Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Affirmative Culture

Загружено:

Nicole DavisАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Affirmative Culture

Загружено:

Nicole DavisАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/421150 .

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Critical

Inquiry.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 149.31.21.88 on Fri, 7 Mar 2014 07:56:06 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Critical Inquiry, Armative Culture

Lauren Berlant

Many of our essayists fix on the senses as a revitalizing domain with which

to chart theories and concepts of history, aesthetics, and experience. The

words power and ideology dont make it into these paradigms much, and

questions shaped around social inequalities are either presumed or subsumed in these phrasings. Class inequality and labor-related subjectivities,

for example, are now increasingly embedded in capitalism and globalization;

and, I think, but Im not sure, critical race, feminist, and queer studies concerns are covered, covered over, or articulated in more general conceptualizations of embodiment, a term that designates the closeness to the body

of social, experiential, and aesthetic aect. Because these sublimated categories of historical subordination were not formed as aesthetic events, and

because they trouble the distance from the body that traditionally secures

the prestige of critical thought, it is not surprising that a certain disenchantment would fall upon Critical Inquirys writers and readers, motivating returns to the elegance of a greater distance, whether couched as the new

aestheticism, a better empiricism, or rigorous theory.

Were it not for Mary Pooveys and Teresa de Lauretiss finely tuned statements, this shift would seem (among our essayists, anyway) to have happened without comment. De Lauretis argues that the ambitions of the new

social movements were sustained by a hope that today appears enmeshed

in neoliberalism (p. 366). Surely the uneven global history of liberalisms

incommensurateness with itself in theory and in practice requires a more

dynamic perspective. I take that to be the promise of de Lauretiss great

phrase the time for theory is always now (p. 365). Now, though, is not

merely the definitional province of the World Bank, the IMF, nor, really, the

U.S. capitalist/Christian state and all its others. Critics and pundits alike

Critical Inquiry 30 (Winter 2004)

! 2004 by The University of Chicago. 00931896/04/30020003$10.00. All rights reserved.

445

This content downloaded from 149.31.21.88 on Fri, 7 Mar 2014 07:56:06 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

446

Lauren Berlant / Armative Culture

generate apprehensions of the present discursively. The present is something given back to us by those who reflect on it; not available to experience

as such, the sense and the sense experience of the present are eects of critical practice.

De Lauretis herself accurately notes, thinking . . . originates in an embodied subjectivity, at once overdetermined and permeable to contingent

events (p. 365). So, if one does ride the wave that turns political fatigue to

conceptual aversion, isnt that shift, along with the widespread backlash

against theory, also enmeshed in neoliberalism? Perhaps conceptual fatigue is inevitableon the model of metal fatigue, which denotes the exhaustion metal experiences on having to bear the burden of too much

weight. But I am also reminded of David Wellberys observation that theoretical projects (hes referring to poststructuralism) tend to be deemed exhausted precisely when theyre poised to do their perhaps now unglamorous

work.1

There is much more to be said on this topic, of theory and embodied

histories of the present. Who is embodied, and how, and what is served by

the sensual turn? Can we think about the relation of critical optimism to

our vertiginous awareness of escalating violence in ways that continue to

challenge our professional contexts? Or is it the case, as the New York Times

opined recently, that this is a time of resistance without a critical social

counterimaginary?2 One could dilate infinitely on these questions. My presumption throughout will be that the critical realm of the senses encompasses what the senses do empirically; what feelings are made out to mean;

and which forces, meanings, and practices are magnetized by concepts of

aect and emotion. As in In the Realm of the Senses itself, the construction

of new visceral practices in the context of massive social upheaval, perceived

as both violence and aesthetic pleasure, is the scene from which I write.

I propose for further discussion a few other approaches to these questions, noting at the outset that the matter of professional critical theorists

proper objects, projects, and attitudesmost deftly expressed in the pieces

by Robert von Hallberg and Harry Harootunianforegrounds a crucial

1. See David E. Wellbery, foreword to Friedrich A. Kittler, Discourse Networks 1800/1900, trans.

Michael Metteer and Chris Cullens (Stanford, Calif., 1990), pp. viixxxiii.

2. See John Leland, A Movement, Yes, but No Counterculture, New York Times, 23 Mar. 2003,

sect. 9, p. 1.

