Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Jane Austen Now With Ultraviolent Zombie Mayhem

Загружено:

Leo MercuriОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Jane Austen Now With Ultraviolent Zombie Mayhem

Загружено:

Leo MercuriАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

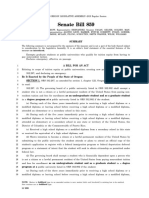

Adaptation Vol. 6, No. 3, pp.

338354

doi:10.1093/adaptation/apt014

Advance Access publication 25 July 2013

Jane Austen Now with Ultraviolent

ZombieMayhem

CAMILLANELSON*

Seth Grahame-Smiths Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, and Steve Hockensmiths Dawn of the

Dreadfuls and Dreadfully Ever After. It considers the proliferation of these differently adapted texts

across a range of platforms in the context of a converging and market driven media landscape,

including associated book trailers, an interactive eBook, a video game, and media reviews. It

argues that the texts signal, configure, and perhaps even mask contemporary fears and anxieties

over class and race, and the social processes of commodification under capitalism.

Keywords Pride and Prejudice, zombies, Jane Austen, mash-ups, adaptation theory.

England, 1813, a once green and pleasant land is beset by a plague of the living dead.

In a quiet country village, corpses dig their way out of graves. Crypt doors burst open.

The churchyard becomes a breeding ground for an army of Satans soldiers. Hordes

of shambling, soulless, brain-devouring monsters rampage unchecked across the green

and pleasant fieldsupturning coaches, and invading the houses of the rich. The

zombie herd may be terrifying, but the horror it inspires is nothing compared to the

threat of contagion. Amere scratch from a zombie is enough to transform a feeling,

sentient being into a rapacious, brainless, ghoul destined to multiply the armies of the

undead

This is the plotline of one of the most recent adaptations of Jane Austens Pride

and Prejudice (1813)a trilogy that includes Seth Grahame-Smiths mash up Pride and

Prejudice and Zombies, and Steve Hockensmiths Dawn of the Dreadfuls and Dreadfully Ever

After. The trilogy has been billed as a comedyindeed, it has been regularly castigated as a trite and meaningless frivolitybut it is also one of the more interesting

examples of what David McNally has called the capitalist grotesque (2). It effortlessly

blends regency comedy of manners and twentieth-century soap with elements appropriated from digital fan cultures and the genre of monster tales that for critics such as

Franco Moretti have traditionally signalled the presence of popular social anxieties

over the processes of commodification under capitalism. In the Jane Austen trilogy

published by Quirk, the mysterious zombie plague that terrorizes the good citizens of

Hertfordshire seems at once to map the unseen social forces hovering at the edges of

what Mary Poovey has called Jane Austens non-referential aesthetic (251), but also,

*Department of Communications, School of Arts and Sciences, University of Notre Dame, Australia.

E-mail: Camilla.Nelson@nd.edu.au.

The Author 2013. Published by Oxford University Press.

All rights reserved. For permissions, please email: journals.permissions@oup.com

338

Downloaded from http://adaptation.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Sydney on July 9, 2014

AbstractThis essay examines the Pride and Prejudice and Zombies phenomenon, including

Jane Austen Now with Ultraviolent Zombie Mayhem 339

in an interesting variety of ways, symbolically acts out social fears about the monstrous

dislocations at the heart of contemporary existence.

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies

Downloaded from http://adaptation.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Sydney on July 9, 2014

Grahame-Smiths Pride and Prejudice and Zombies is a mash-up of Jane Austens classic

text, promoted by its author as 85% Austen and 15% Grahame-Smiththe 15% comprising the maraudings of the undead and the Bennett sisters fighting back with their

death-dealing katanas. The most notable feature of the runaway bestseller is the way in

which it appropriates elements and techniques of amateur creativity more commonly

associated with digital networks of fansthe amateur-made mixes and mash-ups that

populate You Tube, for example, or the alternate universe and slash scenarios that

populate websites devoted to fanfiction. However, unlike the most pervasive form of

mashupvideo mashups such as Becoming Hermione or Superwholock, to name a couple of

recent examplesPride and Prejudice and Zombies is an industry made text, one of a series

of books commissioned by Jason Rekulak, the editor of Quirk. Indeed, the oft-repeated

impetus for the book was avowedly industrial. Rekulak told interviewers at the time of

the books launch that he had developed a list of popular fanboy characters like ninjas,

pirates, zombies, and monkeys with a list of public domain book titles (that is, books no

longer in copyright that can be published for free) (Rekulak, in Anderson). GrahameSmith was commissioned to begin with the original Austen text, and in the manner of a

video mashup to weave the zombie and ninja elements into the existing plotline.

Indeed, Pride and Prejudice and Zombies is one in a recent spate of industry-made texts

that have moved to appropriate elements of fan culture. The successful BBC series Lost

in Austen, for example, in which a fan finds herself transported into the events of what is

indisputably Jane Austens most famous novel, also presents itself as a kind of industrymade fanwork, including a metacommentary on the popular 1995 BBC television series

starring Colin Firth. More recently, the cocreators of Sherlock Michael Gatiss and Steve

Moffat announced at the Edinburgh Television Festival that the BBCs Sherlock was

just a giant piece of amateur enthusiasm. We love Sherlock Homes so muchwere

obsessed with it. This is fanfiction (Gatiss, in Frost). However, unlike these other industry-made fan products, Grahame-Smiths adaptationinitially, at leastpositioned

itself in opposition to other industrial productions that implicitly or explicitly claimed

a respectful relationship to the text, even when it is a subversive-yet-utterly-respectful

relationship, to quote from Teemans review of Lost in Austen in the Times. Pride and

Prejudice and Zombies was originally promoted as the work of an anti-fan. It originally

positioned itself as a form of populist rebellion against the oppressive cultural authority

of Jane Austens work, particularly as this cultural authority is evinced in the classroom

and the lecture hall. The mock discussion questions that appear at the end of the text

satirize the pedagogical practices of book clubs, librarians, and high school teachers. As

the promotional blurb on the back-of-the-book puts it, this is a work that transforms a

masterpiece of world literature into something youd actually want to read.

This aspect of the text was highlighted in the first Pride and Prejudice and Zombies book

trailer, a mashup combining the BBC production of Pride and Prejudice with George

Romeros Night of the Living Dead, rendered with the kind of twenty dollars and four

pizzas aesthetic that is typical of amateur-made fanworks. Does Dialogue like

340 CAMILLA NELSON

Downloaded from http://adaptation.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Sydney on July 9, 2014

This Make You Want to Gouge Your Eyes out with Boredom? the title text asks

the viewer. The trailer then cuts to an exchange between Jane Bennet and Mr Collins

in which Jane asks him to explicate a passage from Fordyces sermons that she believes

to be of great doctrinal import. In Austens novel, Fordyce functions as an element

of the books layered satire. Fordyce was an eighteenth-century cleric and author of a

book of sermons designed to warn young women against the moral dangers of reading

popular novels. In the featured BBC scene, Janes real object is to remove Mr Collins

from the proximity of Elizabeth. The book trailer, with its own set of ironies, helpfully

suggests, Maybe You Need Some Zombies. The sound shifts abruptly to a speed metal

tracknamely, Ministrys Jesus Built My Hotrodas the trailer promises gut-eating

zombies, kick-arse sisters, ninjas, swordfights and zombie mayhem. Ironically,

the trailer also offers to supplement this with a bit of refinement. This refinement is

presented as a pastiche of the cover lines that commonly appear on the back of more

orthodox editions of Austen, namely a timeless tale of first impressions and social

classin Regency England.

