Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Trating Food Refusal in Adolescent With Asperger's Disorder

Загружено:

Andreea NicolaeОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Trating Food Refusal in Adolescent With Asperger's Disorder

Загружено:

Andreea NicolaeАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Clinical

Case Studies

http://ccs.sagepub.com/

Treating Food and Liquid Refusal in an Adolescent With Asperger's Disorder

Michael P. Roth, Keith E. Williams and Candace M. Paul

Clinical Case Studies 2010 9: 260 originally published online 18 June 2010

DOI: 10.1177/1534650110373500

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://ccs.sagepub.com/content/9/4/260

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for Clinical Case Studies can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://ccs.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://ccs.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations: http://ccs.sagepub.com/content/9/4/260.refs.html

>> Version of Record - Jul 12, 2010

Proof - Jun 18, 2010

What is This?

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

Treating Food and Liquid

Refusal in an Adolescent

With Aspergers Disorder

Clinical Case Studies

9(4) 260272

The Author(s) 2010

Reprints and permission: http://www.

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/1534650110373500

http://ccs.sagepub.com

Michael P. Roth1, Keith E. Williams2,

and Candace M. Paul2

Abstract

Food refusal is a complicated condition that has both medical and social implications. In this study,

a 16-year-old boy with Aspergers disorder, dependent on gastrostromy tube feedings for

9 years, is treated with a behavioral intervention. The intervention consists of several components,

including stimulus fading for both solids and liquids, a token economy for solids, and an escape

prevention component for liquids. Before treatment, the participant consumes three different

foods and water. After treatment, the participant is consuming 78 foods and 13 beverages. At

the end of 14 days of treatment, all of the participants intakes are received orally, tube feedings

are eliminated, and the patient has gained more than 1 pound on oral feedings. The intervention

is generalized to both home and school settings, and maintenance of treatment gains is reported

by parents 3 months after the end of treatment.

Keywords

food refusal, autism spectrum disorder, token economy, stimulus fading

1 Theoretical and Research Basis

Food refusal has been described as a child failing to consume enough by mouth to maintain nutritional needs and having a height-to-weight ratio below the 5th percentile (Williams, Hendy, &

Knecht, 2008). It has been linked to medical conditions, for example, gastroesophogeal reflux

disease; cystic fibrosis (Field, Garland, & Williams, 2003; Linscheid, 2006; Piazza, Patel, Gulotta,

Sevin, & Layer, 2003); genetic disorders, for example, TreacherCollin syndrome, RusselSilver

syndrome (Ahearn, Castine, Nault, & Green, 2001; Coe et al., 1997); and psychological issues, for

example, choking phobia (Burklow & Linscheid, 2004).

Till date, only one study has examined the use of a token economy in the treatment of food

refusal. Kahng, Boscoe, and Byrne (2003) found that a token economy in conjunction with differential negative reinforcement of alternative behavior was more effective in increasing food

acceptance and reducing refusal behaviors than would a token economy with differential positive reinforcement of alternative behavior with or without physical guidance. Though this study

1

Pennsylvania State University, Harrisburg

Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center

Corresponding Author:

Keith E. Williams, Feeding Program, 905 W. Governor Road, Hershey, PA 17033

E-mail: feedingprogram@hmc.psu.edu

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

261

Roth et al.

demonstrated utility of a token economy as a component of treatment, the study had some

limitations. The study involved only pureed fruits and vegetables and included no foods of

higher texture or other additional food groups such as dairy, fats, grains, and meats. The food

was presented on a Nuk brush, and it was unclear whether there was a transition to other feeding

utensils. Furthermore, it was not reported whether the participant had advanced his feeding skills

at the time of follow-up. This study was, however, unique in that it did not involve the use of

escape prevention.

Although a range of interventions has been used to treat food refusal in children and adolescents, most interventions consist of several components, including some form of escape prevention in which the child is required to consume the food offered (Kerwin, 1999). One escape

prevention procedure, often termed exit criterion, involves having the child to eat a specified

amount of food, often initially a single bite, before being allowed to exit the session (Farrel,

Hagopian, & Kurtz, 2001; Paul, Williams, Riegel, & Gibbons, 2007). Another component that

has been included in interventions for food refusal is some form of stimulus fading, which has

typically involved the gradual increase in bite size or texture (Freeman & Piazza, 1998; Luiselli,

2000; Luiselli, & Gleason, 1987; Paul et al., 2007). Fading has also been used to increase volume of previously avoided drinks without eliciting negative behaviors (Babbitt, Shore, Smith,

Williams & Coe, 2001; Luiselli, Ricciardi, & Gilligan, 2005; Patel, Piazza, Kelley, Ochsner, &

Santana, 2001). This study examined use of a multicomponent intervention that included a

token economy and fading procedure for solid food and a fading procedure plus escape prevention for liquids.

Objectives

The goal of treatment was to eliminate need for gastrostomy tube feeds by increasing the volume

and variety of foods eaten to meet all of the participants nutritional needs. Liquid consumption

would also be increased both to increase caloric intake and to ensure adequate hydration.

