Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

GMA v. Pabriga (2013)

Загружено:

Nap GonzalesАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

GMA v. Pabriga (2013)

Загружено:

Nap GonzalesАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

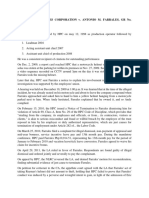

GMA NETWORK, INC., petitioner, v. CARLOS P. PABRIGA, GEOFFREY F. ARIAS, KIRBY N. CAMPO, ARNOLD L.

LAGAHIT, and ARMANDO A. CATUBIG, respondents

G.R. No. 176419, November 27, 2013, J. Leonardo-de Castro

FACTS:

Respondents are television technicians assigned to the following tasks:

o Manning of Technical Operations Center

o Acting as Transmitter/VTR men

o Acting as Maintenance staff

o Acting as cameramen

On July 19, 1999 due to the miserable working conditions private respondents, television technicians, were forced

to file a complaint against GMA before the NLRC Regional Arbitration Branch No. VII Cebu City. On August 4,

1999, GMA received a notice of hearing of the complaint. The following day, petitioners Engineering Manager,

Roy Villacastin, confronted the private respondents about said complaint.

On August 9, 1999, private respondents were summoned to the office of GMAs Area Manager, Mrs. Susan Alino,

and they were made to explain why they filed the complaint. The next day, private respondents were barred from

entering and reporting for work without any notice stating the reasons therefor.

On August 13, 1999, private respondents, through their counsel, wrote a letter to Alino, requesting that they be

recalled back to work

On August 23, 1999, a reply from Mr. Bienvenido Bustria, GMAs head of Personal and Labor Relations Division,

admitted the non-payment of benefits but did not mention the request of private respondents to be allowed to

return to work. On 15 September 1999, private respondents sent another letter to Mr. Bustria reiterating their

request to work but the same was totally ignored. On 8 October 1999, private respondents filed an amended

complaint raising the following additional issues: 1) Unfair Labor Practice; 2) Illegal dismissal; and 3) Damages

and Attorneys fees.

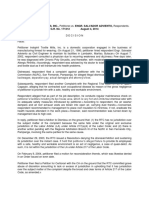

On 23 September 1999, a mandatory conference was set to amicably settle the dispute between the parties,

however, the same proved to be futile. As a result, both of them were directed to file their respective position

papers. On 10 November 1999, private respondents filed their position paper and on 2 March 2000, they received

a copy of petitioners position paper. The following day, the Labor Arbiter issued an order considering the case

submitted for decision.

th

LA dismissed the complaint for illegal dismissal and unfair labor practice, but held petitioner liable for 13 month

pay. Respondents appealed to NLRC. NLRC reversed LA, saying a) All complainants are regular employees

with respect to the particular activity to which they were assigned, until it ceased to exist. As such, they are

entitled to payment of separation pay computed at one (1) month salary for every year of service; b) They are not

entitled to overtime pay and holiday pay; and c) They are entitled to 13th month pay, night shift differential and

service incentive leave pay. For purposes of accurate computation, the entire records are REMANDED to the

Regional Arbitration Branch of origin which is hereby directed to require from respondent the production of

additional documents where necessary.

ISSUE:

WON respondents are regular employees and not project employees

WON the requisites of a valid fixed term employment are met

HELD:

1.

The principal test for determining whether particular employees are properly characterized as "project employees"

as distinguished from "regular employees," is whether or not the "project employees" were assigned to carry out a

"specific project or undertaking," the duration (and scope) of which were specified at the time the employees were

engaged for that project.

Employers claiming that their workers are project employees should not only prove that the duration and scope of

the employment was specified at the time they were engaged, but also that there was indeed a project. The

project could either be (1) a particular job or undertaking that is within the regular or usual business of the

employer company, but which is distinct and separate, and identifiable as such, from the other undertakings of the

company; or (2) a particular job or undertaking that is not within the regular business of the corporation.

In the case at bar, respondents jobs and undertakings are clearly within the regular or usual business of GMA,

and are not identifiably distinct or separate from the other undertakings of the company.

