Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

252 - Pagtalunan v. Tamayo

Загружено:

Aiken Alagban Ladines100%(1)100% нашли этот документ полезным (1 голос)

455 просмотров3 страницыcivpro

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

DOC, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документcivpro

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате DOC, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

100%(1)100% нашли этот документ полезным (1 голос)

455 просмотров3 страницы252 - Pagtalunan v. Tamayo

Загружено:

Aiken Alagban Ladinescivpro

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате DOC, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 3

CIVIL PROCEDURE Rule 19, Intervention.

PAGTALUNAN VS. TAMAYO (1990)

Petitioners: CELSO PAGTALUNAN and PAULINA P. PAGTALUNAN; Respondents: HON. ROQUE A. TAMAYO,

Presiding Judge of the CFI of Bulacan, Branch VI, REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES and TURANDOT, TRAVIATA,

MARCELITA, MARLENE PACITA, MATTHEW and ROSARY, all surnamed ALDABA; Ponente: CORTES, J.

Doctrine: Intervention is not a matter of right but may be permitted by the courts when the applicant

shows facts which satisfy the requirements of the law authorizing intervention. Under the Rules of Court,

what qualifies a person to intervene is his possession of a legal interest in the matter in litigation, or in the

success of either of the parties, or an interest against both, or when he is so situated as to be adversely

affected by a distribution or other disposition of property in the custody of the court or an officer thereof.

Such interest must be actual, direct and material, and not simply contingent and expectant.

Facts (Procedure in bold text):

1. [CFI of Bulacan] Respondent Republic of the Philippines filed a complaint for expropriation of a

parcel of land located in Bo. Tikay, Malolos, Bulacan, and owned by the Aldabas (as evidenced by a TCT

issued by the Register of Deeds of the province of Bulacan).

2. [CFI of Bulacan] The CFI issued a writ of possession placing the Republic in possession of the land,

upon its deposit of P7,200.00 as provisional value of the land.

3. [CFI of Bulacan] Petitioners (sp. Pagtalunans) filed a supplemental motion for leave to intervene,

with complaint in intervention attached thereto, alleging that petitioner Celso Pagtalunan has been

the bona fide agricultural tenant of a portion of the land. Petitioners asked the trial court to order payment

to Celso Pagtalunan of just compensation for his landholding or, in the alternative, to order payment of his

disturbance compensation as bona fide tenant in an amount not less than P15,000.00 per hectare.

4. [CFI of Bulacan] December 8, 1978 Order: respondent Judge Roque A. Tamayo denied the

petitioners' supplemental motion, holding that to admit petitioners' complaint in intervention would be

tantamount to allowing a person to sue the State without its consent since the claim for disturbance

compensation is a claim against the State.

4.a. [CFI of Bulacan] Petitioners filed a motion for reconsideration but this was denied by

respondent judge.

4.a.1. [SC] Thus, the petitioners filed an instant petition, which was denied for lack of

merit.

4.a.2. [SC] Petitioners filed a motion for reconsideration, limiting the discussion on the

issue of lack of jurisdiction of the trial court over the expropriation case.

4.a.3. [SC] The Court granted the motion for reconsideration and gave due course

to the petition.

4.b. [CFI of Bulacan] December 22, 1978: The OSG (appealing from the portion of the December

8, 1978 decision of the CFI which fixed the compensation for the land expropriated at P30.00 per

square meter) filed in behalf of the Republic of the Philippines a notice of appeal and a first

motion for extension of 30 days from January 12, 1979 within which to file record on appeal

which was granted by respondent court.

4.b.1. [CFI of Bulacan] Counsel for private respondents filed an objection to the public

respondent's record on appeal claiming that the same was filed beyond the

reglementary period. The CFI dismissed the appeal interposed by the Republic.

4.b.2. [CFI of Bulacan] The OSG moved for reconsideration but this was denied for lack

of merit.

4.b.3. [CA] The public respondent filed a petition for certiorari, prohibition and

mandamus with preliminary injunction seeking the annulment of the CFI orders. The CA

dismissed public respondent's petition.

4.b.4. [SC] The public respondent filed a petition asking this Court to annul the CA

decision and to direct and compel the lower court to approve the Government's

record on appeal and to elevate the same to the CA. In a decision dated August 10,

1981, the Court granted the petition and directed the trial court to approve the

Government's record on appeal and to elevate the same to the CA.

