Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

HP Jan05 Bleed

Загружено:

Syahanim IsmailОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

HP Jan05 Bleed

Загружено:

Syahanim IsmailАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Review of Clinical Signs

Series Editor: Bernard M. Karnath, MD

Easy Bruising and Bleeding in the Adult

Patient: A Sign of Underlying Disease

Bernard M. Karnath, MD

chief complaint of easy bruising and bleeding

should alert the clinician to the possibility of a

serious underlying disease process. The evaluation includes a careful history and a complete physical examination. As many bleeding disorders are inherited, a detailed family history should also

be obtained. Laboratory investigations should be guided by the clinical impression.

In general, easy bruising is associated with platelet

disorders, whereas easy bleeding is associated with

coagulation disorders. There is significant overlap,

however, and platelet and coagulation disorders may

coexist. Platelet disorders as well as coagulation abnormalities must be considered in any patient with bruising or bleeding that is disproportionate to the offending trauma (Table 1).1 Common complaints associated

with platelet and coagulation disorders include epistaxis, gingival bleeding, menorrhagia, gastrointestinal

bleeding, ecchymosis, purpura, and petechia. Physical

abuse is always a consideration but must not be assumed.2 This article reviews the approach to evaluating

patients who present with easy bruising or bleeding.

Two illustrative cases are presented.

The definitions of petechia, purpura, and ecchymosis differ among sources, but the definitions used here

are as follows: Ecchymoses are large areas of bruising that

occur out of proportion to the offending trauma.

Petechiae are pinpoint (13 mm), nonraised, reddish

purple lesions that result from intradermal or submucous hemorrhage. Purpura are larger (> 3 mm) red to

purple nonblanching lesions that also result from

bleeding into the skin and mucous membranes.

Unlike bruising, petechiae and purpura do not result

from trauma.

APPROACH TO THE PATIENT WITH EASY BRUISING

Bruises are large areas of subcutaneous bleeding.

Bruising is considered abnormal if it is out of proportion to the offending trauma. Not all patients with easy

bruising have a serious underlying disorder, however.

www.turner-white.com

SIGNSEASY BRUISING AND BLEEDING

Easy bruising

Ecchymoses

Purpura

Petechiae

Easy bleeding

Epistaxis

Gastrointestinal/rectal bleeding

Gingival bleeding

Hemarthrosis

Hematuria

Menorrhagia

Prolonged bleeding during surgery/tooth extraction

Senile purpura, seen in elderly patients, is a benign

process caused by capillary fragility associated with

weakened connective tissue and is not a sign of a serious underlying disease. In addition, certain medications, such as aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory

drugs (NSAIDs), corticosteroids, and anticoagulants

may be associated with purpura. Bruising restricted to

the lower limbs is usually normal. (This is not always

true, however, as illustrated in the case presented.)

Easy bruising over the trunk, neck, and face warrant

further hematologic evaluation.3 Although easy bruising is more commonly associated with thrombocytopenia, coexistence with coagulation disorders is common.

Clinical Evaluation

The history should focus on the onset of easy bruising as well as a family history of hematologic disorders.

A detailed history of medication use is critical. The

Dr. Karnath is an associate professor of internal medicine, University of

Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, Galveston, TX.

Hospital Physician January 2005

35

Karnath : Easy Bruising and Bleeding : pp. 35 39

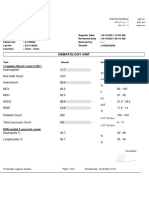

Table 1. Clues to the Diagnosis of Easy Bruising and Easy Bleeding

Finding

Easy bruising

Possible Cause

History

Bruising out of proportion to the offending trauma

Platelet disorder

Advanced age

Senile purpura

Family history of easy bruising

Qualitative platelet disorder

Medication use (eg, heparin, warfarin, aspirin, steroids, NSAIDs)

Platelet inhibition, coagulopathy

Physical examination

Easy bleeding

Multiple bruises, petechiae

Severe thrombocytopenia

Lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly

Hematologic malignancy

History

Prolonged bleeding from minimal trauma (eg, minor surgery, tooth

extractions)

Coagulation disorder and/or platelet disorder

Menorrhagia, spontaneous bleeding (eg, epistaxis, hemarthrosis,

hematuria, rectal bleeding)