2 Case Presentation

Tyler (pseudonym) was a 16-year-old White boy diagnosed with Aspergers disorder. Tyler was

enrolled in a public school and participated in general education classes with his peers. He

attended a learning-support classroom to receive additional instruction for math, but otherwise

received no additional educational services. Tyler resided at home with his biological parents

and younger brother.

3 Presenting Complaints

Tyler was referred to the feeding program, due to lack of weight gain, poor growth, and food

refusal. Before treatment Tylers weight was 29.94 kilograms, and his height was 141centimeters, which was below the 3rd percentile in height and weight compared to boys of his age.

Furthermore, it was calculated that Tyler had the height of an average 10-year-old and the weight

of an average 9.5-year-old.

According to Tylers parents, Tylers began to refuse most foods at 5 years of age but was a

very selective eater at 4 years of age. They also reported that his diet became progressively more

selective until his intake was so limited that he became nutritionally compromised and required

tube feedings. His parents did not report medical conditions that could serve as a possible etiology to his initial food refusal, and a review of his medical records did not reveal possible biological factors. His parents did report that by the age of 16, Tyler had been dependent on gastrostomy

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

262

Clinical Case Studies 9(4)

tube feeds for 9 years. Before treatment, his daily nutritional needs were met predominantly by

32 ounces of Nutren 2.0 formula delivered through gastrostomy tube. Tyler drank only water and

ate small amounts of a specific brand of three different foods. Though these three foodsbowtie

pasta, ham steak, and cerealwere of different textures, Tyler mentioned not liking how some

foods felt in his mouth. In addition to being selective by type and texture, he only used specific

utensils and dishes and only ate dinner. Tyler was given the diagnosis of food refusal as he did

not eat enough to sustain growth; however, he did not fit the more typical pattern of children with

food refusal. A recent review of food refusal examined 38 interventions studies and found that

212 of 218 participants described in these food refusal intervention studies had some form of

medical issue that could have served as an etiology to the food refusal (Williams, Field, &

Seiveling, 2010). In a sample of children referred to feeding programs, the most common feeding problem found among the children with autism spectrum disorders was food selectivity

(Field et al., 2003), but the severity of the feeding problems in these children was not as extreme

as exhibited by Tyler.

4 History

Tyler had a gastrostomy tube placed at 7 years of age, secondary to poor growth and malnutrition.

Other than his chronic refusal to eat, Tyler presented with no medical conditions (e.g., gastroesophageal reflux disease, oral-motor deficits, delayed gastric emptying, vomiting, etc.) that

would have interfered with his ability to eat or drink. Tyler had been diagnosed with Aspergers

disorder as a preschooler. Previous attempts to address his food refusal by community providers

and by two outpatient visits to a feeding program were not successful in improving his food and

beverage intake.

5 Assessment

Before treatment, Tylers parents completed a developmental, medical, and feeding history. The

parents also provided a list of all food and liquids eaten before treatment. In reviewing the history

with Tylers parents, they described behaviors such as refusal to speak on a telephone or demonstrating distress at the sound of a vacuum that rose to the level of specific phobias.

Baseline meals were conducted and data collected on the dependent measures are described

in Section 7.1. In these baseline meals, Tyler was presented with six foods and told he could eat

any of the foods presented but was not required to eat anything. During baseline meals, Tyler

was presented with both the three foods he ate before treatment as well as novel foods from all

food groups. During baseline, Tyler ate only foods he had previously eaten and avoided all novel

foods. After three baseline meals, during which Tyler ate only small amounts of previously eaten

foods, it was decided to implement treatment. As Tyler had only eaten the same foods for several

years, and the baseline meals confirmed this pattern of consumption, it was determined that

additional baseline meals were not necessary.

Potential reinforcers were determined by interviewing both Tyler and his parents. These reinforcers included access to his laptop, preferred videos, and computer games.

5.1 Interobserver Agreement

Interobserver agreement data were recorded to account for experimenter bias while providing

treatment to Tyler. Data were collected by having either an independent observer collecting data

through a one-way observation mirror or by observing videorecordings of meals. These data were

compared to the data collected by the therapist who conducted the meal session. Interobserver

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

263

Roth et al.

agreement for bites consumed, negative vocalization, and gagging was calculated for 28% of the

meals conducted and was calculated to be 93.38%, 100%, and 100%, respectively. For the dependent variable liquid consumed, no agreement data were collected. Each beverage consumed was

weighed before and after treatment (using the same kitchen scale).

5.2 Treatment Integrity

Meals were videorecorded across the course of treatment. These videorecordings were rated

using a 14-item treatment integrity checklist developed by the experimenters to ensure consistent

implementation of treatment procedures. Each video was rated by an experimenter who was not

involved in implementation of the meal being rated. Overall treatment integrity was calculated

to be 99.6% of the 17 sessions recorded.

