Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Introduction To ACT

Загружено:

Ran AlmogОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Introduction To ACT

Загружено:

Ran AlmogАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

CBPRA-00427; No of Pages 9: 4C

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

Cognitive and Behavioral Practice xx (2012) xxx-xxx

www.elsevier.com/locate/cabp

SPECIAL SERIES

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

Series Editor: Michael P. Twohig

Introduction: The Basics of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

Michael P. Twohig, Utah State University

This is the introductory article to a special series in Cognitive and Behavioral Practice on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

(ACT). Instead of each article herein reviewing the basics of ACT, this article contains that review. This article provides a description of

where ACT fits within the larger category of cognitive behavior therapy (CBT): CBT is an overarching term for a whole cluster of

therapies, and ACT is one of many forms of CBT. Functional contextualism and how it informs ACT is briefly reviewed. The behavior

analytic account of cognition that informs ACT, relational frame theory (RFT), and rule-governed behavior are covered. Psychological

flexibility and the 6 resulting psychological processes of change (acceptance, defusion, being present, self as context, values, and

committed action) are described. The empirical support for ACT and its related model are presented. Finally, characteristics of the ACT

model, including its therapeutic approach, desired outcomes, and processes of change, are reviewed.

special series on Acceptance and Commitment

Therapy (ACT) contains eight empirical papers on

the efficacy of ACT, its target processes, or how to administer it. Rather than having each author review the basic

concepts and terms used in ACT, this article will serve that

purpose. This article describes where ACT fits in the

larger field of CBT; the philosophical model on which

ACT is based, functional contextualism; the behavior

analytic account of cognition that informs ACT, relational

frame theory (RFT) and rule-governed behavior; the psychological construct that this model addresses, psychological flexibility; the empirical support for ACT and its

related model; and characteristics of the ACT model,

including its therapeutic approach, desired outcomes,

and processes of change.

HIS

ACT as a Type of CBT

There are many types of CBT, including traditional

cognitive therapy presented by Dr. Aaron Beck, exposure

with response prevention, dialectical behavior therapy,

schema therapy, and motivational interviewingto name

only a few. Because a large enough group of cognitive

Keywords: ACT; mindfulness; treatment; Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

behavioral therapies existed (by the early 2000s) that focused more heavily on processes such as acceptance, mindfulness, and second-order change, Hayes (2004) suggested

that a third wave of behavior therapy might be occurring

(with the first wave being behavior therapy and the second

wave being traditional cognitive therapy). This concept was

presented as the emergence of a new set or formulation of

dominant assumptions, methods, and goals, some implicit,

that help organize research, theory, and practice (p. 640).

The third wave was said to be not a rejection of the first

and second waves of behavioral and cognitive therapy

(p. 660) but rather a healing old wounds and divisions

between behavioral and cognitive perspectives (p. 660) that

encouraged the transformation of these earlier phases into

a new, broader, more interconnected form (p. 660). The

language of waves, however, led to a concern that previous

forms of CBT were being replaced and thus led to written

and verbal debates over whether there really is a third wave

and if it is anything new (Hofmann & Asmundsun, 2008).

This phase of concern seems to have passed, and ACT and

other new methods are now well positioned within larger

CBT as forms of contextual cognitive behavior therapy.

ACT is thus a form of CBT, with CBT being an umbrella

term for the larger number of therapies that fall under the

cognitive behavioral model.

Functional Contextualism

1077-7229/12/xxx-xxx$1.00/0

2012 Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies.

Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

ACT comes from a philosophical framework called

functional contextualism (Hayes, Hayes, & Reese, 1988;

Please cite this article as: Twohig, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Cognitive and Behavioral Practice (2012), doi:10.1016/

j.cbpra.2012.04.003

Twohig

Hayes, Hayes, Reese, & Sarbin, 1993). This philosophical

approach shares many similarities with radical behaviorism, and in part for that reason ACT is considered a form

of clinical behavior analysis (Dougher & Hayes, 2000).

While philosophical assumptions are not usually at the

forefront of a therapeutic approach, in the case of ACT,

its philosophy of science guides most aspects of its research

and administration. Functional contextualism is not argued

to be chosen as ACT's philosophical stance because it is

inherently the best or right: it is simply stated, from the

beginning, as the chosen philosophic model and its

outcomes are judged against its goals. Its explication is

necessary because these assumptions emphasize the central

pragmatic concerns in developing and utilizing this

therapy.

There are many elements of functional contextualism

that are worth familiarizing oneself with if interested in

ACT, but for the sake of brevity, two main concepts will

be reviewed: the chosen unit of analysis and its truth

criterion. The whole event is studied from the functional

contextual model. Elements of the larger event are generally not studied in isolation because doing so may

disregard important contextual features to any action.

This issue is that formally similar actions may have very

different functions depending on context. Knowing the

function of an action is important to successfully intervene

on that behavior. This is similar to the way reinforcers and

punishers are definedfunctionally, not topographically.

The same thing applies to all inner experiences (thoughts,

feelings, bodily sensations): none are inherently problematic or positive; it all has to do with how they function for the

person.

The truth criterion of contextualism is effective action;

functional contextualism refines that general criterion

to a more specific goalprediction and influence with

precision, scope, and depth (Hayes et al., 1993). All truth

criterions provide a metric against which success can be

measured, and merely allows principles, theories, and

methods to be judged against predefined goals. This

applies to therapy outcomes as well as the larger scientific

endeavor. If functional contextual science does not result

in effective clinical interventions and progressive ways of

doing scientific work, then it fails. If meaningful clinical

outcomes are seen and its related science is progressing in

a useful manner, then it is succeeding. This differs from

other models, such as mechanistic or developmental

models, that might be more interested in constructing

models of the parts, relations, and forces that make up the

world, or predicting and observing the pattern of growth.

Functional contextualism also highlights the need for the

science to be progressive by demanding that the work

cohere with other scientific levels and domains (that is

what is meant by depth), while maintaining a suitable

level of precision and utility within the field of psychology.

Clinically, functional contextualism leads to certain

theoretical viewpoints that are central to ACT. First,

because of the emphasis on influence, ACT takes on a

behavioral viewpoint of inner experiences. Inner experiences are seen as responses to environmental events rather

than independent causes of action. From a behavioral

perspective, an event may evoke or elicit a particular inner

experience, and that inner experience may influence one's

actions, but the cause is back in the environment. This is

partially why inner experiences are addressed with acceptance and mindfulness strategies rather than more direct

strategies such as cognitive challenging. ACT attempts to

take the cognitions out of the way so that the individual

can better interact with the actual contingencies. Additionally, the goal of successful working is not restricted to

diagnosable disorders; this ties into the great number of

ACT studies that address issues of social importance that

are not diagnosable disordersfor example, increasing

the use of evidence-based practices (Varra, Hayes, Roget, &

Fisher, 2008), infertility stress (Peterson & Eifert, 2011),

and marital distress (Peterson, Eifert, Feingold, & Davidson,

2009), to name a few.

Behavior Analytic Account of Cognition: RFT

Consistent with the functional contextual philosophy

of science, an account of cognition that is clinically useful

is needed to guide the larger base of work that informs

ACT. Two lines of research from behavior analysis inform

ACT: RFT (Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, & Roche, 2001) and

rule-governed behavior (Hayes, 1989), both of which have

a considerable research base; therefore, only a cursory

review can occur here.

