Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Quitmeyer Digital Naturalism Doctoral Consortium

Загружено:

Andrew QuitmeyerАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Quitmeyer Digital Naturalism Doctoral Consortium

Загружено:

Andrew QuitmeyerАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Digital Naturalism: Interspecies

Performative Tool Making for

Embodied Science

Andrew Quitmeyer

Abstract

Digital Media PhD Student

Digital Naturalism investigates the role that digital

media can play in field Ethology. While digital

technology plays an increasingly larger role in the

Ethologists process, its use tends to be limited to the

experimentation and analysis stages. My goal is to work

with scientists to develop context-dependent,

behavioral tools promoting novel interactions between

animal, man, and environment. The aim is to empower

the early exploratory phases of their research as well as

the later representation of their work. I will test a

methodology combining analytical tool making and

interaction studies with modern ethology.

Georgia Institute of Technology

85 Fifth Street

Atlanta, GA 30308 USA

andy@quitmeyer.org

Author Keywords

Physical Computing; Performance; Critical Making;

UbiComp; Ethology; Interspecies Interaction

Permission to make digital or hard copies of part or all of this work for

personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are

not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that

copies bear this notice and the full citation on the first page. Copyrights

for third-party components of this work must be honored. For all other

uses, contact the Owner/Author.

Copyright is held by the owner/author(s).

UbiComp '13, Sep 08-12 2013, Zurich, Switzerland

ACM 978-1-4503-2215-7/13/09.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2494091.2501084

ACM Classification Keywords

H.5.m. Information interfaces and presentation (e.g.,

HCI): Miscellaneous.

Research Summary

Introduction

My research seeks to investigate the role of digital

media in field Ethology. Under the concept of Digital

Naturalism, I explore interaction and communication

between human and non-human agents through a

behavioral media. The concept will examine the

development of situated digital tools and performances

to discover, analyze, and share behavioral information

from the natural world. This necessitates design not

only for experimentation and engagement, but also for

reflection upon the (typically human-exclusive) values

and assumptions embedded in the off-the-shelf and

bespoke technologies utilized in the research. This

research expects to contribute valuable insights to

ubiquitous computing design for cross-species

interaction.

Digital Naturalism

Digital Naturalism works to developing methods for a

more holistic use of technology in Ethology. The two

main problems in current digital ethological it seeks to

address are 1) the lack of open-ended digital tools for

exploration and dissemination and 2) technological

determinism impacting their scientific process.

Through my prior experiences developing tools for

ethologists, I have had the opportunity to research, via

interviews and involved collaborative practice, how the

ethological process typically intersects with technology

[1]. Though greatly simplified, this general outline

displays how most digital involvement in ethological

work takes place in the form of tools to capture or

expedite the analysis of data.

Complementing the purely number-crunching abilities

of digital tools, I wish to develop uses of digital media

which can span the entire scientific process. In his

manuscript, Ethology, Chauvin describes a key practice

of modern Ethologists: As in antiquity, these

naturalists observed animals in nature, but they were

armed with all the insights of modern scientific

thought [2]. I want to further arm these scientists with

the unique, new abilities for perception and insight

afforded through digital media.

My proposed framework emphasizes involving digital

technology on both ends of the scientific process, as

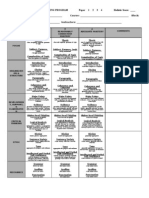

Figure 1 - Chart derived from interviews with Ethological Scientists depicting the typical intersection of their workflow with Digital

Technology ("Digital Tools") and the proposed Digital Media approach which seeks to complement the entire workflow, particularly the

beginning and endpoints to their process which are typically not as involved with technology.

these are the areas where little digital intervention

typically occurs. Thus, I will focus on A) the early

stages of science, particularly the experiential assay

portion, where ethologists get-to-know their target

specimens through rapid exploratory mini-experiments,

as well as B) the later stages where scientists seek to

disseminate their behavioral findings either to the

public or even just to their peers. In addressing these

fields, Digital Naturalisms methodology is synthesized

from existing research in Critical Making and

Interaction Studies.

