Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

From Learner Corpora To Curriculum Design: An Empirical Approach To Staging The Teaching of Grammatical Concepts

Загружено:

Mary OsborneОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

From Learner Corpora To Curriculum Design: An Empirical Approach To Staging The Teaching of Grammatical Concepts

Загружено:

Mary OsborneАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Available online at www.sciencedirect.

com

ScienceDirect

Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 95 (2013) 571 580

5th International Conference on Corpus Linguistics (CILC2013)

From Learner Corpora to Curriculum Design: an Empirical

Approach to Staging the Teaching of Grammatical Concepts

*

Universidad Autnoma de Madrid, Ciudad Universitaria de Cantoblanco,28049 Madrid, Spain

Abstract

A learner corpus with texts allocated into proficiency levels is a useful resource when designing a curriculum for EFL grammar

education, as it can provide insights into which grammatical features are most critical to the learner at each stage of their

progress. However, no unproblematic methodology has arisen for using learner corpora to inform curriculum design. Some works

have compared the degree of usage of grammatical features by learners with native writers, in an attempt to identify over- and

under-use of features by the learner, and thus to take corrective measures. However, differences in usage levels between native

and learner populations does not show exactly when in a grmmar curriculum the feature should most critically be taught to

learners. Hawkins and Buttery (2010) propose using levels of usage (or negatively, levels of error) at each proficiency level to

identify to which level a feature is criterial. Where the level of usage of a feature at one level is significantly different from the

level below, it is criterial to that level. Unfortunately, for our data, many features (and error types) differ significantly on level

after level, usage at A2 differing from A1, B1 from A2, and so on. So no clear indication is available as to which level the feature

most belongs. This paper proposes an alternative approach: instead of attempting to assign features to proficiency levels, we

order the features in relation to each other. The learner corpus is used to produce an ordering of grammatical concepts in terms of

increasing difficulty for acquisition.

2013

2013The

TheAuthors.

Authors.

Published

by Elsevier

Ltd. access under CC BY-NC-ND license.

Published

by Elsevier

Ltd. Open

Selectionand

andpeer-review

peer-review

under

responsibility

of CILC2013.

Selection

under

responsibility

of CILC2013.

Keywords: learner corpora, grammar curriculum design, grammatical concepts

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +34 918-031-281.

E-mail address: Michael.odonnell@uam.es

1877-0428 2013 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. Open access under CC BY-NC-ND license.

Selection and peer-review under responsibility of CILC2013.

doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.10.684

572

Mick ODonnell / Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 95 (2013) 571 580

1. Introduction

Learner corpora have proven useful to highlight what areas of the grammar can usefully be taught to learners.

Granger (1999) for instance explores verb tense errors in high proficiency learners, and concludes that more targeted

teaching of this area can be beneficial at this proficiency level.

After answering the question of deciding what to teach, one needs to address the problem of when to teach: how

should the critical grammatical structures be packaged into a multi-semester grammar curriculum?

There has been some work in this regard. Dez Bedmar (2010), for instance, compares the use of the article

system in upper secondary and lower tertiary learners of English. More ambitious studies target a wider range of

syntactic structures at a number of distinct proficiency levels. However, most of these studies seem to get tied up on

the construction of the corpus, and never reach the point of pedagogical application. For instance, the good

intentions of Muehleisen (2006) are clear when she says:

The corpus is

develops through the course of their first few semesters. The corpus will be immediately useful for the SILS

language program developers in creating course material for the writing classes (p.119).

However, the paper makes clear that the work had not been attempted at that point. Rankin (2010) also considers

applications to the curriculum, proposing to compare the kinds of adverb errors found in student texts to those taught

in the course, with the objective of including material for common errors where they are not already covered.

results in curricul

In recent years, more attention has been turned to this issue. Of particular interest is the work of English Profile, a

el Descriptions for

English. Linked to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR), these will provide

This group, particularly in the work of Hawkins and Buttery (e.g., Hawkins and Buttery, 2009, 2010) has been

exploring the use of learner corpora to chart grammatical development with increasing proficiency, using the notion

of criterial features. They use levels of usage (or negatively, levels of error) at each proficiency level to identify to

which level a feature is criterial. Where the level of usage of a feature at one level is significantly different from the

level below, it is criterial to that level. Unfortunately, for our data, many features (and error types) differ

significantly on level after level, usage at A2 differing from A1, B1 differing from A2, etc. So no clear indication is

available as to which level the feature most belongs.