6 Case Conceptualization

The participants age and high level of functioning makes him dissimilar to not only to previous

patients treated for food refusal in this feeding program (who tend to be younger and have more

significant delays in development) but also to participants in other published food refusal intervention studies (Williams, Field, & Seiveling, 2010). A significant consideration in the development of this intervention were the characteristics of the participant. His parents described him as

being anxious, which led us to focus more on the use of establishing operations and antecedent

manipulations rather than the escape extinction procedures used in past research (Williams &

Seiverling, 2010). Although escape extinction has been shown to be a highly effective component in the treatment of food refusal, like all extinction procedures, it can be accompanied with

negative side-effects such as crying or tantrums. One of the unique aspects to this intervention

was the way in which the daily schedule of meals was presented. Though the daily schedule of

meals is often not mentioned in articles describing the treatment of food refusal, some descriptions of interventions describe participants receiving between three (Linscheid, 2006) and five

(Patel, Piazza, Layer, Coleman, & Swartzwelder, 2005) meals or sessions per day. In this treatment, a meal was presented, the participant completed the meal, exchanged his tokens for time

in his arcade, and then when the time earned in the arcade had elapsed, another meal was

presented. Thus, the participant controlled the number of meals that occurred per day through his

response effort in meals. The greater number of bites and drinks consumed at a meal would not

only result in more minutes spent in his arcade but would also limit the number of meals presented per day. The participant learned this relationship quickly and would verbalize during

meals that he would eat more to get a long break.

Even though this intervention consisted of several components including appetite manipulation, stimulus fading for both solids and liquids, token economy for solids, and escape prevention

for liquids, it was not clear which of the components were necessary in producing the positive

outcome. Appetite manipulation, in this case the elimination of tube feeds, has been suggested as

being the most important component in the treatment of food refusal (Linscheid, 2006) and

was probably important in this intervention. Before elimination of the tube feeds, the participant

was not able to consume enough calories to meet caloric goals, but after elimination of the tube

feeds his intake increased rapidly and dramatically. Before treatment, the participant refused to

taste novel foods to the point of crying and gagging for his parents. The stimulus fading for both

the solids and liquids possibly reduced the response effort to the point that the participant was

able to successfully consume bites and drinks without collateral behaviors. Numerous times

across the course of treatment, the participant verbalized that he liked a particular food or that the

food tasted good to foods that his parents reported he had previously refused without tasting. The

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

264

Clinical Case Studies 9(4)

stimulus fading may have made it possible for the participant to taste novel foods and thus

develop preferences for them. It has been suggested that positive reinforcement alone cannot

increase acceptance of food in children with food refusal but may decrease negative vocalizations and inappropriate behavior in some children (Piazza, 2008).

Although our participant verbalized his liking for the preferred activities in his arcade, it

was not clear whether access to these items was responsible for his eating behavior. Though his

solid and liquid consumption dramatically increased during treatment when compared to baseline, functional control was not demonstrated. We did demonstrate that the treatment package

increased intake when compared to baseline. Though we had planned a usewithdraw design,

removing the token economy, to examine the effectiveness of the treatment, this plan was not

successful. On the fifth day of treatment, meal without the token economy was conducted. At this

meal, the participants intake was equivalent to previous treatment meals. When the participant

was informed that he would not be earning tokens, he stated he liked his arcade, but just really

needed a break, perhaps indicating that the tokens were not as important in increasing feeding

behavior as was the backup reinforcer of earning time for a break. Although the participants

performance in this probe meal was equivalent with meals conducted with the token economy, it

was decided to continue the token economy until his intake goals were met and then eliminate

the token economy for generalization training. For the last 3 days of treatment, the participant

was offered meals without the token economy in a variety of settings in preparation for discharge. This intervention could also be conceptualized as being based on negative reinforcement,

with the participant being able to avoid frequent meals by expending a greater response effort

during meals and taking a greater number of bites and drinks.

Although the solid food portion of this intervention could be conceptualized as being based

on positive reinforcement as tokens were earned for consumption, it is likely that negative reinforcement, in terms of avoiding more frequent meals by expending a greater response effort and

eating more, is a significant factor in the success of the intervention. There was no escape prevention component for solid foods; however, it was included for liquids to ensure a minimal level

of liquid consumption because the participant had been dependent on tube feeds for 9 years and

it was unclear whether he would drink enough to maintain hydration. There were only 11 meals

during the entire course of treatment when the participant had to sit in the therapy room beyond

the 15-minute meal duration to complete his liquids. The escape prevention contingency never

came into effect after the eighth day of treatment. Given the participants success with the food,

it is possible that the escape prevention component was not necessary.

7 Course of Treatment and Assessment of Progress

Treatment sessions were conducted in a therapy room equipped with two tables, three chairs, an

observation window, and a camcorder. Tokens consisted of three stacks of laminated cards in the

shape of a lions paw, each of a different color. Also, an electronic kitchen scale was used to

measure liquid consumption before and after every meal.

7.1 Dependent Measures

Data were collected on four variables. The participants solid intake was measured by bites

consumed, operationally defined as the number of bites the participant placed in his mouth and

swallowed. Liquid consumed was measured in ounces by subtracting the postweights of the

beverages offered from their preweights. Water and other beverages (e.g., milk, juice) were

measured separately. Number of solid foods was used as a measure of diet variety and determined

by counting each food eaten by the participant, but only if two tablespoons of that food was

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

265

Roth et al.

consumed. Number of liquids was also used as a measure of diet variety and was determined by

counting each beverage consumed if at least two ounces were consumed of that beverage. In

addition, data were collected on two aberrant behaviorsnegative vocalization and gagging.

