Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Attachment Non Attachment

Загружено:

reinayo0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

81 просмотров8 страницEssay - ^FROM BOWLBY TO BUDDHA' - an

initial exploration of the meaning of

attachment and non-attachment and their

implication for Dramatherapy

by Di Gammage

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документEssay - ^FROM BOWLBY TO BUDDHA' - an

initial exploration of the meaning of

attachment and non-attachment and their

implication for Dramatherapy

by Di Gammage

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

81 просмотров8 страницAttachment Non Attachment

Загружено:

reinayoEssay - ^FROM BOWLBY TO BUDDHA' - an

initial exploration of the meaning of

attachment and non-attachment and their

implication for Dramatherapy

by Di Gammage

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 8

Dramatherapy Vol 28 No 2 Autumn 2006 'From Bowlby to Buddha'

^FROM BOWLBY TO BUDDHA' - an

initial exploration of the meaning of

attachment and non-attachment and their

implication for Dramatherapy

by Di Gammage

This Being Human

This being human is a guesthouse.

Every morning a new arrival.

A joy, a depression, a meanness,

Some momentary awareness comes

As an unexpected visitor.

Welcome and entertain them all!

Even if they're a crowd of sorrows,

Who violently sweep your house

Empty of its furniture

Still, treat each guest honourably.

He may be clearing you out

For some new delight.

The dark thought, the shame, the malice.

Meet them at the door laughing.

And invite them in.

Be grateful for whoever comes.

Because each has been sent

As a guide from beyond.

Rumi

Introduction

It is many years since my first encounter with Buddhism.

I vividly recall listening to a speaker, on a wet, windy

night, telling me that we are nothing, that an egoless state

is to be aspired to and that until we achieve this we will

continue to suffer. I was appalled and affronted! Here

was I working diligently to develop and shore up my own

ego (as well as the egos of my clients) only to be told

that letting go was the only way to alleviate suffering.

I experienced the speaker's words as threatening and

alien, and with anything experienced thus, I developed an

immediate aversion to it. As I reflect upon this encounter,

I wonder how other listeners heard him? My friend, for

instance, had not had such a violent reaction to his words

and frankly my rage baffled her. This event probably

contributed to the demise of our friendship.

Over the last three years I have found myself

responding more openly to the practice of Buddhism.

A curiosity has grown. I would like to believe that,

nowadays, there is generally more light and less heat in

my soul. I would like to think that my ability to respond

rather than react is deepening. Perhaps a seed was planted

that fateful evening all those years ago that has slowly

begun to germinate - 'The fruit of awareness is already

ripe, and the door can never be closed again' (Nhat Hanh,

1993: 59).

As a dramatherapist and play therapist and previously

a residential social worker, I have been exposed to and

witnessed much suffering. I consider the work I undertake

to be a privilege, and yet until fairly recently, my core as a

therapist has harboured an unease. Questions arose such

as: What is happening here? What is meant to happen?

How can I facilitate this happening? How will I know

when it does? To a more fundamental question: What do

I believe is the core of human existence - are we innately

'good' or innately 'bad'?

As I discover more about the practice of Buddhism,

the dharmic path, I am finding responses to my unease.

In particular, I have been intrigued by the subject of

Attachment. I have encountered both a resonance

and a discord with my existing knowledge of Western

psychology and Eastern philosophy around this concept.

Attachment theory proposed by John Bowlby and Mary

Ainsworth and the Buddha's teaching of non-attachment

seem to reflect and challenge one another and serve

to illuminate core understanding of what it means to

be human. What follows is, in effect, an enquiry into

the development of, and beyond, the ego - from the

incarnation of the child to an adult discovering some way

of moving beyond being a product of their conditioning.

I offer here my cautious exploration on the meaning of

attachment and non-attachment and its implications for

dramatherapy.

Who is the Buddha?

I have found that when Buddhists speak of Buddha,

there is often a reference to both the Buddha and to the

Buddha-nature within each of us. The Buddha, that is

the first Buddha, is Siddhartha Gautama, who was bom

a prince in India over 500 BC. Buddha was not a god.