Coagulation disorder and/or platelet disorder

Family history of easy bleeding

Hemophilia, qualitative platelet disorder

Medications (eg, heparin, warfarin, aspirin, steroids, NSAIDs)

Platelet inhibition, coagulopathy

Physical examination

Hemarthrosis

Hemophilia

Spider angiomata, scleral icterus, ascites, gynecomastia

Chronic liver disease

NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

physical examination is essential in elucidating an

underlying cause. Take note of which areas are

bruised. Bruises on the lower extremities are not considered quite as abnormal as bruising elsewhere, but

petechiae, which are typically seen on the lower extremities, are a sign of severe thrombocytopenia. Evidence of hematologic malignancy should be sought,

including lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly. Laboratory investigations should include a complete blood

count, platelet count, prothrombin time (PT), and partial thromboplastin time (PTT). Hematologic malignancy may be uncovered with a complete blood count

with peripheral smear.

mune disorders (including immune thrombocytopenic purpura).

Qualitative platelet disorders can be either congenital or acquired.4,5 Patients with qualitative platelet disorders have prolonged bleeding times despite a normal platelet count. A family history is important in

evaluating a patient with a qualitative platelet disorder.

Congenital disorders include Glanzmanns thrombasthenia and Bernard-Soulier syndrome, both of which

are rare autosomal recessive disorders. Acquired

platelet disorders can result from uremia and certain

drugs (eg, aspirin, NSAIDs). Uremia causes abnormal

platelet function by unknown mechanisms.

Platelet Disorders Associated with Easy Bruising

Platelet disorders can be divided into quantitative

and qualitative abnormalities.4,5 Quantitative disorders

are characterized by thrombocytopenia resulting from

sequestration, peripheral destruction, or decreased

production of platelets (Table 2).4,5 Bone marrow disorders causing thrombocytopenia include aplastic anemia, myelodysplasia, and hematologic malignancies.

Chronic alcoholism can also cause marrow suppression. Nonmarrow disorders causing thrombocytopenia

include disseminated intravascular coagulation, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, hemolytic uremic

syndrome, liver failure, hypersplenisms, and autoim-

Illustrative Case

Case presentation. A 50-year-old woman presents

with a 3-week history of easy bruising and fatigue.

Physical examination is significant for an obese woman

with scattered areas of ecchymosis predominantly on

the lower extremities (Figure 1). Laboratory examination reveals a leukocyte count of 200 103/mm3 (normal, 4.810.8 103/mm3), hemoglobin concentration

of 9 g/dL (normal, 12.015.5 g/dL), and a platelet

count of 20 10 3 /mm 3 (normal, 150 450

103/mm3). A differential cell count shows 83% blasts.

Results of coagulation studies, including PT and activated PTT (aPTT), are normal.

36 Hospital Physician January 2005

www.turner-white.com

Karnath : Easy Bruising and Bleeding : pp. 35 39

Table 2. Causes of Thrombocytopenia

Decreased platelet production

Leukemia

Lymphoma

Aplastic anemia

Myelodysplasia

Chronic alcoholism

Vitamin B12 deficiency

Folic acid deficiency

Splenic sequestration

Cirrhosis with congestive splenomegaly

Myelofibrosis with splenomegaly

Figure 1. Area of ecchymosis (a large bruise).

Nonmarrow disorders

Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura

HIV infection

Drugs (heparin, quinidine, quinine, sulfa-containing)

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (cancer, sepsis)

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura

Hemolytic-uremic syndrome

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria

Discussion. In this case, a middle-aged woman presents with nonspecific complaints of easy bruising and

fatigue. She reports that the largest bruise, which is on

her left thigh, is the result of insignificant contact with

a waste can. The resulting bruise is out of proportion

to the force of contact. Although the patient has severe

thrombocytopenia, petechiae are not present. Results

of coagulation studies are normal, but the complete

blood count reveals a markedly elevated leukocyte

count, anemia, and severe thrombocytopenia. The

peripheral smear shows a predominance of blasts.

Acute leukemia, specifically acute myelogenous leukemia, was subsequently diagnosed.

Acute myelogenous leukemia accounts for 80% of

acute leukemias in adults and acute lymphocytic

leukemia accounts for the remaining 20%.6 Acute lymphocytic leukemia is primarily a childhood leukemia.