Romeros Night of the Living Dead, which dominates the second half of the book trailer,

is the paradigmatic zombie film and an obvious touchstone for Grahame-Smiths mash

up of Austen. In this classic of 1960s cult cinema, Romero and cowriter John Russo

are commonly credited with introducing the zombie apocalypse to western culture,

effectively transforming the zombie or soulless slave of Haitian Voodoo folklore into a

flesh-eating ghoul. Night of the Living Dead was the inspiration for five sequels and two

remakes, as well as an ever-expanding crowd of associated films and stories. These films

have long-functioned as objects of critical fascination, and are commonly understood to

express anxieties over a range of domestic threats, civil rights, violence arising from the

war in Vietnam, as critiques of contemporary consumerism or the military-industrial

complex. In more recent times, there appears to have been a further transformation of

the zombie figure, seen, for example, in the sharply vicious nature of the living corpses

in 28 Days Later, or in the Romero remake Dawn of the Dead, which is conspicuous for the

way it substitutes fast-moving corpses for the slow shamblers of classic Romero. Indeed,

the zombies that feature in the Quirk trilogy are polite by these standards. They are

not the harmless slap-stick zombies played for belly laughs that feature in what seems

to be an emerging subgenre of zombie comedies such as Shawn of the Dead. They are

old-fashioned zombies that single a return to the monsters that populate the earlier

films. There are, in the Quirk trilogy, for example, few pre-emptive strikes against contaminated humans and few pre-emptive executions (though there is a memorable one

outside the gates of fortified London in the final book). The emphasis inevitably falls on

polite amputations or honorable suicides carried out by the victims, which are ironically

evoked as being in the best English tradition.

Indeed, the Quirk trilogy is notable for the way it breaks many of the conventions of

the zombie genre. Rarely, for example, do zombie narratives feature period or futuristic

settings. Zombie films are more commonly set in the present and generally address

contemporary fears and anxieties. As well, zombie films are for the most part set in

claustrophobic city landscapes, showing zombies invading shopping centres and apartment blocks, whereas the Quirk trilogy features a rustic well-mannered social setting

at least, until the final book of the trilogy in which much of the action is set amidst the

Jane Austen Now with Ultraviolent Zombie Mayhem 341

Downloaded from http://adaptation.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Sydney on July 9, 2014

dangerous and polluted spaces of nineteenth-century London. Zombie narratives also

rarely feature happy endings. They are one of the few mainstream genres that regularly

adhere to the convention of the nihilistic ending. The typical zombie narrative features

a social order in tatters, with a small group of survivors, who, for the duration of the

film, at least, gain a brief respite from the pervading terror. Even though a handful of

the characters survive through to the end of the film, the implication in the conventional zombie film is that the survivors will not in fact survive for long. This makes the

Quirk trilogy different, for the books feature three decidedly happy endings in arow.

In early 2009, awareness of the forthcoming release of Pride and Prejudice and Zombies

started to rise mostly due to Internet bloggers. Newspaper articles followed. In response,

Rekulak increased the initial print run from 12,000 to 60,000 copies. On April 9, 2009,

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies moved from 300 to 27 on Amazon UKs bestseller list,

moving to number three on the New York Times bestseller list the same day. At the elite

end of the market, responding to Rekulaks promise of readability, perhaps, the hackles

of some commentators rose. The New Yorkers Macy Halford called the prose style of

the book one hundred per cent terrible. Grahame-Smith told the Sunday Times that

he had faced the wrath of Austen fans on blogs and certainly there were a number of blog posts on Austen fan sites that started, Purists will hate this book or

Purists will vomit . However, as the Sunday Times pointed out, despite the apparently

oppositional stance adopted by the publicists, Austen fans are loving this unholy romp

(Goodwin). Grahame-Smith was soon to be found telling audiences at bookshop signings that they ought to be reading the original Austen. The death knell finally sounded

for the texts antifan position with the release of the interactive version of Pride and

Prejudice and Zombies for iPads and other tablet devices. In this version of the text, the

Grahame-Smith adaptation appears directly beside the original Austen novelpage

for page. Rekulak states that the eBook was published in response to requests from

readers, and an iPad allows you to compare the two texts side-by-side very effectively.

Indeed, the trailer designed to coincide with the eBooks release advises the reader that

it is in fact far preferable to Read Pride and Prejudice and Zombies alongside Jane

Austens original text.

It may be that this shift in the paratextual frame was simply a question of marketing, predicated on a belated realization that Our Jane and her gigantic fandom are of

course highly saleable commodities. But the reversal also draws attention to the diverse

ways in which the cultural values attached to Austens work are constantly being altered

by the commercial demands of the media industry, which, in its innumerable adaptations, is not only rewriting Austen but continually rewriting the modernist conceptual

divide between high and low art. The idea of the literary cannon and canonicity,

for example, appears to have found a new function in the market-driven economy of

the media, becoming one in a wider range of technologies for branding and consumption. In this shifting media landscape, Austen is no longer an author, but what Henry

Jenkins would call a story franchise, and Pride and Prejudice and Zombies is just one of

the more recent outgrowths from this larger shifting structure. Hence, the assault on

canonical prejudice that Pride and Prejudice and Zombies initially envisaged was an assault

on a hierarchical cultural formation that the media industry had already redrawn.

Moreover, this redrawing should not be understood as a collapse in traditional regimes

342 CAMILLA NELSON

Downloaded from http://adaptation.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Sydney on July 9, 2014

of cultural value, but as part of an ongoing process of cultural negotiation. Regimes of

value are a product of social relations and arrangements of knowledge, as John Frow

has influentially argued, but in a market driven economy the production of cultural

objects will also be governed by a shifting and sometimes anomalous perception about

what will appeal to the greatest segment of the market as possible. Rekulak confirmed,

I expected hate mail, but the response of Austen fans was a delightful surprise. He

went on to argue that despite the obvious satirical content of the novel, Seth is not

making fun of Pride and Prejudice. He understands that generations of readers love this

book. He knew it would be crazy to make fun of it. He also reaffirmed the cultural

status of the Austen brand. Its such a landmark and important novel.

On another level, the shift in the texts market position also sheds light on the long

discussed problem of fidelity discourse in adaptation studies. This movement beyond

fidelity discourse was originally pioneered by critics such as Deborah Cartmell, Imelda

Whelehan, and Robert Stam. Recently, Thomas Leitch has progressed the argument

further, stating that critics should not limit themselves to a single literary source,

but should have regard to a wider range of works in an intertextual field. Costas

Constandines has taken up a similar position, arguing that critics must take into consideration other media texts or subtexts that share familiar characters and narratives

(2). Jenkins and Thorburn have also argued with respect to media analysis more generally that critics must resist notions of media purity, recognizing that each medium

is touched by and in turn touches its neighbours and rivals (11). In short, whether or

not the relationship between adaptations and perceived originals ought to be construed

horizontally (rather than hierarchically) as Linda Hutcheon argues, in terms of the

actual cultural practices of readers, adaptations are certainly texts that demand to be

read relationally. Adaptations are texts that are radiant with the traces of other texts,

and the flaunting of traces is often used to affirm the texts status as an adaptation.

The traces have the effect of highlighting distance, producing gaps in which the possibilities of the text begin to proliferate, uncontrollably at times, especially for a reader

who is literate in the discourses and genres that the adaptation inhabits. In negotiating

such a text, the reader oscillates not only between the text and its perceived originals,

but also between the text and its adaptations across an intertextual field of difference.

In this sense, despite its joyful pillaging of Austens words, Grahame-Smiths Pride and

Prejudice and Zombies mash up might be said to refer as much, if not more to the 1995

BBC adaptation, and to countless other adaptations, than it refers to the original or

historical Austen.