Dramatherapy Vol 28 No 2 Autumn 2006 'From Bowlby to Buddha'

He was a human being and he suffered like any other

human being. Siddhartha abandoned his palatial lifestyle

at the age of 29 so that he might seek understanding of

the suffering he witnessed around him and search for

a way to end this suffering. Siddhartha wandered the

land for a period of six years, experimenting with many

practices which included over-indulgence, self-torture,

trance, yoga, deep discussion and ultimately, fasting. So

weakened and sick by the fasting, he famously sat down

under the bodhi tree declaring, 'I will not leave this place

until my understanding is complete...or I die' (de Bary,

1969; Nhat Hanh, 1998; Napthali, 2003). He remained

sitting there all night and when the morning star ascended

in the sky, he had an intense breakthrough. He became a

Buddha, filled with understanding and love. He became

enlightened. Henceforth, he vowed to do what he could

to relieve suffering in the world and for over forty years

this is what he did.

The word Buddha means quite simply 'awake' or

'awakened one'; in contact with an inner wisdom that

is inherent in everyone, which has been described as

'growing up - being completely at home in our world no

matter how difficult the situation' (Chodron, 1994: 139).

This principle resonates with the work of Carl Rogers,

and forms the basis of his person-centred approach to

psychotherapy. He believed that every human being

has an innate tendency towards trustworthiness. This

view is also shared by a great many psychotherapists and

psychoanalysts from differing backgrounds.

The Buddha's teaching is based upon the Four Noble

Truths. These Truths offer the individual a means of

embracing their suffering in order to look deeply into it.

The First Noble Truth is that suffering (dukkha) exists.

Buddha taught of the need to recognise and acknowledge

the presence of suffering, not to deny nor to minimise it.

The Second Noble Truth is the origin or arising of

suffering. A deep exploration into how this suffering

came to be. What is it we do, what is it we take in, that is

causing this suffering?

The Third Noble Truth is the ending of creating

suffering by refraining from doing what it is that causes

the suffering. Suffering can be transformed. Buddhism

is fundamentally a practice and it is the practice in ending

suffering. The Second and Third Noble Truths have great

significance for the therapist, for they unequivocally

convey the potential for healing by understanding

suffering.

The Fourth Noble Truth is the dharmic path that leads

to refraining from doing all that causes suffering and the

cultivation of what leads to happiness and liberation. The

path of transformation or core change.

Zen Buddhist and psychodramatist psychotherapist

David Brazier defines the Four Noble Truths as:

1) To accept the afflictions in this world as real.

2) To accept that associated with these afflictions are

energy and a motivating power that can be turned to

good or ill.

I 3) To harness that energy.

4) The noble life that results from so doing: a life

led by vision.

Brazier (2001:24)

The Four Noble truths are a kind of lens through which

we can look at our lives and which enable us to move

towards liberation. Although the Buddha believed

personal liberation to be the responsibility of the

individual, there is great onus upon community (sangha)

and the individual's dependency on others.

The Four Noble Truths are also a way of understanding

the process of therapeutic change; The personal growth

of the client is the client's own responsibility, however, it

is the therapeutic relationship that helps to facilitate this

growth. The challenge to the dramatherapist is in how

to harness the client's energy and facilitate its use for the

benefit of the client.

The Attachment Theory of John Bowlby and Mary

Ainsworth

In the late 1930s, British psychoanalyst John Bowlby

alerted the psychological world to the significance of

the relationship between a child's mental health and

developing character and the child's experience of their

mother's physical presence and her emotional attitude

towards her child. Prior to Bowlby's work (with the

notable exception of the Dorothy Burlingham and Anna

Freud's contributions (1944), 'any connection between

these, in the childcare professions, had been vague and

inconsistent, refiecting the prejudices of the era and the

professionals involved. Attachment theory is concerned

with understanding the nature of bonding established

between humans arising fundamentally from the need

for protection, safety and comfort. The human baby, in

contrast to other mammals, is bom woefully helpless and

is utterly dependent upon his caregivers for the early part

of life (I refer to the baby as male so as to distinguish

between him and his mother. I am, of course, also

referring to female babies).

Mary Ainsworth, colleague to Bowlby and a prominent

psychologist in her own right, furthered Bowlby's theory

by her meticulous documentation of her observations of

the mother-child relationship, (initially in Uganda, then

in the USA). It was Ainsworth who created the Strange

Situation Experiment. The Strange Situation Experiment,

one of the most widely-used and reliable psychological

diagnostic tools, enables professionals to ascertain the

pattern of bonding in the relationship established between

a mother and her child (Bowlby, 1988; Karen, 1994).

The significance of this first attachment is profound for

it provides the child with a blueprint that underscores

that individual's capacity to love and be loved and,

thus, all future relationships they will make, including

the relationship they will create with their own child

(Ainsworth & Wittig, 1969; Ainsworth, 1985; Ainsworth

etal, 1978; Main etal, 1985).

