Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Seminar 02 Perfectionism and Motivation

Загружено:

Dana RoxanaАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Seminar 02 Perfectionism and Motivation

Загружено:

Dana RoxanaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Personality and Individual Dierences 42 (2007) 13791389

www.elsevier.com/locate/paid

Perfectionism in adolescent school students: Relations

with motivation, achievement, and well-being

Joachim Stoeber

a

b

a,*

, Anna Rambow

Department of Psychology, University of Kent, Canterbury, Kent CT2 7NP, United Kingdom

Department of Educational Sciences, Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg, Germany

Received 7 May 2006; received in revised form 3 October 2006; accepted 6 October 2006

Available online 21 November 2006

Abstract

Positive conceptions of perfectionism (Stoeber & Otto, 2006) suggest that striving for perfection is associated with positive characteristics and adaptive outcomes. To investigate whether this also holds for adolescent school students, a sample of 121 ninth-graders completed measures of perfectionism at school

(striving for perfection, negative reactions to imperfection), perceived parental pressure to be perfect, motivation, school achievement, and well-being. Results showed that negative reactions to imperfection were

related to fear of failure, somatic complaints, and depressive symptoms; and perceived parental pressure

was related to somatic complaints. In contrast, striving for perfection was related to hope of success, motivation for school, and school achievement. Moreover, striving for perfection showed a negative correlation

with depressive symptoms, once the inuence of negative reactions to imperfection was partialled out. The

ndings show that striving for perfection in adolescent school students is associated with positive characteristics and adaptive outcomes and thus may form part of a healthy pursuit of excellence. Negative reactions to imperfection and perceived parental pressure to be perfect, however, are associated with negative

characteristics and maladaptive outcomes and thus may undermine adolescents motivation and well-being.

2006 Published by Elsevier Ltd.

Keywords: Perfectionism; Adolescence; Motivation; Fear of failure; Hope of success; Academic achievement;

Well-being; Depression

Corresponding author. Tel.: +44 1227 824196; fax: +44 1227 827030.

E-mail address: J.Stoeber@kent.ac.uk (J. Stoeber).

0191-8869/$ - see front matter 2006 Published by Elsevier Ltd.

doi:10.1016/j.paid.2006.10.015

1380

J. Stoeber, A. Rambow / Personality and Individual Dierences 42 (2007) 13791389

1. Introduction

Individuals with high levels of perfectionism are characterized by striving for awlessness and

setting of excessively high standards for performance accompanied by tendencies for overly critical evaluations of their behavior (Flett & Hewitt, 2002; Frost, Marten, Lahart, & Rosenblate,

1990). This may have positive and negative consequences: While setting high standards may have

positive consequences such as higher motivation and higher achievement (Bieling, Israeli, Smith,

& Antony, 2003), being overly self-critical may reduce well-being and put individuals at risk for

depression (Dunkley, Blankstein, Masheb, & Grilo, 2006). Consequently, when investigating perfectionism, it is important to dierentiate between two major dimensions of perfectionism (Frost,

Heimberg, Holt, Mattia, & Neubauer, 1993; Stoeber & Otto, 2006). On the one hand, there is the

positive dimension of perfectionistic strivings representing perfectionists high standards for performance. This dimension has also been described as normal, healthy, or adaptive perfectionism.

On the other hand, there is the negative dimension of perfectionistic concerns representing perfectionists negative attitudes towards mistakes, harsh self-criticism, and feelings of discrepancy between performance and expectations. This dimension has also been described as neurotic,

unhealthy, or maladaptive perfectionism (Hamachek, 1978; Rice, Ashby, & Slaney, 1998; Stumpf

& Parker, 2000; Terry-Short, Owens, Slade, & Dewey, 1995).

In a recent review on the dierences between these two dimensions (Stoeber & Otto, 2006), the

perfectionistic strivings dimension was found to be related to positive characteristics such as conscientiousness, endurance, positive aect, and satisfaction with life. Moreover, it was found to be

related to academic achievement, regarding both specic exams and overall academic performance: College students with higher levels of perfectionistic strivings received higher grades in

a mid-term exam than those with lower levels of perfectionistic strivings (Bieling et al., 2003). Furthermore, students classied as adaptive perfectionists (high perfectionistic strivings and low perfectionistic concerns) showed a higher grade point average than maladaptive perfectionists (high

perfectionistic strivings and high perfectionistic concerns) and nonperfectionists (low perfectionistic strivings) (Grzegorek, Slaney, Franze, & Rice, 2004; Rice & Slaney, 2002). In contrast, the

perfectionistic concerns dimension was found to be related only to negative characteristics, the

most prominent of these being depression and anxiety (Stoeber & Otto, 2006).

While there is a plethora of studies on perfectionism in college students, our knowledge about

perfectionism in adolescent school students is still very limited. So far, only four studies have

investigated how perfectionism relates to motivation, school achievement, and well-being in adolescent school students (Accordino, Accordino, & Slaney, 2000; Einstein, Lovibond, & Gaston,

2000; Nounopoulos, Asbhy, & Gilman, 2006; Vandiver & Worrell, 2002). Employing Hewitt

and Fletts multidimensional measure of pefectionism (Hewitt & Flett, 1991), Einstein et al.

(2000) investigated how self-oriented and socially prescribed pefectionism related to motivation,

school engagement, and well-being in high school students prior to a period of major exams. They

found that self-oriented perfectionismwhich is a core facet of the perfectionistic strivings dimension (Stoeber & Otto, 2006)was related to self-reported motivation for the upcoming exams and

number of hours spent studying per week, indicating that students who strive for perfection are

more motivated and more engaged at school than students who do not strive for perfection.