Negative vocalization was defined as any instance where the participant screamed, yelled, cried,

or said no, and/or made negative statements in reference to the presented food. Gagging was

defined as any instance where the participant made gagging sounds or indicated gagging through

neck extensions, tongue protrusions, or changes in skin color.

7.2 Experimental Procedure

Before treatment, all procedures were explained to both the participant and his parents. In

addition, a list of preferred items and activities was provided by the participant.

7.2.1 Solid Food Procedure. All gastrostomy tube feeds were eliminated on Treatment Day

1. The participant was allowed to eat and drink whatever he desired overnight as long as it was

not one of his three preferred foods. On the first day of treatment the participants preferred items

(e.g., laptop computer, DVD player, game consoles) were placed in an empty room in the clinic.

The participant was informed that this room was his arcade and that he could earn time in the

room by taking bites of food. Before the initial meal of each day, the participant and a staff member reviewed a list of ranked foods from a list of 78 different food items (e.g., vegetables, fruits,

meats, starches, fats, and dairy). Foods were ranked either as a Category 1 foodviewed by the

participant as an easy food to eat; a Category 2 foodviewed by the participant as being of

medium difficulty to eat; or a Category 3 foodviewed by the participant as being a very difficult food to eat. For every meal, the participant and the staff member selected six foods from the

food list. The participant was asked to choose two Category 1 foods, two Category 2 foods, and

two Category 3 foods. A meal consisting of these six foods was presented. The participant was

informed that he would earn 1 minute in his arcade per bite of a Category 1 food, 2 minutes

per bite of a category 2 food, and 3 minutes per bite of a category 3 food. Thus, the more difficult

the food was rated, the greater the amount of time he could earn in his arcade. There was no

escape prevention component included for solid foods. Each meal lasted only 15 minutes, and

the end of the meal was marked by the ringing of a timer. The participant was allowed to continue

to eat after the timer rang, but was not required to do so. The participant could only earn tokens

during his 15-minute meals. The length of the participants break between meals was determined

by the number of minutes earned through the token economy.

If the participant consumed a particular food item for three consecutive sessions, the bite size

for that food was increased. All bites started at the size of a grain of rice and progressed to pea

size, then half teaspoon, and finally a full teaspoon. At the end of every day of treatment, the

participant was asked to choose six new foods from his rated categories that he had not chosen

in the sessions conducted that day. This was done to ensure a variety of foods were presented to

the participant across treatment. The participant was permitted to replace a food he had selected

for the day if he consumed at least 15 bites of that food before requesting change. In addition,

once a category had been exhausted, a new food was chosen from another category. For example,

if all foods had been tried from Category 1 and thereby exhausted, or the participant did not rate

any of the foods as being a Category 1 food (easy to eat), then two foods from Category 2, and

four foods from Category 3 were chosen. The participant was permitted to choose foods that he

had previously selected for meals as long as the foods were not offered on the previous day.

7.2.2 Liquid Procedure. During each 15-minute session the participant was presented with

four drinksone from each of the three categories and an 8-ounce cup of water. The participant

was not required to finish all of the water as it was a preferred drink of the participants and was

consumed regularly. He was allowed to consume the beverages throughout the 15-minute meal.

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

266

Clinical Case Studies 9(4)

In meals where the participant did not consume the beverages within the 15-minute period, a

timer was set to record the time that had elapsed between the end of the session and the consumption of the drinks. The participant was required to finish the three rated beverages before

leaving the room and exchanging his tokens. This was the only escape prevention contingency

used in the intervention.

There was also a stimulus-fading criterion for the liquids. If the participant completed any

rated beverage within the 15-minute time limit, the quantity of this particular beverage was

increased by 0.25 ounce. If the participant did not finish a particular drink before the timer rang,

it remained at the same quantity for the next session. Once the drinks were consumed (either

before or after the timer rang), the participant was permitted to exchange the tokens for access to

the arcade. Once the participant was in the arcade, the timer was set to the number of tokens

exchanged (1 bite/1 drink = 1, 2, or 3 minutes of arcade time depending on the rating of food and

drink consumed). On each treatment day, the participant picked three beverages from his rated

liquid list that were not used during the previous treatment day. As it was expected that there

would not be an even distribution of beverages among the three categories, multiple drinks were

sometimes used from the same category. For example, two drinks from Category 2, one drink

from Category 3, and no drink from Category 1. Again, having the child choose different beverages on subsequent days was done to increase exposure to a wider range of drinks.

7.2.3 Liquid Procedure Modified. As gastrostomy tube feeds were eliminated on the first

day of treatment and the participant was not receiving the nutritional supplement administered

through a gastrostomy tube, it was decided to increase milk consumption as a means of increasing the participants daily caloric intake. This was accomplished by modifying the liquid procedure on the third day of treatment. Milk was also systematically increased using the same

criterion as the other beverages. Milk was included for all meals and as milk was increased the

amount of water was decreased by the same amount. Consistent with the other beverages,

changes in volume of milk were not made, unless the milk was completely consumed before the

timer sounded. By the eighth day of treatment, Tyler was drinking a range of beverages in addition to milk and water. It was decided at this point to reduce the number of beverages offered to 3,

one drink from his rated liquid list, milk and water.