RFT

Cognitive humans do not simply respond to the formal

properties of the stimuli that we interact with like other

nonverbal animals do. A dog trained to respond to a

stimulus will respond similarly to ones that share formal

properties with it (stimulus generalization). Humans with

cognitive abilities have a way of effectively responding to

stimuli (external and internal) based on properties that

go beyond direct experience or stimulus generalization;

we can respond to stimuli based on a learned ability to

relate stimuli mutually and in combination and to alter

their functional properties on that basis (Hayes et al.,

2001). Relational framing of this kind is argued to be

learned, operant behavior, meaning we learn through

multiple exemplars and shaping when and how to

relationally respond to stimuli. There are many tested

forms of relational responding including, same, different,

better, time, and cause.

The type of relational framing that will occur is guided

by contextual cues, one set guiding relations themselves

and another guiding the functions of the stimuli that are

Please cite this article as: Twohig, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Cognitive and Behavioral Practice (2012), doi:10.1016/

j.cbpra.2012.04.003

Introduction: Basics of ACT

altered by a relational network. Laboratory research has

shown that the type of relation and the derived function

are governed by these different contextual features.

Written more colloquially, what a stimuli is and its suggested response are under the control of different features of

the environment. This has meaningful clinical implications in that therapy can either address the relational or

functional context that external stimuli or inner experiences occur in. ACT by and large focuses on the

functional context because research has shown that

once relational contexts are trained they cannot be

untrained (Wilson & Hayes, 1996), but that the functional

context under which stimuli occur can be altered while

leaving what a stimuli is in place (Hooper, Saunders, &

McHugh, 2010). Thus, if a client is having the thought, I

am a terrible person, instead of addressing the accuracy

of that thought, ACT would work with the person to

experience that thought in a way that does not negatively

affect his actions while possibly allowing the content of the

thought to stay the same.

gencies suggest is most effective. New rules will be created,

but additional methods are used so that the client stays

open to the likelihood that these contingencies too may

change. This illustrates the focus in ACT on behavior

change as well as flexibility with cognitions.

This is an overarching theme in a functional contextual account of language and cognitionour verbal and

cognitive abilities are very useful, but they can also have

a dangerous side. Thus, the corresponding therapeutic

approaches will focus on finding ways to utilize our verbal

abilities, while at the same time learning when to step

back from them and not follow them when they are not

useful. Events outside us and our thoughts, feelings, and

emotions will push us into actions that are not in our best

interest, and basic research suggests there are instances

when these events can be altered and instances when they

cannot be changed. The key is to determine this difference and make useful choices in these situations.

Rule-Governed Behavior

One of the implications of relational framing is that we

can create cognitive networks that represent the way

environmental contingencies function. Unfortunately,

these cognitively specified contingencies may not reflect

the environment contingencies actually in place and thus

can lead to dysfunctional behavior patterns. In general,

the ability to develop cognitive contingencies is useful

because it allows us to create effective behavior plans

without direct experience, but can also be at the root

of many forms of psychopathology. A simple example is

someone with obsessive-compulsive disorder developing

a rule that a ritualized shower is necessary to rid oneself

of germs and that any interruption of the ritual results

in recontamination. The core of this rule, showering is

good, is useful: but the verbally constructed rule (that

the ritual must be followed) does not accurately represent

the way the world works. The result of this verbal rule is

that the person follows it rather than following the actual

contingency that would indicate something other than

the verbal rule.

The most notable finding from rule governance

research is that cognitive rules make us less sensitive to

environmental contingencies (Hayes, 1989). Again, cognitive rules may be useful in some contexts and

problematic in others; the client needs to be aware of

learned or derived rules, and show the flexibility to follow

them in some situations and not follow them in others.

Oftentimes, it is problematic to either follow inaccurate

rules or follow useful rules too rigidly. Therefore, in ACT,

many direct and subtle steps are taken to help the client

contact actual environmental contingencies so that they

may shape behavior to what the environmental contin-

Because language is viewed as a pragmatic tool, ACT

theorists have attempted to construct a functional

contextual model of psychopathology and psychotherapy

that uses a series of psychological constructs that are more

easily disseminated and understood than the basic terms

of behavioral principles and RFT. The mid-level terms in

these clinical models are themselves analyzed using basic

terms and experimentation, thus there is a conscious effort

to keep traffic flowing on the bridge between applied and

basic sciences. Basic work in behavior analysis on learning

and on cognition, applied research on these psychological

constructs and their utility, and efficacy and effectiveness

studies on the resulting clinical intervention all work

together to inform this line of work. The treatment model

is designed to be clinically accessible, however, so that

practitioners need not understand RFT and similar

concepts to begin to use ACT.

The Resulting Clinical Model: Development of

Psychological Flexibility

Psychological Flexibility

The core functional concept from this model is psychological flexibility, which is the ability to fully contact the present

moment and the inner experiences that are occurring,

without needless defense, and, depending upon the context,

persisting or changing in the pursuit of goals or personal

values (Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda, & Lillis, 2006). It is

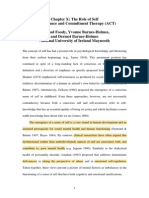

the opposite of psychological inflexibility (see Figure 1), which

is argued to be a core process in psychopathology (Hayes

et al., 2006). In order to address psychological flexibility, this

model targets six easily understood psychological processes

of change.

ACT

ACT directly aims to increase psychological flexibility,

and it does this through the following six psychological

Please cite this article as: Twohig, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Cognitive and Behavioral Practice (2012), doi:10.1016/

j.cbpra.2012.04.003

Twohig

I flexibly pay attention to

what is occurring in the

present moment

high

ATTENTION TO

PRESENT SCALE

I willingly

accept my

thoughts and

feelings even

when I dont

like them

low

high

ACCEPTANCE

SCALE

I spend

most of my time on

attentional autopilot

high

low

low

I constantly

struggle with

my thoughts

and feelings

DEFUSION

SCALE

I see each of

my thoughts

as just one of

many ways to

think about

things what

I do next is up

to me

high

low

I am clear

about what I

choose to

value in life

I dont

know what

I want

from life

My thoughts tell me

how things really

are and what I need

to do

The person I call

me is my

thoughts and

feelings about

myself

VALUES

CLARITY SCALE

I dont manage

to act on the

things I care

about

low

SELF AS

CONTEXT

SCALE

low

COMMITMENT &

TAKING ACTION

SCALE

high

I identify the

actions I need

to take to put

my values into

practice, and I

see them

through

high

The person I call me

knows what I am

thinking and feeling

but is distinct from

that process

Figure 1. Clinical descriptions of low and high presence of the six ACT processes of change. Note. Based on the ACT ADVISOR by David

Chantry and used with permission.

processes of change: acceptance, defusion, being present,

self as context, values, and behavioral commitments, all

of which have considerable support outside of larger

treatment packages (Hayes et al., 2006; Ruiz, 2010). As

can be seen in Figure 1, each of these processes of change

is at one end of a continuum and its opposite process

of change is at the other. Consistent with the functional

philosophy that ACT is based on, the more functional

end of this spectrum is context dependent. For example,

being defused from anxious thoughts can be useful

when giving an important lecture, but some fusion with

thoughts might be useful when one is about to engage in

a dangerous activity. Part of what is taught in ACT is

developing the discrimination between these ends of each

process of change and knowing how to effectively engage

each behavior.