The median age of patients with acute myelogenous

leukemia is about 50 years.6 Approximately one third

of patients present with easy bruising or easy bleeding.

The leukocyte count is elevated and blasts are seen on

the peripheral blood smear. Moderate anemia is present

and the platelet count is often less than 20 103/mm3.

APPROACH TO THE PATIENT WITH EASY BLEEDING

A bleeding disorder should be considered in a

patient with easy bleeding, recurrent epistaxis, menorrhagia, hemarthrosis, prolonged bleeding during oper-

www.turner-white.com

ations and tooth extractions, hematuria, or rectal

bleeding. Although any of these conditions can occur

alone, spontaneous bleeding from multiple sites (eg,

epistaxis, hematuria, rectal bleeding) further raises the

suspicion of a bleeding disorder. A bleeding disorder

should be especially considered in a patient with any of

the aforementioned conditions together with a family

history of a bleeding disorder. In general, easy bleeding is associated with coagulation disorders, although

coexistence with platelet disorders can occur. Qualitative platelet disorders are more likely to cause easy

bleeding than quantitative disorders unless severe.

The history should focus on the onset of easy bleeding as well as a family history of hematologic disorders.

A long history of easy bleeding is an indication of an

inherited disorder, whereas acute onset of easy bleeding is indicative of an acquired disorder. A detailed history of medication use is essential. Anticoagulants such

as warfarin and heparin can prolong the PT and PTT.

Aspirin and NSAIDs can prolong the bleeding time by

inhibiting platelet aggregation. Take note of the sites

of bleeding. Spontaneous bleeding from multiple sites

is a red flag for underlying coagulopathy.

The physical examination is useful in finding clues

to an underlying cause. Lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly are signs of possible hematologic malignancy.

Chronic liver disease can lead to easy bleeding due to

depletion of vitamin Kdependent clotting factors.

Signs of chronic liver disease include scleral icterus,

spider angiomata, gynecomastia, palmar erythema,

and digital clubbing. Laboratory investigation of patients with easy bleeding should include a complete

blood count, platelet count, PT, aPTT, bleeding time,

and liver function tests.

Coagulation Disorders Associated with Easy Bleeding

Coagulation disorders can be either inherited or

Hospital Physician January 2005

37

Karnath : Easy Bruising and Bleeding : pp. 35 39

Table 3. Causes of Coagulation Disorders

Intrinsic pathway

Prekallikrein

Extrinsic pathway

High-molecular-weight

(Tissue factor pathway)

kininogen (HMWK)

Factor XII

Tissue factor (factor III)

Factor XI

Factor VII

Factor IX

Factor VIII

Common pathway

Factor X

Factor V

Factor II (prothrombin)

Fibrinogen

Factor XIII

Causes of prolonged prothrombin time

Liver disease

Vitamin K deficiency

Warfarin

Factor VII deficiency

Causes of prolonged partial thromboplastin time

Factor deficiencies:

Factor XII

Factor XI

Factor VIII (hemophilia A)

Factor IX (hemophilia B)

Figure 2. A simplified version of the coagulation pathway

showing the involved clotting factors.

von Willebrands disease

Heparin administration

Lupus anticoagulant

Acquired factor inhibitors

acquired. Inherited disorders are likely to manifest in

childhood whereas acquired disorders present later. In

evaluating a patient for coagulation disorders, a careful

history should include inquiries about excessive bleeding during previous procedures such as tooth extractions. Hereditary disorders of coagulation can be elicited through a detailed family history.

Laboratory evaluation of the coagulation pathways

incorporates 4 tests: PT, aPTT, thrombin time, and fibrinogen assays. The aPTT and PT are the most commonly performed tests of hemostasis. An understanding of the coagulation cascade is important (Figure 2).

The extrinsic, or tissue factor, pathway is the mechanism by which coagulation is initiated in response to

tissue trauma. In this pathway, released tissue factor

activates factor VII.5,8 The intrinsic pathway is activated

when blood comes in contact with an injured vessel

wall, activating factor XII.5,8 Both pathways proceed to

a common pathway that leads to the formation of a

clot by cross-linking of fibrin.

Causes of Prolonged PT

The PT evaluates the extrinsic pathway of coagulation (factors II, V, VII, X, and fibrinogen). Causes of

prolonged PT include liver disease, vitamin K deficiency, warfarin, and factor VII deficiency (Table 3).

