Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Clinical Communications: Adults: A Living Will Misinterpreted As A DNR Order: Confusion Compromises Patient Care

Загружено:

queennita69Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Clinical Communications: Adults: A Living Will Misinterpreted As A DNR Order: Confusion Compromises Patient Care

Загружено:

queennita69Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

The Journal of Emergency Medicine, Vol. 40, No. 6, pp.

629 632, 2011

Copyright 2011 Elsevier Inc.

Printed in the USA. All rights reserved

0736-4679/$see front matter

doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2008.11.014

Clinical

Communications: Adults

A LIVING WILL MISINTERPRETED AS A DNR ORDER: CONFUSION

COMPROMISES PATIENT CARE

Antonios D. Katsetos,

DO

and Ferdinando L. Mirarchi,

DO, FAAEM

Department of Emergency Medicine, Hamot Medical Center, Erie, Pennsylvania

Reprint Address: Ferdinando L. Mirarchi, DO, FAAEM, Department of Emergency Medicine, Hamot Medical Center, 201 State Street Erie,

PA 16550

e AbstractBackground: Advance directives are becoming ever more commonplace in the United States. Correct

interpretation of living wills and do-not-resuscitate (DNR)

orders is essential if patient safety and autonomy are to be

preserved. Objectives: 1) To recount a case in which a living

will was misinterpreted as a DNR order; 2) To make known

the ramifications of this misinterpretation; 3) To advocate

for improved education of health care professionals regarding the interpretation and implementation of advance directives. Case Report: Mr. S. is an 89-year-old nursing

home resident who agreed to the terms of a living will. This

living will was subsequently misinterpreted as a DNR order

by the patients physician. This misinterpretation set off a

cascade of events that led to the completion of an out-ofhospital DNR order and a compromise of patient care.

Conclusion: This case study underscores the potential for

misunderstanding of an advance directive and the consequent

effect on patient care. Likely this is the result of a fundamental

lack of understanding about the terminology and definitions

inherent in an advance directive document. 2011 Elsevier

Inc.

wills and do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders is essential if

patient safety and autonomy are to be preserved. We

present a case in which a physicians misunderstanding

of a living will led to the eventual completion of an

out-of-hospital DNR order. This cascade of events and

lack of communication between physician and patient

led to a breach of patient autonomy and a compromise of

patient safety.

Details of our case have been altered to protect patient

confidentiality and the identity and location of the physicians and health care facilities involved.

CASE REPORT

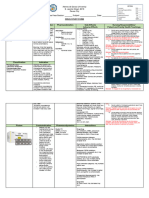

Mr. S. is an 89-year-old male nursing home resident

with a history of unilateral blindness, hypertension,

hearing loss, and remote bladder cancer (status postcystectomy 26 years ago) who presented to the Emergency Department (ED) with a 1-day history of slurred

speech and hypotension. The nursing home face sheet

indicated that the patient had an out-of hospital DNR

order and that Emergency Medical Services (EMS)

should not be activated (Figure 1). Therefore, he was

transported to the ED by private vehicle (facility van).

Included in the records sent by the nursing home was

a living will, in which the patient appointed a health

care proxy and indicated his wishes regarding medical

e Keywordsadvance directives; living wills; DNR orders; geriatrics; end-of-life care

INTRODUCTION

Advance directives are becoming more commonplace in

the United States. An estimated sixty million Americans

have a living will (1). Correct interpretation of living

RECEIVED: 15 February 2008; FINAL

ACCEPTED: 8 November 2008

SUBMISSION RECEIVED:

17 September 2008;

629

630

A. D. Katsetos and F. L. Mirarchi

evidence of any mood disorder. The patient explicitly

stated to the neuropsychologist, I know I am an old

man, but if the condition is treatable, I would like the

chance to be treated. The patient recovered to his baseline after further blood transfusions and upper endoscopy

(which was delayed until completion of the neuropsychological evaluation) and was discharged back to the

nursing home several days later.

DISCUSSION

Figure 1. A reproduction of Mr. Ss. nursing home face sheet

indicating that Mr. S. has an out-of-hospital DNR order and

that EMS should not be activated.

treatment should he be in a terminal condition or a

persistent vegetative state (Figure 2).