Acceptance. Acceptance involves actively embracing

inner experiences, while they are presently occurring, as

ongoing inner experiences. This is an action; it is not an

attitude or an opinion. We can choose to behave acceptingly

or we can work to regulate our inner experiences.

Acceptance is different than tolerance because acceptance

is viewed as a choice and involves a more welcoming stance

towards the inner experience. Acceptance targets the

context that an inner experience occurs in and decreases

the effort that one exerts to control or regulate certain inner

experiences. Acceptance is applied to inner experiences

that foster experiential avoidance, which is attempting to

reduce or avoid unwanted inner experiences when doing so

results in negative effects on one's functioning (Hayes,

Wilson, Gifford, Follette, & Strosahl, 1996). An example of

experiential avoidance could be where an individual with an

Please cite this article as: Twohig, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Cognitive and Behavioral Practice (2012), doi:10.1016/

j.cbpra.2012.04.003

Introduction: Basics of ACT

anxiety disorder either avoids or escapes situations that

bring on anxiety, or while in an anxiety-producing situation

engages in inner dialogue aimed at lessening that anxiety.

Conversely, acceptance not only involves actively being in

situations that bring on anxiety, but treating one's anxiety

in a welcoming way while it is there. Thus, while doing

exposure exercises, the therapist might ask, How open are

you to your anxiety? rather than How much anxiety are

you feeling?

Cognitive defusion. Cognitive defusion involves altering the context in which inner experiences occur in an

attempt to decrease their automatic impact and importance, allowing them to be seen as an ongoing process.

Written another way, cognitive defusion can be thought of

as reducing the literal meaning of inner experiences so

that thoughts are experienced as just thoughts, feelings

are just feelings, and bodily sensations are just bodily

sensations. Cognitive defusion is the opposite of cognitive

fusion, which is where the inner experiences are taken

literally and have a large amount of power over one's

actions. Cognitive defusion and cognitive fusion are both

useful; it is just that they need to be flexibly applied to

different situations. For example, when one is doing taxes

or grocery shopping, being fused might be useful as the

work is completed with greater speed and accuracy.

Whereas, if one is having the thought, I am worthless, it

might be more useful for the person to experience that

thought as just words and sounds and choose to not let it

influence one's actions.

Being present. Being present is when we experience

our inner experiences and events in our environments as

occurring now as opposed to focusing on events in the

past or in the future. Being present is generally defined as

flexible, fluid, and voluntary attention to internal and

external events as they are occurring, without attachment

to evaluation or judgment. Being present with one's

internal and external environment helps in experiencing

the world as it really is occurring and decreases the impact

of the cognitively constructed world. Being present entails

at least three skills: the ability to regulate attention to the

now; openly and fully experiencing what is occurring; and

labeling and describing these events in a nonjudgmental

manner. The flip side of being present is being attached

to a cognitive representation of the past or the future.

Common examples of not being present occur while

ruminating or worrying. In both these situations, the

individual is not in contact with the events that are

occurring currently, but engaged with events that have

already occurred or might occur. A client with rumination

or worry might be taught to recognize when they are not

aware of the present moment, notice its occurrence, and

refocus their attention to their current inner experiences

and events in their current environment. In ACT, it is less

about being present, but being able to notice when one is

not, and flexibly shifting attention to the present if it is in

the person's best interest.

Self as context. The conceptualized self is the you that

is constructed that is based upon self-evaluations and

categorizations. It is what we believe ourselves to be. The

clinical issue is that people will attempt to protect, retain,

or shield that conceptualization of the self even when

it leads to ineffective action. For example, if a person has

labeled himself as depressed, he may very well engage in

behaviors that continue to maintain that self-description

of depressed, out of a basic belief that a self must be

protected. In ACT, we work to develop a sense of self as

context, where the self is the place of awareness or perspective taking that allows internal and external events

to be experienced from I/here/now without being

defined by those events. From this sense of self as the

context where inner experiences occur, but is not defined

by them, we can choose to follow and adhere to our senses

of who we are in some situations and not in others. Similar

to other ACT processes, flexibility in this area is desired.

Self as context is thought to be facilitated by cognitive

defusion applied to the conceptualization of self, and by

mindfulness or other awareness exercises, showing the

interplay among the six ACT processes.

Values. In ACT, values are elements of life that we

care about that motivate us to engage in certain activities.

While there are some common values that most people

share, values are individually chosen. Values are often

contrasted with goals. Goals are obtainable, such as a

marriage. Values can only be instantiated as an aspect of

ongoing action, such as being a loving and kind husband,

and thus are more like adverbs than nouns. They can

be pursued across one's life, but they cannot be possessed

like objects. They can provide guidance, meaning, and

purpose for our actions. Functionally, clarifying values

affects the reinforcing and punishing functions of events

involved in pursuing those values. Thus, helping clarify

a client's values should help make it more likely that he

will approach stimuli that originally fostered avoidance;

in addition, reinforcers that were having little effect

may become more powerful. For example, telling a client

diagnosed with an anxiety disorder that approaching an

anxiety-provoking stimuli (and allowing the anxiety to be

there without defense) brings him a step closer to being

able to attend an event at his child's school (if parenting is a

value) would increase the reinforcing value of experiencing

anxiety.

Behavioral commitments. This is the area of ACT

where traditional behavior change procedures are

Please cite this article as: Twohig, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Cognitive and Behavioral Practice (2012), doi:10.1016/

j.cbpra.2012.04.003

Twohig

incorporated into therapy. All other processes in ACT

serve to either alter the context in which inner

experiences occur, or alter the reinforcing or punishing

effects of stimuli. Committed action is more skill based

and generally involves enacting one's values while

practicing acceptance, defusion, being present, and

treating oneself as the context where inner experiences

occur. Committed action is the continuous redirection of

behavior so as to construct larger and larger patterns of

flexible and effective behavior linked to a value. It involves

defining personal goals along a path and acting on those

goals, while practicing the other ACT strategies, thus

building larger patterns of values-oriented action. Any

behavioral intervention method can be incorporated as

part of ACT as long as it is consistent with the other ACT

processes. This can include exposure exercises, fading

procedures, or skills training activities.

Basic Therapeutic Stance

Probably one of the most notable aspects of ACT is that

it is experientially oriented. At times this means it is difficult

to move from its written description to its implementation.

In describing ACT we are using language and cognition to

teach skills that are designed in part to undermine typical

language and cognitive processes. In a sense we are fighting

fire with fire. For example, we are trying to help clients take

language less literally through conversation; we are trying to

loosen the grip of rules but in the process teaching the rule

that rules cannot be trusted; and, finally, to clarify one's

values but also hold those values lightly as they are likely to

shift over time. Thus, often the least direct or rule-forming

ways of teaching ACT processes are utilized. ACT relies

heavily on metaphors or stories, exercises and role-plays

are common in session, and examples from the client's

or the therapist's lives are also used to help develop psychological flexibility. ACT is usually not implemented

didactically; rather, a therapeutic context where these processes can be taught and practiced is common. The therapist might attempt to bring up target inner experiences

during therapy and help the client to practice using the six

processes while that inner experience is present.