L a u re n B e r l a n t teaches English at the University of Chicago. She is the

author of The Anatomy of National Fantasy: Hawthorne, Utopia, and Everyday Life

(1991) and The Queen of America Goes to Washington City: Essays on Sex and

Citizenship (1997), the editor of Intimacy (2000), and a coeditor of Critical Inquiry.

This content downloaded from 149.31.21.88 on Fri, 7 Mar 2014 07:56:06 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Critical Inquiry / Winter 2004

concern. It must be the case that increasing pundit- and legislator-centered

disrespect for the humanities has had some influence on our shifting attention to objects/scenes like emotions that can be misrecognized as universals or, less grandly, as things perceivable through common sense. One

could make the same argument about the current literary critical embrace

of ethics, which, whatever else it opens up, just sounds so comforting, so

fundable, so theoretically palatable, and so politics-lite. Some of my best

friends are ethicists (well, just one), dont get me wrong; its not the field

itself that concerns me but the impulse to recement individuality-withconsciousness at the center of critical thought.

For the most part, my estimable colleagues have written armative essays about critical work and its futures. Whether or not they propose proper

objects and better horizons for critical thought, their view is that critics and

criticism will continue to sound as we currently dosmart, abstract, and

slightly overabsorbed. Only my dear departed colleague, Harootunian,

writes in a crackling tone of voice, arguing for working beyond the national,

regional, and methodological norms of disciplinary expertise, refusing the

backlash against theoretical work, and taking the risk of engaging with the

history of the present. At the same time, he pushes aside the usually cool

distance of the thinker with a series of jarring rhetorical moves, as though

the intellectual performance of composure were a threat to occupying an

analytical edge that might very well cut in any direction, back at the author

himself or at the audience of readers.3 The sharp edge of intellectual passion

opens up what you cant control; I love thought that welcomes the risk of

formlessness, the unpredictable consequences of ideas. Thats what critical

theory does when it is done well. Truisms are cut into, things come undone,

and what Gayatri Spivak calls provisional generalizations that make new

contexts for knowledge threaten the transparency of expertise along with

the phenomena under analytic scrutiny.4 Those who turn away from a scene

of thought performed in unusual modes of critical intensity, theoreticalacumen, or referential familiarity miss an opportunity for surprise learning.

On the other hand, as Harootunian argues, such resistance is well rewarded

professionally. As someone wrote in a memo once, we want to be at the

cutting edge, but not go too far.

But, not to be carried away entirely by metaprofessional polemic, I extract two issues from the pile Ive amassed that address the production of

3. See Adam Phillips, On Composure, On Kissing, Tickling, and Being Bored: Psychoanalytic

Essays on the Unexamined Life (Cambridge, Mass., 1993), pp. 4246. Phillips argues deftly that

intellectuals habits of composure are (overdetermined) modes of control.

4. See Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Subaltern Studies: Deconstructing Historiography, In

Other Worlds: Essays in Cultural Politics (New York, 1988), pp. 197221.

This content downloaded from 149.31.21.88 on Fri, 7 Mar 2014 07:56:06 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

447

448

Lauren Berlant / Armative Culture

emotion as critical inquirys object/scene. One: to talk about the senses is

to involve oneself in a discussion of the optimism of attachment, the sociability of persons across things, spaces, and practices. It represents a turn to

the human without resurrecting, necessarily, a metaphysical subject, for

sensual experience and emotions are usually thought about, these days, in

contexts of enunciation and experiencethe nation, the law, the family,

religion, mass culture, or aesthetic ambition, for example.5 Emotionology

usually intends a discussion about processes of belonging and reflexivity, of

selves oriented toward worlds that are organized by forms that provide material and subjective senses of continuity.6

Paradoxically, then, much of the best work on the senses means to deuniversalize them, rooting them somewhere in a space of time. Miriam

Hansens work in this area is exemplary.7 But what remains is the implicit

optimism of critical thought that presumes the clarity of the senses and their

phenomenological and historical place in world building. Herbert Marcuse

called this phenomenon armative culture, a phrase rarely applied to the

kind of critical work in this journals pages but nonetheless, I am arguing,

all too relevant to its practices.8

It seems hard to talk about the sociality of emotion without presuming

the clarity and coherence both of it and the world in which it is intelligible.