Figure 2 Ducks Feed People exploratory

situated performance project between

digital, animal, and human agents.

Figure 3 Field testing the simple

robotic woodpecker with responses

from tree-dwelling ants.

Critical Making

Critical Making is the concept of learning through the

creation and use of ones own tools [3]. This crafting

and material experimentation brings forth unforeseen

tacit and experiential knowledge concerning the tools

environment, abilities, and interactions. Context-driven

tool-making has been a significant feature in ethology

from Tinbergens pine-cone experiments with

Philanthus wasps [4], to using army-ants as

Aphaenogaster colony extraction devices [5]. In fact,

the Naturalism concept of my framework derives from

ethologys foundations in 19th and early 20th century

natural history which promoted the value of situated

experimentation within the natural world [6]. Scientists

like Tinbergen lend credence to the seemingly romantic

notions of the wandering naturalist:

I believe strongly in the importance of natural or

unplanned experiments. In the planned experiment all

one does is to keep a few more possible variables

constant; but it is amazing how far one can get by

critically selecting the circumstances of one's natural

experiment Also an extremely valuable store of

factual knowledge is picked up by a young naturalist

during his seemingly aimless wanderings in the

fields.[4]

One of the key concerns that several of my ethological

interviewees expressed was about the influence of

technological determinism in their experimentation [1].

This is when ones training with certain pieces of

technology leads to experimentation designed around

the use of this device, as opposed to crafting an

experiment around a key behavioral question. A Critical

Making approach avoids this influence where scientists

design and question the experiment and technology in

parallel.

During my fieldwork last summer at the Smithsonian

Tropical Research Institute (STRI), I managed to test a

complete application of this approach. I studied and

worked with a previous STRI fellow studying Azteca ant

aggression. Noting the key concerns in his early

research, I developed a simple robotic woodpecker

mini-robot, which we were able to iteratively test and

develop into a robust tool leading to new pathways in

his official research [8]. My robotic woodpecker,

designed and implemented on location, allowed him to

continue pursuing this early, free-form stage of

research, while still collecting valuable empirical data,

since now the aggressive probe could actually be

calibrated.

By critically designing our own ethological tools, we will

be able to harness the unique abilities of digital

technology while maintaining adaptability and

organismal specificity with the tools. Building a tool

suited to particular context works to highlight particular

features of its connections with the target organism and

local environment. This will lead to more robust

experimentation focused precisely on the ethologists

true research questions.

Interaction Studies

The ethologist holds a responsibility to communicate

the intricacies of behaviors. Effectively describing the

complexity of these processes, however, is a difficult

task. Typically scientists communicate to the

community at large through the traditional means of

research papers or even talks. Occasionally videos or

animations can also be used to further elucidate what

they have found, but further technologically aided

communication tends to be rare. In many cases, an

ethologist will often find it easier to bring ones peer

directly into the field to most aptly describe the

particular behavioral phenomenon. Media scholar, Ian

Bogost, attributes these sorts of communication

difficulties to the fact that effective behavioral

representation requires inscription in a medium which

can actually enact behaviors [7]. With Chauvin, Bogost

praises the use of process-based, computational media,

for exactly this use [2][7].

To communicate space, architects create real-world

models, to demonstrate temporal reactions, physicists

shoot demonstration videos, and this is why computer

simulations, recreating behaviors through actual

processes, have been so useful to ethologists in recent

years. Simulations however can be distancing, or even

misleading, to the untrained eye, and limit the tacit

knowledge obtained through real-life interactions with

creatures. This is why I wish to expand the use of

computers abilities and investigate the ethologists use

of interactive presentations.

Concrete examples come from my research with DWIG

Lab, where I research hybrid physical/digital

performance projects to prompt novel behaviors and

understandings. In one simple project, Ducks Feed

People [8], the movement of ducks in one area of a

public park triggers the release of candy from a robotic

duck head in the human area of the park. This crossspecies performance inverts the traditional relationships

between humans and ducks, inviting inspection of

ducks underlying motivations and behaviors. These

non-expert humans quickly discover unnoticed

attributes about their environment and the ducks

behavior, such as what frightens them or draws them

near, through their engagement with this hybrid

artifact.