In this paper we outline an alternative approach: instead of attempting to assign features to proficiency levels, we

use the corpus to order the features in relation to each other in terms of increasing difficulty for acquisition.

Section 2 will outline the context of the current work, the research project it is part of, the corpus it makes use of,

and the annotation software we use. Section 3 explores different ways in which a learner corpus can be used to

inform grammar curriculum design, cumulating in my own proposals for difficulty-ordered tag lists. Section 4 then

offers some suggestions for applying these lists to develop a teaching curriculum, and section 5 offers some

conclusions.

2. The corpus and annotation process

The work described here took place within the TREACLE project, join work between the Universidad Autnoma

de Madrid and the Universitat Politcnica de Valencia, funded by the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovacin

(FFI2009-14436/FILO). The project is studying the linguistic production of Spanish learners of English so as to help

inform the redesign of an English grammar curriculum.

573

Mick ODonnell / Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 95 (2013) 571 580

2.1. The corpus

Two corpora were combined for the study:

The WriCLE corpus (UAM) - Written Corpus of Learner English. 521 essays of around 1000 words each,

written by Spanish learners of English at University level (about 500,000 words) (Rollinson and Mendikoetxea

2010)

The UPV Learner Corpus (UPV) containing 779 essays (150,000 words) of shorter texts by English for

Specific Purposes (ESP) students. (Andreu et al, 2010).

All essays in these corpora which were not by native Spanish speakers (of whatever variety) were eliminated, as

we are interested in the learning needs of Spanish learners of English.

2.2. Means of assessing grammatical proficiency

If one intends to use a learner corpus to help design a language curriculum, the texts in the corpus need to be

somehow related to measures of proficiency. One means of achieving this is using proficiency exams as the source

of the corpus. For instance, the English Profile group build their corpus from written answers from Cambridge

proficiency exams. Each text can thus be associated with the overall score given to the learner, be it simply passing

or failing at the level of the exam (e.g., Lower Intermediate, etc.), or an actual score. If a number of level exams are

used, the corpus can contain texts representing a progression of proficiency levels.

One problem with this approach is that exam marks represent many areas of language ability apart from

grammar, e.g., overall structure, clarity of argument, etc., and thus two exams given the same mark may in fact

represent very different kinds of proficiency, e.g., one essay with high lexico-grammatical proficiency but poor

argumentation, while another may excel in argumentation, but suffer from poor grammar. Examiners also may vary

in how they mark, some generous and others not. A third problem, if raw scores are used, is that of relating scores at

one level to those at others. What does a score of 55 in the Lower Advanced test correspond to in the next level up?

An alternative means of measuring grammatical proficiency involves the use of Placement tests. A proficiency

test has the advantage that it provides a single scale for all learners, placing beginners, intermediate and advanced

learners on one scale in relation to each other. Additionally, placement tests can target particular linguistic abilities,

for instance, the Oxford Quick Placement Test (UCLES, 2001) targets grammatical proficiency, while the full

version tests both grammatical and aural abilities.

For this work, we utilised the Oxford Quick Placement Test. This test was given to each student within a month

of writing their essay, providing a score between 0 and 60. A CEFR level can be estimated from each score, e.g., a

score between 30 and 39 relates to a CEFR level of B1.