It is hard for thought to abandon its desire to intensify the thingness of its

thing and thus its value. After all, as Hansen argues, the training of the senses

is the bourgeois project of aesthetics, bourgeois not standing here for privileged in the bad sense but as a marker for the pleasures of capitalist modes

5. The bibliography is enormous. For recent entries see, for example, Peter Goodrich, Oedipus

Lex: Psychoanalysis, History, Law (Berkeley, 1995) and Epistolary Justice: The Love Letter as Law,

Yale Journal of Law and the Humanities 9 (Summer 1997): 24596; Julie Ellison, Catos Tears and the

Making of Anglo-American Emotion (Chicago, 1999); Representing the Passions: Histories, Bodies,

Visions, ed. Richard Meyer (Los Angeles, 2003); William M. Reddy, Emotional Liberty: Politics

and History in the Anthropology of Emotions, Cultural Anthropology 14 (May 1999): 25688 and

The Navigation of Feeling: A Framework for the History of Emotions (New York, 2001); Jacques

Rancie`re, Disagreement: Politics and Philosophy, trans. Julie Rose (Minneapolis, 1999); Brian

Massumi, Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Aect, Sensation (Durham, N.C., 2002); Michael

Warner, Publics and Counterpublics (New York, 2002); Gillian Bendelow and Simon J. Williams,

Emotions in Social Life: Critical Themes and Contemporary Issues (New York, 1998); Antonio R.

Damasio, The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness (New

York, 1999); and Avital Ronell, Stupidity (Urbana, Ill., 2002).

6. The classic work on emotionology is Peter N. and Carol Z. Stearns, Emotionology:

Clarifying the History of Emotions and Emotional Standards, American Historical Review 90

(Oct. 1985): 81336. See also, most recently, An Emotional History of the United States, ed. Peter N.

Stearns and Jan Lewis (New York, 1998).

7. See Miriam Bratu Hansen, The Mass Production of the Senses: Classical Cinema as

Vernacular Modernism, Modernism / Modernity 6 (Apr. 1999): 5977.

8. See Herbert Marcuse, The Armative Character of Culture, Negations: Essays in Critical

Theory, trans. Jeremy J. Shapiro (Boston, 1968), pp. 88133.

This content downloaded from 149.31.21.88 on Fri, 7 Mar 2014 07:56:06 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Critical Inquiry / Winter 2004

of distinction. Bourgeois suggests that the aesthetic of modernity always involves a market, even if the name of the value it gives its objects of exchange

is merit.

At the same time, aesthetic experience gifts the good life with a dierent

pacing than the working life, donating to the worker the privilege of slowness, of time to have a thought/experience whose productivity is subjective,

connecting the sensorium to something that feels noninstrumental, absorbing, and self-arming. Slowing down is a legendary tactic of antibourgeois and antinormative activity generally, but it turns out to be the

privilege of the consuming subject as well. The double person of whom

Marcuse speaks, who receives slow time as free time secured by hard work,

is not countering any norms.9 Aesthetic and critical works that seek to promote overcoming what are called the immediate gratifications of mass society are, mainly, in perfect consonance with its modes of privilege even as

they remain a marker of a dierent, or better, pace for living. Even when

the content of aesthetic experience is disturbing in a utopian, avant-garde,

or just dicult, counternormative way, one cannot say about it that its critical distance interferes with the reproduction of violence in whatever form.10

Poovey, Hansen, Frances Ferguson, and de Lauretis demonstrate this beautifully.

I propose that we turn optimism itself into a topic probably best phrased

as collective attachment. Optimism is a way of describing a certain futurism

that implies continuity with the present, but, as it does not always feel good,

attachment seems a better way to describe the pleasures of repetition without presuming their aective reverb.11 This is Marcuses point: How is it

that the bad life appears to so many as the good life yet unrealized? What

relation is there between this mode of optimistic negativity or deferral and

the pleasurable distances of aesthetic self-cultivation? At the same time that

emotions bring us toward others (even internal others, say the psychologists) in a way that merges self-continuity with the continuities of repetition

and futurity, there is a whole field of negativity that is not the opposite of

cultivated emotion. We need to give more thought to the modes of subjectivity that are disorganized, or noncoherent, or negative, or lagging in a

9. See Marcuse, Eros and Civilization: A Philosophical Inquiry into Freud (Boston, 1966),

pp. 2154.