Dramatherapy Vol 28 No 2 Autumn 2006 'From Bowlby to Buddha'

The Strange Situation

In the experiment, the parent (usually mother though

fathers, also, take part in the experiment) and one year

old child are introduced to an unknown playroom and a

stranger in the role of experimenter. A one-way mirror

allows the situation to be observed. The baby's reactions,

responses and behaviour are noted when mother leaves

the room, during her absence and on her return. Of

particular importance to the observers are the ways

in which the baby separates from his mother, engages

with the experimenter during the mother's absence,

his willingness to be comforted by the experimenter,

his capacity to be alone and how he reunites with his

mother. When mother leaves the room a second time, the

experimenter departs also, leaving the baby alone. The

experimenter re-enters shortly afterwards, followed by

the mother. The experiment is concluded,

Ainsworth and her colleagues carefully observed and

recorded great numbers of mother-infant pairs and their

results were remarkably consistent despite wide variations

in background and experience. From these results the

researchers were able to categorise the behaviour patterns

of the children (Ainsworth et al, 1978). Ainsworth

identified three categories of attachment (a fourth was

created later). These categories are:

Secure Attachment

Secure attachment is characterised by the baby showing

some degree of distress at the mother's departure yet a

willingness to engage with the experimenter, to allow

himself to be comforted by the experimenter and to

show an interest in the toys. On his mother's return,

the securely-attached baby greets her with smiles,

chatter, crying or any combination of these. There is a

desire for physical comfort from the mother, and the

mother, securely-attached to her child, happily responds

to him. On mother's second exit accompanied by the

experimenter, the child's level of distress is intensified.

Reunion with mother involves the same responses shown

earlier only with greater magnitude.

This baby is confident that his mother is sensitively

responsive to him. He is trusting of his parent to be readily

available should he need her comfort and protection.

Insecure Attachment

Insecure attachment is sub-divided into three further

categories:

Anxious Resistant or Ambivalent Attachment

This baby is uncertain of his mother's availability or

sensitivity towards him. He cannot trust that she will

protect and/or comfort him when he is fearful or in pain.

This baby is always prone to separation anxiety, he is

clingy and untrusting of his environment and his own self

within it. Often, threats of abandonment are used by the

mother as a means of control. This mother is inconsistent

in her care of her baby, sometimes she is available and at

10

other times she is not.

In the Strange Situation, the ambivalently-attached

baby will show higher levels of distress than the securelyattached baby. He will be less willing to engage with

the experimenter, and less able to accept comfort from

the experimenter. On his mother's return, he will greet

her just as the securely-attached baby, however, the

ambivialently-resistant baby demonstrates an uncertainty

towards, his mother (reflecting his experience of her)

and this will manifest as simultaneously pushing his

mother away from him and a desire to be close to her.

Contradictory impulses may manifest as hitting, kicking,

or smacking at the same time as seeking comfort from

her.

Anxious Avoidant Attachment

Whereas the ambivalently-attached baby is uncertain

whether to trust his mother, the avoidantly-attached child

knows without doubt that he cannot trust his mother to be

available to him. He has learnt very early on that he is

unable to rely on her and therefore on his environment.

Ultimately, he has only himself and yet this self, borne out

of isolation and despair, is fragile and fragmented.

In the Strange Situation, the anxiously-attached baby

demonstrates a low level of distress on his mother's

departure. He is very familiar with this scenario and has

learnt to survive it as best he can. He seems detached from

his environment and, largely, from himself. His capacity

to play with the toys or engage with the experimenter is

severely hampered. This is a child who does not show his

distress because no one notices it anyway.

Disorganised Attachment

This third category of insecure attachment patterning was

included by Ainsworth and her colleagues as they noticed

a small, yet significant, number of children who did not

fit with either of the other categories as their behaviour

seemed disorientated and unpredictable. A child with a

disorganised attachment pattern is likely to demonstrate

similar characteristics as the ambivalently- or avoidantlyattached children, however, this child also engages in

stereotypic behaviour such as freezing and repetitive

movements like rocking or head banging.

In the Strange Situation the child with a disorganised

attachment pattern is likely to show extreme levels of

distress at his mother's departure counteracted by the selfcomforting behaviours identified above. His capacity to

play with toys or engage with the experimenter is grossly

impaired.