2.3. Software

All manual and automatic annotation of the corpus was

The software runs on both Windows and MacOSX,

http://www.wagsoft.com/CorpusTool/.

and

is

available

for

free

, 2008).

from

2.4. Syntactic Annotation

UAM CorpusTool produces automatic syntactic analysis of the sentences in each text. UAM CorpusTool uses the

Stanford parser (Klein and Manning, 2003) to parse the text, and then converts this into the syntactic framework we

use for the project, something closer to a traditional analysis. Structurally, each clause is analysed in terms of

Subject, Predictor, Object, etc. and each phrase is also structured. Each unit is also assigned a set of syntactic

features representing the salient aspects we need to deal with. Features produced by the parser for each clause

include:

574

Mick ODonnell / Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 95 (2013) 571 580

TENSE: simple-present, present-perfect, present-progressive, simple-past, past-progressive, past-progressive,

simple-modal, modal-perfect, modal-progressive, etc.

FINITENESS: simple-finite, finite-with-connector, relative-clause, that-clause, wh-nominal-clause, infinitiveclause, present-participle-clause, past-participle-clause.

MODALITY: nonmodal-clause, true-modal-clause, future-clause

DO-INSERTION: do-inserted, no-do-inserted.

POLARITY: positive-polarity, negative-polarity.

PROCESS-TYPE: material-clause, verbal-clause, mental-clause, relational-clause.

VOICE: active-clause, passive-clause.

MOOD: declarative, imperative, interrogative.

A later research phase will further develop the range of syntactic features extracted, in particular, to enrich the

range of clause features recognised (e.g., clause transitivity patterns), and also for NPs, which our error annotation

work has shown to warrant much attention.

We parsed 1330 texts, containing 700,000 words, producing 98,000 clauses, and 150,000 NPs. The next question

is, given all this data, how do we use it to inform us about what students need to learn and when?

3. Using a learner corpus to inform curriculum design

It is relatively easy to use a learner corpus to see what learners need to be taught. A comparison between levels of

usage of vocabulary or syntactic features will reveal which lexis or syntactic features are under-used by a group of

learners, and thus where more teaching would be valuable, e.g., Granger (1997) on participle clauses, Dagneaux

(1995) on modal expressions.

A more difficult question involves determining when to teach lexis and grammar: where the foreign language is

taught over a number of levels, to which of these levels should particular lexical and grammatical concepts be

taught?

3.1. Levels of usage

One might look at levels of usage of structures over increasing proficiency levels. For instance, Figure 1 shows

how use of two grammatical features increase with proficiency. Passive clauses account for about 3% of clause in

our A1 learners, but this increases to around 9% by the time they reach C2 proficiency (note: these figures and all

figures given in the this paper relate to the essay-based nature of our learner corpus). The use of past-participle

1% of all clauses produced by A1 learners, up to nearly

3% by the C2 stage.

3,50%

3,00%

2,50%

2,00%

1,50%

1,00%

0,50%

0,00%

10,00%

8,00%

6,00%

4,00%

2,00%

0,00%

A1

A2

B1

B2

(a) passive voice

C1

C2

A1

A2

B1

B2

(b) past-participle

cause

Fig. 1: Increasing using of grammatical features with increasing proficiency

C1

C2

Mick ODonnell / Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 95 (2013) 571 580

575

This rising pattern is quite common over our learner corpus: beginning learners in general produce the simplest

structures possible to communicate ideas, and gradually learn the more complex variants: moving from active to

passive, from finite to nonfinite, from reporting simple actions to reporting more complex verbal and mental actions,

etc.

However, these diagrams by themselves do not give us a clear idea where it would be best to teach a particular

linguistic feature: learners are gradually increasing their usage of the feature, but there is no proficiency level where

we can say: this feature should be taught at this level.

3.2. Onset of use

A different way to use learner data to inform when to

looking at the degree of usage of particular features at each proficiency level, we rather ask whether particular

learners are using the structure at all. Our question is: are they capable of producing it? We thus observe, for each

learner essay, whether the essay contains any instance of the structure. We then graph the proportion of learners

which

use the structure against rising proficiency. For instance. Figure 2 shows the onset of use for pastparticiple clauses in our corpus, whereby roughly 14% of

all learners were using them.

15,00%

10,00%

5,00%

0,00%

A2

B1

B2

C1

C2

Fig. 2: Onset of use for past-participle

clauses

Such an approach allows us to see when structures should be taught. A good point to teach might be when early

adopters have started to use the structure (e.g., 20% of students are using it), but the more cautious learners have not

yet begun.