Petitioners allegation that respondents were merely substitutes or what they call pinch-hitters (which means that

they were employed to take the place of regular employees of petitioner who were absent or on leave) does not

change the fact that their jobs cannot be considered projects within the purview of the law. Every industry, even

public offices, has to deal with securing substitutes for employees who are absent or on leave. Such tasks,

whether performed by the usual employee or by a substitute, cannot be considered separate and distinct from the

other undertakings of the company. While it is managements prerogative to device a method to deal with this

issue, such prerogative is not absolute and is limited to systems wherein employees are not ingeniously and

methodically deprived of their constitutionally protected right to security of tenure. We are not convinced that a big

corporation such as petitioner cannot device a system wherein a sufficient number of technicians can be hired

with a regular status who can take over when their colleagues are absent or on leave, especially when it appears

from the records that petitioner hires so-called pinch-hitters regularly every month.

Nowhere in the records is there any showing that petitioner reported the completion of its projects and the

dismissal of private respondents in its finished projects to the nearest Public Employment Office as per Policy

Instruction No. 2015 of the Department of Labor and Employment [DOLE]. Jurisprudence abounds with the

consistent rule that the failure of an employer to report to the nearest Public Employment Office the termination of

its workers services everytime a project or a phase thereof is completed indicates that said workers are not

project employees.

A project employee may also attain the status of a regular employee if there is a continuous rehiring of project

employees after the stoppage of a project; and the activities performed are usual [and] customary to the business

or trade of the employer. The circumstances set forth by law and jurisprudence is present in this case. Even if

private respondents are to be considered as project employees, they attained regular employment status, just the

same.

2.

The decisive determinant in fixed-term employment is not the activity that the employee is called upon to perform

but the day certain agreed upon by the parties for the commencement and termination of the employment

relationship. Cognizant of the possibility of abuse in the utilization of fixed-term employment contracts, we

emphasized that where from the circumstances it is apparent that the periods have been imposed to preclude

acquisition of tenurial security by the employee, they should be struck down as contrary to public policy or morals.

We thus laid down indications or criteria under which "term employment" cannot be said to be in circumvention of

the law on security of tenure, namely:

o 1) The fixed period of employment was knowingly and voluntarily agreed upon by the parties without any

force, duress, or improper pressure being brought to bear upon the employee and absent any other

circumstances vitiating his consent; or

o 2) It satisfactorily appears that the employer and the employee dealt with each other on more or less

equal terms with no moral dominance exercised by the former or the latter

It could not be supposed that private respondents KNOWINGLY and VOLUNTARILY agreed to the 5-month

employment contract. Cannery workers are never on equal terms with their employers. Almost always, they agree

to any terms of an employment contract just to get employed considering that it is difficult to find work given their

ordinary qualifications. Their freedom to contract is empty and hollow because theirs is the freedom to starve if

they refuse to work as casual or contractual workers. Indeed, to the unemployed, security of tenure has no value.

It could not then be said that petitioner and private respondents "dealt with each other on more or less equal

terms with no moral dominance whatever being exercised by the former over the latter.

Similarly, in the case at bar, we find it unjustifiable to allow petitioner to hire and rehire workers on fixed terms, ad

infinitum, depending upon its needs, never attaining regular employment status. To recall, respondents were

repeatedly rehired in several fixed term contracts from 1996 to 1999.

Respondents are regular employees of petitioner. As regular employees, they are entitled to security of tenure

and therefore their services may be terminated only for just or authorized causes. Since petitioner failed to prove

any just or authorized cause for their termination, we are constrained to affirm the findings of the NLRC and the

Court of Appeals that they were illegally dismissed. Respondents entitled to separation pay, night shift

differentials.

Вам также может понравиться

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorДокумент15 страниц6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Sample SPAДокумент3 страницыSample SPAiamyni96% (26)

- Rose ExhibitsДокумент226 страницRose ExhibitsEriq GardnerОценок пока нет

- DMV Duplicate Title ApplicationДокумент2 страницыDMV Duplicate Title Applicationfoufou79100% (1)

- Labor Case: Meal Allowances and Minimum WageДокумент1 страницаLabor Case: Meal Allowances and Minimum WageAngelRea50% (2)

- Family driver's rights governed by Civil CodeДокумент3 страницыFamily driver's rights governed by Civil CodeJanex TolineroОценок пока нет

- Yu VS NLRCДокумент2 страницыYu VS NLRCNap GonzalesОценок пока нет

- Sop PsurДокумент8 страницSop PsurGehan El Hefney100% (1)

- Manila Fashions v. NLRC ruling on void CBA wage condonation provisionДокумент2 страницыManila Fashions v. NLRC ruling on void CBA wage condonation provisionNap Gonzales100% (1)