One final part of ACT that may be different from some

other therapies is that in ACT, the therapist deliberately

tries to model these six ACT processes within the session.

This occurs moment to moment in session in the way

that the therapist responds to his or her inner experiences

during therapy, but also the manner in which the therapist responds to the client's inner experiences. For

example, when a client shows emotion, the therapist

would not attempt to save the client from that emotion,

but rather, show acceptance of that emotion by openly

talking about it and showing openness to its emotional

impact on the therapist. By showing acceptance of the

client's emotions and modeling the six ACT processes with

regard to the emotions that the therapist is feeling, ACT

processes are being facilitated without formal exercises.

One useful way to think about ACT is that it seeks to

establish a new context in which inner experiences are not

causal and one's behavior is guided by what he or she

chooses to hold as important in life. For example, the

feeling of depression, when viewed from an accepting and

defused standpoint, may have little influence on one's

actions; instead, client actions can be influenced by

personal values. As this context becomes powerful enough

that it is carried outside of session, it is hoped that the client

then contacts actual contingencies in the world and learns

how to function better within them.

Empirical Support for ACT

There is growing support for ACT across a broad group

of social concerns, but before these outcomes are reviewed,

the manner in which this approach and model are evaluated should be addressed. Based on the functional model

from which ACT was developed, there are no inherently

problematic behaviors. Some types of behaviors are very

likely to be problematic, but a functional assessment should

occur before that is determined. Thus, there is no

particular thought or style of thinking that is problematic

from this model; the issue is really what response the

thought leads to. Again, using OCD as an example,

obsessive thoughts are only problematic when they are

taken literally and lead to behaviors that get in the way

of the person's functioning. If someone can learn to

just notice the obsession and continue in a meaningful

direction in life, the form or frequency of that thought

would have a small impact on behavior and not need to

be addressed clinically. This highlights ACT's greater focus

on functioning rather than symptom reduction per se. This

can be contrary to how change is defined for some disorders. This issue was highlighted in a recent metaanalysis

of ACT conducted by Powers, Zum Vrde Sive Vrding,

and Emmelkamp (2009) that showed that ACT for chronic

pain had near zero effect sizes for pain intensity, but those

same effect sizes were large if using behavioral functioning

as the dependent variable (Levin & Hayes, 2009).

ACT has been tested for a surprisingly large set of

social issues, many of which are not diagnosable, although

many are (Hayes et al., 2006; Ruiz, 2010). Specifically,

ACT has been shown to be effective for a variety of anxiety

disorders (e.g., Codd, Twohig, Crosby & Enno, 2011),

mood disorders (e.g., Zettle & Rains, 1989), substance

use disorders (e.g., Hayes et al., 2004), psychotic disorders

(e.g., Gaudiano & Herbert, 2006), eating disorders and

weight issues (e.g., Juarascio, Forman, & Herbert, 2010),

impulse control disorders (e.g., Woods, Wetterneck, &

Flessner, 2006), personality disorders (Gratz & Gunderson,

Please cite this article as: Twohig, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Cognitive and Behavioral Practice (2012), doi:10.1016/

j.cbpra.2012.04.003

Introduction: Basics of ACT

2006), as well as issues confronted in behavioral medicine

(Gundy, Woidneck, Pratt, Christian, & Twohig, 2011).

ACT has also been successfully used with children (Coyne,

McHugh & Martinez, 2012) and is being applied to

individuals with developmental disabilities or brain injury

(e.g., Soo, Tate, & Lane-Brown, 2011), although in the

latter case data are not out yet. In addition, ACT has been

shown to be useful with a variety of issues that are not

diagnosable, such as parental distress associated with

raising children with developmental disorders (Blackledge

& Hayes, 2006), stigma issues (Masuda et al., 2007), helping

professionals adopt empirically supported interventions

(Varra, Hayes, Roget, & Fisher, 2008), infertility stress

(Peterson & Eifert, 2011), and marital distress (Peterson

et al., 2009), to name a few. Recent reviews and metaanalyses have suggested that ACT is more effective than

control conditions but has not been shown to be more

effective than other empirically established psychosocial

treatments such as more traditional CBT packages (st,

2008; Powers et al., 2009), although the empirical arguments are complex and in flux (e.g., Gaudiano, 2009; Levin

& Hayes, 2009; Powers & Emmelkamp, 2009).

Support for the Model

As hopefully is evident from the overarching strategy

presented here, outcomes and comparisons between

treatments is only a part of this research agenda (Hayes,

Villatte, Levin, & Hildebrandt, 2011). The issue is really in

the effectiveness of this larger line of research. If this

agenda helps to move the field forward in a meaningful

way, then it succeeded; if it does not help science progress

and help more people who are suffering, then it failed.

There appears to be evidence that this is a successful line

of research and the original goals of prediction and influence

with precision, scope, and depth seem to be supported. Prediction exists in that those with greater levels of psychological inflexibility in general suffer more and have

greater pathology (Hayes et al., 2006). Influence appears

to be supported based on the evidence that this work

is helpful clinically (Powers et al., 2009). The precision

of the model is supported in that the applied model is

supported by the basic research on language and cognition. Additionally, precision exists in that, thus far, the

evidence has generally supported psychological flexibility

as the process of change in ACT versus alternative models

such as how often or what types of thoughts occur (e.g.,

Bach & Hayes, 2002; see review by Hayes et al., 2006).

Finally, scope exists in that research within ACT seems

consistent with other lines of research both within RFT

(e.g., McHugh & Stewart, 2012) and within lines of

research that are not part of this general research program. For example, the work on thought suppression is

consistent with an ACT model of dealing with problematic

cognitions (Wenzlaff & Wegner, 2000). The way inner

experiences are addressed in ACT is also consistent with

modern accounts of behavioral processes like extinction,

which no longer suggest that behaviors are unlearned but

rather become contextually controlled (Bouton, 2000).

Contents of Special Series on ACT and Summary

of Introduction

This special series contains eight empirical papers

that are consistent with the ACT model. There are three

randomized controlled trials of ACT versus treatment as

usual: psychosocial coping with late-stage ovarian cancer

(Rost, Wilson, Buchanan, Hildebrandt, & Mutch, this

issue), borderline personality disorder (Morton, Snowdon,

Gopold, & Guymer, this issue), and depression (Folke,

Parling, & Melin, this issue). Clarke and colleagues (Clarke,

Kingston, Wilson, Bolderston, & Remington, this issue) also

provide data on ACT for treatment-resistant clients but

do so within an open trial. The multiple baseline across

participants design was used to test the effects of ACT for

self-stigma around sexual orientation (Yadavaia & Hayes,

this issue) or ACT plus behavior therapy for trichotillomania (Crosby, Dehlin, Mitchell, & Twohig, this issue).

Psychometric data on a new assessment device for values

that has both research and clinical utility is presented

(Lundgren, Luoma, Dahl, Strosahl, & Melin, this issue). In

a more basic experiment, Hussey and Barnes-Holmes (this

issue) use RFT to guide an experiment on implicit attitudes

and levels of depression and psychological flexibility.