Issue/s:

[TOPIC ISSUE] Whether or not the petitioners had the right to intervene in the expropriation proceedings

instituted by the State against the Aldabas (private respondents) as registered owners of the subject

property. (NO)

Held / Ratio:

- Dispositive: Petition is denied for lack of merit.

- Intervention is not a matter of right but may be permitted by the courts when the applicant shows facts

which satisfy the requirements of the law authorizing intervention. Under Section 2, Rule 12 of the Revised

Rules of Court, what qualifies a person to intervene is his possession of a legal interest in the matter in

litigation, or in the success of either of the parties, or an interest against both, or when he is so situated as

to be adversely affected by a distribution or other disposition of property in the custody of the court or an

officer thereof. Such interest must be actual, direct and material, and not simply contingent and expectant.

- Petitioners claim that Celso Pagtalunan possesses legal interest in the matter in litigation for he, not

private respondents, is the party entitled to just compensation for the subject property sought to be

expropriated or, in the alternative, disturbance compensation as a bona fide tenant. Petitioners base their

claim for just compensation on the certificate of land transfer issued to them, where the tenant

farmer/grantee is deemed owner of the agricultural land identified therein. Petitioners contend that the

certificate is evidence of their legal ownership of a portion of the subject property. Thus, they conclude that

they are entitled to a portion of the proceeds from the expropriation proceedings instituted over the

subject property.

- The Court is fully aware that the phrase "deemed to be the owner" is used to describe the grantee of a

certificate of land transfer. But the import of such phrase must be construed within the policy framework of

Pres. Decree No. 27, and interpreted with the other stipulations of the certificate issued pursuant to this

decree. Pres. Decree No. 27 (Tenant Emancipation Decree) recognized the necessity to encourage a

more productive agricultural base of the country's economy. To achieve this end, the decree laid down a

system for the purchase by small farmers, long recognized as the backbone of the economy, of the lands

they were tilling. A careful study of the provisions of Pres. Decree No. 27, and the certificate of land

transfer issued to qualified farmers, will reveal that the transfer of ownership over these lands is subject to

particular terms and conditions the compliance with which is necessary in order that the grantees can

claim the right of absolute ownership over them.

> And under Pres. Decree No. 266 which specifies the procedure for the registration of title to lands

acquired, full compliance by the grantee is required for a grant of title under the Tenant

Emancipation Decree and the subsequent issuance of an emancipation patent in favor of the

farmer/grantee [Section 2, Pres. Decree No. 226]. It is the emancipation patent which constitutes

conclusive authority for the issuance of an Original Certificate of Transfer, or a Transfer Certificate of

Title, in the name of the grantee.

Hence, the mere issuance of the certificate of land transfer does not vest in the farmer/grantee

ownership of the land described therein. The certificate simply evidences the government's

recognition of the grantee as the party qualified to avail of the statutory mechanisms for the

acquisition of ownership of the land tilled by him as provided under Pres. Decree No. 27. Neither is

this recognition permanent nor irrevocable. Failure on the part of the farmer/grantee to comply with

his obligation to pay his lease rentals or amortization payments when they fall due for a period of

two (2) years to the landowner or agricultural lessor is a ground for forfeiture of his certificate of

land transfer [Section 2, Pres. Decree No. 816].

> It is only after compliance with the above conditions which entitle a farmer/grantee to an

emancipation patent that he acquires the vested right of absolute ownership in the landholding (a

right which has become fixed and established, and is no longer open to doubt or controversy). At

best, the farmer/grantee, prior to compliance with these conditions, merely possesses a contingent

or expectant right of ownership over the landholding.

- Petitioners have not been issued an emancipation patent. Furthermore, they do not dispute private

respondents' allegation that they have not complied with the conditions enumerated in their certificate of

land transfer which would entitle them to a patent. Petitioners do not even claim that they had remitted to

private respondents, through the Land Bank of the Philippines, even a single amortization payment for the

purchase of the subject property.

> Under these circumstances, petitioners cannot now successfully argue that Celso Pagtalunan is

legally entitled to a portion of the proceeds from the expropriation proceedings corresponding to

the value of the landholding. Therefore, considering that petitioners are not entitled to just

compensation for the expropriation of the subject property, nor to disturbance compensation under

Rep. Act No. 3844, as amended, the Court finds that the trial court committed no reversible error in

denying petitioners' motion for leave to intervene in the expropriation proceedings.