- ER-EE Relationship in Yamaha Mechanic CaseДокумент2 страницыER-EE Relationship in Yamaha Mechanic CaseKrizzia GojarОценок пока нет

- Atlanta Industries vs. Sebolino: Illegal Dismissal of Employees Ruled by CourtДокумент3 страницыAtlanta Industries vs. Sebolino: Illegal Dismissal of Employees Ruled by CourtJoe RealОценок пока нет

- Manila Water vs. PenaДокумент3 страницыManila Water vs. Penalleiryc7Оценок пока нет

- GMA Network v PabrigaДокумент48 страницGMA Network v PabrigaReino CabitacОценок пока нет

- Manila Water Co. v. Pena DigestДокумент2 страницыManila Water Co. v. Pena DigestBetson Cajayon100% (1)

- A. Nate Casket Maker vs. Arango - DigestДокумент2 страницыA. Nate Casket Maker vs. Arango - DigestBigs BeguiaОценок пока нет

- Engineering and Machinery CorpДокумент1 страницаEngineering and Machinery CorpkeithnavaltaОценок пока нет

- Afp Vs NLRCДокумент2 страницыAfp Vs NLRCRyan AnatanОценок пока нет

- Labor - Employment DigestДокумент12 страницLabor - Employment DigestMilcah Mae PascualОценок пока нет

- Linco vs. LacebalДокумент2 страницыLinco vs. LacebalVincent Quiña PigaОценок пока нет

- Villamaria v. Court of AppealsДокумент2 страницыVillamaria v. Court of Appealsapbuera100% (1)

- Republic v. Sese (2014)Документ2 страницыRepublic v. Sese (2014)Nap Gonzales100% (1)

- PBCOM Vs NLRCДокумент3 страницыPBCOM Vs NLRCmamp05100% (1)

- ABS CBN Vs NazarenoДокумент9 страницABS CBN Vs NazarenoJohn Ayson67% (3)

- Cosmopolitan Funeral Homes vs. Noli Maalat and NLRC, G.R. No. 86693, 187 SCRA 108, July 2, 1990.Документ2 страницыCosmopolitan Funeral Homes vs. Noli Maalat and NLRC, G.R. No. 86693, 187 SCRA 108, July 2, 1990.Lizzy LiezelОценок пока нет

- Digest Orozco V CAДокумент2 страницыDigest Orozco V CAMRОценок пока нет

- De Ocampo, JR vs. NLRCДокумент3 страницыDe Ocampo, JR vs. NLRCBalaod MaricorОценок пока нет

- Basan Vs Coca Cola BottlersДокумент3 страницыBasan Vs Coca Cola BottlersJereca Ubando JubaОценок пока нет

- Hanjin V IbanezДокумент2 страницыHanjin V IbanezJoshua Pielago100% (1)

- Whether Building Care Corporation is an independent contractorДокумент2 страницыWhether Building Care Corporation is an independent contractorPatrick Chad Guzman33% (6)

- Case Digests Labor StandardsДокумент3 страницыCase Digests Labor StandardsAxel GonzalezОценок пока нет

- Dissolution PlanДокумент4 страницыDissolution PlanAnonymous IuZaAWAWОценок пока нет

- Gonzales vs. NLRCДокумент2 страницыGonzales vs. NLRCDiane ヂエン100% (1)

- Sison v. ComelecДокумент2 страницыSison v. ComelecMyrahОценок пока нет

- Makati Haberdashery Vs NLRCДокумент2 страницыMakati Haberdashery Vs NLRCIda Chua67% (3)

- Widow Entitled to Equal Share of Inactive Partnership ProfitsДокумент2 страницыWidow Entitled to Equal Share of Inactive Partnership ProfitsNap GonzalesОценок пока нет

- SEO-Optimized Title for Partnership Dissolution CaseДокумент2 страницыSEO-Optimized Title for Partnership Dissolution CaseNap GonzalesОценок пока нет

- CA Ruling on TV Newscaster's Employment Status ReversedДокумент7 страницCA Ruling on TV Newscaster's Employment Status ReversedMaya Julieta Catacutan-EstabilloОценок пока нет

- Casket Makers Liable for Illegal DismissalДокумент2 страницыCasket Makers Liable for Illegal DismissalIldefonso HernaezОценок пока нет

- Mactan Workers Union v. AboitizДокумент1 страницаMactan Workers Union v. AboitizNap GonzalesОценок пока нет