Clearly there is a lot more work to do, but based on the

new data that are presented in this special series and the

evidence reviewed herein, this appears to be a line of work

that is worth continuing. Hopefully, it is clear that this

line of research is much more than just does ACT work for

this or that, but that the work includes theoretical and

philosophical writings; laboratory work on language and

cognition and other behavioral principles that are applied

to humans; development and refinement of the psychological constructs addressed in ACT; measure development; clinical technique development; intervention testing;

and the testing of the purported processes of change in the

treatment once it is delivered. Some of this work occurs in

basic laboratories and other work occurs in more applied

contexts; regardless, a focus on linking and translating this

work across levels of analysis is needed. Basic and applied

researchers need to continue to communicate and ask for

answers from each other. This approach appears to be an

endeavor that many of us who fall under the CBT label are

interested in and goes well beyond the brand ACT, and is

really about helping those who need it.

References

Bach, P., & Hayes, S. C. (2002). The use of acceptance and commitment

therapy to prevent the rehospitalization of psychotic patients: A

randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology,

70, 11291139. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.70.5.1129

Please cite this article as: Twohig, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Cognitive and Behavioral Practice (2012), doi:10.1016/

j.cbpra.2012.04.003

Twohig

Blackledge, J. T., & Hayes, S. C. (2006). Using acceptance and

commitment training in the support of parents of children

diagnosed with autism. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 28, 118.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J019v28n01_01.

Bouton, M. E. (2000). A learning theory perspective on lapse, relapse,

and the maintenance of behavior change. Health Psychology, 19,

5763. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.19.Supp l1.57.

Clarke, S., Kingston, J., Wilson, K. G., Bolderston, H., & Remington, B.

(this issue). Acceptance and commitment therapy for a heterogeneous group of treatment resistant clients: A treatment

development study. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice.

Codd, R. T., III, Twohig, M. P., Crosby, J. M., & Enno, A. (2011). Treatment

of three anxiety disorder cases with acceptance and commitment

therapy in a private practice. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 25,

203217. http://dx.doi.org/10.1891/0889-8391.25.3.203.

Coyne, L. W., McHugh, L., & Martinez, E. R. (2012). Acceptance and

commitment therapy (ACT): Advances and applications with

children, adolescents, and families. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric

Clinics of North America, 20, 379399. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

j.chc.2011.01.010.

Crosby, J. M., Dehlin, J. P., Mitchell, P. R., & Twohig, M. P. (this issue).

Acceptance and commitment therapy and habit reversal training for

the treatment of trichotillomania. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice.

Dougher, M. J., & Hayes, S. C. (2000). Clinical behavior analysis. In M. J.

Dougher (Ed.), Clinical behavior analysis (pp. 1125). Reno, NV:

Context Press.

Folke, F., Parling, T., & Melin, L. (this issue). Acceptance and commitment

therapy for depression: A preliminary randomized clinical trial for

unemployed on long-term sick leave. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice.

Gaudiano, B. A. (2009). st's (2008) methodological comparison of

clinical trials of acceptance and commitment therapy versus

cognitive behavior therapy: Matching apples with oranges? Behaviour

Research and Therapy, 47, 10661070. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

j.brat. 2009.07.020.

Gaudiano, B. A., & Herbert, J. D. (2006). Acute treatment of inpatients

with psychotic symptoms using Acceptance and Commitment

Therapy: Pilot results. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 415437.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.02.007.

Gratz, K. L., & Gunderson, J. G. (2006). Preliminary data on acceptancebased emotion regulation group intervention for deliberate selfharm among women with borderline personality disorder. Behavior

Therapy, 37, 2535. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2005.03.002.

Gundy, J. M., Woidneck, M. R., Pratt, K. M., Christian, A. W., & Twohig,

M. P. (2011). Acceptance and commitment therapy: The state of

the evidence in the field of health psychology. Scientific Review of

Mental Health Practice, 8, 2335.

Hayes, S. C. (1989). Rule-governed behavior: Cognition, contingencies, and

instructional control. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Hayes, S. C. (2004). Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational

frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive

therapies. Behavior Therapy, 35, 639665. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

S0005-7894(04)80013-3.

Hayes, S. C., Barnes-Holmes, D., & Roche, B. (2001). Relational frame

theory: A post-Skinnerian account of human language and cognition.

New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

Hayes, S. C., Hayes, L. J., & Reese, H. W. (1988). Finding the

philosophical core: A review of Stephen C. Popper's World

Hypotheses. Journal of Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 50, 97111.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1901/jeab.1988.50-97.

Hayes, S. C., Hayes, L. J., Reese, H. W., & Sarbin, T. R. (1993). Analytic

goals and the varieties of scientific contextualism. In S. C. Hayes,

L. J. Reese, & T. R. Sarbin (Eds.), Varieties of scientific contextualism

(pp. 1127). Reno, NV: Context Press.

Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006).

Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 125. http://dx.doi.org/

10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006.

Hayes, S. C., Wilson, K. G., Gifford, E. V., Bissett, R., Piasecki, M., Batten, S.

V., . . . Gregg, J. (2004). A preliminary trial of twelve-step facilitation

and acceptance and commitment therapy with polysubstance-abusing

methadone-maintained opiate addicts. Behavior Therapy, 35, 667688.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80014-5.

Hayes, S. C., Villatte, M., Levin, M., & Hildebrandt, M. (2011). Open,

aware, and active: Contextual approaches as an emerging trend in

the behavioral and cognitive therapies. Annual Review of Clinical

Psychology, 7, 141168. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurevclinpsy-032210-104449.

Hayes, S. C., Wilson, K. G., Gifford, E. V., Follette, V. M., &

Strosahl, K. (1996). Experiential avoidance and behavioral

disorders: A functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and

treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64, 11521168.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.64.6.1152.

Hofmann, S. G., & Asmundson, G. J. G. (2008). Acceptance and

mindfulness-based therapy: New wave or old hat? Clinical Psychology

Review, 28, 116. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr. 2007.09.003.

Hooper, N., Saunders, J., & McHugh, L. (2010). The derived

generalization of thought suppression. Learning & Behavior, 38,

160168. http://dx.doi.org/10.3758/LB.38.2.160.

Hussey I., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (this issue). The Implicit Relational

Assesssment Procedure as a measure of implicit depression and

the role of psychological inflexibility. Cognitive and Behavioral

Practice.

Juarascio, A. S., Forman, E. M., & Herbert, J. D. (2010). Acceptance

and commitment therapy versus cognitive therapy for the treatment

of comorbid eating pathology. Behavior Modification, 34, 175190.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0145445510363472.

Levin, M., & Hayes, S. C. (2009). Is Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

superior to established treatment comparisons? Psychotherapy and

Psychosomatics, 78. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000235979.

Lundgren, T., Luoma, J. B., Dahl, J., Strosahl, K., & Melin, L. (this

issue). The Bull's-Eye Values Survey: A psychometric evaluation.

Cognitive and Behavioral Practice.

Masuda, A., Hayes, S. C., Fletcher, L. B., Seignourel, P. J., Bunting, K.,

Herbst, S. A., . . . Lillis, J. (2007). Impact of acceptance and

commitment therapy versus education on stigma toward people

with psychological disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45,

27642772. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2007.05.008.

McHugh, L., & Stewart, I. (2012). The self and perspective taking: Contributions

and applications from modern behavioral science. Reno, NV: Context Press.