The Wider Context

In my view, it is absolutely crucial to include the other

parent (usually the father) in the child's attachment

patterning if this parent is present in the child's life. This

is not only for the reason that the father develops a separate

relationship with the child, which has the potential to be

as significant as that with the mother. It is important to

Dramatherapy Vol 28 No 2 Autumn 2006 'From Bowlby to Buddha'

include the other parent because the mother's availability

and her ability to respond sensitively to her child has a

direct inter-relationship with the father's capacity to be

available and sensitive to her. If the mother experiences

a secure attachment with her partner, she is more likely to

be able to offer this to her child.

The mother herself was once a baby and experienced

her first attachment with her own mother. As mentioned

above, all future relationships, including those made with

her own children, will have this first attachment as their

foundation.

It is not a foregone conclusion, however, that an

insecurely-attached individual will automatically go

on to create similar relationships in the future. Mary

Main, colleague of Mary Ainsworth, was forefront in

researching the longitudinal effects of infant attachment

patterns and their significance across the life cycle (Main,

1991). She determined that the insecurely-attached child

is still open to the possibility of secure attachments with

other people. In other words, transformation is possible.

One person who may become extremely significant

in the life of an insecurely-attached child or adult is the

therapist. Within the therapeutic relationship, that part of

the self, however small, that has remained inherently wise

and awaiting the opportunity to relate in a wholesome

way may be awakened and nurtured.

Enlightenment

Underneath the tree, the Buddha became enlightened.

Buddhism uses the concept of enlightenment to mean

ultimate realisation and liberation. Enlightenment is the

complete understanding of how we create suffering and

then living a life that is free from that suffering. Living a

life in love, freedom, openness and fearlessness.

Van Morrison urges me to 'Wake up' and tells me that

enlightenment is non-attachment (Van Morrison, 1990).

I asked my therapist what enlightenment means and

straightaway she said, 'It's living without fear'. Fear is to

mistrust or distrust. Therefore enlightenment must mean

to live with trust. To trust myself and the world I live in.

To realise my own trustworthiness. In real terms this

means - not to worry about money, my relationships, how

other people see me, what they think of me, my health,

the health and well-being of my children, my partner, my

family, my friends, my clients, the country, the world, the

lack of water, the amount of pollution, destruction of the

ozone-layer, exhaustion of the world's natural resources,

melting ice-caps, extinction of the polar bear, prostitution

of children, genocide, floods, insatiable human greed

and corruption, the lack of meaning in people's lives,

loneliness, violence, alcoholism and drug abuse, HIV,

poverty, children diagnosed with Attention Deficit

Hyperactivity Disorder, cancer, ageing, disease...death.

I understand there to be a difference between worry and

concern. It isn't that I lack concern for all the above,

what I am seeking rather, is a freedom from an unhelpful

self-obsession that refers only to me and to my ego. This

liberation allows a much more open, authentic concern for

all that is precious in life.

To live such an enlightened life? Who would refuse

this? So, in Buddhism, if enlightenment means to live

without fear, without suffering, and enlightenment is nonattachment, what does non-attachment mean?

Non-attachment

The whole of Buddhism has, at its core, the practice

of non-attachment, of letting go. Here, however, the

concept of attachment has meaning beyond relationships

with others. We can become attached to almost anything;

for example, our body (our beauty, our youth, our vigour,

our unsightliness, our limitations); our feelings ('I'm just

an angry person', 'I'm always anxious'); our beliefs ('I'm

right, you're wrong', 'There is only one way and that's

my way!'); the roles that we play in our lives (victim,

aggressor, martyr, rescuer, hero/heroine, carer, the wise

one); our material possessions, wealth and the illusion of

security that frequently accompanies these. Often implicit

in these attachments is a lack of choice, freedom and an

inability to change ('This is me...jealous/a perfectionist/

scared of commitment/unable to see the dirty dishes piled

up in the sink/withdrawn). When we cling so tightly to

something, we are closed to the possibility of anything

else.

There is a common belief that non-attachment implies

disconnection, aloofness or aversion to something. This

is an inaccurate belief. Avoidance of (moving away

from), ambivalence for (pushing towards and away

from) and clinging to (pushing towards) are all forms

of attachment (in the Buddhist sense of the concept) and

all involve suffering. There are resonances here with the

insecure-attachment patterns identified by Bowlby and

Ainsworth. Unlike the states of avoidance, ambivalence

and clinging, each of which has a foundation of fear and

a quality of closedness, non-attachment has a virtue of

heart and a quality of openness. It is possible to feel your

heart literally opening and closing when you are moved

or when you are feeling threatened or humiliated. This

experience is real and felt in the body.