The complexity, and indeed, flexibility, of the processes of reading an adaptation,

can be registered in the ease with which diverse audiencesincluding, scholars, bloggers and fanswere able to reconcile Our Jane with a rampaging herd of zombies.

The same blog posts that claimed Purists will hate this book also went on to explain

why the blogger was not a so called Purist, arguing that far from rolling over in her

proverbial grave Our Jane would surely have appreciated the joke (indeed, in the early

nineteenth century the relationship between high and low culture was far less rigid).

Even Halford in the New Yorker, while decrying the lugubriousness of the prose style,

immediately went on to invoke the work of a respected Austen scholar who argued that

the Grahame-Smith mashup had accurately identified a subtextual theme of mystery

Jane Austen Now with Ultraviolent Zombie Mayhem 343

Downloaded from http://adaptation.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Sydney on July 9, 2014

and menace in the original book. Her novels are hostile environments, another Austen

scholar told reporters (Goodwin).

Hostility has indeed been the focus of much recent work by Austen scholars, who

have begun mining the uncomfortable and even violent sides to Austens texts to great

effect. William Galperin has drawn attention to the ways in which Austens light, bright

and sparkling world is also a dark, multilayered and complicated reality. He argues that

although the plot interest in Pride and Prejudice centres on Darcyor more explicitly, on

the desire for Darcythere are many elements that appear not always consistent with

this orientation and the ideological function that it performs (25). Claudia Johnson has

also argued for a subversive agency in Austens writing. Property, marriage and family

are dark and hostile institutions in Austen, according to Johnson, and although Pride and

Prejudice is often seen to represent some kind of failure of nerve (74)evading questions about the fate of educated women in a patriarchal society, or suggesting that the

existing state of society sustains rather than destroys real happinessJohnson argues

that to imagine versions of authority responsive to criticism and capable of transformation is not necessarily to corroborate conservative myths(74).

However, any appeal to the historical Austen as a means of uncovering meaning in

Grahame-Smiths text is fraught with problems. It must be clearly balanced against an

understanding that this is a text that is made and mobilized in the context of twentyfirst-century American society. The mysterious plague that the text envisions has less to

do with the middleclassviolence that the historical Austen does or does not depict, but

is ratheror so this essay will attempt to arguea symptomatic representation of the

violence of the American Empiretoday.

In short, Austens text has been adapted to an altogether different purpose. Austens

novel was well suited for such adaptive re-use, according to Grahame-Smith, precisely because so many parts of the story are mysteriously missing. Theres this militia

camped near Meryton. They are there for the young Bennet girls to flirt with, but apart

from that, what are they doing there? Its never really explained (Grahame-Smith, in

Goodwin). This is what Mary Pooveyin more formal academic prosehas called

Austens nonreferential aesthetic. The British militias are a frequent feature of Austens

work, but they do not appear in any political sense. They appear purely in relation to

the romantic plot. Poovey applies this idea to many aspects of social life and politics

as they are represented in Austens work. Famously, Austens life spanned the dramatic

social upheavals of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuriesthe American

War of Independence, the French Revolution, the Reign of Terror and the Napoleonic

Wars, but none of these upheavals feature as threats or otherwise in her fictional world.

Pride and Prejudice was written at a time when the enclosure acts were steadily driving

the rural working classes off the land into urban areas, which were rapidly undergoing industrialization. By 1811, militant Luddites were smashing machines in revolts

over working conditions, and towns like Manchester and Birmingham were already

undergoing the painful metamorphoses that would ultimately transform them into the

shock cities of the industrial era. None of these contemporary social realities appear

in Austen. Mrs Bennet has relatives in respectable trade, but few members of social

classes outside the gentry or upper echelons of the middle class are presentedthe

Bennets housekeeper, for example, is only occasionally referred to as Hill.

344 CAMILLA NELSON

Downloaded from http://adaptation.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Sydney on July 9, 2014

Nevertheless, much of the mystery and menace that is played out in Austen does

relate to class politics. Austen is always acerbic and penetrating in her representation of

the foibles of her own class, but as Raymond Williams has argued, All her discrimination is understandable, internal and exclusive. She is concerned with the conduct of

people who, in the complications of improvement, are repeatedly trying to make themselves into a class. But where only one classis seen, no classes are seen (117). To many

modern readers, there is something discomforting and even violent in this erasure, and

there are numerous uncanny ways in which Grahame-Smiths zombies seem to fill the

shape of this discomfort. In this sense, Grahame-Smiths text could be said to engage

in a radical democratization of Austens work, not by reducing the class dimensions

of the novel (as, for example, an earlier MGM adaptation of Pride and Prejudice did,

democratically distributing silk petticoats and giant bonnets to all of the characters),

but by exacerbating them. In Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, the material possession of

wealth and class actually assumes an increased importance, as only the wealthy are able

to build dojos, employ armies of ninjas, and devote their time to training for combat.

Lady Catherine de Bourgh, for example, is not merely respected for her wealth and

position, but for her deadly combat skillsor rather, wealth, position and class sensibilities are rendered concrete through the retinue of ninjas, the impressive dojo, and

deadly combat skills.

Of course, class politics are a traditional concern of the monster tales from which

the Grahame-Smith text also draws its influences. Franco Moretti famously argued

that Frankensteins monster is the ultimate proletarian monster, the terrifying product

of a system of capital that forms by deforming. In recent times, McNally has extended

Morettis argument, drawing attention to the ways in which the zombie of Haitian folklore has usurped Frankensteins position as a popular metaphor for human life subject

to the depredations of postindustrial capitalism. In Haitian culture, the zombie represents the historical memory of slavery; the image of one human enslaved by the will of

another. In the wake of the global economic crisis, not only the western culture industries but western scholars have appropriated the zombie image for their own use, as a

metaphor not only for individuals but also for social classes and institutions depleted of

their intellectual and affective energies by vampirous capital (hence, Quiggins Zombie

Economics, for example, and at the other end of the political spectrum Drezners Theories

of International Politics and Zombies, in which the author refused to present a Marxist or

Feminist case scenario among the political responses to a zombie invasion he analyses,

on the basis that the Marxists and Feminists would have empathized with the zombies). Indeed, Steven Shaviro in analyzing the zombie phenomenon has argued that

the zombierather like the dereferentialised Austenhas been torn from its historic

roots in Haitian Voodoo, within the material structures of imperialism and colonialism,

becoming a free floating signifier, without referent or origin, endlessly replicating itself,

figuratively and indeed literally. This might assist in explaining why Jane Austen and

zombies seem so aptly paired.

In this sense, it is also interesting to note that zombies are never rendered as individuals in Grahame-Smiths text. They occasionally carry markers that would seem to

point to their status as members of the working classone is clad in a blood encrusted

blacksmiths apron (91), for example, another appears in modest clothing carrying a

Jane Austen Now with Ultraviolent Zombie Mayhem 345

Downloaded from http://adaptation.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Sydney on July 9, 2014

child (92)but they are more commonly designated by generic group descriptors such

as the herd. This herd is constructed as outcast and alien within the textzombies

are commonly called dreadfuls or unmentionables throughout the series, as the Zed

word is deemed unfit for use in polite societyand divided from the uncontaminated

society by a concrete wall or Britains Barrier (117) such as that which encircles the

metropolis of London. This theme of the split societya common motif in monster

talesis also echoed in satirical descriptions of the relationship between the upper and

lower social orders of the uncontaminated, as in the ironic praise of Mr Darcy tendered

by his Pemberley housekeeper, for example, who informs Elizabeth, I have seen him

savagely beat but one servant(197).