Morton, J., Snowdon, S., Gopold, M., & Guymer, E. (this issue).

Acceptance and commitment therapy group treatment for

symptoms of borderline personality disorder: A public sector

pilot study. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice.

st, L. G. (2008). Efficacy of the third wave of behavioral therapies: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy,

46, 296321. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2007.12.005.

Peterson, B. D., & Eifert, G. H. (2011). Using Acceptance and Commitment

Therapy to treat infertility stress. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 18,

577587. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2010.03.004.

Peterson, B. D., Eifert, G. H., Feingold, T., & Davidson, S. (2009). Using

acceptance and commitment therapy to treat distressed couples:

A case study with two couples. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 16,

430442. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2008.12.009.

Powers, M. B., & Emmelkamp, P. M. G. (2009). Response to Is

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy superior to established

treatment comparisons? Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 78,

380381. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000235979.

Powers, M. B., Zum Vrde Sive Vrding, M. B., & Emmelkamp, P. M. G.

(2009). Acceptance and commitment therapy: A meta-analytic review.

Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 78, 7380. http://dx.doi.org/

10.1159/000190790.

Rost, A. D., Wilson, K. G., Buchanan, E., Hildebrandt, M. J., & Mutch D.

(this issue). Improving psychological adjustment among late-stage

ovarian cancer patients: Examining the role of avoidance in

treatment. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice.

Ruiz, F. J. (2010). A review of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

(ACT) empirical evidence: Correlational, experimental psychopathology, component and outcome studies. International Journal of

Psychology & Psychological Therapy, 10, 125162. http://dx.doi.org/

10.1080/028457199439937.

Soo, C., Tate, R. L., & Lane-Brown, A. (2011). A systematic review of

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) for managing

anxiety: Applicability for people with acquired brain injury? Brain

Impairment, 12, 5470.

Please cite this article as: Twohig, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Cognitive and Behavioral Practice (2012), doi:10.1016/

j.cbpra.2012.04.003

Introduction: Basics of ACT

Varra, A. A., Hayes, S. C., Roget, N., & Fisher, G. (2008). A randomized

control trial examining the effect of acceptance and commitment

training on clinician willingness to use evidence-based pharmacotherapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 449458.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.76.3.449.

Wenzlaff, R. M., & Wegner, D. M. (2000). Thought suppression. Annual

Review of Psychology, 51, 5991. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/

annurev.psych.51.1.59.

Wilson, K. G., & Hayes, S. C. (1996). Resurgence of derived stimulus

relations. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 66,

267281. http://dx.doi.org/10.1901/jeab.1996.66-267.

Woods, D. W., Wetterneck, C. T., & Flessner, C. A. (2006). A controlled

evaluation of acceptance and commitment therapy plus habit

reversal for trichotillomania. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44,

639656. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.05.006.

Yadavaia, J. E., & Hayes, S. C. (this issue). Acceptance and

Commitment Therapy for self-stigma around sexual orientation:

A multiple baseline evaluation. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice.

Zettle, R. D., & Rains, J. C. (1989). Group cognitive and contextual

therapies in treatment of depression. Journal of Clinical Psychology,

45(3), 436445. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(198905)

45:3b436::AID-JCLP2270450314N3.0.CO;2-L.

I would like to thank Dr. Maureen Whittal for the opportunity to edit

this special series and her guidance through the process. I would also

like to thank Dr. Steven Hayes for his comments and edits to an earlier

version of this paper.

Address correspondence to Michael P. Twohig, Ph.D., Utah

State University, 2810 Old Main HI, Logan, UT 84322; e-mail:

michael.twohig@usu.edu.

Received: February 24 2012

Accepted: April 13 2012

Available online xxxx

Please cite this article as: Twohig, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Cognitive and Behavioral Practice (2012), doi:10.1016/

j.cbpra.2012.04.003

Вам также может понравиться

- Cognitive DefusionДокумент15 страницCognitive DefusionMR2692Оценок пока нет

- Luoma Cognitive DefusionДокумент17 страницLuoma Cognitive Defusionnelu onoОценок пока нет

- Cognitive Behavioral Group Therapy: Challenges and OpportunitiesОт EverandCognitive Behavioral Group Therapy: Challenges and OpportunitiesОценок пока нет

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy - An OverviewДокумент28 страницAcceptance and Commitment Therapy - An OverviewDidina_Ina100% (3)

- Dialectical Behavior Therapy: A Contemporary Guide for PractitionersОт EverandDialectical Behavior Therapy: A Contemporary Guide for PractitionersОценок пока нет

- Relational Frame Theory, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, and A Functional Analytic Definition of MindfulnessДокумент22 страницыRelational Frame Theory, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, and A Functional Analytic Definition of Mindfulnessdor8661Оценок пока нет

- The Application of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy To Obsessive Compulsive DisorderДокумент11 страницThe Application of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy To Obsessive Compulsive DisorderAnonymous Ax12P2srОценок пока нет

- Psychological Flexibility As A Mechanism PDFДокумент28 страницPsychological Flexibility As A Mechanism PDFPedro GuimarãesОценок пока нет

- The Role of Self in Acceptance and Commitment TherapyДокумент25 страницThe Role of Self in Acceptance and Commitment TherapyMark KovalОценок пока нет

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) Contacts, Resources, and ReadingsДокумент30 страницAcceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) Contacts, Resources, and ReadingsAnonymous Ax12P2srОценок пока нет

- Emotion Regulation in ACT - Steven C. HayesДокумент13 страницEmotion Regulation in ACT - Steven C. HayesVartax100% (2)

- Dymond, S., Roche, B. (2013) - Advances in Relational Frame Theory PDFДокумент298 страницDymond, S., Roche, B. (2013) - Advances in Relational Frame Theory PDFVartax100% (2)

- Niklas Törneke-Learning RFT - An Introduction To Relational Frame Theory and Its Clinical Application-Context Press (2010)Документ290 страницNiklas Törneke-Learning RFT - An Introduction To Relational Frame Theory and Its Clinical Application-Context Press (2010)Anahi Pegoraro100% (11)

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) Contacts, Resources, and ReadingsДокумент30 страницAcceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) Contacts, Resources, and Readingsfriedl377203100% (1)

- Practical Guide To Acceptance and Commit Men TherapyДокумент399 страницPractical Guide To Acceptance and Commit Men TherapyAlejandro García100% (6)

- ACT Guide FinalДокумент25 страницACT Guide Finalrama krishna100% (3)

- ACCEPTANCE AND Commitment TherapyДокумент71 страницаACCEPTANCE AND Commitment TherapyPedro Guimarães100% (1)

- State of The Research & Literature Address: ACT With Children, Adolescents and ParentsДокумент13 страницState of The Research & Literature Address: ACT With Children, Adolescents and Parentslibreria14Оценок пока нет

- Acceptance & Commitment Therapy - IntroductionДокумент12 страницAcceptance & Commitment Therapy - IntroductionKaryl Christine AbogОценок пока нет

- Innovations in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Clinical Advancements and Applications in ACTДокумент368 страницInnovations in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Clinical Advancements and Applications in ACTFábio Vacaro Culau100% (3)