- Marketing Director Contract DisputeДокумент2 страницыMarketing Director Contract DisputeClyde Tan0% (2)

- PCI AUTOMATION CENTER, INC. vs. NLRCДокумент3 страницыPCI AUTOMATION CENTER, INC. vs. NLRCJomarco SantosОценок пока нет

- Teotico vs. Del ValДокумент2 страницыTeotico vs. Del ValNap GonzalesОценок пока нет

- Hocheng Philippines Corporation V. Antonio M. Farrales, GR No. 211497, 2015-03-18 FactsДокумент2 страницыHocheng Philippines Corporation V. Antonio M. Farrales, GR No. 211497, 2015-03-18 FactsTiff Dizon100% (1)

- Manila Memorial Park Vs Ezard LluzДокумент4 страницыManila Memorial Park Vs Ezard LluzJMAОценок пока нет

- SC Rules Against Circumvention of Employee TenureДокумент3 страницыSC Rules Against Circumvention of Employee TenureJose Antonio Barroso67% (3)

- 86) Phil Graphic Arts Vs NLRC DigestedДокумент2 страницы86) Phil Graphic Arts Vs NLRC DigestedAnonymous Xkzaifvd100% (3)

- Philippine Bank vs. NLRC Case DigestДокумент1 страницаPhilippine Bank vs. NLRC Case Digestunbeatable38Оценок пока нет

- Protecting Women and Children from Violence ActДокумент58 страницProtecting Women and Children from Violence ActMoon Beams100% (7)

- San Miguel Corporation Vs MaercДокумент1 страницаSan Miguel Corporation Vs MaercMacОценок пока нет

- Mercado vs. NLRCДокумент1 страницаMercado vs. NLRCElla ThoОценок пока нет

- Brent School Vs ZamoraДокумент2 страницыBrent School Vs ZamoraJanelle Manzano100% (4)

- Insular Life Assurance Co. vs NLRCДокумент2 страницыInsular Life Assurance Co. vs NLRCAnna Bea Datu Geronga100% (1)

- Semblante Et Al. vs. Court of Appeals, Et AДокумент1 страницаSemblante Et Al. vs. Court of Appeals, Et ARosana Villordon SoliteОценок пока нет

- Sonza V ABSCBN Case DigestДокумент4 страницыSonza V ABSCBN Case DigestYsabel Padilla89% (9)

- Indophil Textile Mills, Inc. vs. Salvador Adviento, G.R. No. 171212, August 4, 2014Документ3 страницыIndophil Textile Mills, Inc. vs. Salvador Adviento, G.R. No. 171212, August 4, 2014MJ AroОценок пока нет

- Insurance Agent DisputeДокумент2 страницыInsurance Agent DisputeAnonymous 5MiN6I78I0Оценок пока нет

- Rodelas v. Aranza (1982)Документ2 страницыRodelas v. Aranza (1982)Nap GonzalesОценок пока нет

- 25 - PURE FOODS CORPORATION Vs NLRC Case DigestДокумент2 страницы25 - PURE FOODS CORPORATION Vs NLRC Case DigestKornessa ParasОценок пока нет

- AFP Retirement and Separation Benefits System v. RepublicДокумент2 страницыAFP Retirement and Separation Benefits System v. RepublicNap GonzalesОценок пока нет

- Royal Homes Marketing Corp vs. AlcantaraДокумент3 страницыRoyal Homes Marketing Corp vs. AlcantaraEula Parawan50% (2)

- Legend Hotel Case DigestДокумент2 страницыLegend Hotel Case DigestKian Fajardo100% (1)

- Holiday Inn V NLRCДокумент3 страницыHoliday Inn V NLRCBreth1979100% (1)

- San Miguel Vs Aballa (2005) G.R. 149011 DigestДокумент2 страницыSan Miguel Vs Aballa (2005) G.R. 149011 DigestBetson Cajayon100% (1)

- Century Properties Inc. vs. Babiano2016Документ3 страницыCentury Properties Inc. vs. Babiano2016Andrea TiuОценок пока нет

- GMA V PabrigaДокумент3 страницыGMA V PabrigaEmmanuel Ortega100% (1)

- CD - Gapayao v. Fulo, SSSДокумент2 страницыCD - Gapayao v. Fulo, SSSJane SudarioОценок пока нет

- Labor Congress of The Phil vs. NLRCДокумент1 страницаLabor Congress of The Phil vs. NLRCEarl Tan100% (2)