DIGESTED BY: SHELAN TEH

Вам также может понравиться

- Secretary of Agrarian Reform vs. Tropical Homes, Inc., - DigestДокумент3 страницыSecretary of Agrarian Reform vs. Tropical Homes, Inc., - DigestsherwinОценок пока нет

- Vinzons-Magana Vs EstrellaДокумент1 страницаVinzons-Magana Vs EstrellaAthena Santos0% (1)

- 24 Province of Tayabas Vs Perez 66 Phil 467Документ3 страницы24 Province of Tayabas Vs Perez 66 Phil 467LalaLaniba100% (1)

- Sanchez V MarinДокумент1 страницаSanchez V MarinEsp BsbОценок пока нет

- Agra Case Digest FersalДокумент16 страницAgra Case Digest FersalFersal AlbercaОценок пока нет

- Republic V Mangotara-DigestДокумент4 страницыRepublic V Mangotara-DigestG OrtizoОценок пока нет

- 5) Macalalag Vs OmbudsmanДокумент2 страницы5) Macalalag Vs OmbudsmanAngeline De GuzmanОценок пока нет

- Zurbano v. EstrellaДокумент1 страницаZurbano v. EstrelladavebarceОценок пока нет

- #2 Cachero Vs Marzan 1991Документ2 страницы#2 Cachero Vs Marzan 1991CentSering100% (1)

- (Property) 44 Vencilao V VanoДокумент4 страницы(Property) 44 Vencilao V VanoChino VОценок пока нет

- CASE DIGEST: Villaviza Vs PanganibanДокумент1 страницаCASE DIGEST: Villaviza Vs PanganibanMaria Anna M Legaspi100% (2)

- Omandam v. CAДокумент1 страницаOmandam v. CACesyl Patricia BallesterosОценок пока нет

- SterlingДокумент2 страницыSterlingBrian YuiОценок пока нет

- Ualat V Judge Ramos and Del Callar V SalvadorДокумент2 страницыUalat V Judge Ramos and Del Callar V SalvadorPj DegolladoОценок пока нет

- NEGRETE vs. COURT OF FIRST INSTANCE OF MARINDUQUEДокумент1 страницаNEGRETE vs. COURT OF FIRST INSTANCE OF MARINDUQUELeo TumaganОценок пока нет

- Heirs of Cayetano Pangan vs. Spouses RogelioДокумент2 страницыHeirs of Cayetano Pangan vs. Spouses RogelioHoney Crisril CalimotОценок пока нет

- Dy Vs CAДокумент2 страницыDy Vs CASarah Victorio100% (1)

- Agrarian Law (Basbas vs. Entena)Документ3 страницыAgrarian Law (Basbas vs. Entena)Maestro LazaroОценок пока нет

- Colorado v. AgapitoДокумент12 страницColorado v. AgapitoCla BAОценок пока нет

- 20 Director of Land V MERALCOДокумент3 страницы20 Director of Land V MERALCOFlorieanne May ReyesОценок пока нет

- Panganiban Vs Dayrit DigestДокумент9 страницPanganiban Vs Dayrit DigestaiceljoyОценок пока нет

- Tavera Vs El HogarДокумент3 страницыTavera Vs El HogarLizzette Dela PenaОценок пока нет

- 1B Bienvenido Dino V Pablo OlivarezДокумент2 страницы1B Bienvenido Dino V Pablo OlivarezEi Ar Taradji100% (1)

- Petron Corporation V CIRДокумент2 страницыPetron Corporation V CIRiciamadarangОценок пока нет

- Miller vs. Director of LandsДокумент2 страницыMiller vs. Director of LandsTrem GallenteОценок пока нет

- Orchard Realty and Development Corporation vs. RepublicДокумент2 страницыOrchard Realty and Development Corporation vs. RepublicMay RMОценок пока нет

- Cabral vs. Court of Appeals DigestДокумент1 страницаCabral vs. Court of Appeals DigestJosie0% (1)

- Engracia Vinzons vs. EstrellaДокумент2 страницыEngracia Vinzons vs. EstrellavanityОценок пока нет

- Eristingcol Vs Court of AppealsДокумент3 страницыEristingcol Vs Court of AppealsJf ManejaОценок пока нет

- 1 Endaya Vs CAДокумент3 страницы1 Endaya Vs CAAngelica GarcesОценок пока нет

- 12 LBP V Dalauta PDFДокумент4 страницы12 LBP V Dalauta PDFTon Ton CananeaОценок пока нет

- 6 Digest Julio Tapec Vs CA RaguiragДокумент2 страницы6 Digest Julio Tapec Vs CA RaguiragLee100% (3)