In the ED, the patient was found to be profoundly

anemic, hypotensive, and hypoxic. Although he was

visually impaired and hard of hearing, his mental status

and neurologic examination were otherwise normal. Mr.

S. was judged to be competent, and, though critical, his

condition was not judged to be terminal. Therefore, the

emergency physician judged the patients living will to

be inapplicable. The emergency physician had a discussion with the patient regarding his wishes for further

treatment. The patient stated that he wanted all necessary

treatment; as such, he was resuscitated, emergently transfused, and admitted to the intensive care unit. He was

later diagnosed with an acute gastrointestinal (GI) bleed.

While hospitalized, the patient reiterated to both his

attending physician and a consulting intensivist that he

wished to receive all necessary treatment. Both physicians indicated in dictated reports that the patient was

DNR and that he wished to reverse his code status. The

intensivist discussed code status at length with both the

patient and his daughter, who was designated as his

health care proxy and durable power of attorney. The

intensivist did not feel confident that the patient understood the implications of his decision to be a full code.

Therefore, he recommended a neuropsychological evaluation to assess the patients competence. The patient

received appropriate medical therapy for GI bleeding,

including packed red blood cell transfusions and proton

pump inhibitors while awaiting neuropsychological evaluation, which occurred the following day. The assessing

neuropsychologist found the patient to be competent to

make decisions regarding his code status and found no

Discussions with Mr. S.s family and review of nursing

home records revealed that he had, upon admission to the

nursing home, signed a living will as presented in Figure 2.

When questioned about the living will during the abovementioned neuropsychological evaluation, Mr. S. stated

that he signed the document because I had to. Mr. Ss

attending physician during a previous hospitalization reviewed the living will, and because it declined all lifesustaining measures, apparently misinterpreted it as a

DNR order. A DNR order was then entered into the

patients chart. To the best of our knowledge, this DNR

order was written without consultation with the patient or

his family. Upon returning to the nursing home from the

previous hospitalization, a case manager noted that

Mr. S. had a DNR order while hospitalized and arranged

for an out-of-hospital DNR order to be written by the

nursing home physician. This out-of-hospital DNR order

again was apparently written without discussion with the

patient or his family. As a result of the out-of-hospital

DNR order, EMS was not summoned when Mr. S. again

became ill, and, though unstable, he was transported to

the ED by nursing home staff in the facility van.

Mr. Ss case demonstrates that there is confusion

regarding the meaning and application of living wills and

DNR orders. Mr. S. had an effective living will at the

time of both hospital admissions discussed. An effective

living will is one that is valid and legally binding but that

has not been activated. In contrast, an enacted living will

is one that has been activated because the patients condition meets the terms of the living will (most often a

terminal condition or persistent vegetative state) (2). The

attending physician during the first hospital admission

misinterpreted Mr. Ss living will as a DNR order. This

error set off a cascade of events that resulted in Mr. S.

being denied EMS care despite being hemodynamically

unstable secondary to a GI bleed. Upon admission to the

hospital for GI bleed, both the admitting physician and

the consulting intensivist interpreted the patients acceptance of blood transfusions and other resuscitative measures as a reversal of his presumed DNR status. Although

a DNR order directs health care providers not to resuscitate a pulseless or apneic patient, it should not affect

Living Will Misinterpreted as DNR

631

Figure 2. A reproduction of Mr. S.s living will. Note that the patient has declined all interventions.

any other treatment decisions (3). EMS activation and

maximal therapy short of cardiopulmonary resuscitation are allowable for patients with DNR orders (4 9).

Therefore, regardless of Mr. S.s DNR status, EMS

activation and transfusion of blood products would

have been appropriate.

Misinterpretation of advance directives is an emerging and troubling problem (2). Recent surveys of physicians, nurses, and EMS providers demonstrated that a

significant percentage of providers at all levels interpreted a valid (but not enacted) living will as an order not

to resuscitate (2). Furthermore, survey results revealed

that DNR orders often are misconstrued as orders to

provide only comfort care (2). Several studies have

shown that patients with DNR orders are more likely to

have treatment withheld, even in non-terminal conditions;

such patients are less likely to receive aggressive nursing

care (4,10). Furthermore, nurses are less likely to notify

physicians of status changes in patients with DNR orders

(4). Such patients are also less likely to receive adequate

resuscitation and critical care interventions (11,12). In fact,

the appropriateness of Mr. S.s admission to the intensive

care unit was debated, initially, by the admitting physician

on the basis of the patients presumed DNR status.