This concern with social commentary or what might be construed as an attempt

to democratize Austens text is most readily apparent in the recognizably postfeminist

reconstruction of the kickarse Bennet sisters. In dealing with the gender issues that

are raised in Austens novel the textual strategy is generally to replace verbal sparring with physical combat, mining the theme of bodily excess and bodily humour

in Austen to which scholars such as Jill Heydt-Stevenson have already drawn critical

attention. Elizabeth and Darcy frequently engage in deadly combat with each other, as

well as with the zombies, only to discover that they are equally matched. In this way

the satire seems to be aimed against the strictures of an historic patriarchal society in

which women were regarded as chattel. The official video game of Pride and Prejudice

and Zombies certainly advertises itself in this way, offering a classic beat em up game

experience in which players are advised to upgrade your special attacks while you avoid

both the repulsive undead and deadly repulsive suitors. Yet the paratext provided by

the computer game presents itself as something of an optional extra to many readers of

the novel. In the Grahame-Smith text itself, the potential for an anarchic feminist reading is somewhat blunted by the fact that towards the novels end it is of course Darcy

who turns up on his steed to save a strangely hapless and unprepared Elizabeth, who

is being pursued by zombies on his Pemberley estate. Darcy appears out of nowhere,

like the lone sheriff in a Sergio Leone Western, upon a steed, holding a still smoking

Brown Bess, swathed in gun smoke, his horse letting out a mighty neigh as it reared

upon its hind legs(199).

The image is, of course, ironic but for diehard Austen fans it seems to conjure up the

galloping horses that featured in the opening scene of the 1995 BBC series, through

which writer Andrew Davies attempted to endow Bingley and Darcy with certain masculine qualities. Indeed, the Grahame-Smith text constantly strives to reference the

quality of to-be-looked-at-ness that fuelled the so-called Darcy-mania that accompanied the BBC production, in which the tightness of Darcys trousers famously generated more column inches that any of the womens conspicuously heaving busts. Hence,

the repeated references to Darcys netherparts, the countless anachronistic puns on

the word balls, in addition to the more direct references as when Elizabeths Aunt

informs her, there is something of dignity in the way his trousers cling to those most

English parts of him (206). This is allegedly good fun. Nevertheless, it is clear to some

readers at least that Darcy, as figure of both authority and desire, is produced within

the text via a system of contrasts with an emasculated, unenergetic and thoroughly

unEnglish Otherin short, a zombie. There is also an unsettling sense, as the hero and

346 CAMILLA NELSON

Downloaded from http://adaptation.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Sydney on July 9, 2014

the heroine unite at the tales end, that the gender politics being played out are more

akin to the pre-feminist politics played out in the MGM adaptation of Pride and Prejudice,

in which Elizabeth is allowed to gain the upper hand by besting Darcy in an archery

competition, but all the unruly Bennet sisters are married off and safely subservient at

the storys end. It is therefore incumbent on any feminist critic to point out that in the

historical Austens world a womans choice was invariably one between getting married

and not getting married. Moreover, the consequence of not getting married was invariably one of complete dependence on ones male relativeshence, not much of a choice

at all. However, in the parallel universe of Pride and Prejudice and Zombies the characters

and their situations are in fact utterly transformed. They are, in this sense, entirely different characters. In Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, Elizabeth has a choice between marriage and a career as a zombie slayer and so the decision to marry Darcyin terms of

a feminist reading, at leastseems somewhat forced or false. Interestingly enough, this

is a narrative thread that Hockensmith picks up in the sequel, Dreadfully Ever After, which

opens with Elizabeth bitterly regretting the diminution of her freedom.

In terms of gender politics, the most intriguing element of the Grahame-Smith

adaptation is perhaps the reshaping of the Charlotte Collins plot. In the GrahameSmith adaptation, Charlotte is stricken by a zombie during a walk to Longbourn (the

moment is revealed by Lydia who notices in a comically understated way that Charlotte

had a rather disconcerted look on her face (89)), but nobody save Elizabeth appears

to notice what is happening to Charlotte as the plague takes its toll. Charlotte turns

a ghastly shade of grey, and her table manners are rendered increasingly grotesque.

She gradually looses the capacity to speak. In Austens novel, Charlotte marries Mr

Collins becauserightly or wronglyshe comes to believe that marriage is the only

way to negotiate some limited form of freedom across the repressive discourses of her

time. In Grahame-Smiths text, the entangling of Charlottes fateful decision with her

transformation into the undead works to highlight the ways in which Charlottes life,

and lives of nineteenth-century women in general, were commodified. Charlottes life

is treated as a separable and detachable thing that is no longer seen as integral to her

personhood, but as something that can be alienatedthat is, handed over to somebody

else for a stipulated period of time in return for financial gain, or, in this case, financial

security. Hence, as Charlottes life energies are detached from her person, her body

is reduced to a mere husk or empty shellshe is impelled by a strange and singular

desire (to eat brains), but is otherwise devoid of mind, energy and will. Indeed, in

Grahame-Smiths text, Charlottes situation is depicted with more understanding than

in any other Austen adaptationfor example, despite the democratic renovations of

Lost in Austen, Charlottes failure in marriage results in her being banished to the wilds

of Africa, condemned to disappear from the plot and the television screen altogether.

Charlotte loses her selfhood in Grahame-Smiths text, but it is significant that the loss is

clearly documented and rendered visible. Collins position in the Grahame-Smith plot is

also interesting. On eventually finding out that his beloved has been transformed into

a zombie, Collins valiantly kills himselfaffording his character a greater measure of

redemption than is seen in any other Austen adaptation (ironically, however, he ruins

the possibility of final salvation by allowing Lady Catherine to first behead his beloved

Charlotte on his behalf).

Jane Austen Now with Ultraviolent Zombie Mayhem 347

Dawn of the Dreadfuls and Dreadfully Ever After

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a publisher in possession of a million dollar

bestseller, must be in want of another million dollar bestseller, wrote Jeff Sparrow in the

Melbourne Age, a suspicion that was echoed by critics internationally as Hockensmiths

Dawn of the Dreadfuls found its way into the bookshops. Pride and Prejudice and Zombies

sold close to one million copies in the United States, causing fanworks to proliferate,

or at least, to be picked up by mainstream publishers at a remarkable rate, including,

Downloaded from http://adaptation.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Sydney on July 9, 2014

Charlottes transformation is wonderfully explicable in terms of the politics of

Grahame-Smiths text, but the text contains many apparently anarchic incidents that

are more difficult to explain. One of the most extraordinary is perhaps the scene in

which Elizabeth, wearing a blindfold, slaughters three of Lady Catherines ninjas, each

in a progressively more gruesome waythe last being strangled with his own intestines

before his still beating heart (197) is devoured by a cannibalistic Elizabeth. Fan sites

would perhaps label this image OOC (meaning Out of Character) or worse still FWC

(meaning Fuck With Canon) primarily because it is a scene in whichperhapsthe

excess so undercuts the irony that the satirical point seems somewhat lost. However,

at a deeper level, the image of Elizabeth devouring the still beating heart of a ninja is

profoundly disturbing because it has the effect of adding additional layers of meaning

relating to power and race. In the context provided by Austens de-referentialised storyworld, the soldiers do not leave to fight Bonaparte on the continent or the Savages in

the colonies, rather the external threat is transformed into a domestic one in which the

katana-wielding Bennett sisters become the unlikely figures called upon to participate

in the violent suppression of the Other in the form of the zombieand occasionally

the ninja aswell.