Moreover, self-oriented perfectionism was also related to stress, indicating that school students

who strive for perfection may also feel under greater pressure than students who do not strive

J. Stoeber, A. Rambow / Personality and Individual Dierences 42 (2007) 13791389

1381

for perfection. However, the relationship between self-oriented perfectionism and stress was only

small and failed to reach signicance once the inuence of socially prescribed perfectionisma

core facet of the perfectionistic concerns dimensionwas partialled out. Socially prescribed perfectionism was unrelated to motivation and engagement, but showed signicant correlations with

stress, depression, and anxiety. Employing Slaney et al.s multidimensional measure of perfectionism (Slaney, Rice, Mobley, Trippi, & Ashby, 2001), Accordino et al. (2000) found that

discrepancy between performance and expectationsanother core facet of perfectionistic concernswas related to higher depression in school students of grades 1012. In contrast, high standardsa core facet of perfectionistic strivingswere related to mastery orientation (indicating a

preference for challenging tasks), work orientation (reecting the desire to work hard), and higher

grade point average. Similar ndings are reported by two further studies (Nounopoulos et al.,

2006; Vandiver & Worrell, 2002) that investigated perfectionism and school engagement in middle school students, and that also found high standards to be related to higher grade point

average.

While the studies suggest that perfectionistic strivings in adolescent school students are related

to higher levels of motivation, achievement, and well-being, there remain some questions. First,

the studies indicate that students who strive for perfection are more motivated. However, they

do not address the question of whether they are more motivated by the motive to achieve success

(hope of success) or by the motive to avoid failure (fear of failure) (Atkinson, 1957). Studies have

shown that hope of success and fear of failure may have contrary eects on students achievement

and task engagement and that perfectionism is related to both motives (Frost & Henderson, 1991;

Slade & Owens, 1998). In a series of studies on perfectionism in athletes (Stoeber & Becker, submitted for publication; Stoeber, Otto, & Stoll, 2005), negative reactions to imperfection were

found to be related to fear of failure and somatic complaints. In contrast, striving for perfection

was found to be related to hope of success and number of hours of training, suggesting that only

striving for perfection is related to success motivation and greater engagement whereas negative

reactions to imperfection are related to failure motivation and lower well-being. Consequently, it

would be important to dierentiate striving for perfection from negative reactions to imperfection.

Moreover, it would be important to take into account recent ndings that perfectionistic tendencies in school may dier from global perfectionistic dierences (Dunn, Gotwals, & Dunn, 2005).

Therefore, when looking at perfectionism in relation to motivation, achievement, and well-being

in school students, this would suggest the need to investigate students perfectionism at school, not

their global perfectionism. Finally, it would be important to investigate the role that parental pressure to be perfect plays in the relationship between perfectionism and school students motivation,

achievement, and well-being. Previous research has found perceived parental pressurecomprising perceived parental expectations to be perfect and perceived parental criticism for not being

perfect (Stober, 1998; Stumpf & Parker, 2000)to be related to psychological maladjustment, somatic complaints, and depressive symptoms in both sixth-graders and college students (Hill et al.,

2004; Stober, 1998; Stumpf & Parker, 2000). Thus parental pressure to be perfect is a factor that

should be taken into account when looking at perfectionism in adolescent school students.

Against this background, the aim of the present study was to investigate further the relationship

between perfectionism and motivation, school achievement, and well-being in adolescent school

students by examining how two aspects of perfectionism at school (striving for perfection, negative reactions to imperfection) relate to motivation (hope of success, fear of failure, motivation for

1382

J. Stoeber, A. Rambow / Personality and Individual Dierences 42 (2007) 13791389

school), school achievement (grades), and well-being (somatic complaints, depressive symptoms),

and what role perceived parental pressure plays in these relationships. In line with evidence that

striving for perfection is related to healthy and adaptive characteristics whereas negative reactions

to imperfection are related to unhealthy and maladaptive characteristics (e.g., Stoeber & Otto,

2006; Stoeber, Otto, Pescheck, Becker, & Stoll, in press; Stoeber & Rennert, 2005), we expected

striving for perfection to be related to hope of success and higher achievement. In contrast, we

expected negative reactions to imperfection and perceived parental pressure to be related to fear

of failure and lower well-being.

2. Method

2.1. Participants and procedure

A sample of N = 121 adolescent school students (59% female) attending ninth-grade was recruited at two high schools in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. Mean age of participants was 14.6 years

(SD = 0.7, range = 1417). Questionnaires were administered in the classrooms during class time.

While a school teacher was present to ensure student attendance, all distribution and collection of

questionnaires were handled by the second author as were all instructions. As all students were

under the age of 18, informed consent was obtained from both students and parents.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Perfectionism

To measure perfectionism at school (striving for perfection, negative reactions to imperfection),

the 10 items that Stoeber et al. (in press) used to measure striving for perfection and negative reactions in sport were employed, modied to apply to the school context (see Appendix). To measure

perceived parental pressure to be perfect, the Perceived Parental Pressure subscale of the Multidimensional Inventory of Perfectionism in Sport (Stober, Otto, & Stoll, 2004 [available from rst

author upon request]) was employed which comprises eight items that make no special reference

to sport and consequently were left unmodied (see Appendix). To all items, participants responded on a six-point scale from 1 = never to 6 = always.

2.2.2. Motivation

Two measures of motivation were included. First, as a general measure, the Achievement Motivation Scale (Gjesme & Nygard, 1970; German version in Dahme, Jungnickel, & Rathje, 1993)

was employed. The scale comprises 30 items, of which 15 measure hope of success (e.g., I enjoy

tasks that are challenging) and 15 fear of failure (e.g., I dont enjoy working on tasks that I am

not sure to master). Second, as a school-specic measure, participants responded to the Motivation for School scale (Stober, 2002 [available upon request]) which comprises nine items measuring students motivation for school (e.g., In the morning, I look forward to going to school and

learning something new). To all items, participants responded on a six-point scale from 1 = totally disagree to 6 = totally agree.

J. Stoeber, A. Rambow / Personality and Individual Dierences 42 (2007) 13791389

1383

2.2.3. Grades

To measure school achievement, participants self-reported the grades they had received in German, English, and Math on their last report. These three subjects are the core subjects of the German school curriculum and mandatory for all ninth-grade students. Grades were averaged across

the three subjects to form a mean score of grades (see Table 1). Because grades in Germany range

from 1 = very good to 6 = unsatisfactory, comparable to grades AF in US American

schools, mean scores were reversed before computing correlations so that higher grades indicate

higher achievement.