Letting go is not the same as getting rid of, rather it is

about relaxing around, finding a spaciousness with, the

object or subject we are in relationship with.

Ego

Who or what is getting attached? Who am I? In the

Bowlby model, it is ego. Body-centred psychotherapist,

Ron Kurtz, originator of the Hakomi Method, maintains

that effort, an ego function, fundamentally obstructs the

healing process as it creates an 'I' and a something that

the 'I' wrestles with. In this struggle, a separate self is

created: an ego. When there is no struggle, effort fades

and ego loosens. It is this loosening of the ego that Kurtz

believes is essential for transformation. This relaxation

of the ego is not a passive giving up, but a giving in to

the process, a faith in something deeper in oneself. It is

11

Dramatherapy Voi 28 No 2 Autumn 2006 'From Bowlby to Buddha'

beyond the ego (Kurtz, 1990).

t h e suffering arises through the ego's attachment to

an object or subject, not so much the events in our lives as

the relationship we create to these events.

Co-arising

What if ego is so fragile and fragmented, how then can

it be let go of? A great many of the children I worked

with as a residential social worker, and some of my

dramatherapy and play therapy clients, I believe, have

extremely fragmented object relations. Surely, before one

can relinquish ego, one has to have had a good enough

sense of it?

Everyone has an ego. Sometimes, however, ego

is contracted and wounded and self crystallises into

something rigid and negative . Before an individual

is in any position to relinquish ego, ego needs to.be

strong enough and this can only be achieved through

the experience of secure attachment. The therapist can

become a crucial figure in the creation of this secure

attachment. In Buddhism, there is a concept called

co-arising, which means 'coming about together'.

Attachment is paradoxical in that one is simultaneously

connected to others and separate from them. This

paradox was familiar to psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott

as illustrated in his observation that we leam to tolerate

our aloneness through relationship with others (1971).

Secure attachment and non-attachment have the capacity

to be co-arising. As the client becomes more secure in

themselves, they simultaneously develop the capacity

to let go of themselves. Crystallised self loosens into

something much more fluid and responsive.

Once enough buoyancy of being has been reached,

when a secure-enough attachment has been created, then

client and therapist gradually begin exploring the client's

patterns of attachment; With compassion and nonjudgment they make the enquiry - who is getting attached

to what? The therapist encourages and supports the client

in their discovery, in developing a capacity for awareness,

in noticing what's happening in any given situation and

for living in the moment. The therapist helps the client to

notice whether the heart is tightening, or opening; whether

the breathing is shallow or deep and unobstructed. The

body is a delicate barometer for our emotional states and

the therapist can help the client become more attuned to

their physical self.

'The greater the degree of awareness, the less the

degree of grasping. It's psychological physics'

Levine (1994: 110)

As the Sufi poet Rumi advocates, the therapist reassures

the client in their welcoming of every emotional

state. Much can be leamt by inviting a sadness or

a despair to 'sit at the table' with one. Welcoming,

being a compassionate host and bidding farewell to any

emotional state is a powerful and liberating experience.

'I am feeling angei"' has a much more spacious quality

12

about it that 'I am angry'. 'There is anger' has even more

spaciousness as it is totally lacking in any reference to

self. The dramatherapist is naturally equipped with the

skills to facilitate the client in visualising, personifying

and conversing with emotions. Frequently in sessions,

my clients invite Frustration, Anger, Lust or another

emotion to a 'dinner party' so as to converse with their

guests. As dramatherapists we have an invaluable means

of supporting our clients in creatively connecting with

their suffering without threat of overwhelm.

Healthy attachments

Healthy attachments are simply those attachments that

do not cause or create suffering for the individual,

others or the environment. In Buddhism, terms such as

'wholesome' or 'unwholesome', 'helpful' or 'hindrance'

and more commonly used as opposed to dualist terms like

'good'or 'bad'.

'When the cause of suffering has been seen, healing is

possible'.

NhatHanh(1998:39)

With deepening awareness, the client learns to distinguish

the attachments that are healthy or harmful to their

wellbeing. When I think this, say that, act in this way,

my suffering increases. Very often our perceptions are

clouded by emotional states such as craving, anger,

ignorance and prejudice which cause great suffering.