In many novels of Britains imperial age, foreign possessions help to establish wealth

and consequenceand therefore social orderat home. Money from Elsewhere in

the guise of profits from the East India Company, or exotic colonial plantations, provide the means for many a plot resolution in Dickens or Trollope, and Edward Saids

influential study of Mansfield Park has famously argued that Austen may also have taken

the right to these imperial proceeds for granted. In Grahame-Smiths text, the upper

social classes go to the Orient not to acquire wealth, but to acquire the deadly arts

that will allow them to impose order on society in a more direct and violent way. Hence,

despite the apparently democratic renovations of this twenty-first-century adaptation,

the persistence of such cultural blindness is worrying. Grahame-Smiths ninjas, like

the zombies, are figures appropriated from American cartoon culture, and retain the

anarchic violence of that genre. However, the problem is not that the ninjas in the text

are treated cartoonishly, but that the Orient and its Orientals continue to function

within the text as sites of exploitation. This also raises the question as to whether the

use of the zombielike the ninjais in fact another invisibility tactic designed to mask

the presence of historic violence. This is the reading of Grahame-Smiths text that is

consistently mined and extended in Steve Hockensmiths prequel and sequel to Pride

and Prejudice and Zombies, and it is the attempt to deal with the violence entailed in such

images that makes Hockensmiths additions to the series more radical and therefore

interesting.

348 CAMILLA NELSON

Downloaded from http://adaptation.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Sydney on July 9, 2014

Little Women and Werewolves, Little Vampire Women, Alice in Zombieland and Jane Slayre, to

name just a few. At Quirk, Rekulak had also been busy attempting to replicate his own

success. In addition to the prequel and sequel to Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, he had

commissioned and published Sense and Sensibility and Seamonsters and Android Karenina.

The mainstream media were also keeping up with what was now being touted as the

monster mashup phenomenon, as USA Today put it, no classic title or historical figure

is safe.

Hockensmith had already produced a successful fanwork of his own before being

approached by Rekulak, namely Holmes on the Range, a Sherlock Holmes-style mystery set

in the Wild West. In interviews following the launch of Dawn of Dreadfuls Hockensmith

pointed out that his work was part of a wider creative phenomenon thrown up by a

media savvy generation saturated in popular culture. Were really used to having the

power of the zapper: flip, flip, flip, said Hockensmith. People consume things much

more quickly, and in much smaller bites, and I think that lends itself to thinking of

things in a much more slice and dice way. The next logical step is that youre not just

flipping around the dial of your remote, that things are actually combining in some way,

to form new things (Hockensmith, in Keenan). Hockensmiths argument echoes the

position taken by media critics such as Henry Jenkins. People are not merely consumers of popular culture, but active producers of it. New media technologies have not so

much engendered, as given greater visibility to amateur creativity as the extraordinary quality of the user-generated content for Wikipedia or Second Life eloquently shows.

Hockensmiths Dawn of the Dreadfuls and Dreadfully Ever After reference the tactics of

amateur creativity not by deploying the strategies of the mashup as Grahame-Smith

did so much as by extending and drawing out the story world of a prior adaptation. It

is clearly an adaptation of an adaptation.

However, it is interesting to note that despite the repeated invocations of amateur or

fan culture the Quirk book trailer that launched Dawn of the Dreadfuls actually abandons

the edgy amateur aesthetics of the original Pride and Prejudice and Zombies book trailer,

replacing them with expensive period costumes, professional-looking actors and the

kind of high production values that would seem to allude to British Heritage Film. In

the book trailer, a darkly handsome Master Hawksworth announces to the Bennet sisters gathered for combat training in a startlingly white and shiny Georgian dojo, your

days of ease and luxury are over. The next line of dialogue is turned on the potential

consumer. Are you ready? The Bennet sisters answer, Hai!

One of the most striking aspects of the Hockensmith books is that the zombies

though they are still dreadfuls and unmentionablesare no longer nameless and

faceless. Rather, it is clear from the very start that these zombies were once sentient

human beings with lives, loves and occupations. The prequel commences when Mr

Ford, a village apothecary, rises up from his coffin at his own funeral. Ford is a petit

bourgeois shopkeeper with a heavy thumb upon the scales (22) and not much admired

by the Bennets. Consequently, though Elizabeth and Marywho are still young at

this point in the story and yet to be trained in the art of deadly combatinitially

resist Mr Bennets peremptory demand that they lop off Mr Fords head as easy as

pruning a rose, neither are they overly stunned. Mr Ford, in short, is not sympathetic.

Nevertheless, as the series continues, so too does the exploration of political issues

Jane Austen Now with Ultraviolent Zombie Mayhem 349

Downloaded from http://adaptation.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Sydney on July 9, 2014

around class and race. The swelling armies of the stricken are no longer presented as

faceless monsters, but families rising up from the ghastly hovels where they have been

struck dead by poverty, typhoid, cholera or straightforward starvation.

Grotesque figures proliferate within the pages as the drama unfolds. There are military officers sporting mutton chop moustaches, rendered armless and legless, including

one carried around in a wheelbarrow by ensigns called limbs, and another in a cart

drawn by two dogs. Gangs of hungry orphans turn seamlessly from pickpocketing to

brain chomping. The gentry, represented by the cartoonish figures of Lord Lumpley in

the prequel, and Bunny Farquar in the sequel, are shown to be sadistic, irresponsible

and crass. In Dreadfully Ever After, the final book of the trilogy, zombies are run in the

Ascot races for the gentrys amusement, chasing bait in the form of an Irishman, in

an obvious allusion to Britains first imperial project. Indeed, the colonial relationship

with Ireland is a regular feature of the Hockensmith books, with the first zombie wars

nostalgically recollected as the Troubles. As the action escalates, retaliation on the part

of the authorities also becomes increasingly brutal. Infants and toddlers are cut down as

mercilessly as their parents. Entire families are slain. In the final book, tainted citizens

are dragged from their carriages and summarily shot before the gates to the walled city

of London. Theres only one cure for the plague, the executioner informs the hapless, lisping victim (61). What is being played out in the prequel and sequel is of course

the threads of the theme of class and race that sits only slightly below the surface in

Grahame-Smiths textthough the exploration of this theme is arguably foreclosed by

the formal constraints of a mash up with a heavy reliance on 85% Austen. (It is perhaps

worth noting, in this respect, that Ben Winters Sense and Sensibility and Sea Monsters featured only 60% Austen.) Indeed, it may be that the author of an adaptation is only free

from the constraints imposed by the adapted work oncelike Lost in Austens Amanda

Pricethey throw the book into the fountain.

In the Hockensmith books, the zombie problem is overtly presented in relation to the

theme of Englishness. In Dawn of the Dreadfuls, Mr Bennet, a former zombie slayer, recollects how he turned to the East during the Troubles, when others would have preferred an English solution to an English problem (28). Jane Bennets admirer Lieutenant

Tindall is perhaps the most prominent among the characters showing preference for

this English solution. At the novels end, he dies an honourable death at the Battle of

Netherfield Hall, blowing his brains out rather than being contaminated when he finds

himself surrounded by zombies. What Iam is a soldier who loves his country, Tindall

tells Elizabeth. Its traditions. Its values. Everything it stands for. And if we destroy

the unmentionables but allow them to destroy all thatincluding our ideal of genteel

English womanhoodcan we even say weve truly won? (153). Elizabeth, recently

trained for combat at the behest of Mr Bennet, declares that she would rather fight

than remain genteel. Tindall tells her, You must keep faith with those things that have

made England great, Miss Bennet. Elizabeth retorts, General Cornwallis thought that

and last time he was seen feasting on his own dragoons (153). The English solution is

clearly open to criticism.