2.2.4. Well-being

To measure well-being, participants responded to the somatic complaints subscale of the Bern

Subjective Well-Being Questionnaire for Adolescents (Grob et al., 1991) which comprises eight

items measuring common somatic complaints of adolescents (e.g., headache, feeling dizzy). Moreover, they responded to the short form of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

(Radlo, 1977; German version, ADS-K, by Hautzinger & Bailer, 1993) which comprises 15 items

measuring depressive symptoms in the general population (e.g., feeling sad, restless sleep). For

both scales, participants indicated how often they had experienced each symptom during the past

week responding on a four-point scale from 0 = seldom or not at all (less than 1 day) to

3 = more often than not or all the time (57 days).

2.3. Preliminary analyses

All measures displayed satisfactory reliability (see Table 1). In line with previous ndings (Pomerantz, Altermatt, & Saxon, 2002), female students reported higher grades, t(117) = 2.16, p < .05

Table 1

Descriptive statistics

Measure

Perfectionism at school

Striving for perfection

Negative reactions to imperfection

Perceived parental pressure

Motivation

Hope of success

Fear of failure

Motivation for school

Grades

Well-being

Somatic complaints

Depressive symptoms

SD

3.13

2.85

2.73

1.20

0.98

1.25

.88

.78

.94

62.33

47.97

29.84

2.50

11.89

13.78

7.85

0.79

.89

.92

.79

.76

4.77

14.62

4.24

8.03

.76

.86

Note: N = 119121 adolescent school students. Perceived parental pressure = perceived parental pressure to be perfect.

In line with previous publications, mean scores were computed for striving for perfection, negative reactions to

imperfection, and perceived parental pressure to be perfect (cf. Stober et al., 2004; Stoeber et al., in press). Grades are

self-reported grades for which mean scores are reported (i.e., the average grades in German, English, and Math). For all

other measures, sum scores are reported. a = Cronbachs alpha.

1384

J. Stoeber, A. Rambow / Personality and Individual Dierences 42 (2007) 13791389

and lower well-being, showing both more somatic complaints, t(117) = 2.67, p < .01 and more

depressive symptoms, t(117) = 2.04, p < .05 than male students. Consequently, we examined

whether the covariance matrices of the nine variables under study were equal for male and female

students using Boxs M test, which is highly sensitive to violations of homogeneity of covariance

(Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001). Because the test was nonsignicant with Boxs M = 44.40,

F(45, 306 664) < 1, data were collapsed across gender. Table 1 shows the sample means and standard deviations.

3. Results

First, the correlation of the two aspects of perfectionism was inspected. In line with previous

ndings (Stoeber et al., in press), striving for perfection showed a signicant correlation with negative reactions to imperfection, r = .65, p < .001, indicating that adolescent students who strive for

perfection at school tend to react negatively when they do not achieve perfect results. Moreover,

the high correlation suggested that, in addition to zero-order correlations, partial correlations

should be computed to control for the overlap between the two aspects of perfectionism (cf. Stoeber & Otto, 2006; Stoeber et al., in press). When correlations between perfectionism at school and

perceived parental pressure to be perfect were inspected, results showed that both aspects of perfectionism at school correlated with perceived parental pressure: striving for perfection with

r = .18, p < .05 and negative reactions to imperfection with r = .28, p < .01. However, when partial correlations were computed to control for the overlap between the two aspects of perfectionism, only negative reactions to imperfection still showed a signicant correlation with parental

pressure, pr = .22, p < .05, whereas striving for perfection did not, pr = .00, ns dovetailing with

previous ndings that parental pressure is more closely related to negative aspects of perfectionism than to positive aspects (Stober, 1998; Stumpf & Parker, 2000).

Next, zero-order correlations of perfectionism at school and perceived parental pressure with

motivation, achievement, and well-being were inspected (see Table 2). In line with expectations,

striving for perfection was related to hope of success, motivation for school, and higher achievement as indicated by higher grades in German, English, and Math. In contrast, negative reactions

to imperfection were related to fear of failure, depression, and somatic complaints; and perceived

parental pressure showed a signicant correlation with somatic complaints. Unexpectedly, negative reactions to imperfection were also related to higher grades. However, when partial correlations were computed to control for the overlap between striving for perfection and negative

reactions to imperfection, this correlation was reduced to near-zero (see Table 2). Furthermore,

striving for perfection showed an inverse correlation with depressive symptoms, when the inuence of negative reactions to imperfection was partialled out.

Finally, interaction eects of the two aspects of perfectionism at school on motivation, achievement, and well-being were explored by computing moderated regression analyses with interactions

between continuous predictors (see Aiken & West, 1991, chap. 2). These analyses found a significant interaction of striving for perfection and negative reactions to imperfection on depressive

symptoms, B = 0.08, SEB = 0.03, b = .23, p < .01. To understand the nature of this interaction,

regression graphs for values of 1 SD above and below the means of the two interacting variables

were plotted (see Aiken & West, 1991, pp. 1214 for details). The resulting graphs showed that the

J. Stoeber, A. Rambow / Personality and Individual Dierences 42 (2007) 13791389

1385

Table 2

Perfectionism at school and perceived parental pressure to be perfect: correlations

Measure

Perfectionism at school

Correlation

Motivation

Hope of success

Fear of failure

Motivation for school

Grades

Well-being

Somatic complaints

Depressive symptoms

Partial correlation

Striving for

perfection

Perceived parental

pressure

Striving for

perfection

Negative reactions

to imperfection

Negative reactions

to imperfection

.35***

.06

.41***

.37***

.12

.27**

.15

.21*

.35***

.16

.41***

.33***

.14

.31***

.16

.05

.08

.04

.03

.01

.06

.04

.22*

.38***

.11

.29**

.23*

.46***

.19*

.14

Note: N = 119121 adolescent school students, correlation = zero-order correlation, perceived parental pressure =

perceived parental pressure to be perfect, grades were reversed so that higher grades indicate higher achievement.