- FACT Kirk Strosahl Presentation PDFДокумент11 страницFACT Kirk Strosahl Presentation PDFAlexander ZelenukhinОценок пока нет

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy For Leadership and Change ManagersДокумент10 страницAcceptance and Commitment Therapy For Leadership and Change ManagersmysticblissОценок пока нет

- ACT D Therapist Manual PDFДокумент132 страницыACT D Therapist Manual PDFedw68100% (2)

- The Essential Guide To The ACT Matrix A StepbyStep Approach To Using The ACT Matrix Model in Clinical Practice NodrmДокумент365 страницThe Essential Guide To The ACT Matrix A StepbyStep Approach To Using The ACT Matrix Model in Clinical Practice NodrmRan Almog100% (21)

- Learning ACT - An Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Skills-Training Manual For Therapists (PDFDrive)Документ379 страницLearning ACT - An Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Skills-Training Manual For Therapists (PDFDrive)Wesley Ramalho100% (2)

- ACT Guide FinalДокумент24 страницыACT Guide FinalJohnОценок пока нет

- The ACT Matrix K. Polk B.Schoendorff PDFДокумент281 страницаThe ACT Matrix K. Polk B.Schoendorff PDFÁngela María Páez Buitrago100% (17)

- Strosahl ACBS ACT Brief Intervention WorkshopДокумент17 страницStrosahl ACBS ACT Brief Intervention WorkshopJay MikeОценок пока нет

- ACT & Mindfulness at Work - Steven C. Hayes, Frank W. Bond, Dermot Barnes-HolДокумент186 страницACT & Mindfulness at Work - Steven C. Hayes, Frank W. Bond, Dermot Barnes-HolDavid Espinola100% (4)

- Ellis, 2005Документ16 страницEllis, 2005Jonathon BenderОценок пока нет

- Functional Analityc PsychotherapyДокумент290 страницFunctional Analityc PsychotherapyViviana92% (13)

- Kevin L. Polk PDFДокумент281 страницаKevin L. Polk PDFLeilanneArjonesОценок пока нет

- 1 RFT LearningДокумент68 страниц1 RFT LearningJéssica Lays RibeiroОценок пока нет

- ++++polk, Shoendorff, Webster y Olaz (2016) The Essential Guide For ACT MatrixДокумент287 страниц++++polk, Shoendorff, Webster y Olaz (2016) The Essential Guide For ACT MatrixVictor Canales100% (2)

- Acceptance and Commitment Training (ACT) in The WorkplaceДокумент37 страницAcceptance and Commitment Training (ACT) in The Workplacem2r71964Оценок пока нет

- Perspective TakingДокумент274 страницыPerspective TakingCarolina Silveira100% (2)

- Actand 1 PDFДокумент298 страницActand 1 PDFRoger100% (2)

- 2014 - The Big Book of ACT Metaphors - Jill A. StoddardДокумент191 страница2014 - The Big Book of ACT Metaphors - Jill A. StoddardCAMILA MEJIA LOZANOОценок пока нет

- ACT Made Simple - The Extra Bits - by Russ Harris - Textbook Support Materials - November 2021 UpdateДокумент7 страницACT Made Simple - The Extra Bits - by Russ Harris - Textbook Support Materials - November 2021 UpdateH A100% (1)

- Howard Kirschenbaum Values Clarification in Counseling and Psychotherapy Practical Strategies For Individual and Group Settings Oxford University Press 2013Документ225 страницHoward Kirschenbaum Values Clarification in Counseling and Psychotherapy Practical Strategies For Individual and Group Settings Oxford University Press 2013Andjelija Simic100% (2)

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy For TH - Walser, Robyn (Author) PDFДокумент270 страницAcceptance and Commitment Therapy For TH - Walser, Robyn (Author) PDFMoniica Macias100% (11)

- Big Book of ACT Metaphors, The - Hayes, Steven C., Stoddard, Jill A., Afari, Niloofar PDFДокумент250 страницBig Book of ACT Metaphors, The - Hayes, Steven C., Stoddard, Jill A., Afari, Niloofar PDFÁngela María Páez Buitrago96% (47)

- ACT Training Manual For Substance Abuse CounselorsДокумент9 страницACT Training Manual For Substance Abuse CounselorsSiro Vaquero CabezaОценок пока нет

- STRESS - Craig Huffman - ACT Ultim Guide To Using ACT To Treat Stress, Includ Mindfulness ExercДокумент80 страницSTRESS - Craig Huffman - ACT Ultim Guide To Using ACT To Treat Stress, Includ Mindfulness ExercCarlos Silva100% (1)

- A Contextual Behavioral Guide To The Self (2019)Документ252 страницыA Contextual Behavioral Guide To The Self (2019)Fábio Vacaro CulauОценок пока нет

- ACT Forms Handout Andrews 2011Документ32 страницыACT Forms Handout Andrews 2011Anonymous Ax12P2sr100% (8)

- Mitment Therapy Skillstraining Manual For TherapistsДокумент322 страницыMitment Therapy Skillstraining Manual For TherapistsAlejandro Picco100% (8)

- J., Stewart, I., Martell, C., & Kaplan, J.S. (2014) - ACT and RFT in Relationships PDFДокумент298 страницJ., Stewart, I., Martell, C., & Kaplan, J.S. (2014) - ACT and RFT in Relationships PDFVartax100% (6)

- Learning Process-Based Therapy - NodrmДокумент169 страницLearning Process-Based Therapy - NodrmBrintrok100% (12)

- Mitch Fryling & Linda Hayes - Motivation in Behavior Analysis: A CritiqueДокумент9 страницMitch Fryling & Linda Hayes - Motivation in Behavior Analysis: A CritiqueIrving Pérez Méndez0% (1)

- Process Based CBT Digital ExamДокумент464 страницыProcess Based CBT Digital ExamPsico Orientador100% (6)

- Kirk D. Strosahl, Patricia J. Robinson, Thomas Gustavsson Brief Interventions For Radical Change Principles and Practice of Focused Acceptance and Commitment Therapy PDFДокумент297 страницKirk D. Strosahl, Patricia J. Robinson, Thomas Gustavsson Brief Interventions For Radical Change Principles and Practice of Focused Acceptance and Commitment Therapy PDFebiznes100% (18)

- The Big Book of ACT Metaphors-2014-1Документ250 страницThe Big Book of ACT Metaphors-2014-1cristian vargas100% (3)

- Problem Solving TherapyДокумент43 страницыProblem Solving Therapyjoseph_r9512Оценок пока нет

- Hayes. Learning ACT An Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Skills Training Manual For TherapistsДокумент466 страницHayes. Learning ACT An Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Skills Training Manual For TherapistsNuni95% (21)

- Wilson, D.S., Hayes, S.C. & Biglan, A. (2018). Evolution and contextual behavioral science an integrated framework for understanding, predicting and influencing human behavior. Oakland Context Press..pdfДокумент390 страницWilson, D.S., Hayes, S.C. & Biglan, A. (2018). Evolution and contextual behavioral science an integrated framework for understanding, predicting and influencing human behavior. Oakland Context Press..pdfjesus100% (3)

- Jason B. Luoma, Steven C. Hayes, Robyn D. Walser - Learning ACT - An Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Skills Training Manual For Therapists (2017, Context Press) PDFДокумент466 страницJason B. Luoma, Steven C. Hayes, Robyn D. Walser - Learning ACT - An Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Skills Training Manual For Therapists (2017, Context Press) PDFMurilo MartinsОценок пока нет