- Abeto Vs GarcesaДокумент2 страницыAbeto Vs GarcesaErwin DacanayОценок пока нет

- Director of Lands V AgustinДокумент1 страницаDirector of Lands V AgustinGel TolentinoОценок пока нет

- Case Digest: Republic (Mindanao Med) v. CAДокумент1 страницаCase Digest: Republic (Mindanao Med) v. CAMaria Anna M LegaspiОценок пока нет

- Teodoro Vs MacaraegДокумент2 страницыTeodoro Vs MacaraegcrisОценок пока нет

- Ramos vs. ManalacДокумент5 страницRamos vs. ManalacAdrianne BenignoОценок пока нет

- REQUISIT and Essential Elements Tenancy and Lease of The PHILДокумент29 страницREQUISIT and Essential Elements Tenancy and Lease of The PHILirene anibongОценок пока нет

- Land TitlesДокумент5 страницLand Titleswilfred100% (1)

- Heirs of Claudel V CA DigestДокумент3 страницыHeirs of Claudel V CA Digestnicole hinanay100% (3)

- Cacho v. CAДокумент2 страницыCacho v. CAReymart-Vin MagulianoОценок пока нет

- 32 - Raza Appliance Center Vs VillarazaДокумент2 страницы32 - Raza Appliance Center Vs VillarazaRia GabsОценок пока нет

- Republic V AgunoyДокумент2 страницыRepublic V AgunoyBarrrMaidenОценок пока нет

- Francisco V Rojas DigestДокумент3 страницыFrancisco V Rojas DigestMickey Ortega75% (4)

- Meralco Securities Industrial Corp V CBAAДокумент1 страницаMeralco Securities Industrial Corp V CBAAJohn YeungОценок пока нет

- Case DigestsДокумент24 страницыCase DigestsMa Nikka Flores OquiasОценок пока нет

- 68 Frias V SorongonhaaДокумент1 страница68 Frias V SorongonhaaChristine Ang CaminadeОценок пока нет

- Pastor v. CA, G.R. No. L-56340, June 24, 1983 (122 SCRA 85)Документ10 страницPastor v. CA, G.R. No. L-56340, June 24, 1983 (122 SCRA 85)ryanmeinОценок пока нет

- Ermac vs. MedeloДокумент1 страницаErmac vs. MedeloJessa F. Austria-CalderonОценок пока нет

- Yuk Ling Ong vs. Co, 752 SCRA 42, February 25, 2015Документ12 страницYuk Ling Ong vs. Co, 752 SCRA 42, February 25, 2015TNVTRL100% (1)

- G.R. No. 175380 PDFДокумент5 страницG.R. No. 175380 PDFkyla_0111Оценок пока нет

- Boston Bank of The Philippines, (Formerly Bank of Commerce), vs.Документ4 страницыBoston Bank of The Philippines, (Formerly Bank of Commerce), vs.michaellaОценок пока нет

- 13 Dar VS DecsДокумент3 страницы13 Dar VS DecsAnthony ValerosoОценок пока нет

- 15 Mijares V RanadaДокумент1 страница15 Mijares V RanadaMark Bryant VitorОценок пока нет

- GR No. 107967 Case DigestДокумент2 страницыGR No. 107967 Case DigestRaym TrabajoОценок пока нет

- Republic V Sin Case DigestДокумент2 страницыRepublic V Sin Case DigestCherry May Sanchez100% (2)

- Salitico vs. Heirs of FelixДокумент3 страницыSalitico vs. Heirs of FelixAnaОценок пока нет

- SANSIO PHILIPPINES, INC. vs. SPOUSES ALICIA AND LEODEGARIO MOGOL, JR.Документ2 страницыSANSIO PHILIPPINES, INC. vs. SPOUSES ALICIA AND LEODEGARIO MOGOL, JR.Jei Essa AlmiasОценок пока нет

- Petitioners vs. VS.: Third DivisionДокумент7 страницPetitioners vs. VS.: Third Divisionthirdy demaisipОценок пока нет

- Agrarian Law - CARP Tenancy Set 2Документ27 страницAgrarian Law - CARP Tenancy Set 2Liz ZieОценок пока нет

- Cases - SourcesДокумент15 страницCases - SourcesAiken Alagban LadinesОценок пока нет

- Waiver of Rights - SampleДокумент1 страницаWaiver of Rights - SampleAiken Alagban LadinesОценок пока нет

