Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Rise of Female Professionals

Загружено:

adamИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Rise of Female Professionals

Загружено:

adamАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

American Economic Association

The Rise of Female Professionals: Are Women Responding to Skill Demand?

Author(s): Sandra E. Black and Chinhui Juhn

Source: The American Economic Review, Vol. 90, No. 2, Papers and Proceedings of the One

Hundred Twelfth Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association (May, 2000), pp. 450455

Published by: American Economic Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/117267 .

Accessed: 22/01/2015 17:45

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

American Economic Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The

American Economic Review.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 129.93.16.3 on Thu, 22 Jan 2015 17:45:27 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Rise of Female Professionalsu

Are Women Responding to Skill Demand?

By

SANDRA E. BLACK AND CHINHUI JUHN*

For years, college-educatedwomen were limited mainly to lower-paying, female-dominated

professions such as teaching and nursing. Over

the past several decades, however, there has

been a remarkableincrease in the percentageof

college-educatedwomen in higher-paying,"traditionally male" professional occupations. In

1967, the fraction of college-educated women

working in these occupations was less than 20

percent. By 1997, this numberhad increasedto

almost 40 percent. This increase is particularly

striking when compared to the slightly declining trend among college-educated men.

What can explain this increase in female professionals? There are a numberof possible explanations. One explanation is a demand shift

favoring women over men in these highly

skilled occupations. While the notion of a

6"gender-specific"demandshift is compelling in

the case of high-school-graduate men and

women, who work in very different industries

and occupations,the story is much less convincing for the college-educated group. Collegeeducatedmen and women work in more similar

occupations and are presumably closer substitutes for each other. To the extent that they are

different, the available evidence suggests that

this may have worked to the disadvantage of

women (see FrancineBlau and LawrenceKahn,

1997).

Anotherexplanation,andthe one we focus on

in this paper, is that college-educated women

have responded to the rise in overall skill demand, a phenomenon which has characterized

the U.S. labor market during the 1980's and

* Black: FederalReserve Bank of New York, 33 Liberty

Street, New York, NY 10045 (e-mail: sandra.black@

ny.frb.org);Juhn:Departmentof Economics, University of

Houston, Houston, TX 77204 (e-mail: cjuhn@uh.edu).We

thank Nate Baum-Snow and Amir Sufi for their excellent

researchassistance. The views expressed here are those of

the authorsand do not necessarily reflect the views of the

FederalReserve Bank of New York or the FederalReserve

System.

perhapseven as early as the 1970's. An important margin of response for these women may

have been labor-marketparticipation.In 1970,

less than 60 percentof college-educatedwomen

were working. The economy-wide rise in skill

demand may have attracted educated women

not only from other occupations,but from nonparticipationas well. Since virtually all college

educated men work, labor-marketparticipation

is less likely to be a factor for men.

While we postulate that the overall increase

in skill demandplayed an importantrole, we are

also aware that this is not the only explanation.

Within these high-wage professional occupations, women's wages rose relative to male

wages even as women increased their share.

This suggests to us that declining discrimination

(which both made it easier for women to enter

these occupations and resulted in wage convergence vis 'avis the male workers)or unobserved

skill upgradingalso may have played a role. In

addition, the spread of more effective birthcontrol devices, Roe v. Wade, and no-fault di

vorce laws, just to name a few of the factors

which changedmarriageand fertilitypatternsof

women, also most likely contributedto women's willingness and ability to invest in "career

jobs" (see Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz,

2000).

1 The Rise of P'emale Professionals

ad Manager

We use the March Supplementto the 19681998 Cufrent Population Surveys (CPS), with

eamings and employment data covering the

years 1967-1997. We limit the sample to indi

viduals aged 25-64 to avoid many of the issues

related to the completion of schooling and retirement.When examining wages, we focus on

wages and salaries of full-time workers who

worked at least 40 weeks during the previous

year. Our wage measure is weekly wages calculated as earningsin the previous year divided

by weeks worked in the previous year. Individ-

450

This content downloaded from 129.93.16.3 on Thu, 22 Jan 2015 17:45:27 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

VOL.90 NO. 2

WOMEN'SLABOR-MARKET

GAINS

uals must be earningat least half of the weekly

equivalentof the minimumwage to be included

in the wage sample.