Thus, like film's early cinmatographe, a device that

could both record and project video, performative tools

specific to a context empower not only the collection

and analysis of behavioral data, but also its

presentation and dissemination. Thus the interactive

artifacts, resulting from the scientists prior digital

crafting, can procedurally communicate the embedded

behavioral rhetoric to third parties.

Methodology

A core component of Digital Naturalism will be the

creation and evaluation of digital design methodologies

for naturalistic animal interaction. While still in

development, this framework will blend approaches

from the aforementioned fields for an overall reflexive

practice in applied design.

Digital Naturalism necessarily entails building and

utilizing performative tools within the target organisms

natural context. This requires research alongside

ethologists working in the field. I am actively connected

to several scientific communities as a technological

consultant, particularly with many colleagues at STRI.

Together I will work with them to craft exploratory

tools, implement these tools in their field research, and

design expressive presentations incorporating their

tools to communicate their scientific findings. These

works, co-created between the scientists, myself, the

environment, and the biological subjects, will offer a

means sharing research qualitatively and

quantitatively. Thereafter, I will evaluate the

methodology pursued and construct a framework for

future designs of digital-biotic scientific-artistic

systems.

Research Plan

Currently I am in the Panamanian Rainforest carrying

out summer field research in the middle of my Ph.D.s

overall research plan.

Figure 4 Ethologist created circuit for

behavioral probing and cultural

performance. This custom-built

mainboard takes input from the

scientist for partial control over a

firefly costume emulating Pyrophorus

noctilucus (phosphorescent clickbeetles).

I spent the first year of my Ph.D. procuring a

background on the current state of digital technology

involving animal behavior. Of particular focus, were

cybiotic systems where information feedback between

both the digital and biological agents. During the 2012

field season, I traveled for the first time, to what has

now become my primary field site at the Smithsonian

Tropical Research Institute in Gamboa, Panama.

During the second year, I developed the concept of

Digital Naturalism as I performed more research into

situated interaction, crafting, and ethology. Now,

during the current field season, I am testing out a

prototypical incarnation of this synthesized theory. I am

running two parallel research timelines while in Panama

with STRI, one broad and one deep. With the broad

approach, I conduct IRB approved ethnographic

surveys, critical making workshops, and interactive

performances with the community as a whole. One

current project, Living Lightning, teaches physical

computing basics while building digital firefly costumes

to interact with the animals during a pedagogical

performance emulating their mating rituals of

Pyrophorus noctilucus.

In the deep timeline, I am intimately working with

two core collaborators on ant and bat behavior, and

having them perform custom design exercises. We are

working towards the construction of more intricate

Performative tools that will permit open-ended

exploration with their research subjects. These

collaborators are being shadowed, interviewed, and

lead through performance exercises as well as

contributing first-hand documentation to the research

website, www.digitalnaturalism.org. At the end of this

season they will each create interactive performances

to present to the public community along with their

creatures and tools.

In my third academic year, I will be teaching a custom

version of the class Principles of Interaction Design

with an emphasis on ubiquitous computing for animal

interaction. I will also be synthesizing my findings over

this year from the current field season, and prepare for

the final 2014 summer field season. During this primary

session, I will more thoroughly evaluate the more fully

realized frameworks, before I prepare my final

dissertation in Fall 2014/Spring 2015.

Biographical Sketch Andrew Quitmeyer

References

PhD Program

Digital Media Ph.D. at Georgia Tech

Began: August 2011

Passed all Qualifying exams: May 2013

Expected completion: May 2015

[1]

A. Quitmeyer, Personal Interviews with

Ethological Researchers at ASU and STRI.

2013.

[2]

R. Chauvin, Ethology: the biological study of

animal behavior. International Universities

Press, 1977, p. 245.

[3]

M. Ratto, Critical Making: Conceptual and

Material Studies in Technology and Social Life,

The Information Society, vol. 27, no. 4, pp.

252260, Jul. 2011.

[4]

Niko Tinbergen, Curious naturalists. Univ of

Massachusetts Press, 1974, p. 268.