10. I refer here to the emerging importance of the study of trauma and human rights in the

academy and of what we might call terror films in the U.S. popular public sphere, which are

remaking traditional mainstream genres from horror to melodrama. What matters, in both of

these domains, is the incomprehensibility of escalating violence everywhere. But the incitements

to paranoia and conscience do not dissolve the armative impulses of consumer survivalism.

11. For a fuller critique, situated in queer theory, of the normativity of optimism, see Lee

Edelman, No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive (forthcoming).

This content downloaded from 149.31.21.88 on Fri, 7 Mar 2014 07:56:06 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

449

450

Lauren Berlant / Armative Culture

more profound way than even Freudian Nachtraglichkeit or deferred action

would suggest.

My second point follows from the first one, then, which argues that critical theory and criticisms investment in cultivating consciousness as a good

in itself is, among other things, related to the anxieties of keeping critical

culture armative. At the same time, whether the experience of available

aesthetic phenomena provides beautiful, sublime, or palliative relief from

the business of creating value for others, along with this relief is a whole

field of negative emotion. Negative emotion is a formal category, related to

bad moods and depressions the way attachment related to optimism above.

For the last few years a project titled Feminism Unfinished has developed

a national program of local cells, dedicated to a variety of topics; one of

these is Public Feelings.12 The Chicago group calls itself a feel tank rather

than a think tank, only partly as a joke. Comprised of artists and academics,

the feel tank is organized around the thought that public spheres are aect

worlds at least as much as they are eects of rationality and rationalization.

This is a collaborative project, and collaboration is one of our topics. We

study theoretical, historical, and aesthetic materials engaged with the aects

and emotions. Right now, we are amassing for future research the negative

political emotions because most U.S. citizens and occupants have abandoned participating in the political sphere and because many who do, say,

merely vote, do it without optimism for the kind of transformative agency

that might/ought to have been a possibility. Some of these emotions: detachment, numbness, vagueness, confusion, bravado, exhaustion, apathy,

discontent, coolness, hopelessness, and ambivalence.

Our instinct is that these political emotions are often experienced as disconnection, consciousness at a distance. In the tradition of the negative dialectic, but also in other ways, what does it mean to think about the aversive

emotions of negativity as kinds of attachment? We have hosted, for example,

an International Day of the Politically Depressed. What does it mean to

think of negativity not as an eect of bad power but as a way of being critical

12. Feel Tank Chicago has a complex bureaucratic history. It is a cell in a larger system first

generated by the collaborative eort of Janet Jakobsen of the Barnard Center for Research on

Women, Elizabeth Lapovsky Kennedy of the Department of Womens Studies at the University of

Arizona, and me, when I directed the Center for Gender Studies at the University of Chicago. If

our initial impulse was to work together to honor the unfinished scholarly, aesthetic, and activist

business of the 1982 Conference on Sexuality at Barnard evidenced in the anthology Pleasure and

Danger: Exploring Female Sexuality, ed. Carol S. Vance (Boston, 1984), we moved quickly to

reimagining the form of feminist futures with feminist and queer scholars and activists from all

over, who have met collectively and in individual cells during the years since to pursue particular

interests. Transnational Feminism, Sex and Freedom, Organizing Gendered and Racialized

Communities through the Axis of Class, and Public Feelings are the most active cells.

This content downloaded from 149.31.21.88 on Fri, 7 Mar 2014 07:56:06 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Critical Inquiry / Winter 2004

without consciousness, as we currently understand its cultivated form?How

is it possible to think about cultivated subjectivity in the aesthetic sense

without implying uplift, progress, or errancy? Situated in our own contradictions, we are also restless, angry, mournful, and strangely optimistic activists of the U.S. political sphere. I close with the slogan that will be on our

first cache of T-shirts and stickers: Depressed? . . . It Might Be Political.

This content downloaded from 149.31.21.88 on Fri, 7 Mar 2014 07:56:06 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

451

Вам также может понравиться

- Berlant - Critical Inquiry, Affirmative CultureДокумент8 страницBerlant - Critical Inquiry, Affirmative CultureScent GeekОценок пока нет

- This Content Downloaded From:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff On Thu, 01 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTCДокумент30 страницThis Content Downloaded From:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff On Thu, 01 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTCIgnacio VergaraОценок пока нет

- Epistemology and The Sociology of Knowledge - The Contributions of Mannheim, Mills, and MertonДокумент31 страницаEpistemology and The Sociology of Knowledge - The Contributions of Mannheim, Mills, and Mertontarou6340Оценок пока нет