One problem with this approach is that one needs enough text from each learner to make it probably that the

structure would appear if they knew how. Passive clauses for instances are so common that it would be very

improbable that none would occur in a 1000 words essay. For this reason, we used a subsection of our corpus, using

only the Wricle texts, which are on average 1000 words long, ignoring the UPV corpus which are shorter. This

subcorpus lacks A1 texts, which is why Figure 2 has no column for A1.

However, many features of interest are far less common than the passive: the non-occurrence of a cleft sentence

in 1000 word essay does not necessarily indicate lack of ability in this structure.

limited to the more common features of the language.

Another problem relates to register restrictions in the corpus: the incidence of certain features is register specific.

For instance, mood tags (e.g., Y

You agree,

) only occur in spoken discourse, so will be absent in written

discourse. Lack of mood-tags in the corpus does not necessarily indicate the learners do not know how to produce

them.

576

Mick ODonnell / Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 95 (2013) 571 580

3.3. Criterial Features

Hawkins and Buttery (2009, 2010) have been doing interesting work, using a learner corpus composed of texts

written within proficiency exams. Their work attempts to

(Hawkins and

Buttery, 2010: 2). They say that

rties of English that are acquired at a

(p5).

However, when I try to examine our corpus from this approach, I find things are blurred. There are no features

which magically appear at a given level: onset of use is gradual, with some students at each level using the feature,

and some not. Acquisition does not happen suddenly between levels. Rather, in each successive L2 level, a higher

number of learners exhibit the feature. The question remains: how many learners need to exhibit the feature to say

that the feature is criterial for that level?

Given the gradual onset of use, I have not found a practical way to use the criterial features approach with our

corpus.

3.4. Ordering features in difficulty: using the usage vs. proficiency graph

Proficiency levels do not in truth exist: they are a convenience created by language professionals to enable us to

ratify our learners, and to provide target points for the teaching materials we provide.

Each language learner learns the foreign language in a unique manner, mastering linguistic concepts in their own

time and order. However, these linguistic concepts do, in general, offer more or less difficulty to learners, so when

we look at learners as a group, we do find that, more often than not, that concepts will be acquired in a certain order.

The particular order may differ in any one learner, but, taken as a whole, there is a tendency to a particular ordering

for a particular linguistic community. Note however that different linguistic communities may find certain concepts

more or less difficult than other linguistic communities. For instance, Spanish learners of English already have a

present-perfect structure, with overlapping conditions of use, so they have less trouble learning this structure than

those of mother tongues which lack present-perfect, or which have very different conditions of use. On the other

hand, Spanish learners have difficulties with English phrasal verbs, while German learners have less difficulty, as

they play a part in their mother tongue.

While it is difficult to use a learner corpus to assign linguistic features to proficiency levels, the corpus can be

used to discover the inherent order of acquisition of linguistic features, which I take here to relate to the order of

difficulty of these features.

In relation to the level of difficulty of linguistic features, I start with the following intuitive observations:

If a structure presents difficulty in acquisition, then it will be observed less frequently in beginners and rise in

frequency as proficiency advances. We would thus expect usage graphs as in Figure 3a, demonstrating a steady

rise in frequency as the learner progresses.

0,25%

4,00%

0,20%

3,00%

0,15%

2,00%

0,10%

1,00%

0,05%

0,00%

0,00%

A1

A2

B1

B2

C1

C2

Fig. 3a: Increasing usage of past-participle

clauses

A1

A2

B1

B2

C1

Fig. 3b: Falling usage off past--progressive aspect

C2

577

Mick ODonnell / Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 95 (2013) 571 580

2,50%

2,50%

2,00%

2,00%

1,50%

1,50%

1,00%

1,00%

0,50%

0,50%

0,00%

0,00%

A1

A2

B1

B2

C1

C2

Fig. 3c: Rise and ffall in the present-progressive aspect

A1

A2

B1

B2

C1

C2

Fig. 3d: Rise and fall in future-clause use.