[5]

A. A. Smith and K. L. Haight, Army Ants as

Research and Collection Tools, 2008. [Online].

Available: http://www.insectscience.org/8.71/.

[6]

K. Lorenz, King Solomons Ring: New Light on

Animal Ways. Psychology Press, 1952, p. 224.

[7]

I. Bogost, Persuasive Games: The Expressive

Power of Videogames. MIT Press, 2007, p. 450.

[8]

Ducks Feed People! [Online]. Available:

http://dwig.lmc.gatech.edu/projects/ducks/.

[9]

C. DiSalvo, Adversarial Design, vol. 0. Mit Press,

2012, p. 145.

Advisors

The research is primarily advised by Dr. Michael Nitsche

at Georgia Tech who works tirelessly with me on this

research to find ways to synthesize the manifold

approaches from the worlds of performance,

architecture, design, and HCI. The work is also

gratefully co-advised by several committee members

from various fields: Carl DiSalvo (Design Georgia

Tech), Stephen Pratt (Behavioral Ecology - ASU),

William Wcislo (Behavioral Ecology Smithsonian), and

Ian Bogost (Media and Philosophy Georgia Tech).

Collaborators

My research would also not function without the

participation of numerous animal scientists at the

Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. In particular,

Peter Marting, and Antonia Hubancheva, function as my

first official scientific collaborators combining critical

making and performance with their research.

Acknowledgements

My research is primarily self-funded through design and

achievement awards, such as the Instructables Grand

Prize Design Challenge, and Georgia Techs Ivan Allen

Legacy Award.

Вам также может понравиться

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Triggers of Mind ControlДокумент47 страницTriggers of Mind ControlUtkarsh Gupta100% (1)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5795)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Power of The Orton Gillingham ApproachДокумент15 страницThe Power of The Orton Gillingham ApproachGabriela Seara100% (1)

- 4methods and Strategies in Teaching The ArtsДокумент13 страниц4methods and Strategies in Teaching The ArtsFrances Gallano Guzman Aplan50% (2)

- Design Fiction: Frontiers of Ecological Interaction (Fall 2017)Документ52 страницыDesign Fiction: Frontiers of Ecological Interaction (Fall 2017)Andrew Quitmeyer100% (1)

- Making Inference and GeneralizationДокумент4 страницыMaking Inference and GeneralizationZyndee de Guzman100% (1)

- Robert Fisher PSVДокумент18 страницRobert Fisher PSVJiannifen Luwee100% (1)

- Knowing OneselfДокумент15 страницKnowing OneselfArcadian Eunoia100% (1)

- CHAPTER 10 CreatingДокумент14 страницCHAPTER 10 CreatingJan Lagbo Goliman67% (3)

- Becker - Everyman His Own Historian PDFДокумент17 страницBecker - Everyman His Own Historian PDFDarek SikorskiОценок пока нет

- Daily Lesson Log APPLIED SUBJECT - GAS - Discipline and Ideas in The Social ScienceДокумент4 страницыDaily Lesson Log APPLIED SUBJECT - GAS - Discipline and Ideas in The Social ScienceHannae pascua100% (1)

- PhenomenologyДокумент27 страницPhenomenologyMerasol Matias Pedrosa100% (1)

- Cambridge English Starters TESTДокумент5 страницCambridge English Starters TESTmiren48Оценок пока нет

- Yarncraft and Cognition - Creativity and Cognition 2017Документ2 страницыYarncraft and Cognition - Creativity and Cognition 2017Andrew QuitmeyerОценок пока нет

- Tiger Digital Enrichment System ManualДокумент34 страницыTiger Digital Enrichment System ManualAndrew QuitmeyerОценок пока нет

- Hiking Hacks: Workshop Model For Exploring Wilderness Interaction Design (Preprint) - Andrew QuitmeyerДокумент12 страницHiking Hacks: Workshop Model For Exploring Wilderness Interaction Design (Preprint) - Andrew QuitmeyerAndrew QuitmeyerОценок пока нет

- Red Panda Digital Enrichment System ManualДокумент22 страницыRed Panda Digital Enrichment System ManualAndrew QuitmeyerОценок пока нет