We focus on professionalsas a share of total

population, defined by gender and education.

Thus, our main variable of interest can be interpreted as "participationin professional occupations," which reflects both labor-market

participationdecisions and occupationalchoice.2

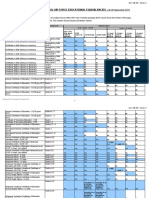

The top panels of Table 1 document the rise

in professionals, first among all women and

then among college women. In 1967, approximately 9 percent of women were working as

professionalsand managersand less than 5 percent were employed in professional occupations, excluding teachers and nurses. Recently,

the fractions of women in these occupations

have increased to 29 percent and 22 percent,

respectively. We also see a large increase when

we look at college-educated women only.

Figure 1 shows the fractions of professional

college women indexed to their 1967 values. As

the figure illustrates, the changes are particularly pronouncedfor our altemative definitions

of professionalsthat eitherexclude teachersand

nurses or that are defined as "high-wage"based

on male wages.3The fractionof broadlydefined

professionalwomen increasedslightly while the

fraction of college women who are in profes-

1 In addition,we adjustfor top-codedearningsby gender

and impute weeks worked within brackets for 1967-1974.

Details are available from the authorsupon request. A key

limitation of the CPS data is the omission of actual labormarketexperience. We use potential experience calculated

as age minus years of schooling minus 6 to proxy for

labor-marketexperience.

2 We focus on professionals as a share of population

rather than the employed population because we believe

that, for many college women, the decisions to enter the

labor market and to enter a professional occupation are

inextricablylinked. For this reason, we also use changes in

the level of professional wages for women, rather than

relative wages, later in our regressions. To align our employment variables with the earnings information,we calculate the fraction of the populationwho are professionals

by dividing total professionalweeks worked by total potential weeks worked last year (52 X numberof individuals).

3 More precisely, we rank occupations at the three-digit

SIC level based on male wages (cofrected for experience)

and select the highest-wageoccupationsin which 20 percent

of the men are employed. While coding changes make it

difficult to hold this definitionconstantacross all years, we

fix the top occupations over the following periods: 19671969, 1970-1981, and 1982-1997.

451

TABLE 1-PROFESSIONALSAS SHAREOF POPIJLATION

OVERTIME

Year

Sample

1967 1977 1987 1997

All women

Professionals

0.089 0.130 0.213 0.286

Professionals excluding

0.049 0.080 0.154 0.219

nurses and teachers

Professionals in high-wage 0.034 0.041 0.081 0.109

occupations

College women

Professionals

0.442 0.483 0.554 0.592

Professionals excluding

0.158 0.222 0.329 0.397

nurses and teachers

Professionals in high-wage 0.080 0.104 0.186 0.235

occupations

All men

Professionals excluding

nurses and teachers

0.256 0.271 0.285 0.296

College men

Professionals excluding

nurses and teachers

0.656 0.630 0.617 0.620

Notes: A workeris defined as being a professional if he or

she is classified as a manageror professionalin the previous

year. The high-wage-occupations variable represents the

number of women employed in the occupations with the

highest average male wages (see text for details).

Source: CurrentPopulationSurvey, 1968-1998.

sional occupations (excluding teachers and

nurses) increased by a factor of 2.5 and the

fraction of college women in high-wage male

occupations increased almost threefold. We focus on the professional share that excludes

teachersand nurses, since this category exhibits

dramaticchanges and yet is fairly straightforwardto calculate.We will referto this category

as "traditionally male" professional occupations. In sharp contrast to the rising share of

female professionals,there has been a declining

trend for men. The share of college-educated

men in professional occupations declined

slightly from approximately66 percent to 62

percent (see last row of Table 1).

Figure 2 illustrates the share o-f collegeeducated women working in "traditionally

male" professional occupations disaggregated

by birth cohort. We can roughly identify three

groups of cohorts, which exhibit very different

patterns.The oldest generation,women born before 1930, exhibitlittleincreasein participationin

"traditionallymale" professional occupations.