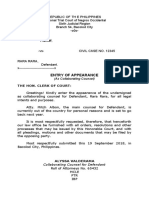

- Entry of Appearance: (As Collaborating Counsel)Документ2 страницыEntry of Appearance: (As Collaborating Counsel)Aiken Alagban LadinesОценок пока нет

- SPA SampleДокумент2 страницыSPA SampleAiken Alagban LadinesОценок пока нет

- Christmas CardsДокумент1 страницаChristmas CardsAiken Alagban LadinesОценок пока нет

- ST Kiss The Miss Goodbye 8x10 1Документ1 страницаST Kiss The Miss Goodbye 8x10 1Aiken Alagban LadinesОценок пока нет

- Affidavit of LossДокумент1 страницаAffidavit of LossAiken Alagban LadinesОценок пока нет

- Materials UsedДокумент3 страницыMaterials UsedAiken Alagban LadinesОценок пока нет

- Judicial Affidavit - SampleДокумент7 страницJudicial Affidavit - SampleAiken Alagban LadinesОценок пока нет

- ClubsДокумент1 страницаClubsAiken Alagban LadinesОценок пока нет

- Joint Affidavit of Discrepancy SampleДокумент1 страницаJoint Affidavit of Discrepancy SampleAiken Alagban Ladines100% (5)

- Colds/Flu Prevention Through VaccinationДокумент1 страницаColds/Flu Prevention Through VaccinationAiken Alagban LadinesОценок пока нет

- Abstract of Tomato PlantationДокумент1 страницаAbstract of Tomato PlantationAiken Alagban LadinesОценок пока нет

- Effective Communication As A Means To Global PeacДокумент2 страницыEffective Communication As A Means To Global PeacAiken Alagban Ladines100% (1)

- LTFRB Revised Rules of Practice and ProcedureДокумент25 страницLTFRB Revised Rules of Practice and ProcedureSJ San Juan100% (2)

- Affidavit of LossДокумент1 страницаAffidavit of LossAiken Alagban LadinesОценок пока нет

- Joint Affidavit of Two Disinterested PersonsДокумент1 страницаJoint Affidavit of Two Disinterested PersonsAiken Alagban LadinesОценок пока нет

- VaccinationДокумент1 страницаVaccinationAiken Alagban LadinesОценок пока нет

- Celebrating His Love - EditedДокумент1 страницаCelebrating His Love - EditedAiken Alagban LadinesОценок пока нет

- Compassion in Action - EditedДокумент1 страницаCompassion in Action - EditedAiken Alagban LadinesОценок пока нет

- Bar SchedДокумент1 страницаBar SchedAiken Alagban LadinesОценок пока нет

- Galatians 5 Living by The Spirit's PowerДокумент1 страницаGalatians 5 Living by The Spirit's PowerAiken Alagban LadinesОценок пока нет

- Daily RemindersДокумент4 страницыDaily RemindersAiken Alagban LadinesОценок пока нет

- Registered VotersДокумент1 страницаRegistered VotersAiken Alagban LadinesОценок пока нет

- Answer - Reswri 2Документ6 страницAnswer - Reswri 2Aiken Alagban LadinesОценок пока нет

- Revised Rules On Administrative Cases in The Civil ServiceДокумент43 страницыRevised Rules On Administrative Cases in The Civil ServiceMerlie Moga100% (29)

- PassportДокумент2 страницыPassportAiken Alagban LadinesОценок пока нет

- Tax NotesДокумент6 страницTax NotesAiken Alagban LadinesОценок пока нет

- Resolution To Open Bank AccountsДокумент1 страницаResolution To Open Bank AccountsAiken Alagban LadinesОценок пока нет

- Code of Professional ResponsibilityДокумент3 страницыCode of Professional ResponsibilityAiken Alagban LadinesОценок пока нет

- People v. Gatward - CaseДокумент10 страницPeople v. Gatward - CaseRobeh AtudОценок пока нет

- Horace Butler v. James Aiken, Warden, Central Correctional Institute, Travis Medlock, Attorney General, State of South Carolina, 864 F.2d 24, 4th Cir. (1988)Документ6 страницHorace Butler v. James Aiken, Warden, Central Correctional Institute, Travis Medlock, Attorney General, State of South Carolina, 864 F.2d 24, 4th Cir. (1988)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Ho Vs PeopleДокумент3 страницыHo Vs Peoplemaricar bernardinoОценок пока нет