- 02 Maraguinot V NLRCДокумент2 страницы02 Maraguinot V NLRCPlaneteer Prana100% (3)

- Answers To The Questions in The Course Guide Personal Insurance Ains 22 2 Edition 2015-2016Документ5 страницAnswers To The Questions in The Course Guide Personal Insurance Ains 22 2 Edition 2015-2016Rakshit Shah0% (1)

- 003 - Kinds of Employees - Gma Network V Pabriga - DigestДокумент2 страницы003 - Kinds of Employees - Gma Network V Pabriga - DigestKate GaroОценок пока нет

- Banco Atlantico v. Auditor GeneralДокумент1 страницаBanco Atlantico v. Auditor GeneralNap GonzalesОценок пока нет

- Integrated Contractor and Plumbing Works, Inc. vs. NLRC and Glen SolonДокумент2 страницыIntegrated Contractor and Plumbing Works, Inc. vs. NLRC and Glen SolonAtheena Marie PalomariaОценок пока нет

- Villareal V RamirezДокумент2 страницыVillareal V RamirezNap GonzalesОценок пока нет

- Canque Vs CAДокумент3 страницыCanque Vs CANap GonzalesОценок пока нет

- Filipinas Synthetic Fiber Corporation vs. NLRC, Et Al.Документ2 страницыFilipinas Synthetic Fiber Corporation vs. NLRC, Et Al.heinnahОценок пока нет

- Atok Big Wedge Company Vs GisonДокумент1 страницаAtok Big Wedge Company Vs Gisonsescuzar100% (1)

- Century Properties, Inc. Vs Edwin J. Babiano and Emma B. Concepcion, 795 SCRA 671, G.R. No. 220978 (July 05, 2016)Документ2 страницыCentury Properties, Inc. Vs Edwin J. Babiano and Emma B. Concepcion, 795 SCRA 671, G.R. No. 220978 (July 05, 2016)Lu CasОценок пока нет

- Marites Bernardo Et Al Vs NLRCДокумент2 страницыMarites Bernardo Et Al Vs NLRCEdu RiparipОценок пока нет

- Rural Bank vs Julve Case on Constructive DismissalДокумент2 страницыRural Bank vs Julve Case on Constructive DismissalKornessa ParasОценок пока нет

- Eceta Vs EcetaДокумент2 страницыEceta Vs EcetaIvan Montealegre ConchasОценок пока нет

- NLRC Ruling on Solidary Liability OverturnedДокумент2 страницыNLRC Ruling on Solidary Liability OverturnedMaden AgustinОценок пока нет

- NLRC Ruling on Project Employees AffirmedДокумент3 страницыNLRC Ruling on Project Employees AffirmedJackie Canlas100% (1)

- Bentir vs. LeandaДокумент1 страницаBentir vs. LeandaDanica CaballesОценок пока нет

- Beta Electric Corp To ALU-TUCPДокумент7 страницBeta Electric Corp To ALU-TUCPNN DDLОценок пока нет

- University of Pangasinan Faculty Union Vs University of PangasinanДокумент2 страницыUniversity of Pangasinan Faculty Union Vs University of PangasinanDeriq DavidОценок пока нет

- GMA NETWORK, INC., Petitioner, vs. CARLOS P. Pabriga, Geoffrey F. Arias, Kirby N. Campo, Arnold L. Lagahit and Armand A. Catubig, RespondentsДокумент23 страницыGMA NETWORK, INC., Petitioner, vs. CARLOS P. Pabriga, Geoffrey F. Arias, Kirby N. Campo, Arnold L. Lagahit and Armand A. Catubig, RespondentsSheba AranconОценок пока нет

- PHPPДокумент1 страницаPHPPNap GonzalesОценок пока нет

- PHPPДокумент1 страницаPHPPNap GonzalesОценок пока нет

- Russell Costume BadgesДокумент4 страницыRussell Costume BadgesNap Gonzales100% (1)

- 2020 - 2021 Philippine Fulbright Graduate Student Program: Fields of StudyДокумент11 страниц2020 - 2021 Philippine Fulbright Graduate Student Program: Fields of StudyNap GonzalesОценок пока нет

- Republic vs East Silver LaneДокумент4 страницыRepublic vs East Silver LaneNap GonzalesОценок пока нет

- Asdfghkjh VVJ V VHJ V JVJДокумент1 страницаAsdfghkjh VVJ V VHJ V JVJNap GonzalesОценок пока нет

