial system are illustrated in a unique

way in the letters of Michael Psellos. Psellos exercised his influence in favour

of his friends and other individuals he supported, in several letters addressed

to judges86. This appears to be a form of "prostasia" (patronage), attested in

Byzantine sources in various forms87. In this respect some of Psellos' letters

are particularly interesting. Psellos is asking the judges to favour his protgs

on account of friendship, explicitly expressed88. In a letter to the krites of

Opsikion he asks that the judge show himself a true friend and precise judge

in his decision, that he should strengthen friendship with justice and viceversa89. In another letter, friendship is placed above the laws ( ,

)90. But Psellos is not consistent: in another case he

declares that friendship carries a great weight in a most just balance only if

81. Ibidem, p. 128.

82. Ibidem, p. 236.

83. Ibidem, p. 276.

84. Ibidem, p. 284. Similar statements are found in other strategika: G.T. Denn

is-E. Gamillscheg, Das Strategikon des Maiirikios, Vienna 1981, p. 70 11. 36-38:

.

85. LiTAVRiN, Kekavmena, op. cit., p. 284:

, .

86. Psellos, Scripta minora, op. cit., 2, ep. 50-52, 66, 77, 81-84, 99, 107, 140, 142,

150-2, 154, 162-3, 166, 171-2, 182, 221, 243, 247, 250-1.

87. Cf. H. Saradi, On the "Archontike" and "Ekklesiastike Dynasteia" and "Prostasia" in Byzantium, op. cil., p. 314 ff. For references to the sources of late antiquity cf.

Jones, Later Roman Empire, op. cit., p. 503-4.

88. Psellos, Scripta minora, 2, p. 84 11. 4-6 ( ... ,

), . 90 1. 13 ( ), . 100 1. 6 ( ), . 112 1. 24

( ), . 113 1. 24 ( ), . 176 11. 10-11 ( ,

), . 177 11. 10-11, . 195 1. 28, . 263 1. 23.

89. Ibidem, p. 128 II. 3-7.

90. Ibidem, p. 169 11. 18-19.

186

HELEN SARADI

combined with justice91. In another letter, however, he also stresses that

bribery of judges is forbidden and that they should not favour individuals in

the trials92.

In some other letters Psellos' interference is more carefully formulated. In

one such letter he is asking a judge to make a decision favourable to a poor

man: Psellos is not demanding anything specific, such as to judge the litigant

in a particular way, or to keep away the person who acts despitfully, or to

stop the neighbour who is doing wrong to him, but to assist him when he finds

himself in an annoying and painful situation 93. In a similar way is formulated

another letter to a judge in favour of a friend of his father. Psellos is convin

ced

that the judge will deal with the man's affairs in a spirit of justice; thus

he is only asking him to show mercy and to treat him gently as a judicial

officer ( , ) 94.

Psellos asks the judge of Philadelphia to consider their friendship in a

judicial decision: he may, however, wish to choose a way more appropriate to

the law and justice ( ). For a reexamination of a

case a second or third time may prove that the first decision was superficial

(), not taking into consideration the underlying basic elements

of the case. An argument, which Psellos admitted was sophistic, was invented

to persuade the judge that he should be generous toward the local inhabi

tants: Aristotle and Plato were not reluctant to change their earlier views. He

advises the judge to compare his friendship to the correct "dikaion".

Although he declares he allows him to choose the laws rather than friendship

with him, he finally insists that the judge contrive something favourable to

the people95. In another letter Psellos advises a judge to reserve the right to

judge cases which are beneficial to the local inhabitants. For he should not

accept to be the judge of all cases, nor should he deny the right of a lawsuit to

plaintiffs96.

The letters of Psellos are also interesting from another point of view: they

define the generally accepted qualities of the judges. In a letter to the Doukas

Caesar, Psellos recommends a judge on account of his qualities: he had shown

that he had a judicial soul ( ) for, while he was holding the

office of kourator, he dealt with the matters arising with precise justice97. The

integrity and virtue of the judge of Philadelphia (he was praised by the

people of the area)98 did not impede Psellos to ask for a favour. The qualities

of a judge are defined by Psellos as benevolence, wisdom and justice (

)99, while judicial power is placed next to thinking with preci91. Ibidem, p. 192 11. 7-10: , (

) . .

92. Ibidem, . 191 II. 21-22:

.

93. Psellos, Sathas, op. cit., p. 489.

94. Ibidem, p. 258 (no 20).

95. Ibidem, p. 460-1.

96. Ibidem, p. 395.

97. Ibidem, p. 399.

98. Ibidem, p. 460.

99. Ibidem, p. 274.

THE BYZANTINE TRIBUNALS (9th-12th C.)