The PT has a normal range of 11 to 15 seconds. The

clotting factors are synthesized in the liver; patients

with liver failure, therefore, whether acute or chronic,

are likely to develop coagulopathy evidenced by a

prolonged PT disproportionate to the aPTT. Patients

on prolonged antibiotic therapy are also prone to

developing coagulopathy secondary to deficiency of

the vitamin Kdependent factors (factors II, VII, IX,

38 Hospital Physician January 2005

and X). The PT is used to monitor patients on warfarin therapy.

Causes of Prolonged aPTT

The aPTT evaluates the intrinsic coagulation pathway. The test is most sensitive for factors VIII, IX, XI,

and XII. The most common cause of prolonged aPTT

is incorrect collection of blood through an indwelling

catheter that has been flushed with heparin. The aPTT

has a normal range of 22 to 38 seconds. The aPTT test

is preferred to the original PTT test.

Hemophilia A (factor VIII deficiency) is the most

common hereditary disorder of blood coagulation. The

next most common disorders are hemophilia B (factor

IX deficiency) and von Willebrands disease. Both

hemophilia A and hemophilia B are X-linked recessive

disorders only males are clinically affected and

females may be carriers. von Willebrands disease is an

autosomal dominant disorder. Acquired factor inhibitors (autoantibodies) can also develop.9 The most

common acquired inhibitor is that against factor VIII.

Illustrative Case

Case presentation. A 70-year-old man presents with

a 2-week history of hematuria, melena, and easy bruising and bleeding from minor trauma. His past medical

history is otherwise unremarkable. Physical examination is remarkable for a thin elderly man with scattered areas of ecchymosis. Rectal examination reveals

guaiac-positive stool. Laboratory examination reveals a

leukocyte count of 8.0 103/mm3, hemoglobin of

www.turner-white.com

Karnath : Easy Bruising and Bleeding : pp. 35 39

8 g/dL, platelet count of 170 10 3/mm 3, PT of

11 seconds (normal, 1115 seconds), and an aPTT of

84 seconds (normal, 2238 seconds). Laboratory results from 1 year ago (including coagulation studies)

are normal.

Discussion. In this case, an elderly man presents

with episodes of spontaneous bleeding and easy bruising. His laboratory results from 1 year ago are normal,

thereby providing evidence that his coagulopathy is

newly acquired. A family history for bleeding disorders

is negative. The patient has an isolated elevation of the

aPTT. An acquired inhibitor was suspected.

Spontaneous inhibitors are autoantibodies to coagulation factors.8 The most common factor involved is factor VIII. Factor VIII inhibition prolongs the aPTT but

not the PT. A simple test that checks for the presence of

an inhibitor (an inhibitor screen) can be performed by

incubating mixtures of patient plasma and normal plasma. Failure of the normal plasma to correct the prolonged aPTT indicates the presence of an inhibitor.

CONCLUSION

Although easy bruising and easy bleeding are often

normal, they can be ominous signs of a serious underlying disease process. Platelet disorders and coagulation disorders must be considered. A detailed family

history is important because many bleeding disorders

are inherited. Laboratory examination must include a

complete blood count and coagulation studies, including PT and aPTT.

HP

REFERENCES

1. Sham RL, Francis CW. Evaluation of mild bleeding disorders and easy bruising. Blood Rev 1994;8:98104.

2. Male I, Kenney I, Appleyard C, Evans N. Neoplasia masquerading as physical abuse. In: Child abuse review:

Journal of the British Association for the Study and

Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect. England: John

Wiley; 2000:1427.

3. Vora A, Makris M. Personal practice: an approach to

investigation of easy bruising. Arch Dis Child 2001;

84:48891.

4. Goebel RA. Thrombocytopenia. Emerg Med Clin North

Am 1993;11:44564.

5. Angelos MG, Hamilton GC. Coagulation studies: prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, bleeding

time. Emerg Med Clin North Am 1986;4:95113.

6. Devine SM, Larson RA. Acute leukemia in adults: recent

developments in diagnosis and treatment. CA Cancer J

Clin 1994;44:32652.

7. Triplett DA. Coagulation and bleeding disorders: review

and update. Clin Chem 2000;46(8 Pt 2):12609.

8. Dahlback B. Blood coagulation. Lancet 2000;355:

162732.