7.3 Generalization Training

During the last 3 treatment days, meals were conducted as they would be in the participants

home and school settings. For each meal, the participant was given one main dish or entre

(e.g., Salisbury steak, turkey sandwich, cheeseburger, peanut butter and jelly sandwich, French

toast sticks), and three or four side dishes (e.g., cooked vegetables, salad, fresh fruit, cookies,

chips). During each session for each of these 3 days, no food items were presented consecutively. Data were collected on each bite consumed during each generalization meal. Throughout

the generalization training, no tokens were distributed and no foods were ranked. However, the

participant did receive breaks contingent on the number of bites consumed. It was determined

that if the participant consumed less than 25 bites he would receive a 20-minute break, but if he

consumed 25 bites or more then he received at least a 45-minute break. During these breaks, he

was not permitted to watch preferred videos, play electronic games, or use his laptop. He was

allowed to take walks, look at books, or magazines and converse with parents or staff.

7.4 Outcomes

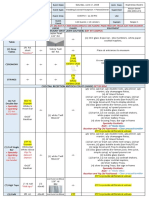

There was a substantial increase in bites consumed across the course of treatment as shown in

Figure 1. As demonstrated in Figure 1, the participant consumed 10 bites in the first treatment

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

267

Roth et al.

Number of bites consumed

60

Baseline

Treatment

Generalization

50

40

30

20

10

0

1

7 10 13 16 19 22 25 28 31 34 37 40 43 46 49 52 55 58 61 64 67 70 73 76 79 82 85 88 91

Meal

Figure 1. Number of bites consumed per meal

Note: The data depict three baseline meals (solid diamond) followed by the treatment package (solid square). A single

probe meal without token economy (open triangle) was conducted with a return to the treatment package. The final

phase depicts generalization without the token economy (open triangle). The graph only shows number of bites and

does not display the increase in bite size that occurred across treatment.

meal and 45 bites on the last treatment meal. As described in the solid food procedure, bite size

for each food was increased as Tyler met criterion for that food; thus, the bite size of each food

started at the size of a grain of rice, then progressed to pea size, half teaspoon, and finally full

teaspoon size. Although not depicted in the graphs, the bite size of foods was increased as each

particular food met criterion. Thus, not only did the number of bites increase across the course of

treatment but the size of the individual bites also increased. Across treatment, the number of

meals per day decreased as the number of bites increased. These changes are shown in Figure 2.

Liquid consumed was measured in terms of ounces consumed, with water and milk displayed

as separate data paths in Figure 3. On the third day of treatment, milk was introduced, and

3.25 ounces were consumed for the day. On the last treatment day, a total of 31 ounces of milk

were consumed. In only 11 of the 93 meals did the participant take longer than the allotted

15 minutes to consume the liquids for a particular meal. All of these 11 meals were in the initial

8 days of treatment.

Again, before treatment, the participant consumed only three foods; at the end of treatment,

the number of solid foods that the participant consumed totaled 78 foods. At the 1-month followup, the participants parents reported he had added an additional 27 new foods to his diet. Before

treatment, the participant drank only water. At the end of treatment, the number of liquids consumed was a total of 13 different drinks and at the 1-month follow-up visit the participant had

added 2 more drinks to his diet. Tyler drank only water before treatment; he drank milk and a

variety of other beverages, mostly juices, by the end of treatment. When analyzing data from the

two aberrant behaviors recorded, negative vocalization and gagging, it was found that on the first

treatment day the participant had engaged in a total eight occurrences of these two behaviors,

and, after the first day of treatment, the participant never exceeded two instances of negative

vocalizing or gagging when combined per day as shown in Figure 4.

Before treatment, the participant was largely dependent on tube feeds, receiving 2000 calories

per day through tube feeds. All tube feeds were eliminated, and the participant remained off all

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

268

Clinical Case Studies 9(4)

Generalization

Treatment

45

40

35

30

25

20

15

Average number of bites

consumed

Meals

10

5

0

10

11

Meals conducted

Average number of bites consumed

BL

50

1

12

13

14

Treatment Day

Figure 2. Average number of bites consumed per treatment day

8

7

BL

Water

Milk

Meals

Treatment

Generalization

8

7

6

10

11

12

13

14

Meals conducted

Average volume consumed (ounces)

Note: This graph depicts the increase in bites per meal across both the treatment and generalization (solid

squares) phases. Stimulus fading was used across the course of the treatment phase, where the size of the bites

was systematically increased. The number of bites increased further across the generalization phase. The graph

only shows average number of bites consumed per day and does not display the average increase in bite size that

occurred across each day.

Treatment day

Figure 3. Average volume of liquids consumed per treatment day

Note: On each day of treatment, the researchers added the total number of ounces consumed for both milk and

water and divided it by the number of sessions conducted each day. The z-axis measures the number of meals

conducted, the abscissa measures what treatment day the data were recorded, and the ordinate measures the

average volume of liquid consumed. The solid black squares represent average water consumption per meal per

treatment day, whereas the solid black circle markers represent average milk consumption per meal per treatment

day. The figure demonstrates that as milk was increased water was decreased, through the specified fading protocol.

Before treatment, the participant only drank water.

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

269

Roth et al.