- Freedom from Reality: The Diabolical Character of Modern LibertyОт EverandFreedom from Reality: The Diabolical Character of Modern LibertyОценок пока нет

- Hartsock - Rethinking ModernismДокумент21 страницаHartsock - Rethinking ModernismНаталья ПанкинаОценок пока нет

- Steinmetz, G. (1998) - Critical Realism and Historical Sociology. A Review Article. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 40 (01), 170-186.Документ18 страницSteinmetz, G. (1998) - Critical Realism and Historical Sociology. A Review Article. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 40 (01), 170-186.lcr89Оценок пока нет

- Interpretation and Social Knowledge: On the Use of Theory in the Human SciencesОт EverandInterpretation and Social Knowledge: On the Use of Theory in the Human SciencesОценок пока нет

- This Content Downloaded From 168.176.40.143 On Mon, 07 Oct 2019 15:58:40 UTCДокумент40 страницThis Content Downloaded From 168.176.40.143 On Mon, 07 Oct 2019 15:58:40 UTCMatias IslaОценок пока нет

- The Essence of HumanismДокумент7 страницThe Essence of Humanismcliodna18Оценок пока нет

- On The Ethics and Practice of Contemporary Social Theory: From Crisis Talk To Multiattentional MethodДокумент20 страницOn The Ethics and Practice of Contemporary Social Theory: From Crisis Talk To Multiattentional MethodDaena FunahashiОценок пока нет

- Alagraa 2023 Review Essay The Underlife of The Dialectic Sylvia Wynter On Autopoeisis and Epistemic RuptureДокумент8 страницAlagraa 2023 Review Essay The Underlife of The Dialectic Sylvia Wynter On Autopoeisis and Epistemic Rupturecesar baldiОценок пока нет

- John Dunn The Identity of The History of IdeasДокумент21 страницаJohn Dunn The Identity of The History of IdeasCosmin KoszorОценок пока нет

- New Paradigm Social ScienceДокумент24 страницыNew Paradigm Social Sciencemu'minatul latifahОценок пока нет

- Gauthier Social Contract As IdeologyДокумент36 страницGauthier Social Contract As IdeologymariabarreyОценок пока нет

- Nordicom ReviewДокумент9 страницNordicom ReviewIvánJuárezОценок пока нет

- American Journal of Sociology Volume 46 Issue 3 1940 (Doi 10.2307/2769572) C. Wright Mills - Methodological Consequences of The Sociology of KnowledgeДокумент16 страницAmerican Journal of Sociology Volume 46 Issue 3 1940 (Doi 10.2307/2769572) C. Wright Mills - Methodological Consequences of The Sociology of KnowledgeBobi BadarevskiОценок пока нет

- The Assault Against Logic by Steve YatesДокумент28 страницThe Assault Against Logic by Steve YatesDeea MilanОценок пока нет

- Requiring Religion: Be What KnowsДокумент10 страницRequiring Religion: Be What KnowsS_710NОценок пока нет

- Values in Culture HerskovitsДокумент11 страницValues in Culture HerskovitsEmidioguneОценок пока нет

- Lois McNay Against Recognition 2008Документ229 страницLois McNay Against Recognition 2008cyntila100% (3)

- 41 2 pp313 321 JETSДокумент9 страниц41 2 pp313 321 JETSLazar PavlovicОценок пока нет

- Synthese Kluweracademic Publishers. Printed in The NetherlandsДокумент19 страницSynthese Kluweracademic Publishers. Printed in The NetherlandsLuiz Guilherme Araujo GomesОценок пока нет

- Catherine WilsonДокумент16 страницCatherine WilsonKyle ScottОценок пока нет

- Queer Theory XДокумент8 страницQueer Theory XHanaBezManaОценок пока нет

- Cultural Materialism1Документ34 страницыCultural Materialism1jurbina1844Оценок пока нет

- Orientalism Reconsidered Author(s) : Edward W. Said Source: Cultural Critique, Autumn, 1985, No. 1 (Autumn, 1985), Pp. 89-107 Published By: University of Minnesota PressДокумент20 страницOrientalism Reconsidered Author(s) : Edward W. Said Source: Cultural Critique, Autumn, 1985, No. 1 (Autumn, 1985), Pp. 89-107 Published By: University of Minnesota PressJoerg BlumtrittОценок пока нет