If a structure presents no difficulty to a learner (it can be cleanly transferred from the mother tongue) then the

anguage as in advanced learners, or, even fall in frequency

(due to the learner replacing this structure with alternative expressions). An example of the latter case is shown in

figure 3b, showing learners move away from the use of past-progressive aspect as they gain in proficiency.

In some case, the usage graph presents an initial rise in usage, followed by a leveling or even falling (e.g., Figure

3c), suggesting a structure with slight difficulty of acquisition at low levels, but easlily handled by intermediate

levels. In the case of future-clauses, we think the fall in future tense is due to the learners acquiring alternative

Given these patterns, I have experimented with the following means of ordering features in difficulty:

1. Slope of the line of best fit: a positive slope of the line of best fit indicates that learners make more use of the

feature as they progress in proficiency. One interpretation of this increase is that the difficulty in using the

structure is overcome with greater proficiency. In some cases, the difficulty may not be in regards to

producing the structure, but in regards to knowing when it is appropriate. Stronger slopes indicate larger

differences between lower levels and higher levels, which could be taken to mean that the feature is more

difficult to acquire. Features which have a negatively sloped line of best fit, such as the present-progressive

above, indicate the learner acquires the feature early, and thus that the feature has low difficulty.

2. XX intercept of the line of best fit: the more difficult a structure, the later in proficiency that it will be acquired.

For difficult structures, we would thus expect few or no A1 or A2 hits. The X-intercept for the line of

tendency would thus be greater (indicating the point early adopters start using the structure).

4. Results : ordering lexical-grammatical features in terms of difficulty

To get some idea as to how the difficulty orderings of features relate to our intuitions, I will concentrate on the

ordering of tense-aspect features. Table 1 shows the tense-aspect features ordered in terms of increasing slope of the

line of best fit. Negative slow figures indicate the usage falls with rising proficiency. Positive slope values indicate

rising usage with proficiency.

Table 1. Tense-Aspect features ordered in terms of slope of line of best fit

578

Mick ODonnell / Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 95 (2013) 571 580

Tense-Aspect Feature

Slope

X-Intercept

simple-present

-0.00209

394

present-progressive

-0.00022

142

simple-future

-0.00014

266

present-progressive-perfect

0.00000

-3583

past-progressive

0.00000

-308

future-progressive

0.00000

-9

modal-progressive

0.00001

-118

past-perfect

0.00003

-7

modal-perfect

0.00003

20

present-perfect

0.00022

-80

simple-modal

0.00023

-191

simple-past

0.00063

-16

The ordering starts off well, suggesting Spanish learners of English start off with simple-present and presentprogressive as the first-acquired tenses, with simple-future soon after. The present-progressive-perfect comes next

seems more advanced than some tenses after. I note here that only 78 out of

98,000 clauses had this feature, and most of them occurred in the central proficiency levels, which make the exact

slope of the line somewhat doubtful, and perhaps this feature should be dropped from this list.

These initial features are followed by three progressive forms (past-progressive, future-progressive and modalprogressive), and then three perfect forms (past-perfect, modal-perfect and present-perfect), which is not outside of

the expected. Note however that the x-intercept for modal-perfect is 20, which suggests fairly late onset of use,

countering the positive slope value.

state

like

.) is the second last tense in the list. In this case, the slope value is

Simpledeceptive: while there is a fairly steep increase in usage in simple-modal between A1 level to C2 level (from 8% to

11.7%), the mitigating factor is that even A1 learners are using a lot of this feature. Examination of the x-intercept

value would have shown this, given an intercept of -191.

The last item in the list is simple-past. This is not a difficult tense to master in English, but it seems that more

n 1990 Spain settled the obligatory education up to

advanced essay are using past-tense to report past events

16 years. Again, the initially relatively high rate of usage of simple-past (3.84% at A1) indicate that mitigating

slope with knowledge of X-intercept might improve the ordering. In this case, there is learning going on as the

learner progresses in proficiency, but it is not learning how to produce the structure, but rather, learning how to

provide evidence for an argument, which in part results in more simple-past tense. We thus see that any results need

to be interpreted, not taken at face value.