This content downloaded from 129.93.16.3 on Thu, 22 Jan 2015 17:45:27 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

452

AEA PAPERSAND PROCEEDINGS

MAY2000

0.45

C

0.40

'

0.35 +

0.30

L_

2.5-

0.250.0

1967

1971

I-Professionals

1975

-Excluding

1979

1983

Year

1987

Nurses and Teachers -High

1991

1995

Wage Occupabons!

0.10c

27

32

37

42

47

52

57

62

Age

FIGURE1. PROFESSIONALS/POPULATION,

COLLEGEEDUCATEDWOMEN(INDEXED:1967 = 1)

Notes: See text for details.

Source: CurrentPopulation Survey, 1968-1998.

Birth Cohort:

-_- 1905-1909

-1910-1914

--1915-1919

-1920-1924

- 1925-1929

_.1930-1934

+1935-1939

-1940-1944

-1945-1949

1950-1954

-.1955-1959

1960-1964

-1965-1969

-

FIGURE2. PROFESSIONALS/POPULATION,

COLLEGEEDUCATEDWOMEN

While these women increasedtheirlaborsupply

overall, they appearto have predominantlylocated to less-skilled occupations.

The second group of women, women born

between 1930 and 1955 significantlyincreased

their participationin professional occupations

over their lifetimes.4 Interestingly,a large fraction of these women began their careers with

high participationrates in teaching and nursing

occupations (the very occupationswe excluded

in the previous figure) and decreasedtheir participation in these occupations over their lifetime. For example, among the cohort born in

1945-1949, 33 percentwere employed in teaching and nursing at age 25-29. At age 40-44,

only 27 percent were employed in these occupations, while 35 percent were employed in

"traditionallymale" professional occupations.

This suggests thatthereare changes in the composition of employment, even within cohorts,

for these women.

The finalgroupof women,the groupbornafter

1955, begin theircareersat high levels of participationin "traditionally

male"professionaloccupations. The absence of aging effects for these

women is quite striking.While furtherinvestigation is needed,we surmisethatthese are the generationsof women who chose the "career,then

family"pathdocumentedin Goldin(1997). There

4This is the case even when we allow for aging and

experience effects based on male professionalparticipation

rates.

Notes:See text for details.

Source: CurrentPopulationSurvey, 1968-1998.

are two opposingeffects thattend to cancel each

other as these women age. On the one hand,

accumulationof experience,completionof training, and promotionswill increasethe fractionin

high-wageprofessionaloccupations.On the other

hand, these women are also reducingtheir labor

supply as they invest in family and children,

which tends to decreasethe fractionworking in

professionaloccupations.We do indeed find that

the employment-population

ratio among women

born in 1960-1964, for example, declined from

84 percent at age 25-29 to 77 percent at age

30-34.

II. CollegeWomenand Skill Demand

We next examine whetherthe rising share of

women in "traditionallymale" professional occupationsis related to the recently documented

increase in demand for skill. We postulate that

women, and particularly college-educated

women, are likely to have a more elastic response to increased skill demand relative to

their male counterparts.As mentioned before,

an importantmargin of response available to

women but not to men (who are all already in

the labor force) may be labor-marketparticipation. This argument holds not only for rising

professional share within cohorts, but also for

the rising shareacross birthcohorts.Since these

This content downloaded from 129.93.16.3 on Thu, 22 Jan 2015 17:45:27 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

high-wage professionaloccupationsmost likely

involve "career"investments in human capital

which can only be recouped by working for

many years, the recent increase in skill demand

may have attractedwomen from a "career"of

nonparticipationas well as careersin less skillintensive occupations.