- Critical Theory 2Документ12 страницCritical Theory 2Dante EdwardsОценок пока нет

- Barnes and Bloor Relativism Rationalism and The Sociology of KnowledgeДокумент14 страницBarnes and Bloor Relativism Rationalism and The Sociology of KnowledgenicoferfioОценок пока нет

- International Phenomenological SocietyДокумент7 страницInternational Phenomenological Societyandre ferrariaОценок пока нет

- Nussbaum (2002) Humanities and Human DevelopmentДокумент12 страницNussbaum (2002) Humanities and Human DevelopmentSérgio AlcidesОценок пока нет

- Morality Essay TopicsДокумент4 страницыMorality Essay Topicsafibafftauhxeh100% (2)

- The University of Chicago PressДокумент38 страницThe University of Chicago PressstorontoОценок пока нет

- (O'Connor, Brian) Idleness A Philosophical EssДокумент105 страниц(O'Connor, Brian) Idleness A Philosophical EssKaram Abu SehlyОценок пока нет

- The MIT Press: The MIT Press Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To OctoberДокумент14 страницThe MIT Press: The MIT Press Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To OctoberLuiz PereiraОценок пока нет

- Ideological Fixation From The Stone Age To Todays Culture Wars Azar Gat Full ChapterДокумент67 страницIdeological Fixation From The Stone Age To Todays Culture Wars Azar Gat Full Chaptergail.anderson291100% (7)

- 20.2.jensen LibredeДокумент27 страниц20.2.jensen Libredef1sky4242Оценок пока нет

- 10 2307@40970650 PDFДокумент22 страницы10 2307@40970650 PDFDiogo Silva CorreaОценок пока нет

- DiCaglio - Language and The Logic of Subjectivity - Whitehead and Burke in CrisisДокумент24 страницыDiCaglio - Language and The Logic of Subjectivity - Whitehead and Burke in CrisiscowjaОценок пока нет

- Kurt Lewin Original - TraduzidoДокумент38 страницKurt Lewin Original - Traduzidomsmensonbg6161Оценок пока нет

- Latour 2004Документ25 страницLatour 2004snoveloОценок пока нет

- (Steven Lukes) Relativism Cognitive and MoralДокумент44 страницы(Steven Lukes) Relativism Cognitive and MoralJainara OliveiraОценок пока нет

- Thinking About Tradition-Religion-And Politics in Egypt TodayДокумент50 страницThinking About Tradition-Religion-And Politics in Egypt TodayROSHAR HARОценок пока нет

- 421133Документ5 страниц421133Eduardo Alejandro Gutierrez RamirezОценок пока нет

- Valor de Ser DesagradableДокумент23 страницыValor de Ser DesagradableginopieroОценок пока нет

- Crisis in Sociology: The Need For DarwinДокумент4 страницыCrisis in Sociology: The Need For DarwinDjinОценок пока нет

- 2000 On TraditionДокумент26 страниц2000 On TraditionDiegoОценок пока нет

- Capitalism and Christianity, American Style: The University of Chicago PressДокумент4 страницыCapitalism and Christianity, American Style: The University of Chicago PressJose LeonОценок пока нет

- City Research Online: City, University of London Institutional RepositoryДокумент21 страницаCity Research Online: City, University of London Institutional RepositoryRaladoОценок пока нет

- Rationality and RelativismДокумент31 страницаRationality and RelativismSamuel Andrés Arias100% (1)

- Gauthier SocialContractДокумент36 страницGauthier SocialContractMartínPerezОценок пока нет

- 2.1 Excerpts - Ericsson - Charges Against ProstitutionДокумент22 страницы2.1 Excerpts - Ericsson - Charges Against ProstitutionThanakrit LerdmatayakulОценок пока нет

- Bryce Laliberte - What Is NeoreactionДокумент51 страницаBryce Laliberte - What Is NeoreactionILoveYouButIPreferTrondheim100% (1)

- Social Theory National CultureДокумент25 страницSocial Theory National CultureHimmelfahrtОценок пока нет

- Bracher, Mark - Lacan, Discourse, and Social Change, A Psychoanalytic Cultural CriticismДокумент211 страницBracher, Mark - Lacan, Discourse, and Social Change, A Psychoanalytic Cultural Criticismgetmadnow100% (1)

- The End of TheoristsДокумент24 страницыThe End of TheoristsHarumi FuentesОценок пока нет