9

Negative vocalizations

Number of Occurrences

Gagging

Total of abherrant behaviors

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

1

10

11

12

13

14

Treatment day

Figure 4. Aberrant behaviors

Note: The table depicts the data collected for both negative vocalization (open square) and gagging (open diamond)

during each treatment day. As demonstrated, when combining the occurrences of each behavior (open circle), the

behaviors never appeared more than twice after the initial day of treatment.

tube feeds at the 1-month follow-up. Across the 3-week course of treatment, the participant

gained 1 pound and 4 ounces.

7.5 Social Validation of Treatment Protocol

A total of 5 weeks after the conclusion of the study, the participants parents were sent a satisfaction questionnaire. They were asked 13 questions pertaining to their satisfaction of the program

and using a 5-point Likert-type scale, they reported the highest level of satisfaction for every

question. The parents also reported that family meals were more enjoyable and that family stress

was reduced. The parents also provided additional comments describing their childs success

stating that now their child never hesitates to taste a novel food, began bringing a lunch to school,

and even eats leftover food from other family members plates.

8 Complicating Factors

There were no complicating factors in the clients history of significant importance that was not

already discussed in the client history section. Tyler was compliant for a majority of treatment

and displayed low rates of inappropriate behavior as demonstrated in Figure 4.

9 Managed Care Considerations

Tylers treatment was rapid and produced long-term success. In a previous study, the cost of tube

feeding was reported for several patients. The lowest of the costs reported was US$16, 320 per

year for the cost of the tube feeding supplies and formula (Williams, Riegel, Gibbons, & Field,

2007). Tylers treatment was paid by state medical assistance who was charged less than US$500/

day as a result of a contractual arrangement between the medical facility and the medical

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

270

Clinical Case Studies 9(4)

assistance program and the state. We estimate the cost of treatment to the state medical assistance

program was lower than the cost of tube feeding for a period of 1 year. Tyler had received tube

feedings for 9 years; if intensive treatment had been provided earlier with this same level of success, the cost savings would have been substantial.

10 Follow-Up

Follow-up visits were scheduled 2 and 4 weeks after treatment in the clinic. During these visits,

Tyler and his parents met with the licensed psychologist and graduate intern feeding therapist to

discuss ongoing progress, to record stature to weight proportions and answer any questions that

Tyler and his parents may have had, and to construct a timeline for the complete removal of

Tylers gastrostomy tube. It was decided at these follow-up meetings that the gastrostomy tube

would be removed in the spring due to the predicted active flu season. In addition, follow-up was

also conducted over the phone once a week for 2 months. During the placed phone calls, Tylers

variety of foods and liquids consumed as well as any weight or height gains that were made since

the previous visit or phone call were discussed.

As discussed earlier, Tyler continued to add new foods and beverages to his diet after discharge. He eats meals without the token economy and is gaining weight at faster rate than when

he was dependent on tube feedings.

11 Treatment Implications of the Case

It is with little argument that gastrostomy tubes and other tube feeding methods (e.g., nasogastric

intubation) can be considered life saving. However, the effect of gastrostomy tube placement on

an individuals quality of life has been reported as being both physically and socially intrusive

and producing adverse psychological consequences (Jordan, Philpin, Warring, Cheung, &

Williams, 2006). The current study demonstrated a successful intervention for the treatment of

food refusal that was brief in duration (14 days), easy to implement, and generalized to both the

home and school settings. This type of intervention, in which the number of meals and the duration of reinforcement is dependent on the participants amount of response effort, may be well

suited for older children or adolescents who could understand the contingencies and for whom

more intrusive escape prevention techniques are less socially acceptable.

12 Recommendations to Clinicians and Students

To further develop the literature in this area, it is recommended that future clinicians and students

attempt a scientific design that underlines the effectiveness of each component of this treatment

package. Though it is believed that the combination of appetite manipulation, stimulus fading,

and reinforcement made the treatment successful, the contribution of each component was not

assessed.

This study also had the participant evaluate the difficulty of each novel food and rate each

food on the basis of the perceived difficulty in eating that food. Although this was not difficult

for staff, it was not clear whether this was necessary. It is also recommended that future studies

examine other possible alternatives to having a participant earn break time without having to

rank foods according to a level of perceived difficulty.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared that they had no conflicts of interests with respect to their authorship or the publication of this article.

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

271

Roth et al.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article.

References

Ahearn, W. H., Castine, T., Nault, K., & Green, G. (2001). An assessment of food acceptance in children

with autism or pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31, 505-511.

Babbitt, R. L., Shore, B. A., Smith, M., Williams, K. E., & Coe, D. A. (2001). Stimulus fading in the treatment of adipsia. Behavioral Interventions, 16, 1-11.

Burklow, K. A., & Linscheid, T. (2004). Rapid inpatient behavioral treatment for choking phobia in

children. Childrens Health Care, 33, 93-107.

Coe, D. A., Babbitt. R. L., Williams, K. E., Hajimihalis, C., Snyder, A. M., Ballard, C., . . . Efron, L. A.

(1997). Use of extinction and reinforcement to increase food consumption and reduce expulsion. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 30, 581-583.

Farrel, D. A., Hagopian, L. P., & Kurtz, P. F. (2001). A hospital- and home-based behavior intervention

for a child with chronic food refusal and gastrostomy tube dependence. Journal of developmental and

Physical Disabilities, 13, 407-418.