*

p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001, two-tailed.

negative correlation between striving for perfection and depressive symptoms was dependent on

students negative reactions to imperfection such that it was more pronounced in students with

lower levels of negative reactions to imperfection than in students with higher levels (see Fig. 1).

4. Discussion

Depressive Symptoms

The aim of the present research was to investigate further how perfectionism in adolescent

school students relates to motivation, achievement, and well-being, by examining two aspects

of perfectionism at school (striving for perfection, negative reactions to imperfection) and

22

20

18

16

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

Negative Reactions

to Imperfection

High

Low

Low

High

Striving for Perfection

Fig. 1. Interaction of striving for perfection and negative reactions to imperfection on depressive symptoms.

1386

J. Stoeber, A. Rambow / Personality and Individual Dierences 42 (2007) 13791389

perceived parental pressure to be perfect. As expected, striving for perfection was related to hope

of success and motivation for school whereas negative reactions to imperfection were related to

fear of failure, supporting Slade and Owenss (1998) dual process model of perfectionism which

states that positive perfectionism is associated with approach motivation (approach success)

and negative perfectionism with avoidance motivation (avoid failure). Moreover, striving for perfection was related to higher achievement as reected in higher grades in curricular core subjects.

While perceived parental pressure showed a signicant correlation with somatic complaints, corroborating previous ndings with college students (Hill et al., 2004), negative reactions to imperfection correlated with two indicators of low well-being, namely somatic complaints and

depressive symptoms. Regarding depressive symptoms, further analyses showed that striving

for perfection was inversely related to depressive symptoms in students once the inuence of negative reactions to imperfection was partialled out, and that the inverse correlation was more pronounced for students with lower levels of negative reactions to imperfection than for students with

higher levels. This nding indicates that adolescent students, who strive for perfection at school,

but do not get stressed, angry, or frustrated when results are not perfect, show higher well-being

than students, who do not strive for perfection, thus providing further support for the view that

perfectionistic strivingswith proper control of perfectionistic concernsare positive (Stoeber &

Otto, 2006; Stoeber et al., in press).

Some limitations apply, however. First, parental pressure to be perfect was measured only as

perceived by the adolescents. While perceived parental expectations and criticism are an important aspect of perfectionism (Frost et al., 1990), research has shown that adolescents perceptions

of parental rearing may show discrepancies with parental rearing as reported by the parents themselves (e.g., Paulson & Sputa, 1996). Consequently, future studies should include parents self-reports of expectations and criticism they have for their children and any perfectionistic aspirations

they have regarding their own parenting role (Snell, Overbey, & Brewer, 2005). Moreover, the

study was cross-sectional. Thus, it was not possible to determine which factors in the investigated

relationships represented antecedents and which consequences. This may be particularly important for the relationships between positive and negative aspects of perfectionism (striving for perfection, negative reactions to imperfection) and achievement motives (hope of success, fear of

failure) as it is unclear whether approach and avoidance achievement motives represent antecedents of positive and negative perfectionism or consequences (Slade & Owens, 1998). Future studies

should therefore employ longitudinal designs to allow for a causal analysis of the relationships.

Finally, the present study investigated only three aspects of perfectionismstriving for perfection,

negative reactions to imperfection, and perceived parental pressure to be perfectusing scales

originally developed for athletes, not students. While there is evidence that the perfectionism measures employed in the present study are valid measures of perfectionism when applied to school

and university students (Eismann, 2006; Stoeber & Kersting, in press), future studies should investigate whether the present ndings generalize to other aspects of perfectionism and also hold for

other measures of perfectionism than those employed in the present study.

Nonetheless, the present ndings have important implications as they provide further support

for the notion that striving for perfection should be considered a positive characteristic as it is,

more often than not, related to positive attributes and adaptive outcomes (Stoeber & Otto,

2006). Moreover, they provide support that this holds also for adolescent school students. Thus,

not all aspects of perfectionism are neurotic, unhealthy, or maladaptive. On the contrary, striving

J. Stoeber, A. Rambow / Personality and Individual Dierences 42 (2007) 13791389

1387

for perfection can form part of a healthy pursuit of excellence (Shafran, Cooper, & Fairburn,

2002) and may be adaptive in achievement situations where perfectionistic strivings could provide

students with additional motivation to do their best and thus achieve better grades. Parental pressure to be perfect and negative reactions to imperfection, however, are associated with the motivation to avoid failure and low well-being and thus may undermine healthy adolescent

development.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Franziska Reschke and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments and suggestions on earlier versions of this article.

Appendix

Perfectionism at school and perceived parental pressure to be perfect: items

Striving for perfection

At school, . . .

I strive to be as perfect as possible.

It is important to me to be perfect in everything I attempt.

I feel the need to be perfect.

I am a perfectionist as far as my targets are concerned.

I have the wish to do everything perfectly.

Negative reactions to imperfection

At school, . . .

I feel extremely stressed if everything doesnt go perfectly.

I feel depressed if I have not been perfect.

I get absolutely furious if I make mistakes.

I get frustrated if I do not fulll my high expectations.

I am dissatised with the whole school day if one class doesnt go perfectly.

Perceived parental pressure

My parents expect my performance to be perfect.

My parents criticize everything I do not do perfectly.

My parents are dissatised with me if my performance is not top class.

My parents expect me to be perfect.

My parents demand nothing less than perfection of me.

My parents make extremely high demands of me.

My parents set extremely high standards for me.

My parents are disappointed in me if my performance is not perfect.

1388

J. Stoeber, A. Rambow / Personality and Individual Dierences 42 (2007) 13791389

References

Accordino, D. B., Accordino, M. P., & Slaney, R. B. (2000). An investigation of perfectionism, mental health,

achievement, and achievement motivation in adolescents. Psychology in the Schools, 37, 535545.