We first examine within-cohort growth in

professionalshare and its relationto rising skill

demand by estimating the following equation:

(1)

Patf-

453

WOMEN'SLABOR-MARKET

GAINS

VOL.90 NO. 2

3Wat

+ 6a

+ Tc + eat

TABLE2-WITHIN-COHORTESTIMATES

OF PROFESSIONALLABOR-SUPPLY

ELASTICITIES

FORWOMEN

A. College-EducatedWomen

Specification

Variable

Partialelasticity

5 Our methods and instrumentsare similar to those employed by John Pencavel (1998).

(ii)

(iii)

(iv)

0.004

0.046 -0.291

0.332

(0.012) (0.013) (0.149) (0.127)

Five-year cohort

dummies

yes

no

yes

no

Ten-year cohort

dummies

no

yes

no

yes

Instlumentfor wage

where Pat is the fraction of the population of

age a and at year t working in "traditionally

male" professional occupations, Wat is the

average log wage of individuals of age a and

at year t working in these occupations,1a refers

to age effects capturedby a quarticfunction in

age, Tc refers to cohort effects and Sat refers to

the error term. We aggregate data up to the

age-by-year cell and then run weighted leastsquares regressions where the weights are the

number of individuals in each cell. There are

1,240 observationsthatdiffer by 40 single years

of age (25-64) and 31 years (1967-1997). To

distinguishbetween effects of skill demandand

changing discrimination(as well as to correct

for endogeneity of wages), we instrumentwage

growth with the level of real merchandiseimports and its interactionswith age variables in

some of the specifications.5

Table 2 reportsthe estimatesof within-cohort

professional (partial) labor-supply elasticities

for women. The top panel reportsthe results for

college-educated women, while the bottom

panel reports the results for all women. Columns (i), (ii), (v), and (vi) do not instrumentfor

the wage, while columns (iii), (iv), (vii), and

(viii) use the level of real merchandiseimports

and interactionswith the age variablesas instruments for the wage. The table shows that, overall, the within-cohort correlations are more

positive and robust for all women than for college women and more robust when we specify

ten-year cohort dummies than five-year cohort

dummies.In fact, when we look only at college

(i)

N:

R2:

no

no

yes

yes

1,240

0.797

1,240

0.749

1,240

0.705

1,240

0.654

B. All Women

Specification

Variable

Partialelasticity

(v)

(vi)

(vii)

(viii)

0.354

0.015

0.058

0.527

(0.006) (0.008) (0.098) (0.094)

Five-year cohort

dummies

yes

no

yes

no

Ten-year cohort

dummies

no

yes

no

yes

for wage

Instrunment

no

no

yes

yes

1,240

0.941

1,240

0.891

1,240

0.795

1,240

0.593

N:

R2:

Notes: Standarderrors are in parentheses.The dependent

variableis the fractionof the respective populationwho are

professionals(excluding teachersand nurses).Ihe independent variableis the average wage of professionals (excluding teachersand nurses).All specificationsinclude a quartic

in age as well as the reportedcohort effects. Instrumented

regressionsuse the level of real merchandiseimportsand its

interactionswith age variables.

women, specify five-year cohort dummies, and

instrumentfor the wage, the coefficient is actually negative (-0.29) and marginally significant. We also ran correspondingregressionsfor

all men and for college-educatedmen andfound

the estimates to be generally insignificant or

6

negative.

The fact that the estimates in Table 2 are

more positive when we use broadercategories

of cohorts (thereby allowing some between6The resultsare availablefrom the authorsupon request.

This content downloaded from 129.93.16.3 on Thu, 22 Jan 2015 17:45:27 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

454

AEA PAPERSAND PROCEEDINGS

cohort variation) is instructive. The results in

Table 2 suggest that, while women's response

to rising skill demand may be greater than

men's, the within-cohortresponseto rising skill

demandis limited, and much of the response we

are attempting to capture is exhibited across

birthcohorts.While we are hinderedby lack of

a convincing measureof skill demandover this

extendedperiod, we examine the correlationsof

predicted lifetime professional wages and predicted lifetime professional participationrates

across differentcohortsof college women in the

following section.