Field, D., Garland, M., & Williams, K. (2003). Correlates of specific childhood feeding problems. Journal

of Paediatric and Child Health, 39, 299 -304.

Freeman, K. A., & Piazza, C. C. (1998). Combining stimulus fading, reinforcement, and extinction to treat

food refusal. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 31, 691-694.

Jordan, S., Philpin, S., Warring, J., Cheung, W. Y., & Williams, J. (2006). Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomies: The burden of treatment from a patient perspective. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 56, 270-281.

Kahng, S., Boscoe, J. H., & Byrne, S. (2003). The use of escape contingency and a token economy to

increase food acceptance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 36, 349-353.

Kerwin, M. E. (1999). Empirically supported treatments in pediatric psychology: Severe feeding problems.

Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 24, 193-214.

Linscheid, T. R. (2006). Behavioral treatments for pediatric feeding disorders. Behavior Modification, 30,

6-23.

Luiselli, J. K. (2000). Cueing, demand fading, and positive reinforcement to establish self-feeding and oral

consumption in a child with chronic food refusal. Behavior Modification, 24, 348-358.

Luiselli, J. K., & Gleason, D. J. (1987). Combining sensory reinforcement and texture fading procedures

to overcome chronic food refusal. Journal of Behavioral Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 18,

149-155.

Luiselli, J. K., Ricciardi, J. N., & Gilligan, K. (2005). Liquid fading to establish milk consumption by a

child with autism. Behavioral Interventions, 20, 155-163.

Patel, M.R., Piazza, C.C., Kelly, M.L., Ochsner, C.A., & Santana,C.M. (2001) Using a fading procedure

to increase fluid consumption in a child with feeding problems. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,

34, 357 -360.

Patel, M. R., Piazza, C. C., Layer, S. A., Coleman, R., & Swartzwelder, D. M. (2005). A systematic evaluation of food texture to decrease packing and increase oral intake in children with pediatric feed disorder.

Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 38, 89-100.

Paul, C., Williams, K. E., Riegel, K., & Gibbons, B. (2007). Combining repeated taste exposure and escape

prevention: An intervention for the treatment of extreme food selectivity. Appetite, 49, 708-711.

Piazza, C. C. (2008). Feeding disorders and behavior: What have we learned? Developmental Disabilities

Research Reviews, 14, 174-181.

Piazza C. C., Patel M. R., Gulotta, C. S., Sevin, B. M., & Layer, S. A. (2003). On the relative contributions

of positive reinforcement and escape extinction in treatment of food refusal. Journal of Applied Behavior

Analysis, 36, 309-324.

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

272

Clinical Case Studies 9(4)

Williams, K. E., Hendy, H., & Knecht, S. (2008). Parent feeding practices and child variables associated

with childhood feeding problems. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 20, 231-242.

Williams, K.E., Seiverling, L., & Field, D.G. (2010). Food refusal: A review of the literature. Research in

Developmental Disabilities, 31, 625-633.

Williams, K. E., Riegel, K., Gibbons, B., & Field, D. G. (2007) Intensive behavioral treatment for severe

feeding problems: A cost-effective alternative to tube feeding. Journal of Physical and Developmental

Disabilities, 19, 227-235.

Bios

Michael Roth, M.A., recently graduated with his Masters in Applied Behavior Analysis from the Penn

State University, Harrisburg Campus. His clinical interests include working with children with autism spectrum disorders.

Keith Williams, Ph.D., is the Director of the Feeding Program at the Penn State Hershey Medical Center.

His research interests include the study of ingestive behaviors in children with chronic health problems.

Candace Paul, M.A., is a Feeding Therapist II in the Feeding Program at the Penn State Hershey Medical

Center. Her research interests include working with children with food selectivity and choking phobias.

Downloaded from ccs.sagepub.com by Andreea Nicoleta Nicolae on October 12, 2011

Вам также может понравиться

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Behavioral Activation in Breast Cancer PatientsДокумент14 страницBehavioral Activation in Breast Cancer PatientsAndreea NicolaeОценок пока нет

- An Investigation of Health Anxiety in FamiliesДокумент12 страницAn Investigation of Health Anxiety in FamiliesAndreea NicolaeОценок пока нет

- Don't Kick Me OutДокумент14 страницDon't Kick Me OutAndreea NicolaeОценок пока нет

- Internet-Related Psychopathology Clinical Phenotypes and PerspectivesДокумент138 страницInternet-Related Psychopathology Clinical Phenotypes and PerspectivesAndreea NicolaeОценок пока нет

- Behavioral Activation As An Intervention For Coexistent Depressive and Anxiety SymptomsДокумент13 страницBehavioral Activation As An Intervention For Coexistent Depressive and Anxiety SymptomsAndreea NicolaeОценок пока нет

- Treating Depression in Prison Nursing HomeДокумент21 страницаTreating Depression in Prison Nursing HomeAndreea NicolaeОценок пока нет

- The Five Therapeutic RelationshipsДокумент16 страницThe Five Therapeutic RelationshipsAndreea Nicolae100% (2)

- The Use of Homework Success For A Child With Attention-Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder, Predominantly Inattentive TypeДокумент14 страницThe Use of Homework Success For A Child With Attention-Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder, Predominantly Inattentive TypeAndreea NicolaeОценок пока нет