187

sion ( )100. In other

letters are stressed virtue, a straightforward attitude, good will, kindness, a

philosophical soul and precision101. Philanthropia is often emphasized as

more important than the strict application of law10'2. In a letter addressed to

the proedros Constantine, the niece of the patriarch Michael, Psellos

reproaches the proedros for applying the law, while judges should be ready to

ignore the law on account of the principle of philanthropia l03. While compass

ion

for the penetes is advised, a judge is urged not to be influenced in his

decisions by the poor appearance of the litigant, for in the past he was a very

wealthy man 104. We should note here that only in a few passages in Psellos'

letters is justice defined in social terms (

) 105. According to another letter, the

qualities of the krites of Opsikion are the subject of a discussion between the

emperor and the krites' potential successors, the logothetes and Psellos: the

emperor wished that the krites remain in his position and he praised his

straightforward attitude 106.

Although judicial corruption is attested in the sources of all periods as a

serious problem of the Byzantine judiciary, it appears it became a serious

concern of the imperial administration in the 11th c: in a letter addressed to

the basilikoi notarioi Psellos enumerates their various duties, among which is

the handling of such cases107. In the same century John Mauropous describes

as corrupted the entire administrative system ( '

, , ...

) 108.

In the Peira there is reference to several cases of irregularities and corrup

tion

in the judicial system. We have already mentioned two cases in which

judges by using their authority forced penetes into illegal transactions for the

benefit of either the judge himself or a certain dynatos. In the title 51 on

judges ( ) other cases are mentioned. In the 51, 1 it is stressed that

it is against the law to entrust cases to judges who are related to one of the

litigants (in a family relationship, such as a father-son, or in a business rela

tionship,

such as owner-tenant). Such relationships would arouse suspicions of

100. Ibidem, p. 282; cf. also p. 298: ; . 184:

.

101. Psellos, Scripta minora, op. cit., 2, p. 83 11. 2-5, p. 100 1. 15, p. 128 1. 13, p. 191

1. 21, p. 192 11. 3-4, p. 193 11. 19-20, p. 262 11. 16-17; p. 90: ,

, , ,

, , .

102. Ibidem, . 47 11. 20-25: 6

.

103. Ibidem, p. 136 1. 24.

104. Ibidem, p. 100 11. 8 ff .

105. Ibidem, p. 297.

106. Psellos, Sathas, op. cit., p. 483: .

107. Ibidem, p. 486: . Cf. also Scripta minora,

op. cit., 1, p. 7 11. 23-26.

108. Johannis Euchaitorum metropolitae quae in codice valicano graeco 676 aupersunt,

d. P. de Lagarde, C.ttingen 1882. p. 170 (no 185).

188

HELEN SARADI

bias in judicial decisions 109. The section 16 of the same title deals with proce

dures in cases of disagreements between the judges: the decision of the major

ityof the judges of a court could be subject to an appeal which might correct

the abuse and the ignorance which resulted from that decision. It is inter

esting to note that in this text the ignorance of the judges is expressed with

two synonyms: , . The question of ignorance is very close to the

central concern of the age, that of legal education. The section 19 repeats the

Novel 45 of Leo VI that the judges should sign their decisions. The 51, 29

explains the reasons why a litigant can transfer his case to another judge: he

should be able to prove within eighteen days that the judge was either his

enemy (), or irascible (), or friend of his adversary110. The

section 32 cites the laws according to which the judges should apply the

existing laws in pronouncing their judgements, and they should neither

change them nor misinterpret them (Basil. 2, 1, 33; 29; 36).

Irregularities in court procedure are described in a proslagma of the emper

orManuel Komnenos of the year 1166. In the prooimion the role of the

emperor in securing justice is particularly stressed: he is .

topos that we have seen in earlier legislative texts, that of the divine origin of

justice, justifies the concern of the emperor about the problems of judicial

practice: "For if the righteous Lord loveth righteousness, it is doubtless fi

tting that he who has been chosen by Him to rule as emperor over those on

earth be righteous and, also, that he make right judgement a much desired

act of those put forward by him to sit in judgement and that he acknowledge

it (as such)" 1]1. The emperor gives an account of the social problems caused

by the judges' negligence: "... those appointed by My Majesty to the vindica

tion

of those who have been wronged should at least not be more negligent

() with regard to this than those who commit illegal acts. As it is,

(My Majesty) sees many men becoming wounded by a greedy and unjust

hand, enduring the loss of lands and dwellings and being deprived of other