- A Reader's Guide To The Anthropology of Ethics and Morality - Part II - SomatosphereДокумент8 страницA Reader's Guide To The Anthropology of Ethics and Morality - Part II - SomatosphereECi b2bОценок пока нет

- Chapter 07 4th Ed Gender&AgeДокумент18 страницChapter 07 4th Ed Gender&AgeCahaya Santi SianturiОценок пока нет

- USAID Civil Society Assessment Report in BiHДокумент84 страницыUSAID Civil Society Assessment Report in BiHDejan ŠešlijaОценок пока нет

- Lesson 2 Applied EconomicsДокумент2 страницыLesson 2 Applied EconomicsMarilyn DizonОценок пока нет

- Jews N The Neo Cons-Heilbrunn & McdonaldДокумент18 страницJews N The Neo Cons-Heilbrunn & McdonaldDilip SenguptaОценок пока нет

- Company Law ProjectДокумент15 страницCompany Law ProjectParth Bhuta50% (2)

- Cultures of Anyone. Studies On CulturalДокумент309 страницCultures of Anyone. Studies On Culturalluis100% (1)

- Wahhabi' Influences, Salafi Responses: Shaikh Mahmud Shukri and The Iraqi Salafi Movement, 1745-19301Документ22 страницыWahhabi' Influences, Salafi Responses: Shaikh Mahmud Shukri and The Iraqi Salafi Movement, 1745-19301Zhang Hengchao100% (1)

- Norwegian Cultural Leadership 3Документ24 страницыNorwegian Cultural Leadership 3api-281265917Оценок пока нет

- Forced Global EugenicsДокумент37 страницForced Global EugenicsTimothy100% (3)

- Undoing Monogamy by Angela WilleyДокумент38 страницUndoing Monogamy by Angela WilleyDuke University Press100% (2)

- Approaches To The Study of Social Problems: The Person-Blame ApproachДокумент4 страницыApproaches To The Study of Social Problems: The Person-Blame ApproachsnehaoctОценок пока нет

- Hind Swaraj - LitCharts Study GuideДокумент37 страницHind Swaraj - LitCharts Study GuideJoyce AbdelmessihОценок пока нет

- Secret Wars Against Domestic Dissent. Boston, MA: South End, 1990. PrintДокумент18 страницSecret Wars Against Domestic Dissent. Boston, MA: South End, 1990. Printateam143Оценок пока нет

- Postova Banka v. Greece - AwardДокумент117 страницPostova Banka v. Greece - AwardManuel ValderramaОценок пока нет

- The Corporation in Political ScienceДокумент26 страницThe Corporation in Political ScienceJuani RománОценок пока нет

- Reso Senior CitizensДокумент2 страницыReso Senior CitizensJoan Perez100% (8)

- Malala Fahrenheit 451-2Документ6 страницMalala Fahrenheit 451-2api-285642057Оценок пока нет

- February 17Документ6 страницFebruary 17Hosef de HuntardОценок пока нет

- Gender Sensitive InstructionДокумент19 страницGender Sensitive InstructionSi LouОценок пока нет

- Maysir 1Документ19 страницMaysir 1farhan israrОценок пока нет

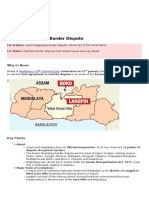

- Assam-Meghalaya Border Dispute: Why in NewsДокумент2 страницыAssam-Meghalaya Border Dispute: Why in NewsMamon DeuriОценок пока нет

- AutonomyДокумент6 страницAutonomyShekel SibalaОценок пока нет

- Transfer Certificate of Title No. T-85291Документ3 страницыTransfer Certificate of Title No. T-85291Jezel Fate RamirezОценок пока нет

- Tehran Urban & Suburban Railway (Metro) Map: TajrishДокумент1 страницаTehran Urban & Suburban Railway (Metro) Map: TajrishthrashmetalerОценок пока нет

- Reserch Rough DraftДокумент6 страницReserch Rough Draftapi-314720840Оценок пока нет

- Working Paper For The ResolutionДокумент3 страницыWorking Paper For The ResolutionAnurag SahОценок пока нет

- HR LAW List of CasesДокумент2 страницыHR LAW List of Caseslalisa lalisaОценок пока нет