9. Green D. Spontaneous inhibitors to coagulation factors.

Clin Lab Haematol 2000;22 Suppl 1:2132.

Copyright 2005 by Turner White Communications Inc., Wayne, PA. All rights reserved.

www.turner-white.com

Hospital Physician January 2005

39

Вам также может понравиться

- ThrombocytopeniaДокумент9 страницThrombocytopenia8pvz96ktd9Оценок пока нет

- Bleeding Disorder (Paediatrics)Документ95 страницBleeding Disorder (Paediatrics)Nurul Afiqah Mohd YusoffОценок пока нет

- 5hematologic DiseaseДокумент40 страниц5hematologic DiseaseAli SherОценок пока нет

- 1 s2.0 S0899588513000701 Main PDFДокумент8 страниц1 s2.0 S0899588513000701 Main PDFRicki HanОценок пока нет

- Anasarca - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfДокумент5 страницAnasarca - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelfemail lombaОценок пока нет

- Peripheral Arterial Disease: AbnetДокумент142 страницыPeripheral Arterial Disease: AbnetAbnet WondimuОценок пока нет

- BUERGER's Inavasc IV Bandung 8 Nov 2013Документ37 страницBUERGER's Inavasc IV Bandung 8 Nov 2013Deviruchi GamingОценок пока нет

- Simple Purpura (Easy Bruising Syndrome)Документ4 страницыSimple Purpura (Easy Bruising Syndrome)Rebecca WongОценок пока нет

- Essential ThrombocytosisДокумент12 страницEssential ThrombocytosisGd Padmawijaya100% (1)

- ThrombocytopeniaДокумент4 страницыThrombocytopeniaValerrie NgenoОценок пока нет

- Anemi Aplastik Dan MielodisplasiaДокумент34 страницыAnemi Aplastik Dan MielodisplasiaRoby KieranОценок пока нет

- roDAKS Chapter 37Документ3 страницыroDAKS Chapter 37John DavidОценок пока нет

- Data Interpretation For Medical StudentДокумент18 страницData Interpretation For Medical StudentWee K WeiОценок пока нет

- What Is ThrombocytosisДокумент3 страницыWhat Is ThrombocytosisFred C. MirandaОценок пока нет

- Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding.Документ13 страницUpper Gastrointestinal Bleeding.Gieselle Scott100% (1)

- Haemolytic Anaemia and Sickle Cell DiseaseДокумент26 страницHaemolytic Anaemia and Sickle Cell DiseaseGideon HaburaОценок пока нет

- Hemorrhage Lec 1Документ30 страницHemorrhage Lec 1balachris64Оценок пока нет

- Aortoiliac Occlusive DiseaseДокумент37 страницAortoiliac Occlusive Diseasewolff_512Оценок пока нет

- Hemorrhagic Shock Clinical Presentation: HistoryДокумент12 страницHemorrhagic Shock Clinical Presentation: HistoryVictor Hugo SchneiderОценок пока нет

- Why Does My Patient Have Thrombocytopenia PDFДокумент22 страницыWhy Does My Patient Have Thrombocytopenia PDFElena Villarreal100% (1)

- HemorrhageДокумент8 страницHemorrhageammarmashalyОценок пока нет

- Blue Toe SyndromeДокумент20 страницBlue Toe SyndromeDaeng MakelloОценок пока нет

- 5.the Kidney - 5Документ19 страниц5.the Kidney - 5madhuОценок пока нет

- Arterial Stenosis or OcclusionДокумент83 страницыArterial Stenosis or OcclusionMuhammad Umer Farooq NadeemОценок пока нет

- Essential Thrombocytemia: Rahmawati Minhajat A. Fachruddin BenyaminДокумент12 страницEssential Thrombocytemia: Rahmawati Minhajat A. Fachruddin BenyaminHajrahPalembanganОценок пока нет

- Osler-Weber-Rendu Disease - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfДокумент4 страницыOsler-Weber-Rendu Disease - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfanaОценок пока нет

- Kuliah Platelets DisordersДокумент22 страницыKuliah Platelets DisordersDesi AdiyatiОценок пока нет

- 3 Renal Vascular Disease 3Документ46 страниц3 Renal Vascular Disease 3Coy NuñezОценок пока нет