Further work will experiment with deriving an order based on a formulaic combination of slope and x-intercept.

The same process can be applied to the other grammatical features recognized by the parser (and any additional

features we add in the future). Features that are indicated as easily acquired include: declarative-clause, finite-clause,

active-clause, no-do-insert and negative-clause, while those indicated as difficult include nonfinite-clauses and

passives.

We have applied the same approach to our error-tagged corpus, and the results for lexical-errors were particularly

interesting, with all transfer-induced errors (coinage, false-friends, transferred-spelling) indicated as being stronger

in beginning learners, with non-transfer errors more common in the higher level learners.

Mick ODonnell / Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 95 (2013) 571 580

579

5. Towards a corpus-informed grammatical curriculum

Given a list of grammatical concepts sequenced by difficulty, we can divide this list into equal-size subsets to be

taught in each course within the sequence of courses in the degree. For instance, assuming we teach our degree in

terms of five semesters of classes, we might split the content into 5 distinct chunks, as shown in Figure 4.

Fig. 4: Dividing the order-feature list into distinct packets for levels

However, prior to splitting the list, some shifting around of concepts might help, to ensure that thematically

related concepts are taught in the same course. An optimisation algorithm might be built, rewarding keeping certain

concepts together but penalising moving concepts too far from their initial position. The collections of concepts then

assigned to each class would then be more thematical coherent.

6. Conclusions

It should be clear that the results of both error annotation and syntactic annotations can reveal what aspects of a

second language are critical for students need to learn. Analysis of errors can highlight those aspects of the language

that trouble the student, and thus where explicit teaching can help. Equally so, comparison between learner language

and native language can reveal where learners are over-using or under-using particular vocabulary or structures.

However, the problems revealed by analysis of learner corpora are not clearly associated with particular levels of

learner proficiency. As such, it is difficult to decide exactly how the features identified by the corpus study should be

placed into a foreign language teaching curriculum.

In this paper, I have argued that, while we cannot use the corpus to unequivocally place linguistic features into

proficiency levels, we can however use our data to order these features relative to each other in terms of order of

acquisition, which might be related to levels of difficulty of the concepts involved.

This paper has explored various methods in which this ordering could take place, in particular, suing the slope of

the line of best fit, and also using the point of intersection of this line with the x-axis. I concluded that a formula that

combined these two values to produce a single ordering would be best, whereby features later in this list are best

taught later.

Using this method, we then explore ways to apply the ordering of linguistic features by difficulty to curriculum

design. A first simple method of splitting the ordered list into a number of sub-lists, each corresponding to one

course in the set of courses that compose the programme.

A refinement was suggested whereby, before splitting the list, some shuffling of grammar concepts is done, to

bring together those linguistic concepts which are conceptually related. The cost of moving concepts in the list can

be varied, higher costs keeping concepts together in terms of their difficulty, lower costs allowing more thematic

organisation.

References

Andreu, M., Astor, A., Boquera, M., MacDonald, P., Montero, B. & Prez, C. (2010). Analysing EFL learner output in the MiLC project: An

In M.C. Campoy, B. Belles-Fortuno & M.L. Gea-Valor (Eds.), Corpus-Based Approaches to English Language

Teaching (pp. 167-179). London: Continuum.

Dagneaux, E. (1995). Expressions of Epistemic Modality in Native and Non-native Essay Writing. M.A. Dissertation, Louvain-la-Neuve:

Universit catholique de Louvain.

580

Mick ODonnell / Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 95 (2013) 571 580

Dez-Bedmar, M.B. (2010). From secondary school to university: The use of the English article system by Spanish learners. In B. Bells-Fortuo,

M.C. Campoy-Cubillo & M.L. Gea-Valor (Eds.), Exploring corpus-based research in English language teaching (pp. 45-55). Castell de la

Plana: Publicacions de la Universitat Jaume I.

English Profile (2012). What is English Profile?. Website: http://www.englishprofile.org/. Accessed: January, 2012.