To obtainpredictedlifetime professionalparticipationrates and wages for each birthcohort,

we use the following predictingequation:

(2)

Pat,) Wat =

Ba + Tc +

sat

where Pat refers to the fraction employed in

"traditionallymale" professional occupations,

wat is the average log weekly wage in these

occupations, Sa refers to a quarticin age as well

as cohort-specific age splines for ages 25-29,

and Tc now refers to the set of single-year

cohort dummies. We predict Pat and wat for

each single-yearbirthcohortfrom 1915 to 1969

at each age and average across ages to obtain

the predicted"lifetime"participationin professional occupationsand predicted"lifetime"professional wages.7

Figure 3 graphs these variables by birth cohort for college-educated women. There is

clearly a strong positive relationship between

these two variables, reflecting the strong upward trend in both wages and participationof

college-educated women. The positive correlation persists even when we control for a trend.

The positive correlationin the detrendedseries

appearsto be driven by below-average growth

rates for the older cohorts and above-average

growthrates for the recent cohorts.The positive

correlationacross cohorts suggests that collegeeducated women have moved into high-wage

professionaloccupationsin response to increasing opportunitiesin these professions. Since we

7 This method producedvery similar results to the alternative method of extractingthe coefficients on cohort dummies, controlling for a quarticfunction in age.

MAY2000

.0.6

6.710

6.62

0.5

6.54

0.4

6.46

0.3

6.3.8

0 .2

6.30

0.1

-

6.22

1915 1920

1925

1930

1935

1940

1945

1950

1955

1960

0.0

1965

Birth Cohort

[- Log Weekly Wage

- Professional Share

FIGURE3. PREDICTED

LIFETIME

PARTICIPATION

(RIGHT-HANDAxis) AND WAGE (LEFT-HANDAxis)

IN PROFESSIONAL

OCCUPATIONS,

COLLEGE-EDUCATED

WOMEN

Source: CurrentPopulationSurvey, 1968-1998.

are examining actual wages rather that wages

that are correlatedwith overall skill demand,it

is less clear that these increasing opportunities

were directlyrelatedto skill demandratherthan

reductionsin discrimination.We do not think it

is entirely a coincidence, however, that discrimination against educated women lessened during a period of rising skill premiums. An

interestingcontrastis the evolution of race and

ethnic differentials which, unlike differences

across gender, have widened in the recent

period.

III. Conclusion

In this paper, we first document the rise in

female professionalsand managersin the recent

decades and then examine to what extent this

increase is associated with rising skill demand

in the 1980's and the 1990's. Overall, we find

that college women's participation in highwage professionaloccupationsis positively correlated with wages in these professional

occupations and our proxy measures for skill

demand. However, these positive correlations

are more robust across different birth cohorts

than within cohorts. For college-educated men,

we find a negative or no relationshipboth within

and across birth cohorts. Our analysis offers

some evidence that college-educated women

entered high-wage professional occupations in

response to the recent increase in skill demand.

Our analysis also confirms the view that career

and participationdecisions of women are com-

This content downloaded from 129.93.16.3 on Thu, 22 Jan 2015 17:45:27 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

VOL.90 NO. 2

WOMEN'SLABOR-MARKET

GAINS

plex and that no single explanationis likely to

account for the recent changes.

REFERENCES

Blau, Francineand Kahn,Lawrence."Swimming

Upstream:Trendsin the GenderWage Differentialin the 1980s."Journalof LaborEconomics, January1997, 15(1), Part 1, pp. 1-42.

Goldin, Claudia. "Careerand Family: College

Women Look to the Past," in F. Blau and

455

R. Ehrenberg,eds., Gender andfamily issues

in the workplace. New York: Russell Sage

FoundationPress, 1997.

Goldin, Claudia and Katz, Lawrence. "Career

and Marriagein the Age of the Pill." American Economic Review, May 2000 (Papers

and Proceedings), 90(2), pp. 461-65.

Pencavel, John. "The Market Work Behavior

and Wages of Women 1975-94." Journal of

HumanResources, Fall 1998, 33(4), pp. 771804.