Such emotional states are described as afflictions (the

seeds of which are the three kleshas - greed, hatred and

deep misunderstanding) in Buddhism. It is important to

facilitate the client in looking deeply at their perceptions

and to do this with kindness and compassion. It is when

the client knows the source of these unhealthy perceptions

that they will have a choice in whether to continue using

them or to explore alternatives. Authentic responsibility

(response-ability) arises from choice.

Choice and Empowerment

When the client is becoming more authentically

responsible, they are able to make more informed choices

in their life. What do you want/need and how can you

take responsibility for your part in creating this life? This

is a period of awakening joy and knowing when you are

experiencing it. Thich Nhat Hanh describes it as watering

the seeds of joy (1998). This is the cessation of suffering

and the presence of wellbeing. Pema Chodron identifies

the source of wisdom as whatever is going to happen to

you today and your response to this creating the future

(1994).

Current Western teaching in Buddhism

Within current Western teaching in Buddhism there seems

to be a wide range of ideas regarding non-attachment.

Some aspire to complete non-attachment to anything and

an egoless state. I realise now that the speaker cited in the

introduction was of this ilk. Whether he was right or not

Dramatherapy Vol 28 No 2 Autumn 2006 'From Bowlby to Buddha'

in his understanding of the dharmic path, I can't judge.

What I do know, however, was my aversive reaction to his

words which I experienced as violent and threatening.

I am fortunate to have encountered a more

compassionate interpretation of Buddhist concepts.

One that holds the position that to be noti-attached

does not automatically mean to throw something out.

It means having a healthy attachment to something that

does not cause or create suffering. Non-attachment in

dharmic practice is the building up of a reservoir of

love, compassion, clarity, wisdom and patience and to

be healthily attached to these. The Buddha had a healthy

attachment to meditation. He had a healthy attachmetit

to teaching. He even had a healthy attachment to being

the Buddha (Nhat Hanh, 1988). For myself, my journey

is to look at where and to what I am attached, and to

enquire with kindness and compassion whether these are

healthy attachments. This, I believe, is also the task of the

therapist.

Conclusion

As a naive and enthusiastic dramatherapist, I once

believed it was my place to affect change within my

clients. I was heavily influenced by many of the

environments in which I practised (mainly health and

education) where I was fully expected to direct my

clients in their healing process. Their 'healing' entailed

implementing a programme or action plan specifying

what the client needed to do and when they needed to

do it by. My credibility and my professional status as a

dramatherapist depended upon my success with clients,

and should my clients fail to co-operate with the 'master

plan' then they were seen as resistant and challenging.

Many inexperienced dramatherapists are subjected to

this covert (and sometimes overt) pressure within their

workplaces. They may also experience this from the

clients themselves, who are so used to handing the

responsibility for their wellbeing over to someone else

and, of course, when it does not work out, someone else

can always be blamed.

Buddhist psychotherapy is non-violent in its approach.

It offers the client an opportunity to change according to

their own innate wisdom and trustworthiness. It is not

about the therapist effecting change in the client, nor is

it about the therapist taking the credit for any change the

client does make. Any healing that happens is co-arising

between client and therapist.

I understand the therapist's task as one of helping

the client let go of those obstacles that are preventing

them grow and become all that they can become. Carl

Jung said patients do not get cured, they simply move

on (Kurtz, 1990). Irvin Yalom comments that the single

most valuable concept he learned as an inexperienced

psychotherapist was that all humans have an innate

propensity towards self-realisation (Homey, 1950). He

understood that the role of the therapist was therefore to

help the client identify and to let go of those obstacles that

have thus far served to restrict the client's psychological

growth (Yalom, 2001). Ron Kurtz stresses, 'This is very

special work. In this process, violence is not only useless,

it is inevitably harmful' (Kurtz, 1990: 6).

Over the years of practice I have become increasingly

aware of a disquiet within myself. At times this disquiet

has manifested as an out-and-out rebellion. Yet when I

tried to give voice to my uneasiness, it was generally met

with blank expressions and something along the lines of,

'Well, that's just how it is'. Rare, precious, encounters

with some more enlightened beings persuaded mie that it

did not have to be this way. It seems it is never too late

to accommodate alternative ways of meeting the world.

Their trust in me and my capabilities encourages me

to believe in myself, and this quality of the therapist is

crucial if she is to authentically convey to her clients that

she believes in them and their own capacity for healing

and growth.