Valid living wills do not equal DNR orders unless the

patient is in a terminal condition or persistent vegetative

state and the patient has indicated that he or she would

not want to be resuscitated if in such a state. Furthermore, DNR orders must not be misinterpreted as orders

not to treat conditions other than cardiac or respiratory

arrest. Staff misinterpretation of Mr. S.s out-of-hospital

DNR order led to his being denied EMS care despite

being critically ill. Re-wording of the nursing home face

sheet to read do not activate EMS in case of cardiac or

respiratory arrest might prevent a similar error in the

future.

Physicians spend little time discussing end-of-life issues with patients and their families. Tulsky et al. revealed that when the subject of advance directives was

broached, the conversation lasted 6 min, on average,

with the physician speaking two-thirds of the time (13).

Adequate communication between physicians, patients,

and family members is essential if patients wishes regarding end-of-life care are to be carried out appropriately. Lack of communication in both the hospital and

nursing home led to Mr. S. being made DNR without his

knowledge or consent. Similar cases of patients being

designated DNR without discussion or consent have

632

A. D. Katsetos and F. L. Mirarchi

been reported previously (14,15). Such a failure to communicate represents a disregard for patients autonomy and

potentially can lead to compromises in patient care and

safety.

CONCLUSION

The case presented demonstrates a lack of understanding

among several physicians and other health care providers

regarding the implementation, activation, and implications of advance directives. This lack of understanding

potentially compromises patient care, safety, and autonomy. At the very least, greater vigilance is needed to

understand the terms and conditions by which an advance directive becomes activated. Better understanding

is needed at all levels of care because each can adversely

affect subsequent decisions and efforts.

REFERENCES

1. US Census Bureau. 2004 Population estimates. Available at: www.

census.gov. Accessed March 2005.

2. Mirarchi FL, Hite LA, Cooney TE, Kisiel TM, Henry P. TRIAD I

The Realistic Interpretation of Advanced Directives. J Patient Saf

2008;4:235 40.

3. Presidents Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical Research. Deciding to forego life-sustaining

treatment. ethical, medical and legal issues in treatment decisions.

Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1983.

4. Henneman EA, Baird B, Bellamy PE, Faber LL, Oye RK. Effect of

do-not-resuscitate orders on the nursing care of critically ill patients. Am J Crit Care 1994;3:46772.

5. Bartholome WG. Do not resuscitate orders. Accepting responsibility. Arch Intern Med 1988;148:2345 6.

6. Guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiac care. Emergency Cardiac Care Committee and Subcommittees, American Heart Association. Part VIII. Ethical considerations

in resuscitation. JAMA 1992;268:2282 8.

7. Miles SH, Cranford R, Schultz AL. The do-not-resuscitate order in

a teaching hospital: considerations and a suggested policy. Ann

Intern Med 1982;96:660 4.

8. National Conference on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR)

and Emergency Cardiac Care (ECC). Standards and guidelines for

cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and emergency cardiac care

(ECC). Part VIII. Medicolegal considerations and recommendations. JAMA 1986;255:2979 84.

9. Sherman DA, Branum K. Critical care nurses perceptions of

appropriate care of the patient with orders not to resuscitate. Heart

Lung 1995;24:3219.

10. Beach MC, Morrison RS. The effect of do-not-resuscitate orders on

physician decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:2057 61.

11. Farber NJ, Simpson P, Salam T, Collier VU, Weiner J, Boyer EG.

Physicians decisions to withhold and withdraw life-sustaining

treatment. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:560 4.

12. Shelley SI, Zahorchak RM, Gambrill CD. Aggressiveness of nursing care for older patients and those with do-not-resuscitate orders.

Nurs Res 1987;36:157 62.

13. Tulsky JA, Fischer GS, Rose MR, Arnold RM. Opening the black

box: how do physicians communicate about advance directives?

Ann Intern Med 1998;129:4419.

14. Bedell SE, Delbanco TL. Choices about cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the hospital. When do physicians talk with patients?

N Engl J Med 1984;310:1089 93.