Granger, S. (1997). On identifying the syntactic and discourse features of participle clauses in academic english: native and non-native writers

compared. In J. Aarts, I. de Mnnink & H. Wekker (Eds.), Studies in English Language and Teaching (pp. 185-198). Rodopi: Amsterdam &

Atlanta.

Granger, S. (1999). Use of tenses by advanced EFL learners: evidence from an error-tagged computer corpus. In H. Hasselgard & S. Oksefjell

(Eds.), Out of Corpora- Studies in Honour of Stig Johannson (pp. 191-202). Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Hawkins J.A. & Buttery, P. (2009). Using learner language from corpora to profile levels of proficiency: Insights from the English Profile

Programme. In L. Taylor & C. Weir (eds.), Studies in Language Testing: The Social and Educational Impact of Language Assessment (pp.

158-175). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hawkins J.A. & Buttery, P. (2010). Criterial Features in Learner Corpora: Theory and Illustrations. English Profile Journal, 1 (1), 1-23.

Klein, D. & Manning, C. (2003). Fast Exact Inference with a Factored Model for Natural Language Parsing. In S. Becker, S. Thrun & K.

Obermayer (Eds.), Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 15 (NIPS 2002) (pp. 3-10). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Meunier, F. (2002). The pedagogical value of native and learner corpora in EFL grammar teaching. In S. Granger, J. Hung & S. Tyson (Eds),

Computer learner corpora, second language acquisition and foreign language teaching (pp. 119-142). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins.

O'Donnell, M. (2008). Demonstration of the UAM CorpusTool for text and image annotation. In Proceedings of the ACL-08:HLT Demo Session

(Companion Volume), Columbus, Ohio, June, 2008 (pp. 13 16). Association for Computational Linguistics.

O'Donnell, M. (2012). Using learner corpora to redesign university-level EFL Grammar education. Revista Espaola de Lingstica Aplicada

(RESLA), Vol. Extra 1, 2012. 145-160.

O'Donnell, M., Murcia, S., Garca, R., Molina, C., Rollinson, P., MacDonald, P., Stuart, K., & Boquera, M. (2009). Exploring the proficiency of

English learners: The TREACLE project. In M. Mahlberg, V. Gonzlez-Daz & C. Smith (Eds.), Proceedings of the Fifth Corpus

Linguistics, Liverpool.

Rankin, T. (2010). Advanced learner corpora data and grammar teaching: adverb placement. In M.C. Campoy, B. Belles-Fortuno & M.L. GeaValor (Eds.), Corpus-Based Approaches to English Language Teaching (pp. 205-215). London: Continuum.

Rollinson, P. & Mendikoetxea, A. (2010). Learner corpora and second language acquisition: Introducing WriCLE. In J. L. Bueno Alonso, D.

Gonzliz lvarez, U. Kirsten Torrado, A. E. Martnez Insua, J. Prez-Guerra, E. Rama Martnez & R. Rodrguez Vzquez (Eds.), Analizar

datos: Describir variacin/Analysing data: Describing variation (pp. 1-12). Vigo: Universidade de Vigo (Servizo de Publicacins).

UCLES (2001). Quick Placement Test (Paper and pencil version). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Using Authentic Videos To Improve EFL Students' Listening ComprehensionДокумент10 страницUsing Authentic Videos To Improve EFL Students' Listening ComprehensionDiah Puspita WulanОценок пока нет

- Differences Between Addie Model and Assure ModelДокумент3 страницыDifferences Between Addie Model and Assure ModelRaafah Azkia AR86% (7)

- Esl Reports Summer Camp April 2015Документ9 страницEsl Reports Summer Camp April 2015Vijaya ThoratОценок пока нет

- BES Corrected ACCOMPLISHMENT REPORT ON GENTRI SINuLIDДокумент3 страницыBES Corrected ACCOMPLISHMENT REPORT ON GENTRI SINuLIDMhalou Jocson EchanoОценок пока нет