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Atkinson, J. W. (1957). Motivational determinants of risk-taking behavior. Psychological Review, 64, 359372.

Bieling, P. J., Israeli, A., Smith, J., & Antony, M. M. (2003). Making the grade: the behavioral consequences of

perfectionism in the classroom. Personality and Individual Dierences, 35, 163178.

Dahme, G., Jungnickel, D., & Rathje, H. (1993). Guteeigenschaften der Achievement Motives Scale (AMS) von Gjesme

bersetzung von Gottert und Kuhl: Vergleich der Kennwerte norwegischer und

und Nygard (1970) in der deutschen U

deutscher Stichproben [Psychometric properties of a German translation of the Achievement Motives Scale (AMS):

comparison of results from Norwegian and German samples]. Diagnostica, 39, 257270.

Dunkley, D. M., Blankstein, K. R., Masheb, R. M., & Grilo, C. M. (2006). Personal standards and evaluative concerns

dimensions of clinical perfectionism: a reply to Shafran et al. (2002, 2003) and Hewitt et al. (2003). Behaviour

Research and Therapy, 44, 6384.

Dunn, J. G. H., Gotwals, J. K., & Dunn, J. C. (2005). An examination of the domain specicity of perfectionism among

intercollegiate student-athletes. Personality and Individual Dierences, 38, 14391448.

Einstein, D. A., Lovibond, P. F., & Gaston, J. E. (2000). Relationship between perfectionism and emotional symptoms

in an adolescent sample. Australian Journal of Psychology, 52, 8993.

Eismann, U. (2006). Perfektionismus und Motivation bei NachwuchsmusikerInnen [Perfectionism and motivation in

talented young musicians]. Unpublished diploma thesis, Department of Psychology, Martin Luther University of

Halle-Wittenberg, Germany.

Flett, G. L., & Hewitt, P. L. (2002). Perfectionism and maladjustment: an overview of theoretical, denitional, and

treatment issues. In G. L. Flett & P. L. Hewitt (Eds.), Perfectionism: Theory, research, and treatment (pp. 513).

Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Frost, R. O., Heimberg, R. G., Holt, C. S., Mattia, J. I., & Neubauer, A. L. (1993). A comparison of two measures of

perfectionism. Personality and Individual Dierences, 14, 119126.

Frost, R. O., & Henderson, K. J. (1991). Perfectionism and reactions to athletic competition. Journal of Sport and

Exercise Psychology, 13, 323335.

Frost, R. O., Marten, P., Lahart, C., & Rosenblate, R. (1990). The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognitive Therapy and

Research, 14, 449468.

Gjesme, T., & Nygard, R. (1970). Achievement-related motives: theoretical considerations and construction of a

measuring instrument. Unpublished manuscript, University of Oslo, Norway.

Grob, A., Luthi, R., Kaiser, F. G., Flammer, A., Mackinnon, A., & Wearing, A. J. (1991). Berner Fragebogen zum

Wohlbenden Jugendlicher (BFW) [The Bern Subjective Well-Being Questionnaire on Adolescents (BFW)].

Diagnostica, 37, 6675.

Grzegorek, J. L., Slaney, R. B., Franze, S., & Rice, K. G. (2004). Self-criticism, dependency, self-esteem, and grade

point average satisfaction among clusters of perfectionists and nonperfectionists. Journal of Counseling Psychology,

51, 192200.

Hamachek, D. E. (1978). Psychodynamics of normal and neurotic perfectionism. Psychology, 15, 2733.

Hautzinger, M., & Bailer, M. (1993). Allgemeine Depressions Skala (ADS) [General depression scale]. Weinheim,

Germany: Beltz-Testverlag.

Hewitt, P. L., & Flett, G. L. (1991). Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: conception, assessment, and

association with psychopathology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 456470.

Hill, R. W., Huelsmann, T. J., Furr, R. M., Kibler, J., Vicente, B. B., & Kennedy, C. (2004). A new measure of

perfectionism: The Perfectionism Inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment, 82, 8091.

Nounopoulos, A., Asbhy, J. S., & Gilman, R. (2006). Coping resources, perfectionism, and academic performance

among adolescents. Psychology in the Schools, 43, 613622.

Paulson, S. E., & Sputa, C. L. (1996). Patterns of parenting during adolescence: perceptions of adolescents and parents.

Adolescence, 31, 369381.

J. Stoeber, A. Rambow / Personality and Individual Dierences 42 (2007) 13791389

1389

Pomerantz, E. M., Altermatt, E. R., & Saxon, J. L. (2002). Making the grade but feeling distressed: gender dierences in

academic performance and internal distress. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94, 396404.

Radlo, L. S. (1977). The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied

Psychological Measurement, 1, 385401.

Rice, K. G., Ashby, J. S., & Slaney, R. B. (1998). Self-esteem as a mediator between perfectionism and depression: a

structural equation analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 45, 304314.

Rice, K. G., & Slaney, R. B. (2002). Clusters of perfectionists: two studies of emotional adjustment and academic

achievement. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 35, 3548.

Shafran, R., Cooper, Z., & Fairburn, C. G. (2002). Clinical perfectionism: a cognitive-behavioural analysis. Behaviour

Research and Therapy, 40, 773791.

Slade, P. D., & Owens, R. G. (1998). A dual process model of perfectionism based on reinforcement theory. Behavior

Modication, 22, 372390.

Slaney, R. B., Rice, K. G., Mobley, M., Trippi, J., & Ashby, J. S. (2001). The Revised Almost Perfect Scale.

Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 34, 130145.

Snell, W. E., Jr., Overbey, G. A., & Brewer, A. L. (2005). Parenting perfectionism and the parenting role. Personality

and Individual Dierences, 39, 613624.

Stober, J. (1998). The Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale: more perfect with four (instead of six) dimensions.

Personality and Individual Dierences, 24, 481491.