15. Mirarchi FL. Does a living will equal a DNR? Are living wills

compromising patient safety? J Emerg Med 2007;33:299 305.

Вам также может понравиться

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Chapter 004Документ6 страницChapter 004queennita69Оценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5795)

- Critical Thinking Activit2Документ8 страницCritical Thinking Activit2queennita69Оценок пока нет

- Documentation Charting and ReportingДокумент30 страницDocumentation Charting and Reportingqueennita69Оценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Chapter 007Документ3 страницыChapter 007queennita69Оценок пока нет

- Key Practice Problems N208Документ1 страницаKey Practice Problems N208queennita69Оценок пока нет

- Baird Decision ModelДокумент3 страницыBaird Decision Modelqueennita69Оценок пока нет

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Critical Thinking Activit1Документ2 страницыCritical Thinking Activit1queennita69Оценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Foundations of The TechnologyДокумент1 страницаFoundations of The Technologyqueennita69Оценок пока нет

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Nitko and Brookhart (2011)Документ1 страницаNitko and Brookhart (2011)queennita69Оценок пока нет

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Course Record AddendumДокумент1 страницаCourse Record Addendumqueennita69Оценок пока нет

- Diets For The NCLEXДокумент1 страницаDiets For The NCLEXqueennita69Оценок пока нет

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- Anaphylaxis and Epinephrine Auto-InjectorДокумент7 страницAnaphylaxis and Epinephrine Auto-Injectorqueennita69Оценок пока нет

- ACE Star ModelДокумент4 страницыACE Star Modelqueennita6950% (2)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Personal Academic Success Paper Rubric-3Документ4 страницыPersonal Academic Success Paper Rubric-3queennita69Оценок пока нет

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Undergraduate Nursing StudentsДокумент2 страницыUndergraduate Nursing Studentsqueennita69Оценок пока нет

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Acls DrugsДокумент1 страницаAcls Drugsqueennita69Оценок пока нет

- FlexRN Employee HandbookДокумент77 страницFlexRN Employee Handbookqueennita69Оценок пока нет

- Kimberly R. Bundley Helene Fuld School of Nursing Care PlanДокумент10 страницKimberly R. Bundley Helene Fuld School of Nursing Care Planqueennita69Оценок пока нет

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- End of Life Care: Cross Country University's Caregiver Safety SeriesДокумент2 страницыEnd of Life Care: Cross Country University's Caregiver Safety Seriesqueennita69Оценок пока нет

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- AccuChek Inform II CompetencyДокумент38 страницAccuChek Inform II Competencyqueennita69Оценок пока нет

- Disaster ManagementДокумент21 страницаDisaster ManagementLokesh Ravi TejaОценок пока нет

- Safety Data Sheet: Chevron (Malaysia) Unleaded GasolineДокумент12 страницSafety Data Sheet: Chevron (Malaysia) Unleaded GasolineaminОценок пока нет

- Contoh FMEA UIHC Burn Unit Patient Education DocumentationДокумент2 страницыContoh FMEA UIHC Burn Unit Patient Education DocumentationAnisaОценок пока нет

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- FDA Food Safety Modernization ActДокумент22 страницыFDA Food Safety Modernization Actfranzdiaz7314Оценок пока нет

- Risk Assessment - Working Ship SideДокумент3 страницыRisk Assessment - Working Ship SideSatya SatishОценок пока нет

- Background PF The StudyДокумент3 страницыBackground PF The StudyZT EstreraОценок пока нет

- A 6 Phlebitis and Infiltration ScalesДокумент1 страницаA 6 Phlebitis and Infiltration ScalesSorin Alexandru LucaОценок пока нет

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Oswestry Disability Index (ODI)Документ3 страницыOswestry Disability Index (ODI)Mohamed ZakiОценок пока нет

- A Novel Clinical Grading Scale To Guide The Management of Crusted ScabiesДокумент6 страницA Novel Clinical Grading Scale To Guide The Management of Crusted ScabiesFelisiana KasmanОценок пока нет

- The Purnell Model For Cultural CompetenceДокумент4 страницыThe Purnell Model For Cultural CompetenceLyra Lorca67% (3)

- Kelsey Resume 2024Документ1 страницаKelsey Resume 2024api-741147454Оценок пока нет