- Behavioral Therapy For Anxiety DisordersДокумент18 страницBehavioral Therapy For Anxiety DisordersAndreea NicolaeОценок пока нет

- Occupational Stress Fractors That Contribute To Its Occurrence and Effective ManagementДокумент158 страницOccupational Stress Fractors That Contribute To Its Occurrence and Effective ManagementAnonymous 0zM5ZzZXCОценок пока нет

- A Time-Series Study of The Treatment of Panic DisorderДокумент21 страницаA Time-Series Study of The Treatment of Panic Disordermetramor8745Оценок пока нет

- Clinical Case Studies.Документ14 страницClinical Case Studies.Andreea NicolaeОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Member Rewards Catalogue 2020/21 EditionДокумент22 страницыMember Rewards Catalogue 2020/21 EditionNORMALA ABDUL RANIОценок пока нет

- Determining Textual EvidenceДокумент4 страницыDetermining Textual EvidenceKaren R. Royo100% (4)

- The Most Wanted Rice Cooker - Google SearchДокумент15 страницThe Most Wanted Rice Cooker - Google SearchDoni RandanuОценок пока нет

- Times Leader 09-19-2012Документ40 страницTimes Leader 09-19-2012The Times LeaderОценок пока нет

- Science 4 - q1 - Module 4of6 - Changes That Mareials Undergowhen Mixed With Other Materials - v2Документ20 страницScience 4 - q1 - Module 4of6 - Changes That Mareials Undergowhen Mixed With Other Materials - v2Mary Ann BernalesОценок пока нет

- FFD ProgramДокумент4 страницыFFD ProgramMarkYamaОценок пока нет

- A Christmas Crossword PuzzleДокумент3 страницыA Christmas Crossword Puzzlemakbuddy50% (2)

- Market Survey ReportДокумент6 страницMarket Survey ReportxulphikarОценок пока нет

- 18 - Student Guide VolksgartenДокумент3 страницы18 - Student Guide Volksgartenanon_383527604Оценок пока нет

- Trends and Status of Public Service Delivery in UgandaДокумент151 страницаTrends and Status of Public Service Delivery in UgandaOnziki Adelia MosesОценок пока нет

- Activity EnglishДокумент2 страницыActivity EnglishJennefer Arzaga OlaОценок пока нет

- Menu Punjabi TadkaДокумент4 страницыMenu Punjabi TadkaSheikh Muhammed TadeebОценок пока нет

- Captains Packet - Lemon&Lime Aysa & Briggs 06-15-23Документ68 страницCaptains Packet - Lemon&Lime Aysa & Briggs 06-15-23OSCAR LUIS JUSTINIANO ARIASОценок пока нет

- VadilalДокумент84 страницыVadilalMIltaniyoОценок пока нет

- Getting Laid in NYCДокумент19 страницGetting Laid in NYCAlberto Ronin Gonzalez100% (2)

- Case-Study OB (Individual Work)Документ4 страницыCase-Study OB (Individual Work)Dilana ChalayaОценок пока нет

- The Scholarship - Isabella MarconДокумент40 страницThe Scholarship - Isabella Marconapi-595140229Оценок пока нет

- Teaching Plan For DiabetesДокумент4 страницыTeaching Plan For DiabetesanrefОценок пока нет

- Mayr Franz. Zulu ProverbsДокумент10 страницMayr Franz. Zulu ProverbsAzarias VilanculosОценок пока нет

- The Food Song - Kids + Children Learn English SongsДокумент2 страницыThe Food Song - Kids + Children Learn English SongsWilliam JimenezОценок пока нет

- I G Economics SampleДокумент12 страницI G Economics SampleNietharshan Eapen100% (1)

- Text For No. 1 - 4: A. Choose One Correct Answer Out of The Four Options Given!Документ7 страницText For No. 1 - 4: A. Choose One Correct Answer Out of The Four Options Given!Lisa Aprilia AprisaОценок пока нет

- The Puerto Rican StoryДокумент11 страницThe Puerto Rican StoryellenquiltОценок пока нет

- Young's MMPL Pricelist 2022Документ6 страницYoung's MMPL Pricelist 2022Newstar EaОценок пока нет

- Text 1 You Will Read A Passage About Competitive Eating. Answer The Questions Based On What You Have ReadДокумент4 страницыText 1 You Will Read A Passage About Competitive Eating. Answer The Questions Based On What You Have ReadCaroline Cezario Meme75% (4)

- Nandini NehraДокумент102 страницыNandini NehraShivraj CyberОценок пока нет

- Qse Adv TG 09 Exam Answer KeyДокумент4 страницыQse Adv TG 09 Exam Answer KeyCristian GutierrezОценок пока нет

- Kasān Haida Full PhrasebookДокумент10 страницKasān Haida Full Phrasebooklanguage warrior100% (1)

- Year 4 - Familiarisation Pack-2022-Answers-14 July 2023Документ17 страницYear 4 - Familiarisation Pack-2022-Answers-14 July 2023s.amnafaisalОценок пока нет

- Workbook Answer Key: Unit 9Документ1 страницаWorkbook Answer Key: Unit 9Управление ПерсоналомОценок пока нет