Stober, J. (2002). Motivation fur die Schule [Motivation for School]. In J. Stober (Ed.), Skalendokumentation

Personliche Ziele von SchulerInnen (Hallesche Berichte zur Padagogischen Psychologie No. 2, pp. 2021). Halle/

Saale, Germany: Martin Luther University of Halle, Department of Educational Psychology.

Stober, J., Otto, K., & Stoll, O. (2004). Mehrdimensionales Inventar zu Perfektionismus im Sport (MIPS)

[Multidimensional Inventory of Perfectionism in Sport (MIPS)]. In J. Stober, K. Otto, E. Pescheck, & O. Stoll

(Eds.), Skalendokumentation Perfektionismus im Sport (Hallesche Berichte zur Padagogischen Psychologie No. 7,

pp. 413). Halle/Saale, Germany: Martin Luther University of Halle, Department of Educational Psychology.

Stoeber, J., & Becker, C. (submitted for publication). Perfectionism, achievement motives, and attribution of success

and failure in female soccer players.

Stoeber, J., & Kersting, M. (in press). Perfectionism and aptitude test performance: testees who strive for perfection

achieve better test results. Personality and Individual Dierences. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.012.

Stoeber, J., & Otto, K. (2006). Positive conceptions of perfectionism: approaches, evidence, challenges. Personality and

Social Psychology Review, 10, 295319.

Stoeber, J., Otto, K., Pescheck, E., Becker, C., & Stoll, O. (in press). Perfectionism and competitive anxiety in athletes:

dierentiating striving for perfection and negative reactions to imperfection. Personality and Individual Dierences.

doi:10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.006.

Stoeber, J., Otto, K., & Stoll, O. (2005). Perfectionistic aspirations in athletes: except for the negative reactions, theyre

positive! Paper presented at the meeting of the Stress and Anxiety Research Society, Halle/Saale, Germany.

Stoeber, J., & Rennert, D. (2005). Perfectionism in school teachers: relations with job stress, burnout, and coping.

Poster presented at the meeting of the Stress and Anxiety Research Society, Halle/Saale, Germany.

Stumpf, H., & Parker, W. D. (2000). A hierarchical structural analysis of perfectionism and its relation to other

personality characteristics. Personality and Individual Dierences, 28, 837852.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2001). Using multivariate statistics (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Terry-Short, L. A., Owens, R. G., Slade, P. D., & Dewey, M. E. (1995). Positive and negative perfectionism. Personality

and Individual Dierences, 18, 663668.

Vandiver, B. J., & Worrell, F. C. (2002). The reliability and validity of scores on the Almost Perfect Scale-Revised with

academically talented middle school students. Journal of Secondary Gifted Education, 13, 108119.

Вам также может понравиться

- The Historical Background Interconnected Development and Integra PDFДокумент465 страницThe Historical Background Interconnected Development and Integra PDFLucian TomoiagăОценок пока нет

- Leroy MooreДокумент8 страницLeroy MooreRudika PuskasОценок пока нет

- 1888: The Message, The Mystery, and the MisconceptionsОт Everand1888: The Message, The Mystery, and the MisconceptionsРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- 1994 06 PDFДокумент28 страниц1994 06 PDFAurelian PopescuОценок пока нет

- What Is PerfectionismДокумент2 страницыWhat Is PerfectionismVictor Hugo ChoqueОценок пока нет

- The Destructiveness of Perfectionism Revisited Implications For TheДокумент17 страницThe Destructiveness of Perfectionism Revisited Implications For TheOmar Azaña VelezОценок пока нет

- Apocalypse Without God Apocalyptic ThougДокумент242 страницыApocalypse Without God Apocalyptic ThougJason KingОценок пока нет

- Is Perfectionism Good, Bad, or BothДокумент13 страницIs Perfectionism Good, Bad, or BothPolarisОценок пока нет

- Daniel 12:5-13 - Biblical Research InstituteДокумент2 страницыDaniel 12:5-13 - Biblical Research InstituteRonald Alejandro Aquije HerenciaОценок пока нет

- Christ Human Nature PositionДокумент2 страницыChrist Human Nature PositionJeneldon PontemayorОценок пока нет

- The Sanctuary and Its CleansingДокумент20 страницThe Sanctuary and Its CleansingThimóteo Stabenow HelkerОценок пока нет

- Secrets of The TabernacleДокумент83 страницыSecrets of The TabernacleTina SeguraОценок пока нет

- The Cosmic Controversy: World View For Theology and LifeДокумент43 страницыThe Cosmic Controversy: World View For Theology and LifeVictor Gerson DiazОценок пока нет

- Ministry Magazine December 1999Документ32 страницыMinistry Magazine December 1999Martinez YanОценок пока нет

- Perfectionism The Crucible of Giftedness-SILVERMANДокумент24 страницыPerfectionism The Crucible of Giftedness-SILVERMANsupabobby100% (1)

- Gerhard Hasel in SpectrumДокумент8 страницGerhard Hasel in SpectrumAlexander Carpenter100% (1)

- An Historicist Perspective On Daniel 11 Frank HardyДокумент341 страницаAn Historicist Perspective On Daniel 11 Frank HardyPedroОценок пока нет

- When The Best Is Not Enough: Features Cover StoryДокумент3 страницыWhen The Best Is Not Enough: Features Cover StoryNgoc Anh Nguyen ThiОценок пока нет

- Does God Exist PDF by Roger DicksonДокумент130 страницDoes God Exist PDF by Roger DicksonSolomon Adjei Marfo100% (2)

- Adventism and Biblical Perfection The DiДокумент14 страницAdventism and Biblical Perfection The DiRoberto MatosОценок пока нет

- Wesleyan and Quaker PerfectionismДокумент12 страницWesleyan and Quaker Perfectionismbbishop2059Оценок пока нет

- Auss 2007-V45-01 - B PDFДокумент164 страницыAuss 2007-V45-01 - B PDFJared Nun Barrenechea BacaОценок пока нет