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy For Individuals With DisabilitiesДокумент11 страницAcceptance and Commitment Therapy For Individuals With Disabilitiesjoao1504Оценок пока нет

- Nightmare Rehearsal and Sleep Hygiene - Russ Harris - WWW - imlearningACTДокумент7 страницNightmare Rehearsal and Sleep Hygiene - Russ Harris - WWW - imlearningACTRan AlmogОценок пока нет

- The Essential Guide To The ACT Matrix A StepbyStep Approach To Using The ACT Matrix Model in Clinical Practice NodrmДокумент365 страницThe Essential Guide To The ACT Matrix A StepbyStep Approach To Using The ACT Matrix Model in Clinical Practice NodrmRan Almog100% (21)

- How Is RO-DBT Different From DBT - NewHarbingerДокумент9 страницHow Is RO-DBT Different From DBT - NewHarbingerRan Almog50% (2)

- Chronic Pain ACTДокумент8 страницChronic Pain ACTRan AlmogОценок пока нет

- Hexaflex and TriflexДокумент3 страницыHexaflex and TriflexRan AlmogОценок пока нет

- ACT With DepressionДокумент9 страницACT With DepressionRan Almog100% (1)

- Baumeister - How The Self Became A ProblemДокумент14 страницBaumeister - How The Self Became A ProblemRan AlmogОценок пока нет

- Client Centered Assessment CaseДокумент5 страницClient Centered Assessment CaseHon “Issac” KinHoОценок пока нет

- Oswald in Youth HouseДокумент3 страницыOswald in Youth HouseGreg ParkerОценок пока нет

- Blackness and Disability Edited by Christopher BellДокумент171 страницаBlackness and Disability Edited by Christopher BellXian XianОценок пока нет

- Ham D PDFДокумент2 страницыHam D PDFNeach GaoilОценок пока нет

- Therapeutic ProcessДокумент24 страницыTherapeutic ProcessJavier Tracy Anne0% (1)

- Malignant Self LoveДокумент116 страницMalignant Self LoveIon Prinos100% (4)

- Letters CompДокумент5 страницLetters CompAnscarОценок пока нет

- Paul S. Appelbaum M.DДокумент54 страницыPaul S. Appelbaum M.DMarkingsonCaseОценок пока нет

- Behaviour Research and Therapy: Alan E. KazdinДокумент12 страницBehaviour Research and Therapy: Alan E. KazdinDroguОценок пока нет

- VoyeurismДокумент10 страницVoyeurismMilton ThiraviyamОценок пока нет

- Syllabus of Nursing Officer 2023Документ5 страницSyllabus of Nursing Officer 2023raviОценок пока нет

- Dissertation Proposal TextДокумент2 страницыDissertation Proposal TextJithin ThomasОценок пока нет

- Reflection Paper On Zion CentreДокумент2 страницыReflection Paper On Zion CentreDanielle Andrea CalderonОценок пока нет

- A Brief Overview of Four Principles of Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. George P. PrigatanoДокумент2 страницыA Brief Overview of Four Principles of Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. George P. PrigatanoGuillermo AlcaláОценок пока нет

- Gender Dysphoria and Social AnxietyДокумент9 страницGender Dysphoria and Social AnxietyJellybabyОценок пока нет

- A Mental Health Chatbot For Regulating Emotions (SERMO) - Concept and Usability TestДокумент12 страницA Mental Health Chatbot For Regulating Emotions (SERMO) - Concept and Usability TestMadhanDhonianОценок пока нет

- 7 Types of ADHD PDFДокумент3 страницы7 Types of ADHD PDFAamir Malik67% (3)

- (PPT) PSYCH - M - Theories of PersonalityДокумент93 страницы(PPT) PSYCH - M - Theories of PersonalitynikkiОценок пока нет

- Abnormal PsychologyДокумент8 страницAbnormal PsychologyLouise Agravio100% (1)

- Sensory BagДокумент3 страницыSensory Bagapi-541744798Оценок пока нет

- Sakhi Concept Note - WebsiteДокумент3 страницыSakhi Concept Note - WebsiteSuryamaniОценок пока нет

- Why Am I Always Angry?: Anger and The BrainДокумент4 страницыWhy Am I Always Angry?: Anger and The BrainSasidharan Rajendran100% (1)

- Borderline Personality Disorder Diagnosis and 2017 The Journal For Nurse PRДокумент2 страницыBorderline Personality Disorder Diagnosis and 2017 The Journal For Nurse PRracm89Оценок пока нет

- A Companion To Fish's Clinical PsychopathologyДокумент77 страницA Companion To Fish's Clinical PsychopathologyRobbydjan Christopher80% (5)

- Reactive Attachment Disorder PDFДокумент28 страницReactive Attachment Disorder PDFSerdar Serdaroglu100% (1)

- Dizzines - PregledniДокумент9 страницDizzines - PregledniInes StrenjaОценок пока нет

- Summary Report On Gestalt TherapyДокумент27 страницSummary Report On Gestalt Therapyconsult monz100% (2)

- DID Screening SheetДокумент5 страницDID Screening SheetIsaac CruzОценок пока нет

- Child Impact of Traumatic Event Scale EnglishДокумент3 страницыChild Impact of Traumatic Event Scale EnglishFloОценок пока нет

- 3 5326 Characteristics Matrix - InputДокумент6 страниц3 5326 Characteristics Matrix - Inputapi-313154885Оценок пока нет

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedОт EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (81)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionОт EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (404)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityОт EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (29)

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDОт EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (2)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeОт EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeРейтинг: 2 из 5 звезд2/5 (1)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsОт EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsОценок пока нет

- Love Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)От EverandLove Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)Рейтинг: 3 из 5 звезд3/5 (1)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityОт EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5)

- Manipulation: The Ultimate Guide To Influence People with Persuasion, Mind Control and NLP With Highly Effective Manipulation TechniquesОт EverandManipulation: The Ultimate Guide To Influence People with Persuasion, Mind Control and NLP With Highly Effective Manipulation TechniquesРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (1412)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.От EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (110)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessОт EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (328)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsОт EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (170)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsОт EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (4)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsОт EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeОт EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (253)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaОт EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- When the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisОт EverandWhen the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2)

- The Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlОт EverandThe Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (59)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryОт EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisОт EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1)

- Empath: The Survival Guide For Highly Sensitive People: Protect Yourself From Narcissists & Toxic Relationships. Discover How to Stop Absorbing Other People's PainОт EverandEmpath: The Survival Guide For Highly Sensitive People: Protect Yourself From Narcissists & Toxic Relationships. Discover How to Stop Absorbing Other People's PainРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (95)

- Summary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisОт EverandSummary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (8)

- Troubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social ClassОт EverandTroubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social ClassРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (27)

- Mind in the Making: The Seven Essential Life Skills Every Child NeedsОт EverandMind in the Making: The Seven Essential Life Skills Every Child NeedsРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (35)

- Sleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningОт EverandSleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (3)

- The Secret of the Golden Flower: A Chinese Book Of LifeОт EverandThe Secret of the Golden Flower: A Chinese Book Of LifeРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (4)