Buddhism teaches that life is constantly changing

in a dynamic way dependent on both internal and

external processes and conditions. It has much to

offer dramatherapy, and dramatherapy lends itself very

generously to the exploration and transformation of the

client's attachment patterns; obstacles which may have

served some function at some time but now prevent the

client from growth and self-realisation.

As a Buddhist dramatherapist my intention is to

create and maintain an unconditional acceptance of my

client based on Buddhist confemplative practice. The

deep respect I have for my client, for their innate wisdom

and their ability to work with the organisation of their

own experience is encapsulated in the Rumi poem, 'This

Being Human'. Together, we create the conditions that

allow the client to harness their energy and to effect core

change in their life.

References

Ainsworth, M. & Wittig, B. (1969) 'Attachment and

exploratory behaviour of one-year-olds in a strange

situation' in B.M. Foss (ed) Determinants of infant

behaviour, vol. 4, London: Methuen.

Ainsworth, M., Blehar, M., Waters, E., and Wall, s. (1978)

Patterns of attachment: assessed in the strange situation

and at home, Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Ainsworth, M. (1982) 'II Attachments across the lifespan'. Bulletin of New York Academy of Medicine, 61:

791-812.

Bowlby, J. (1988) A Secure Base - Clinical applications

of attachment theory London: Routledge.

Brazier, D. (2001) The New Buddhism -A Rough Guide

to a New Way of Life London: Robinson.

13

Dramatherapy Vol 28 No 2 Autumn 2006 'From Bowlby to Buddha'

Burlingham,D. and Freud, A. (1944) Infants without

families London: Allen and Unwin.

Chodron, P. (1994) Start Where You Are At-How to accept

yourself and others London: Harper Collins

Homey, K. ( 1950) Neurosis and Human Growth New

York: W.W.Norton

Karen, R. (1994) Becoming Attached - First Relationships

and how they Shape our Capacity to Love Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Kurtz, R. (1990) Body-Centred Psychotherapy - The

Hakomi Method CA: LifeRhythm.

Levine, S. (1979) A Gradual Awakening- A Guide to

Greater Awakening Dublin: Gateway.

Morrison, V. (1990) Enlightenment from the Album

'Enlightenment' Caledonia productions Ltd.

Napthali, S. (2003) Buddhism for Mothers NSW,

Australia: Allen & Unwin.

Nhat Hanh, T. (1988) The Heart of Understanding

Berkeley: Parallax Press

Nhat Hanh, T. (1993) Call Me By My True Names: The

Collected Poems ofThich Nhat Hanh Berkeley: Parallax

Press.

Nhat Hanh, T. (1998) The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching

- Transforming suffering into peace, joy and liberation

London: Rider.

Rumi (1995) Selected Poems - translated by Coleman

Banks London: Penguin.

Winnicott, D. (1971) Playing and Reality London:

Tavistock.

Yalom,I. (2001) The Gift of Therapy London: Piatkus

14

Вам также может понравиться

- Seeing The Mind, Stopping The Mind, The Art of Bill Viola: Jamie JewettДокумент15 страницSeeing The Mind, Stopping The Mind, The Art of Bill Viola: Jamie JewettreinayoОценок пока нет

- Screenplay1 627873Документ134 страницыScreenplay1 627873spasticfuckhead54Оценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (890)

- The Virtuous Burglar - Dario FoДокумент37 страницThe Virtuous Burglar - Dario Foreinayo100% (5)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Drama & Mental IllnessДокумент12 страницDrama & Mental IllnessreinayoОценок пока нет

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- Acting Transcendent Dimension.M ChekhovДокумент6 страницActing Transcendent Dimension.M Chekhovreinayo100% (1)

- Fallin Off A WallДокумент13 страницFallin Off A WallreinayoОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Theory of Everything ScreenplayДокумент95 страницThe Theory of Everything Screenplayspasticfuckhead5450% (2)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Chekhov&ImaginationДокумент14 страницChekhov&Imaginationreinayo100% (1)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Concept of Health and IllnessДокумент24 страницыConcept of Health and IllnessHydra Olivar - Pantilgan100% (1)

- Reglas para Añadir Al Verbo Principal: Am Is Are ReadДокумент8 страницReglas para Añadir Al Verbo Principal: Am Is Are ReadBrandon Sneider Garcia AriasОценок пока нет

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Forensic Science Project Group B5518Документ5 страницForensic Science Project Group B5518Anchit JassalОценок пока нет