- Orangutan Digital Enrichment System ManualДокумент24 страницыOrangutan Digital Enrichment System ManualAndrew QuitmeyerОценок пока нет

- See Yourself E (X) Ist Catalog - Madeline SchwartzmanДокумент13 страницSee Yourself E (X) Ist Catalog - Madeline SchwartzmanAndrew Quitmeyer50% (2)

- Digital Naturalism - Theory and GuidelinesДокумент21 страницаDigital Naturalism - Theory and GuidelinesAndrew Quitmeyer100% (3)

- WaterspaceДокумент43 страницыWaterspaceAndrew Quitmeyer100% (1)

- Design Fiction Spring 2017Документ82 страницыDesign Fiction Spring 2017Andrew QuitmeyerОценок пока нет

- MLA Critical Making Quitmeyer Digital Naturalism Living LightningДокумент4 страницыMLA Critical Making Quitmeyer Digital Naturalism Living LightningAndrew QuitmeyerОценок пока нет

- Hacking The Wild Making Sense of Nature in The Madagascar JungleДокумент120 страницHacking The Wild Making Sense of Nature in The Madagascar JungleAndrew Quitmeyer100% (1)

- The Effectiveness of Dyadic Essay Technique in Teaching Writing Viewed From Students' CreativityДокумент145 страницThe Effectiveness of Dyadic Essay Technique in Teaching Writing Viewed From Students' CreativityYunita AngeliaОценок пока нет

- Lesson 1 StsДокумент1 страницаLesson 1 Stsbalisikaisha22Оценок пока нет

- Eternity and ContradictionДокумент111 страницEternity and ContradictionMarco CavaioniОценок пока нет

- Journal 2 PDFДокумент14 страницJournal 2 PDFJayОценок пока нет

- Needs Analysis: Improve This Article Adding Citations To Reliable SourcesДокумент2 страницыNeeds Analysis: Improve This Article Adding Citations To Reliable SourcesMadeleiGOOGYXОценок пока нет

- Intoduction To PhilosophyДокумент10 страницIntoduction To PhilosophyJiffin Sebastin100% (1)

- Intro To Science Notes Including Scientific MethodДокумент33 страницыIntro To Science Notes Including Scientific Methodapi-236331206Оценок пока нет

- Short Truth Table Method Steps Easiest CaseДокумент4 страницыShort Truth Table Method Steps Easiest CaseKye GarciaОценок пока нет

- Intelligence in PsychologyДокумент29 страницIntelligence in PsychologymatrixtrinityОценок пока нет

- Being There Douglas HollanДокумент15 страницBeing There Douglas Hollanweny_lОценок пока нет

- Healing The Angry BrainДокумент1 страницаHealing The Angry BrainMari AssisОценок пока нет

- Chapter Five Research Design and Methodology 5.1. IntroductionДокумент41 страницаChapter Five Research Design and Methodology 5.1. IntroductionFred The FishОценок пока нет

- Learner Autonomy and Self Assessment GuidelinesДокумент2 страницыLearner Autonomy and Self Assessment GuidelinesWillyОценок пока нет

- IT6398 IT Capstone Project 1 PQ1-PQ2Документ9 страницIT6398 IT Capstone Project 1 PQ1-PQ2Melina JaminОценок пока нет

- Work Motivation: Theory and PracticeДокумент10 страницWork Motivation: Theory and PracticeZach YolkОценок пока нет

- ExamДокумент11 страницExamMahendra Singh Meena50% (2)

- G 010 - JOEFEL - Factors Affecting Underachievement in Mathematics - ReadДокумент8 страницG 010 - JOEFEL - Factors Affecting Underachievement in Mathematics - ReadsumairaОценок пока нет

- NCSSM Diagnostic RubricДокумент2 страницыNCSSM Diagnostic RubricCharles ZhaoОценок пока нет

- Abu Saleh Muhammad Saimon - 1510676030 - Section07 PDFДокумент18 страницAbu Saleh Muhammad Saimon - 1510676030 - Section07 PDFAbuSalehMuhammadSaimonОценок пока нет