- Berlin Sans MsДокумент2 страницыBerlin Sans MsNap GonzalesОценок пока нет

- 2019 2020 Application For TheДокумент13 страниц2019 2020 Application For TheNap GonzalesОценок пока нет

- AsdfasdadДокумент1 страницаAsdfasdadNap GonzalesОценок пока нет

- Civil LawДокумент8 страницCivil LawGorgeousEОценок пока нет

- Agulto v. CAДокумент1 страницаAgulto v. CANap GonzalesОценок пока нет

- Exec. Order 2009 - The Family CodeДокумент59 страницExec. Order 2009 - The Family CodeEj OrqueОценок пока нет

- Binay v. Domingo (1991)Документ3 страницыBinay v. Domingo (1991)Nap GonzalesОценок пока нет

- Samson v. RestriveraДокумент5 страницSamson v. RestriveraNap GonzalesОценок пока нет

- Philippine Realty v Ley Construction | Sereno Rules on Validity of Price Escalation AgreementДокумент2 страницыPhilippine Realty v Ley Construction | Sereno Rules on Validity of Price Escalation AgreementNap GonzalesОценок пока нет

- Lemay Bank Partnership Dissolution NoticeДокумент2 страницыLemay Bank Partnership Dissolution NoticeNap GonzalesОценок пока нет

- Partnership Dissolution Case Remanded for Proper AccountingДокумент2 страницыPartnership Dissolution Case Remanded for Proper AccountingNap GonzalesОценок пока нет

- Fraley v. Facebook, Inc, Original ComplaintДокумент22 страницыFraley v. Facebook, Inc, Original ComplaintjonathanjaffeОценок пока нет

- GSIS LEGAL FEE EXEMPTION DENIEDДокумент9 страницGSIS LEGAL FEE EXEMPTION DENIEDAlicia Jane NavarroОценок пока нет

- (PDF) Trial of Warrant Cases - CompressДокумент10 страниц(PDF) Trial of Warrant Cases - CompressgunnuОценок пока нет

- Republic Act No. 9775 (#1)Документ6 страницRepublic Act No. 9775 (#1)Marc Jalen ReladorОценок пока нет

- Goquiolay vs. Sycip, G.R. No. L-11840, December 10, 1963Документ7 страницGoquiolay vs. Sycip, G.R. No. L-11840, December 10, 1963Lou Ann AncaoОценок пока нет

- Sec. 1601 To 1618 of NCCДокумент3 страницыSec. 1601 To 1618 of NCCGuiller C. MagsumbolОценок пока нет

- New Skilled Regional Visa RegsДокумент56 страницNew Skilled Regional Visa RegsarunОценок пока нет

- Presidential Decree No. 49 S. 1972Документ15 страницPresidential Decree No. 49 S. 1972gabОценок пока нет

- Heirs of Reyes Vs MijaresДокумент2 страницыHeirs of Reyes Vs MijaresphgmbОценок пока нет

- 10 National Steel Corporation vs. CA, 283 SCRA 45Документ35 страниц10 National Steel Corporation vs. CA, 283 SCRA 45blessaraynesОценок пока нет

- Recanting Witness Leads to New Trial in Murder CaseДокумент10 страницRecanting Witness Leads to New Trial in Murder CaseAdrianne Benigno100% (1)

- Capitol Subdivision, Inc. OF Negros Occidental: Plaintiff-Appellant Defendant-AppelleeДокумент9 страницCapitol Subdivision, Inc. OF Negros Occidental: Plaintiff-Appellant Defendant-AppelleeCentSeringОценок пока нет

- Ordinance Grace Marks Passing Subjects ExamsДокумент2 страницыOrdinance Grace Marks Passing Subjects ExamsNAGAR CARTОценок пока нет

- Small Business Presentation For HAULДокумент23 страницыSmall Business Presentation For HAULErin McClartyОценок пока нет

- Westley Brian Cani v. United States, 331 F.3d 1210, 11th Cir. (2003)Документ6 страницWestley Brian Cani v. United States, 331 F.3d 1210, 11th Cir. (2003)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Lukban V Optimum Development Bank (Mortgage-Rghts and Obligation)Документ2 страницыLukban V Optimum Development Bank (Mortgage-Rghts and Obligation)Robert RosalesОценок пока нет

- Milaor - Adickes V SH KressДокумент4 страницыMilaor - Adickes V SH KressAndrea MilaorОценок пока нет