- ZCT ZCT ZCT ZCT: 40S 60S 80S 120S 210SДокумент1 страницаZCT ZCT ZCT ZCT: 40S 60S 80S 120S 210SWilliam TanОценок пока нет

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Proforma For Iphs Facility Survey of SCДокумент6 страницProforma For Iphs Facility Survey of SCSandip PatilОценок пока нет

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Clarifying Questions on the CPRДокумент20 страницClarifying Questions on the CPRmingulОценок пока нет

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- Apraxia of Speech and Grammatical Language Impairment in Children With Autism Procedural Deficit HypothesisДокумент6 страницApraxia of Speech and Grammatical Language Impairment in Children With Autism Procedural Deficit HypothesisEditor IJTSRDОценок пока нет

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

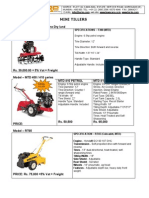

- Optimize soil preparation with a versatile mini tillerДокумент2 страницыOptimize soil preparation with a versatile mini tillerRickson Viahul Rayan C100% (1)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Primary Healthcare Centre Literature StudyДокумент32 страницыPrimary Healthcare Centre Literature StudyRohini Pradhan67% (6)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- Step by Step To The Perfect PedicureДокумент6 страницStep by Step To The Perfect PedicurepinkyОценок пока нет

- Palm Avenue ApartmentsДокумент6 страницPalm Avenue Apartmentsassistant_sccОценок пока нет

- ESD Control Experts: Electrical Overstress (EOS) and Electrostatic Discharge (ESD) EventДокумент39 страницESD Control Experts: Electrical Overstress (EOS) and Electrostatic Discharge (ESD) EventDaiana SilvaОценок пока нет

- Adapted Sports & Recreation 2015: The FCPS Parent Resource CenterДокумент31 страницаAdapted Sports & Recreation 2015: The FCPS Parent Resource CenterkirthanasriОценок пока нет

- Strain Gauge Load Cells LPB0005IДокумент2 страницыStrain Gauge Load Cells LPB0005ILordbyron23Оценок пока нет

- Technical PaperДокумент10 страницTechnical Paperalfosoa5505Оценок пока нет

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Case Study - BronchopneumoniaДокумент45 страницCase Study - Bronchopneumoniazeverino castillo91% (33)

- LAOKEN Comparison With J&JДокумент3 страницыLAOKEN Comparison With J&JMario Alfonso MartinezОценок пока нет

- Biochips Combine A Triad of Micro-Electro-Mechanical, Biochemical, and Photonic TechnologiesДокумент5 страницBiochips Combine A Triad of Micro-Electro-Mechanical, Biochemical, and Photonic TechnologiesDinesh KumarОценок пока нет

- 1.4 Market FailureДокумент42 страницы1.4 Market FailureRuban PaulОценок пока нет

- Finding the Right Pharmacy for Your NeedsДокумент4 страницыFinding the Right Pharmacy for Your Needsprabakar VОценок пока нет

- Physiology of Women Reproduction SystemДокумент52 страницыPhysiology of Women Reproduction Systemram kumarОценок пока нет

- LENZE E84AVxCx - 8400 StateLine-HighLine-TopLine 0.25-45kW - v9-0 - ENДокумент291 страницаLENZE E84AVxCx - 8400 StateLine-HighLine-TopLine 0.25-45kW - v9-0 - ENClaudioОценок пока нет

- Badhabits 2022Документ53 страницыBadhabits 2022Sajad KhaldounОценок пока нет

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Kuratif RacunДокумент18 страницKuratif RacunYsrwncyОценок пока нет

- HVDCProjectsListingMarch2012 ExistingДокумент2 страницыHVDCProjectsListingMarch2012 ExistingHARLEY SANDERSОценок пока нет

- Effective Determinantsof Consumer Buying Decisionon OTCДокумент13 страницEffective Determinantsof Consumer Buying Decisionon OTCThinh PhamОценок пока нет

- Cloudsoc For Amazon Web Services Solution Overview enДокумент6 страницCloudsoc For Amazon Web Services Solution Overview enmanishОценок пока нет

- BOM Eligibility CriterionДокумент5 страницBOM Eligibility CriterionDisara WulandariОценок пока нет

- Idioma Extranjero I R5Документ4 страницыIdioma Extranjero I R5EDWARD ASAEL SANTIAGO BENITEZОценок пока нет

- Deped Memo No. 165, S 2010: WastedДокумент6 страницDeped Memo No. 165, S 2010: WastedJayne InoferioОценок пока нет