Elizabeth, in the course of the prequel, is presented with two suitors who personify alternative solutions to the zombie problem. The first is the dashing Master

Hawksworth, who has been hired by Mr Bennet to train his daughters in the art of

350 CAMILLA NELSON

Downloaded from http://adaptation.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Sydney on July 9, 2014

deadly combat. The other is Dr Keckilpenny, who is attempting to invent a solution

to the zombie problem along scientific lines. Keckilpenny opposes the English solution

represented by Tindall. We cant go around being impolite when were about to be

overrun by reanimated cadavers! Egad the English! (101). He devoutly believes that

science will provide a better answer. I would point out that we are now in the nineteenth century. Time has marched on science shall prevail (231). Keckilpenny constructs a laboratory in the attic of the Netherfield mansion that has been transformed

into a military barracks. In the thick of the ensuing battle, as local villagers cower in

the ballroom, as zombie armies overrun the defences, as soldiers are dying in droves, he

refuses to leave off from his work. Keckilpennyit is finally revealedis attempting to

recondition zombies by talking to them gently, whileironically, of coursethey are

simultaneously bound and chained to the wall. Ominously, he refers to this pseudoscientific process as re-Anglification(231).

Keckilpennys scientific solution to the zombie problem is in turn contrasted with

the ideas of Master Hawkesworth, Elizabeths other suitor who has been hired by Mr

Bennet to train his daughters in the deadly arts. [Keckilpenny] puts his faith in the

sciences rather than the deadly arts, Elizabeth explains. Hawkesworth retorts, They

believe we can think our enemies away. Fools! Understanding didnt stop the dreadfuls

last time (129). In spite of these and other noisy warlike declarations, Hawksworth

inevitably turns out to lack the very courage that he protests. Faced with death at the

hands of the zombies, he steals a horse from a hapless soldier in the thick of the battle of Netherfield and runs from the fight. Meanwhile, the zombie that Keckilpenny is

holding captive in his laboratory strikes back at his tormentor and Keckilpenny proves

himself to be a coward of a different sort. Keckilpenny refuses medical treatmentthat

is, by amputationuntil his condition becomes so bad that he, too, must be dispatched.

In short, the zombies in the Hockensmith books are overtly produced as an Other to

Englishness, with its attendant notions of gentlemanliness, and the ideas of sex, class

and race it entails. But it soon becomes clear that it is not zombies, but the spectre of

Otherness itself that is the real target of novels attack. This is particularly apparent in

Dreadfully Ever After, the last book in the series, in which Darcy is stricken by a zombie

child (who is, of course, unceremoniously clobbered), and Elizabeth, now Mrs Darcy,

must locate the mysterious zombie vaccine that according to Lady Catherine de Bourgh

is to be found in a medical clinic run by Dr Farquar in London.

Elizabeth is joined by Kitty and Mr Bennet on this daring quest, but it is Mary,

transformed from a prosy reader of sermons to a feisty fan of Mary Wollstonecrafts

A Vindication of the Rights of Women, who is ultimately responsible for locating the vaccine. Mary slips passed the guards to the gates of Twelve Central in the walled city of

London, and enters a gothic inferno. Corpses are piled waist high in the gutters outside

ramshackle buildings, some with their heads removed or crudely crushed, others ready

to reawaken to darkness at any moment (125). There are naked children, empty bellies

protruding before them like little drums, staring at her with glassy, sunken eyes (125).

There are soldiers tossing the corpses onto the back of a dray already heaped high

beneath the chimneys of a crematorium that spewed black over the nearest rooftops

(125). The gruesome poverty of Twelve Central goes beyond the image of poverty

associated with industrializing cities of the nineteenth century. It is not a representation

Jane Austen Now with Ultraviolent Zombie Mayhem 351

Downloaded from http://adaptation.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Sydney on July 9, 2014

of a city that has been built on industrial growth, so much as on rural dislocation.

In the twenty-first-century context it resembles nothing less than those cities of the

developingsometimes called the majorityworld whose inhabitants must eke out a

living through theft, scavenging and prostitution in what is euphemistically called the

informal economy. Mary comes to the shattering realization that the walls of Twelve

Central were as much for locking this horror in as keeping the dreadfuls out(156).

In Dreadfully Ever After the fear of invasion by alien Others that is represented by the

zombies, alternates with the fear that an exclusionary or divided society may turn into a

kind of cannibalistic communitya nightmarish trap, rotting from within. In this sense

it might be argued that the zombies do not stand for a threat to social order from without, but rather represent the social processes that produce and enforce order. Hence,

the soldiers in Twelve Central use sabres to decapitate the corpses the heaps reaching

as high as Marys chest in spots (165) so the sound of musket shots doesnt disturb the

peace of the gentry in the adjoining suburbs, who are to be kept in continued ignorance

of how very, very wrong the wrong side really was (165). Ultimately, the repressed in

the form of class politics is allowed to return in a blackly comic moment towards the

end of the bookspecifically in the guise of Mr Cricket, who, after a miserable life in

a Whitechapel workhouse followed by an adulthood stoking furnaces at the Hackney

Crematorium and Glue Factory (251), drained of his life energies by an oppressive system of capital, rises from the dismal hovel in which he has perished, and finding himself

transformed into a zombie, enacts a magical revenge (Shapiro 87)by stampeding the

Royal Re-coronation Ceremony and devouring the brains of King GeorgeIII.

However, in the Hockensmith books, the terror of the Other that is such a constant theme of monster narratives most conspicuously plays itself out in the theme

of race. Ninjas, as in the earlier novels, are presented as tools for the violent imposition of social order. They are not only to be used against the undead, but also against

the livingas Elizabeth has found out through her encounters with Lady Catherines

ninjas following her attempts to defy Lady Catherine in the previous book. In Pride and

Prejudice and Zombies, the ninjas are textual figures somewhat akin to the figure of the

household retainer in the nineteenth-century novel. They are fixtures or props in the

text, whose work is necessary to the functioning of the world of the text, but who, in

all other respects, remain anonymous. The ninjas are people on whom the social and

political economy of the text depends, but whose social realityas human beingsdo

not appear to require the readers attention. That is of course until the last book in the

series in which Hockensmith attempts to turn this cultural complacency on itshead.

Indeed, contempt for the ninjas is an attribute that many characters in the Hockensmith

books share. Even Mary, despite her proto-feminist transformation, happily beats up on

the household ninjas when she arrives at Elizabeths temporary residence in London

the house in which Elizabeth, Kitty and Mr Bennet have taken up residence as they

embark on their quest for the zombie vaccine that is needed to cure Darcy. Elizabeth

tells Mary that the household ninjas could not have told Mary where Elizabeth was, for

example, because the ninjas do not speak English. Ah, Mary responds. That would

explain why the conversation was going so poorly (101). Kitty begins to complicate

the relationship between the Bennets and the ninjas by falling in love with the ninja

leader Nezhu, despite what is ironically conjured up as the scandalous fact of his race.

352 CAMILLA NELSON

Downloaded from http://adaptation.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Sydney on July 9, 2014

Kitty is forced to confront her prejudice. She has been taught that ninjas are Sneaky,

deceitful little snakes and dirty, dishonourable, backstabbing curs (144). The ninjas, of

course, are textual figuresthey form an intertext with other genres, specifically, martial arts cartoons. Grahame-Smith calls them Orientals, but Hockensmith makes them

Orientals in the modern sense of the wordthat is, the cultural products of what Said

(Said 2003)has called the wests imperial fantasy, conjured out of countless narratives

of the violent, seductive, deadlyEast.

In Hockensmiths text, it is consciousness of the oppressed Other in the form of

the ninja that provides the solution to the zombie problem. As Mary penetrates to the

heart of Twelve Central, she discovers a locked hospital where a vaccine has indeed

been made that is capable of inoculating the living against the zombie plague. This

vaccine is made of the blood of foreignersand lots of it. Hitherto, this blood has

been obtained from young orphans, such as the Punjabi children Gurdaya and Mohan,

who are held prisoner in the hospital where the sinister Dr Farquar conducts his experiments. Despite the various hurdles thrown up by the plot, it is indeed this sinister vaccine that ultimately cures Darcy of the zombie plague. Darcy and Elizabeth thank the

orphans by adopting themand the reader is presented with a strange pastoral image

of these colonial orphans and ninjas romping through the gardens of Pemberley, some

looked Indian, some Mohammedan, some African. Not one had blond hair or blue eyes

or fair skin(257).