- Usp - Assisted Reproduction - Germany & Europe PDFДокумент367 страницUsp - Assisted Reproduction - Germany & Europe PDFGeraldo RomanelloОценок пока нет

- Watchtower: God's Kingdom Rules! - 2014Документ234 страницыWatchtower: God's Kingdom Rules! - 2014sirjsslutОценок пока нет

- All My Online Friends Are Better Than Me Three Studies About Ability Based Comparative Social Media Use Self Esteem and Depressive TendenciesДокумент15 страницAll My Online Friends Are Better Than Me Three Studies About Ability Based Comparative Social Media Use Self Esteem and Depressive TendenciesFOLKLORE BRECHÓОценок пока нет

- Kellogg Alpha ApostasyДокумент39 страницKellogg Alpha ApostasyCésar MarroquínОценок пока нет

- UntitledДокумент142 страницыUntitledBilly B RuckusОценок пока нет

- 135Документ19 страниц135alfalfalfОценок пока нет

- The post-ascension mediatorial ministry of Christ - A study of the redemptive implications of the assertion that Christ’s mediation will climax in the cosmic judgment, Masters dissertation Craig BaxterДокумент65 страницThe post-ascension mediatorial ministry of Christ - A study of the redemptive implications of the assertion that Christ’s mediation will climax in the cosmic judgment, Masters dissertation Craig BaxterCraig BaxterОценок пока нет

- Meeting 02 Negotiation and Mediation Club v2 PDFДокумент11 страницMeeting 02 Negotiation and Mediation Club v2 PDFKantilal MalwaniaОценок пока нет

- An American Augustinian Sin and Salvation in The Dogmatic Theology of William G. T. SheddДокумент145 страницAn American Augustinian Sin and Salvation in The Dogmatic Theology of William G. T. SheddIveteCristãPaixãoОценок пока нет

- Subject Plus 2010 Synopsis ContentДокумент65 страницSubject Plus 2010 Synopsis ContentVenkateswara Rao SeoОценок пока нет

- Watchtower: Organized To Do Jehovah's Will, 2016Документ228 страницWatchtower: Organized To Do Jehovah's Will, 2016sirjsslutОценок пока нет

- Christian Worldview Paper IДокумент12 страницChristian Worldview Paper Idarlyn_n6660100% (1)

- Auss 2002 1001-V40-02 - BДокумент164 страницыAuss 2002 1001-V40-02 - BJared Nun Barrenechea BacaОценок пока нет

- Jon Paulien Sunday LawsДокумент19 страницJon Paulien Sunday LawsJosué RomeroОценок пока нет

- Revelation 4 & 5: The Judgement and The Seven SealsДокумент9 страницRevelation 4 & 5: The Judgement and The Seven Sealssolomob israelОценок пока нет

- Anne HuntДокумент13 страницAnne HuntstjeromesОценок пока нет

- 3 PolkinghorneДокумент9 страниц3 PolkinghorneJoaquim Filipe de CastroОценок пока нет

- 11 Moskala JudgmentДокумент25 страниц11 Moskala JudgmentigorbosnicОценок пока нет

- Vidal - 2008 What Is A WorldviewДокумент14 страницVidal - 2008 What Is A Worldviewbudi.handri100% (1)

- Creativity Understanding Man As The Imago Dei (Theology Thesis)Документ116 страницCreativity Understanding Man As The Imago Dei (Theology Thesis)Zdravko JovanovicОценок пока нет

- BRI Release 14 2Документ35 страницBRI Release 14 2oscarsmorbegosoОценок пока нет

- A Deconstruction of Social Diversity in The MediaДокумент6 страницA Deconstruction of Social Diversity in The MediaJa'Nyla ThompsonОценок пока нет

- Ministry Magazine June 2000Документ64 страницыMinistry Magazine June 2000Martinez YanОценок пока нет

- Bible Literalism and Constitutional OriginalismДокумент66 страницBible Literalism and Constitutional OriginalismBrian ShoafОценок пока нет

- Gullixson SermonДокумент44 страницыGullixson SermonRock ArtadiОценок пока нет

- Ellen G. White and Sola ScripturaДокумент14 страницEllen G. White and Sola ScripturaAfi Le Feu100% (1)

- UntitledДокумент10 страницUntitled1stLadyfreeОценок пока нет

- The Barley Overcomers: by Dr. Stephen E. Jones Chapter 1: Israel's Three FeastsДокумент39 страницThe Barley Overcomers: by Dr. Stephen E. Jones Chapter 1: Israel's Three FeastsKarina BagdasarovaОценок пока нет

- Early Church / Current Church On HomosexualityДокумент9 страницEarly Church / Current Church On Homosexualityrranshous100% (5)

- S4 Damian Et Al. 2016Документ13 страницS4 Damian Et Al. 2016Teodora AlexandrescuОценок пока нет

- Edd 1105 Final Research Paper AlaaДокумент17 страницEdd 1105 Final Research Paper Alaaapi-258233925Оценок пока нет

- Test Anxiety, Perfectionism, Goal Orientation, and Academic PerformanceДокумент13 страницTest Anxiety, Perfectionism, Goal Orientation, and Academic PerformanceMáthé AdriennОценок пока нет

- Procrastination, Self-Esteem, Academic Performance, and Well-Being: A Moderated Mediation ModelДокумент25 страницProcrastination, Self-Esteem, Academic Performance, and Well-Being: A Moderated Mediation ModelNatalia Silva100% (1)

- Chapter 1 - Introduction RationaleДокумент16 страницChapter 1 - Introduction RationaleTaurus SilverОценок пока нет

- Career-Decision Self-Efficacy Among College Students With SymptomДокумент8 страницCareer-Decision Self-Efficacy Among College Students With SymptommahmudОценок пока нет

- Research Proposal 2Документ47 страницResearch Proposal 2darsh jainОценок пока нет

- Pop Make-Emerald City OzДокумент3 страницыPop Make-Emerald City OzDana RoxanaОценок пока нет