- LESSON 1 Occupational Health and Safety Policies and ProceduresДокумент11 страницLESSON 1 Occupational Health and Safety Policies and Procedurescky yarteОценок пока нет

- Cancer of Unknown PrimaryДокумент12 страницCancer of Unknown Primaryraul gutierrezОценок пока нет

- SMR August 19 (Rengat - Tembilahan, Sect 2) PDFДокумент28 страницSMR August 19 (Rengat - Tembilahan, Sect 2) PDFDoo PLTGUОценок пока нет

- PMFIAS CA 2019 05 12 SciДокумент107 страницPMFIAS CA 2019 05 12 SciShivy SwarnkarОценок пока нет

- Mentor Interview Questions TemplateДокумент3 страницыMentor Interview Questions Templateapi-381640393Оценок пока нет

- Abrasion Avulsion Incision Laceration Puncture: Wound TreatmentsДокумент10 страницAbrasion Avulsion Incision Laceration Puncture: Wound TreatmentsTheeBeeRose_07Оценок пока нет

- Air in The Urinary Tract: Images in Clinical MedicineДокумент1 страницаAir in The Urinary Tract: Images in Clinical MedicineSamira LizarmeОценок пока нет

- Renal Drug StudyДокумент3 страницыRenal Drug StudyRiva OlarteОценок пока нет

- Reduction of Perioperative Anxiety Using A Hand-Held Video Game DeviceДокумент7 страницReduction of Perioperative Anxiety Using A Hand-Held Video Game DeviceFiorel Loves EveryoneОценок пока нет

- Functional Motor AssessmentДокумент5 страницFunctional Motor AssessmentLoren EstefanОценок пока нет

- Kaleidoscope Therapy & Learning Center: Occupational Therapy Initial EvaluationДокумент7 страницKaleidoscope Therapy & Learning Center: Occupational Therapy Initial EvaluationJhudith De Julio BuhayОценок пока нет

- SOP-32-06 - Vendor Assessment (Oct 21)Документ11 страницSOP-32-06 - Vendor Assessment (Oct 21)parwana formuliОценок пока нет

- 1.2 Sample SDSДокумент7 страниц1.2 Sample SDSLaurier CarsonОценок пока нет

- Doctor's Appointment Portal: Project Report OnДокумент62 страницыDoctor's Appointment Portal: Project Report OnheamОценок пока нет

- ACOG Practice Bulletin No093 PDFДокумент11 страницACOG Practice Bulletin No093 PDFMarco DiestraОценок пока нет

- Concept Note Day of The African Child 2012Документ16 страницConcept Note Day of The African Child 2012Cridoc DocumentationОценок пока нет

- Clinical Asthma Pathway: ED Phase 1a: Initial Assessment - 1st HourДокумент2 страницыClinical Asthma Pathway: ED Phase 1a: Initial Assessment - 1st Hourd'Agung NugrohoОценок пока нет

- The Unhealthy Alliance: Crusaders For "Health Freedom"Документ16 страницThe Unhealthy Alliance: Crusaders For "Health Freedom"Nicolas MartinОценок пока нет

- q2 Grade 7 Health DLL Week 1Документ8 страницq2 Grade 7 Health DLL Week 1johann reyes0% (1)

- Alcoholics Anonymous, Fourth Edition: The official "Big Book" from Alcoholic AnonymousОт EverandAlcoholics Anonymous, Fourth Edition: The official "Big Book" from Alcoholic AnonymousРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (22)

- Healing Your Aloneness: Finding Love and Wholeness Through Your Inner ChildОт EverandHealing Your Aloneness: Finding Love and Wholeness Through Your Inner ChildРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (9)

- Save Me from Myself: How I Found God, Quit Korn, Kicked Drugs, and Lived to Tell My StoryОт EverandSave Me from Myself: How I Found God, Quit Korn, Kicked Drugs, and Lived to Tell My StoryОценок пока нет

- Allen Carr's Easy Way to Quit Vaping: Get Free from JUUL, IQOS, Disposables, Tanks or any other Nicotine ProductОт EverandAllen Carr's Easy Way to Quit Vaping: Get Free from JUUL, IQOS, Disposables, Tanks or any other Nicotine ProductРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (31)