Hence, the nihilistic ending of the zombie narrative, and, indeed, the cautionary

ending of the traditional monster narrative, is forsaken for an apocalyptic ending in

which the hero functions to lead the survivors to a new or promised land where society

will be refounded anew. On one level, it seems that the new pluralistic multicultural

society figured in the novel represents a case of the Empire Striking BackKitty will

undoubtedly marry Nezhu, for example, and presumably give birth to zombie immune

childrenand this is therefore, perhaps, a cause for celebration. However, there is also

something exceedingly disturbing about the metaphors of contagion, vaccination and

cure as they are mobilized in the text. It is an uncomfortable image because it is not one

of recognition of the Other but absorption. As Ziaudin Sardar has argued with respect

to postmodern culture more generally, it takes the ideological mystification of colonialism and modernity to a new, all-pervasive level of control and oppression of the Other

while parading itself as an intellectual alibi for the wests perpetual quest for meaning

through consumption, including the consumption of all Others(40).

The action of the Pride and Prejudice and Zombies trilogy has a carnival character that

is wickedly appealing. The figures of high culture are knocked off their proverbial pedestals and the figures of low culture are resplendently dressed in high cultural garb.

However, it is also important to ponder the ways in which a text that is seemingly so

resolutely about the capitalist grotesque is also in complex ways a product of that same

market processand in this sense the novels carnival values need to be read as market

mediated. Finally, it is important to constantly recollect that the Pride and Prejudice and

Zombies trilogy should not be read as a representation of nineteenth-century British culture, still less as a representation of the hostility and menace of the historical Austen,

but as a product of twenty-first century American culture. It references the historic

violence of nineteenth-century imperialism and capitalism, but only as a figure for the

Jane Austen Now with Ultraviolent Zombie Mayhem 353

ongoing violence of the American Empire as it is experienced in the world today. In

this respect, the image of contagion and inoculationthe literal ingesting of the blood

of Otherslike Money from Elsewhereis an inadequate metaphor for a solution to

the horrors that the final novel otherwise so eloquently proposes.

References

Downloaded from http://adaptation.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Sydney on July 9, 2014

Anderson, Kevin. Zombies Meet Trekkies in New Quirk Books Title. The Independent (6 Mar. 2010). 1

May 2013. www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/books/news/zombies-meet-trekkies-in-newquirk-books-title-1917253.html.

Cartmell, Deborah and ImeldaWhelehan. Adaptations: From Text to Screen, Screen to Text. London: Routledge,

1999.

Constandinides, Costas. From Film Adaptation to Post-Celluloid Adaptation: Rethinking the Transition of Popular

Narratives and Characters Across Old and New Media. London: Continuum International Publishing, 2010.

Dawn of the Dead. Screenplay by James Gunn. Dir. Zack Snyder. Perf. Sarah Polley, Ving Rhames and Jake

Weber. Strike Entertainment and Universal Pictures, 2004. Film.

28 Days Later. Screenplay by Alex Garland. Dir. Danny Boyle. Perf. Cillian Murphy, Naomie Harris,

Christopher Eccleston, Megan Burns and Brendan Gleeson. DNA Films and British Film Council,

2002. Film.

Drezner, Daniel. Theories of International Politics and Zombies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 2011.

Frost, Vicky. Sherlock Series Three: Creators Give Clues About Episodes. Guardian (24 Aug. 2012). Web.

1 May 2013. www.guardian.co.uk/tv-and-radio/2012/aug/24/sherlock-series-three-episodes

Frow, John. Cultural Studies and Cultural Value. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1995.

Galperin, William H. The Historical Jane Austen. Philadelphia, PA: U of Pennsylvania P, 2003.

Goodwin, Christopher. Lizzie Bennet as a Zombie Slayer: Whod Have Believed It? Sunday Times (4 May 2009):

10. EBSCO Host. Newspaper Source Plus. 1 May 2013.

Grahame-Smith, Seth and Jane Austen. Pride and Prejudice and Zombies. Philadelphia, PA: Quirk Books,

2009.

Halford, Macy. Jane Austen Does the Monster Mash. New Yorker Online (Apr. 8 2009). Web. 1 May 2013.

www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/books/2009/04/jane-austen-doe.html.

Heydt-Stevenson, Jill. The Anxieties and Felicities of Rapid Motion: Animated Ideology in Pride and

Prejudice. Austens Unbecoming Conjunctions: Subversive Laughter, Embodied History. New York: Palgrave

Macmillan, 2005: 69102.

Hockensmith, Steve. Dawn of the Dreadfuls. Philadelphia, PA: Quirk Books, 2010.

. Dreadfully Ever After. Philadelphia, PA: Quirk Books, 2011.

Hutcheon, Linda. A Theory of Adaptation. New York: Routledge, Chapman & Hall, 2006.

Jenkins, Henry and David Thorburn, eds. Rethinking Media Change: The Aesthetics of Transition. Cambridge,

MA: MIT Press, 2004.

Jenkins, Henry. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York UP, 2006.

. Fans, Bloggers and Gamers: Exploring Participatory Culture. New York: New York UP, 2006.

Johnson, Claudia. Jane Austen: Women, Politics, and the Novel. Chicago, IL: U of Chicago P, 1990.

Keenan, Catherine. Lost in Austen and Androids. Sydney Morning Herald (2 Apr. 2010). Web. 1 May 2013.

www.smh.com.au/entertainment/books/lost-in-austen-and-androids-20100401-rh8v.html.

Leitch, Thomas. Everything You Always Wanted to Know about Adaptation, Literature/Film Quarterly

33.3 (2005): 23345.

Lost in Austen. Screenplay by Guy Andrews. Dir. Dan Zeff. Perf. Jemima Rooper and Elliot Cowan. ITVMammoth Screen, 2008. Television and DVD.

McNally, David. Monsters of the Market: Zombies, Vampires and Global Capitalism. Boston: Brill, 2011.

Moretti, Franco. Dialectic of Fear. Signs Taken For Wonders: Essays in the Sociology of Literary Forms. New

York: Verso, 2005: 83108.

Night of the Living Dead. Screenplay by George A.Romero and John A.Russo. Dir. George A.Romero. Perf.

Duane Jones, Judith ODea and Karl Hardman. Image Ten, 1968. Film.

Pride and Prejudice. Screenplay by Andrew Davies. Dir. Simon Langton. Perf. Jennifer Ehle and Colin Firth.

BBC1, 1995. Television and DVD.

354 CAMILLA NELSON

Downloaded from http://adaptation.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Sydney on July 9, 2014

Pride and Prejudice. Screenplay by Aldous Huxley, Helen Jerome and Jane Murfin. Dir. Robert Z.Leonard.

Perf. Laurence Olivier and Greer Garson. Metro Goldwyn Mayer, 1940. Film.

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies Book Trailer. Dir. Ami Wright. Quirk Books, 2009. Web. 1 May 2013.

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Dawn of the Dreadfuls Book Trailer. Dir. Charles Haine. Dirty Robber and Quirk

Books, 2010. Web. 1 May 2013.

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies for iPad, iPad and Console. Freeverse and Quirk Books. 2010. Game.

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies Interactive eBook. Text by Seth Grahame-Smith and Jane Austen. PadWorx

Studios and Quirk Books, 2011. eBook.