- Marriage, Past and Present: A Debate Between Robert Bruffault and Bronislaw MalinowskiДокумент104 страницыMarriage, Past and Present: A Debate Between Robert Bruffault and Bronislaw Malinowskilithren100% (1)

- Domestic Violence Act Misused - Centre - The HinduДокумент8 страницDomestic Violence Act Misused - Centre - The Hinduqtronix1979Оценок пока нет

- Zombies, Malls, and The Consumerism Debate: George Romero's Dawn of The DeadДокумент17 страницZombies, Malls, and The Consumerism Debate: George Romero's Dawn of The DeadMontana RangerОценок пока нет

- The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: The Infographics EditionОт EverandThe 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: The Infographics EditionРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (2475)

- The Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismОт EverandThe Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (10)

- Summary: Atomic Habits by James Clear: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad OnesОт EverandSummary: Atomic Habits by James Clear: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad OnesРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1635)

- The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual EnlightenmentОт EverandThe Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual EnlightenmentРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (4125)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionОт EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (404)

- Summary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisОт EverandSummary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (30)

- Becoming Supernatural: How Common People Are Doing The UncommonОт EverandBecoming Supernatural: How Common People Are Doing The UncommonРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1480)

- Master Your Emotions: Develop Emotional Intelligence and Discover the Essential Rules of When and How to Control Your FeelingsОт EverandMaster Your Emotions: Develop Emotional Intelligence and Discover the Essential Rules of When and How to Control Your FeelingsРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (321)

- Indistractable: How to Control Your Attention and Choose Your LifeОт EverandIndistractable: How to Control Your Attention and Choose Your LifeРейтинг: 3 из 5 звезд3/5 (5)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeОт EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeРейтинг: 2 из 5 звезд2/5 (1)

- The 5 Second Rule: Transform your Life, Work, and Confidence with Everyday CourageОт EverandThe 5 Second Rule: Transform your Life, Work, and Confidence with Everyday CourageРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (9)

- The One Thing: The Surprisingly Simple Truth Behind Extraordinary ResultsОт EverandThe One Thing: The Surprisingly Simple Truth Behind Extraordinary ResultsРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (709)

- The Science of Self Discipline: How Daily Self-Discipline, Everyday Habits and an Optimised Belief System will Help You Beat Procrastination + Why Discipline Equals True FreedomОт EverandThe Science of Self Discipline: How Daily Self-Discipline, Everyday Habits and an Optimised Belief System will Help You Beat Procrastination + Why Discipline Equals True FreedomРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (867)

- The 16 Undeniable Laws of Communication: Apply Them and Make the Most of Your MessageОт EverandThe 16 Undeniable Laws of Communication: Apply Them and Make the Most of Your MessageРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (73)

- The Silva Mind Method: for Getting Help from the Other SideОт EverandThe Silva Mind Method: for Getting Help from the Other SideРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (51)

- The Miracle Morning by Hal Elrod: A Summary and AnalysisОт EverandThe Miracle Morning by Hal Elrod: A Summary and AnalysisРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (55)

- Summary of The Art of Seduction by Robert GreeneОт EverandSummary of The Art of Seduction by Robert GreeneРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (46)

- Own Your Past Change Your Future: A Not-So-Complicated Approach to Relationships, Mental Health & WellnessОт EverandOwn Your Past Change Your Future: A Not-So-Complicated Approach to Relationships, Mental Health & WellnessРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (85)

- Quantum Success: 7 Essential Laws for a Thriving, Joyful, and Prosperous Relationship with Work and MoneyОт EverandQuantum Success: 7 Essential Laws for a Thriving, Joyful, and Prosperous Relationship with Work and MoneyРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (38)

- Stoicism The Art of Happiness: How the Stoic Philosophy Works, Living a Good Life, Finding Calm and Managing Your Emotions in a Turbulent World. New VersionОт EverandStoicism The Art of Happiness: How the Stoic Philosophy Works, Living a Good Life, Finding Calm and Managing Your Emotions in a Turbulent World. New VersionРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (51)

- The Motive: Why So Many Leaders Abdicate Their Most Important ResponsibilitiesОт EverandThe Motive: Why So Many Leaders Abdicate Their Most Important ResponsibilitiesРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (224)

- Speaking Effective English!: Your Guide to Acquiring New Confidence In Personal and Professional CommunicationОт EverandSpeaking Effective English!: Your Guide to Acquiring New Confidence In Personal and Professional CommunicationРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (74)