- Anemia Hip Pain Sickle Cell DiseaseДокумент9 страницAnemia Hip Pain Sickle Cell DiseasePerplexed CeleryОценок пока нет

- The Spleen: Schwartz's Principles of Surgery 11th EdДокумент54 страницыThe Spleen: Schwartz's Principles of Surgery 11th EdaddelinsОценок пока нет

- Aplastic AnemiaДокумент29 страницAplastic AnemiaAshish SoniОценок пока нет

- Deep Vein ThrombosisДокумент43 страницыDeep Vein Thrombosisoctaviana_simbolonОценок пока нет

- Hematologic Disorders: JeffreyДокумент582 страницыHematologic Disorders: JeffreyPalak GuptaОценок пока нет

- The Spleen: Schwartz's Principles of Surgery 11th EdДокумент54 страницыThe Spleen: Schwartz's Principles of Surgery 11th EdMuhammad Fhandeka IsrarОценок пока нет

- Manejo Melena 2004Документ6 страницManejo Melena 2004Wilmer JimenezОценок пока нет

- Ischemic Limb Gangrene With PulsesДокумент14 страницIschemic Limb Gangrene With PulsesJustin Ryan TanОценок пока нет

- Acute Gastrointestinal Bleeding Upper GI BleedingДокумент18 страницAcute Gastrointestinal Bleeding Upper GI BleedingAldwin AyuyangОценок пока нет

- ThrombocytopeniaДокумент9 страницThrombocytopeniaamjad_muslehОценок пока нет

- Peripheral Arterial OcclusionДокумент50 страницPeripheral Arterial Occlusionshefalika mandremОценок пока нет

- Tromboembolismo FelinoДокумент18 страницTromboembolismo FelinoFelipeОценок пока нет

- Diagnostic Approach To The Patient With CirrhosisДокумент17 страницDiagnostic Approach To The Patient With CirrhosisXimenaEspinaОценок пока нет

- Hemostasis - Hematology BlockДокумент40 страницHemostasis - Hematology BlockamandaОценок пока нет

- Aplastic AnemiaДокумент9 страницAplastic AnemiaGaluh Dyah PrameswariОценок пока нет

- Jurnal: Lila Esi Mustika, Amkg NIK: PK2013050Документ11 страницJurnal: Lila Esi Mustika, Amkg NIK: PK2013050lilaОценок пока нет

- Introduction To Vascular SurgeryДокумент13 страницIntroduction To Vascular Surgeryapi-3858544100% (1)

- Disorder of PlateletsДокумент27 страницDisorder of PlateletsRoby KieranОценок пока нет

- ENDOCRINE HYPERTENSION. A Number of Hormonal Secretions May Produce Secondary HyДокумент5 страницENDOCRINE HYPERTENSION. A Number of Hormonal Secretions May Produce Secondary HyIsak ShatikaОценок пока нет

- Massive Bleeding/Major Hemorrhage: DefinitionДокумент6 страницMassive Bleeding/Major Hemorrhage: DefinitionGerome Isaiah RabangОценок пока нет

- Arterial InsufficiencyДокумент48 страницArterial InsufficiencySyAmil MeNzaОценок пока нет

- Aplastic Anemia - An Overview: DR Aniruddh Shrivastava Guided By: DR S.H. Talib SIRДокумент42 страницыAplastic Anemia - An Overview: DR Aniruddh Shrivastava Guided By: DR S.H. Talib SIRdoctoranswerit_84161Оценок пока нет

- PVDДокумент7 страницPVDmiss RNОценок пока нет

- Venous Thromboembolic DiseaseДокумент27 страницVenous Thromboembolic DiseaseAndra BauerОценок пока нет

- Lo Minggu 2Документ16 страницLo Minggu 2inaseptОценок пока нет

- 10.21.09 Jenkins TTPДокумент16 страниц10.21.09 Jenkins TTPOdiliaDeaNovenaОценок пока нет

- Chapter 146excessive Bleeding and BruisingДокумент7 страницChapter 146excessive Bleeding and BruisinghgpОценок пока нет

- Penatalaksanaan CAPДокумент31 страницаPenatalaksanaan CAPridhoОценок пока нет

- Asepsis and Infection ControlДокумент24 страницыAsepsis and Infection Controlabdisalaan hassanОценок пока нет