- 02-IRRI v. NLRC G.R. No. 97239 May 12, 1993 PDFДокумент5 страниц02-IRRI v. NLRC G.R. No. 97239 May 12, 1993 PDFJopan SJОценок пока нет

- Basilio de Vera, Luis de Vera, Felipe de Vera, Heirs of Eustaquia de Vera-Papa Represented byДокумент2 страницыBasilio de Vera, Luis de Vera, Felipe de Vera, Heirs of Eustaquia de Vera-Papa Represented bymichaellaОценок пока нет

- United States v. Canetha Johnson, 11th Cir. (2015)Документ19 страницUnited States v. Canetha Johnson, 11th Cir. (2015)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Hillaire, 1st Cir. (2017)Документ6 страницUnited States v. Hillaire, 1st Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Intro To Law-Legaspi V Min of Fin & Nepa V OngpinДокумент7 страницIntro To Law-Legaspi V Min of Fin & Nepa V OngpinKim MedranoОценок пока нет

- The Rizal Bill of 1956Документ16 страницThe Rizal Bill of 1956Natasha Mae DimaraОценок пока нет

- Brown Cert ReplyДокумент17 страницBrown Cert ReplyBen WinslowОценок пока нет

- 2018-08-1 - Insulin Litigation - DE 17-699 Final Order - Julia Boss PapersДокумент20 страниц2018-08-1 - Insulin Litigation - DE 17-699 Final Order - Julia Boss PapersThe Type 1 Diabetes Defense FoundationОценок пока нет

- Bognot vs. RRI LendingДокумент2 страницыBognot vs. RRI LendingCeline GarciaОценок пока нет

- Ii. Effect and Application of Laws C. Retroactivity of LawsДокумент6 страницIi. Effect and Application of Laws C. Retroactivity of LawsNath AntonioОценок пока нет

- Claim of Right For AmericansДокумент16 страницClaim of Right For Americansextemporaneous100% (3)

- Case Digests Political Law: Francisco vs. House of Representatives (415 SCRA 44 G.R. No. 160261 10 Nov 2003)Документ5 страницCase Digests Political Law: Francisco vs. House of Representatives (415 SCRA 44 G.R. No. 160261 10 Nov 2003)Katrina Anne Layson YeenОценок пока нет

- Hardwick v. HeywardДокумент33 страницыHardwick v. HeywardlegalclipsОценок пока нет

- (Deemed University) : The Indian Law InstituteДокумент10 страниц(Deemed University) : The Indian Law InstituteGILLHARVINDERОценок пока нет

- Exemptions of Article 3 of The Civil Code of The PhilippinesДокумент2 страницыExemptions of Article 3 of The Civil Code of The PhilippinesMona LizaОценок пока нет

- Chiok Vs PeopleДокумент15 страницChiok Vs PeopleJaycil GaaОценок пока нет

- Intro Bill of Rights (Loanzon)Документ29 страницIntro Bill of Rights (Loanzon)JosemariaОценок пока нет

- Judge's Ruling On Damages Awarded in Dawe v. CUSA, CCPOAДокумент11 страницJudge's Ruling On Damages Awarded in Dawe v. CUSA, CCPOAjon_ortizОценок пока нет

- Insurance Law BasicsДокумент4 страницыInsurance Law BasicsParamesh ChakrabortyОценок пока нет

- AUSL Curriculum and LEB MO 5, Series of 2016Документ1 страницаAUSL Curriculum and LEB MO 5, Series of 2016EK ANGОценок пока нет

- Right To Travel by Jack McLambДокумент4 страницыRight To Travel by Jack McLambVen Geancia100% (2)

- 1.1 Definition of Constitutional Law: of Constitutiona Aw Act, 86 C, 982 A - A SДокумент25 страниц1.1 Definition of Constitutional Law: of Constitutiona Aw Act, 86 C, 982 A - A SVin UmОценок пока нет

- Perkins v. Benguet Consol. Mining Co. 342 U.S. 437, 72 S. Ct. 413 (1952)Документ9 страницPerkins v. Benguet Consol. Mining Co. 342 U.S. 437, 72 S. Ct. 413 (1952)nicole coОценок пока нет

- Santos vs. ComelecДокумент2 страницыSantos vs. ComelecMichael C. PayumoОценок пока нет

- Stealth Bastard Deluxe End User Licence AgreementДокумент5 страницStealth Bastard Deluxe End User Licence AgreementCarlosEscobarZarzarОценок пока нет

- Seludo CaseДокумент42 страницыSeludo CaseAj SobrevegaОценок пока нет