- Patient Position PDFДокумент60 страницPatient Position PDFDana RoxanaОценок пока нет

- Pop Make ButterflyДокумент2 страницыPop Make ButterflyDana RoxanaОценок пока нет

- Popmake Unicorn PDFДокумент2 страницыPopmake Unicorn PDFDana RoxanaОценок пока нет

- Popmake Ship PDFДокумент3 страницыPopmake Ship PDFHeny AuliawatiОценок пока нет

- Popmake Unicorn PDFДокумент2 страницыPopmake Unicorn PDFDana RoxanaОценок пока нет

- Crawling and Walking Infants See The World Differently PDFДокумент16 страницCrawling and Walking Infants See The World Differently PDFAndreeaDianaDrăghiciОценок пока нет

- My Eid Coloring Book: Written and Illustrated by Cilia Ndiaye & Umm AhmadДокумент31 страницаMy Eid Coloring Book: Written and Illustrated by Cilia Ndiaye & Umm AhmadDana RoxanaОценок пока нет

- Sociologie Curs 10 2014Документ30 страницSociologie Curs 10 2014Dana RoxanaОценок пока нет

- Alchemy of Happiness by Imam AL-GhazaliДокумент1 027 страницAlchemy of Happiness by Imam AL-Ghazalikaibathelegacy87% (15)

- Anita ShreveДокумент121 страницаAnita ShreveDana RoxanaОценок пока нет

- M. Fatur - H1C018040 - PETROLOGIДокумент15 страницM. Fatur - H1C018040 - PETROLOGIFaturrachmanОценок пока нет

- Ug CR RPTSTDДокумент1 014 страницUg CR RPTSTDViji BanuОценок пока нет

- 145Kv Sf6 Circuit Breaker Type Ltb145D1/B List of Drawings: Description Document Reference NO. SRДокумент13 страниц145Kv Sf6 Circuit Breaker Type Ltb145D1/B List of Drawings: Description Document Reference NO. SRneeraj100% (1)

- Unit 07 Self-Test Chemistry Self TestДокумент2 страницыUnit 07 Self-Test Chemistry Self TestOluwatusin Ayo OluwatobiОценок пока нет

- Projector Spec 8040Документ1 страницаProjector Spec 8040Radient MushfikОценок пока нет

- Wavetek Portable RF Power Meter Model 1034A (1499-14166) Operating and Maintenance Manual, 1966.Документ64 страницыWavetek Portable RF Power Meter Model 1034A (1499-14166) Operating and Maintenance Manual, 1966.Bob Laughlin, KWØRLОценок пока нет

- Class - B Complementary Symmetry Power AmplifierДокумент3 страницыClass - B Complementary Symmetry Power AmplifierAnonymous SH0A20Оценок пока нет

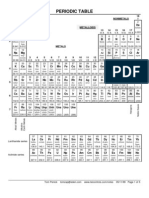

- Periodic Table and AtomsДокумент5 страницPeriodic Table and AtomsShoroff AliОценок пока нет

- Exercise 1 - Revision StringДокумент2 страницыExercise 1 - Revision StringKu H6Оценок пока нет

- Which Is The Best Solid Modelling - Dhyan AcademyДокумент3 страницыWhich Is The Best Solid Modelling - Dhyan Academydhyanacademy engineersОценок пока нет

- Product Specifications: Handheld Termination AidДокумент1 страницаProduct Specifications: Handheld Termination AidnormОценок пока нет

- Test ElectrolysisДокумент3 страницыTest ElectrolysisNatalia WhyteОценок пока нет

- Epson WorkForce Pro WF-C878-879RДокумент8 страницEpson WorkForce Pro WF-C878-879Rsales2 HARMONYSISTEMОценок пока нет

- Disc Brake System ReportДокумент20 страницDisc Brake System ReportGovindaram Rajesh100% (1)

- MODULAR QUIZ - 57 - Steel DesignДокумент9 страницMODULAR QUIZ - 57 - Steel DesignCornelio J. FernandezОценок пока нет

- K46 ManualДокумент8 страницK46 ManualDavid KasaiОценок пока нет

- Unit Exam 5Документ3 страницыUnit Exam 5Rose AstoОценок пока нет

- Incompressible Flow in Pipe Networks.Документ7 страницIncompressible Flow in Pipe Networks.Ayub Ali WehelieОценок пока нет

- Driver LCI 150W 500-850ma FlexC NF h28 EXC3 enДокумент7 страницDriver LCI 150W 500-850ma FlexC NF h28 EXC3 enMoustafa HelalyОценок пока нет

- Dover Artificial Lift - Hydraulic Lift Jet Pump BrochureДокумент8 страницDover Artificial Lift - Hydraulic Lift Jet Pump BrochurePedro Antonio Mejia Suarez100% (1)

- Practice Question ElectricityДокумент3 страницыPractice Question ElectricityIvan SetyawanОценок пока нет

- KVS - Regional Office, JAIPUR - Session 2021-22Документ24 страницыKVS - Regional Office, JAIPUR - Session 2021-22ABDUL RAHMAN 11BОценок пока нет

- Week 1 Lesson 1 2nd QuarterДокумент2 страницыWeek 1 Lesson 1 2nd QuarterKristine Jewel MacatiagОценок пока нет

- Fiberglass Fire Endurance Testing - 1992Документ58 страницFiberglass Fire Endurance Testing - 1992shafeeqm3086Оценок пока нет

- The Library of Babel - WikipediaДокумент35 страницThe Library of Babel - WikipediaNeethu JosephОценок пока нет

- HANA OverviewДокумент69 страницHANA OverviewSelva KumarОценок пока нет

- GMS60CSДокумент6 страницGMS60CSAustinОценок пока нет

- Rotational Dynamics-07-Problems LevelДокумент2 страницыRotational Dynamics-07-Problems LevelRaju SinghОценок пока нет

- Introduction To Java Programming ReviewerДокумент90 страницIntroduction To Java Programming ReviewerJohn Ryan FranciscoОценок пока нет