This content downloaded from 129.93.16.3 on Thu, 22 Jan 2015 17:45:27 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Effectiveness of Multigrade Instruction in Lined With The K To 12 Curriculum StandardsДокумент7 страницEffectiveness of Multigrade Instruction in Lined With The K To 12 Curriculum StandardsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyОценок пока нет

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- Project SAGIPДокумент7 страницProject SAGIPHardy Misagal100% (2)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Pablo Picasso Print - BiographyДокумент3 страницыPablo Picasso Print - BiographyFREIMUZIC100% (1)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (894)

- Big Shoes To FillДокумент5 страницBig Shoes To FillRahul Tharwani100% (5)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Palmer, A Fashion Theory Vol 12 'Reviewing Fashion Exhibitions'Документ6 страницPalmer, A Fashion Theory Vol 12 'Reviewing Fashion Exhibitions'Tarveen KaurОценок пока нет

- Toy Designers Task Sheet and RubricДокумент2 страницыToy Designers Task Sheet and Rubricapi-313963087Оценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Effectiveness of Gamification in The Engagement of Students PDFДокумент16 страницEffectiveness of Gamification in The Engagement of Students PDFDuannNoronhaОценок пока нет

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Sperber Ed Metarepresentations A Multidisciplinary PerspectiveДокумент460 страницSperber Ed Metarepresentations A Multidisciplinary PerspectiveHernán Franco100% (3)

- Different Organizations and Associations of Management in The PhilippinesДокумент2 страницыDifferent Organizations and Associations of Management in The PhilippinesYhale DomiguezОценок пока нет

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- My Children Have Faces: by Carol Campbell Student GuideДокумент5 страницMy Children Have Faces: by Carol Campbell Student Guideapi-293957469Оценок пока нет

- 20170927-Ap3391 Vol3 Lflt205 Education Annex C-UДокумент8 страниц20170927-Ap3391 Vol3 Lflt205 Education Annex C-URiannab15Оценок пока нет

- 3962 PDFДокумент3 страницы3962 PDFKeshav BhalotiaОценок пока нет

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Pagasa LetterДокумент4 страницыPagasa LetterRuel ElidoОценок пока нет

- Lp2 (Tle7) CssДокумент4 страницыLp2 (Tle7) CssShiela Mae Abay-abayОценок пока нет

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Anti Ragging 2019Документ1 страницаAnti Ragging 2019GANESH KUMAR B eee2018Оценок пока нет

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- General Chemistry For Engineers (01:160:159) General Information, Fall 2014Документ11 страницGeneral Chemistry For Engineers (01:160:159) General Information, Fall 2014Bob SandersОценок пока нет

- Mardi Gras Lesson PlanДокумент1 страницаMardi Gras Lesson Planapi-314100783Оценок пока нет

- Cebu City Government Certification ExpensesДокумент4 страницыCebu City Government Certification ExpensesAilee Tejano75% (4)

- Michelle Johnson ResumeДокумент5 страницMichelle Johnson Resumemijohn4018Оценок пока нет

- Report of The Fourth Project Meeting SylvieДокумент3 страницыReport of The Fourth Project Meeting SylvieXAVIERОценок пока нет

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Resume Curphey JДокумент2 страницыResume Curphey Japi-269587395Оценок пока нет

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- Cycles of DevelopmentДокумент16 страницCycles of DevelopmentJackGalt100% (1)

- Construction Contract Administration TOCДокумент2 страницыConstruction Contract Administration TOCccastilloОценок пока нет

- Recommendation Letter 1Документ1 страницаRecommendation Letter 1api-484414371Оценок пока нет

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Eng102 APA Parallelism ModifiersДокумент71 страницаEng102 APA Parallelism ModifiersjeanninestankoОценок пока нет

- Learn CBSE: NCERT Solutions For Class 12 Flamingo English Lost SpringДокумент12 страницLearn CBSE: NCERT Solutions For Class 12 Flamingo English Lost SpringtarunОценок пока нет

- Prebstggwb 5 PDFДокумент14 страницPrebstggwb 5 PDFKabОценок пока нет

- LAUDE, J FS1 Activity 1Документ8 страницLAUDE, J FS1 Activity 1Honey FujisawaОценок пока нет

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Class Record BlankДокумент13 страницClass Record BlankEstrellita SantosОценок пока нет

- Lesson Plan Form MontessoriДокумент13 страницLesson Plan Form MontessoriCarlos Andres LaverdeОценок пока нет