- Insuficienta Renala Acuta, Leziunea Acuta RenalaДокумент40 страницInsuficienta Renala Acuta, Leziunea Acuta RenalaLeoveanu MirelОценок пока нет

- Makalah Leigh Disease by Boys KДокумент6 страницMakalah Leigh Disease by Boys KAzizul HakimОценок пока нет

- 1-29-20 Diabetes Protocol Draft With Pandya and Alvarez EditsДокумент12 страниц1-29-20 Diabetes Protocol Draft With Pandya and Alvarez Editsapi-552486649Оценок пока нет

- ShouldiceДокумент16 страницShouldiceAbdullah AhmedОценок пока нет

- Homeopathic ImmunizationДокумент53 страницыHomeopathic Immunizationalex100% (2)

- Case Study UrtiДокумент9 страницCase Study UrtiRonica GonzagaОценок пока нет

- Karya - KTI - Poltekkes Kemenkes SurakartaДокумент11 страницKarya - KTI - Poltekkes Kemenkes Surakartasheenazz •Оценок пока нет

- Review Material Exam TypeДокумент9 страницReview Material Exam TypeFelimon BugtongОценок пока нет

- Congenital Anomalies and Variations of The Bile and Pancreatic Ducts - Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography Findings, Epidemiology and Clinical SignificanceДокумент19 страницCongenital Anomalies and Variations of The Bile and Pancreatic Ducts - Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography Findings, Epidemiology and Clinical SignificanceRoberto HernandezОценок пока нет

- D Dimer Test in VTEДокумент35 страницD Dimer Test in VTEscribmedОценок пока нет

- Letting Go by Atul GawandeДокумент18 страницLetting Go by Atul Gawandetakoyakilovers100% (2)

- Renal NursinglДокумент36 страницRenal NursinglgireeshsachinОценок пока нет

- Microbiology: Pathogenic Gram-Positive Cocci (Streptococcus)Документ26 страницMicrobiology: Pathogenic Gram-Positive Cocci (Streptococcus)Shuler0071Оценок пока нет

- Perineal Techniques During The Second Stage of Labour For Reducing Perineal Trauma (Review)Документ118 страницPerineal Techniques During The Second Stage of Labour For Reducing Perineal Trauma (Review)Ppds ObgynОценок пока нет

- Thrombocytopenia: Decreased Production Increased Destruction Sequestration PseudothrombocytopeniaДокумент43 страницыThrombocytopenia: Decreased Production Increased Destruction Sequestration PseudothrombocytopeniaDea Tasha MeicitaОценок пока нет

- Temporal Bone Radiology ReadyДокумент136 страницTemporal Bone Radiology Readyadel madanyОценок пока нет

- What Is-Thrombocythemia and ThrombocytosisДокумент4 страницыWhat Is-Thrombocythemia and ThrombocytosisFred C. MirandaОценок пока нет

- Difference Between Serum and PlasmaДокумент2 страницыDifference Between Serum and PlasmaCynthia Adeline SОценок пока нет

- Spiggle & Theis BrochureДокумент8 страницSpiggle & Theis BrochureHaag-Streit UK (HS-UK)Оценок пока нет

- ANC ModuleДокумент103 страницыANC ModulePreeti ChouhanОценок пока нет

- Hematology Unit: Complete Blood Count (CBC)Документ2 страницыHematology Unit: Complete Blood Count (CBC)Rasha ElbannaОценок пока нет

- MCQs in para (With Answers)Документ20 страницMCQs in para (With Answers)janiceli020785% (26)

- BreechДокумент2 страницыBreechBrel KirbyОценок пока нет

- NCP Ko BabyДокумент3 страницыNCP Ko BabyDaniel ApostolОценок пока нет

- Intramedullary Spinal Cord Tumors: Part II - Management Options and OutcomesДокумент10 страницIntramedullary Spinal Cord Tumors: Part II - Management Options and OutcomeszixzaxoffОценок пока нет

- Groove Pancreatitis - Cause of Recurrent PancreatitisДокумент7 страницGroove Pancreatitis - Cause of Recurrent PancreatitisroxxanaОценок пока нет

- Preterm Neonate VS AssessmentДокумент10 страницPreterm Neonate VS AssessmentggggangОценок пока нет

- Blocked Goat Urolithiasis HandoutДокумент22 страницыBlocked Goat Urolithiasis Handoutapi-262327869100% (1)