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Interactive eBook Trailer. PadWorx and Quirk Books, 2011. Web. 1 May 2013.

Poovey, Mary. From Politics to Silence: Jane Austens Non-Referential Aesthetic. A Companion to Jane

Austen. Ed. Claudia L. Johnson and Clara Tuite. Malden, Oxford and Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell,

2012: 25160.

Quiggin, John. Zombie Economic: How Dead Ideas Still Walk Among Us. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 2010.

Rekulak, Jason. Personal Correspondence. 3 May 2013.

Said, Edward. Culture and Imperialism. London: Chatto & Windus, 1993.

Sardar, Ziauddin. Postmodernism and the Other: the New Imperialism of Western Culture. London: Pluto, 1998.

Shawn of the Dead. Screenplay by Edgar Wright and Simon Pegg. Dir. Edgar Wright. Perf. Simon Pegg,

Kate Ashfield and Nick Frost. Studio Canal/Universal Pictures, 2004. Film.

Shaviro, Steven. Cinematic Body. Minneapolis, MN: U of Minnesota P, 1993.

Sparrow, Jeff. Fangs for the Memories The Age (April 17 2010): 22. EBSCO Host. Newspaper Source

Plus. 1 May 2013.

Stam, Robert and Alessandra Raengo, eds. Companion to Literature and Film. Oxford and Maiden: Blackwell,

2004.

Stam, Robert. Literature through Film: Realism. Magic, and the Art of Adaptation. Oxford and Maiden: Blackwell,

2005.

Stam, Robert and Alessandra Raengo, eds. Literature and Film: A Guide to the Theory and Practice of Film

Adaptation. Oxford and Maiden: Blackwell, 2005.

Teeman, Tim. Rev. of Lost in Austen. Times Online (25 Sept. 2008). Web. 1 May 2013. Entertainment.

timesonline.co.uk.

USA Today. In Onslaught of Monsters, no Classic Title or Historical Figure is Safe. USA Today (3 Apr.

2010): 1. EBSCO Host. Newspaper Source Plus. 1 May 2013.

Williams, Raymond. The Country and the City. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1975.

Winters, Ben and JaneAusten. Sense and Sensibility and Sea Monsters. Philadelphia, PA: Quirk Books, 2009.

Вам также может понравиться

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Planning To Write A Film Review: Possible Structure of Your ReviewДокумент1 страницаPlanning To Write A Film Review: Possible Structure of Your ReviewLeo MercuriОценок пока нет

- The 1904 Anthropology Days and Olimpic GamesДокумент491 страницаThe 1904 Anthropology Days and Olimpic GamesLeo Mercuri100% (2)

- Up, Up and Oy Vey! How Jewish History, Culture, and Values Shaped The Comic BookДокумент5 страницUp, Up and Oy Vey! How Jewish History, Culture, and Values Shaped The Comic BookLeo MercuriОценок пока нет

- Invisible Enemies: The American War On Vietnam, 1975-2000Документ549 страницInvisible Enemies: The American War On Vietnam, 1975-2000Leo MercuriОценок пока нет

- Patriots and Patriotism VichyДокумент19 страницPatriots and Patriotism VichyLeo MercuriОценок пока нет

- Robert Brent Topin and Jason Eudy The Historian Encounters Film PDFДокумент7 страницRobert Brent Topin and Jason Eudy The Historian Encounters Film PDFLeo MercuriОценок пока нет

- Hollywood For HistoriansДокумент40 страницHollywood For HistoriansLeo Mercuri100% (4)

- Thomasthompson PDFДокумент19 страницThomasthompson PDFLeo MercuriОценок пока нет

- Kristalnacht Instructions PDFДокумент3 страницыKristalnacht Instructions PDFLeo MercuriОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Senate Bill 859Документ2 страницыSenate Bill 859Sinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneОценок пока нет

- QUESTIONNAIREДокумент5 страницQUESTIONNAIREAyie Azizan100% (1)

- 1984Документ119 страниц1984Ravneet Singh100% (1)

- FijiTimes - Feb 15 2013Документ48 страницFijiTimes - Feb 15 2013fijitimescanadaОценок пока нет

- Billy Elliot EssayДокумент2 страницыBilly Elliot EssaylukeОценок пока нет

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsДокумент2 страницыCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsОценок пока нет

- 1em KeyДокумент6 страниц1em Keyapi-79737143Оценок пока нет

- HR 0355 - Investigation On The Illegal Termination of 416 Filipino Workers by US Businessman Lawrence Kevin Fishman, Owner of Skytech Intl Dental LaboratoriesДокумент2 страницыHR 0355 - Investigation On The Illegal Termination of 416 Filipino Workers by US Businessman Lawrence Kevin Fishman, Owner of Skytech Intl Dental LaboratoriesBayan Muna Party-listОценок пока нет

- The Stony Brook Press - Volume 17, Issue 6Документ20 страницThe Stony Brook Press - Volume 17, Issue 6The Stony Brook PressОценок пока нет

- Format OBC CertificateДокумент2 страницыFormat OBC Certificatevikasm4uОценок пока нет

- Brochure FeminismДокумент3 страницыBrochure FeminismEmmanuel Jimenez-Bacud, CSE-Professional,BA-MA Pol SciОценок пока нет

- Technological Revolution and Its Moral and Political ConsequencesДокумент6 страницTechnological Revolution and Its Moral and Political ConsequencesstirnerzОценок пока нет

- Human Development ConceptДокумент9 страницHuman Development ConceptJananee RajagopalanОценок пока нет

- Keith Motors Site 1975Документ1 страницаKeith Motors Site 1975droshkyОценок пока нет

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Provincial Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsДокумент2 страницыCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Provincial Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsОценок пока нет

- Social and Political StratificationДокумент25 страницSocial and Political StratificationCharisseCarrilloDelaPeñaОценок пока нет

- Vision For A Free and Open Indo-PacificДокумент12 страницVision For A Free and Open Indo-PacificBrian LiberthoОценок пока нет

- Maternity Benefit Act 1961Документ9 страницMaternity Benefit Act 1961Mahesh KumarОценок пока нет

- Daniel Bensaid - On A Recent Book by John Holloway (2005)Документ23 страницыDaniel Bensaid - On A Recent Book by John Holloway (2005)Aaron SmithОценок пока нет

- Document PDFДокумент2 страницыDocument PDFMakhsus AlhanafiОценок пока нет

- Position Paper UCSBДокумент1 страницаPosition Paper UCSBCecil SagehenОценок пока нет

- 2.types of Speeches Accdg To PurposeДокумент4 страницы2.types of Speeches Accdg To PurposeVal LlameloОценок пока нет

- Appointment RecieptДокумент3 страницыAppointment RecieptManan RavalОценок пока нет

- Principles of Management: Managing in The Global ArenaДокумент16 страницPrinciples of Management: Managing in The Global ArenaKumar SunnyОценок пока нет

- Where Did The Dihqans GoДокумент34 страницыWhere Did The Dihqans GoaminОценок пока нет

- James Bowman - A New Era in ScandalogyДокумент5 страницJames Bowman - A New Era in Scandalogyclinton_conradОценок пока нет

- Ten Best Conspiracy Websites Cabaltimes - Com-8Документ8 страницTen Best Conspiracy Websites Cabaltimes - Com-8Keith KnightОценок пока нет

- Special Power of Attourney 5Документ2 страницыSpecial Power of Attourney 5Green JuadinesОценок пока нет

- Pak Us RelationДокумент26 страницPak Us Relationsajid93100% (2)

- Adorno On SpenglerДокумент5 страницAdorno On SpenglerAndres Vaccari100% (2)