- Study of Maeterlinck's Interior in The Light of AbsurdityДокумент9 страницStudy of Maeterlinck's Interior in The Light of AbsurdityLeonardo MunkОценок пока нет

- Thematic AnalysisДокумент11 страницThematic AnalysisTruc PhanОценок пока нет

- Social Studies SBAДокумент22 страницыSocial Studies SBASamantha Seegobin73% (11)

- English: Quarter 1, Wk.3 - Module 4Документ32 страницыEnglish: Quarter 1, Wk.3 - Module 4Paity Dime100% (2)

- ETech Q1 Module-2Документ21 страницаETech Q1 Module-2Blessy QuimnoОценок пока нет

- Facebook Demographics 2009Документ17 страницFacebook Demographics 2009gdrouin15Оценок пока нет

- Indoor Outdoor Advertising 23 Marketing Arjun GillДокумент30 страницIndoor Outdoor Advertising 23 Marketing Arjun Gillkabhijit04100% (1)

- Rancangan Pengelolaan Interaksi Media Sosial Selasar Sunaryo Art Space Kota BandungДокумент7 страницRancangan Pengelolaan Interaksi Media Sosial Selasar Sunaryo Art Space Kota BandunglalaОценок пока нет

- RPT Bi OctДокумент2 страницыRPT Bi OctleeyaОценок пока нет

- Brahmdutt Upraity: Career ObjectiveДокумент2 страницыBrahmdutt Upraity: Career ObjectiveBRAHAMDUTT UPRAITYОценок пока нет

- Workforce Development Model For Patient & Public InvolvementДокумент38 страницWorkforce Development Model For Patient & Public InvolvementPaul ByrneОценок пока нет

- Assignment-W2 Nptel NotesДокумент6 страницAssignment-W2 Nptel NotesAshishОценок пока нет

- Building Bridges Across Social Science Discipline 2021-2022 MIDTERM EXAMДокумент2 страницыBuilding Bridges Across Social Science Discipline 2021-2022 MIDTERM EXAMFobe Lpt NudaloОценок пока нет

- Kajian Tindakan Tesl Chapter 1Документ17 страницKajian Tindakan Tesl Chapter 1MahfuzahShamsudin100% (1)

- E-Book - Principles-of-Marketing-1613761555Документ4 страницыE-Book - Principles-of-Marketing-1613761555Geo GlennОценок пока нет

- Lesson Plan Two Individual Beowulf Multimedia CollageДокумент2 страницыLesson Plan Two Individual Beowulf Multimedia Collageapi-533090223Оценок пока нет

- 2 - Discourse and Society-1Документ16 страниц2 - Discourse and Society-1Han D-RyОценок пока нет

- Key Principles of Curriculum Alignment - AUN 2016Документ2 страницыKey Principles of Curriculum Alignment - AUN 2016cunmaikhanhОценок пока нет

- LinguisticДокумент15 страницLinguisticRomina Gonzales TaracatacОценок пока нет

- Ch. 14 Second Language Acquisition-LearningДокумент7 страницCh. 14 Second Language Acquisition-Learningمحمد ناصر عليويОценок пока нет

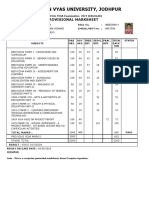

- Jai Narain Vyas University, Jodhpur: Provisional MarksheetДокумент1 страницаJai Narain Vyas University, Jodhpur: Provisional MarksheetTushar KiriОценок пока нет

- World Class 1 Student Book 181108183750 PDFДокумент5 страницWorld Class 1 Student Book 181108183750 PDFRonald MaderaОценок пока нет

- FS1 Semi FinalsДокумент16 страницFS1 Semi FinalsAsh LafuenteОценок пока нет

- WHLP in Oral Comm - Week # 3Документ2 страницыWHLP in Oral Comm - Week # 3Lhen Unico Tercero - BorjaОценок пока нет

- 02 SejongFacultyProfiles 20131209Документ143 страницы02 SejongFacultyProfiles 20131209Luong Tam Thinh0% (2)

- Lesson 6Документ3 страницыLesson 6api-530217551Оценок пока нет